Abstract

In a series of recent papers, Corine Besson argues that dispositionalist accounts of logical knowledge conflict with ordinary reasoning. She cites cases in which, rather than applying a logical principle to deduce certain implications of our antecedent beliefs, we revise some of those beliefs in the light of their unpalatable consequences. She argues that such instances of, in Gilbert Harman’s phrase, ‘reasoned change in view’ cannot be accommodated by the dispositionalist approach, and that we would do well to conceive of logical knowledge as a species of propositional knowledge instead. In this paper, we propose a dispositional account that is more general than the one Besson considers, viz. one that does not merely apply to beliefs, and claim that dispositionalists have the resources to account for reasoned change in view. We then raise what we take to be more serious challenges for the dispositionalist view, and sketch some lines of response dispositionalists might offer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For simplicity we will adopt MP as our stock example of a piece of logical knowledge. As we will see later, however, it will at times be necessary to consider other types of logical principles. For now we may leave it open how much logical knowledge can be ascribed to the average reasoner.

To be sure, there are a number of responses propositionalists might try to offer in response to each of these objections. Our objective here is not to make the case against propositionalism, but merely to present some prima facie motivations that have led some philosophers to seek alternatives.

A natural reaction to this charge would be to hold instead that propositional knowledge can be a form of implicit knowledge, which can nevertheless become explicit through reflection or theorizing. Similar claims have famously been made by Noam Chomsky with respect to the grammatical competence of ordinary speakers (Chomsky 1986). Other philosophers have questioned the intelligibility of such a notion of propositional but implicit knowledge. Again: here is not the place to address this thorny question.

Cf. Boghossian (2001, p. 638).

Corine Besson’s (expressly provisional) formulation of the proposition supposedly mastered by MP-knowers is a case in point: `P and \(\ulcorner\)if P, then \(Q\urcorner\) implies Q′ (see Besson 2012, p. 20). Besson argues that the conceptual demands that propositionalism places on the average logically competent reasoner are not as stringent as the dispositionalist makes them out to be (idem, p. 78–9).

See Boghossian (2001, p. 26 and ff.).

For Boghossian the aforementioned questions concerning the justification of our logical knowledge and its nature (whether it is a type of propositional or dispositional knowledge) are inextricably linked to the question of our understanding of logical concepts or expressions. For present purposes, however, we do well to distinguish the three questions.

See Besson (2012), passim.

(Crude) is identical to Besson’s principle (DTI) (p. 63).

We follow Besson’s apt terminology here.

Note that this formulation is compatible with views that favor sub-consistency norms of coherence (probabilistic or qualitative), as well as with positions such as Niko Kolodny’s according to which coherence norms are but epiphenomena of more fundamental evidentialist norms of belief (Kolodny 2007).

Let it be emphasized once more that Besson’s argument that we are reproducing here applies across the board to any of the aforementioned exception-tolerating notions of dispositions (masks, antidotes, habituals).

In Besson’s words (Ibid.):

[I]f you really always infer Q once you believe that P and that \(\ulcorner{\hbox { if } P \,\hbox{then}\,Q\urcorner}\), that means that sometimes you will form the belief that Q for an extremely short time—perhaps a nanosecond. But that might not be enough time to form a belief or a proper propositional attitude. (Ibid.)

Besson mentions a fifth objection, viz. that there may be intervening practical reasons.

[S]ometimes you might do nothing whatsoever once you believe P and \(\ulcorner{\hbox { if } P \,\hbox {then}\, Q\urcorner :}\): you might leave the matter there, get distracted or interrupted, or do something completely unrelated. (Ibid). See also Harman (2002).

However, this objection only afflicts crude dispositional accounts.

We should stress that, if dispositionalism is to provide an account of our actual logical knowledge, the following is merely an empirical hypothesis, which would require further support from a fully worked out dispositionalist epistemology. Yet, the hypothesis seems plausible to us: logic students who are taught natural deduction typically eventually develop an ability to use shortcuts in derivations. To be sure, this alone doesn’t show that ordinary speakers learn to use shortcuts. But, it does constitute a reasonable conjecture.

Although dispositionalists typically equate understanding of ‘$’ with a mastery of its introduction and elimination rules (see e.g. Boghossian 2000, 2003), understanding need not be so conceived. All that is presupposed by the argument below is that there be some distinction between basic and derived rules, and that mastering $’s basic rules is sufficient for understanding ‘$’. For expositional convenience we will continue to assume that understanding for logical constants amounts to mastery of the corresponding introduction and elimination rules.

At least this is the case for the dispositionalist accounts of logical knowledge and the understanding of the logical constants discussed so far. The same is not strictly speaking true for the account we present in the next section. As will become obvious, though, the distinctions between basic and derived rules and basic and more-than-basic understanding extends to our account in a straightforward way.

For instance, logically proficient agents will typically master Disjunctive Syllogism, which is, however, a derived rule at least in standard natural deduction systems.

Cf. Christensen (2004, p. 5). Perhaps there is a more sophisticated diachronic normative connection linking logical laws and ordinary reasoning, but like Besson (p. 60), we do not wish to pronounce on this issue here. For recent explorations of some of the more sophisticated accounts of logical laws as diachronic norms of rationality see MacFarlane (2004), Field (2009), Milne (2009), Author (MS).

At least the dispositionalist need not assume that logic plays a grander role in reasoning.

Some authors will protest that even this modest task is more than logic can handle. Pointing to epistemic paradoxes like the lottery and especially the preface paradox, they argue that rational agents may have logically inconsistent beliefs, and that therefore a weaker coherence norm for beliefs is needed (see e.g. Christensen 2004; Easwaran and Fitelson 2012). The issue cannot be adequately addressed in the confines of this footnote. Suffice it to say that even advocates of sub-consistency coherence norms agree that the demand for logical consistency is legitimate when it comes to belief sets of manageable sizes. The modest conception of logic’s role in regulating reasoning need not presuppose anything more than the local applicability of logic-induced synchronic norms of reasoning.

Besson herself mentions this lacuna in the dispositions literature (p. 64). Unlike the standard strictly belief-based dispositionalist approaches, her criticisms apply rather more broadly to any kind of pro-attitude. Nevertheless, as we will see, they do not impact our account, which does not presuppose the formation of anything like a pro-attitude.

An agent may have a wide variety of attitudes vis-à-vis the assumptions made in the course of suppositional reasoning: she may be uncertain about their truth (e.g. to assess their credibility via their consequences or in the case of contingency planning), she may be convinced of their falsity or even know them to be necessarily false (e.g. in the case of an argument by reductio). Suppositional reasoning can thus occur in a host of different contexts: e.g. in thought experiments in inquisitive or theoretical contexts, planning (‘Suppose the mammoth tries to escape to the river …’), arguments or proofs by reductio ad absurdum, conditional proof, heuristic reasoning for purposes of persuasion or for developing an argument (‘Suppose the Archduke Ferdinand had not been assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in 1914, nationalist in 1914, …’), make-belief, fictional contexts, etc.

It seems to us that common philosophical practice, if there is such a thing, would include such acts under the label of ‘inferences’. See for example (Wright 2012). Even so, it will be useful to use a different label to highlight the properties of the mental act we are after.

The perhaps more natural label ‘deductions’ would have precluded applying the dispositionalist framework to non-deductive reasoning, which is something we wish to leave open in this paper.

The label ‘mental act’ is to be understood here so as to make room for the possibility of unconscious ‘acts’ of inferring or transitioning.

Mitchell Green emphasizes this point in his Green (2000, p. 377).

Entertaining and supposing seems to cover just what acceptance covers in Stalnaker (1984). However, ‘acceptance’ is overused enough as it is.

This proviso is important to forestall Harmanian worries of ‘clutter avoidance’. Finite beings cannot possibly attend to all of the consequences of any possible transition. Hence, it is only insofar as the transition is relevant to the agent’s aims and doxastic duties (whether or not the agent recognizes it to be) that she ought to consider its conclusions.

A full account of inference and transition, would have to offer a detailed analysis of the phrase ‘on the strength of’. What is clear is that it must be a specific kind of causal relation, linking the premises to the conclusion of the inference. For discussion about the nature of this causal relation see Boghossian (2012) and the comments by Broome (2012) and (Wright 2012).

Besson discusses a similar objection (p. 75).

We thank an anonymous referee for raising this potential concern.

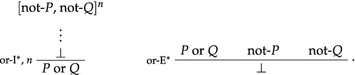

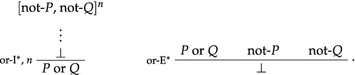

This said, we’d like to suggest that two considerations go some way towards, if not to providing a solution to the problem of alternatives, at least to alleviating some of the burden. The first is that, although training alone cannot account for logical knowledge, it seems plausible to assume that speakers will be more likely to activate dispositions to transition according to the rules that are most often used by their fellow speakers. In conjunction with our earlier observation that, in any given context, speakers will be largely disposed to transition to propositions that are relevant to the topic at hand, this severely constrains the number of propositions that, in a given context, are live options for transitioning in the first place. Secondly, it is worth noting that the problem raised by rules such as (standard) or-introduction depends on the extra assumption that (standard) or-introduction is indeed a basic rule for ‘or’, mastery of which is a necessary condition for having a basic understanding of ‘or’. This assumption, however, can be challenged. One often hears that the standard introduction rules for disjunction do not actually represent the way disjunctions are asserted in everyday practice, and that the meaning of ‘or’ in ordinary language is radically different from its meaning in logic. This complaint seems reasonable enough: we almost always assert \(\ulcorner{P \hbox { or } Q\urcorner}\) on the grounds that P and Q cannot both be false—not because we already know that one of the disjuncts to be true (see e.g. Soames 2003, p. 207). This suggests that inferentialists may substitute the standard rules for disjunction with the following pair of introduction and elimination rules:

Given classical reductio, or-I* and or-E* are provably equivalent to the standard disjunction rules. If mastery of these rules is a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for having a basic understanding of ‘or’, the problem mentioned one paragraph back doesn’t obviously arise.

References

Author. (MS). Author’s publication.

Besson, C. (2010a). Propositions, dispositions and logical knowledge. In L. Angela & B. Maddalena (Eds.), Quid est Veritas? Essays in honour of Jonathan Barnes (pp. 233–268). Napoli: Bibliopolis.

Besson, C. (2010b). Understanding the logical constance and dispositions. In B. Armour-Garb et al. (Eds.), The Baltic international yearbook of cognition, logic and communication (Vol. 5, pp. 1–24). Manhattan, KS: New Prairie Press.

Besson, C. (2012). Logical knowledge and ordinary reasoning. Philosophical Studies, 158, 59–82.

Boghossian, P. (2000). Knowledge of logic. In P. Boghossian & C. Peacocke (Eds.), New essays on the a priori (pp. 229–254). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boghossian, P. (2001). How are objective epistemic reasons possible? Philosophical Studies, 106, 1–40.

Boghossian, P. (2003). Blind reasoning. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 77(1), 225–248.

Boghossian, P. (2012). What is inference? Philosophical Studies. doi:10.1007/s11098-012-9903-x.

Broome, J. (2012). Comments on Boghossian. Philosophical Studies. doi:10.1007/s11098-012-9894-7.

Chomsky, N. (1986). Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin, and use. New York: Praeger.

Christensen, D. (2004). Putting logic in its place. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Easwaran, K., & Fitelson, B. (2012). Accuracy, coherence, and evidence. Unpublished.

Fara, M. (2009). Dispositions. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, summer 2009 edn.

Field, H. (2009). What is the normative role of logic? Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 83, 251–268.

Gordon, R. (1986). Folk psychology as simulation. Mind and Language, 1, 158–171.

Green, M. (2000). The status of supposition. Noûs, 34(3), 376–399.

Harman, G. (1986). Change in view: Principles of reasoning. Cambridge: MIT Press/Bradford Books.

Harman, G. (2002). The logic of ordinary language. In R. Elio (Ed.), Common sense, reasoning, and rationality (pp. 93–103). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heal, J. (1986). Replication and functionalism. In J. Butterfield (Ed.), Language, mind, and logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kolodny, N. (2007). How does coherence matter? Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 107(3), 229–263.

MacFarlane, J. (2004). In what sense (if any) is logic normative for thought? Unpublished manuscript.

Milne, P. (2009). What is the normative role of logic? Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 83, 269–298.

Soames, S. (2003). Philosophical analysis in the twentieth century: The age of meaning. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1984). Inquiry. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Wright, C. (2012). Comment on Paul Boghossian, “The nature of inference”. Philosophical Studies. doi:10.1007/s11098-012-9892-9.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ole Hjortland, Hannes Leitgeb, Catarina Dutilh Novaes and the participants of the first Bristol-Munich Workshop for helpful comments and discussion, and Corine Besson for detailed comments on a previous draft of this paper which led to significant improvements. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Alexander von Humboldt foundation for generous financial support. Julien Murzi further thanks the School of European Culture and Language at the University of Kent and the University of Padua for financial support. The authors are listed in alphabetical order.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murzi, J., Steinberger, F. Is logical knowledge dispositional?. Philos Stud 166 (Suppl 1), 165–183 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-012-0063-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-012-0063-9