Article contents

The Manuscript Tradition of Seneca's Tragedies

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The groundwork for a reliable edition of Seneca's tragedies was done fifty years ago by three men who died in the First World War: C. E. Stuart, T. Düring and W. Hoffa. Yet no complete edition since has taken full account of their work. It is even now not widely enough known that the papers of all three are readily available; Stuart's papers (dissertation, handwritten notes, and collations) are now in Trinity College Library, Cambridge,2 and those of Hoffa and Düring (including a draft apparatus to all the tragedies except Oedipus and most of Phaedra) are in Göttingen University Library.3 Stuart's work has lain in particular obscurity, and for my work on the tradition I have given especial attention to it.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1968

References

page 150 note 1 I am grateful to Dr. A. H. McDonald and Miss A. Duke for reading a draft of this article, and for their suggestions; also to Mr. E. J. Kenney for some criticisms.

The following works are cited by short titles:

Brugnoli—Brugnoli, G., La tradizione manoscritta di Sesneca tragico alla lute delle testimonianze medioevali (Mem. Acc. Naz. dei Lincei. Ser. 8, vol. viii [Rome, 1959], pp. 201–87).Google Scholar

Düring (1907)—Düring, Th., ‘Die Überlieferung des interpolierten Textes von Senecas Tragödien’, Hermes xlii (1907), 113–26 and 579–94.Google Scholar

Düring (1912)—Düring, Th., ‘Zur Überlieferung von Senecas Tragödien’, Hermes xlvii (1912), 183–98.Google Scholar

Düring (Ergänzung)—Düring, Th., Zur Uberlieferung von Senecas Tragodien. Erganzung zu den Abhandlungen im Hermes xlii (1907) und xlvii (1912). I. 37 Handschriften in England. 2. T und C (Lingen, 1913).Google Scholar

Herington—Herington, C. J., ‘A thirteenth-century manuscript of the Octavia Praetexta in Exeter’, Rh. Mus. ci (1958), 353–77.Google ScholarCorrections in Rh. Mus. ciii (1960), 96.Google Scholar

Hoffa—Hoffa, W., ‘Textkritische Untersuchungen zu Senecas Tragödien’, Hermes xlix (1914), 464–75.Google Scholar

Stuart (1911)—Stuart, C. E., ‘The Tragedies of Seneca. Notes and emendations’, C.Q. v (1911), 32–41.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Stuart (1912)—Stuart, C. E., ‘The MSS of the interpolated (A) tradition of the tragedies of Seneca’, C.Q. vi (1912), 1–20.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Ussani—Ussani, V., Jr., Per it testo delle tragedie di Seneca (Mem. Acc. Naz. dei Lincei. Ser. 8, vol. viii, (Rome, 1959), pp. 489–552).Google Scholar

Diss. —Philp, R. H., Dissertation, ‘The manuscript tradition of Seneca's Tragedies’ (1964), Camb. U.L. Ph.D. Thesis.Google Scholar

page 150 note 2 Add. MS. b. 67 and Add. MS. d. 63; also two notebooks, Add. MS. b. 57 and Add. MS. C. 79.

page 150 note 3 Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitatsbibliothek, MS. 4° Philol. 142n.

page 150 note 4 By the kindness of the late Prof. D. S. Robertson and of Mr. A. S. F. Gow of Trinity College, I have been able to study the Stuart papers in great detail. M v thanks are also due to Dr. Denecke, of Gottingen, for making the Hoffa-During Materialien readily available.

page 151 note 1 See Billanovich, , I primi umanisti e le tradizione dei classici Latini, ii. 19 ff.Google Scholar He maintains, though without firm evidence, that this was the manuscript seen at Pomposa by Lovato Lovati, and written in 1093.

page 151 note 2 Of 1661; edited cum notis variis aliorum by his son in 1682.

page 151 note 3 Inaccurately; e.g. at Med. 653 he read serpens as sepi.

page 151 note 4 Followed by Peiper and Richter in the first Teubner edition of 1867.

page 151 note 5 See Richter, , De corruptis quibusdam Senecae tragoediarum locis, pp. 5 ff.Google Scholar In collating E for the Medea, I have noted only one or two places where Leo's account of E is wrong or inadequate (581: E has taetlis, not taedis; 775: the letters ec in vectoris are written over an erasure). Later editors sometimes showa deterioration from his account (as Herrmann and Moricca at Med. 631).

page 151 note 6 Available to Richter for the second Teubner edition of 1902. He declares (Praefatio vii f.) that Leo and Ribbeck agree almost everywhere, and only a very few readings were neglected by one or the other.

page 151 note 7 Phaedra ed. (Rome, 1955).Google Scholar He cites its readings continually, even when simply supporting E.

page 151 note 8 Before the discovery of C and P (early to middle thirteenth century), Düring suggested a date for A in thirteenth century. Pasquali, (Storia della tradizione, p. 127)Google Scholar tentatively supports this.

page 151 note 9 According to W. Meyer. See Düring (1912), 187 and 189.

page 152 note 1 Apparatus criticus to all plays except most of the Phaedra and all the Oedipus.

page 152 note 2 See p. 151, n. 9.

page 152 note 3 Part Ia of the Göttingen Materialien has photographs of S.

page 152 note 4 Hoffa dates in the fourteenth, Stuart in the fifteenth century.

page 152 note 5 Beltrami dates in the fifteenth, Stuart inthe second half of the fourteenth century.

page 152 note 6 For Trevet's life and works, see especially Ehrle, F., Nikolaus Trevet, sein Leben, seine Quodlibet and Quaestiones ordinariae (Münster, 1923)Google Scholar, Franceschini, Studi e note and II Commento di Nic. Trev. al Tieste di Sen. ed., Introd., and review by Dean, Ruth J. (Medium Aevum x [1941], 161–8).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 153 note 1 Dated by M. R. James to the thirteenth, by Stuart to the beginning of the fourteenth century.

page 153 note 2 Read as 1385 by Stuart.

page 153 note 3 The fragments are very hard to read (see specimen in Lowe, E. A., Codices Latini Antiquiores [Oxford, 1938], iii, No. 346, p. 24)Google Scholar, and their collation blinded Studemund. He marks the places where there is doubt, and his is generally accepted as a reliable account —though I have noted five places where Leo himself seems in his apparatus to differ from Studemund (Med. 201, 273, 721, 740, Oed. 536) and ten where Herrmann does.

page 153 note 4 For comparative lists of readings, and arguments against Studemund's view that it was basically of the E tradition. See also Stuart (Dissertation, 19 ff.).

page 153 note 5 The deeply corrupt excerpts in the Thuanean codex (T) are of the E branch. MNF are much later (fourteenth century), heavily interpolated from A, and, as Leo held (edn., Obs. Crit., pp. 7–15), probable descendants of E itself.

page 154 note 1 Whether the AE manuscripts give us evidence which is not in the Etruscus itself is considered below.

page 154 note 2 See their 2nd Teubner edition of 1902, and Richter, G., De corruptis quibusdam Senecae tragoediarurn locis, 1894Google Scholar, and Kritische Untersuchungen zu Senecas Tragödien, 1899.Google Scholar

page 154 note 3 Stuart (1912, p. 1) gives a full list.

page 155 note 1 As Hoffa pointed out in a letter to Daring (Göttingen Materialien, Part 3).

page 155 note 2 They were already providing exempla for moralists and preachers. See Franceschini, E., Studi a note di filologia latina medioevale, 1938, 7–8.Google Scholar

page 155 note 3 ‘Studia critica in Senecae Phaedram de codicibus interpolatis P et C’, Mnemosyne iv.1 (1948), 139–60.Google Scholar

page 155 note 4 In a manuscript note prefacing the textual apparatus in the Göttingen Materialien (Part IVa).

page 155 note 5 Before the discovery of C and P. It should now perhaps be dated in the late twelfth century.

page 156 note 1 In A the Medea ended with Jason's remark unus est poenae satis. Only one of his children has been killed and Medea's escape has not yet been effected. An imaginable ending in a modern version, but barely a dénouement for the ancients.

page 156 note 2 Düring explained the presence of 1010–11 in n and some other manuscripts by suggesting that A was mutilated here in such a way that some scribes could read more than others. This is unlikely when two extra lines are involved, and above all when the last line of the play, 1027, is also present; its inclusion confirms contamination.

page 156 note 3 In Stuart's view. But the branch is also represented in G for the Octavia. Traces may also lurk in L and Exc. B.

page 156 note 4 1912, p. 19.

page 156 note 5 p. 373.

page 156 note 6 p. 371.

page 156 note 7 See p. 371.

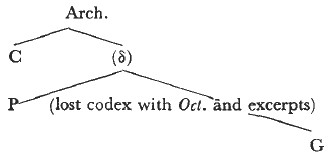

page 157 note 1 Herington's stemma (p. 356) is this:

This fails to explain why G's text of the excerpts is far less accurate than its text of the Octavia.

page 157 note 2 To conclude, as I do below, that the florilegia are independent of the hyparchetype of CS recc. is natural in view of their early date and does not justify associating P with their deficiencies.

page 157 note 3 pp. 373–4.

page 157 note 4 p. 373.

page 157 note 5 G incidentally supports C in agreements with E against P six times. But the fact that P was little, if at all, copied, and so has many more unique variants, leads Herington to think of it in an entirely different light from C.

page 157 note 6 This corruption may have been of any sort, and could have caused substantial changes in a single copying. This can, for instance, happen by confusion of abbreviations, as at Oct. 489 (see below).

page 158 note 1 It must be concluded from these two places that emendation occurs even between A and β. Further examples of P's value in the Octavia are fairly frequent, e.g. 495 (cives P recc.: vices Cl1 Ag.: viros n12) and 882 (Gracchos: graccos P: gracos G: gratos C:gratos vel gnatos A (Moricca)).

page 158 note 2 Referred to as AL, AR, AM, and AH. This procedure is followed by Sluiter in his examination of the evidence of CPS in the Phaedra (Mnemosyne iv. I (1948), pp. 139–60).Google Scholar

page 158 note 3 For a fuller account, see Diss. 43–50.

page 159 note 1 Unique among A manuscripts, that is. In the two places quoted, the early Ambrosian fragments come into the reckoning.

page 159 note 2 Taken separately, they show one or two small superiorities to the other A manuscripts: 20 (![]() EC erret PS recc.), 28 (hoc ES haec PC nrd), 312 (poterat ES: poterant PC recc.).

EC erret PS recc.), 28 (hoc ES haec PC nrd), 312 (poterat ES: poterant PC recc.).

page 159 note 3 Being unable to examine C and P. He also used the already known sources Ag. and τ.

page 159 note 4 Düring, however, commented in a note prefacing the apparatus, ‘Mit Absicht habe ich n b (= I) r höchst selten einzeln ausgeführt. Sie können in der Tat entbehrt werden.’

page 160 note 1 See below (iii) for m, p, and q. Hoffa (1914) also noticed m and p and classed them with lnr in a group γ, but followed During in remarking that γ could be well enough known from lnr, so that m and p are superfluous.

page 160 note 2 What follows is a summary of d's witness in the Medea. For detailed statistics, see Diss. 57–67.

page 160 note 3 Düring supposed that A was mutilated at the end of the Medea in such a way that some scribes could read more than others. This would not account for the presence of 1027 in n, and it probably drew 1009–10 from the same source as that line. Scribes finish either with 1008 or 1010; but it is unlikely that if the text were mutilated some could read two more lines than others. CPS all end at 1008, and the introduction of 1009–10 (and 1027) is best conceived as an attempt to remedy an unbearably inconclusive ending at 1008 ( JAS. Unus est poenae satis).

page 160 note 4 My account of CPS and d in the ensuing statistics is drawn from my own collations. My account of Inr is taken from Hoffa and Düring's draft apparatus (which reports them fully), supported by Moricca's account of A.

page 161 note 1 Of these manuscripts, though it survives elsewhere in m.

page 162 note 1 He commends the account of manuscript relations by Düring (1912), 192, who gives this stemma for ln.

page 164 note 1 In one or two places these may have been readings offered as variants in A itself, and genuinely primitive. See, e.g., Med. 377, 457, 625, 655, where C gives a marginal variant and both readings appear in recc.

page 164 note 2 Those where there is disagreement between primitive A manuscripts.

page 164 note 3 But this is written over an erasure.

page 164 note 4 cui feminea nequitia ECPSdmr: neq. cui fern. In.

page 164 note 5 Stuart described it in his notes as ‘a good, perfectly pure version of my best type’; but ‘not quite of highest class’.

page 164 note 6 Their stemma is complex. See Franceschini, op. cit., Fabris, V. (Aevum, 1953, 498–509)Google Scholar, and cf. Ussani's edition of the commentary to H.F. (Rome, 1959)Google Scholar, vol. ii Introd., x-xxvi, and Meloni's of the Agamemnon (Cagliari [Palumbo], 1961).Google Scholar Franceschini thought T, V, and, to a lesser degree, P the best manuscripts of the commentary, but Ussani, supported in substance by Meloni, corrects his stemma and posits eight independent witnesses.

page 164 note 7 He used a single manuscript. De textu, quem unicum habui, qualemcumque sensuum explanationenz exculpsi he wrote to Cardinal Niccolo Alberti da Prato.

page 165 note 1 Göttingen Materialien, Part III.

page 165 note 2 p. 527.

page 165 note 3 p. 545.

page 165 note 4 labor and opus are quoted from Trevet's letter to da Prato.

page 165 note 5 These, owed to Herrmann, Ussani, and Courtney, are extra to Stuart's list and that of Ussani (p. 520), which contain between them the clearest examples but which I do not duplicate here.

page 166 note 1 Düring was misled by his MS. of the commentary over τ's reading here. Nearly all the other manuscripts support Stuart's Soc.

page 166 note 2 These are cited by Düring and Ussani (who does not cite S, but gives the account of ‘A’ in the editions of Richter, Herrmann, and Moricca) in arguing for the value of τ.

page 166 note 3 Rehdigeranus 14, Düring's Trevet manuscript, gives, at Tro. 488, misera tremisco omen feralis loci and, at Oed. 69, levat pro allevat. Possibly his manuscript with others interpolated here; but such interpolation is far less likely in a commentary than a text.

page 166 note 4 Göttingen Malerialien, Part III.

page 167 note 1 In the Thyestes (chosen quite at random), he cites τ six times in the first 200 lines.

page 167 note 2 p. 502.

page 167 note 3 See list of examples of τ following C.

page 167 note 4 The same is true of its attendant family, for instance the text of Soc. (cf. Stuart (1912), 13 ff.) and Bodleian, d'Orville 176 (Auct. x. I. 5. 29).

page 167 note 5 Twenty-one from my own examinations, the rest gleaned from Stuart's hand-written notes. Only a fraction are referred to at each place, but this is due both to (i) the necessary sparseness of Stuart's notes, and (ii) the fact that no AE manuscript fills all the A lacunae.

page 167 note 6 Apart from LH Eton. B, only the number of manuscripts is referred to. The first reading given at each line is the correct one, except where indicated.

page 168 note 1 This text is not certainly right, but I agree with Carlsson, (Zu Senecas Tragödien, [Lund, 1929], p. 10)Google Scholar that a genitive is needed; this reading, if correct, would easily explain the corruptions of E and of LH, etc.

page 168 note 2 E's summa, with Oeta in the same line, is probably right, but the accusative present in summum, which nearly all manuscripts combine with some form of Oetam, here has claim to consideration.

page 168 note 3 I do not include suppliciis in EL at 1015, where editors generally write supplicis, and L's natos at 1024 for the editors' gnatos.

page 168 note 4 MNF are probably offshoots of E, and influenced by A. The Thuanean excerpts, of the E tradition, are sparse and inaccurate.

page 168 note 5 The question is naturally whether their non-A readings originated in the Etruscus. E was directly used by virtually no extant AE manuscript. See, e.g., H.F. 20 (nuribus sparsa tellus 14 (recte): tellus nuribus sparsa E+ 1), Oed. 433 (Eden ope depulsavit E: 24 alii aliter, ex quibus duo recte), 442 (oestro remissae E+ I: ostro remissa 14), H.O. 48 (in me incucurrit E + 1: in me cucurrit 10: in me incurrit 9: in me currit 2) and H.F. 133, Oed. 470, Med. 1026, noted above.

page 168 note 6 In his dissertation, p. 189 (Trinity College Library, Cambridge. Add. MS. b. 63 and 67).

page 168 note 7 With the exception of G in the Octavia, and perhaps some of the excerpts (see below).

page 168 note 8 Düring lists most of these (1912), 189, n. 2.

page 169 note 1 As some of those cited by Düring in his indictment of L (1907), 122–5.

page 169 note 2 Stuart: ‘The first half of the fourteenth century.’

page 169 note 3 Also of this group are Vatican, lat. 1647 (1391) and Cambridge, Univ. Lib. Nn. II. 35 (fifteenth century).

page 169 note 4 By the kindness of Dr. G. C. Giardina of Bologna University.

page 169 note 5 Though P may have miseriis.

page 169 note 6 See Courtney, review of Ussani's edition of Trevet's commentary on the H.F., C.R. N.S. xi (1961), 166 f.Google Scholar

page 169 note 7 Especially in view of their willingness to conjecture.

page 169 note 8 For the principle, see Pasquali, , Storia della tradizione e critica del testo, Pref., xvii.Google Scholar

page 169 note 9 Their quality demands further assessment, but I provisionally direct attention to LH Eton. B, as above.

page 169 note 10 p. 156.

page 170 note 1 1912, p. 7 n.

page 170 note 2 p. 466.

page 170 note 3 p. 466.

page 170 note 4 pp. 277–80.

page 170 note 5 Since he believes that the tradition did not divide until after the date of T, the ‘A-revision’ had in his view not yet occurred. These medieval witnesses, he points out, often support and thus show the value of A, when its obvious interpolations are discounted. See below pp. 175 ff.

page 170 note 6 He seems to rely on the apparatus of Moricca's edition, which a comparison with Sluiter's excellent apparatus to the Oedipus reveals as inadequate and unsound.

page 171 note 1 Thus Sluiter, (Mnemosyne iv. 1 [1948], 147)Google Scholar could remark of In, which Stuart knew well, ‘Stuartius hos codices inspexisse non videtur’.

page 171 note 2 While only able to look at a few passages in each, he chose those where their text gives clear evidence of their affiliations. Somewhat likewise Snell, (Philologus xcvi [1944], 160)Google Scholar points out Phaedra 1030 as a proof passage.

page 171 note 3 308 are listed in the Index of manuscripts known to him in the Hoffa-Düring Materialien (II. 1–18).

page 171 note 4 See above, pp. 163 f. Also, some recentiores are probably descended from each of CS, which the stemma does not show.

page 172 note 1 Herington, p. 372.

page 172 note 2 Oedipus ed. (Groningen, 1941).Google Scholar

page 172 note 3 In a manuscript note to the apparatus in the Göttingen Materialien (Part IVa).

page 172 note 4 See below IV (iii). This does not mean that the evidence of the florilegia and the LH group is to be jettisoned; they are rather to be mentioned separately, if ever of interest.

page 172 note 5 Göttingen Materialien, manuscript note prefacing apparatus in Part IVa.

page 172 note 6 Die Überlieferung der Sen.-Trag. Stuart's treatment in his dissertation is in some respects much more detailed.

page 173 note 1 See Pasquali, , Scoria della tradizione e critica del testo, pp. 126 ff.Google Scholar

page 173 note 2 And often elsewhere.

page 173 note 3 Though his evidence for the Thuanean excerpts is faulty. His interpretation of this medieval evidence is quite different, since he believed that the tradition did not divide until after these quotations. See below.

page 174 note 1 Dissertation, The Tragedies of Seneca, pp. 19 ff.

page 174 note 2 The lightly contaminated recentiores called A by previous editors would show some agreements with E which were not in A.

page 174 note 3 Stuart's example. P has durescunt which is ‘difficilior’ and must have been in A. It is far from a certain reading, but cf. aqua dura in Celsus 2, 30 fin.

page 174 note 4 Carlsson's example. CPS have gloriae. The source of Graeciae in the recentiores is an intriguing question.

page 174 note 5 Not a certain example, but Graeciae is in most editions. At Med. 267 too (feminae R: feminea ECPS) R is probably right.

page 174 note 6 In each place R is wrong. Insignificant variations, typical of contemporary spelling, are omitted.

page 175 note 1 P's omission seems an individual error.

page 175 note 2 A is also approved by some editors against RE at Oed. 404 (armatus RTE: armati A). But this may be a conjecture, and the verse has been variously emended. See Sluiter, , Oedipus. Obs. Crit., pp. 94 f.Google Scholar

page 175 note 3 The tiny variation at Med. 218 (tunc E: tum RA) is barely significant.

page 175 note 4 In R, according to Studemund. The place is now virtually unreadable.

page 175 note 5 The text of A is not quite certain, as P appears to have miseriis; this word is all that is definite in a vexed place. The full position is terrain miseriis E: terram ac miseris RA.

page 175 note 6 References in all recent editions. The earliest quotation, by Augustine, is probably of 400.

page 175 note 7 At one or two places they support E against a small mistake in A, as at Phaed. 195 (turpis et vitio E: turpi servitio A).

page 175 note 8 Though the Halberstadt and Karlsruhe manuscripts of Priscian have facias.

page 175 note 9 Only Phaed. 710 is quite definite, but Phaed. 195 is virtually so; remarkably, editors as recent as Moricca read furens with E, removing the whole point of the verse.

page 175 note 10 Above all it does not show that the tradition had already divided at the time of the quotations, if at these places A simply reproduces the archetype. Stuart points out this error of Richter, (Kritische Untersuchungen [1899], p. 6Google Scholar: ‘Die erste Spur dieser Rezension (i.e. A) begegnet bei Augustinus... Dann bei Ennodius... (etc.)... Demnach darf die Entstehung der interpolierten Ausgabe in kein späteres als das 4. Jahrhundert versetzt werden’).

page 175 note 11 With the exception of T, where Brugnoli's evidence and conclusion are at fault. See above, pp. 170 f.

page 177 note 1 Only a selection follows. Stuart has a fuller list (Dissertation, The Tragedies of Seneca, pp. 28 f.), and many of these examples are his.

page 177 note 2 Stuart explains this frequent confusion as most likely in a majuscule manuscript of the type of the Medicean Virgil (cf. reproduction, Palaeological Society, vol. i, pl. 86), exhibiting a kind of careless writing which does not seem to have continued beyond the sixth century.

page 177 note 3 Though individual readings of E were known widely by collation.

page 177 note 4 The text of R shows remarkably few superiorities to E in spite of being six or seven centuries older.

page 177 note 5 c and t are confused at H.F. 1078 and 1278. Stuart lists a number of these examples. See also Brugnoli, pp. 281 f.

page 178 note 1 Especially since R is so hard to read, and Studemund, in finding caput here, was certain only of the letters CAP.

page 178 note 2 If R is right at Med. 267, the same may be said as of 220.

page 179 note 1 The systematic revision which changed the order and titles of the plays, incorporated the Octavia, and doctored the style of the text. This is not to say there were not other interpolators at different periods.

page 179 note 2 Edn. vol. i, p. 4. ne in eis quidem quae corrupte Etruscus praebet ullam esse vulgaris lectionis auctoritatem.

- 4

- Cited by