Abstract

It is commonly thought that mental disorder is a valid concept only in so far as it is an extension of or continuous with the concept of physical disorder. A valid extension has to meet two criteria: determination and coherence. Essentialists meet these criteria through necessary and sufficient conditions for being a disorder. Two Wittgensteinian alternatives to essentialism are considered and assessed against the two criteria. These are the family resemblance approach and the secondary sense approach. Where the focus is solely on the characteristics or attributes of things, both these approaches seem to fail to meet the criteria for valid extension. However, this focus on attributes is mistaken. The criteria for valid extension are met in the case of family resemblance by the pattern of characteristics associated with a concept, and by the limits of intelligibility of applying a concept. Secondary sense, though it may have some claims to be a good account of the relation between physical and mental disorder, cannot claim to meet the two criteria of valid extension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is commonly thought that mental disorder is a valid concept only in so far as it is an extension of or continuous with the concept of physical disorder. This raises the question: does the notion of disorder which applies to, say, cancer, pneumonia, diabetes and other physical disorders, validly extend to schizophrenia, bi-polar affective disorder, anti-social personality disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and other claimed mental disorders? That turns the spotlight on how this question might be answered. What makes an extension such as this valid or invalid?

One response to this question is: conditions such as schizophrenia and the rest validly fall under the concept disorder if—and only if—they have the necessary and sufficient conditions for being a disorder. This will be referred to as the essentialist response.Footnote 1 The essentialist about disorder, to paraphrase Beardsmore (1992, p. 133), looks for the common characteristic or characteristics of all and only disorders. In Pitcher’s (1964, p. 217) phrase, essentialists are characterised by their craving for unity.

In this paper two alternatives to essentialism are considered: they are both derived from the later writings of Wittgenstein. They suggest ways ‘disorder’ might be extended to cover mental disorders which don’t rest upon necessary and sufficient conditions. They are the family resemblance and secondary sense approaches. The primary point of this paper is to assess whether (and if so in what way) these approaches offer a reasonable basis for determining whether both physical and mental disorder fit under the concept disorder. Do they meet the requirements of extension of a concept; if so, how? Have they any stronger claims than essentialism?

A note on the scope of the paper and the use of the term ‘disorder’

This paper focuses on the extension of the concept of disorder from physical to mental conditions. This has been a concern for a tradition of writers starting at the latest with Szasz (1960). Recent writers have drawn attention to what may be a related debate, about the apparent epidemic of mental disorder sweeping across the USA (Angell 2011a, b; McNally 2011). They wonder how far this is really an epidemic of mental health problems and how far an epidemic of conceptual expansion. A further, parallel issue of extension is whether some physical conditions (such Repetitive Strain Injury, also known as Occupational Overuse Syndrome) are really disorders (Lucire 2003). This paper does not set out to consider these cases, but, in principle, the arguments here could apply to them.

Except where the context demands it, the term ‘disorder’ will be used throughout this paper. Writers who have considered the question whether conditions such as schizophrenia should fall under the same concept as conditions such as pneumonia and cancer use a number of different terms (e.g. disorder (Wakefield 1992a, b, 1999); disease (Boorse 1977, 1982, 1997; Cooper 2002, 2007; Nordenfelt 2007); illness (Fulford 1989); malady (Clouser et al. 1981; Culver and Gert 1982); and sickness (Brody 1985)). These authors assign different meanings to these terms, even where they use the same word (for example, Boorse’s, Cooper’s and Nordenfelt’s definitions of ‘disease’ are quite different). The arguments of this paper are neutral with regards to this variety of conceptualisations, and the term ‘disorder’ will not have any particular conceptual content assigned to it.

Criteria for the valid extension of concepts

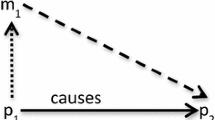

Extending a concept refers to increasing the range of things which can be brought under the concept, or which fall within a category, or to which a kind term can be applied. The increase is from a baseline which is the agreed range of usage, reflecting what Wakefield calls “relatively uncontroversial and widely shared judgements” about what does (and does not) fall under the concept (Wakefield 1992b, p. 233).

Given the presence of such a baseline, one criterion of extension suggests itself immediately. An extension should neither go too far beyond the baseline and include things which should not be included within the concept; nor fail to go far enough beyond it, and exclude things which should be included under the concept. In other words, any proposed basis of extension should avoid what Bellaimy (1990, p. 43) calls the problem of the under-determination of extension. (This is a problem he discusses in connection with family resemblance.) An example of a problem of an under-determined extension arose with the concept ‘planet’ in the early 2000s. Astronomers clearly agreed on the baseline members (e.g. Earth, Mars, Jupiter) and had traditionally extended the group to include Pluto. But in the light of the discovery of Pluto-like objects such as Eris, Makemake and Haumea in the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune, it became unclear whether the concept ‘planet’ should extend to Pluto or not, resulting in a good deal of disagreement amongst astronomers (Hogan 2006; Schilling 1999, 2006; Sheppard 2006). Echoing such concerns Horwitz suggests that to be an “adequate concept of mental illness” a concept must demonstrate the capacity to “distinguish conditions that ought to be called ‘mental illnesses’ from those that ought not” (2002, p. 10). Horwitz has in mind specifically the distinction of mental illnesses from social deviance. In a similar vein, Wakefield says that “a correct understanding of the concept [of disorder] is essential for constructing ‘conceptually valid’ … diagnostic criteria that are good discriminators between disorder and non-disorder” (Wakefield 1992a, pp. 373–374; see also Wakefield 1992b). The criterion of valid extension implied by Bellaimey, Horwitz, and Wakefield will be named the criterion of determination.

But, a criterion of determination may be necessary but is not sufficient as a basis for extension. If determination were the only issue, a concept could be claimed to exist for a random but clearly limited list of items. However, intuitively, random lists of items do not imply the existence of any covering concept. What, for example, is the concept implied by √9, the chair I’m sitting on, Beijing, and the Mona Lisa? What is lacking from this set of items is any sense that they belong together. There is a need for a criterion of coherence. Applied to a list that includes pneumonia, cancer, schizophrenia, and narcissistic personality disorder, the criteria of coherence requires that this is not a randomly assembled list of items.

Essentialism meets both the criteria for valid extension by means of the necessary and sufficient criteria for falling under a concept. These necessary and sufficient criteria are derived from the characteristics of the things which fall within the baseline. The approach ensures those things included seem to belong together because all things that fall under the concept have the same characteristics. A basis for determination is given because a clear set of boundary conditions is described; if something doesn’t meet the necessary conditions for coherence, it is excluded; and if it does, it is included. The essentialist presumes, then, that things fall under a concept because of or in virtue of their characteristics.

Family resemblance

Family resemblance is a non-essentialist account. This is not simply because it rejects the use of necessary and sufficient criteria, but because it raises a question over the relation of the attributes of things to the concept they should fall under.

No one currently and unequivocally deploys the family resemblance approach to analyse the extension of disorder.Footnote 2 The possibility that (in Bengt Brülde’s words) “‘mental disorder’ is a ‘family concept’” (Brülde 2010, p. 31) is quite frequently mentioned (Brody 1985, p. 250; Cooper 2007, pp. 41, 43; Engelhardt 1975, p. 126Footnote 3; Fulford 1989, p. 134; Murphy 2006, p. 22; Reznek 1987, p. 76; Sadegh-Zadeh 2008, p. 118). But of these authors, some reject the analysis, and seek something better; others accept it but see this as a reason to shift to a different approach. Cooper (2007, pp 42, 43) is in the first camp: she suggests we should continue the search for an essentialist analysis rather than accept a “no-account account”. Murphy (2006, p. 22) is in the second camp, and argues that the notion of disease is a “loosely united family of ideas” because it is a folk concept, and so is unsuited to the conceptual analysis of psychiatric disorders. The closest approach to family resemblance which its authors describe and embrace are McNally’s (2011) analysis, which uses the label ‘family resemblance’ but is analysed as a Roschian (prototype resemblance) approach, and Lilienfeld and Marino’s (1995) and Sadegh-Zadeh’s (2008) Roschian analyses.Footnote 4 But as Sadegh-Zadeh argues, Roschian analyses differ from family resemblance approaches in their focus on prototypes or ideal examples. Prototypes have no place in a family resemblance account.Footnote 5

In the family resemblance approach, no one characteristic, or set of characteristics, is necessary in order for something to fall under a concept. Looking over those things called disorders, and at the characteristics they have, one taking the family resemblance approach would be able to adapt Wittgenstein’s oft cited analysis of games. “For if you look at them you will not see something common to all, but similarities, relationships, and whole series of them at that” (Wittgenstein 1992, §66, p. 31e).

This section of the paper looks at a family resemblance account of extension of the ‘disorder’ concept to mental disorders. An apparent problem for the family resemblance approach is that the similarities and relationships associated with a concept are subject to revision. New characteristics, or features or attributesFootnote 6 can be added to the pool of those associated with the concept. This possibility seems to threaten the ability of a family resemblance account to meet the criteria of either determination or coherence. But this problem is more apparent than real. It arises where family resemblance is presumed to rely on the role of shared characteristics or attributes in determining category membership. The family resemblance approach to concepts necessarily and rightly rejects this reliance.

The family resemblance approach can be represented schematically and abstractly, using a symbolism adapted from Bambrough (1970, p. 189). Five things (labelled here A, B, C, D, E) are agreed to fall under a concept—they form the baseline of agreed examples. There are also five characteristics or attributes the things collectively have (labelled I, II, III, IV, V).Footnote 7 Each of the things has four of the characteristics, but each has a slightly different set:

-

A [I, II, III, IV]

-

B [I, II, III, V]

-

C [I, II, IV, V]

-

D [I, III, IV, V]

-

E [II, III, IV, V]

Consistent with the main point Wittgenstein seems to be making, there is nothing these five things all share. But they all draw upon the same pool of characteristics, and each thing shares three characteristics with each of the others.

Now, let it be asked: does a further thing (F) which has the following characteristics, also fall under the concept in question:

-

F [III, IV, V, VI]

This shares at least three characteristics with D and E. If, on these grounds, this is allowed to be a new instance of the concept, a further characteristic (VI) may now be considered a characteristic of things of this kind. And so the characteristics which are associated with the concept are increased in number and range.Footnote 8

These observations fit with Wittgenstein’s own reflections on the family resemblance account where for example he considers the concept of number. He notes that “we extend our concept of number as in spinning a thread we twist fibre on fibre” (Wittgenstein 1992, §67, p. 32e). It might be said that characteristic VI is a new fibre to be twisted into the thread.

Perhaps something similar may be said to happen with disorder, when the question arises whether it extends from the agreed baseline to conditions such as schizophrenia. Suppose that the five things (A–E) are agreed (physical) disorders, and that the attributes represented by I–V are:

- I:

-

a lesion in some bodily organ

- II:

-

diagnosable by physical signs

- III:

-

responds to medical treatments such as drugs

- IV:

-

results in harms, such as pain or fears

- V:

-

is genetically predisposedFootnote 9

Does the concept disorder extend to schizophrenia if it is characterised as F was previously (i.e. as having III, IV, V and an additional characteristic VI)? It may be argued that it does because schizophrenia shares at least three of these characteristics with agreed disorders.Footnote 10 But, many of the individuals who have this condition also have an additional characteristic (VI); this might be having bizarre beliefs—delusions for instance that their lives are the object of a world-wide conspiracy, or that their thoughts are being broadcast.Footnote 11 If schizophrenia is allowed to be a disorder, then delusions will be added to the list of characteristics associated with disorder.

FR and the valid extension of concepts

The mutability of the set of characteristics associated with a concept in the family resemblance approach seems to threaten to undermine both coherence and determination. Consider a pattern of behaviour (G) with the following characteristics.

- VII:

-

a failure to conform to social norms

- VIII:

-

impulsivity and aggressiveness

- IX:

-

deceitfulness

- X:

-

lack of remorse

(These are derived from DSM-IV-TR criteria for Anti-Social Personality Disorder. Despite its name, the medical status of ASPD is contested (van Marle and Eastman 1997; Frances 1980)). As described here, this condition has no overlap with the existing set of characteristics associated with the notion of disorder, and so on a family resemblance account there is no reason to bring this instance under the concept. However, this can change. There is reason to think that there is a subgroup (G*) amongst those exhibiting anti-social personality disorder who also respond to medical treatments (III), are typically harmed (e.g. suffer a sense of social isolation) (IV) and have a genetic predisposition (V) (Moran 1999). If sharing three attributes or features with things which are agreed disorders, is sufficient to make something a disorder, then G* will be a disorder, and since the gap between F (schizophrenia) and G (anti social personality disorder) has now been bridged, it too will be a disorder.

In the light of this, a family resemblance account of disorder does not appear to meet either criterion for extension. The attributes don’t appear to determine any limits to extension, since they seem to be an indeterminately extendable list. Further, A and G are now included, yet they share no attributes, and so it is unclear what the rationale for including both might be. In terms of judgements about what is and what is not a disorder, this appears to have the conceptually disastrous consequence of suggesting that disorder extends even beyond so called anti-social personality disorder to ordinary anti-social behaviours and beyond that to ordinary social behaviours. Using a similar sort of analysis (though with quite different ends in view), Bentall (1992) has suggested that on the basis of other shared characteristics of agreed disorders we should extend the concept disorder to include ordinary human happiness.Footnote 12

But these problems for the family resemblance approach are more apparent than real. They have arisen as a result of focusing on the role of the attributes or characteristics of things in deciding category or kind membership. This focus on the characteristics represents a mistaken approach to family resemblance.Footnote 13 Characteristics in the family resemblance approach to concepts do not have the determinative relation to the concepts with which they are associated that they have in the essentialist approach. Furthermore, this is a strength of the family resemblance approach, for the kind of relationship the essentialist presupposes between characteristics and concepts is far from self evident.

To understand the relationship between the characteristics or attributes of conditions such as pneumonia and schizophrenia and the concept they fall under in the family resemblance approach, the argument so far considered against the family resemblance approach must be turned on its head. The possibility inherent in family resemblance of continuously extending the features associated with a concept indicates the existence of a non-determinative relationship between those features and the concept they are associated with. It is just because networks of resemblances exist between quite different kinds of things that the family resemblance approach necessarily introduces a further factor. In the family resemblance approach it becomes clear that some judgement has to be made about whether shared attributes do or do not count towards various human patterns of behaviour and experience being disorders. Should similarities between anti-social personality disorder and other agreed or claimed disorders count towards a judgement that anti-social personality disorder is also a disorder? Should similarities between anti-social personality disorder and ordinary anti-social behaviour count or not-count towards a judgement that ordinary anti-social behaviour is a disorder? And given the range of similarities between ordinary anti-social behaviour and ordinary social behaviour, should these count or not count towards a judgement that ordinary social behaviours are disorders?

Answering these questions provides a basis for a boundary of the extension of the concept, and so meets the requirement for determination. Where it is judged that resemblances of attributes count for nothing, then the limit of intelligibility in the application of the concept has been reached. And it seems to be reached with the last of the questions in the previous paragraph. It is not intelligible to apply the concept ‘disorder’ to ordinary social behaviour. This is not the same boundary as that, demanded by Horwitz and Wakefield, between things which are and things which are not disorders. It may be considered wrong to think that social deviance is a disorder, but it is not unintelligible. In contrast, it is not so much wrong to think that ordinary social human behaviours are disordered, as it is simply unintelligible. Within a Wittgensteinian framework, the resource from which intelligibility arises is the language game in which the notion of disorder is used. A language game is an activity in which language has a role or roles. That role has to be understood in the context of the game. Clearly, an important part of the language game (or one of the language games) that involves the term ‘disorder’ is the discussion about the limits of the concept ‘disorder’. This part of the language game will include questions such as “is ADHD a disorder?”, “is (so-called) ‘anti-social personality disorder’ really a disorder?” and so on. Within the language game, such questions are serious questions with serious implications. But, there may also be questions which take the same form (“is x a disorder?”) such as “is ordinary social human behaviour a disorder?”, “is happiness a disorder?” and “is having red hair a disorder?”. These are questions that are not asked with the aim of opening a discussion. Rather they are used to bring out the limits of discussion.

We do not, however, have to embrace the Wittgensteinian apparatus of the language game to understand the point that is being made. The form of argument is one relied upon throughout the literature on the definition of disorder: this is simply a reliance upon shared judgements about patterns of human behaviour and experience that are not disorders.Footnote 14

The limit set by intelligibility does not, however, seem to meet the requirement for coherence. Rather, insofar as it allows that both anti-social personality disorder and say an agreed physical disease such as cancer may both be diseases, it seems also to allow that two diseases may have no attributes in common. The criterion of coherence is however, met in the sense that the patterns of shared attributes mean that all diseases have sufficient significant overlaps with at least some other members of the group. This is a more attenuated form of coherence than that found in essentialism. But it does prevent any condition being classed as a disorder which, in fact, turns out to have nothing in common with any condition to which the concept has already been extended.

Someone may object that the appeal to a language game or to agreed usage does not provide a rational basis for inclusion and determination. The objector may note that, as it happens, it is not seriously thought that happiness is a disorder and it is seriously considered that anti-social personality disorder may be, even if it is decided in the end that it is not. But, the objector says, this is a fact about the human practices in this area, not a justification of it. A Wittgensteinian perspective is that this objection is misplaced, as language games are not justifiable by anything outside themselves (Tilghman 1984, p. 170). But it is not necessary to appeal to the Wittgensteinian superstructure here. The objection is to what is perceived as the role of human decisions and practices vis-à-vis the significance of likenesses in the family resemblance approach. But essentialism cannot avoid cognate decisions either. Even if the essentialist were correct that there is a pattern of necessity and sufficiency in the features of those things which are agreed to be disorders, it would be a further decision to conform the notion of ‘disorder’ to that. This decision can’t be justified by the pattern of likenesses itself—since it is the implications of this which are in question; rather it must reflect a human decision or practice. But this is just the same case as with family resemblance.

The family resemblance approach to the concept of disorder accounts for the fact that the significance or meaning assigned to similarities associated with concepts is not given by the presence of similarities among the characteristics of disorder, nor any pattern of necessity and sufficiency they seem to present. In so far as essentialism is committed to the idea that the proposed similarities of attribute or features are the sole determinants of the extension of the concept, it, on the other hand, has made a mistake. Family resemblance is the truer account of conceptual extension.

Secondary sense

An explicit claim that the term ‘disorder’ in ‘mental disorder’ is being used in a secondary sense is to be found in Gipps (2003). He contrasts this with the use of ‘disorder’ to refer to physical disorders, where it is used in its primary sense. Gipps suggests that T.S. Champlin has spelt the idea that the term ‘disorder’ in ‘mental disorder’ is a secondary sense usage out in more detail in his ‘To mental illness via a rhyme for the eye’ (1996). Champlin thinks that mental illnesses are illnesses in the same sense that the words ‘cough’ and ‘bough’ rhyme. Though there are similarities between Champlin’s account and a secondary sense account, there are substantial reasons to doubt that Champlin’s account is a secondary sense account.Footnote 15 The discussion here will be developed independently of Champlin’s account. The rest of this section will describe secondary sense; a subsequent section will consider whether it can meet the criteria of determination and coherence. It will be argued that it cannot: for it abandons the role of resemblances or likeness altogether, and, as a practice, engages in breaking the boundaries of the intelligible use of concepts. This, of course, does not make it a false account of the meaning of ‘disorder’ in the case of mental disorders. Indeed, it can be said to make sense of an inclination in some descriptions of experiences of so-called mental disorder, to use medical descriptions where they do not seem in any straight forward way to be literally applicable.

The notion of secondary sense is attributed to Wittgenstein, most famously in a passage in Part II of Philosophical Investigations.

Given the two ideas ‘fat’ and ‘lean’, would you be rather inclined to say that Wednesday was fat and Tuesday lean, or vice versa? (I incline decisively towards the former.) Now, have “fat” and “lean” some different meaning here from their usual one?—They have a different use.—So ought I really to have used different words? Certainly not that.—I want to use these words (with their familiar meanings) here. …

Asked “What do you really mean here by ‘fat’ and ‘lean’?”—I could only explain the meanings in the usual way. I could not point to the examples of Tuesday and Wednesday.

Here one might speak of a ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ sense of a word. It is only if the word has the primary sense for you that you use it in the secondary one. (Wittgenstein 1992, part II, p. 216e)Footnote 16

The retention of meaning—or at least the fact that no other meaning will do—between the primary and secondary senses of a word, makes secondary sense seem like a means of extending the range of things gathered under a concept. The question is whether extension by this means can be coherent or determinative.

In Wittgenstein’s introduction of the idea of secondary sense, two things are particularly relevant to answering this question. First, while secondary sense involves the use of the familiar meaning of a word,Footnote 17 the use of terms in a secondary sense is to refer to something which does not have any of the characteristics or relations which the primary sense refers to (Diamond 1991, p. 227; Tilghman 1984, p. 160). Wittgenstein implies this when he says that he could not point to Tuesday or Wednesday to explain his usage of ‘lean’ and ‘fat.’ So, the extension of the term ‘fat’ is not justified by or even associated with any commonalities or likenesses between those things referred to in the primary usage of the term and those things referred to in the secondary usage of the term.

Second, in some cases of secondary sense uses of words, not just one term but a whole group of terms and their interrelations are involved. Wittgenstein refers to two terms which have meanings related to one another: ‘fat’ and ‘lean’. This list might be extended further, to include, say ‘well-built’, ‘muscular’ and other related descriptions. A common way of expressing this point is to speak of the secondary use of the terms in a language game (Tilghman 1984, p. 178; ter Hark 2009, p. 601). As before, we don’t have to accept this particular piece of Wittgensteinian superstructure to see the point. Hanfling (2002) considers the description of a piece of music deploying an interrelated group of terms used in a primary sense to refer to human verbal intercourse. He comments: “such words as ‘assertion’, ‘question’, ‘confirmation’, ‘inference’, etc., are interconnected in logical ways that cannot occur in a piece of music” (p. 157). The terms, with their meanings and interconnections nonetheless survive into the secondary sense: passages of music referred to as questions may be answered by others. The fact that a group of terms with their logical connections is often deployed in secondary sense has been put forward as a basis for limiting what and where secondary sense can be used to describe. This is a matter for further discussion below.

Prior to that, a question arises as to whether secondary sense is anything other than word play. In the musical examples, there is good reason to think it is more. For example, a listener may hear a passage of music differently after it is described to her as a question. This possibility is linked in Wittgenstein’s writing to “aspect perception” or “seeing an aspect” or, seeing something ‘as’ something (1992, part II, pp. 194eff). (In the case of music it might be hearing rather than seeing an aspect: hearing an instrumental passage of music as a question, and another as an answer to it.) In aspect perception, or seeing as, what changes is something in the perceiver.Footnote 18 Wittgenstein, for example, talks of the way an aspect can dawn upon someone. When it dawns on someone that certain passages in a piece of music are question and answer, this does not alter anything in the music—for example, exactly the same CD recording may be involved before and after; and yet, for one who perceives the music in this way, the music will be experienced differently to before.

Then, why use terms such as ‘seeing’ and aspect ‘perception’? For both these suggest that something—an attribute or characteristic of the object—has been seen or perceived. The notions of aspect ‘seeing’ and secondary sense are in fact quite entangled. In the concepts of aspect ‘perception’ or ‘seeing’, these terms are themselves being used in a secondary sense. Aspect perception or seeing an aspect is not like spotting a boat on the other side of the harbour, though the primary meaning of the term seeing still seems to be the appropriate meaning to deploy. It is more like seeing the stars in Orion as a constellation: the aspect is in the viewer. What is in the viewer is not a characteristic of the thing viewed; an aspect of something is not a characteristic of it.

Suppose physical disorder and associated concepts and their interrelations constitute the primary sense of the concept of disorder, and the extension to mental disorder is being considered. If the extension is by means of a secondary sense of disorder, then schizophrenia, anti-social personality disorder, alcoholism and so on will not be disorders in virtue of any characteristic(s) they have in common with say pneumonia, influenza, multiple sclerosis or cancer. They will be disorders in the sense that they may be seen as disorders, or be seen under that aspect. Being seen under this aspect, they will be describable in linked groups of terms used to describe disorders. For example, in talking about schizophrenia someone may be inclined to use terms such as ‘diagnosis’, ‘treatment’, ‘symptoms’ and ‘causes’. All these are used in their primary senses in physical disorder. But, if schizophrenia is a disorder in a secondary sense, then each of these logically interrelated descriptors will be used in a secondary sense too. In physical disorder there are symptoms, but in mental disorder there are symptoms in a secondary sense.

At first sight the idea may seem obviously wrong, in that it appears a plain mistake to assert that for example delusions, or the low moods of depression, are not symptoms in the primary sense of that term. To say that something is a symptom in a primary sense is generally to relate it causally to whatever it is symptomatic of. The symptom will mean the disorder in the way focused lower back pain which cannot be relieved either by moving or by over-the-counter painkillers, may mean a kidney stone. It may be claimed that this seems to be the case with delusions, low mood and so on. To say that low mood is a symptom of depression is simply to say that it is caused by depression; to say a delusion is a symptom of schizophrenia is simply to say that it is caused by schizophrenia.

However, in the context of the experiences of sufferers of mental disorders, it is not clear the term ‘symptoms’ is rightly used in its primary sense. Consider the experience of John Stuart Mill of what is now sometimes diagnosed as a major depressive episode (Mill 2003, p. 1347). If this is ‘mental disorder’ in its primary usage, then Mill’s anguished experiences (described in his Autobiography as “A crisis in my mental history” (Mill 1969, pp 112ff)) would presumably be ‘symptomatic’ (again in its primary sense) of this disorder. They would be understood as caused by it. But for Mill his experience was life changing. Mill describes himself in this period as wrestling with a genuine problem for the utilitarian position and emerging with “very marked effects on my opinion and character” (Mill 1969, p. 120). It may be suggested that only a secondary sense usage of the term ‘symptom’ could successfully deploy its primary meaning in such a different context.

An alternative to the idea that delusions are symptoms in this primary sense also exists, which Chung traces back to Jaspers.

His [Jaspers’] main task in his general psychopathology was precisely to organise or assess patients’ internal experiences around a core of meaningfulness, regardless of nosographical attributions. Thus, psychopathology is seen as patients’ attempts to describe themselves or express their own experience. (Chung 2007, p. 36)

The meaningfulness of peoples’ account of their internal experiences relates to their articulation of themselves. What people says about themselves isn’t caused by themselves or any of their parts, so primary uses of the term ‘disorder’ and related terms such as ‘symptoms’ seems out of place.

The argument, then, is that in its primary sense, symptom implies indications of disorder because the symptom is caused by the disorder. So far is this from what low moods and delusions may mean, that only a secondary sense use of the term ‘symptom’ seems to make sense in descriptions of such experiences of personal crisis and self-expression. Nonetheless, ‘symptom’ with this primary meaning used in a secondary sense is the right word to use.

Secondary sense and the valid extension of concepts

Up to now, the retention of meaning between primary and secondary senses has been taken to justify raising the question whether disorder in a secondary sense is an extension of the notion of disorder. But it remains to be seen if this supposed form of extension can meet the criteria for valid extension of determination and coherence. There is no characteristic or attribute of the disorders referred to in the secondary sense which may be associated with an extension of this sort. So, the search for determination and coherence, if they are to be found, cannot be focussed on the characteristics or attributes of physical and mental disorders.

In family resemblance the criteria for valid concept extension are met by the limits of intelligibility of applying a concept, in turn based upon the simple enough idea that some things clearly are not disorders. In secondary sense, the conditions are met by the limits of aspect perception. Determination and coherence set out to prevent two things. Determination sets out to prevent extensions of a concept which are too wide or too restricted. If the use of the term ‘disorder’ and associated terms to describe an aspect is restricted to only some sorts of thing, then this would constitute a determination of the concept, as it would produce a bounded group. Coherence sets out to capture a sense of being part of the same group. If the meaning which describes those things under the aspect of disorder is continuous with the meaning in the primary use of those terms, then this suggests a reason for thinking mental and physical disorder belong in the same group.

But, while these mark out in a formal way the means by which aspect perception may meet the criteria of determination and coherence, it relocates rather than resolves the problem. It does not explain how the perception of something as a disorder may be restricted to certain sorts of things (in order to meet the criterion of determination) nor how seeing a human behaviour under the aspect of disorder reflects a sense that they should be grouped together (in order to meet the criterion of coherence). Is there any reason why for example ordinary human happiness, or social behaviours, should not be seen under the aspect of—seen as—a disorder?

In fact, it will be argued there is not. Three ways in which the perception of aspects may be thought to be constrained can be considered: these relate to intelligibility, communicability and articulability. However, none of these provides any basis of determination or coherence.

Intelligibility

It is not intelligible, it was suggested earlier, to designate ordinary human happiness or social activity disordered. But such absence of intelligibility does not operate to restrict aspect perception. The unintelligibility of ordinary human happiness, for example, being designated a disorder relates to disorder used in its primary sense. Perhaps referring to one passage of music as a question and another as an answer to it is unintelligible in the primary senses of these terms. But an aspect may be conveyed despite this through the secondary sense of these terms. Secondary sense does not abide by any rules (or other forms of limits) there might be for primary sense; indeed, use in the secondary sense seems to entail that such limits are broken.

Non-arbitrariness

Wittgensteinian scholars have accepted that secondary sense uses are not rule bound, but argued that notwithstanding secondary sense is not an undisciplined or arbitrary usage of language (for instance, Tilghman 1984, p. 168). The discipline is created by the retention of primary meaning, and the involvement of interconnected networks of concepts. It might be added that also required is the ability to use meanings in secondary senses.Footnote 19 In Wittgensteinian terminology, we might say that the communication of aspects (e.g. helping others to see them) depends on being able to play this particular language game; but we don’t need to use the Wittgensteinian architecture to understand the point.

However, the discipline implied by the use of the primary meaning of a word or group of words does not appear to be a restriction on its use: rather it is what makes secondary sense possible. This is what is required in order to communicate an aspect from one person to another. Retention of the primary meaning of a term or conceptually related groups of terms may be found in the case of, say, using disorder to describe schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, but they may also be met in using disorder to describe any number of other things.

Articulability

It may be argued that there must be some restrictions on aspect perception to things which have some broad similarities in structure. Only in such cases, it may be suggested, can the secondary sense of a set of terms which are related to one another in their primary senses bring out or articulate the perception of aspects. In the music examples, the secondary senses of question and answer seem to make sense where the primary activity is one form of communication, between people, and the description applies secondarily to another form of communication plausibly involving different voices (in the form of different instruments or sections of the orchestra, for example). Perhaps, parallel to this, the primary senses of the term disorder can be used in secondary senses to articulate only such things as behavioural patterns and linguistic communications. However, no restrictions of this kind appear to apply to the use of ‘fat’ to describe a person’s body and to describe a day of the week. Furthermore, even if there were some restriction to aspects of ‘human behaviour’ or similar, this doesn’t seem restrictive enough. It may reasonably be argued that some human behaviours must be beyond the reach of the notion of disorder. If none is, it is difficult to see what distinction among behaviours the concept disorder can make.

There seems to be no basis for restricting aspect perception, and hence for restricting secondary sense uses of words such as disorder, symptom. It is true, as with the musical examples, that some aspects are commonly recognised and discussion about them proceeds. Secondary sense is required in understanding some human behaviours, and this comes out in the way language is actually deployed in those areas. The use of ‘disorder’, ‘symptom’ etc. in mental disorder may be an example of this. And, as a matter of fact, these terms are not used with a secondary sense (nor a primary sense) in describing other behaviours, such as ordinary human social behaviour. But this is not because they cannot be; rather, the limit of use is a contingent fact.

Conclusion

Valid extension of a concept includes meeting a criterion of determination, and a criterion of coherence. Both family resemblance and secondary sense eschew the essentialist reliance on characteristics to meet these criteria.

Family resemblance provides a basis in the notion of intelligibility. Intelligibility is not the sort of basis for extension which essentialists recognise: but it constitutes a basis nonetheless, and it is this which is required to make family resemblance a basis for the extension of disorder. In referring to intelligibility, family resemblance recognises the inevitable role of human judgements in the use of concepts. The essentialist’s focus on the features, characteristics or attributes of disorders as providing the sole basis of extension is mistaken

Secondary sense, while it provides that the extension is restricted by the limits of aspect perception, does not provide any basis for limiting this, and so it does not meet the criteria for valid extension. Logical requirements for the possibility of using primary meanings in a secondary sense have been proposed, but they appear to allow that almost any human behaviour may be described as disordered. It cannot be ruled out that secondary sense captures a tension at the heart of attempted extensions of disorder from the physical to the mental: that is to say, the secondary sense approach to mental disorder may be the right one. But if it is, then mental disorder is not an extension of physical disorder.

Notes

Cf. Jensen (1984, p. 63) who describes essentialism in medicine as implying that “terms referring to entities have to be defined by specifying a conjunction of characteristics, each of which are necessary, and which together are sufficient for the use of the term”.

It is sometimes noted (as in the comments of one of the anonymous reviewers of this paper) that the criteria for the various diagnoses in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association appear to have features of family resemblance concepts. For example, fifteen attributes are associated with Conduct Disorder, but to be diagnosed a child need have only three of these (McNally 2011, p. 188). Shorter (2009), focusing on Major Depressive Disorder, describes this as a ‘Chinese menu’ approach (p. 158). My focus is on the attributes of mental disorder, however, and neither DSM nor Shorter offer a family resemblance account of this concept.

McNally mentions Wittgenstein’s insight that “examples of most useful concepts bear only a family resemblance to one another” (McNally 2011, p. 212) but when he unpacks this insight it becomes clear that he understands family resemblance in Roschian terms, suggesting, for example, that “the more attributes [associated with the concept] a given case has, the better example it is of the concept” (p. 212). The slide from family resemblance to Roschian approaches is understandable. Rachel Cooper referring to the work of Lilienfeld and Marino (1995) says their Roschian approach is “very close to” a family resemblance analysis (Cooper 2007, pp. 41, 43; see also Wakefield, 1999, p. 375). However, Cooper’s own approach to family resemblance appears to be Roschian (2007, p. 8). Rosch was inclined to link her analysis with that of Wittgenstein (cf. Rosch and Mervis 1975, pp. 574–575). Sadegh-Zadeh (2008) rightly makes a clear distinction, and while acknowledging that there are some truths in the family resemblance approach rejects it in favour of his own form of prototype resemblance account.

This is a complex area, which cannot be pursued in detail here. For a different view of family resemblance see ter Hark (1990 p. 149).

The terms ‘similarity’, ‘feature’, ‘characteristic’ and ‘attribute’ will be used interchangeably.

The idea that there is a set of characteristics associated with the concept is a useful simplification of family resemblance for the purposes of this paper. For a more complex account see Beardsmore 1992, p. 136ff.

Weitz, using the notion of open concepts, offers a similar analysis (1956, pp 27–35). Weitz comments that the verdict on whether Finnegan’s Wake is a novel “turns on whether or not we enlarge our set of conditions for applying the concept”.

This list reflects various criteria that have been mentioned and used in the literature seeking to define ‘disorder’ or cognate concepts. In seeking to reflect this literature, I have not restricted the attributes to descriptive criteria. They tend towards the abstract, because they reflect criteria for disorder in general.

Criterion A for schizophrenia in DSM-IV-TR includes delusions; and schizophrenia (paranoid type) focuses on delusions and auditory hallucinations.

Bentall’s aim is to show that if we rely on shared factual characteristics, and ignore obvious evaluative aspects of the notion disorder (viz. that disorders are things we disvalue) we may be forced to conclude absurdly that ordinary human happiness is a disorder.

A potential counter-example to my claim here would be a notion of family resemblance that extended to include Richard Boyd’s homeostatic property clusters (Boyd 1989, 1991). Boyd’s favourite example is ‘species’. There is however some debate about whether Boyd’s clusters are examples of family resemblances (Hacking 1991); and no one has to my knowledge proposed that disorder is a homeostatic property cluster.

A proposed ‘solution’ to the problem of the under-determination of extension offered by Andersen (2000) and based on the work of Thomas Kuhn involves contrast concepts. The exact relationship between Andersen’s approach and the one offered here has to be determined.

Champlin does not use the term secondary sense to characterise his own account, which implies that he does not think it is such an account. More significantly, Champlin’s main analogy for the relation of the idea of physical and mental illness (a rhyme for the ear and a rhyme for the eye) does not appear to involve a secondary sense use of rhyme.

Though there is some debate about this. For the contrary view see Bar-Elli (2006, p. 223).

Wittgenstein discusses ‘aspect blindness’ (1992, part II, pp. 213–214e) which, given the role of secondary sense in aspect perception and its communication, would imply insensitivity to secondary sense uses of language.

References

American Psychiatric Association. 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edition Text Revision. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349.

Andersen, H. 2000. Kuhn’s account of family resemblance: A solution to the problem of wide-open texture. Erkenntnis 52: 313–337.

Angell, M. 2011a. The epidemic of mental illness: why? The New York Review of Books 23 June. On line http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/jun/23/epidemic-mental-illness-why/. Accessed 21 Sep 2011.

Angell, M. 2011b. The illusions of psychiatry. The New York Review of Books 14 July. On line http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/jul/14/illusions-of-psychiatry/. Accessed 21 Sep 2011.

Bambrough, R. 1970. Universals and family resemblances. In Modern studies in philosophy: Wittgenstein. The philosophical investigations, ed. G. Pitcher, 186–204. London: Macmillan and Co Ltd.

Bar-Elli, G. 2006. Wittgenstein on the experience of meaning and the meaning of music. Philosophical Investigations 29: 217–249.

Beardsmore, R.W. 1992. The theory of family resemblances. Philosophical Investigations 15: 131–146.

Bellaimey, J.E. 1990. Family resemblances and the problem of the under-determination of extension. Philosophical Investigations 13: 31–43.

Bentall, R.P. 1992. A proposal to classify happiness as a psychiatric disorder. Journal of Medical Ethics 18: 94–98. doi:10.1136/jme.18.2.94.

Boorse, C. 1977. Health as a theoretical concept. Philosophy of Science 44: 542–573.

Boorse, C. 1982. What a theory of mental health should be. In Psychiatry and ethics: Insanity, rational autonomy, and mental health care, ed. R.B. Edwards, 29–48. Buffalo: Prometheus Books.

Boorse, C. 1997. A rebuttal on health. In What is disease?, ed. J. Humber, and R. Almeder, 3–134. Totowa: Humana Press.

Boyd, R. 1989. What realism implies and what it does not. Dialectica 43(1–2):1 (6–29).

Boyd, R. 1991. Realism, anti-foundationalism and the enthusiasm for natural kinds. Philosophical Studies 61: 127–148.

Brody, H. 1985. Philosophy of medicine and other humanities: Toward a wholistic view. Theoretical Medicine 6: 243–255.

Brülde, B. 2010. On defining “mental disorder”: Purposes and conditions of adequacy. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 31: 19–33. doi:10.1007/s11017-010-9133-1.

Champlin, T.S. 1996. To mental illness via a rhyme for the eye. In Verstenhen and humane understanding, ed. A. O’Hear, 165–189. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chung, M.C. 2007. Conceptions of schizophrenia. In Reconceiving schizophrenia, ed. M.C. Chung, K.W.M. Fulford, and G. Graham, 29–62. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clouser, K.D., C.M. Culver, and B. Gert. 1981. Malady: A new treatment of disease. Hastings Center Report 11(3): 29–37.

Cooper, R. 2002. Disease. Studies in the history and philosophy of biological and biomedical sciences 33: 263–282.

Cooper, R. 2007. Psychiatry and the philosophy of science. Stocksfield: Acumen Publishing Ltd.

Culver, C.M., and B. Gert. 1982. Philosophy in medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

Davidson, D. 2001. What metaphors mean. In Inquiries into truth and interpretation, 245–264. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davidson, D. 2005. A nice derangement of epitaphs. In Truth, language, and history, 89–107. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Diamond, C. 1991. Secondary sense. In The realistic spirit, 225–241. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Engelhardt, H.T. 1975. The concepts of health and disease. In Evaluation and explanation in the biomedical sciences, ed. H.T. Engelhardt, and S.F. Spicker, 125–141. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Engelhardt, H.T. 1976. Ideology and etiology. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 1(3): 256–268.

Engelhardt, H.T. 1984. Clinical problems in the concept of disease. In Health, disease, and causal explanations in medicine, ed. Lennart Nordenfelt, and B.I.B. Lindahl, 27–41. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Frances, A.J. 1980. The DSM-III personality disorders section: A commentary. American Journal of Psychiatry 137: 1050–1054.

Fulford, K.W.M. 1989. Moral theory and medical practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gipps, R. 2003. Illnesses and likenesses. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 10: 255–259.

Hacking, I. 1991. On boyd. Philosophical Studies 61: 149–154.

Hanfling, O. 2002. Wittgenstein and the human form of life. London: Routledge.

Hogan, J. 2006. Pluto: The backlash begins. Nature 442: 965–966. doi:10.1038/442965a.

Horwitz, A.V. 2002. Creating mental illness. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Jensen, U.J. 1984. A critique of essentialism in medicine. In Health, disease, and causal explanations in medicine, ed. L. Nordenfelt, and B.I.B. Lindahl, 63–73. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Joseph, J. 2003. The gene illusion: Genetic research in psychiatry and psychology under the microscope. Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books.

Kirov, G., and M.J. Owen. 2009. Genetics of Schizophrenia. In Kaplan and Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 9th ed, ed. B.J. Sadock, V.A. Sadock, and P. Ruiz, 1462–1475. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Lilienfeld, S.O., and L. Marino. 1995. Mental disorder as a Roschian concept: A critique of Wakefield’s “harmful dysfunction” analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 104: 411–420.

Lucire, Y. 2003. Constructing RSI Belief and desire. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, Ltd.

McNally, R.J. 2011. What is mental illness?. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

van Marle, H., and N. Eastman. 1997. Psychopathic disorder and therapeutic jurisprudence. In Challenges in forensic psychotherapy, ed. H. van Marle. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Mill, J.S. 1969. Autobiography. London: Oxford University Press.

Mill, J.S. 2003. Personal accounts: A crisis in my mental history (with introduction by column editor J.L. Geller). Psychiatric Services 54(10): 1347–1349. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/.

Moran, P. 1999. The epidemiology of antisocial personality disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34: 231–242.

Murray, R.M., and D.J. Castle. 2009. Genetic and environmental risk factors for schizophrenia. In New Oxford textbook of psychiatry.2nd edition, 553–561. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Murphy, D. 2006. Psychiatry in the scientific image. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nordenfelt, L. 2007. Concepts of health and illness revisited. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 10: 5–10.

Pitcher, G. 1964. The philosophy of Wittgenstein. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, Inc.

Reznek, L. 1987. The nature of disease. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Rosch, E., and C.B. Mervis. 1975. Family resemblances: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology 7: 573–605.

Sadegh-Zadeh, K. 2008. The prototype resemblance theory of disease. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 33: 106–139. doi:10.1093/jmp/jhn004.

Schilling, G. 1999. Pluto: The planet that never was. Science 283(5399): 157. doi:10.1126/science.283.5399.157.

Schilling, G. 2006. Underworld character kicked out of planetary family. Science 313: 1214–1215.

Sheppard, S.S. 2006. A planet more, a planet less? Nature 439: 541–542.

Shorter, E. 2009. Before Prozac. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Szasz, T. 1960. The myth of mental illness. The American Psychiatrist 15: 113–118.

ter Hark, M. 1990. Beyond the inner and the outer Wittgenstein’s philosophy of psychology. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

ter Hark, M. 2009. Coloured vowels: Wittgenstein on synaesthesia and secondary meaning. Philosophia 37: 589–604. doi:10.1007/s11406-009-9194-4.

Tilghman, B.R. 1984. But is it art?. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Publisher, Ltd.

Wakefield, J.C. 1992a. The concept of mental disorder: On the boundary between biological facts and social values. American Psychologist 47(3): 373–388.

Wakefield, J.C. 1992b. Disorder as a harmful dysfunction: A conceptual critique of DSM-III-R’s definition of mental disorder. Psychological Review 99(2): 232–247.

Wakefield, J.C. 1999. Evolutionary versus prototype analysis of the concept of disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108(3): 374–399.

Weitz, M. 1956. The role of theory in aesthetics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism XV: 27–35.

Wittgenstein, L. 1992. Philosophical investigations. 3rd edition (trans: Anscombe, G.E.M.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell Publisher, Ltd.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Tim Thornton, Lynn Bowyer and Stacey Broom, staff and students of the Bioethics Centre at the University of Otago, and the anonymous reviewers of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pickering, N. Extending disorder: essentialism, family resemblance and secondary sense. Med Health Care and Philos 16, 185–195 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-011-9372-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-011-9372-6