Abstract

In this essay I will defend the thesis that proper nouns are primarily used as proper names—as atomic singular referring expressions—and different possible predicative uses of proper nouns are derived from this primary use or an already derived secondary predicative use of proper nouns. There is a general linguistic phenomenon of the derivation of new meanings from already existing meanings of an expression. This phenomenon has different manifestations and different linguistic mechanisms can be used to establish derived meanings of different kinds of expressions. One prominent variation of these mechanisms was dubbed in Nunberg. (Linguist Philos 3:143–184, 1979, J Semant 12:109–132, 1995, The handbook of pragmatics. Blackwell, Oxford, 2004 meaning transfer.) In the essay I will distinguish two different sub-varieties of this mechanism: occurrent and lexical meaning transfer. Nunberg conceives of meaning transfer as a mechanism that allows us to derive a new truth-conditional meaning of an expression from an already existing truth-conditional meaning of this expression. I will argue that most predicative uses of proper nouns can be captured by the mentioned two varieties of truth-conditional meaning transfer. But there are also important exceptions like the predicative use of the proper noun ‘Alfred’ in as sentence like ‘Every Alfred that I met was a nice guy’. I will try to show that we cannot make use of truth-conditional meaning transfer to account for such uses and I will argue for a the existence of second variant of meaning transfer that I will call use-conditional meaning transfer and that allows us also to capture these derived meanings of proper nouns. Furthermore, I will try to show that the proposed explanation of multiple uses of proper nouns is superior to the view supported by defenders of a predicative view on proper names.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cf.: Rami (2014a, 856–861).

Cf.: Boer (1975, 390).

Cf.: Nunberg (1995, 112).

According to Nunberg, this feature distinguishes metonymies from metaphors. Cf.: Nunberg (1995, 113).

Cf. Nunberg (1995, 112–13).

Cf.: Nunberg (2004, 351–354).

Cf.: Nunberg (1995, 115).

Cf.: Nunberg (1995, 116–119).

Cf.: Nunberg (1995, 117).

Cf.: Fara (2012, 11–13).

Nunberg points out that these rules might have exceptions, because they are subject to general conditions of noteworthiness. Cf.: Nunberg (1995, 117).

Cf.: Nunberg (1995, 116–119).

Cf.: Boer (1975, 391).

One additional problem of an interpretation of original uses of a noun like ‘Alfred’ on the basis of metalinguistic occurrent transfer has to do with the plural of ‘Alfred’ that seems to be required to interpret a sentence like ‘Some Alfreds are nice’ in an adequate way. It is not clear how we account for this kind of plural on the basis of the metalinguistic view in an adequate way. C.f: Jeshion (2013, 16–17).

This account is defended in Leckie (2012, 15–21).

Cf.: Leckie (2012, 7–10, 15–16).

The same problem, for example, would affect a proposal that holds that ordinary proper names are ambiguous and tries to capture the meaning of ‘is an Alfred’ according to its original use on the basis of a disjunction like ‘x = Alfred1 or x = Alfred2 or … or x = Alfredn‘. Such a proposal also has an additional problem, because there can be objects that do not bear the name ‘Alfred’ in the actual world, but bear this name in some different possible world.

This possibility was pointed out to me by an anonymous referee.

I have found evidence for both kinds of derived predicative uses of the pronouns ‘she’ and ‘he’.

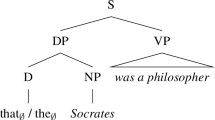

This account can be combined with different possible treatments of semantics of the definite article.

Kaplan’s famous dthat-operator has a similar contribution to truth-condition as the combined modifiers ‘actual’ and ‘present’. That is, ‘dthat(the president of Germany)’ is truth-conditionally equivalent with ‘the actual and present president of Germany’. Cf.: Kaplan (1989[1977], 546).

Cf.: Corazza (2002, 183, 189).

Cf.: Potts (2005).

Cf.: Predelli (2013, 26–30).

Cf.: Rami (2014b).

Cf.: Hawthorne and Manley (2012, 11).

Cf.: Predelli (2013, 13–14).

Cf.: Predelli (2013, 186–187).

Cf.: Corazza (2002, 173–175).

Cf.: Corazza (2002, 175–179).

Cf.: Kripke (1977, 263).

Cf.: Corazza (2002, 191).

It seems to be possible to generalize this lexical rule in the following way: (G5*) If a third person personal pronoun ‘N’ is used as a singular referring expression that has the condition expressed by ‘is F’ as a constraining constituent of its use-conditional meaning, then ‘N’ can also be used as a predicate that is truth-conditionally equivalent with ‘is F’.

Cf.: Predelli (2013, 68).

This example was pointed out to me by an anonymous referee.

An anonymous referee objected to my proposed alternative mechanism of use-conditional meaning transfer that it leads to an overgeneralisation of the availability of derived predicative expressions. For example, someone might argue that in the case of indexical expressions like ‘I’ or ‘you’ it also seems to be plausible to assume an additional use-conditional component of meaning besides their truth-conditional meaning. Hence, one may claim that it is only then adequate to use the expression ‘I’ (‘you’) relative to a context of use if one refers to the speaker of the context of use (the addressee of the context of use) by means of this expression. But interestingly there are no predicative uses of ‘I’ and ‘you’ that are similar to the mentioned predicative uses of ‘he’ and ‘she’. I cannot meaningfully say, ‘There are lots of Is/mes here’ and thereby mean, ‘There are a lots of speakers here’. And I also cannot meaningfully say ‘There are lots of yous here’ and thereby mean ‘There are lots of addresses here’. Someone might now claim in the light of the absence of such derived predicative uses of certain indexical expressions that it is doubtful that our proposed alternative mechanism of meaning transfer exists at all. But this objection is based on a misunderstanding. Firstly and most importantly, I didn’t claim that every expression that has a use-conditional meaning that constrains the adequate contexts of use of such an expression automatically also has an additional derived predicative use whose truth-conditional content is determined by some component of the original constraining condition. It requires an established use of competent speakers that exploits the use-conditional meaning of a certain expression in the described way. And only if such an established use is conventionalized by a lexical rule like (G5) or (G6), a genuine form of lexical meaning transfer from the use-conditional to the truth-conditional level is established. Secondly, one might doubt in the case of the (automatic) indexical ‘I’ and ‘you’ whether the mentioned speaker- and addressee-conditions are really part of the use-conditional meaning of such an expression. It seems in their case more plausible to conceive of these conditions as part of the Kaplanian-character of these expressions.

There is one problem that seems to indicate that our formulation of the lexical rule that regulates the original predicative uses of proper nouns in natural language might need further adaptations. In the case of names for persons, we can distinguish first-names and family-names. Sometimes if we use the corresponding predicates of these names in generalisations like, ‘Every Alfred that I met in school was a fool’, or, ‘Every Smith is a bearer of a widespread family-name,’ we use these predicates in a more restricted sense. Relative to such uses ‘is an Alfred’ is equivalent to ‘is a bearer of the first-name ‘Alfred’’ and ‘is a Smith’ is equivalent to ‘is a bearer of the family-name ‘Smith’’. We can regard these uses as examples of quantifier domain restriction or we might adapt the rule (G6) in such a way that first and family names are treated in different ways. I just wanted to mention this problem here and leave it to future research.

These two mechanism differ in the way how they establish a new derived meaning, but both mechanisms share the feature that they produce as a result certain more or less specific lexical rules that conventionalize the meaning transfer.

According to such an analysis, a universal generalisation of the form ‘Every F is G’ implies ‘Something is an F’.

Cf.: Burge (1973, 429).

Cf.: Matushansky (2008, 603–609).

A similar observation is attributed in Hawthorne and Manley (2012, 229) to Aidan Gray.

Aidan Gray suggested this reply to me in personal communication.

References

Boër, S. E. (1975). Proper names as predicates. Philosophical Studies, 27, 389–400.

Borg, E. (2000). Complex demonstratives. Philosophical Studies, 97, 229–249.

Braun, D. (1994). Structured character and complex demonstratives. Philosophical Studies, 74, 193–219.

Burge, T. (1973). Reference and proper names. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 425–439.

Corazza, E. (2002). ‘She’ and ‘He’: Politically correct pronouns. Philosophical Studies, 111, 173–196.

Cumming, S. (2008). Variablism. Philosophical Review, 117, 525–554.

Dever, J. (1998). Variables. Berkeley: PhD Dissertation University of California.

Elbourne, P. (2005). Situations and individuals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Elugardo, R. (2002). The predicate view of proper names. In G. Preyer & G. Peter (Eds.), Logical form and language (pp. 467–503). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fara, D. G. (2012). “Literal” uses of proper names. In A. Bianchi (Ed.), On reference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (forthcoming).

Hawthorne, J., & Manley, D. (2012). The reference book. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hornsby, J. (1976). Proper names: A defense of Burge. Philosophical Studies, 30, 227–234.

Jeshion, R. (2013). The uniformity argument for predicativism about proper names (unpublished manuscript).

Kaplan, D. (1977). Demonstratives. In J. Almog, J. Perry, & H. Wettstein (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan (pp. 481–563). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kripke, S. (1977). Speaker’s reference and semantic reference. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 2, 255–276.

Leckie, G. (2012). The double life of names. Philosophical Studies, 1–22. doi:10.1007/s11098-012-0008-3.

Lepore, E., & Ludwig, K. (2000). The semantics and pragmatics of complex demonstratives. Mind, 109, 199–240.

Matushansky, O. (2008). On the linguistic complexity of proper names. Linguistics and Philosophy, 31, 573–627.

Nunberg, G. (1979). The non-uniqueness of semantic solutions: Polysemy. Linguistics and Philosophy, 3, 143–184.

Nunberg, G. (1995). Transfer of meaning. Journal of Semantics, 12, 109–132.

Nunberg, G. (2004). The pragmatic of deferred interpretation. In L. R. Horn & G. Ward (Eds.), The handbook of pragmatics (pp. 344–364). Oxford: Blackwell.

Potts, C. (2005). The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Predelli, S. (2013). Meaning without truth. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Rami, D. (2014a). On the unification argument for the predicate view on proper names. Synthese, 191, 841–862.

Rami, D. (2014b). The use-conditional indexical conception of names. Philosophical Studies, 168, 119–150.

Recanati, F. (2004). Literal meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richard, M. (1993). Articulated Terms. Philosophical Perspectives, 7, 207–230.

Sawyer, S. (2010). The modified predicate theory of proper names. In S. Sawyer (Ed.), New waves in philosophy of language (pp. 206–225). Palgrave: MacMillan Press.

Sloat, C. (1969). Proper nouns in English. Language, 45, 26–30.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rami, D. The Multiple Uses of Proper Nouns. Erkenn 80 (Suppl 2), 405–432 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-014-9704-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-014-9704-z