Abstract

This study investigated entrepreneurs’ motivations to implement circular economy (CE) practices and the ways in which their approaches to CE practices differed by their sociocultural context. The research aimed to contrast the contemporary instrumental perspective on CE through an ecologically dominant logic. The empirical analysis focused on Finland and Japan, two countries with distinct sociocultural contexts but similar regulatory environments regarding the CE. The study analysed entrepreneurs’ motivations towards the CE through self-determination theory that makes a distinction between different levels of internalization in motivations. The Finnish entrepreneurs were characterised by more frequent intertwined intrinsic/transcendent motivations and a vocal approach to CE. The Japanese entrepreneurs’ motivations were more varied; some were intrinsically interested in the CE, while some were even unaware of the CE concept despite operating CE businesses. The Japanese entrepreneurs resorted to masking their CE businesses to better relate with the surrounding linear system. The study shows how the individualistic Finnish culture fostered progress on the CE, while the collectivistic Japanese culture emphasised the need for relatedness and caused stagnation in the CE in its society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A circular economy (CE) has been suggested as a possible response to the global climate crisis. Being a sustainable alternative to the dominating take-make-dispose logic of the linear economy (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Frei et al., 2020; Ghisellini et al., 2016; Koh et al., 2017; Moosmayer et al., 2020; Smart et al., 2017), a CE has the potential to change the fundamental logic of production and consumption (Ness, 2008). Building on The Brundtland Commission’s definition of sustainability (WCED, 1987), the underlying aim of CE is sustainable development “that meets the needs of the present while safeguarding Earth’s life-support system, on which the welfare of current and future generations depends” (Griggs et al., 2013, p. 306). However, currently, the CE is largely viewed through an instrumental logic that seeks economic benefit from environmentally friendly activities (Corvellec et al., 2021). Such an instrumental view carries the risk of the inherent ethical characteristics of CE being overlooked and superseded by business considerations.

Companies have been identified as playing a key role in successful CE implementation in society (Brennan et al., 2015; MacArthur, 2013). Accordingly, entrepreneurs are in a crucial position in the expansion of the CE in society, as well as in enabling the scientific community to understand why and how CE practices are being implemented (Gioia, 2019; Gioia et al., 2013). A crucial prerequisite for entrepreneurs’ actions on the CE (Hayamizu, 1997; Seguin et al., 1998) is their related motivations (Gagné & Deci, 2005), according to self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1991, 2000). Internalised motivation is associated with more effective performance and greater behavioural persistence (Hayamizu, 1997; Ryan et al., 1993). Further, this paper assumes that some entrepreneurs’ motivations for CE are not based on instrumental logic, but rather some may view it as an end in itself, which the previous research has not explicitly considered (Henry et al., 2020; Rovanto & Bask, 2021). There is anecdotal evidence that entrepreneurial companies may have broader and more encompassing applications of CE together with genuine motivations towards the well-being of other people and of the natural surroundings (Rovanto & Bask, 2021). Entrepreneurs’ motivations for CE can be argued to be an important determinant of CE approaches and help shape the direction of the CE in society.

What exactly motivates entrepreneurs around the world to implement CE practices is currently not well understood. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the CE literature (e.g., Ghisellini et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2017) has not explored these motivations but only the drivers of CE adoption. These drivers have been divided into external (legislation, competitor pressure, supply chains, global environmental trends, etc.) and internal ones (top management commitment to a CE, cost reduction, economic growth, an organisational culture that supports a CE, etc.) (Jia et al., 2020; Levänen et al., 2018; Moktadir et al., 2018). This study takes a step further by examining and classifying entrepreneurs’ different types of motivations for a CE. The entrepreneurs’ motivations are examined here on a continuum from intrinsic/transcendent motivation through four types of extrinsic motivations with different levels of internalisation all the way to amotivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Gagné & Deci, 2005; Melé et al., 2019; Rosanas, 2008). The empirical findings of this study are expected to contribute to the understanding of what sparks an entrepreneur to implement CE practices at their company.

To understand more closely how motivation towards a CE may manifest itself in actions, different types of approaches to the implementation of CE practices need to be studied. Sociocultural support towards a CE, meaning the informal norms and culture in a society, is expected to be in a key position in shaping approaches to a CE, and this support will differ based on each sociocultural environment (Green-Demers et al., 1997; Hayamizu, 1997; Ryan et al., 1993; Seguin et al., 1998). In particular, according to SDT, entrepreneurs’ actions are impacted by current values and goals held in different sociocultural contexts (Silva et al., 2014). Entrepreneurs’ approaches based on more intrinsic motivations to a CE are expected to be particularly susceptible to the lack of sociocultural support, because they often contradict the overarching linear system (Ryan et al., 2008; Silva et al., 2014). Regarding different sociocultural contexts, the existing literature is highly focused on Western Europe, while other regions have received much less attention. Studying other contexts is crucial in helping to develop an appropriate understanding of the transition towards a CE, because motivations and related approaches are likely to differ based on the sociocultural context. Motivations and approaches to a CE should be studied in conjunction, because the prior are a crucial prerequisite for the latter, as SDT argues (e.g., Gagné & Deci, 2005). Based on the above, this study poses two research questions emerging from the literature:

RQs: What motivates entrepreneurs to implement CE practices? How do their approaches to CE practices differ based on their sociocultural context?

Studying the first research question should help broaden the current perspectives of the CE literature that are highly focused on instrumental logic (Corvellec et al., 2021; Ghisellini et al., 2016). A more comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurs’ motivations towards a CE can allow the inclusion of more sustainability-focused approaches (see Corvellec et al., 2021) to the evidence base. Further, the second research question should produce evidence that considers the concrete application of a CE by forerunner entrepreneurs, which is expected to increase understanding of how the required change towards a CE (Kirchherr et al., 2017) could be achieved in different contexts around the globe. To this end, this qualitative empirical study utilised self-determination theory (SDT) to scrutinise the motivations and approaches to CE practices in the contexts of Finland and Japan. These two national contexts were selected due to both being among the few forerunner countries of CE (Ghisellini et al., 2016), their rather similar regulatory environments that encourage CE practices and their sociocultural environments being clearly distinct from each other.

Theoretical Background

Circular Economy

The CE is viewed as an implementation of sustainability (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Sustainability is seen as an umbrella term, while the CE’s aims and practical implementation are more tightly defined (Murray et al., 2017). The CE is gaining momentum among different sustainability concepts due to its practical potential towards systemic environmental sustainability (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017), making it a highly relevant concept for examination within the extensive topic of sustainability research (Dossa & Kaeufer, 2014; Mori et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2017; Pedersen et al., 2018; Russo & Tencati, 2009). The goals of sustainability are open-ended, and its responsibilities are diffused. However, the CE aims to move away from a linear economy by creating a closed-loop system through the efforts of businesses and regulators (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017).

The core practices of the CE are framed as reduce, reuse, recycle and recover (4R), and they are meant to be implemented through a systemic approach (Kirchherr et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2017). Reduce (e.g., design for long life, using what one already owns) and reuse (repair and refurbishing) aim to slow the cycle of production and consumption (Bocken et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2017). Recycling (processing used materials into new resources) closes the loop. Recovery (incineration for energy) is the last resort when materials can no longer be recycled. Optimally, in a CE, resources would circulate in the system without anything being purely “new” (Moosmayer et al., 2020). The CE contrasts the linear economy by aiming to redesign the underlying economic system of production and consumption.

Despite the sustainable premise of the CE concept, the existing literature tends to view the CE through an instrumental view, as a tool for economic prosperity (Kirchherr et al., 2017; Montabon et al., 2016), forgetting social sustainability and simplifying the environmental consequences (Corvellec et al., 2021; Geissendoerfer et al., 2017). Instrumental logic does not lead to systemic change; instead, it allows us to continue operating within the unsustainable linear system with some CE extensions that do not generate significant change. This logic also often prioritises recycling because the barriers to implementing it are lower than those of reducing and reusing, as these require vaster reconfigurations to the underlying business logic (Ghisellini et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2017). CE approaches based on the instrumental logic are lacking an ethical dimension (Murray et al., 2017). Instrumental logic makes the contributions of the CE to sustainability unclear and calls for questioning the way the CE is currently interpreted and put into practice (Corvellec et al., 2021).

This study considers CE to be inherently ethical and views CE through an ecologically dominant logic (EDL). In this logic, the natural environment is the basis for all social and economic action, and the social environment is a prerequisite for economic action (Griggs et al., 2013; Montabon et al., 2016). Thus, EDL ties the CE closely with sustainable development by prioritising environmental and social aspects over the economy, directing the CE narrative towards a more ethical direction. As an improvement to instrumental logic, integrative logic emphasises the mutual benefit of environmental, social and economic sustainability, as suggested by Gao and Bansal (2013). Even integrative logic has a pitfall with environmental and social responsibility as they are often viewed as an opportunity to accumulate profit (Montabon et al., 2016). EDL can be considered essential in a CE, as it connects the CE to its underlying aim of sustainability, while in contrast, instrumental logic creates separation between the two concepts. EDL does not overlook the economic aspect, but it considers economic viability after environmental and social aspects have been assessed (Montabon et al., 2016). Accordingly, EDL views the CE as an end in itself (instead of as a means for something else); inherently, it considers participation in the CE as ethical behaviour. To move away from instrumental logic, the question is how to become circular, instead of how to benefit from the CE (Gao & Bansal, 2013; Montabon et al., 2016).

One of the key enablers of a CE transition is novel circular businesses (Brennan et al., 2015; MacArthur, 2013). Entrepreneurial CE companies showcase a broad and encompassing CE (Rovanto & Bask, 2021) that can eventually shift the general informal rules of a society (Dacin et al., 2002; Levänen et al., 2018). Thus, entrepreneurs of CE companies are in a key position to contribute to a societal transition towards a CE. As a part of the systemic shift towards a CE, entrepreneurs’ motivations and approaches to implementing CE practices are central. Following EDL, this paper is particularly interested in entrepreneurs’ motivations that go beyond the instrumental view of the CE, towards more intertwined intrinsic and transcendent motivations. Such entrepreneurs can be viewed as being inherently motivated by the ethical aspects of sustainability and operating their businesses more closely aligned with EDL. To reach a fundamental shift towards a CE, this paper argues that we need to investigate entrepreneurs’ motivations to implement CE practices and their approaches, which are expected to be shaped by the sociocultural environment in which the companies operate.

Self-Determination Theory and Motivations

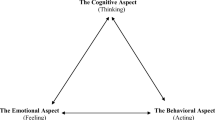

Self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1991) explains human motivations (Deci & Ryan, 2000) for engaging in various activities (van Schie et al., 2019) in different sociocultural contexts (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Entrepreneurs that operate a CE based on an instrumental logic can be assumed to have mostly extrinsic motivations to it, while EDL might require intrinsic motivations (see Fig. 1 for an illustration of the links between views on a CE and SDT). Other motivation theories (e.g., MacInnis et al., 1991; Schwartz, 1992) were considered for this study, but SDT was chosen as it was believed to best suit exploring the connection between the entrepreneurs’ type of motivation and their applied logic in operating a CE. SDT enabled an analysis of motivations based on their level of internalisation while taking the influence of the sociocultural context into account.

Self-Determination Continuum and Motivations

The self-determination theory makes a distinction between autonomous (intrinsic regulation) through controlled motivation (external regulation) (Gagné & Deci, 2005) (see Fig. 1 for the SDT continuum). Transcendent motivation, which refers to a genuine interest in other persons’ needs, can be considered as a further addition to the concept (Melé et al., 2019; Rosanas, 2008). The self-determination continuum can be particularly useful, as the current body of knowledge on the CE is mostly limited to examining drivers of linear economy companies in adopting CE elements (Agyemang et al., 2019; Govindan & Hasanagic, 2018; Levänen et al., 2018; Ranta et al., 2018), thus, in applying either a linear logic or an instrumental logic of the CE. The continuum can allow a systematic analysis of entrepreneurs’ motivations with different levels of internalisation, including the EDL perspective of CE discussions that currently focus mostly on an instrumental logic view of CE.

Internal motivations fall within intrinsic regulation; they prototypically emerge out of one’s interests (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Gagné & Deci, 2005), such as curiosity, a sense of challenge (Ryan, 1993) or enjoyment of carrying out an activity (Amabile, 1993). For long-lasting effectiveness, motives other than extrinsic ones are regarded as necessary (Rosanas, 2008). Ecologically dominant logic requires entrepreneurs to have such motivations to implement CE practices. For instance, an entrepreneur could be concerned about declining biodiversity and thus implement CE practices in their business of their own volition. Extrinsic motivation is based on regulatory behaviours that can be divided into four categories based on the level of internalisation: external, introjected, identified and integrated (Deci & Ryan, 2000). A lack of intent towards an activity represents amotivation. Extrinsically motivated actions are performed only because they are instrumental for achieving a desired outcome or avoiding an unpleasant one (Gagne and Deci, 2005). For example, an entrepreneur might implement CE elements only because legislation requires it.

Some level of internalisation is involved in three types of extrinsic regulation (Gagne and Deci, 2005): introjected, identified and integrated regulation. Introjected regulation refers to motivations that are not adopted by a person but rather are regulated by them; for instance, engaging in the CE for reputation benefit as a sustainable actor (Deci et al., 1994). Through identified regulation, a person accepts the value behind a behaviour more as their own, which typically leads to higher commitment and performance (Deci & Ryan, 2000). As an example, recycled materials are utilised to ensure a future supply for the continuity of the business. Integrated regulation refers to truly autonomous motivations (Gagné & Deci, 2005) that are integrated within one’s self (Deci & Ryan, 1991), even though these motivations did not emerge from within the individual. Both internal and integrated motivations are self-determined (Gagné & Deci, 2005).

Transcendent motivation indicates genuine interest in other persons’ needs beyond rational effectiveness in “doing good” and consideration of those that are impacted by one’s actions (Melé et al., 2019; Rosanas, 2008). As transcendent motivation is based on one’s interests (Melé et al., 2019), it is intrinsically regulated like intrinsic motivation. Transcendent motivation further integrates the topic of ethics into the discussion of motivations in general (Rosanas, 2008). Moreover, in a CE context, intrinsic and transcendent motivations overlap. Intrinsic interest in the CE concept includes by definition transcendent motivation: intrinsic motivation to CE practices includes “doing good” for the planet and for people. As environmental sustainability is considered a prerequisite for human well-being, intrinsic motivation to a CE can be argued to align with transcendent motivation. Accordingly, the analysis of intrinsic motivations covers ethical considerations of entrepreneurs to engage with CE. For simplicity, the paper uses the term intrinsic motivation to refer to intrinsic/transcendent motivations, while the term transcendent motivation is reserved for emphasising nuances in these motivations.

Three Basic Needs and Motivations Within Sociocultural Contexts

SDT argues that to be a self-determined person, three basic psychological needs must be satisfied. These basic needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness play a key role in the transmission, normalisation and maintenance of cultural elements in societies (Inghilleri, 1999). Autonomy refers to volition: a feeling of being in control of one’s own actions. Competence means being able to influence one’s environment and reach valued outcomes within it (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2000). Relatedness refers to a feeling of mutual respect and being socially integrated (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). People are more likely to pursue goals and relationships that support satisfying these basic needs (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

It is essential to understand how sociocultural contexts impact motivations through supporting or restricting these three basic needs (Ryan et al., 2008; Silva et al., 2014) and affect the ways in which the basic needs are experienced (Dacin et al., 2002). The internalisation of extrinsic motivations is impacted by the sociocultural context; people tend to internalise values in their social surroundings (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In collectivistic cultures, internalised cultural values may lead individuals to experience higher autonomy and relatedness through engaging in group norms, while conforming to group norms may threaten autonomy in more individualistic cultures (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Similarly, in an individualistic context, autonomy and competence may be best supported through individual decision-making, but in a collectivistic culture, by a trusted decision-maker within a group (Iyengar & Lepper, 1999). Intrinsic motivations are more likely to flourish in contexts with a sense of secure relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2000). A secure sense of relatedness is considered central in the internalisation of motivation alongside autonomy and competence (Ryan et al., 2008). For internalisation to occur, individuals need to freely explore their values and adjust them when necessary; external control, pressure and evaluations hamper rather than facilitate internalisation (Grolnick & Ryan, 1989; Williams & Deci, 1996). Fostering choice enhances the feeling of competence, whereas, for example, rewards hamper it, and feedback influences it (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

When people experience reasonable satisfaction of their basic needs, they do not particularly act to satisfy their needs; instead, they act based on what is interesting or important for them (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Internalised regulation is associated with more effective performance and greater behavioural persistence (Hayamizu, 1997; Ryan et al., 1993). For example, individuals with an intrinsic motivation for environmental protection are likely to further explore related matters and behave in a way that supports environmental protection (Seguin et al., 1998). It has been suggested that autonomous behaviour is particularly important when persistence and greater effort are needed for socially valued actions, which indicates a strong connection between self-determined motivation and environmentally protective action (Green-Demers et al., 1997).

The analysis of motivations needs to be extended, because autonomy, competence and relatedness are experienced differently depending on the context. Thus, it is essential to also analyse how the sociocultural environment influences the entrepreneurs’ approaches to CE practices. For instance, in an individualistic culture, such as Finland (Hofstede, 2001), direct activism based on intrinsic motivation for environmental protection might be a valid method, whereas in a more collectivistic culture, such as Japan (Hofstede, 2001), such direct action might not be viewed positively due to the importance of conforming to group norms. Thus, Finland and Japan provide an excellent comparison for exploring entrepreneurs’ motivations for the CE in different sociocultural environments.

Research Setting and Method

The study employed an interpretive inductive case study approach in which the overall aim was to maintain flexibility in order to detect novel relationships among constructs but at the same time allow a systematic analysis (Ciulli et al., 2020; Gehman et al., 2018; Gioia et al., 2013). The empirical study focused on entrepreneurs’ motivations and related approaches to CE practices in two countries with similar regulative but distinct sociocultural environments (Hofstede, 2001) through analysing data from eight companies in Finland and eight in Japan.

Context and Sampling

Sociocultural Contexts: Finland and Japan

The study aimed to understand the influence of sociocultural environment in addition to entrepreneurs’ motivations and approaches to CE. Thus, two contexts were sought for comparison; it was desirable for them to have clearly different sociocultural but similar regulatory environments in relation to the CE. Finland and Japan were identified as fulfilling these criteria in an exemplary manner (see Table 1 for the core differences and similarities between Finland and Japan; Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010) and were seen as ideal sociocultural contexts for the study. As an EU member state, Finland is subject to the European Commission (2015) CE plan. Moreover, in 2018, the environmental ministries in these two countries signed a memorandum of environmental cooperation as a commitment to work together in promoting sustainable development, including a CE (Laita, 2018). In addition, the focus on Japan is expected to provide novel perspectives to the CE discussion that has been rather focused on Western Europe. Indeed, some nascent concepts (Gioia et al., 2013) were found in Japan that did not seem to have adequate theoretical referents in the existing literature (see Sects. Masked CE Approach and Adherence to the Linear System).

Industry Context: CE in the Clothing and Textile Industry

The clothing and textile sector serves well as an industry context due to its negative environmental impact and corresponding efforts to find circular solutions. The industry is characterised by an extensive use of resources, short product lifecycles, over-consumption, excessive water use, toxic chemicals and waste (Pedersen et al., 2018). The social burden of the industry includes child labour, low wages and occupational health issues (Allwood et al., 2006). The end products of the clothing industry are nowadays only worn seven times on average (Thomas, 2019) and designed to last only ten washing cycles (McAfee et al., 2004). To tackle these global issues within the industry, several established companies have begun experimenting with CE innovations, and new CE businesses have started to emerge (Pedersen et al., 2018).

Sampling

The sampling first targeted companies to find real-life applications of CE practices. After having sampled the companies, the analysis focused on the entrepreneurs’ motivations and related approaches to CE practices. The systematic sampling of companies was conducted based on the following criteria derived from the literature (Patton, 1990):

-

Criterion 1a. Identifiable CE application. The sampled companies had to use the terms “circular economy”, “sustainability” or “sustainable” (Kirchherr et al., 2017) on their web pages or social media or describe their business with specific terminology related to the CE (such as “up-cycle” and “reform”).

-

Criterion 1b. Application of CE practices. The companies had to employ advanced strategies to reduce, reuse and/or recycle and recover (4R) in their operations (Bocken et al., 2016). Reduction and reuse could be carried out through extending product lives (e.g., design for durability and for ease of repair). Recycle and recover means directing post-use resources back to production (e.g., using post-consumer textiles in new products).

-

Criterion 2a. Sociocultural context. The companies had to be founded and mainly operating in either Finland or Japan (see Table 1 for a comparison of the core characteristics of these two sociocultural contexts; Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010).

-

Criterion 2b. Balanced samples in each sociocultural context. Companies from Finland and Japan were selected so that the samples from both countries consisted of companies with comparable basic characteristics (Gioia et al., 2013).

-

Criterion 3. Clothing and textiles industry context. The primary industry of each company had to be in clothing and textiles. Even though some companies had other types of businesses as well (such as accessories and cosmetics), the focus of the study was on their clothing and textiles businesses.

-

Criterion 4. Entrepreneurial focus. Each company had to have a strong entrepreneurial focus (Davidsson et al., 2006). Eleven of those were micro or small companies, and the remaining five fulfilled the criteria and were labelled in the following ways. Marketplace and GarmentRecycling were managed by the founder, while SecondHand 2 and DurableGarments were family-owned companies with descendants of the founders managing the companies. InteriorTextile began its CE implementation after a change of ownership; one of the new owners became the CEO and the face of sustainability actions of the company.

-

Criterion 5. Company access. Among the companies that fit the first four selection criteria, access to them (Patton, 1990) was the last criterion in the sampling because it was often difficult to arrange. Particularly in Japan, achieving access to companies requires persistent hard work and the utilisation of personal connections (see Bansal & Roth, 2000). Accordingly, the current empirical dataset from eight Japanese companies has particular value, as it may provide novel insights into CE discussions.

Data Collection

The primary empirical data consisted of 27 semi-structured interviews (Corley & Gioia, 2004; Gioia et al., 2013) that were conducted mainly with founders, CEOs and/or members of the entrepreneurs’ families. The interviews and a wealth of supporting data were collected from a total of 16 companies, which are summarised in Table 2. The interview protocol consisted of questions about entrepreneurs’ motivations, values and CE practices at their companies. The analysis was chosen to focus on the entrepreneurs as knowledgeable agents that run CE businesses (Gioia et al., 2013). This focus was expected to be particularly useful because CE entrepreneurs were assumed to “know quite well what they’re trying to accomplish, can explain to us researchers quite well what they are trying to do, how they are trying to do it [approaches to CE practices], and perhaps most importantly, why they are trying to do it [their motivations]” (Gioia, 2019, p. 31). Accordingly, the aim was to study entrepreneurs’ motivations for CE practices, related approaches in these practices and how these approaches were shaped by the sociocultural environment in which they operated.

Regarding entrepreneurs’ motivations and related approaches to CE practices, a single interviewee could be expected to provide reliable data, as (in small companies) it might be impossible to find others that were sufficiently knowledgeable (Holt et al., 2017). Further, including small and medium-sized enterprises in the research was essential to allow an entrepreneurial focus as well as to guard against a bias towards large firms in the field (Kull et al., 2018). Considering single respondents, the interviewees (most often founders) were in key positions to provide information (Lyon et al., 2000). Typically, a significant amount of other data to support the interviewee’s message were made available (see Table 2 for the supporting data). As the sampling was not focused on company size, a large company, Marketplace, was also included in the study as a core example of the implementation of CE practices in Japan. Marketplace is an entrepreneurial company in which the founder-entrepreneur still runs the company as the CEO. In three case companies (InteriorTextile, RecycledFibre and Marketplace), other representatives deeply informed about the CE practices at their companies were interviewed (see Table 2). In these cases, the interview information was supplemented with rich data from other sources regarding the companies’ operations and the entrepreneurs’ motivations.

A flexible semi-structured interview approach was used to obtain data on key questions, which also left room for the important task of concept development through following wherever the interviewees led the discussion regarding the investigation of motivations and approaches (Gioia et al., 2013). All the interviews were conducted by the first author, who was fluent in Finnish and qualified in Japanese and English (Ciulli et al., 2020). The interviews were recorded, transcribed and translated into English, and each interviewee was given a chance to review the accuracy of the information on the transcript (Gioia et al., 2013). When possible, the validity of the interview information was enhanced by triangulating it with data collected from other sources (see Table 2).

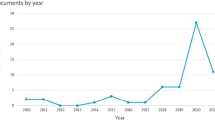

Analytical Procedure, Validity and Reliability

The primary and secondary data were analysed in an inductive manner (Gioia, 2019; Gioia et al., 2013) through iterative coding (Saldaña, 2015, p. 368) and the categorisation of data (Grodal et al., 2020). Essentially, the analysis included the following three stages (see Fig. 2 for data structure): (1) informant-centric codes, taking notes of any relevant observations that were considered to reflect the data well; (2) theory-centric themes, highlighting the core elements of the initial categories through collapsing these concepts into themes; and (3) theoretical dimensions, forming novel theoretical insights by aggregating the themes (Gioia et al., 2013; Patvardhan et al., 2015). One of the authors of the paper adopted an outsider view to distance themselves from the empirical data, with the aim “to critique interpretations that might look a little too gullible” (Gioia et al., 2013, p. 19). This proved useful in the data analysis phase, where continuous intensive discussions within the author team pushed the analysis forward, towards presenting the data in a more structured manner and refining the initial theoretical insights.

Data structure of findings on CE entrepreneurs’ motivations (method based on Corley & Gioia, 2004)

In the first stage, the study aimed to identify emerging themes with terminology as close as possible to what was used by the interviewee (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Secondary data were analysed for the same themes identified in the interview data and for other significant themes. Once a strong set of themes was identified, relevant passages in the raw data were revisited to review whether the themes complied with the data. For instance, the analysis identified that a concept formed from a cluster of codes, such as “appreciate something that happened before” and “transferring what our ancestors created to future generations”. These codes were grouped into the theme “Appreciating things created in the past”. With this process, similarities and differences, as well as patterns within and across sociocultural contexts, were sought (Gioia et al., 2013).

The identified themes were then examined through the lens of SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000). The entrepreneurs’ motivations for CE practices were further divided into groups based on their level of internalisation. Intrinsic and integrated motivations were grouped together due to their internal nature (Sect. Intrinsic and Integrated Motivation). Introjected and identified motivations were also grouped together (Sect. Identified and Introjected Motivation), while external motivations and amotivations formed the third group with most extrinsic motivations (Sect. External Motivation and Amotivation) (see Fig. 1). The approaches to CE practices were divided into three groups (see Sect. Approaches to CE Practices). The impact of sociocultural context was examined from the perspective of how the entrepreneurs’ basic needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness were fulfilled in the two countries that were studied. The data were visited iteratively (Gioia et al., 2013), and when new significant findings no longer emerged, the analysis concluded that theoretical saturation had occurred (Patvardhan et al., 2015). Data collection was then discontinued, and the data analysis proceeded to aggregate the theoretical dimensions. This aggregation was based on abductive reasoning (Gioia et al., 2013; Mantere & Ketokivi, 2013), which involved iterations among the empirical data, analysis and theories. Based on this analysis, a data coding structure was built (see Fig. 2).

The study established reliability primarily through using the protocol of Gioia et al. (2013) and by creating a case study database (Yin, 2009). Construct validity was achieved through utilising multiple sources of evidence (including, for instance, interviews as primary data and company documents, websites and emails as secondary data when possible) and aligning this data with the existing literature. The chain of evidence, from the interview questions and objectives of the study, through the database and coding, to the reporting of the findings, was also established. Internal validity was considered in the study by pattern matching among the quotes, codes and the existing literature. This led to the formation of themes and generalisations across the data. External validity meant in practice transferability (Gioia et al., 2013), which was strengthened by using existing self-determination theory to achieve transferable results.

Findings

This section first presents the findings on the motivations of entrepreneurs in Finland (FI) and Japan (JP) and proceeds to analyse their approaches related to CE practices. Even though the contrasts between the two countries were not black and white, there were evident differences in the types of motivations and approaches of the entrepreneurs depending on the sociocultural context.

Motivations of Entrepreneurs in CE Practices

The findings on the motivations of entrepreneurs in implementing CE practices are presented next and summarised in Table 3. The companies in Table 3 are organised by country based on the following logic: entrepreneur’s type of motivation, the type of action and their order of occurrence in the text. The findings on the motivations were structured into three categories based on their level of internalisation: (1) intrinsic and integrated, including transcendent (see Sect. Intrinsic and Integrated Motivation); (2) identified and introjected (Sect. Identified and Introjected Motivation) and (3) external and amotivation (Sect. External Motivation and Amotivation). The analysis considered only the motivation of CE practices; the entrepreneurs might have also had other motivations for founding and operating their companies. The motivations presented in the following sections were not mutually exclusive, as entrepreneurs often had several motivations related to CE practices.

Intrinsic and Integrated Motivation

Intrinsic and integrated motivations for CE practices were identified as falling into three themes: (1) contributing towards solving an environmental (and social) issue, (2) provoking change towards the CE in the linear economy system, and (3) expressing appreciation towards what has been created in the past (for a synthesis of main findings, see Fig. 3 at the very of Sect. Findings).

First, the motivation of all the entrepreneurs to implement CE practices, except for three of the Japanese companies, was based on being interested in contributing towards solving environmental issues, while also social issues were addressed by some (five Finnish and two Japanese companies). Although most of the studied entrepreneurs had intrinsic motivation to implement CE practices, some having been longer in business expressed similar but more integrated motivations (FI: InteriorTextile, DurableGarments; JP: SecondHand 2). These companies had operated according to the linear economy and, at some point, realised the importance of the CE. Interestingly, although SecondHand 2 implemented its CE business without having a sustainability ideology (second-hand items were less expensive than new ones), the company leaders have since experienced an internalisation of motivations towards CE practices. While the FibreInnovation entrepreneur’s motivation to develop a new fibre innovation could be seen as mainly intrinsic, their motivation towards the CE also carried transcendent aspects, as they were interested in contributing towards sustainability through their innovation. In general, these entrepreneurs sought to contribute to solving sustainability-related issues, as illustrated in the following:

“When I was very young, I […] stopped buying new things. It was a consumption choice for me already before founding the company.” (The founder of SecondHand 1)

“I was shocked [by the state of] old clothes disposal, […] more than 90% of the old clothes, textiles, [were] discarded for landfill or insulation. I wanted to solve this problem.” (A founder of GarmentRecycling)

“There was no product or service, but there was a thought and an ideology of how this world should be … things cannot continue as they are”. (The entrepreneur of SustainableDesign)

“From the start, I wanted to help create a society in which things are used with care.” (The founder of Marketplace in the company’s blog)

“Achieving a huge economic success isn’t the goal, neither is it guiding the way. Our thoughts and actions form the business”. (The founder of CircularBags)

Second, intrinsic motivation based on provoking change in production and consumption habits in society was present at many of the companies as well (four Finnish; three Japanese). These companies aimed to change “the society’s way of thinking”, as the founder of ScrapMaterialTShirts put it, with long-term sustainability in mind. These entrepreneurs were worried about the prevailing consumption culture and had intrinsic motivation to contribute to a positive change for environmental sustainability through implementing CE practices:

“I had a strong personal feeling that the resources that were thrown away shouldn’t be thrown away […] At the same time, there’s a big problem against the mass production consumer society, I thought it would be necessary to signpost this change… Until now, the economy and society have been the top priorities. But from now on, I think, it’s necessary to look at the development from environmental and cultural standpoints.” (The founder of CircularBags)

Third, some intrinsic motivations for CE practices emerged from an interest in preservation of historical value and/or nostalgia (FI: SecondHand 1; JP: CircularBags). The founder of SecondHand 1 identified themself as always having been a “nostalgic” person who was incredibly interested in “past times, decades, centuries” and that their interest in sustainability sprung from this foundation. The founder also mentioned that they did not see the value of current mass-produced fast fashion; the hunt for unique vintage items was an important motivator for them. The interests in history of the entrepreneurs of CircularBags and SecondHand 1 were tightly connected to their interest in sustainability. CircularBags’ founder directly connected respect for the past to sustainability:

“[R]especting what our ancestors have built, taking it to our children, future generations”. (The founder of CircularBags)

Intrinsic motivation to CE practices typically emerges from interests primarily connected to environmental sustainability. However, as the above findings show, the idea of sustaining what past generations have created can also be an important intrinsic motivation for entrepreneurs.

Identified and Introjected Motivation

The identified motivation for CE practices was observed to be based on matters within the themes of (1) the availability and low price of second-hand materials, (2) culture and cultural change and (3) long-term economic well-being. Introjected motivation was not clearly present in the sample, perhaps due to quite an advanced nature of CE applications within the companies in comparison to their peers. The identified motivations in some companies were the primary reasons for CE practices, and sometimes they accompanied other motivations.

First, the motivation for CE implementation of three Japanese companies was based on utilising second-hand resources for lower cost and/or better availability. Interestingly, this identified motivation for CE practices was disconnected from any interest in CE and sustainability concepts. For instance, the founder of SecondHand 3 described originally having gone to Scandinavia to source Nordic fashion for a clothing shop they wanted to establish. However, due to the high prices of new products, they decided to opt for vintage items, as did SecondHand 2. KimonoReform 2 operated a tailor shop before focusing on kimono reform. The switch to CE operations was just a way to make a living for the entrepreneur’s family. At the time of the study, these three companies had operated in the CE for over a decade, considerably longer than the studied companies whose entrepreneurs had intrinsic motivation for CE practices. Some of their motivations are illustrated in the following examples:

“First, ten, fifteen years [note: the company was founded in 1966], we were selling only new [items]. [Then,] we have more competition, bigger stores, chain stores, so we cannot survive. Then [the founder of the company] decided to [start] selling used clothing”. (CEO of SecondHand 2)

“When we have more [possibilities] for the business, then [it is] good for the environment [...] But honestly, more than 70% is for the business. But not only for the business, I hope”. (CEO of SecondHand 2)

Second, customer demand for the CE business of KimonoReform 2 was based on a cultural change. Kimonos are traditionally passed on to the next generation; however, the present generations do not often wear kimonos as in the past. The entrepreneur’s family described how they have gained expertise with reforming kimonos into modern wear and learnt about kimonos from their customers during the past 20 years. They perceived these unused, unwanted, valuable, and high-quality kimonos as “sleeping” and kept in drawers as people just did not want to throw them away. By upcycling kimonos into new garments, people could wear the traditional kimono as everyday clothing in a new form.

Third, primarily Finnish companies (FI: InteriorTextile, DurableGarments) implemented CE practices to gain (long-term) economic benefit. The informants at the two Finnish companies emphasised risk control to enhance long-term economic sustainability. Interestingly, the companies in this group followed instrumental logic towards a CE to ensure the future well-being of their businesses. These companies also had motivations based on solving environmental issues, as described in the previous section. The sustainability discourse has also been spreading in Finnish society:

“We generated a very healthy profit last year and grew a lot […] at the same time we have been carrying out sustainability work […] They feed each other. [The CE] brings added value”. (The sustainability manager of InteriorTextile)

Identified motivations for CE practices were found to be relatively common. They can emerge from various sources within the linear system or due to reasons connected to the sustainability paradigm.

External Motivation and Amotivation

No entrepreneurs in the study exhibited external motivation or amotivation towards CE practices. The lack of external motivation might be due to the rather advanced CE application at the companies and the lack of direct legal enforcement towards the CE. Amotivation to CE practices was likely not identified due to the study’s sampling criterion for advanced strategies to reduce, reuse, recycle and recover (see Sect. Context and sampling). However, surprisingly, entrepreneurs in three Japanese companies (KimonoReform 1, SecondHand 3, KimonoReform 2) showed amotivation to the CE concept despite having implemented CE practices in their businesses. The SecondHand 2 entrepreneur’s father, the founder of the company, initially had no interest in sustainability but rather adopted a second-hand practice to stay in business, and the entrepreneur gained interest in CE later on. The entrepreneurs at SecondHand 3 and KimonoReform 2 had not been aware of the CE at the time of implementation and continued to lack motivations towards it, and KimonoReform 1 explicitly expressed a lack of interest in the concept:

“I do not really want to use these kinds of words, ecology. Because this is not about ecology.” (The founder of KimonoReform 1)

The KimonoReform 1 and SecondHand 3 entrepreneurs directly stated that they did not have interest in the CE as a concept. The daughter of the KimonoReform 2 founder illustratively described the intersection of the kimono upcycling business and heightened societal awareness of sustainability as a “fortunate coincidence”. The KimonoReform 2 and SecondHand 3 entrepreneurs expressed that they also lacked any interest in contributing on the environmental side, although both had become aware of the environmental contributions of their businesses.

These companies possessed other types of motivations for implementing CE practice than those emerging from the CE and sustainability discourse. While SecondHand 3 and KimonoReform 2 had identified motivation towards the CE (Sect. Identified and introjected motivation), the entrepreneur of KimonoReform 1 was passionate about their native culture and described themselves as “an ‘old soul’ with a deep appreciation for history and culture”. This motivation emerged from a similar source as the intrinsic motivation of appreciating things created in the past, but we do not regard it as intrinsic motivation to a CE, as the entrepreneurs explicitly lacked interest in the concept:

“I do not [do] recycling; I like repurposing something”. (The founder of KimonoReform 1)

Thus, without the entrepreneur being particularly interested in sustainability or CE concepts, a company can implement CE practices, and it can learn about sustainability through experience. Overall, in Finland, motivations were highly intrinsic/integrated, while Japan exhibited a fragmentation of motivations.

Approaches to CE Practice

This section presents findings on the entrepreneurs’ approaches to CE practices, which are shaped by the sociocultural environment. Entrepreneurs with internal and integrated motivations were identified as taking an explicit CE approach in Finland (Sect. Explicit CE Approach) and a masked CE approach in Japan (Sect. Masked CE approach). Entrepreneurs with more external motivations and amotivation to the CE concept tended to adhere to the linear system in both countries (Sect. Adherence to the Linear System). Figure 3 is presented at the very end of Sect. Findings, and it synthesises the main empirical findings.

The main overall differences between the sociocultural environments of Finland (FI) and Japan (JP) were perhaps best illustrated through the examples of SustainableDesign (FI) and GarmentRecycling (JP). The entrepreneurs perceived that Finnish society had taken significant steps towards CE becoming a norm, while sustainability was not considered particularly intriguing in Japanese society:

“…[R]esponsible design is not a dim star in the sky but the new design standard. […] Responsibility has become a part of the mainstream.” (SustainableDesign press release, 15 September 2018)

“[E]nvironmental protection is […] not so interesting for some people […] We need add-ons, add some fun or joy […], feeling, emotion, to our sustainable actions.” (A founder of GarmentRecycling)

Explicit CE Approach

In Finland, all the studied entrepreneurs seemed to have reached sufficient fulfilment of the three basic needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) through their CE businesses. The entrepreneurs did not actively need to seek the fulfilment of their basic need for autonomy, but they could independently and openly act based on their CE-related interests in the individualistic Finnish society. The entrepreneurs were able to relate to the surrounding sustainability community and be vocal about their CE approaches. The Finnish climate had become positive enough towards the CE that the SustainableDesign founder did not feel the need to push for sustainable values as before, because they were already internalised in the society to some extent. The existence and visibility of peers in Finland fostered the CE entrepreneurs’ feelings of relatedness, as it was relatively easy to find other entrepreneurs with shared values:

“In Finland, there’s quite a good bustle going on. There are a lot of companies which do work on social or environmental responsibility and which look at it from a circular economy point of view.” (The representative from RecycledFibre)

The widespread presence of the CE in society supported the feeling of relatedness of the CE entrepreneurs. Thus, through establishing CE businesses based on the entrepreneurs’ intrinsic and transcendent motivations, the entrepreneurs also laid the foundation for their peers to feel a secure sense of relatedness. Perhaps, such a local CE community had been able to emerge in Finland due to sustainable values aligning with the feminine dimension (preference for caring, cooperation and quality of life) of the Finnish culture (see Table 1 in Sect. Context and sampling). Further support for relatedness came from the consumers in Finland who seemed to understand and even be ready to pay for the value of the CE:

“Our Jesus sheets […] are a common-looking linen sheet set, but they have a story, a 50-year guarantee and the price is triple our normal sheets. [...] We have sold a lot of them. [...] In my opinion, this is a very strong message that there is demand for more sustainable products.” (The sustainability manager of InteriorTextile)

Many of the Finnish companies were acknowledged by different actors as experts on the CE, which created a strong feeling of competence. This was a result of the companies having been established as sustainability pioneers in the country and having routinised their CE operations through years of work on a CE. As an example of the recognition of this competence, SustainableDesign, CircularWorkwear, RecycledFibre, FibreInnovation, ClothingLibrary, InteriorTextiles and DurableGarments have been invited as experts to participate in CE initiatives and/or have been cited as CE examples in publications of organisations driving the CE forward in Finland. Low power distance in Finland could be seen as a factor that enables the recognition of such expertise at a grassroots level.

The widespread presence of intrinsic/integrated motivation among CE entrepreneurs and a sociocultural environment that increasingly values CE supported each other. The more entrepreneurs had been vocal about their motivation to implement CE practices, the more the CE had become the social norm and vice versa. The sociocultural environment seemed to foster autonomy, competence and relatedness of CE entrepreneurs, making it a relatively easy ground for their intrinsic motivations to flourish and external motivations to become internalised, which likely explains the widespread presence of intrinsic/integrated motivations among the studied Finnish entrepreneurs. Perhaps the individualistic Finnish culture that fostered autonomous action without high pressure to conform to societal norms had enabled making a rather radical and open push towards a CE and taking a big step towards a CE away from the dominating linear logic.

The CE had been institutionalised in Finland to a degree that entrepreneurs were able to successfully seek sociocultural support for their interests in it. This was despite linear logic still being largely dominant within society. For example, InteriorTextile saw this ignorance of sustainability as their biggest “competitor” instead of other companies:

“Companies making products that are competing with those of ours so to say, we used to consider them as our competitors. But actually, our only competitor is the ignorance of people.” (The owner-CEO of InteriorTextile in a TV interview)

To summarise, CE operations were welcomed in Finnish society, while entrepreneurs possessed an important role in the possible further sociocultural institutionalisation of the CE. It seems that entrepreneurs’ intrinsic/integrated motivations to implement CE practices together with support from peer companies that have openly implemented CE practices and a general interest in the CE within the society have created a virtuous cycle.

Masked CE Approach

In Japan, entrepreneurs with intrinsic/integrated motivation in CE practices have struggled to find support for the three basic needs. Accordingly, they have used various creative ways to try to do this. The entrepreneurs in Japan sought to fulfil their sense of autonomy by consistent action based on their own interests in the CE, for example, by simply continuing to produce and sell items made from recycled materials. They felt that pressures to conform restricted their attempt for autonomy, because their CE motivations contradicted the social norms of the linear-dominated sociocultural environment:

“[In Japan,] they don’t want to […] do something which they’ve never done. It’s like they don’t have the guts to try something innovative that no one has never done.” (The entrepreneur of KimonoReform 1)

“[M]ost of the Japanese companies have a kind of traditional Japanese culture; [don’t] challenge and just obey the traditional way. But we are trying something new […] So we don’t care about the traditional way [...] or what people say […] This is very unique”. (The representative from Marketplace)

CE entrepreneurs with intrinsic/integrated motivation for CE practices often sought to find ways to relate with Japanese customers who were not particularly interested in the CE. The entrepreneurs reported that a large portion of their customers preferred aspects other than sustainability, such as the unique style of the products or a lower price, or as the CEO of SecondHand 2 describes: “[I]f they like it, they buy [it]. That’s all.” CircularBags aimed to foster relatedness with the consumers by designing products so that any customers interested in the CE noticed that they were made from second-hand materials, but customers preferring style did not necessarily become aware of their CE aspects at all. GarmentRecycling’s operations have also become more visible in the form of collection boxes in shops for recycling clothes. Notably, this has happened through their larger business-to-business customers, who were likely influenced by international pressures towards sustainability rather than by the local sociocultural context. Moreover, entrepreneurs particularly interested in provoking change towards the CE opted to hide their attempts at change to maintain a feeling of relatedness, instead of more openly going against the mainstream. Japanese entrepreneurs pursued relatedness with consumers through masking their CE approach by making it fun:

“[The] focus on environment protection is so [serious]. […] We need add-ons, add some fun or joy”. (A founder of GarmentRecycling)

“[We provide] an exciting and fun experience that comes about naturally, helping to realise a […] circular economy…” (Sustainability in Marketplace presentation)

While Marketplace also conducted educational activities about sustainability, their main path in seeking relatedness with consumers was not through highlighting sustainability. GarmentRecycling described that “customers like a story” behind a sustainable CE product, despite lacking interest in sustainability. For instance, the company had a collaboration that incorporated the waste-fuelled car from the Back to the Future movies, somewhat masking their CE approach. GarmentRecycling and Marketplace believed that customers did not need to be interested in the CE if they engaged in it for other reasons. Accordingly, through masking their CE approach, these entrepreneurs were able to gain a feeling of relatedness in their attempts to generate an impact on their social environment. Accordingly, these companies modestly challenged the prevailing linear system and expanded the CE from within the linear system. Reaching more customers for the CE through this masking approach was aimed at somewhat helping legitimise CE in the prevailing linear economy. For example, Marketplace users have become increasingly conscious about the resale value of their products, as previously sold listings can be viewed on their platform. This encourages the users towards improved product quality, better maintenance of their belongings and the ability to re-sell the items instead of disposing of them. However, the CE businesses still remained largely hidden from the mainstream.

In general, Japanese entrepreneurs with intrinsic/integrated motivation in CE practices reported finding support for the feeling of relatedness as particularly challenging. As a solution to this, the entrepreneurs found ways to relate with the prevailing linear system through masking their CE business. However, the masked approach further hindered other CE entrepreneurs in finding support from their peers with regard to their needs of relatedness. As a manifestation of this, when asked for prominent CE companies, Japanese interviewees only named foreign companies, if any. In the absence of a local sustainability community, the entrepreneur from CircularBags indicated having found relatedness in the international sustainability community. CircularBags also described some of its current customers as being largely Japanese divisions of international companies interested in the CE. In a collectivistic culture, such as Japan, social integration is important, and public disruption is typically not favoured, which further increases the need for relatedness. The entrepreneurs found some support for the feeling of competence from being able to navigate this challenging environment that was largely dominated by linear logic. However, the fulfilment of the need for relatedness could be seen as critical in a change towards a CE in a relatively collectivistic and very masculine Japanese society with high power distance.

To summarise, Japanese entrepreneurs with intrinsic/integrated motivation sought ways to mask their CE practices to better relate with their peers and consumers within the linear system. Interestingly, the Japanese culture did in fact provide some support for the underlying long-term orientation of a CE. SecondHand 2, Marketplace and KimonoReform 2 brought up the Japanese saying mottainai, which expresses regret over waste (see also Sato, 2017). Japan’s long-term-oriented culture creates an accepting environment to pass on cultural value, which indicates some support for the motivation of appreciating things created in the past. However, because of the lack of support for the three basic needs, this long-term orientation did not materialise in an overall flourishing of CE businesses in Japan but more of a CE stagnation.

Adherence to the Linear System

The analysis identified that two Finnish and four Japanese entrepreneurs relied largely on linear logic, despite operating (partially or fully) de facto 4R practices of the CE (for 4R, see Sect. Circular economy). Such operations were titled as ‘adherence to linear system’ and were identified among entrepreneurs that had more extrinsic motivations and amotivations towards the CE concept. The companies were established without any regard to the CE concept because the entrepreneurs were not aware of it. These entrepreneurs’ autonomous interests were largely based on operating a business through linear logic, where, for example, profitability and growth indicate competence. The entrepreneurs were easily able to find relatedness in the surrounding linear society without having to actively seek to fulfil this need. The entrepreneurs of the two countries operated slightly differently, even though they all adhered to the linear system.

In Finland, InteriorTextile and DurableGarments integrated CE elements into their linear businesses with the aim of making their businesses more circular. These entrepreneurs had twofold motivations towards CE practices: intrinsic/integrated (see Sect. Intrinsic and integrated motivation) and identified/introjected motivations (Sect. Identified and introjected motivation). Their basic needs were fulfilled in one part through an explicit CE approach (Sect. Explicit CE approach) and in the other part through adhering to the linear system. The entrepreneurs seemed to rely on instrumental logic to the CE, where they had viewed CE as a way to generate business benefits while “doing good”. For instance, InteriorTextile viewed CE adoption as a win–win: while launching products from recycled materials was good for the environment, it boosted the public image and economic returns of the company. Similarly, DurableGarments saw the adoption of CE practices as a means to control risks, because it was considered necessary for the continuity of the business in the future.

In Japan, entrepreneurs with extrinsic motivations and amotivations towards the CE concept operated their CE businesses through linear logics. This meant that these entrepreneurs had been unaware of the sustainable aspects of the practices that they implemented for reasons outside the circular view. KimonoReform 2 simply responded to customer demand through establishing their business, while SecondHand 3 chose to sell second-hand items due to lower sourcing costs compared to new items. The entrepreneur of SecondHand 2 developed intrinsic motivation towards CE practices later, but this happened after the CE business had already been established. Accordingly, these three companies operated based on a linear logic. Additionally, the KimonoReform 1 entrepreneur expressed interest in preserving cultural value and a lack of interest in the CE. However, they clearly adhered to the linear system. For instance, their supply chain decisions were made based on creating luxury items: finding the most skilled workers to sew the old kimonos into wearable pieces of art.

To summarise, two Finnish and four Japanese entrepreneurs with more extrinsic motivations and amotivations towards the CE concept were identified as adhering to the linear system but in slightly different ways. The Finnish entrepreneurs had originally adopted an instrumental logic to CE and operated linear businesses with some CE extensions. The Japanese entrepreneurs followed the linear logic and operated CE businesses through linear assumptions while being aware of the circularity and sustainability of their operations.

Discussion and Conclusions

Theoretical Contributions

This study aimed to expand the current understanding of entrepreneurs’ motivations to implement CE practices (Jia et al., 2020; Moktadir et al., 2018) and the effects of sociocultural environments on their approaches to these practices. The theoretical implications are three-fold.

First, the study shows that it is essential to go beyond instrumental (Corvellec et al., 2021; Kirchherr et al., 2017; Montabon et al., 2016) and integrative logics (Gao & Bansal, 2013) of a CE towards an ecologically dominant logic (EDL) to reach a more comprehensive understanding of ethical CE approaches at companies. Entrepreneurs that had intrinsic motivations and that implemented advanced CE practices do not view the CE through an instrumental logic as a means towards something else. Instead, they follow EDL in which intrinsic and transcendent motivations to CE tightly intertwine: ethical behaviour, “doing good”, is the reason why they engage with a CE. Essentially, transcendent values seem to be an inseparable part of advanced CE. CE approaches that align with EDL lead us towards a CE that is based on ethical, rather than economic values (Murray et al., 2017). Mere instrumental logic would overlook these entrepreneurs and hinder us from developing a more encompassing view that also covers the most advanced CE practices of companies. Economic incentives to carry out a CE (Govindan & Hasanagic, 2018) are only one type of entrepreneur motivation among many others and may often coexist with intrinsic and identified motivations.

Second, the study somewhat contradicts the SDT view on deeper interest in activities leading to better results of actions (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Seguin et al., 1998). This was done through the identification of four Japanese entrepreneurs that have operated a business highly based on CE practices, without any interest in the CE concept, sustainability or environmental protection at the time of establishing the CE business. These findings are not aligned with the dominant instrumental logic (Corvellec et al., 2021; Montabon et al., 2016), because the entrepreneurs did not view the CE as a means to generate business; rather, they did not have any interest whatsoever in the CE concept or sustainability. This is a significant addition to CE discussions (Ghisellini et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2017) that consider ways to carry out CE practices in contexts where individuals are not (yet) particularly interested in the CE or sustainability. Accordingly, CE may have a presence in unchartered businesses where even the entrepreneurs themselves have not realised their businesses may be based on the CE. This novel perspective also opens research avenues into industries, such as repair businesses, where there arguably will exist highly circular approaches without an intentional connection to the CE or sustainability due to their long-standing histories.

Third, the study identified how the sociocultural environment may shape the ways through which societies can change towards a CE (Ghisellini et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2017). Entrepreneurs’ motivations led to different types of approaches to a CE depending on the characteristics of their sociocultural environments; particularly, the need for relatedness seemed to have a significant role in this. The CE calls for a fundamental shift in the ways of production and consumption (Corvellec et al., 2021; Ghisellini et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2017), a change that might be better initially enabled by an individualistic rather than a collectivistic culture. Entrepreneurs with intrinsic/integrated motivations to a CE and having their three basic needs fulfilled are likely to be vocal about their CE approach, as in Finland. This supports other CE entrepreneurs’ needs for relatedness and creates a virtuous cycle where CE businesses become socially normalised. In contrast, when CE entrepreneurs with intrinsic/integrated motivations do not receive support for the three basic needs, they may take a masked CE approach, as in Japan. This could hinder other CE entrepreneurs from relating with their peers, preventing the CE from becoming socially normalised and somewhat stagnating the society’s possible move towards circularity. These characteristics emphasise the importance of entrepreneurs feeling socially connected to others in a society in which autonomous action is difficult. A more individualistic society (with low power distance) would support autonomous action towards a CE, thus creating relatedness to others that also support a change towards a CE.

In addition to collectivism, highly masculine characteristics (being the best, competitiveness, success, achievement) in a culture might be significant factors preventing a shift towards an ethical CE. While collectivism can make the shift towards a CE difficult, high masculinity can make internalization of transcendent motivations (Melé et al., 2019; Rosanas, 2008) towards a CE per se highly challenging. This can be particularly relevant in the context of an ethical CE that is aligned with EDL. Previous research has indicated that Japan has one of the world’s most masculine sociocultural contexts (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010) that is more focused on self-interest than those in a variety of other countries (Horioka, 2021). As a CE aligned with EDL calls for transcendent motivation, it is likely better fostered in feminine sociocultural contexts (preference for caring, cooperation and quality of life), such as Finland. Thus, the level of femininity/masculinity seem to indicate the boundaries of ethical behaviour in a sociocultural context. Accordingly, sociocultural contexts that are characterised by collectivism (and masculinity and high power distance) seem to be at risk of getting stuck with a masked CE approach, stagnating a move towards the CE.

Implications for Society, Managers and Policymakers

This study has practical implications for society, companies, policy makers and non-governmental organisations. First, distinct sociocultural environments can greatly impact motivations and approaches in implementing CE practices (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010). The relatively collectivistic, hierarchical, very masculine and restrained Japanese culture can make breaking patterns extremely difficult. Perhaps the informal, individualistic and indulgent culture in Finland better hosts change at the entrepreneur level. In Japan, the expectation of companies to participate in the CE is not as strong as in Finland, where norms have started to push companies to engage in sustainability. Thus, in Japan, the CE needs to accumulate more support from norms in society in addition to rules and regulations. This could provide collaboration opportunities for policymakers and non-governmental organisations in promoting CE concepts in their respective societies. Second, the findings regarding entrepreneurs not interested in the CE but still effectively leading businesses along its principles suggest implications for policy makers. Generating prerequisites for operating in the CE should be considered, for instance, through tax incentives for CE-based businesses. These insights can help spread the CE globally, as the current body of knowledge is highly concentrated in a Western European context. Third, companies expanding to and being founded in new regions can benefit from this study by better acknowledging that the CE approach needs to be tailored to specific sociocultural contexts. CE companies operating with partners in different regions also should consider the nature of the sociocultural environment towards it, which greatly influences their success.

Limitations and Further Research

This study has some limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, this exploratory study was limited in the generalisability of the findings. The study included companies from only two countries, all operating within the same industry. Thus, the insights should be applied in other regions and industries with caution. The study has highlighted motivations and sociocultural implications through an in-depth examination in a focused context (Gioia et al., 2013). Second, the study included one larger company, Marketplace, which can be considered a limitation. However, Marketplace is entrepreneurial, even start-up minded, which should make it comparable with the smaller companies in the sample. Also, Marketplace can arguably be seen as the most significant company application of CE in Japan. Third, this study examined CE approaches at companies in general, rather than focusing on companies that applied specific CE principles. As some studies have indicated, the principle of recycling is typically prioritised by regulation over the principles of reducing, reusing and recovering (Ranta et al., 2018). More practical and focused insights could be gained by addressing the relationship between society norms and the above three less-studied CE principles. CE approaches at companies could also be further studied by framing them as part of an emerging institution.

References

Agyemang, M., Kusi-Sarpong, S., Khan, S. A., Mani, V., Rehman, S. T., & Kusi-Sarpong, H. (2019). Drivers and barriers to circular economy implementation. Management Decision, 57(4), 971–994.

Allwood, J. M., Laursen, S. E., De Rodríguez, C. M. and Bocken, N. M. P. (2006) Well dressed. The present and future sustainability of clothing and textiles in the United Kingdom. Cambridge University, University of Cambridge Institute for Manufacturing

Amabile, T. M. (1993). Motivational synergy: Toward new conceptualizations of internal and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review, 3(3), 85–201.

Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497.

Bocken, N. M., de Pauw, I., Bakker, C., & van der Grinten, B. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 33(5), 308–320.

Brennan, G., Tennant, M., & Blomsma, F. (2015). Business and production solutions: Closing loops and the circular economy. In K. Kopnina & E. Shoreman-Ouimet (Eds.), Key issues in environment and sustainability (pp. 219–239). Routledge.

Ciulli, F., Kolk, A., & Boe-Lillegraven, S. (2020). Circularity brokers: Digital platform organizations and waste recovery in food supply chains. Journal of Business Ethics, 167, 299–331.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 173–208.

Corvellec, H., Stowell, A. F., & Johansson, N. (2021). Critiques of the circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13187

Dacin, M. T., Goodstein, J., & Scott, W. R. (2002). Institutional theory and institutional change: Introduction to the special research forum. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 45–56.

Davidsson, P., Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2006). Entrepreneurship as growth: Growth as entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship and the Growth of Firms, 1(2), 21–38.

Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., & Leone, D. R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62(1), 119–142.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Current theory and research in motivation: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. 38, pp. 237–288). University of Nebraska Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Dossa, Z., & Kaeufer, K. (2014). Understanding sustainability innovations through positive ethical networks. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(4), 543–559.

European Commission (2015). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Available from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:8a8ef5e8-99a0-11e5-b3b7-01aa75ed71a1.0012.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

Frei, R., Jack, L., & Brown, S. (2020). Product returns: A growing problem for business, society and environment. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(10), 1613–1621.

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362.

Gao, J., & Bansal, P. (2013). Instrumental and integrative logics in business sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(2), 241–255.

Gehman, J., Glaser, V. L., Eisenhardt, K. M., Gioia, D., Langley, A., & Corley, K. G. (2018). Finding theory–method fit: A comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27(3), 284–300.