Abstract

Artificial intelligence ethics requires a united approach from policymakers, AI companies, and individuals, in the development, deployment, and use of these technologies. However, sometimes discussions can become fragmented because of the different levels of governance (Schmitt in AI Ethics 1–12, 2021) or because of different values, stakeholders, and actors involved (Ryan and Stahl in J Inf Commun Ethics Soc 19:61–86, 2021). Recently, these conflicts became very visible, with such examples as the dismissal of AI ethics researcher Dr. Timnit Gebru from Google and the resignation of whistle-blower Frances Haugen from Facebook. Underpinning each debacle was a conflict between the organisation’s economic and business interests and the morals of their employees. This paper will examine tensions between the ethics of AI organisations and the values of their employees, by providing an exploration of the AI ethics literature in this area, and a qualitative analysis of three workshops with AI developers and practitioners. Common ethical and social tensions (such as power asymmetries, mistrust, societal risks, harms, and lack of transparency) will be discussed, along with proposals on how to avoid or reduce these conflicts in practice (e.g., building trust, fair allocation of responsibility, protecting employees’ autonomy, and encouraging ethical training and practice). Altogether, we suggest the following steps to help reduce ethical issues within AI organisations: improved and diverse ethics education and training within businesses; internal and external ethics auditing; the establishment of AI ethics ombudsmen, AI ethics review committees and an AI ethics watchdog; as well as access to trustworthy AI ethics whistle-blower organisations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

While AI ethics is a blooming field, there has been little research conducted on how organisations and businesses integrate ethical practices or how AI practitioners negotiate/mediate ethical values and integrate these values in their workplace. There is even less research being conducted on what happens when the AI practitioner’s values clash with those of their organisation. Recently, we have witnessed a number of high-profile clashes between AI researchers and the organisations that they have work(ed) for, such as the much-publicised firing of Dr. Timnit Gebru and Dr. Margaret Mitchell, founders and leads of the AI ethics division at Google.Footnote 1

Gebru and Mitchell were AI ethics practitionersFootnote 2 at Google and their work involved analysing the social and ethical impact of using technologies, such as large language models, facial recognition, and natural language processing, which are some of the key technologies being deployed and used at Google. While they had some leeway to offer critical perspectives of the company, there was, and still is, an ongoing tension between the organisation’s business model and internal criticisms against their technologies. One of the factors that led to Gebru’s departure from Google was her critical analysis of using large language models (Bender et al. 2021). The paper that they co-authored examines the risks of large language models and the large datasets that AI are trained on.Footnote 3 The company deemed that their research was unsuitable for publication, did not meet their quality requirements, and Google gave Gebru the ultimatum to withdraw the paper or remove her name from it (Simonite 2021).Footnote 4 The reason given for this was because the article ‘didn’t meet our bar for publication’, Google’s AI lead, Jeff Dean, stated (Tiku 2020).

Gebru claims that these reasons were a smokescreen to stifle criticism against the company’s practices (Paul 2021). She claimed that Google implemented overly restrictive policy and attempted to censor their work. Gebru and Mitchell’s departure from Google left a bad taste in the mouth of those still working in the AI ethics division at Google, and also the AI ethics community as a whole.Footnote 5 Some also felt that this debacle was yet another example of a large multinational saying that they care about ethics, while demonstrating the opposite. For example, Meredith Whittaker stated “What Google just said to anyone who wants to do this critical research is, ‘We’re not going to tolerate it’” (Simonite 2021). Many viewed the situation as silencing an important figure within the field. It sent a strong message to the AI ethics community: ‘AI is largely unregulated and only getting more powerful and ubiquitous, and insiders who are forthright in studying its social harms do so at the risk of exile’ (Simonite 2021). Thus, some have viewed the Google controversy as an example where the current ‘means and modes of negotiating disagreement are neither successful, nor constructive’ (Christodoulou and Iordanou 2021). The cases of Gebru and Mitchell pose the question of how much freedom AI practitioners have to integrate their ethical values when there are larger structural and organisational interests involved? Do individuals always (have to) bow down to the requirements of their organisation, and if not, how do they navigate these tensions and challenges?

Our paper aims to identify how AI professionals think about, implement, and respond to ethical challenges in the workplace; how their morals interact with the interests of the organisation that they work for; and what happens if there is a tension between their morals and the business model of the company they are employed by. We provide answers to these questions by first conducting an in-depth review of existing literature and secondly through a qualitative analysis of data collected during three workshops with AI practitioners (19 participants in total).

The overall structure of our paper is as follows: Sect. 2 will provide an analysis of the current state of literature relevant to our paper’s topic. Section 3 will describe the methodology employed in our qualitative analysis, and Sect. 4 will discuss the findings from three workshops with AI practitioners on these themes. Section 5 will conclude with a discussion on the findings from the workshops, reflecting on the value conflicts identified between AI practitioners and their organisations.

2 Literature analysis

The aim of our literature review is to provide insights about what values are being discussed at an organisational level in the development of AI, how individuals within those organisations view their ethical responsibilities, and how the two interact. The aim of this section is to find out what kinds of ethical practices are permitted, adopted, and prohibited within AI organisations. For the purpose of this paper, it was important to find relevant articles, rather than ones focusing on AI ethics or organisational ethics, in general. Articles were excluded if:

-

They were not explicitly addressing AI

-

They were not related to the ethical impacts of AI

-

They were not focused on organisations, or AI practitioners, implementing AI

We conducted a literature search through Scopus (August 2021), incorporating the following search query: TITLE-ABS-KEY (artificial AND intelligence OR ai OR machine-learning AND ethics OR ethical OR moral OR societal AND organisation OR business OR company OR companies OR businesses OR organisational OR organization OR organizational). This query resulted in over 700 hits, but was reduced when limiting our search to English-language publications (< 692 results); to only articles, books, book chapters and conference proceedings (< 574 results); to publications with the previous 10 years (< 520 results); and excluding disciplines that fall outside the scope of our research (e.g., physics and environmental science) (441 results).

However, most of these 441 documents were still not relevant to the specific angle of our research. Therefore, using our exclusion criteria, and based on the abstracts and keywords of the articles, this list was further refined down to only 17 relevant articles (see Table 1).

The main aim of this literature analysis, and also, our qualitative research, is to examine what types of AI ethics are being developed within organisations, what are the values of AI practitioners working in the profession, and the assessment of what happens when there is a tension between the two. Thus, our research questions for the focus of this paper are:

-

What type of AI ethics are being discussed in the literature at an organisation level, and how does this compare with in practice?

-

What are the values of AI practitioners, as discussed in the literature, and how does this compare with our qualitative sample study?

-

What does the literature, and our qualitative sample study, say about tensions between the AI ethics of organisations and the values of their employees? How can these tensions be resolved or reduced?

We structured our analysis of the literature and our qualitative study based (which will be discussed later in this paper in the qualitative analysis methodology section) on these three questions. However, it must be made clear that not all papers had equal significance for our analysis. Some papers did not meet any of the exclusion criteria when comprising the review, but upon evaluation, had very little relevant content for the purpose of our paper. Other papers, as will be seen in the following sections, proved to have much more content on the focus of our research.

The 17 papers were hand-coded, using the three categories outlined earlier: organisational AI ethics; values of AI practitioners; and when there is tension, conflict, or solutions, between the two. The papers were only analysed qualitatively to pinpoint the main messages expressed in this very short collection of relevant papers. This review is intended to provide a snapshot of what is being discussed in the literature to work as a contrast with our qualitative study later in the paper.

2.1 AI ethics within organisations

The majority of the literature that we analysed focused on organisational approaches to AI or how businesses should respond to AI-policy. The range of articles analysed provided a wide diversity of viewpoints about why, and how, AI organisations adopt and implement ethics. Most of the articles implied the reason behind the adoption of AI ethics within organisations is because of the economic incentive to do so (e.g., to secure funds), or because regulation requires it. For example, in Ryan et al. (2021), one of the interviewees stated that their focus on human rights was because it was a requirement to receive funding from the Austrian government. Another interviewee in the same paper stated that ‘no matter how well intentioned and principled AI ethics guidelines and charters are, unless their implementation can be done in an economically viable way, their implementation will be challenged and resisted by those footing the bill’ (Ryan et al. 2021). This was supported in other papers, stating that ethics is only implemented if it makes good business sense (Orr and Davis 2020).

In addition to this, most of the articles placed little emphasis on the responsibility of AI organisations; instead, stating that this was the job of governments (Caner and Bhatti 2020; Sidorenko et al. 2021). AI organisations were described as reactive, simply responding to policy, rather than taking initiative (Di Vaio et al. 2020). Stahl et al. (2021) propose that the mitigation of harms caused by AI should be a joint effort between organisations and policymakers by joining collectives such as the Partnership on AI and Big Data Value Association (Stahl et al. 2021).Footnote 6

However, the AI ethics guidelines created within these collectives were criticised as being too general or vague (e.g., policymakers, public sector, private sector, individuals, and collectives) (Ryan and Stahl 2021). Moreover, an over-involvement of AI organisations within policy may result in ‘ethics-washing’ or private interference in policy (Ryan and Stahl 2021).

The literature often illustrated this Catch-22 situation for AI organisations: if they are proactive and create AI ethics guidelines, they are seen as trying to counter the need for more restrictive AI regulation (i.e., attempting the easier self-regulation option). However, if they try to participate in the discussions on AI regulation, they are seen as trying to exert their power and control the policy-making process. If they simply take guidance from the latest policy frameworks, they are viewed as reactionary, only initiating ethical practices when it is actually forced upon them.Footnote 7

2.2 The values of AI practitioners

The study by Orr and Davis (2020) focused on how AI practitioners should implement ethics during their work with AI (Orr and Davis 2020). Their paper focused on interviews conducted with 21 AI practitioners (Orr and Davis 2020): seven from the private sector, seven from the public sector, and seven academics working in AI research. They noticed that there is very little attention being given to the question of the ethics of AI practitioners, despite the fact that AI practitioners are often the ones directly interacting with, and creating, the AI (Orr and Davis 2020).

A finding from Orr and Davis (2020) is that AI practitioners first evaluate if their actions are legal and how they fit within the parameters of legislation (Orr and Davis 2020). Many of the interviewees stated that ethics comes second, while others said that it is a ‘nice to have’, but not necessary, function for their job. Others stated that their views on what is ethical is closely bound to what is legal. The interviewees also placed an emphasis on policymakers and organisational bodies for being responsible for deciding what is ethical or not (Orr and Davis 2020, p. 730). This point was also emphasised in AlSheibani et al. (2018).

In another study, Stahl et al. (2021) interviewed 42 professionals working in the field of AI, and they noted that most of the interviewees were aware and concerned about ethical issues related to AI. The respondents said that their organisations were already implementing ethical principles, guidelines, or best practices to avoid problematic issues and promote ethical values. The approaches discussed ranged from internal ethics guidelines, review boards, stakeholder engagement sessions, responsible data science practices, and codes of ethics (Stahl et al. 2021).

In one of the case studies, it was noted that even when an AI practitioner is well-intentioned and wants to implement ethics, it is often difficult to do so because of their lack of training in the area (Ryan et al. 2021). There are, of course, several very obvious instances where discrimination, bias, and harm arise from AI, but there are also many nuanced and complex issues that AI practitioners must deal with (Ryan et al. 2021). A different paper stated that this may be aided through training and soft skill development, such as ‘collaboration, creativity, and sound judgment’ (Trunk et al. 2020, p. 900).

2.3 How AI practitioners implement ethics in their roles

In the Orr and Davis study,Footnote 8 interviewees were aware that their organisations had ethics mottos, guidelines, and codes, but were unable to recite them or describe them (2020). Despite this, they felt adamant that their organisations upheld ethical values and were bound by an ethical approach to AI; indicating that the exact specifics of their approach were less important than the overarching idea that ethics was instilled throughout the organisation (despite the fact that they could not recount what these ethics were about) (Orr and Davis 2020).

AI practitioners are hired to operate under certain conditions, with objectives and goals to reach. These are usually in the context of maximising profits, user engagement, developing better software, and so forth (Orr and Davis 2020). One of the interviewees in Orr and Davis (2020) stated that this often comes at the expense of what is ethical, but did not elaborate upon how this tension could be resolved. Also, one interview discussed the difficulties with making trade-offs in impartial ways: ‘Quite often we will make…trade-offs naively and in line with our own experiences and expectations and fail to understand the implications of those trade-offs for others…We can assess all of the trade-offs, but we still don’t weigh them in impartial ways’ (Orr and Davis 2020, p. 729).

Therefore, it is often difficult for AI practitioners to operate in an impartial way, so many revert back to legal restrictions and their organisation’s codes to guide them in their actions. In addition to this, AI practitioners often feel obliged to follow their organisation’s guidelines, rather than implement independent ethical judgment:

Participants felt bound by the expectations, mandates, interests, and goals of more powerful bodies. At the same time, practitioners have technical knowledge which those who commission (and often oversee) their work, do not. Thus, practitioners cannot act with full discretion, yet must exhibit independent efficacy (Orr and Davis 2020, p. 725).

AI practitioners have the expertise to develop these technologies and without them, the technology would not be possible. Therefore, there are many situations where managers within AI organisations do not know, or understand, how the technology will function in particular situations. The AI practitioner may sometimes have better insights into this because they have been closely working with the technology. They need to be able to bring this on-board, rather than simply ‘follow instructions’ from someone who has less hands-on experience with AI. However, this is not to imply that managers do not understand AI products and that it is only AI practitioners who have an in-depth knowledge of the product. Managers may have a much stronger understanding of the bigger picture that the AI product is fitting into, a perspective that AI practitioners may not (and are not expected to) have. Constructive cooperation between managers and practitioners would arguably result in a stronger and more ethical product. Besides, it is not always the case that moral values come into conflict with financial motivations; literature in business ethics has shown that good ethics is the smarter and more financially beneficial business decision and, therefore, morals and financially savvy business decisions can co-exist (Solomon 1997).

3 Qualitative analysis methodology

For our thematic analysis, we analysed data from three 3-h workshops with different groups of AI stakeholders. The workshops took place in the context of the H2020 project SHERPA (https://www.project-sherpa.eu/). The workshops were part of a larger empirical study, in particular, with a twofold objective: (a) to examine AI professionals’ values in the workplace and (b) to examine the effectiveness of engagement in dialog and reflection on reasoning and AI design, extending previous studies showing the effectiveness of engagement in dialog and reflection on reasoning (Iordanou 2022a, b; Iordanou and Rapanta 2021; Iordanou and Kuhn 2020). The present study focuses on the first objective, namely, to examine AI professionals’ values. Using qualitative analysis of three group discussions among AI professionals, we aimed to acquire a better understanding of how AI professionals incorporate ethical reflection in their day-to-day activities, how these ethical values and practices relate to their organisations’, and if there are instances when these clash, how do/did the participants respond.

The workshops took place via Microsoft Teams in June and July of 2021 and the organisers of the events recorded and transcribed these discussions (with the written and oral consent of the participants). Furthermore, during the transcription and analysis, the participants’ identities were pseudonymised for greater privacy protection. The audio data of the study was saved on password-protected computers, which only the researchers have access to. The data will be deleted after 5 years of publication of the project. The research methodology, including data collection and data management, were submitted for approval to the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee, responsible for assessing ethics-related issues of research projects. The data collection began after approval was granted.

A total of 19 individuals participated in the workshops, 15 men and 4 women, recruited from SHERPA partners’ personal contacts.Footnote 9 The professions of the participants can be seen in Table 2.

The workshops were conducted in English, and each workshop had 2–3 facilitators. The workshops began with a brief introduction about the project itself, the aims of the workshops, and an overview of values identified through the course of our project.

The first part of the workshop consisted of splitting the participants into groups and relocating them to virtual breakout rooms. In these rooms, the participants worked in pairs, describing their most important professional value and an event from their professional life that demonstrated how they responded to, implemented, or reflected about, this value in practice.

This was shortly followed by a presentation of a scenario for the participants to discuss (see Appendix 1). They brainstormed different values that they could identify from the scenario, and why/how these values were important. Participants were divided into two smaller groups and were tasked to work as a team to respond to the scenario. They used a digital file to keep track of their discussions and were given an hour to discuss how they would approach the assignment. Within these breakout groups, we used prearranged questions to enhance discussion (see Appendix 2).

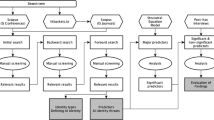

Afterwards, the workshops were analysed using a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006), which can be understood as ‘a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organizes and describes [the] data set in (rich) detail’ (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 79). The codes created were based on an analysis of the transcripts from the workshops, and overall, we followed Braun and Clarke’s six stages of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 87): (1) initial data familiarisation; (2) generation of initial codes; (3) search for themes; (4) review of themes in relation to coded extracts; (5) definition and final naming of themes; (6) production of the report (see Fig. 1).

Braun and Clarke's (2006) six stages of thematic analysis

The data were analysed using the data analysis software NVivo (Version 2020). Given that the project was an extension of a much larger project, with short time frame, only one researcher was involved in the data analysis to ensure consistency throughout the coding. The researcher discussed their findings, concerns, and ideas with the rest of the team during additional meetings and after sharing the initial codebook with them.Footnote 10 The purpose of the discussions was to ‘reflexively improv[e] the analysis by provoking dialogue between (O’Connor and Joffe 2020, p. 6).

When coding, the following themes were initially outlined: empathy, persistence, creativity, human dignity, agency and liberty, inclusiveness and bottom-up approaches, responsibility, technical robustness, transparency and ‘doing technology right’. After analysing these themes, there were each grouped into the three categories of how they were relevant for the AI ethics of organisations, the values of AI practitioners, or whether they were representative of the tensions between the two (or, of course, if they provide solutions to these tensions). These results can be seen in the next section where we outline our findings.

4 Findings

What became clear on analysis of the output from the workshops was that many of the topics being discussed fell within the same three overarching categories outlined in the literature review (the AI ethics of the organisations, values of AI practitioners, and the interactions between the two). Therefore, we structured this section in the same manner.

4.1 AI ethics within organisations

The discussions about the AI ethics within practitioners’ organisations, especially in the plenary sessions, were more general, reflecting aspects and issues about the industry as a whole, rather than about one specific (named) organisation. The main themes that arose when discussion AI ethics within organisations were: transparency, reputational damage, compliance, responsibility, and regulation vs. free market.

4.1.1 Transparency

One of the main themes that arose in the discussion of organisations’ AI ethics was transparency. For instance, one participant stated that companies should be transparent to their customers (Participant 2, W3).Footnote 11 For example, if hackers are successful and breach the company’s servers, then it is important that the company quickly informs those whose data may have been breached.

4.1.2 Reputational damage

However, the participant did not mention any explicit reference to this being done because it is the ethical thing to do, but instead, because it would reduce the damage to the company. This arguably reflects a position whereby AI practitioners view the interests of the customer as secondary to the interests of the company. Another participant stated that transparency is only relatively important within the industry: ‘in my field transparency is very dependent on who the client is, it's not the highest value completely’ (Participant 3, W3).

4.1.3 Compliance

A different, more critical approach was provided by another participant (Participant 2, W1), who stated that organisations only care about what is legal, despite the explicitly unethical outcomes of their actions, referring to the ad-driven consumer culture that disempowers the autonomy of individuals to choose, create, and flourish freely. They stated that people are being manipulated by ‘five, or six big companies in California’, who sell ads, provide fixed mobile services, and do not allow people ‘room to grow as individuals and to be intellectually curious’ (Participant 2, W1).

4.1.4 Responsibility

In addition to the theme of transparency, responsibility was a contentious point of discussion across all three workshops, with most participants saying that the organisations should definitely have some responsibility to protect vulnerable users, while one individual was staunchly against such a position. The latter stated that it is not the responsibility of the tech company to protect vulnerable users, partly because this task is too contentious and vague, leaving too much room for subjective and diverse interpretation, and partly because it would effectively mean limiting the capacities of organisations to perform their tasks. He was adamant that being too general about the responsibility of AI companies is not helpful (participant 4, W1).

4.1.5 Regulation vs. free market

Participant 3 (W1) further stated that companies should allow (adult) individuals make their own choices, rather than limiting their options. The companies should protect human rights and act ethically, but should not dictate the decisions of people and should not ‘delve into the spiritual or political decision making’ (Participant 4, W1). In other words, this responsibility was something that fell out of the realm of companies and instead fell into the domain of the state, and in some cases ‘ethics’ or ‘values’, he argued, were the responsibility of spiritual actors.

4.2 The values of AI practitioners

The discussions in the workshops around participants’ individual values and how they apply or integrate them within their workplaces were insightful and touched upon a number of specific ethical themes. The themes discussed throughout these interactions were: technical robustness, project-oriented goals underpinned ethical implementation, how compliance related to the public good, participation and inclusion, flexibility and creativity, empathy, agency, and responsibility.

4.2.1 Technical robustness

Not surprisingly, for most participants, the starting point was ensuring technical robustness of their technologies and ensuring that they are fit-for-purpose. This was often the primary concern for the developers in the workshops, but the reasons for prioritising it diverged.

4.2.2 Project-oriented goals for ethics

Some participants took a ‘success’ or ‘project’ oriented position, placing technical robustness as their primary focus merely because it resulted in successful projects. Although some individuals wanted to ensure that they followed all legal requirements for the benefit of their team, the company, and for their clients, this was still related back to the success of the project. If technical robustness was not implemented, it ‘could negatively affect the design’ and if a product is produced without taking that into consideration, ‘it could completely fail’ (Participant 3, W3).

4.2.3 Compliance and the public good

Other individuals detailed that they wanted to ensure that they followed all legal requirements and standards to avoid high fees and punishments (Participant 3, W3). While some indicated that they wanted to ensure technical robustness for ethical reasons (indicating that it is the right thing to do or for the ‘public good’), most emphasised the importance of the success of the project, avoiding fines, or penalties resulting from breaches of regulation or legislation.

4.2.4 Participation and inclusion

When the participants discussed the design and development of AI, some stated that they try to create open, inclusive, and participatory discussions and decision-making within their teams (Participant 2, W2). There was a strong emphasis on ‘co-creating’ and ‘participatory discussions’, and also creating a dialogue with communities for whom the technology is being designed: ‘it's more important to have inclusivity in mind, so having a more open approach to everything so that comes with having more, like keeping an open mind to making changes and, maybe changing some of the priorities that we had for project’ (Participant 2, W2).

4.2.5 Flexibility and creativity

Flexibility and adaptability were also reiterated by other participants, with one individual stating that they place a strong emphasis on the value of resilience and perseverance to ensure the best solutions are implemented (Participant 1, W2). Two participants stated that AI practitioners must be creative in their approaches (Participants 1 and 2, W3), a value which is often lost within large organisations: ‘Creativity is something that is forgotten a little bit. A lot of people get tied up with their work, tied up with the task they have to do, and they don't stop to think about how they might do something differently’ (Participant 1, W3).

4.2.6 Empathy

Another participant placed a strong emphasis on empathy throughout the workshop, and stated that this was the most important value for her (Participant 1, W1). Empathy was referred to as ‘the ability to see different perspectives’ and it was argued that while this was an integral element for respect, communication and generally a positive and empowering team work environment, it was often not practiced because people are not aware that they need to make an effort to practice this value—it is not just something that is ‘given to you’ (Participant 1, W1). The participant also argued that empathy was useful for addressing diversity in the digital context: stepping into the shoes of others and gauging what ‘different people…may need, for example from the software’.

4.2.7 Agency (libertarianism vs. paternalism)

One of the most interesting themes discussed during the workshops was the idea of human agency, with some proposing staunch libertarian perspectives of individual decision-making, while others advocated strong paternalistic approaches. One participant stated that human agency was the most important value and that individuals should be allowed the freedom to make decisions about what kinds of data they want to provide AI companies, and these companies should be upfront about how their data will be used (Participant 5, W1). Another participant disagreed, claiming that the end-user and the general public do not actually want to make these kinds of decisions (Participant 2, W1). They want others to take care of these issues, such as the AI company, regulators, or the government. The participant stated that ‘maybe human agency is actually too much’ and argued that the public often ‘want other people to look after them and to protect them’ (Participant 2, W1). Issues such as privacy, transparency, and fairness, they argued, should be ensured by the government and organisations developing AI (Participant 2, W1), a point which was supported in the literature (AlSheibani et al. 2018; Orr and Davis 2020).

4.2.8 Responsibility

In terms of responsibility, Participant 2 (W1) stated that developers should take responsibility for their actions, which entailed taking ownership and liability ‘for your own actions’. Responsibility is important in a professional context for developers to create AI in an ethical way, but it is also the responsibility of the end-user to work with the AI: ‘And we talk about responsibility in terms of software development and the possible implications of technologies, but also [it] is about our responsibility for ourselves and our actions and how we use technology’ (Participant 2, W1).

4.3 How AI practitioners implement ethics in their roles

During our discussions with the participants, they discussed how they implement ethics in their roles and some also detailed past experiences of tensions and conflicts between them and their employers. They shared some interesting insights and we have categorised these as:

4.3.1 Lack of transparency

Participants discussed some past value conflicts with their organisations; for example, one participant quit a job because of, what they viewed as, the organisations’ unethical behaviour. They were an early-career professional, enjoyed their job, and had good relationships with their colleagues and the company, but they felt that there was a serious lack of transparency within the organisation: ‘I think, we were basically building a business on the on top of the ignorance of our customers. Which were not really understanding what we were selling them. So yeah, I decided to change something’ (Participant 4, W1).

4.3.2 Benefit for society was lacking

Participant 4 (W1) left the company because it was not creating something that was good for society. The company was cutting corners, and the participant felt that the technical robustness of their product was seriously lacking. The participant stated that they wanted to produce something that was beneficial for society and AI development should not just be about making money. The organisation was selling solutions that were subpar and the participant felt forced to rush them through. It was very important for the participant to work on something that produces a positive societal change, and now that they work for a cybersecurity company, they are far more motivated in their job: ‘we kind of fight the bad guys (hackers) in a way’ (Participant 4, W1).

4.3.3 Inconsistent organisational strategy

In another case, a participant left their job because they felt that the strategy and methodological approach was seriously inconsistent. The organisation was using data from flawed research, which the participant confronted their employer about, telling them that this was ‘not a robust piece of research’ (Participant 5, W1). Participant 5 further elaborated how this situation really tested their moral compass:

I couldn't, I didn't feel from an ethics point of view that I could stand over this piece of research. So, there was an ongoing tussle about this over about 6 months where I kept trying to bring in different perspectives around how they could improve the situation and eventually that just didn't work. […] it was too embedded in their culture too, for me to be able to change it. So, I ended up leaving (Participant 5, W1).

4.3.4 Organisational resistance to change

Both participants noted that these situations were avoidable and unnecessary. The companies should have taken their views on board and implemented more ethical approaches. In particular, Participant 5 (W1) went to great lengths to bring about change within the organisation over many months, but was met with resistance, stubbornness, and lack of adaptability.

4.3.5 Speed vs. quality

In addition to these two examples, many other participants felt that there was often a challenge between balancing their own morals with the goals of their organisation.

Often, the participants discussed the ideal within the industry of doing things fast, promoting innovation over everything else, and the proneness to taking shortcuts (a point which was also reflected earlier in Orr and Davis 2020). Most participants stated that they did not like this part of their job because it often leads to technically faulty products, which may cause harm to those using them. There was a clear top-down pressure on developers to choose speed over quality, which often frustrated the participants.

4.3.6 Pressure on early-career developers

This issue is particularly difficult for young developers who are expected to do their work without getting into the politics or ethics of their job: ‘it's actually a huge problem in this in the modern software development, especially for junior developers, you come to work, you do something and then you have a pressure from the business to do things fast in a bad way’ (Participant 3, W2). While Participant 3 (W2) acknowledged that companies need to work efficiently and effectively, ‘there are things in the software development you just have to do well to not to cause any potential harm. Meaning things like privacy protection or authentication or safety or whatnot’ (Participant 3, W2).

5 Discussion

At the beginning of this paper, we reflected upon the situation of Timnit Gebru and her split from Google. What is interesting about this situation, and which was reflected in the workshops, is that AI practitioners often feel vulnerable when working for large tech companies. Participants 4 and 5 (W1) both discussed how they had to leave their organisations because of the unethical conduct of the organisation and the lack of responsiveness to change. They felt as though they were too small to initiate structural change. This raises a few questions: is this a problem because there are not enough people within the organisation concerned about the issue? Is it because the issue is not receiving public attention? Or is it a general disinterest on the part of large tech companies to act ethically? In addition to these questions, there are also deeply embedded fears about losing one’s job, the different power asymmetries inherent within organisational structures, and the real challenge of not being seen as “a troublemaker”, which could lead to ostracization from one’s job, long-term career, and profession.

Regarding Google, the organisation has a very mixed track record on ethical standards, but there have been examples where Google took a radical shift in its practices when put under pressure by its employees. In 2018, 3000 Google employees wrote an open letter to the CEO Sundar Pichai condemning the company for developing AI for the Pentagon. This AI would be used in drones in war, which would (presumably) result in the death of many innocent civilians. Google employees claimed that the company should not partake in the business of war. Google halted their contract with the Pentagon, bringing about a success story of ethical action created by employee empowerment. However, would Sundar Pichai have had such a change-of-heart if this letter did not receive media attention? Would he have changed position if the letter was only signed by 50 or 100 Google employees? How far would Google have gone if no light was shone on their dubious affairs?

Perhaps, Participant 3 (W3) was correct when they said that transparency within the tech industry is often not valued, a point which was also reflected by Timnit Gebru (Tiku 2020). AI companies may develop technologies that have specific functions, but how those technologies are used is not always clear. Organisations may not be transparent about how their AI will be used, which was shown in the outrage of Google employees when they found out about the Pentagon deal.

What became apparent during the course of the workshops was a strong emphasis to abide by what is legal. Many of the participants stated that their organisations only cared about what is legal, even if this explicitly contravenes what is (often, glaringly) ethical. This point can also be demonstrated in the Google case. To be clear, Google were not doing anything illegal by selling AI to the Pentagon. While it was not illegal, the Google employees deemed this to be unethical.

However, perhaps this also goes back to what Participant 4 (W1) mentioned when discussing the responsibility of AI organisations to protect vulnerable people from AI is too vague and open to interpretation. Perhaps AI companies cannot hope to prevent all possible misuses and impacts of their AI and that more specific examples need to be given. Of course, there is also a flipside: if AI organisations require very specific evidence about what kinds of violations will be caused by their AI, then there is room for them to claim ignorance. For instance, Google could have stated that they adamantly protect human rights and implement ethical guidelines in their development of AI and are simply uncertain how the Pentagon may use their AI in practice. Clearly, companies will not have full knowledge about how all of their customers will use all of their AI, but there are many instances (such as the Pentagon case) where claiming ignorance is neither realistic, believable, nor ethical.

There is no silver bullet for organisations to ensure that all of their AI will be used in an ethical way. Nevertheless, ensuring inclusiveness, co-development, and participatory decision-making (Participant 2, W2), may help minimise some of these harms. Still, this should be legitimate and thoughtful inclusiveness, rather than being implemented solely for appearance or ‘participation washing’ (Ayling and Chapman 2021; Sloane et al. 2020). For example, if Google implemented better inclusiveness and participation within the decision-making process, and had a more effective sounding-board with their employees about the Pentagon case, then this issue could potentially have been avoided.

It is clear from the Google-Pentagon case, the Google-Gebru case, and the workshops that we carried out, that it is important for AI practitioners to use and constantly develop and reflect upon their moral values and conscience. Although to differing degrees, the workshop participants felt a responsibility towards how AI is developed, deployed, and used. Therefore, it is important that AI practitioners stay well-informed, educated, and are able to bring their skills and expertise on-board in their roles. These tools will better enable practitioners to integrate ethics into their everyday professional practices. As Carter (2020) argues AI practitioners should see this as an opportunity, not a threat, to their daily working lives:

For the information professional the impact of AI and ML [machine learning] technologies is not just in how it may alter our future roles, but it will also impact our organizations and our customers in many different ways and we need to be aware and able to respond to those positives and negatives as well (Carter 2020, p. 65).

Within a democratic context, AI practitioners should be able to express their concerns or even challenge the ethical decisions of their organisation. To do so, it is crucial to have avenues or forums to discuss these concerns with the company and be able to initiate change if they identify injustices and harms taking place internally. However, as we have seen from the workshops and the Google examples, this is not always possible in real-life where tensions between financial interests and moral values ensue. Often, change requires a degree of public shaming or controversy to initiate action. This raises the question: how truly ethical are the actions of large AI organisations if they are only motivated by their reputation or economic incentives?

Furthermore, there is not always one clear way that employees can initiate collective action within their companies. AI practitioners are often left in uncertainty about a clear-cut way for implementing change. For example, Google reversed their deal with the Pentagon after receiving 3000 employee signatures, but after Gebru’s departure, the same amount (3000) of employees (and an additional 4000 academics, engineers, and colleagues) signed a letter voicing their disapproval of the company’s behaviour, which went unheeded (Schiffer 2021; Tiku 2020).

While AI ethics guidelines and regulation are a good starting point for ensuring that AI is ethical (Jordan 2019), AI practitioners should also feel empowered to implement these values and not simply follow the directions of the client or company, which could lead to very unethical practices (as identified in Orr and Davis 2020). Empowerment is ‘important because it ensures that people feel a greater sense of ownership in the solutions that they are building. They become more capable of solving problems that really matter to their users and customers’ (Gupta 2021). Management should implement ‘training programs for ethical awareness, ethical conduct, and competent execution of ethical policies and procedures, and these programs should cover the ethical deployment and use of the system’ (Brey et al. 2021, p. 72). This should ‘encourage a common culture of responsibility, integrating both bottom-up and top-down approaches to ethical adherence’ (Brey et al. 2021, p. 72).

It has been suggested that large AI organisations implement internal ethics boards, ethics committees, and ethics officers, to deal with these concerns and challenges inclusively and transparently (Stahl et al. 2021). Some of the issues discussed in this paper could be resolved through:

the institution of an ethics officer or an ethics committee, or the assignment of specific ethics responsibilities to different staff, such as the compliance manager, supplier manager, information security manager, applications analyst and/or IT operations manager. […] Individuals should be able to raise concerns with the ‘ethics leader’ within their department, or have the option to discuss them with an ethics leader at a different level in the organisation, the ethics officer, or an externally-appointed affiliate. There should be the possibility to escalate concerns at all levels within the organisation (Brey et al. 2021, p. 72).

There also needs to be a certain level of independence and freedom to challenge the norms of the organisation, internally. Individuals within these organisations should be protected to conduct their research to ensure that the AI is developed and deployed in an ethical way. These organisations need to act on the feedback and advice from their employees, rather than simply using AI ethics teams and responsible AI groups as a façade (Lazzaro 2021). As Timnit Gebru stated in a recent interview, without labour protection, whistle-blower protection and anti-discrimination laws, anything that AI ethicists do within large organisations ‘is fundamentally going to be superficial, because the moment you push a little bit, the company’s going to come down hard’ (Bass 2021).

Therefore, there should be accessible routes for the AI practitioner to follow, externally, if they feel their concerns are not being listened to. For example, establishing independent AI ethics ombudsmen to investigate these matters, AI ethics bodies (nationally or internationally) where the AI practitioner can follow-up about these issues, and an AI ethics whistle-blowing group to allow the general public insights about the nefarious practices taking place with the organisation. There should be ‘a process that enables employees to anonymously inform relevant external parties about unfairness, discrimination, and harmful bias, as a result of the system; that individual whistle-blowers are not harmed (physically, emotionally, or financially) as a result of their actions’ (Brey et al. 2021, p. 44).

A recent example for the need for external whistle-blower protection is the case of Frances Haugen against her former employer, Facebook. Haugen started working at Facebook in 2019 as a product manager in Facebook’s civic integrity team, ‘which looks at election interference around the world’ (Milmo 2021a, b, c). Haugen quit Facebook in May 2021 because the company was not doing enough to prevent harmful content and material on its platform, she claims. She leaked thousands of internal company documents and had a 60-min interview on CBS to detail the misdeeds of the company (Milmo 2021a). She claimed that the company always put profit and company benefits over what was good for users and society, specifically tailoring their algorithms to maximise profitable (albeit, harmful) material (Milmo 2021a). She stated that ‘Facebook has realised that if they change the algorithm to be safer, people will spend less time on the site, they’ll click on less ads, they’ll make less money’ (Milmo 2021a).

Going to the press or accessing whistle-blowing outlets is neither simple nor easy for AI practitioners. For instance, their former organisations may have staunchly denied such accusations, in a similar way as Mark Zuckerberg has with Haugen’s allegations (Milmo 2021b). In addition to this, there is also the fear of a public smear campaign against them by their former employer or that it becomes too difficult to obtain work after such allegations, affecting their long-term career prospects. Individuals who quit their job and publicly whistle-blow about their former employer’s unethical behaviour should feel they have the agency to do so as well as legal and societal protection; if they are doing a public service, then they should not be mistreated afterwards. Policymakers need to implement stronger policies to protect these individuals and allow them to come forward with their information in the assurance that they are doing the right thing and will not be chastised for doing so.

However, notwithstanding the importance of AI practitioners having strong moral compasses and a cognitive understanding of what their values are, it is also worthwhile acknowledging the limits and risks of AI practitioners making decisions solely on their own morals and reasoning. Instead, it is essential for AI practitioners to understand their values in the organizational and societal context of the company and society in which they are a part of and to pursue avenues of deliberation and collaboration, rather than make executive decisions without adequate dialogue. If an AI practitioner were to make decisions based on their own morals without consulting other value sets (for example, AI Ethics policies) then there is a high risk of bias in the system due to the AI practitioner prioritising values differently to the society they are designing for. AI practitioners are essential in AI development but making siloed executive decision when it comes to ethics will create more problems than solutions.

Finally, our paper highlighted the value of engaging AI professionals in discussions about their values and the alignment of their values with their professional practice. There is evidence from previous research, that engagement in discussion, especially when discussion involves participants with diverse views (Iordanou and Kuhn 2020), promotes individuals’ reasoning on topical issues. Engagement in discussion has supported participants’ ability to consider multiple dimensions on an issue, particularly the ethical dimensions, when reasoning about a topic (Iordanou 2022a, b). Whether engagement in constructive discussion can promote greater consideration of values and value-based design, among AI professionals, is an open question, yet a noteworthy one for future research to investigate.

6 Conclusion

The main aim of this paper was to identify the values that guide AI practitioners in their roles, how they view the AI ethics of their organisations, and what happens when there is a tension or conflict between the two. Through a review of the literature and an analysis of three workshops, we investigated how AI practitioners negotiate and mediate ethical values in their workplace and the challenges and resistance they face when attempting to initiate change. We also explored several suggestions of steps that could be taken (both internally and externally) when there is an ethical dilemma or challenge. Our contribution lies in that we shed light on an under researched angle: the possibilities and limits of individual values and the practice of ethics by individuals within wider institutional structures (the lack of discussion was illustrated earlier in our literature review, specifically, the shortage of articles that were relevant for Sects. 2.2 and 2.3).

Our main findings from Sect. 3 were that much of the literature focuses on the legal ramifications for organisations not abiding by AI regulation. There was scepticism about AI organisations, claiming that much of their initiative towards ethical AI is rooted in economic interests and how they are portrayed to the public. Some articles were critical of companies’ AI ethics guidelines, claiming that it is their attempt to self-regulate and have a soft policy to avoid stricter AI regulation. There was very little discussion in the literature around the ethics of the AI practitioner, as an individual unit, and how they can implement ethics in practice.

As our workshops show, AI practitioners do find morals and values incredibly important, some so much they will even leave their jobs if they feel these are not respected. However, at the same time we saw that there were several cases that presented a dissonance when it came to applying these morals. This presents an interesting mismatch between the ideological desires of employees on the one hand and their motivation to implement their ethics in practice. Some participants in the workshops placed an emphasis on what is legal because it was the easiest procedure to take and for fear of getting in trouble. This may be a sign that individuals are more likely to follow ethical principles if they are concrete and presented as ethical codes of conduct, just as they feel safer and more comfortable to follow legal ones because these are provided in more clear and concrete terms. They were also often unsure about how to implement ethics in practice; so here we see that there is a lack of institutional resources as often internally companies do not have in place well-defined structures and processes for doing so. One can conclude, therefore, that if more ethics education and training is initiated within these organisations and provided to the AI practitioners, the latter may be more willing, confident and able to implement them in practice (Iordanou et al. 2020).

Others, were used to focus on ‘getting the job done’ and doing this fast, and again this reflects both a gap and an opportunity: if AI organisations resist change, then AI practitioners can only do so if they act as ‘agents’ of change. This entails rethinking the ‘quick and dirty’ mindset and prioritising digital and ethical well-being (Burr and Floridi 2020) above speed and absolute profit.

More research into the particular educational competencies required for revaluation and rethinking of values in the context of everyday work practices is, therefore, necessary. We also suggest that organisations implement internal AI ethics boards, ethics committees, and ethics officers, to help respond to their employees’ concerns. Externally, there should be independent AI ethics ombudsmen, external AI ethics boards and bodies (nationally or internationally), and AI ethics whistle-blowing organisations, to inform the public about harmful practices within these organisations. Ethical values are indeed a prerequisite for one to implement ethical-oriented goals and work policies and change is not easy. But as other social movements have shown—for instance Fridays for Future—one individual’s determination can be enough to trigger a global movement. Therefore, there is still optimism to see small opportunities for change within the wider profit-driven dynamics of the AI industry.

Notes

Note: Google contends that Timnit Gebru resigned and that they simply accepted her resignation.

When we refer to AI practitioners in the paper, we mean those who are either developing, designing, deploying, integrating, using, or assessing AI within their respective organisations.

Gebru and her co-authors claim that the environmental and financial costs of training large AI models is extremely high and debate the need for more research to do so in a more sustainable way. She also argues that such models hold the potential to incorporate racist, sexist, homophobic, and abusive language.

A full overview of the situation can be found in this Wired article: https://www.wired.com/story/google-timnit-gebru-ai-what-really-happened/.

The organisation did itself no favours in this aftermath, with other reported censorship of AI researchers’ work in the company (Reuters 2021).

There is no straightforward answer to this dilemma and because it veers more towards the organisational challenges of implementing ethics, rather than the tension between organisations and their employees values, it goes beyond the scope of this paper.

This is the only article included in this section as it was the only study that exclusively examined the tension and conflict between organisations and the values of AI practitioners.

The team made great efforts to ensure a gender balance, but this was not possible because of the wider, structural gender imbalances in the field and the low response rate of the female participants invited to be involved in the workshops.

The research team of the current paper consists of four researchers (three female and one male) from four different disciplinary backgrounds: social science and politics; computer science; philosophy; and psychology.

The “W” denotes workshop, hereafter.

References

AlSheibani S, Cheung Y, Messom C (2018) Artificial intelligence adoption: AI-readiness at firm-level. Presented at the Proceedings of the 22nd Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems—Opportunities and Challenges for the Digitized Society: Are We Ready? PACIS 2018

Ayling J, Chapman A (2021) Putting AI ethics to work: are the tools fit for purpose? AI Ethics 1–25

Bass D (2021) Google’s Former AI Ethics Chief Has a Plan to Rethink Big Tech. Bloomberg.com

Bender EM, Gebru T, McMillan-Major A, Shmitchell S (2021) On the dangers of stochastic parrots: can language models be too big? In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency. pp 610–623

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101

Brey P, Lundgren B, Macnish K, Ryan M, Andreou BL, Jiya T, Klar R, Lanzareth D, Maas J, Oluoch I, Stahl B (2021) D3.2 Guidelines for the development and the use of SIS. https://doi.org/10.21253/DMU.11316833.v3

Burr C, Floridi L (2020) The ethics of digital well-being: a multidisciplinary perspective, in ethics of digital well-being, a multidisciplinary approach. In: Burr C, Floridi L (eds) Philosophical Studies Series. Cham, pp 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50585-1_1

Caner S, Bhatti F (2020) A conceptual framework on defining businesses strategy for artificial intelligence. Contemp Manag Res 16:175–206. https://doi.org/10.7903/CMR.19970

Carter D (2020) Regulation and ethics in artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies: where are we now? Who is responsible? Can the information professional play a role? Bus Inf Rev 37:60–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266382120923962

Christodoulou E, Iordanou K (2021) Democracy under attack: challenges of addressing ethical issues of AI and big data for more democratic digital media and societies. Front Polit Sci 71:1–17

Clarke R (2019) Principles and business processes for responsible AI. Comput Law Secur Rev 35:410–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2019.04.007

Cubric M (2020) Drivers, barriers and social considerations for AI adoption in business and management: a tertiary study. Technol Soc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101257

Di Vaio A, Palladino R, Hassan R, Escobar O (2020) Artificial intelligence and business models in the sustainable development goals perspective: a systematic literature review. J Bus Res 121:283–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.019

Du S, Xie C (2021) Paradoxes of artificial intelligence in consumer markets: ethical challenges and opportunities. J Bus Res 129:961–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.024

Dwivedi YK, Hughes L, Ismagilova E, Aarts G, Coombs C, Crick T, Duan Y, Dwivedi R, Edwards J, Eirug A, Galanos V, Ilavarasan PV, Janssen M, Jones P, Kar AK, Kizgin H, Kronemann B, Lal B, Lucini B, Medaglia R, Le Meunier-FitzHugh K, Le Meunier-FitzHugh LC, Misra S, Mogaji E, Sharma SK, Singh JB, Raghavan V, Raman R, Rana NP, Samothrakis S, Spencer J, Tamilmani K, Tubadji A, Walton P, Williams MD (2021) Artificial intelligence (AI): multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int J Inf Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.08.002

Gupta A (2021) How to build an AI ethics team at your organization? [WWW Document]. Medium. URL https://towardsdatascience.com/how-to-build-an-ai-ethics-team-at-your-organization-373823b03293. Accessed 10 May 21

Holtel S (2016) Artificial intelligence creates a wicked problem for the enterprise. Presented at the procedia computer science, pp 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.109

Iordanou K (2022a) Supporting critical thinking through engagement in dialogic argumentation: taking multiple considerations into account when reasoning about genetically modified food. In: Puig B, Jiménez-Aleixandre MP (eds) Critical thinking in biology and environmental education: facing challenges in a post-truth world. Springer, Berlin

Iordanou K (2022b) Supporting strategic and meta-strategic development of argument skill: the role of reflection. Metacogn Learn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-021-09289-1

Iordanou K, Kuhn D (2020) Contemplating the opposition: does a personal touch matter? Discourse Process 57(4):343–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2019.1701918

Iordanou K, Rapanta C (2021) “Argue with me”: a method for developing argument skills. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631203

Iordanou K, Christodoulou E, Antoniou J (2020) D4.2 Evaluation Report. De Montfort University. Online resource. https://doi.org/10.21253/DMU.12917717.v2

Jordan SR (2019) Designing artificial intelligence review boards: creating risk metrics for review of AI. Presented at the International Symposium on Technology and Society, Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISTAS48451.2019.8937942

Lazzaro S (2021) Are AI ethics teams doomed to be a facade? Women who pioneered them weigh in. VentureBeat. URL https://venturebeat.com/2021/09/30/are-ai-ethics-teams-doomed-to-be-a-facade-the-women-who-pioneered-them-weigh-in/. Accessed 10 May 21

Loureiro SMC, Guerreiro J, Tussyadiah I (2021) Artificial intelligence in business: state of the art and future research agenda. J Bus Res 129:911–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.001

Milmo D (2021a) How losing a friend to misinformation drove Facebook whistleblower. The Guardian

Milmo D (2021b) Facebook ‘tearing our societies apart’: key excerpts from a whistleblower. The Guardian

Milmo D (2021c) Mark Zuckerberg hits back at Facebook whistleblower claims. The Guardian

O’Connor C, Joffe H (2020) Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods 19:160940691989922. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

Orr W, Davis JL (2020) Attributions of ethical responsibility by artificial intelligence practitioners. Inf Commun Soc 23:719–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1713842

Paul K (2021) Two Google engineers quit over company’s treatment of AI researcher. The Guardian

Reuters (2021) Google to change research process after uproar over scientists’ firing. The Guardian

Ryan M, Stahl BC (2021) Artificial intelligence ethics guidelines for developers and users: clarifying their content and normative implications. J Inf Commun Ethics Soc 19:61–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-12-2019-0138

Ryan M, Antoniou J, Brooks L, Jiya T, Macnish K, Stahl B (2021) Research and practice of AI ethics: a case study approach juxtaposing academic discourse with organisational reality. Sci Eng Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00293-x

Schiffer Z (2021) Timnit Gebru was fired from Google—then the harassers arrived [WWW Document]. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/22309962/timnit-gebru-google-harassment-campaign-jeff-dean. Accessed 16 Sept 21

Schmitt L (2021) Mapping global AI governance: a nascent regime in a fragmented landscape. AI Ethics 1–12

Sidorenko EL, Khisamova ZI, Monastyrsky UE (2021) The main ethical risks of using artificial intelligence in business. Lect Notes Netw Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47458-4_51

Simonite T (2021) What really happened when google ousted Timnit Gebru. Wired

Sloane M, Moss E, Awomolo O, Forlano L (2020) Participation is not a design fix for machine learning. ArXiv Prepr. ArXiv200702423

Solomon RC (1997) It’s good business: ethics and free enterprise for the New Millenium. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham

Stahl BC, Antoniou J, Ryan M, Macnish K, Jiya T (2021) Organisational responses to the ethical issues of artificial intelligence. AI Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01148-6

Tiku N (2020) Google hired Timnit Gebru to be an outspoken critic of unethical AI. Then she was fired for it. Wash. Post

Trunk A, Birkel H, Hartmann E (2020) On the current state of combining human and artificial intelligence for strategic organizational decision making. Bus Res 13:875–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-020-00133-x

Acknowledgements

This project (SHERPA) has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework Programme for Research and Innovation under the Specific Grant Agreement No. 786641.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Scenario

Scenario 2: A problem has come up. A new social media platform is going to be developed (similar to Facebook/Twitter/LinkedIn).

Some of the developers (Group A) of the platform support that the platform should be freely accessible to the public and have advertisements as their source of revenue. To use advertisements the team will employ AI and Big Data to allow for automated social media posts, and optimisation of social media campaigns for the advertisers. AI and Big Data, also referred to as Smart Information Systems (SIS), will create an SIS that will be able to figure out what works best using advanced analytics, and also decode trends across social media to find the best target audience for each product. To do this an SIS-based social media monitoring mechanism will be developed. As a secondary feature of the platform, the developers would not mind using SIS to also create some interesting features for the users at a later stage, however, their main focus for the initial product is the use of SIS for smart advertising.

Other developers (Group B) within the company support that there should be a registration fee for users, for covering the revenue of the company, with no advertisements. They still feel that AI and Big Data should be used only to provide more services to the users and that the users should be able to at least consent to data collection, e.g., by actively selecting a specific service. For example, the developers will offer options to the users to use some features of the social media platform that are SIS-powered, such as face recognition, the platform will use AI and Big Data to recognise the users face in photos and based on that provide filter options, etc. Another feature of the social platform will be the option for companies to advertise their job posts, and AI and Big Data will be used to create a service to match the platform users with potential jobs. In both these examples, the user will be able to control whether they would like to have the use of filters or job recommendations as part of their profile.

The developers basically agree on the use of AI and Big Data but disagree on the emphasis they should place on using SIS for improving user-centred features, and they also disagree on the use of SIS for advertising.

Consider that this assignment has been assigned to your team. Work in your team to clarify the key design and development objectives of this task.

Appendix 2: Workshop questions

-

1.

Why do you think there is disagreement about the use of advertisements as a source of income from this new platform?

-

2.

Who should ultimately be responsible for making the decision about whether advertisements will be used?

-

3.

Who should ultimately be responsible for making the decision about face recognition or job recommendation features are developed?

-

4.

What are some potential vulnerabilities from developing face recognition or job recommendation features?

-

5.

Consider the scenario that each one of the two different platform implementations are used widely within a community. What positive and negative societal impacts do you foresee?

-

6.

Who should be held responsible if personal data is leaked in any of these situations? [accountability]

-

7.

What possible implications regarding environmental sustainability could the features of this platform have? Is this an important aspect for you? Why? Do you think it should be addressed more in future work? Why/why not? [environmental sustainability]

-

8.

What possible implications regarding human rights and liberties could the features of this platform have? Is this an important aspect for you? Why? Do you think it should be addressed more in future work? Why/why not? [human agency and human rights/diversity and fairness/inclusion and social justice]

-

9.

What possible implications regarding transparency could the features of this platform have? Is this an important aspect for you? Why? Do you think it should be addressed more in future work? Why/why not? [transparency]

Appendix 3: Codebook

Name | Description | Files | References |

|---|---|---|---|

Accountability | 1 | 3 | |

Added value | 1 | 4 | |

Advertisements | 1 | 2 | |

Algorithmic bias and design bias | 1 | 2 | |

CA-Human agency and responsibility too much | 1 | 1 | |

Causes of disagreement (according to participants) | 1 | 1 | |

Company-centric approach | 1 | 1 | |

Comparison to medical ethics (not influencing peoples choinces around health) | 1 | 1 | |

Confidence | 1 | 1 | |

Consider the systemic impact of the product at various levels | Is it a real changer? How will it affect the economies? The audience’s response? | 1 | 1 |

Measurable performance metric | 1 | 1 | |

Contribute to the survival of the company (financially) | 1 | 1 | |

Contribution to human flourishing | 1 | 3 | |

Create a product that adapts to changing societal needs | 1 | 1 | |

Creativity | 2 | 3 | |

Democracy | 1 | 1 | |

Different meanings of ethics and responsibility so clearly establish, agree and communicate the design principles within the company | 1 | 2 | |

Does the least harm to the most people | 2 | 3 | |

Doing technology right | 1 | 1 | |

Empathy and perspective-taking | 2 | 2 | |

Empower users | 1 | 1 | |

Environmental sustainability (challenges, responsibilities, how do you deal with it) | 1 | 2 | |

Freely accessible | 1 | 2 | |

Good communication—feedback loops to see if there is compliance with initial design choices | 1 | 1 | |

Human Agency | 2 | 6 | |

Creative ways to offer choice | 1 | 1 | |

Human dignity and freedom and liberty | 1 | 1 | |

Human stupidity—lack of common sense | 1 | 3 | |

Identifying stakeholders values | 1 | 1 | |

Inclusion and participatory decision-making | 1 | 2 | |

Individual and Societal well-being | 1 | 1 | |

Motivation to go to work | 1 | 1 | |

Over-regulation | 1 | 1 | |

Persistence | 1 | 1 | |

Positive societal impact | 1 | 1 | |

Preference for subscription service | 1 | 1 | |

Pressure by companies to do things fast even if it causes harm | 1 | 2 | |

Privacy and Data Governance | 2 | 8 | |

Profitability (conflicts with other values) | 1 | 2 | |

Protection | 1 | 2 | |

Ranking values according to positive or negative impact | 1 | 2 | |

Responsibility and Respect | 2 | 12 | |

More information ('as people know more') contributes to the responsibility movement | 1 | 1 | |

Positions of power and control (should be responsible) | 1 | 1 | |

Responsibility of the company to build a sustainable business model | 0 | 0 | |

Responsibility regarding the environment (political forces, individual responsibility, and social pressure) | 1 | 1 | |

Responsibility to educate | 1 | 1 | |

Responsibility to regulate advertisements | 0 | 0 | |

State responsibility through regulators | 1 | 1 | |

Who is responsible for Algorithmic bias and for reducing it | 0 | 0 | |

Security | 1 | 1 | |

Standards part of guiding principles of a company | 1 | 3 | |

Sustainable revenue (business) model | 1 | 2 | |

Technical proficiency and robustness | 3 | 4 | |

Transparency | 3 | 8 | |

Transparency which contributes to agency | 1 | 2 | |

Trust | 1 | 3 | |

User-centric approach (value added, good experience, stability, security) | 1 | 2 | |

Vulnerable groups at risk | 1 | 2 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryan, M., Christodoulou, E., Antoniou, J. et al. An AI ethics ‘David and Goliath’: value conflicts between large tech companies and their employees. AI & Soc 39, 557–572 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01430-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01430-1