Abstract

Ethical dilemmas are common in the neonatal intensive care setting. The aim of the present study was to investigate the opinions of Swedish physicians and the general public on treatment decisions regarding a newborn with severe brain damage. We used a vignette-based questionnaire which was sent to a random sample of physicians (n = 628) and the general population (n = 585). Respondents were asked to provide answers as to whether it is acceptable to discontinue ventilator treatment, and when it actually is discontinued whether or not it was acceptable to use drugs which hasten death unintentionally or intentionally. The response rate was 67 % of physicians and 46 % of the general population. A majority of both physicians [56 % (CI 50–62)] and the general population [53 % (CI 49–58)] supported arguments for withdrawing ventilator treatment. A large majority in both groups supported arguments for alleviating the patient’s symptoms even if the treatment hastened death, but the two groups display significantly different views on whether or not to provide drugs with the additional intention of hastening death, although the difference disappeared when we compared subgroups of those who were for or against euthanasia-like actions. The study indicated that physicians and the general population have similar opinions regarding discontinuing life-sustaining treatment and providing effective drugs which might unintentionally hasten death but seem to have different views on intentions. The results might be helpful to physicians wanting to examine their own intentions when providing adequate treatment at the end of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of modern medicine has made it increasingly possible to offer life-sustaining treatment to patients who are suffering from life-threatening conditions and, thereby, to save patients who would otherwise have died. This is the bright side of the story. The darker side is that sometimes healthcare is saving lives at the price of a very low quality of life (Wijdicks and Rabinstein 2002). These latter prospects might help to explain why many older people are writing advance directives in which they declare that life-sustaining treatment should be withhold or withdrawn, e.g. to save them from ending up in a persistent vegetative state. Such advance directives might be valuable for healthcare professionals when deciding whether or not to discontinue life-sustaining treatment, although surrogates’ own values might also influence decisions (Kuehlmeyer et al. 2012; Marks and Arkes 2008).

Unlike decisions involving formerly competent patients in persistent vegetative states, decisions regarding newborn children in similar conditions cannot be based on advance directives. Accordingly the question arises how physicians should act and reason in such situations: ought physicians to continue life-sustaining treatment or withdraw it, depending on the parents’ wishes? If such patients survive, but with severe brain damage, should considerations regarding expected low quality of life matter (Goggin 2012)? A subsequent question is actualised if the life-sustaining treatment is actually withdrawn and the newborn baby is imminently dying: is it then acceptable to provide treatment with the foreseen effect of also hastening death (Tibbals 2007)? Would it be acceptable in such settings to provide treatments that in addition deliberately hasten death? Such an additional intention would, in the eye of the law, constitute an act of euthanasia. Key issues associated with the two latter questions are whether or not intentions are morally relevant and how this may affect people’s trust in healthcare (Lindblad et al. 2012).

These are all normative questions and substantial normative arguments would therefore be needed in order to take a stand on them. However, as a point of departure for a normative argument, it is interesting to find out how those potentially affected by these questions feel and reason about them (Mercadante and Giarratano 2012). Accordingly, in order to shed light on how the public and physicians think about these issues, we have conducted a survey among physicians concerned, such as intensivists and paediatricians, neonatologists included, as well as the population at large.

Methods and participants

We used a vignette-based questionnaire containing different questions in relation to a specific case regarding a newborn child suffering from severe brain damage—see Box 1. Briefly, the baby is dependent on ventilator treatment; in the long run the child might survive and live without the ventilator, but with low or very low quality of life. Fixed arguments for and against the continuing of life-sustaining treatment are provided. Response options are fixed in terms of estimating the argument as strong, rather strong, rather weak and no argument at all. The results are presented as proportions of those who estimated the argument as strong or rather strong. After having answered these questions the respondents were also asked to prioritise the arguments. This prioritisation allowed us to divide the samples into groups who support arguments for continuing or discontinuing life support treatments. We also invited the respondents to provide own prioritised reasons. The vignette is now developed and the baby is additionally afflicted by pneumonia and sepsis and all parties concerned agree to withhold antibiotics and to discontinue the ventilator treatment. The baby breathes with difficulty and develops convulsions. The question is whether or not the physician should provide effective drugs which also have the foreseen but not intended side-effect of hastening death. The respondents are also asked whether it would be acceptable if the treatment was provided with the additional intention of hastening death—an action similar to euthanasia in all but name. We are using this specific question as a background variable when analysing other responses. Response options are fixed in terms of agreeing completely or to a large extent and disagreeing completely or to a large extent. The results are presented as proportions of merged agreeing responses and the questions/statements can be seen from the Tables 2, 3 and 4. In order to examining whether or not a majority would support discontinuation of life-sustaining treatment and whether or not they would support providing an alleviating drug which could hasten death we also asked to state which of the arguments the participants found most important. Finally, the respondents were asked about what would happen to their trust in healthcare if physicians abstained from providing alleviating drugs and what would happen to trust if physicians in such situations provided alleviating drugs in order to hasten death, also intentionally. The response options were: trust would decrease, increase or not be influenced. Finally we asked about age, sex, specialty, and respondents’ general trust in healthcare.

The questionnaire was mailed to a random sample of intensivists and anaesthesiologists (n = 299), paediatricians and neonatologists (n = 329). The physicians were randomly selected from a commercial database (Cegedim/Stockholm) involving all physicians and their specialties in Sweden. We asked the responders to specify their specialties and 40 were intensivists, and 155 anaesthesiologists giving a response rate of 63.2 %; 137 were paediatricians and 87 neonatologists resulting in a response rate of 66.7 %. No age limitation was applied to physicians. We merged the subgroups of physicians, since there were no identifiable significant differences in response-pattern between them. A random sample of the general population (n = 585) received a similar questionnaire and the response rate was 45.6 %. This sample was recruited from a company associated with the Swedish tax authorities. In order to contrast a previous, similarly conducted study, we used a sample from the same region: Västerbotten County in northern Sweden (Rydvall and Lynøe 2008). The age interval selected was between 20 and 70 years. For demographic data on the two populations, see Table 1. The random samples of physicians and the general population was from companies that supply names and addresses commercially. The questionnaire was send by mail autumn 2010. After 2 weeks, those who had not responded received a reminder and after further 2 weeks a second reminder. After having received the answers we discarded the envelope with the code number; consequently, it was no longer possible to identify individual participants. We found no differences in response pattern between those who answered first and last out of three reminders.

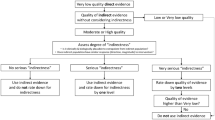

The results are presented as odds ratios (OR) and proportions with 95 CI. When the CIs are not overlapping we have interpreted as if we had performed a hypothesis test (e.g. χ2-test) and the p value would have been less than 0.05. When the proportions are overlapping we have added p-values. EpiCalc 2000 was used to calculate OR.

The study was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee at Umeå University, Dnr 2010-105-31 M.

Results

The sex distribution between the physicians and the general population differs somewhat as well as did the age distribution see Table 1.

Continue or discontinue ventilator treatment?

A majority of both physicians and the general population prioritised arguments for discontinuing ventilator treatment [52 % (CI 48–57) vs. 58 % (CI 52–64)] (p = 0.1). The strongest of the prioritised arguments were that of minimising suffering, followed by the quality of life argument—see Table 2. The most prioritised argument for continuing ventilator treatment was consideration towards the parents, followed by the argument that the primary task of physicians is to protect and preserve life—see Table 2. We found an inverse association between the protecting-life-argument and the quality-of-life-argument among physicians [OR 4.7 (CI 3–7.3)] and the general public [OR 5.5 (CI 3.1–9.6)]. Similarly we also identified an inverse association between the protecting-life-argument and the comprehensive-suffering-argument for physicians [OR 5.7 (CI 3.4–9.5)] and the general public [OR 4.7 (CI 2.3–9.7)].

The only difference between the groups of physicians was found regarding whether or not to consider parents’ wish to continue. Compared to anaesthesiologists and intensivists [58 % (CI 51–65)], a significantly larger proportion of paediatricians and neonatologists [74 % (CI 68–80)] supported the parents’ wish argument (p = 0.001). However there was no difference between anaesthesiologists and intensivists or between paediatricians and neonatologists.

Provide treatment which might even hasten death?

Shortly after the ventilator treatment has been discontinued, the patient develops convulsions, and in order to alleviate potential suffering the physician gives the patient anticonvulsant drugs, which may have the foreseen side-effect of hastening death. A large majority of both physicians and the general public supported and prioritised the argument that the physician should actually provide such treatment, even considering the foreseen but not intended side-effect—see Table 3. There were however, some differences between the two groups when considering whether or not the physician, in order to minimise suffering, should offer effective drugs with the additional intention of hastening death. Among the general population a majority supported that argument [70 % (CI 64–76)] and approximately 17 % prioritised it, compared to 23 % (CI 19–27) among the physicians, 3 % of whom prioritised the argument (p < 0.001).

How is trust influenced?

The subsequent questions concerned what would happen to the respondents’ trust in healthcare if effective treatment against convulsions was provided and the treatment could also (intentionally and non-intentionally) hasten death. A majority in both groups stated that trust would decrease if doctors in such situations abstained from using effective drugs that unintentionally hastened death—61 % (CI 55–67) among the general population and 81 % (CI 77–85) among the physicians (p < 0.001).

The euthanasia issue

We also asked what would happen to the respondents’ trust in healthcare if doctors in such cases used effective drugs in order to intentionally hasten death. Compared to the general public [29 % (CI 23–35)], significantly more physicians stated that their trust would decrease [62 % (CI 57–67)] (p < 0.001)—see Table 4a.

Finally, we made a selection of the respondents who supported the argument that the physicians, in order to minimise the total suffering, should provide drugs with the additional intention of hastening death. Of those who accepted such a procedure, rather few stated that such practice would decrease trust—15 % (CI 10–20) among the general population and 19 % (CI 11–27) among the physicians (p = 0.43)—see Table 4b. Similarly, we also found that among those who were against acting with the additional intention of hastening death, a majority in both groups stated that trust would decline: 62 % (CI 51–73) among the general public and 74 % (CI 69–79) among the physicians (p = 0.06)—see Table 4c. There were no significant differences in response depending on age, sex or specialities, apart from the few aspects mentioned above.

Discussion

When making decisions of whether or not to continue or discontinue a life sustaining treatment, the two groups provide almost similar response-pattern. Although it was a majority in both groups who prioritised arguments for discontinuing the treatment, it was not a large majority. The parents’ wish seems to be an important reason to both groups and particularly to the general population. Paediatricians and neonatologists are those who are used to discuss and negotiate such issues with the parents. This group of physicians, compared to the other physicians, significantly more tended to estimate this argument as stronger. Apart from one issue, the response-pattern regarding whether or not to provide effective drugs was also rather similar between the two groups. The issue which separated the two groups concerned the euthanasia-like argument, involving the intention to hasten death. We know that the general population is inclined to accept euthanasia or physician assisted suicide in Sweden, and we also know that Swedish physicians are more or less reluctant towards these issues (Lindblad et al. 2008, 2009). The present results might reflect these attitudes.

To continue or discontinue

In the case presented, the brain-damaged newborn baby might survive, eventually even without ventilator treatment, but with comprehensive brain damage and with long-term effects, most likely resulting in a very low quality of life including risks of severe suffering. According to most bioethical theories, considerations of future quality of life constitute a relevant argument for discontinuing ventilator treatment (Beauchamp and Childress 2001) and, as it seems from this study, to a large proportion of the public and physicians as well. But the reasoning in this context hinges on an accurate prediction of the future quality of life. The question whether or not continuing the ventilator treatment might be considered futile, depends on the possibility of making accurate predictions based on clinical data. But it seems obvious that futility in this context is related to the quality-of-life aspect, as well as the protecting life duty. The higher the quality-of-life-aspect is estimated, the more relevant seems the principle of protecting life and vice versa. A similar reasoning also seems valid when estimating the potential future suffering.

The reasoning might have been different if the patient was an elderly person who had lived a long life and who, e.g. due to a severe stroke, ended up in a persistent vegetative state (Rydvall and Lynøe 2008). It seems slightly easier to discontinue life-sustaining treatment for an older patient, particularly if he/she has made an advance directive or if it is possible to reconstruct some kind of hypothetic will which could support such a decision (4, 8). The results of the present study might reflect the complexity of the present situation regarding future uncertainties, compared to a situation involving elderly patients; the question in the present situation is dependent on uncertain empirical facts about the child’s future state. That is actually a relevant difference and might justify our tending to consider the two situations differently.

An important question is for whose sake the treatment is continued: the child’s or the parents’? If the treatment is continued for the parents’ sake, are we then using the child merely as a means and not an end in itself? Or are physicians reluctant to discontinue therapy for fear of medico-legal consequences (Jox et al. 2012)? These questions deserve to be further examined in future studies.

What about providing treatment that might hasten death?

When the patient develops convulsions and providing effective treatment might hasten death, the response pattern indicates that the issues regarding what to do seem to become more complicated. Compared to the first situation, where the physician’s primary task might still be considered as that of protecting and preserving life, this is not the case in a situation where the patient’s death is imminent. Ethically speaking, one’s primary duty in the present situation is to comfort the patient and minimise suffering. So what is actually the problem if such treatment is provided in order to treat convulsions and acceleration of death is a foreseen side-effect? And, furthermore, why should it matter whether the hastening of death is intended or not? In the present study, physicians in general seem to embrace the position that there is a morally relevant distinction between intended and unintended hastening of death, although the overarching purpose of both actions is to alleviate the patient’s suffering (Juth et al. 2010). The allegedly morally relevant distinction between the directly intended and foreseen effects might be described in the following manner: (1) to minimise suffering by intentionally shortening life, and (2) to minimise suffering by symptom control which might have the foreseen but unintended side-effect of shortening life. The general public seems to pay little attention to such a distinction. Ethically and legally it is not always possible to make sure whether or not the physician had the additional intention of hastening death. Accordingly, the question of intentions in this particular situation might be perceived as a rather unimportant, and might explain why the general public care less about these distinctions. The public care to a low extent about the foreseen/intended distinction, but this does not prove the distinction between foreseen and intended effects to be morally irrelevant. On the contrary, these simple observations make it interesting to further explore why physicians seem to care so much about the foreseen/intended-distinction. One explanation for their preoccupation with the foreseen/intended distinction is that this has been a part of the official ethical guidelines for physicians in Sweden, according to which a physician should not intentionally hasten death (Swedish Medical Association, http://www.slf.se/Etikochansvar/Etik/Lakarforbundets-etiska-regler/). However, this hypothesis is mere conjecture on our part: to find out why physicians put greater emphasis on this distinction, further investigations are needed. Another likely explanation is physicians’ fear of medico-legal consequences (see below) or that intentions tend to be ascribed after the event and depending on the outcome (Knobe 2003).

What happens to trust?

The question of neglect also arises when we ask hypothetically what the respondents think would happen to trust if physicians abstained from using effective treatments because they might hasten death. A presumption for this reasoning is that declining trust is a threat to healthcare and something that physicians would endeavour to avoid. With this in mind, it is rather surprising that 19 % of the physicians stated that their trust would not be influenced (or increased) if in such settings the physician abstained from using effective drugs. One explanation could be that at the time when the present study was conducted, a Swedish intensive-care physician was accused of mercy-killing in the end-of-life-treatment of a premature child suffering from comprehensive brain damage (Lynøe and Leijonhufvud Accepted). Many physicians, particularly intensivists, understood the attorney’s message to mean that it is better to be restrictive when providing treatment at the end of life than to face manslaughter charges, even though this might entail suffering for the patient.

The other question about trust concerned the intention of minimising suffering for an imminently dying patient, with the additional intention of hastening death. The fact that 38 % of the physicians responded that their trust would not be influenced or would actually increase when providing drugs with the additional intention of hastening death is interesting. It seems to be this euthanasia-like issue which explains how both physicians and the general population responded. Only apparently these intentions are more important to physicians compared to the general population. Focusing on physicians as well as representatives of the general population who are against euthanasia-like actions, intention matters, while among those who are in favour of euthanasia-like actions, intentions do not matter to the same degree.

Validity

The response rate was rather low among the general population. This might be due to the complexity of the questionnaire and to how concerned the respondents feel. The relative higher response rate among paediatricians also indicates that being concerned means something. Although we used randomised samples we were, due to confidentiality, not able to control whether or not the samples actually were representative for the concerned populations. However, we compared those who responded first with those who responded to the last reminder and identified no differences in response-pattern.

Using vignettes-based questionnaires entails a number of limitations. They do not represent real-life reasoning, and the respondents might opt for politically correct answers rather than authentic ones. But since the questionnaires were anonymous after the second reminder, we assume that many answers represent the respondents’ intuitive answers, and as such are not necessarily based on reflections and calculated political correct opinions. Since we merged the responses into those who found the arguments strong and rather strong or agreed completely and to a large extent, we might have lost nuances in response pattern. Furthermore, in order to highlight the ethical decisions, we constructed this questionnaire so that there was very little doubt about the prognosis. In real life, the long-term prognosis of severe conditions in newborns is often very uncertain.

Conclusions

The general population and physicians tend to have similar opinions regarding whether or not to discontinue life-sustaining treatment for a newborn child with severe brain-damage. But the two groups tend to have different opinions about whether or not to treat seizures with effective drugs and with the additional intention of hastening death. Compared to the general population, physicians seem to be more inclined to think that intentions are important. The difference, however, seems to disappear when we divided the groups into subgroups of those who were for or against a euthanasia-like action. The results might be helpful to physicians wanting to examine their own intentions when providing effective treatment at the end of life. The results might also be helpful when physicians try to help relatives examine their values.

References

Wijdicks, E.F.M., and A.A. Rabinstein. 2002. The family conference—end-of-life guidelines at work for comatose patients. Neurology 68(14): 1092–1094.

Kuehlmeyer, K., G.D. Borasio, and R.J. Jox. 2012. How family caregivers’ medical and moral assumptions influence decision making for patients in the vegetative state: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Medical Ethics 38(6): 332–337. doi:10.1136/medethics-2011-100373. Epub 2012 Feb 28.

Marks, M.A.Z., and H.R. Arkes. 2008. Patient and surrogate disagreement in end-of-life decisions: Can surrogates accurately predict patients’ preferences? Medical Decision Making 28(4): 524–531. doi:10.1177/0272989X08315244. Epub 2008 Jun 19.

Goggin, M. 2012. Parents’ perceptions of withdrawal of life support treatment to newborn infants. Early Human Development 88(2): 79–82. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.12.002. Epub 2012 Jan 9. Review.

Tibbals, J. 2007. Legal basis for ethical withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment from infants and children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 43(4): 230–234.

Lindblad, A., R. Löfmark, and N. Lynøe. 2008. Physician assisted suicide: A survey of attitudes among Swedish physicians. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 36: 720–727.

Lindblad, A., R. Löfmark, and N. Lynøe. 2009. Would physician-assisted suicide jeopardize trust in medical services? An empirical study of attitudes among the general public in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 37: 260–264.

Lindblad, A., N. Juth, and N. Lynøe. 2012. End-of-life decisions and the reinvented rule of double effect: A critical analysis. Bioethics. doi:10.1111/bioe.12001. Epub ahead of print.

Mercadante, S., and A. Giarratano. 2012. The anesthesiologist and the end-of-life care. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 25(3): 371–375.

Rydvall, A., and N. Lynøe. 2008. Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: A comparative study of the ethical reasoning of physicians and the general public. Critical Care 12: R13.

Beauchamp, T.L., and J.F. Childress. 2001. Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jox, R.J., A. Schaider, G. Marckmann, and G.D. Borasio. 2012. Medical futility at the end of life: The perspectives of intensive care and palliative care clinicians. Journal of Medical Ethics 38: 540–545.

Juth, N., G. Helgesson, M. Sjöstrand, N. Lynøe, and A. Lindblad. 2010. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) framework for palliative sedation: an ethical discussion. BMC Palliative Care 9: 20.

Swedish Medical Association. Physicians’ rules. http://www.slf.se/Etikochansvar/Etik/Lakarforbundets-etiska-regler/.

Knobe, J. 2003. Intentional action in folk psychology: An experimental investigation. Philosophical Psychology 16: 309–324.

Lynøe, N., M. Leijonhufvud. Police on an intensive-care unit—what can happen? J Med Ethics (Accepted).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rydvall, A., Juth, N., Sandlund, M. et al. To treat or not to treat a newborn child with severe brain damage? A cross-sectional study of physicians’ and the general population’s perceptions of intentions. Med Health Care and Philos 17, 81–88 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-013-9498-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-013-9498-9