Abstract

According to an influential line of thought, from the assumption that indeterminism makes future contingents neither true nor false, one can conclude that assertions of future contingents are never permissible. This conclusion, however, fails to recognize that we ordinarily assert future contingents even when we take the future to be unsettled. Several attempts have been made to solve this puzzle, either by arguing that, albeit truth-valueless, future contingents can be correctly assertable, or by rejecting the claim that future contingents are truth-valueless. The paper examines three of most representative accounts in line with the first attempt, and concludes that none of them succeed in providing a persuasive answer as to why we felicitously assert future contingents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that Belnap and Green’s version of the assertion problem, as we shall see, differs to some extent from the one discussed, for instance, by MacFarlane (2014), p. 202. Hence, it would be perhaps too hasty to speak simply of the assertion problem.

The reason of this choice is that if one identified branching-time theories simply to the view that there is no actual history and that future contingents lack truth values, then a considerable group of theorists, best represented by Peter Øhrstrøm and his colleagues, would automatically be excluded from the branching-time crowd. But this seems unjustified. After all, philosophers like Øhrstrøm are committed to the branching time representation while also accepting a privileged, actual course of events.

Some philosophers (e.g., incompatibilists), have argued that fatalism, so understood, implies that human beings have no freedom either in the sense that our actions are causally inefficacious or in the sense that —albeit causally efficacious— they are not freely performed. See Rice (2002) for a discussion.

Although the difficulties concerning the interpretation of Aristotle’s Chapter IX are well known, this is the solution that many of the interpreters nowadays attribute to Aristotle.

This result is a direct consequence of Łukasiewicz’s conviction that logical connectives, as in two-valued logic, must be truth-functional. More particularly, Łukasiewicz’s truth table of negation says that \(\sim \)p is indeterminate if p is indeterminate, while that of disjunction says that p∨ q is indeterminate if p and q are both indeterminate. Hence, it follows that (5) is indeterminate either. See Łukasiewicz (1920).

As it has been emphasized by Øhrstrøm (2009), pp. 19-21, the view that there is such thing as the actual future goes back to William of Ockham. In terms of Ockham’s theological weltanschauung, this means that all future contingents are either true or false, and that God foreknows their truth-value which depends on what will happen in the “true” future, as Ockham called it, namely the future part of the actual course of events.

A theory of this kind has been articulated by McCall (1976). On McCall’s view, the various “dead” branches are lopped off, as it were, by the objective temporal becoming. However, this does not mean that BT-frames are incompatible with the alternative view according to which the flowing of time is not objective. See Borghini and Torrengo (2013) p. 5.

To be precise, \(\alpha \supset \Box \alpha \) could be accepted by an Ockhamist even if F occurred in α —e.g., if α had a form p ∧ FPp. The fact is that it is difficult to precisely define “no trace of futurity” in non-metric language. See also Reynolds (2003) for a discussion.

It is common to define future-tensed sentences like (1) as gappy because supervaluationism, contrary to Łukasiewicz’s trivalent logic, allows for truth-value gaps.

As it is well known, supervaluationism preserves excluded middle by making ∨ not truth-functional with respect to super-truth: a disjunction can be true even if neither of its disjuncts is true. This way of making sense of excluded middle entails a duality with respect to truth-functionality: truth-functionality holds at the level of truth relative to histories —since for any history h (5) is true in h iff one of its disjuncts is true in h— but not at the level of truth simpliciter. This is why supervaluationism is usually considered a partially non-classical theory.

Of course, it may be doubted whether Thomason’s system is in fact an accurate representation of what Aristotle really said in the De Interpretatione IX. Be that as it may, in what follows I will not try to settle this question.

See Rosenkranz (2012), pp. 629–30, for a similar complaint.

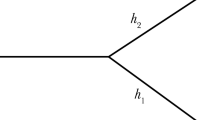

It is important to stress that within the branching-time framework there might be incomparable moments. However, for the sake of expository simplicity, I will assume that the moment of u and moment of a are instead comparable.

The case at stake is similar to those in which an assertion is incorrect because it fails to express a determinate content. To illustrate, suppose that someone asserts “that car over there is red” but that “over there” some cars are red and some are not, and the context (including the speakers intentions) does not settle which car the demonstrative “that” refers to. If so, one might be tempted to say that the assertion fails to express a determinate content, hence that it is incorrect. Adapting this case to future contingents and assuming the truth norm, it follows that branching concretists will always end up judging assertion of future contingents as incorrect.

See Evans (1985), p. 348.

Note that Thomason’s account has not been proposed as a solution to the assertion problem but to the so-called “initialization failure” — roughly, the problem of how to specify the semantic value of the history parameter since, due to indeterminism, the context of utterance is unable to select the history parameter required for making future contingents truth-evaluable. It is indeed for this reason that Prior (1967, p. 126) called the branch-dependent ascription of truth-value “prima-facie”. This, however, does not imply that one cannot provide a possible (and hopefully plausible) reconstruction of what Thomason might think about the assertion problem based on his semantic approach.

A similar example is discussed in Hattiangadi and Besson (2014), pp. 11-12. One possible supervaluationist’s reply regarding those cases in which it seems plausible to assert Fp, even though \(\sim \)Fp is still possible, namely those cases in which the probability of Fp is very high, might be as follows: since truth simpliciter is defined in terms of quantification over possible futures —and such a quantification can be restricted by contextual factors (it is often so)— the reason why it seems correct to assert Fp in a given context is that, in all the futures relevant for that context, Fp is true. In other terms, the relevant tree of that context is a tree where in all the branches Fp is true. In this way, supervaluationists can explain the apparent truth of Fp.

I believe this response fails for at least two reasons. Firstly, it seems that the irrelevance of the branches in which \(\sim \)Fp holds is based on the fact that those branches are very few. But being very few doesn’t mean being not relevant: on the branching picture, all the branches are ontologically on a par, therefore the irrelevance of some of them should not be explained by simply claiming that their number is very low. Some other reasons must be given to justify the restriction. Secondly, one may argue that supervaluationist’s reply can only work under the hypothesis that the norm to be employed cannot be the truth norm but a different norm according to which, roughly, one must assert only what is highly probable —where the high probability may be cashed out in terms of truth in the vast majority of possible futures. But, again, that doesn’t seem a solution if the problem is to make sense of assertion of future contingents while maintaining the truth norm.

See Stojanovic (2014), p. 40.

I should mention that in this section I did not discuss another reasonable norm, namely a justification norm, according to which one must assert that p, only if p is (well) justified. After all, it seems that a future contingent might be justified –i.e., we might have good evidence for it– and so correctly asserted even if the future is open. For expository reasons, the discussion of such a norm has been postponed in Section 8.1.

Note that I am not suggesting that to be a temporalist, as well as an eternalist, one must necessarily be committed to the existence of facts. As far as I know, temporalism and eternalism could also be couched in terms of events or state of affairs. So nothing should hinge on this for my purposes.

Belnap et al. (2001), p. 139, are explicit in endorsing eternal B-order relations.

Sweeney (2015), p. 7, raises similar worries. In addition, she argues that, insofar as Belnap et al. employ a static BT-model, they are also unable to solve the problem of how to evaluate past-tensed sentences. See McCall (1994) for an attempt to make sense of the the asymmetry in openness by means of the objective temporal becoming.

It should be stressed, however, that Belnap at al. do not actually adopt the norm-based account of assertion. That is, they do not try to explain the nature of assertion by pointing out the constitutive norms of its correctness. As Stojanovic (2014), p. 38, in fact notes, they seem to be more concerned with what she calls the “descriptive question”, namely the question of what conditions an utterance of a declarative future-tensed sentence must fulfill in order to count as an assertion.

See Hattiangadi and Besson (2014), p. 21, for a discussion. One way to support the line of reasoning just considered is to note that, since justification can be seen as a “guideline” for the truth of what we assert, it would seem odd to believe that (1) is justified if one knows from the start that (1) is not true. After all, it seems that the belief that (1) is justified should leave room for the possibility that (1) is true. But on MacFarlane’s view such a possibility is clearly ruled out in that (1) cannot be true.

See MacFarlane (2014), p. 101.

See Stojanovic (2014), pp. 39-43.

MacFarlane assumes that we hedge a future contingent because we think that it is truthvalueless. However, we similarly hedge statements that are sure to have a truth-value (it is now raining in Amsterdam) but that we are just not sure of: ”I think/Probably it’s now raining in Amsterdam”. Thus, hedging seems to be a general sign of epistemic uncertainty rather than a sign of a statement being truthvalueless. At any rate, as an anonymous reviewer pointed out, one might still have a different (i.e., deflationary) intuition about how future-directed assertions work. More specifically, one might contend that in some cases it doesn’t seem mandatory to interpret a flat-out assertion as literally true, as opposed to having a contextually determined (sufficiently high) degree of probability —so that anything that is sufficiently probable in a given context is also flat-out assertible in that context. For example, the prediction that the Reims Cathedral won’t quantum-tunnell into my living room five seconds from now can be flat-out assertible in our present context even though the event in question is physically possible and, if the future is open, it may very well occur in one of our future branches.

This suggests that MacFarlane’s strategy implies a version of error theory about assertion of future contingents —even if it should be emphasized that while in MacFarlane’s case we have that the proposition expressed by future contingents is settled true or false, standard error theorists tipically claim that all substantive normative statements are false.

As MacFarlane (2014), p. 230, himself recognizes, such a problem also afflicts Supervaluationism and Peirceanism and, more generally, all the views that take future contingents to be untrue.

Note that the argument against MacFarlane’s idea to interpret “Will: p” as “Probably (Will: p)” could even be strengthened: if all future contingents were interpreted along these lines, MacFarlane’s relativistic project would be pointless because the truth-value of the proposition “Probably (Will: p)” is independent of the context of assessment. In addition, observe that in the case of different speech acts, such as bets, the sentence “Will: p” should not be interpreted as “Probably (Will: p)”. It is in fact crucial for bets that the literal meaning is attributed to the sentence rather than to the “probabilistic” meaning (otherwise, I could win the bet that Hilary Clinton would win the 2016 US election, even after Donald Trump’s victory; after all, it was likely that she would win). See Belnap et al. (2001) for a discussion.

Thanks to Francesco Gallina for this suggestion.

I leave aside the issue of whether, in order to make sense of Ockham’s view, actuality must be formally represented. Iacona (2014), for instance, claims that Ockhamism and TRL should not be equated. Indeed, while the former is a philosophical conception concerning future contingents, the latter is a semantic apparatus. Iacona’s main point is that the actual course of events should rather be considered as an “hypothesis” about M. This supposition leads him to think that Ockhamism could be associated with both OC and the branching framework, without assuming that actuality must be formally represented as a specific parameter within the BT-model. A very similar point has been also recently pressed by Gallina (2018) and Wawer and Malpass (2018).

References

Belnap, N., & Green, M. (1994). Indeterminism and the thin red line. Philosophical Perspectives, 8, 365–388.

Belnap, N., Perloff, M., & Xu, M. (2001). Facing the future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Borghini, A., & Torrengo, G. (2013). The Metaphysics of the Thin Red Line. In Correia, F., & Iacona, A. (Eds.) Around the tree: Semantic and metaphysical issues concerning branching and the open future (pp. 105–126). New York: Springer.

Dummett, M. (1959). Truth. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, n.s., 59, 141–62.

Evans, G. (1985). Does Tense Logic Rest on a Mistake?. In Collected Papers (pp. 341–63). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gallina, F. (2018). In defence of the actuality principle. Philosophia, 46(2), 295–310.

Green, M. (2014). On saying what will be. In Nuel Belnap on Indeterminism and Free Action (pp. 147–158). Dordrecht: Springer.

Grice, P.H. (1989). Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hattiangadi, A., & Besson, C. (2014). The open future, bivalence and assertion. Philosophical Studies, 162(2), 251–271.

Iacona, A. (2014). Ockhamism without thin red lines. Synthese, 191, 2633–2652.

Lackey, J. (2007). Norm of assertion. Noûs, 41, 594–626.

Łukasiewicz, J. (1922). On Determinism. In Borkowski, L. (Ed.) Selected Works. 1970 (pp. 110–128). North-Holland: Amsterdam.

Łukasiewicz, J. (1920). On Three-Valued Logic. In Borkowski, L. (Ed.) Selected Works. 1970 (pp. 87–88). North-Holland: Amsterdam.

Malpass, A., & Wawer, J. (2012). A future for the Thin Red Line. Synthese, 188, 117–142.

MacFarlane, J. (2003). Future contingents and relative truth. Philosophical Quarterly, 53, 321–336.

MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment Sensitivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCall, S. (1976). Objective time flows. Philosophy of Science, 43(3), 337–362.

McCall, S. (1994). A model of the universe: Space-Time, Probability, and Decision. Clarendon Press.

Øhrstrøm, P. (2009). In defence of the Thin Red Line: a case for Ockhamism. In Models of time: humana.mente, (Vol. 8 pp. 17–32. (64: 581–602)).

Prior, A. N. (1967). Past, present and future. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Reynolds, M. (2003). An axiomatization of Prior’s Ockhamist logic of historical necessity. In Zakharyaschev, M., & Wolter, F. (Eds.) Advances in Modal Logic, (Vol. 4 pp. 355–370): King’s College Publications.

Rice, H. (2002). Fatalism. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/fatalism/.

Rosenkranz, S. (2012). In defence of Ockhamism. Philosophia, 40, 617–631.

Stojanovic, I. (2014). Talking about the future: Unsettled truth and assertion. In Brabanter, P. D., Kissine, M., & Sharifzadeh, S. (Eds.) Future Times, Future Tenses (pp. 26–43): Oxford University Press.

Sweeney, P. (2015). Future contingents, indeterminacy and context. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 96(3), 408–422.

Thomason, R.H. (1970). Indeterminist Time and Truth-Value Gaps. Theoria, 36, 264–281.

van Fraassen, B.C. (1966). Singular terms, truth-value gaps, and free logic. Journal of Philosophy, 63, 481–495.

Wawer, J. (2014). The truth about the future. Erkenntnis, 79, 365–401.

Wawer, J., & Malpass, A. (2018). Back to the actual future. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1802-zhttps://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1802-z.

Williams, B. (1973). Deciding to believe. In Problems of the Self (pp. 136–151): Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Santelli, A. Future Contingents, Branching time and Assertion. Philosophia 49, 777–799 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-020-00235-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-020-00235-0