George: Try and I’ll beat you at your own game.

Martha: Is that a threat George, huh?

George: It’s a threat, Martha.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Abstract

I introduce game-theoretic models for threats to the discussion of threats in speech act theory. I first distinguish three categories of verbal threats: conditional threats, categorical threats, and covert threats. I establish that all categories of threats can be characterized in terms of an underlying conditional structure. I argue that the aim—or illocutionary point—of a threat is to change the conditions under which an agent makes decisions in a game. Threats are moves in a game that instantiate a subgame in which the addressee is ‘under threat’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Perhaps not surprising when we consider how little discussion there has been of many socially relevant features of our linguistic practice. This has recently changed, with excellent recent discussion on topics like oppression (McGowan 2009), insinuation (Camp 2018), dogwhistles (Saul 2017, 2018), coded political speech (Khoo et al. forthcoming; Stanley 2015), and social meaning (Haslanger 2013) beginning to make waves in analytic circles (the notion of threats, specifically, as a way of silencing is discussed in Langton 1993). This paper owes much, both directly and indirectly, to these works and authors.

Searle and Vanderveken (1985) identify seven features of illocutionary force, including the illocutionary point (the characteristic aim of a type of speech act) and what they call the mode of achievement, which is how that aim is achieved. Though what is offered here is an account of the illocutionary point of a threat, I also raise some considerations throughout about how that aim is achieved (mode of achievement).

How exactly to characterize the illoctuonary point of a speech act—whether, for instance, it is the intended effect of the speech act, or the outcome associated with a particular convention—will differ depending on one’s general commitments to a theory of speech acts (see footnote 4; thanks to an anonymous reviewer for some comments here).

However, a theory of the illocutionary point of a threat does not constitute a full theory of the illocutionary force of a threat. It is not the aim of this paper to weigh in on a more general dispute in speech act theory between different accounts of what it is to perform a speech act (i.e., between intention-based accounts of speech acts and convention-based accounts of speech acts; see Harris et al. (2018) for an overview of the various positions one might take with respect to a general theory of speech acts). But regardless of whether or not we want to give, say, a fundamentally intention-based characterization of the speech act of a threat, there is still an interesting and important question to be asked about the sort of action you perform when you threaten someone. Focusing on the illocutionary point of a threat allows us to say something about threats in general.

No English sentence is by default a threat—for any sentence to count as a threat, contextual supplementation is required. An utterance of the sentence, “If you come any closer, I’m going to zap you” might be issued to threaten against someone coming closer. But it might also be issued to let the hearer know that the speaker’s sweater is full of static energy, and so she will inadvertently ‘zap’ whoever gets near her. That said, many of the example sentences I use will be recognizable as threats without much context.

Thanks to Hans Kamp for suggesting this particular terminology for this class of threats.

It is also typically made explicit that the speaker will be the one to perform this action. This seems to be part of what marks the (fuzzy) distinction between categorical and covert threats.

This is a fairly bold sociological claim, and I only stand by it to the extent that many of the cases I identify going forward seem completely ordinary.

We might think that the conditional/categorical distinction carries over to the category of covert threats as well. For the purposes of this paper, it is enough to acknowledge a distinction between threats which are made overtly, and those which are covert. However, I think further work on covert threats may focus on this subtler way of dividing things up.We might also note that the distinction between overt and covert threats is not one with particularly sharp boundaries.

Corasaniti, Nick and Maggie Habermanaug (2016, August 10). Trump Suggests Gun Owners Act Against Clinton. The New York Times, pp. A1.

Solan and Tiersma (2005) discuss the treatment of threats in a legal setting (Ch. 10).

Virginia v. Black 1538 U.S. 343, 359–60 (2003)

Thanks to Simone Gubler, and an anonymous referee from Erkenntnis, for helpful suggestion here.

These terms—‘acceptance’ and ‘presupposition’—are sometimes used interchangeably in this literature; I reserve ‘acceptance’ to refer to the neutral conception and ‘presupposition’ to refer to the psychological conception. I believe that my use corresponds with an ordinary conception of what it is to accept a rule.

The role of such information in modeling discourse is beginning to be acknowledged to a greater extent; see Camp (2018) for just one recent discussion of the different roles played by different classes of information in a conversation.

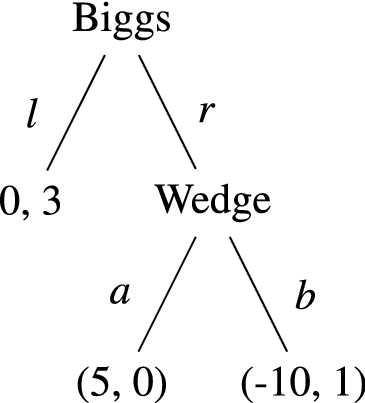

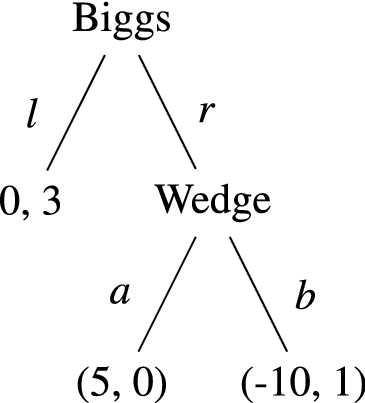

I have labeled the nodes ‘1’, ‘2’, etc.

See Gintis (2000: 7); of Little Monkey making an ‘incredible threat’.

In this case, this threat may not have a whole lot of credibility, as node 1 is Little Monkey’s lowest ranked outcome as well. This is why the appearance of conviction is often so important to threats (Sect. 4).

See Ross (2016) for some discussion of this notion.

We could represent this more completely with an additional set of moves for Wedge, but it is not necessary to do so.

Changing one another’s beliefs is part and parcel of being a human who can speak. For example, Wedge might just say “Hey Biggs, that pizza is terrible”, and then take it while they’re not looking.

There are other ways we could represent the state of Biggs’s being under threat. For example, it might be the case that we want to represent it in terms of Wedge placing a greater utility in punching Biggs (b) than doing nothing when Biggs goes for the pizza:

To say that this is the aim of a threat is not to suggest that a speaker must have a particular sort of communicative intention in order to threaten.

Even those who endorse convention-based accounts of speech acts accept that there is at least this sort of role played by intentions in eatablishing and maintaining conventions (Lewis 1969). See Armstrong (2016) and Geurts (2018) for some further discussion of the relationship between the conversational common ground and convention.

We might imagine that there is a difference between a threat that is credible and a threat that is merely apparently credible. My concern here is the appearance of credibility: whether it seems to an audience that the action threatened will have a utility to the threatener that makes it worthwhile to actually carry out.

Credible threats can be distinguished from the legal notion (mentioned earlier) of a true threat. True threats are threats that are issued with an intention to communicate a credible (criminal) intent; they may fail to be credible in the sense discussed here. The question of the role played by intent in a characterization of true threats has also been questioned (Crane and Paul 2006).

Richard Nixon called this the ‘Madman Theory’:

I want the North Vietnamese to believe I’ve reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to them that, ‘for God’s sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about Communism. We can’t restrain him when he’s angry—and he has his hand on the nuclear button’ and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace (Haldeman 1978: 122).

Solan and Tiersma (2005) note that threats and warnings are closely related to predictions.

This is in line with some of Parfit’s (1984) comments about the difference between threats and warnings (Chapter 1).

We might not think of ‘Rope Bridge’ as involving any game at all, if we think of games as interpersonal interactions. Or, more philosophically, we might think of agents as engaged in a game they play against the world (see Lewis 1978 for an articulation of basically this idea). The warning in ‘Rope Bridge’ gives information about this game; a warning constitutes an attempt to make a hearer aware of the rules of the game that they are playing against the world.

This is how the line between a threat and a warning may sometimes be blurred. It is often acknowledged, however, that performances of speech acts may instantiate distinctive, overlapping perlocutionary acts (see Searle 1969 for an early articulation of this idea).

Thanks to Dan Healey for some helpful conversation on this point. This is similar to the distinction between threats and warnings discussed by Fraser (1998), and later by Solan and Tiersma (2005). Fraser holds that the difference between threatening someone and warning someone about one’s own future action has to do with whether the subsequent action threatened is intentional or not.

Consider an example like a sign that says ‘Trespassers will be shot’. Is this a threat or a warning?

See, for instance, Fraser (1998). Fraser holds that a threat “involves conveying both the intention to perform an act that the addressee will view unfavourably and the intention to intimidate the addressee” (159).

See McGowan (2004)—especially pp. 94–97—for more discussion on this point.

References

Armstrong, J. (2016). The problem of lexical innovation. Linguistics and Philosophy, 39(2), 87–118.

Austin, J. L. (1963). How to do things with words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Camp, E. (2018). Insinuation, common ground, and the conversational record. In Daniel W. Harris, Daniel Fogal, & Matthew Moss (Eds.), New work on speech acts. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crane, P. T. (2006). True threats and the issue of intent. Virginia Law Review, 92(6), 1225–1277.

Franke, M. (2013). Game theoretic pragmatics. Philosophy Compass, 8(3), 269–284.

Fraser, B. (1998). Threatening revisited. Forensic Linguistics: International Journal for Speech, Language and Law, 5(2), 159–173.

Fricker, E. (2012). Stating and insinuating. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society Supplementary, 86(1), 61–94.

Geurts, B. (2018). Convention and common ground. Mind and Language, 33(2), 115–129.

Gintis, H. (2000). Game theory evolving. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Haldeman, H. R. (1978). The ends of power. New York: Times Books.

Harris, D. W., Fogal, D., & Moss, M. (2018). Speech acts: The contemporary theoretical landscape. In D. W. Harris, D. Fogal, & M. Moss (Eds.), New work on speech acts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haslanger, S. (2013). Social meaning and philosophical method. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 88, 16–37.

Khoo, J. forthcoming. Code words in political discourse. Philosophical Topics .

Klein, D. B., & O’Flaherty, B. (1993). A game-theoretic rendering of promises and threats. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 21, 295–314.

Langton, R. (1993). Speech acts and unspeakable acts. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 22(4), 293–330.

Lewis, D. (1969). Convention: A philosophical study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1978). Prisoners dilemma is a newcomb problem. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 8(3), 235–240.

Lewis, D. (1979). Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 8, 339–359.

Mao, L. R. (1994). Beyond politeness theory: Face revisited and renewed. Journal of Pragmatics, 21(5), 451–486.

McGowan, M. K. (2004). Conversational exercitives: Something else we do with our words. Linguistics and Philosophy, 27(1), 93–111.

McGowan, M. K. (2009). Oppressive speech. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 87(3), 389–407.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. London: Oxford University Press.

Pinker, S., Nowak, M., & Lee, J. (2008). The logic of indirect speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(3), 833–838.

Portner, P. (2007). Imperatives and modals. Natural Language Semantics, 15(4), 351–383.

Roberts, C. (2012). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics, 5(6), 1–69. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.5.6.

Ross, D. (2016). Game theory. In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/game-theory/: (Winter 2016 Edition).

Saul, J. (2017). Racial figleaves, the shifting boundaries of the permissible, and the rise of Donald Trump. Philosophical Topics, 45(2), 97–116.

Saul, J. (2018). Dogwhistles, political manipulation and philosophy of language. In D. W. Harris, D. Fogal, & M. Moss (Eds.), New work on speech acts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schauer, F. (2003). Intentions, conventions, and the first amendment: The case of cross-burning. The Supreme Court Review, 2003, 197–230.

Schelling, T. (1960/1980). The strategy of conflict, 2nd edn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Searle, J. (1969). Speech acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. R. (1976). A classification of illocutionary acts. Language in society, 5(1), 1–23.

Searle, J. R., & Vanderveken, D. (1985). Foundations of illocutionary logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shakespeare, W. (1604). The tragedy of Hamlet, prince of Denmark (second quarto edition). The complete works of William Shakespeare. http://shakespeare.mit.edu/hamlet/full.html.

Skyrms, B. (2010). Signals: Evolution, learning, and information. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Solan, L. M., & Tiersma, P. M. (2005). Speaking of crime: The language of criminal justice. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1978). Assertion. In P. Cole (Ed.), Syntax and semantics 9: Pragmatics. New York: Academic Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1996). Knowledge, belief and counterfactual reasoning in games. Economics and Philosophy, 12(2), 133–163.

Stalnaker, R. (2002). Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25, 701–721.

Stanley, J. (2015). How propaganda works. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

van Benthem, J. (2011). Logical dynamics of information and interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Watts, R. J. (2003). Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to David Beaver, Josh Dever, and Hans Kamp for extensive feedback on several drafts of this paper. An earlier version of this paper was presented twice during a visit to the Arché Philosophical Research Centre in the summer of 2017. I would like to thank all of the participants at those presentations, in particular Derek Ball, Lisa Bastian, Josh Dever, Maegan Fairchild, Dan Healey, Poppy Mankowitz, Quentin Pharr, Ravi Thakral, Brian Weatherson, and Alex Yates for their questions, comments, and suggestions. I have also benefited from informal discussions of this paper with Simone Gubler, Megan Hyska, Amelia Kahn, Bronwyn Stippa, and Cassandra Woolwine, as well as from the feedback offered by several anonymous reviewers at Erkenntnis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schiller, H.I. Is that a Threat?. Erkenn 86, 1161–1183 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-019-00148-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-019-00148-9