Abstract

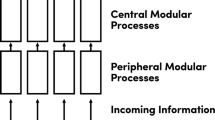

In this paper, I argue that a natural selection-based perspective gives reasons for thinking that the core of the ability to mindread cognitively complex mental states is subserved by a simulationist process—that is, that it relies on non-specialised mechanisms in the attributer’s cognitive architecture whose primary function is the generation of her own decisions and inferences. In more detail, I try to establish three conclusions. First, I try to make clearer what the dispute between simulationist and non-simulationist theories of mindreading fundamentally is about. Second, I try to make more precise an argument that is sometimes hinted at in support of the former: this ‘argument from simplicity’ suggests that, since natural selection disfavours building extra cognitive systems where this can be avoided, simulationist theories of mindreading are more in line with natural selection than their competitors. As stated, though, this argument overlooks the fact that building extra cognitive systems can also yield benefits: in particular, it can allow for the parallel processing of multiple problems and it makes for the existence of backups for important elements of the organism’s mind. I therefore try to make this argument more precise by investigating whether these benefits also apply to the present case—and conclude negatively. My third aim in this paper is to use this discussion of mindreading as a means for exploring the promises and difficulties of evolutionary arguments in philosophy and psychology more generally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Three things are worth noting about this classification schema. Firstly, there is a type of theory—the ‘Rationality Theory’—that is neither information-rich, nor information-poor; however, since it is no longer seen to be a credible contender in this debate (see e.g. Nichols and Stich 2003, pp. 142–148; Goldman 2006, Chap. 3), it will not be considered further here. Second, the term ‘theory–theory’ is sometimes used synonymously with that of ‘information-rich mindreading’ (e.g. in Nichols and Stich 2003, p. 102); this, though, seems to be merely a terminological issue of little importance. Finally, all of these theories operate at Marr’s ‘computational’ level of the cognitive hierarchy: they do not actually describe the algorithms used by the cognitive system or the neural realisation of these algorithms, but only the problems they have to solve (a point that will become important again below—see especially note 12); see also Nichols and Stich (2003, pp. 10–11, 209–210).

The ‘theory–theory’ and the ‘modularity theory’ are distinguished by their take on what this ‘extra stuff’ is (e.g. how the extra information being acquired, stored and processed, or what the nature of the specialised cognitive mechanisms is). Since this is not so important here, however, I shall not discuss it further.

Note that the mindreading procedure sketched in Fig. 1 might have to be performed more than once in any one application of the system (see also Gordon 1986; Goldman 2006, pp. 183–185). Note also that—to avoid terminological complications—the processor is to be seen as doing more than merely repeating the initially generated mental states.

This also gains strength from the recent popularity of hybrid theories of mindreading (as mentioned earlier). This popularity corroborates the fact that the two components of the mindreading system are not so intertwined that a separate discussion of them is impossible.

An objection that is sometimes raised to this argument claims that the above is the reverse of the true chronology: that is, it is argued that the evolution of our belief/desire psychology was actually driven by the evolution of our mindreading abilities (see e.g. Godfrey-Smith 2003; Sterelny 2003, Chap. 4). However, for two reasons, this objection is not very damaging to the present discussion. On the one hand, while it might be plausible that our minds received considerable sophistication due to our interactions with other agents, it is not clear that the basic components of our mind could have evolved entirely in this way (see also Godfrey-Smith 2003). On the other hand, even if this were a coherent possibility, the rest of the discussion would not be impacted all that much: instead of needing to ask if natural selection favours a dedicated mindreading system, we would then need to ask if it favours a dedicated inference and decision making system. This is bound to bring up many of the same issues that are raised in what follows.

Note that the form of the following argument is contrastive: the claim is not that building a dedicated mindreading processor is unlikely per se, but only that it is less likely than the competing, more parsimonious alternative (see also Sober and Wilson 1998). While it is true that this more parsimonious alternative is not costless (for example, a way has to be found to feed the beliefs and desires attributed to the target into the agent’s own reasoning mechanisms), it is still bound to be vastly cheaper overall than duplicating an entire practical and theoretical reasoning system.

I thank an anonymous referee for some useful remarks about this argument and the discussion concerning it.

I thank an anonymous referee for some useful remarks concerning this issue.

This is a well-known problem in Rational Choice Theory—see e.g. Savage (1954, pp. 25–26, 82–91).

This becomes especially obvious when it is noted that there is an indefinitely large set of possible future decision and inference problems. Unless the agent has some idea about which of these are actually relevant to her, indiscriminate ‘preparatory mindreading’ would completely swamp her cognitive system.

It is important to keep in mind here and in what follows that neural overlap is not the same as functional overlap: whether the latter is true for the mindreading processor and the agent’s own reasoning systems is a different question from whether the former is true. See also note 1.

Saxe et al. (2006) and Saxe and Powell (2006) might seem to suggest that there is no such neural overlap. However, when considering their studies more closely, it becomes clear that they do not show this: their findings are really only concerned with the mindreading generator, not the processor, and hence do not bear on the present issue.

This is accepted even by Saxe (2009).

References

Apperly, I., Back, E., Samson, D., & France, L. (2008). The cost of thinking about false beliefs: Evidence from adults’ performance on a non-inferential theory of mind task. Cognition, 106, 1093–1108.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2002). The extreme male-brain theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Science, 6, 248–254.

Bull, R., Phillips, L., & Conway, C. (2008). The role of control functions in mentalizing: Dual-task studies of theory of mind and executive function. Cognition, 107, 663–672.

Byrne, S., & Whiten, A. (Eds.). (1988). Machiavellian intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carruthers, P. (1996). Language, thought and consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carruthers, P. (2006). The architecture of the mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, A. (1992). The presence of a symbol. Connection Science, 4, 193–205.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1992). The psychological foundations of culture. In J. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind (pp. 19–136). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1986). The blind watchmaker. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Waal, F. (2008). Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 279–300.

Dennett, D. (1978). Brainstorms. Montgomery: Bradford.

Fodor, J. (1983). The modularity of mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fodor, J. (1992). A theory of the child’s theory of mind. Cognition, 44, 283–296.

Godfrey-Smith, P. (1996). Complexity and the function of mind in nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Godfrey-Smith, P. (2003). Untangling the evolution of mental representation. In A. Zilhao (Ed.), Cognition, evolution, and rationality: A cognitive science for the 21st century. London: Routledge.

Goldman, A. (2006). Simulating minds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gopnik, A., & Wellman, H. (1994). The theory-theory. In L. Hirschfeld & S. Gelman (Eds.), Mapping the mind (pp. 257–293). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gordon, R. (1986). Folk psychology as simulation. Mind and Language, 1, 158–172.

Harris, P. (1992). From simulation to folk psychology: The case for development. Mind and Language, 7, 120–144.

Klin, A., Volkmar, F., & Sparrow, S. (2008). Autistic social dysfunction: Some limitations of the theory of mind hypothesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 33, 861–876.

Leslie, A. (2000). ‘Theory of mind’ as a mechanism of selective attention. In M. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The new cognitive neurosciences (2nd ed., pp. 1235–1247). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nichols, S., & Stich, S. (2003). Mindreading. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Papineau, D. (2001). The evolution of means-end reasoning. In D. Walsh (Ed.), Naturalism, evolution, and mind (pp. 145–178). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pinker, S., & Bloom, P. (1990). Natural language and natural selection. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 13, 707–784.

Savage, L. (1954). Foundations of statistics. New York: John Wiley.

Saxe, R. (2009). The neural evidence for simulation is weaker than I think you think it is. Philosophical Studies, 144, 447–456.

Saxe, R., & Powell, L. (2006). It’s the thought that counts: Specific brain regions for one component of theory of mind. Psychological Science, 17, 692–698.

Saxe, R., Schulz, L., & Jiang, Y. (2006). Reading minds versus following rules: Dissociating theory of mind and executive control in the brain. Social Neuroscience, 1, 284–298.

Schulz, A. (forthcoming). Sober & Wilson’s evolutionary arguments for psychological altruism: A reassessment. Biology and Philosophy.

Sober, E. (1994). The adaptive advantage of learning and a priori prejudice. In From a biological point of view (pp. 50–70). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sober, E., & Wilson, D. S. (1998). Unto others: The evolution and psychology of unselfish behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stephens, C. (2001). When is it selectively advantageous to have true beliefs? Philosophical Studies, 105, 161–189.

Sterelny, K. (2003). Thought in a hostile world: The evolution of human cognition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Stich, S. (2007). Evolution, altruism and cognitive architecture: A critique of sober and wilson’s argument for psychological altruism. Biology and Philosophy, 22, 267–281.

Wicker, B., Keysers, C., Plailly, J., Royet, J.-P., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (2003). Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron, 40, 655–664.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Alvin Goldman, Elliott Sober, Larry Shapiro, Stephen Stich, Eric Margolis, and an anonymous referee of this journal for useful comments on previous versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schulz, A.W. Simulation, simplicity, and selection: an evolutionary perspective on high-level mindreading. Philos Stud 152, 271–285 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9476-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9476-5