Abstract

The question regarding how to characterize aesthetics has been revived with the publication of Bence Nanay’s Aesthetics as Philosophy of Perception. This paper takes seriously Dustin Stokes’ criticisms of Nanay’s book regarding Nanay’s inability to distinguish between ordinary expert visual tasks (e.g., sorting for sock color or ornithology) and aesthetic experience. Using empirical research on gist perception and its reliance on low-level features in visual experience, I develop a theory that distinguishes expert visual tasks and aesthetic experiences by differentiating two different kinds of distributed attention over properties. I argue that expert visual tasks are instances of property attribution in a mode of conscious attention, while aesthetics is a kind of distributed attention that significantly relies on the reiteration of gist-like lowlevel features. Gist, often referred to in visual science as “preattentive” mode, gives us a model to understand the perceptual processes that are specific to aesthetics. This comports with our common-sense definition of aesthetics as both distinguishable from ordinary expert visual tasks and an experience that makes prominent sensory aspects of visual experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

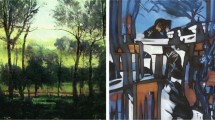

I am only relying on a verbal description of this scene instead of providing a visual, photographical representation of it, as the visual representation would be experienced by the reader as a photograph and thus as an instance of a represented image. This would have made the photograph of the shirts in the closet similar to the photographic representation of a painting. In other words, both photographs would likely be experienced aesthetically as they would equally be photographs, and no longer as stand-ins for the distinct actual experiences themselves.

The caveat of “some” is included as his last chapter characterizes the aesthetic experience of vicarious engagement with a fictional character, which is non-distributed attention relative to properties.

It is perhaps helpful to see this in symbolic terms: i = D & F; ii = D & D; iii = F & F; iv = F & D. This shows more clearly the relationship between i and iv. It is also worth repeating that ii is our usual distracted looking wherein we are not looking for anything in particular.

It should be remembered that Nanay’s definition of expert visual tasks (i. in the list above) is very distinct from ordinary visual perception, such as when we are looking for nothing in particular (ii. In the list above); and Stokes’ complaint is that it is expert visual tasks that collapse into aesthetics.

Nanay would say the difference is in the fact that in aesthetics it is the properties that are being scanned but that in expert visual tasks it is the objects being scanned, but remember also that Stokes makes a convincing argument that collapses those differences.

Though Sontag’s position does make a case for a formalism that relies on the experience of the non-representational aspects of shape, color, texture, etc., I am not arguing that formalism, in either art history or in Sontag’s position, is utterly equivalent with low-level features; but the relationship of formalism to low-level features does, it seems, serve as a source for further research.

This introduces a question often left unasked in philosophy: When we speak of “the aesthetic experience”, of whose experience of are we speaking?

Parrino died in 2005 from a motorcycle accident.

It is a further question how gist research might be applied to additional aesthetic experiences such as music or literature. My suspicion is that all valences of sensory input can be separated into low-level and high-level, and that all aesthetics involves stage perception similar to visual, which in turn would involve the provisional categorization of categories experienced temporally, but this is certainly an issue for further research.

In addition, scientists and mathematicians have developed models to explain how perception is neurologically reliant on low-level, sparse data (see Chariker et al. 2016; Young et al. 2019; Lian et al. 2019.). This research demonstrates that it is primarily the visual cortex that does the heavy lifting and not the information processed by the retina. The latter, instead, provides only minimal data to the midbrain structure called the lateral geniculate nucleus, which in turn passes it on to the visual cortex. That information in the LGN has been shown to be extremely sparse and low-level information (Ibid.). In short, the research all points to the fact that our perceptual processes are significantly constituted by low-level information.

This reliance on low-level information is not merely in a feedforward process, but significant amounts of low-level information function in a feedback loop (Herzog et al. 2015; Clark 2015). This is in contradistinction to the older models, originally promulgated by Hubel and Weiss in the 1950s, and then elaborated on by Marr in the 1970s, that saw the process as a more simplistic feed-forward one, wherein data from the world, experienced as low-level, was processed by the retina and then operated on by increasingly more complex structures and processes. But that is no longer thought to be the case. Various researchers in both vision science and empirical psychology have attested to this: “…low-level vision is not stereo- typical, hierarchical, feedforward, and retinotopic, but a complex recurrent process in which the neural representations of elements across large parts of the visual field interact” (Herzog et al. 2015).

References

Bar, M., Kassam, K. S., Ghuman, A. S., Boshyan, J., Schmid, A. M., Dale, A. M., et al. (2006). Top-down facilitation of visual recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 103, 449–454.

Bayne, T. (2016). Gist! Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 116, 107–126.

Bresnahan, A. (2017). Dance appreciation: The view from the audience. In D. Goldblatt, L. Brown, & S. Patridge (Eds.), Aesthetics: A reader in the philosophy of the arts (4th ed., pp. 347–350). New York: Routledge.

Buswell, G. T. (1935). How people look at pictures: A study of the psychology and perception in art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chariker, L., Shapley, R., & Young, L.-S. (2016). Orientation selectivity from very sparse LGN inputs in a comprehensive model of macaque V1 cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(49), 12368–12384.

Clark, A. (2015). Surfing uncertainty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dretske, F. (2015). Perception versus conception: The goldilocks test. In A. Demetriou & J. Zeimbekis (Eds.), The cognitive penetrability of perception: New philosophical perspectives (Vol. 15, pp. 163–173). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Epstein, R., & Kanwisher, N. (1998). A cortical representation of the local visual environment. Nature, 392(6676), 598–601.

Greene, M. R., & Oliva, A. (2009). Recognition of natural scenes from global properties: Seeing the forest without representing the trees. Cognitive Psychology, 58, 137–176.

Herzog, M. H., Thunell, E., & Ögmen, H. (2015). Putting low-level vision into global context: Why vision cannot be reduced to basic circuits. Vision Research, 126, 9–18.

Itti, L., & Koch, C. (2000). A saliency-based search mechanism for overt and covert shifts of visual attention. Vision Research, 40(10–12), 1489–1506.

Itti, L., & Koch, C. (2001). Computational modelling of visual attention. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(3), 194–203.

Itti, L., Koch, C., & Niebur, E. (1998). A model of saliency-based visual attention for rapid scene analysis. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 20(11), 1254–1259.

Koch, C., & Ullman, S. (1987). Shifts in selective visual attention: Towards the underlying neural circuitry. In L. M. Vaina (Ed.), Matters of intelligence: Conceptual structures in cognitive neuroscience (pp. 115–141). Dordrecht: Springer.

Lian, Y., et al. (2019). Towards a biologically plausible model of LGN-V1 pathways based on efficient coding. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 13, 13–24.

Locher, P. J. (2015). The aesthetic experience with visual art ‘at first glance’. In P. Bundgaard & F. Sternfelt (Eds.), Investigations into the phenomenology and the ontology of the work of art (pp. 75–88). Dordrecht: Springer, Cham.

Nanay, B. (2016). Aesthetics as philosophy of perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nodine, C. F., Locher, P. J., & Krupinski, E. A. (1993). The role of formal art training on perception and aesthetic judgment of art compositions. Leonardo, 26(3), 219–227.

Oliva, A. (2005). Gist of the scene. Neurobiology of Attention. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012375731-9/50045-8.

Oliva, A., & Torralba, A. (2006). Building the gist of a scene: The role of global image features in recognition. Progress in Brain Research, 155, 23–36.

Olshausen, B. A., Anderson, C. H., & Van Essen, D. C. (1993). A neurobiological model of visual attention and invariant pattern recognition based on dynamic routing of information. Journal of Neuroscience, 13(11), 4700–4719.

Parkhurst, D., Law, K., & Niebur, E. (2002). Modeling the role of salience in the allocation of overt visual attention. Vision Research, 42(1), 107–123.

Peacocke, C. (2008). Sensational properties: Theses to accept and theses to reject. Revue internationale de philosophie, 1, 7–24.

Pihko, E., Virtanen, A., Saarinen, V. M., Pannasch, S., Hirvenkari, L., Tossavainen, T., et al. (2011). Experiencing art: The influence of expertise and painting abstraction level. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 5, 94.

Prinz, J. (2013). Attention, atomism, and the disunity of consciousness. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 86(1), 215–222.

Schnieder, B. (2006). Attributing properties. American Philosophical Quarterly, 43(4), 315–328.

Schwabe, K., Menzel, C., Mullin, C., Wagemans, J., & Redies, C. (2018). Gist perception of image composition in abstract artworks. Perception, 9(3), 1–25.

Sibley, F. (1959). Aesthetic concepts. The Philosophical Review, 68(4), 421–450.

Siegel, S. (2006). Which properties are represented in perception. Perceptual experience, 1, 481–503.

Srinivasan, P., Srinivasan, N., Lohani, M., & Baijal, S. (2009). Focused and distributed attention. Progress in Brain Research, 176, 87–100.

Stokes, D. (2016). Aesthetics as philosophy of perception. Review of Aesthetics as Philosophy of Perception, by Bence Nanay. Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, 2016.08.10. Retrieved December 29, 2018 from https://ndpr.nd.edu/news/aesthetics-as-philosophy-of-perception/.

Tatler, B. W., Baddeley, R. J., & Gilchrist, I. D. (2005). Visual correlates of fixation selection: Effects of scale and time. Vision Research, 45(5), 643–659.

Wollheim, R. (1980). Art and objects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yarbus, A. L. (1967). Eye movements during perception of complex objects. In A. L. Yarbus (Ed.), Eye movements and vision (pp. 171–211). Boston, MA: Springer.

Young, L. S., Tao, L., Shelley, M., Shapley, R., Rangan, A., & McLaughlin, D. W. (2019). The evolution of large-scale modeling of monkey primary visual cortex, V1: Steps towards understanding cortical function. Communications in Mathematical Sciences, 17(5), 1387–1406.

Zangemeister, W. H., Sherman, K., & Stark, L. (1995). Evidence for a global scanpath strategy in viewing abstract compared with realistic images. Neuropsychologia, 33(8), 1009–1025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shottenkirk, D. A Tale of Two Reds. Erkenn 88, 289–307 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00351-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00351-z