Abstract

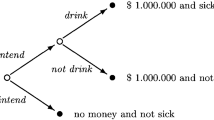

In this paper I present an underappreciated puzzle about intention. The puzzle is analogous to the famous Preface Paradox for belief, and arises for any theory according to which intentions are all or nothing states governed by two popular and plausible rational norms. It shows that at least one of these three assumptions must be substantially revised, and thus that many standard views about intention cannot be true. I consider two general strategies for responding to the puzzle. The more conservative approach retains the assumption that intentions are all or nothing states, and attempts to marshal independent arguments for modifying one of the two puzzle-generating norms. I briefly discuss this line of response and conclude that there is prima facie reason to reject the more commonly defended of the two, the Consistency norm, which requires a particular relationship between one’s intentions and one’s beliefs about those intentions’ execution. I then explore a more radical approach: a solution that parallels the well-known partial belief response to the Preface Paradox. According to this solution, the puzzle about intention ultimately derives from the mistaken thought that the paradigmatic conclusions of deliberation are fully committed states of intention. Instead, I suggest that what we call intentions, and think of as all or nothing states, may in fact often be only partially committed states, which I call states of inclination, and which must be governed by slightly different norms. In addition to showing that my theory of inclination may give us a motivated way out of the puzzle, I provide independent arguments for thinking that we have such mental states, and I say what I can about their nature and the norms that regulate them. These arguments do not depend on the viability of the more radical response to the puzzle. They purport to show that inclinations are psychologically real, and that countenancing them is necessary for vindicating plausible descriptive and normative truths about mental phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Harman (1976) is one important precursor. Bratman’s influence on the field makes him a natural focal point. For one illustrative example of how widely Bratman’s theory has been applied, see Shapiro (2011), who argues that the puzzling nature of legality should be understood in terms of the planning theory of intention.

In my formulation, the rational requirement operator takes “wide scope”, meaning that it ranges over the whole conditional. This ensures that we cannot detach a requirement to not believe that you will fail to A from the mere fact that you actually intend to A; it may be that you should instead give up the intention. See Broome (1999, 2007), and (Author Paper) for my take on the relevant debate, and for further references.

Bratman (1984: 383): “But given my knowledge that I cannot hit both targets, these two intentions fail to be strongly consistent. Having them would involve me in a criticizable form of irrationality.”

Wedgwood (2011: 301) defends a similar principle that connects intention to high degree of confidence in one’s execution of the intention. An interesting and relevant case of contention is Holton (2009: 51), who rejects stronger consistency norms in favor of the claim that intentions are rationally connected to partial belief.

For influential cognitivist accounts see Audi (1973), Davis (1984), Harman (1976, 1986), Velleman (1989, 2000), Setiya (2008). For an excellent discussion of intention, belief, and intentional action, see Mele (1992: Chapter 8). For an early skeptical discussion of the cognitivist thesis see Davidson’s ‘Intending’ (reprinted in 2006: Chapter 6, 128–132).

Jay Wallace (2001) is sometimes classified as a cognitivist, but this is misleading, since he only endorses the view that intending to A involves believing that it is possible that one A’s. As Bratman (2009: 34) notes, this claim is too weak to derive norms of consistency on intention. Mele (1989: 105) endorses at least the prima facie plausibility of the related view that “believing that one’s chances of A-ing are slim is incompatible with intending to A.” See also Mele (1992: Chapter 8).

You might be tempted to reject unrestricted requirements of belief consistency. But you may still accept more restricted versions, versions that prohibit not all inconsistencies in belief, but only those that are manifest to the believer, or those that the believer is in a position to observe without doing much epistemic work. At least many cases in which I intend to A will be cases in which, according to the cognitivist, I know, or am in a position to know, that I believe that I will A. In some such cases a belief that I will not A would surely be salient and thus trigger the more restricted prohibition.

For other sympathetic discussions of agglomerativity see Velleman (2007), who argues that only the cognitivist can properly motivate it; Zhu (2010), who defends the principle for “executively competitive” intentions; and Wedgwood (2011), who appears committed to endorsing it. For skepticism see McCann (1986). For an early rejection of the analogue for belief see Kyburg (1961).

Notice that even what we normally refer to as an individual intention may really amount to, or entail commitment to, a larger set of intentions. For instance, what we call Holmes’s intention to procure more of his seven per cent solution may really amount to, or involve implicit or explicit commitment to, a set of intended steps to such procurement. If this is right, then we typically have, or are rationally committed to having, far more intentions than we recognize immediately in introspection, and the paradox appears even more troubling. Of course it is an arbitrary convenience to restrict the puzzle’s description to an agent’s plans for the present month.

Another possibility: we submit that, contra our supposition, the mental states in question must be irrational. Yaffe (2010) takes this approach to Video Game, distinguishing between attitudinal and causal rationality, and claiming that Holmes is attitudinally, but not causally, irrational. I deny that there is any important sense in which Holmes is irrational. But I will not take up this particular dispute, since Bratman and other defenders of the norms are not committed to Yaffe’s approach, and since a sensitive discussion of it would take us far afield.

I’ll mention a further argument to this effect, which I owe to {…}. Imagine that Holmes is well attuned to the distinction between intending and endeavoring. Suppose further that Holmes has ample evidence that he typically falls short of executing all of his intentions for any given month. However, he has no evidence that he normally fails to execute all of his endeavorings. Then his belief that he will not execute the conjunction of plans will be rational only if the plans are intentions. In other words, if we grant that Holmes could have such a belief, and that such a belief could be rational, we must allow that the states in question are intentions.

Ordinary speakers are far more likely to balk at this than at the parallel claim about Holmes (the claim that he isn’t actually intending to hit target one, but only endeavoring or trying). Recall again that Bratman (1987) has influentially argued against stronger versions of Consistency by appealing to a case in which, on his telling, he intends to return a book to the library while also knowing that he often forgets to stop. (The thought being that this case and others like it motivate rejecting the view that rationality requires affirmatively believing that you will x, given that you intend to x.) More general considerations about the prevalence of forgetting bolster my contention that Holmes is rational in believing that he will not execute his overall plan, and explain why Bratman’s intuition about the library case can, with the help of Agglomerativity, lead to my conclusion about Sherlock’s Calendar.

Wedgwood (2011: 302) briefly notices something like the conflict that generates my puzzle, and endorses the view that “…one’s intentions should not be such that one has a high conditional probability that if one has precisely those intentions, one will not execute all of one’s intentions.” He then observes the parallel to the Preface Paradox in a footnote, endorses a “partial belief” strategy for responding to the Preface, but dismisses the notion of degrees of intention. In conversation Wedgwood has recognized the force of the Calendar Paradox, though he has not committed to any particular solution.

I suspect that in some informal treatments of the argument premise 9 is assumed to follow from 6 and 8. But this is a mistake. From P(A) and P(B) we cannot conclude P(A and B). A babysitter may be permitted give a child ice cream, and permitted to give the child candy, but not permitted to give the child ice cream and candy. Nonetheless, P(A) and P(B) may give us evidence that P(A and B). If there is no countervailing evidence, we are justified in drawing the inference. And the only reason to think 9 false is that it is incompatible with Consistency. This is what the argument is designed to illustrate.

As before, I represent this as a further premise rather than as a conclusion from 4 to 5, since from P(A) and P(B) we cannot always conclude P(A and B). Again the premise is warranted, since the only salient objection to it is based on the Consistency principle that’s at issue.

The case is adapted from Donnellan (1968).

Harman (1976) is an illustrative case of this conflict of intuitions, since his picture of intention requires both that it involve belief, and that it be sensitive to pressure for greater explanatory coherence. The upshot of my puzzle is that these normative conditions conflict: the more coherent and encompassing a plan we have for the future, the more rational it is to believe that it will not come to fruition.

{…} first suggested this to me.

This wariness can and should sometimes be defeated by substantive argument, of course.

This line of thought is presented and refined in a fascinating way in Easwaran (2015). See also Jeffrey (1970) and Foley (1993) for divergent conceptions of the connections between degrees of belief and the classical notion of full belief. For present purposes it isn’t important whether the partial belief strategy for addressing the Preface Paradox involves the eliminativist claim that there are no outright beliefs, or the Lockean claim that outright beliefs are just those degrees of belief that exceed a certain threshold of confidence.

I have struggled with the choice of a term of art for this state. ‘Being inclined’ has the virtue of being the canonical locution in English for the expression of partial intentions, as in ‘I’m inclined to come to dinner, but don’t count me in yet’. But ‘inclination’ is also famously used, in English translations of Kant, as a synonym for a certain kind of desire (see Kant 1997). Another option is ‘leaning towards’; unfortunately it is odd to say that one can lean towards an action and its negation equally, but one can be so inclined.

Strictly speaking, I take the aim to be something more normatively loaded, like the formation of rational aims.

I say paradigmatically because I don’t want to rule out the possibility of unconscious intentions, or intentions that come about via non-deliberative processes. Of course desires may also be reflectively or deliberatively endorsed, a la Frankfurt (1971). The point is just that this is not a paradigmatic feature of desire, whereas it is a paradigmatic feature of intention.

I strongly desire to buy a bottle of mezcal after I finish writing this section. But I know that the only way to do that, since it is after nine p.m., is to drive out of the state of Connecticut. I may rationally lack a desire to take that drive. But suppose I am highly inclined to buy the mezcal after I finish writing. Then it would be irrational to fail to be inclined to take the drive. This argument is really just an aperitif. We should expect a full account of the norms on partial intentions to do a great deal to distinguish them from desires, and to provide a more precise elaboration of their distinctive psychological role.

It is likely that a similar argument also tells against the first suggestion. Dispositions to intend are at least sometimes morally assessable, but the principles governing these assessments will be complex, and will reflect the fact that the category of dispositions to intend includes states with very different natures.

A referee evocatively objects: “To be wholeheartedly reckless might have a splendid boldness that is missing from timid, half-hearted recklessness.” This is true, but it doesn’t follow that the splendid boldness makes the wholehearted recklessness better overall: it may be better in one respect but worse in others, as we will presumably say of cases in which the recklessness is especially severe. Perhaps there are cases in which wholehearted recklessness is better overall than timid recklessness. My principle allows for this with the “other things being equal” clause.

I believe we must also consider the rationality of Holmes’s credences in evaluating his overall culpability. I omit discussion of this controversial qualification for the sake of simplicity.

Some readers will think this argument is too quick. Why not say that Holmes’ inclination to steal the costume is part of his plan to get a costume, or part of his plan for doing something on Halloween, for which he has envisioned alternative means? The answer is simply that this needn’t be the case. Holmes can be so inclined without having envisioned any alternative means to either of these ends.

Here again we should remind ourselves that there could be different kinds of partial intentions and thus different legitimate explanatory projects that are in some sense connected.

“Present-directed intentions” present their own difficulties, which I cannot address here.

See the striking results in Knobe (2003).

Something like this theory is suggested briefly in Kolodny (2008): “These similarities encourage the following suspicion. If we cut the mind at its joints, we find only ‘aimings’. Often, as when one has faith in one’s abilities and the world’s cooperation, one’s aiming is accompanied by the expectation that one will succeed. But, other times, when one lacks such faith, one’s aiming is not. Of course, we might reserve the word, ‘intention’, for aimings of the former sort. But then Confidence would be a merely linguistic thesis. Whether or not it would find support in ordinary usage, it would seem of limited philosophical interest.” Notice that Kolodny is talking only about the dimension of “expectation”, or belief in success, while I have also been concerned with degree of commitment to the act in question.

References

Adams, F. (1986). Intention and intentional action: The simple view. Mind and Language, 1, 281–301.

Audi, R. (1973). Intending. The Journal of Philosophy, 70(13), 387–403.

Bratman, M. (1981). Intention and means-end reasoning. The Philosophical Review, 90(2), 252–265.

Bratman, M. (1984). Two faces of intention. The Philosophical Review, 93, 375–405.

Bratman, M. (1987). Intention, plans, and practical reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bratman, M. (2009). Intention, belief, theoretical, practical. In S. Robertson (Ed.), Spheres of reason: New essays on the philosophy of normativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Broome, J. (1999). Normative requirements. Ratio, 12(4), 398–419.

Broome, J. (2007). Wide or narrow scope? Mind, 116(462), 359–370.

Davidson, D. (2006). Intending. In E. Lepore & K. Ludwig (Eds.), The essential Davidson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davis, W. (1984). A causal theory of intending. American Philosophical Quarterly, 21(1), 43–54.

Donnellan, K. (1968). Putting humpty dumpty together again. The Philosophical Review, 2, 203–215.

Easwaran, K. (2015). Dr. Truthlove, or how i learned to stop worrying and love Bayesian probabilities. Nous (forthcoming).

Foley, R. (1993). Working without a net: A study of egocentric epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frankfurt, H. (1971). Freedom of the will and the concept of a person. The Journal of Philosophy, 68(1), 5–20.

Harman, G. (1976). Practical reasoning. Review of Metaphysics, 29, 431–463.

Harman, G. (1986). Change in view. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Holton, R. (2008). Partial belief, partial intention. Mind, 117(465), 27–58.

Holton, R. (2009). Willing, wanting, waiting. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jeffrey, R. (1970). Dracula meets Wolfman: Acceptance vs. partial belief. In M. Swain (Ed.), Induction, acceptance, and rational belief. New York: Humanities Press.

Kant, I. (1997). Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals. Mary Gregor, translator. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Knobe, J. (2003). Intentional action and side-effects in ordinary language. Analysis, 63, 190–193.

Kolodny, N. (2008). The myth of practical consistency. European Journal of Philosophy, 16(3), 366–402.

Kyburg, H. (1961). Probability and the logic of rational belief. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Makinson, D. C. (1965). The paradox of the preface. Analysis, 25, 205–207.

McCann, H. (1986). Rationality and the range of intention. In P. French, T. Uehling, & H. Wettstein (Eds.), Midwest studies in philosophy (Vol. X, pp. 191–211). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McCann, H. (1991). Settled objectives and rational constraints. American Philosophical Quarterly, 28(1), 25–36.

Mele, A. (1989). She intends to try. Philosophical Studies, 55(1), 101–106.

Mele, A. (1992). Springs of action: Understanding intentional behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ross, J. (2009). How to be a cognitivist about practical reason. In Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics (Vol. 4). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Setiya, K. (2008). Cognitivism about instrumental reason. Ethics, 117(4), 649–673.

Shapiro, S. (2011). Legality. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Velleman, D. (1989). Practical reflection. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Velleman, D. (2007). What good is a will? In A. Leist (Ed.), Action in context (pp. 193–215). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Wallace, J. (2001). Normativity, commitment, and instrumental reason. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1(4), 1–26.

Wedgwood, R. (2011). Instrumental rationality. In Shafer-Landau, R. (Ed.) Oxford studies in metaethics (Vol. 6, pp 280–309). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yaffe, G. (2004). Trying, intending, and attempted crimes. Philosophical Topics, 32(1/2), 505–531.

Yaffe, G. (2010). Attempts: In the philosophy of action and the criminal law. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zhu, J. (2010). On the principle of intention agglomeration. Synthese, 175, 89–99.

Acknowledgments

For helpful discussion, I am grateful to Zed Adams, Alexis Burgess, Kenny Easwaran, Jay Elliott, Nathan Gadd, Dustin Locke, Rachel McKinney, Eliot Michaelson, Shyam Nair, David Plunkett, Jacob Ross, Mark Schroeder, Scott Shapiro, Gary Watson, Ralph Wedgwood, Joel Velasco, the Coalition of LA Philosophers, and especially Aness Webster and Gideon Yaffe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shpall, S. The Calendar Paradox. Philos Stud 173, 801–825 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-015-0520-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-015-0520-3