-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alexandra Anna Spalek, Kjell Johan Sæbø, To Finish in German and Mainland Scandinavian: Telicity and Incrementality, Journal of Semantics, Volume 36, Issue 2, May 2019, Pages 349–375, https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffz003

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Among the words that describe initial or final parts of events, words describing finishing stand out in a number of ways: in a language like English, there is a transitive verb which is singularly flexible regarding the type of event retrievable from the context; in a language like German, there is no verb but there is a verbal particle; in either case, there is a requirement of telicity and there is a requirement of theme incrementality. The present paper documents these facts and offers an analysis of the verbal particle.

1 INTRODUCTION

Aspectual verbs like begin or finish, which take verbal complements, as in (1a) or (2a), but can also take nominal complements, as in (1b) or (2b), have been a subject of attention in formal lexical semantics over some twenty years.1

(1)

Before you begin making the cake, heat your oven to 350 degrees and grease and flour a 9 inch round cake pan.

Now begin the cake by sifting the flour, salt and spices into a large mixing bowl, lifting the sieve up high to give the flour a good airing.

(2)

If your child likes to turn pages before you finish reading the page, that is okay.

By the time I had deciphered a sentence, my classmates had finished the page.

The general tendency since Pustejovsky (1995) has been to take these verbs to instantiate logical metonymy and to motivate methods of lexical coercion, and particularly work by Asher (2011) is influential, if not uncontroversial: Egg (2003) and Piñango & Deo (2016) advance alternative approaches.

A question which has not been at the center of attention is whether there are significant differences in how freely aspectual verbs can take nominal arguments; another is whether the pattern seen in (1) and (2) is cross-linguistically stable. Judging by the literature, the answer to the former question would seem to be negative, while the answer to the second question would seem to be affirmative. One objective of this paper is to demonstrate that on the contrary, there are clear and telling differences, intra- and interlinguistically; in particular, between finish and other aspectual verbs in English and between a language like English and a language like German regarding the expression of finishing.

Thus one English verb stands out as supremely flexible: finish. None other shares its ability to combine with virtually any referential term and to describe the relevant phase (here the final phase) of virtually any type of event, as long as it is telic and the referent of the referential term is its incremental theme. The verb begin, for one, is far more constrained, as indicated by (3) versus (4).

(3) She already had her horse unsaddled and had begun to groom her. […] Jennifer finished her horse and turned her into the nearby pasture.

(4) Grabbing a brush from the tack room, she began grooming her horse.Her father joined her and began #(grooming/to groom/on) Goliath.

Cross-linguistically, though English is not alone in allowing aspectual verbs to combine with referential DPs (thus finish has counterparts in, say, Spanish (acabar) or Polish (zakończyć)), in German, say, the options are more restricted. In particular, the closest counterpart to finish as a transitive verb is not a verb but a verbal particle or an adjective, as witnessed by the translations in (5):

(5) As soon as you finish the window, it looks dirty again.

Sobald Sie das Fenster fertig geputzt haben, …as soon you the window fertig cleaned have, …

Sobald Sie mit dem Fenster fertig sind, as soon you with the window fertig are,

Sobald das Fenster fertig ist, …as soon the window fertig is, …

We will first, in section 2, survey some facts which set finish apart from other aspectual verbs. In section 3, we consider the corresponding expressions in German and in Mainland Scandinavian, concentrating particularly on verbal particles and showing that, like transitive finish, they require forms of telicity and theme incrementality, and in section 4, we provide an analysis where these requirements are built in. Section 5 brings a conclusion and an outlook.

2 CHARACTERISTICS OF FINISH

Aspectual verbs like begin, continue, end, finish or start have in common that they exhibit so-called complement coercion: beside a canonical case where they take a verbal (infinitival or participial) or an event-nominal complement, there is a non-canonical case where they take a nominal complement which denotes an individual. The canonical case is illustrated in (1a), (2a), (6), and (7).

(6) Slowly, she ended the kiss and pulled away.

(7) The salesman had almost finished selling the car to the young man …

2.1 Flexibility

Regarding their ability to take a nominal argument, there are major differences among the five verbs mentioned above, in terms of what nominals they combine with and in terms of the range of interpretations of the resulting combinations. While begin, continue, end and start are rather restricted, making the relevant construction seem ‘semi-productive’ (Lapata & Lascarides, 2003, 262), finish is much more flexible.

There are rather narrow limits to what activity can be understood when begin or start has an individual-denoting complement. Broadly, it should be an activity of production, as in (1-b), or of consumption, as in (8).

(8) I wanted to skip my period so I finished the pack and started another.

(9) Kim began the tunnel.

(10) Yesterday I went to the side yard with a saw in my hand and began/started ?(on/pruning) the fig trees.

(11) The ironing board creaked … […] Annie finished the pillowcase and began/started ?(on/ironing) the nightgown.

By contrast, when finish takes a DP complement, without any preposition, the implied event can have a wide variety of contextual specifications. In fact, the negative evidence for begin or start, (10)–(11), turns positive once finish is at issue (see also (3) vs. (4)):

(12) We’ll start with pruning our young trees in the orchard. Once we’ve finished the orchard trees, …

(13) He finished the shirt and unplugged the iron.

(14) #He ended the shirt and unplugged the iron.

2.2 Proper or improper sub-event

Finish stands out in another respect too. Intuitively, begin, start, end and finish all zoom in on a part of some event, the first two on an initial part and the last two on a final part, and it is natural to assume that this part is a proper part. Thus in (2-a), finish reading the page clearly describes a proper final part of a reading of the page. However, this does not hold generally for finish: as shown by (15-a), a time adverbial with in can apply to a finish phrase and measure the duration of a full event of the (under)specified type from beginning to end. In fact, there is no evident truth conditional difference between (15-a) and the version without finish, (15-b).

(15)

Heart of Darkness is a short novel by Joseph Conrad. In fact, it is so short you could finish (reading) it in just a few hours.

Heart of Darkness is a short novel by Joseph Conrad. In fact, it is so short you could read it in just a few hours.

2.3 Telicity

There are indications that finish requires its verbal complement to be telic and that it is the only aspectual verb to do so. True, it can occur with predicates that are on the face of them atelic, but note, first, the strong difference between a case like (16-a) and the corresponding case with stop, which does not impose a telicity requirement (see Dowty 1979, 57):

(16)

As if he felt her presence, Kent finished shoveling snow.

As if he felt her presence, Kent stopped shoveling snow.

Since a reading where the predicate is implicitly quantized is often available, cases where finish is infelicitous because its verbal complement is atelic are not easy to find – but (the constructed) (17) may be a limiting case.4

(17) ?The sun will finish shining one day / on November 21 / around 3:30 pm.

While it may be fairly easy to read a temporal quantization into a verbal complement like shoveling snow, it is much more difficult when the complement is a mass or bare plural nominal; (16-a) thus contrasts with (16-c):

(16)

# As if he felt her presence, Kent finished snow.

2.4 Incrementality

According to Piñango & Deo (2016, 29), “the complement of begin, finish, etc. must be interpreted as an incremental theme argument of the implicit event”. There are different ways of defining theme incrementality, in terms of verbs or in terms of verb-specific theme roles, and more or less strict notions; roughly, that |$x$| is an incremental theme of a predicate |$P$| means that if |$P$| holds of |$x$| and an event |$e$|, parts of |$x$||$x^{\prime }$| correspond to parts of |$e$||$e^{\prime }$| and |$P$| holds of |$x^{\prime }$| and |$e^{\prime }$|.6

As far as we are able to determine, a suitably weak notion of incrementality is the one criterion, beside telicity, that must be met for finish|$x$| to make sense in a context. (18)–(20) offer evidence in support of this criterion.

(18) We’d just finished #(hoisting) the mainsail when the phone went.

(19) It was decided she should finish #(selling) the house before she underwent the surgery.

(20) If you are planting a tree, and you hear that the Messiah has come, first finish #(planting) the tree, then go and see.

The predicates that cannot be missing here are telic but the theme arguments are not incremental, rather the opposite, anti-incremental: a sail is not hoisted, a house is not sold, and a tree is not planted part by part but as a whole. The event may have distinct parts, but these parts do not qualify as hoistings, etc., of parts of the sail, etc., – if hoist holds of |$x$| and |$e$|, there are no proper parts |$x^{\prime }$| of |$x$| and |$e^{\prime }$| of |$e$| such that hoist holds of |$x^{\prime }$| and |$e^{\prime }$|.

The hypothesis that a criterion of incrementality is decisive is strengthened by the observation that felicity is restored if the object noun is plural or mass, or a collective term; such arguments can be incremental themes again.

(21) We used to sell 4.000 carcasses a day and now we don’t even sell 800.That said, we have now finished (selling) the stock we had built up.

Note that the theme incrementality constraint is only in force when finish has a (non-eventive) nominal complement, not when the complement is verbal, as (18)–(20) show: the sail, house, or tree must be an incremental theme with respect to the unexpressed verb, but it need not be an incremental theme with respect to the expressed verb.

(22) Incrementality constraint on finishfinish + DP is only felicitous if DP is an incremental theme,finish + |$[_{\textrm{VP}}$| V DP|$]$| can be felicitous otherwise too.

(23) …, the very second we had finished #(with) the boat.

2.5 Summary and outlook

We have seen that finish has three characteristics: (i) in its transitive use, it is singularly flexible as to the unspecified type of event; (ii) it does not necessarily describe proper parts of events of the (un)specified type; (iii) the (un)specified type of event must be telic. We have also seen that its transitive use involves a constraint of theme incrementality.

These facts are not reflected in the literature. To be sure, aspectual verbs, along with other verbs where one may expect a verbal complement but often encounters a nominal complement, like enjoy, have been extensively discussed since Pustejovsky (1991); among many others, Copestake & Briscoe (1995), Egg (2003), Asher (2011), de Swart (2011), and Piñango & Deo (2016) have contributed to the discussion. But the emphasis has been on how to unify the nominal complement use with the verbal complement use, and questions about what a particular verb may mean have been secondary. This is not to say that it cannot be done or that the need for discerning analyses is not acknowledged. Thus Lascarides & Copestake (1998), Fodor & Lepore (1998), Pustejovsky & Jezek (2008, 196ff.) and Asher (2011, 80ff.), among others, note that general (re-)interpretative mechanisms tend to over- or undergenerate interpretations. However, verb-by-verb analyses are as yet missing. As noted, the major focus has been on how to reconcile different sorts of arguments with one verb meaning, at the cost of explicating what each aspectual verb means and how it can, in the words of Asher (2011, 230), license only certain types of events.

One proposal, though, is more explicit than any other, namely, the one made by Piñango & Deo (2016), who define a lexical entry which is general both in regard to different aspectual verbs and in regard to different argument types. This entry includes a way to encode the incrementality constraint noted above, and we will return to it when we discuss ways to encode the corresponding constraint in connection with the German and Scandinavian data in section 4.

3 THE EXPRESSION OF FINISHING IN GERMAN AND NORWEGIAN

We now turn to the ways in which finishing is expressed in German or Mainland Scandinavian (MSc), arguing that what finish (and its counterparts in French, etc.) corresponds most closely to when it is a transitive verb is a verbal particle which primarily operates on transitive verbs (see Talmy 1991, 492). It is subject to the same constraints regarding telicity and theme incrementality. In section 4, we go on to develop an analysis of this verbal particle.

We introduce the principal ways in which the verb finish can be rendered in German and MSc, centering on Norwegian, in 3.1. Next, we take note of two properties of these means of expression, mirroring those observed for finish in 2.2 and 2.3. In 3.4, we focus on an incrementality constraint parallel to that noted for finish in 2.4, only that it concerns not a verb but a verbal particle, and in 3.5, we discuss some cases which may seem problematic in this regard.

3.1 To finish in Norwegian

Neither in German nor in MSc is it possible to render the English sentence (24) word by word. Any translation will somehow employ the root fertig (German), færdig (Danish), färdig (Swedish) or ferdig (Norwegian), but this is not a verb; it can either be a verbal particle or an adjective. (25) is a Norwegian translation with the verbal particle; (26) is a Norwegian translation with an adjective.

(24) He finished the shirt and unplugged the iron. (= (13))

(25) Han strauk ferdig skjorta og drog ut strykejernet.he ironed ferdig shirt-def and pulled out iron-def

(26) Han gjorde seg ferdig med (å stryke) skjorta og drog …he did reflferdig with (to iron) shirt-def and pulled …

Henceforth, we mainly focus on Norwegian; largely parallel facts can be stated about Danish, Swedish or German.

3.1.1 Alternatives to ferdig etc.

Strictly, the fact that there is no direct German or MSc translation of (24) is not conclusive evidence that there is no verb comparable to finish in German or MSc, only that in that context, no such verb can be used. And to be sure, there are the two German transitive verbs abschließen and beenden, and a MSc cognate of the former.7 But these are significantly more restricted regarding the range of nominal complements they can take (first and foremost event nominals) and (if the nominal is not an event nominal) the activities that are understood to come to an end. This allows us to maintain that the closest German or MSc counterpart to finish as a transitive verb with a non-eventive object is one or the other instantiation of the root fertig etc., as a verbal particle or as an adjective. In fact, support for considering the closest counterpart to be the verbal particle will come from a parallel shown in section 3.4 below, concerning incrementality.

In connection with verbs describing certain forms of consumption, the verbal particle ferdig can or should be replaced by opp ‘up’ or ut ‘out’. Here are two examples (the situation is roughly parallel in German):

(27) Når pipa er ny er det viktig å røyke opp hele tobakken.when pipe-def is new is it crucial to smoke up whole tobacco-def‘When the pipe is new, it is important to finish all the tobacco.’

(28) Det er sånn med meg at jeg må høre ut hele låta.it is so with me that I must hear out whole tune-def‘Me, I have to finish the tune once I’ve started listening.’

3.1.2 On the verbal particle ferdig

Phonologically, the particle and the verb can form one word, the primary stress falling on the first component, in German the particle, in Norwegian the verb; thus in (25) above, the second tone of the Norwegian particle is neutralized and the whole has the contour h*l-l-h. This tone neutralization is a symptom of secondary stress under compounding (Kristoffersen, 2000, 141).8

Depending on what type of event is referred to, it is sometimes possible to use a verb stem with a very wide and general meaning, in particular, gjøre ‘do’, which on its own is scarcely used with a concrete object, or ta ‘take’; see (29).

(29) Han gjorde ferdig skjorta og drog ut strykejernet.he did ferdig shirt-def and pulled out iron-def‘He finished the shirt and unplugged the iron.’

The verbal particle is largely restricted to transitive and unaccusative verbs (though there are some exceptions which we will come to in section 3.5).

3.1.3 On the adjectives ferdig

(26) showed that the root ferdig has an instantiation as an adjective. In fact, it has two: the adjective in (26) is predicated of the agent, but an adjective ferdig can also be predicated of a theme, as in (30-a). This case seems closely related to the adjectival passive of a verb with the verbal particle, as in (30-b).

(30)

Og bunadsskjorta er ferdig. and costume-shirt-def is ferdig ‘And the folk costume shirt is finished.’

Og bunadsskjorta er ferdig stroken. and costume-shirt-def is ferdig ironed ‘And the folk costume shirt is finished.’

(31) … ble … det gamle bygget #(revet) ferdig, og …… became … the old build-def #(demolished) ferdig, and …‘They finished demolishing the old building, and …’

3.2 Finality and agency

Recall from section 2.2 that the events described by finish and its arguments are not necessarily proper final parts of the complete events. The same goes for ferdig and its arguments, where the interval adverbial data can be replicated:

(32) Sildefiske, med ringnot. Fiska ferdig kvota på 8 dagar. herringfishing with ringnet fished ferdig quota-def on 8 days ‘Ring net herring fishing. We finished our quota in eight days.’

(33) Brudekket …blei ferdig støypt i natt.bridgedeck …was ferdig cast in night‘The bridge deck was finished last night.’

If the full event and its final sub-event do differ, the agent of the latter can itself be a part of the agent of the former, as suggested by (34): I am the agent of finishing the dress, but the agent of sewing it is the sum of you and me.

(34) Jag skall sy färdig den, så att du kan få gå hem. (Swedish)I shall sew färdig it so that you can get go home ‘I’ll finish it so you can go home.’

3.3 Telicity again

Recall from section 2.1 that finish cannot have an object in the form of a mass or bare plural nominal; such a nominal would block a telic interpretation. The same is true for the verbal particle in Norwegian, etc.: while the authentic (35-a) is fine, where the mass noun is in the definite form, the manipulated version (35-b) where it is in the indefinite form is clearly degraded.

(35)

Jeg tok det litt med ro, men måket ferdig snøen. I took it little with calm but shoveled ferdig snow-def ‘I took it easy but finished the snowshoveling.’

?Jeg tok det litt med ro, men måket ferdig snø.I took it little with calm but shoveled ferdig snow

Note, though, that the verb and its bare mass or plural complement can get a telic interpretation, if the latter is understood as a portion, a part of a routine; thus (36) is felicitous on an interpretation where skrelle poteter ‘peel potatoes’ passes tests for telicity, such as compatibility with på ‘in’ measure phrases.

(36) Han har juksa litt og skrelt ferdig poteter. he has cheated little and peeled ferdig potatoes ‘He has cheated a bit and peeled the potatoes already.’

3.4 Incrementality again

Recall from section 2.2 that finish as a verb with an individual-denoting theme puts another constraint on the type of event that the individual is understood to undergo, concerned with incrementality: if, say, the house is the theme, the understood type of event can be something that is done ‘part by part’, like building or cleaning the house, but not something like selling the house, which is, on the contrary, done ‘all at once’, ‘as a whole’.

(37-a-c) mirror the negative evidence of (18)–(20):

(37)

# sette ferdig storseilet hoist ferdig mainsail-def

# selge ferdig huset sell ferdig house-def

# plante ferdig treet plant ferdig tree-def

As soon as the theme is a sum or a collection, the same verbs are felicitous with ferdig: (38) contrasts with (37-c) and parallels the English data in (21). Like the noun stock in (21), the noun ‘hedge’, according to Rothstein (2010) a ‘homogeneous’ count noun, does not have atomic reference, i.e., a thing falling under it has parts in turn falling under it, for sub-events to be distributed over.

(38) Får se om vi planter ferdig hekken kanskje.get see if we plant ferdig hedge-def maybe‘We might plant the rest of the hedge.’

By contrast, cases like (39), with the adjective ferdig as predicated of an agent and with a nominal or an infinitival under the preposition med ‘with’, do not impose an incrementality constraint; thus (39) contrasts with (37-c) too:

(39) bli ferdig med (å plante) treet become ferdig with (to plant) tree-def ‘finish planting the tree’

3.5 Intransitive verbs

We have said that the particle ferdig and its cognates færdig, färdig and fertig predominantly operate on transitive verbs. This seems to be true, but we must also consider what it means when the particles do operate on intransitive verbs.

Two cases can be distinguished: (i) unergative verbs like flytte ‘move (to a new home)’, (ii) unaccusative verbs like modnes ‘mature’. The ‘incrementality criterion’ may seem to come under pressure in both cases. First, as unergative verbs have no theme argument, they can hardly have any incremental theme. Consider:

(40) I dag skal jeg flytte ferdig. Håper … jeg husker alle tinga … in day shall I move ferdig hope … I remember all things-def ‘I will finish moving today. Hope I don’t forget anything.’

Second, while unaccusatives do have a theme argument, incrementality may come under pressure, notably from so-called degree achievement verbs as in (41):

(41) Den modnes ferdig som hel klippfisk, og … It mature-reflferdig as whole cliff-fish, and … ‘Our salted and dried cod finishes maturing before it is cut.’

The only way we see to reconcile cases like this with a theme incrementality condition is to assume, following the lead of Kennedy (2012) and Piñango & Deo (2016, 387f.), that sometimes, and notably in the context of verbs of scalar change, what counts for theme incrementality is not the theme as such and its parts, but a scalar property in the theme argument, associated with the verb, and its measures. Specifically, in regard to (41), maturing sub-events may not map to parts of the cod, but they will map to measures of maturity in the cod. As for making a gratin, parts of the event will correspond to intervals in the degree to which the raw materials are a gratin.

We are aware, though, that this is yet far from an articulated analysis, and, like Piñango & Deo (2016, 387f.), who discuss a closely related issue, we leave the development of a more precise analysis for future work.11

4 THE ANALYSIS OF V + FERDIG

We now turn to analyzing the expressions of finishing that we have focused on in the last section, the verbal particle ferdig and its cognates, in formal terms. We will develop one analysis as our primary proposal, while also considering alternative ways to capture the facts we have surveyed and weighing their pros and cons. In a final step, we offer an analysis of the non-agentive adjective ferdig which builds on that of the verbal particle.

4.1 Basics

Basically, we conceive of the verbal particle ferdig as an expression that attaches to a verb that takes an internal argument – a transitive or unaccusative verb. We make the relatively standard assumption that a transitive verb has the same logical type as an unaccusative verb, |$e(vt)$|, it denotes a function from individuals (type |$e$|) to functions from eventualities (events or states, type |$v$|) to truth values. This means that the theme role is incorporated into the verb, while the agent role is introduced, if at all, by a separate Voice head above the VP. Aspect and Tense, assumed to close off the event variable, are introduced above VoiceP.

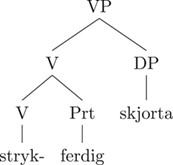

Concentrating on the VP, the LF we assume for ferdig is (42).12

(42) stryk- ferdig skjorta iron- ferdig shirt-def

(43) |$[\![$|ferdig|$]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,\lambda e$| …

4.2 Piñango & Deo (2016): presupposing incrementality

Piñango & Deo (2016) propose an analysis which unifies all uses of all English aspectual verbs, in particular the four cases which are illustrated in (44)–(47), in one general frame entry of the form (48) (|$\sqsubset $| is the proper-part relation).

(44) A challis hem finishes the shirt.

(45) He finished ironing the shirt.

(46) He finished the ironing.

(47) He finished the shirt.

(48) |$[\![\,$|verb|$]\!] = \lambda x \lambda y: \ $|struct-ind|$_f\!{_c}(x) \,. \ \exists f^{\prime } \,\left[\,f^{\prime }(y) \sqsubset _{\textrm{small-}}\right.$|_|$\left.\,f\!_c(x)\, \right]$|

(49) |$[\![\,$|finish|$\,]\!] = \lambda x \lambda y: \ $|struct-ind|$_f\!{_c}(x) \,. \ \exists f^{\prime } \,[\,f^{\prime }(y) \sqsubset _{\textrm{small-fin}} f\!_c(x)\,]$|

The presupposition struct-ind|$_f\!{_c}(x)$| is spelt out in (50):

(50) |$x$| is a structured individual wrt |$f$| iff (i) |$f(x)$| is an axis and (ii) for all two parts |$x^{\prime }$| and |$x^{\prime \prime }$| of |$x$|, |$x^{\prime } \sqsubseteq x^{\prime \prime } \rightarrow f(x^{\prime }) \sqsubseteq f(x^{\prime \prime })$|

A finish sentence thus means that one axis is a small final part of another, and one like (45) or (47) means that one event is a small final part of another; more exactly, the smallest event that the subject is an agent of is a small final part of, for (47), the event denoted by the verbal argument, for (45), the smallest event that the nominal argument is a theme of. Furthermore, the presupposition that this argument is a structured individual with respect to the inverse theme function, as defined in (50), implies that this argument must be interpreted as an incremental theme of the implicit event.

This theory is not directly applicable to the case of the verbal particle ferdig. In fact, some aspects of it may seem problematic even in relation to English. One is that the existence of |$f\!_c(x)$| is effectively presupposed, not (just) entailed. Thus a finish sentence will be undefined unless there is a complete event.

(51) The crew finished unloading the ship.

Note that this is not directly related to the problem with begin noted by Egg (2003, 164) and Asher (2011, 75), akin to the ‘imperfective paradox’, viz., that a begin sentence with a telic predicate should not entail that a full event exists; that can be solved by introducing a modal element in the definition, in analogy to modal theories of the progressive. For (51), however, the problem is that it should entail that there is a complete event, so the existence of |$f\!_c(x)$| should be a truth condition, not a definedness condition.

Second, if |$f\!_c$| is the inverse theme function, as it is in cases like (47), |$f\!_c(x)$| is not the event of which |$x$| is understood to be the theme in the context, but the event of which |$x$| is in fact the theme. The missing type of event is thus determined not by the context but by the world and time – once the context has determined that |$f\!_c$| maps an individual to the smallest event it is a theme of, the event |$f\!_c(x)$| and thus the type of it depends on what is in fact the case.

This may be thought to go against an argument from what is said in a context. Suppose you ask me whether I have finished the room and you have a specific event type in mind, say, vacuuming it. According to the definition of finish, I can answer affirmatively and truthfully although I have only dusted it, because all the definition cares about is what event the room has in fact been theme of. To be sure, there is a context dependency built into the function |$f_c$|, but that only concerns which function it is, not what value the function yields once the context has determined it to be the inverse theme function; after that, the value only depends on the room and the world and time.

As far as finish is concerned, it would also be necessary to constrain |$f\!_c(x)$| to events that are telic. This is not straightforward, though: Krifka (1998, 207) argues that it is impossible to distinguish telicity from atelicity by only looking at particular events; telicity is not a property of events but of event descriptions, or predicates. Therefore, it would seem necessary to take the event description into account and to make the analysis predicate-relative.

Finally, the requirement that the final sub-event be a small final sub-event must be removed, since, as we saw in section 2.2 (and again in section 3.2), the truth of a finish statement can be witnessed by a case where the event at issue is an improper sub-event of the complete event.

Returning to the applicability of this analysis to ferdig as a verbal particle, we may note that, for one thing, there is no way to express the content of (44) with ferdig; more importantly, what the verbal particle takes as an argument is neither an event nor an individual but the meaning of a (transitive) verb. One feature of the theory, however, merits careful consideration when the meaning is to be defined: the theme incrementality constraint is encoded as a definedness condition. At a general level, this feature can be mimicked in a continuation to the open-ended definition (43), repeated here:

(43) |$[\![$|ferdig|$]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,\lambda e$| …

(52) |$[\![$|ferdig|$]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,\lambda e \,:\, \ldots \forall \, e^{\prime } \!, w^{\prime }\ldots P_{w^{\prime }}(x)(e^{\prime })\ldots \ \,.\, \ \ldots $|

4.3 Building it into the word meaning

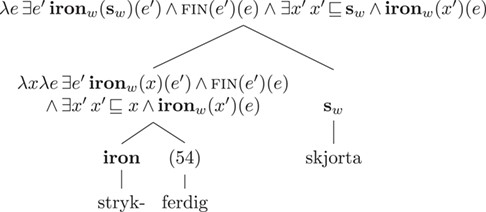

As a definition of the descriptive content of ferdig, (53) is a natural candidate:

(53) |$[\![$|ferdig|$\,]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,\lambda e \ \exists \, e^{\prime } \ P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) \ \wedge \ $|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e)$|

(54) |$[\![$|ferdig|$\,]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,\lambda e \ \exists \, e^{\prime } \ P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) \ \wedge \ $|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \, \wedge \, \exists x^{\prime } \ x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \, \wedge \, P_w(x^{\prime })(e)$|

More colloquially, (54) says that to |$P$|ferdig|$x$| is to |$P$| a part of |$x$| as a final part of |$P$|-ing |$x$|. For instance, ironing ferdig an item is not only doing a final part of ironing it but also ironing a part of it. We can illustrate the semantic composition by annotating the LF in (42) with denotations as in (55):

(55)

(54) shares one key feature with the analysis of the German verb aufessen ‘eat up’ proposed by Engelberg (2002, 396), who distinguishes two variants, one synonymous to essen ‘eat’ but the other presupposing a previous event of eating a part of the object and entailing an event of eating the rest of it. Some aspects of this analysis may be problematic, but the idea that auf-P, or fertig-P, entails an event of |$P$|-ing a part of |$x$| is, as we will try to show, a fruitful one.

4.3.1 The two constraints

We now turn to the two constraints on the verb and its eventual complement, V and DP in (42), evidenced by (35) and (37) in section 3.3, one concerned with telicity and the other with incrementality, as we are now in a position to make the relevant notions precise and to show that both constraints are in fact inherent in the definition (54). Specifically, ferdig turns out to be redundant if (i) V + DP is ‘anti-telic’ in the sense of having divisive reference or (ii) V is ‘anti-incremental’ wrt. DP, in a sense to be defined. Let us explain how.

Our first aim is to show that if the predicate V + DP has divisive reference, it turns out to denote the same set of events as the predicate [V ferdig] + DP. A simple definition of divisive reference for event properties is (56).13

(56) A property of events |$Q$| is divisive if and only if for all |$e$| and |$w$|,|$Q_w(e)\, \rightarrow \,\forall e^{\prime } \,[\, e^{\prime }\!\sqsubseteq e \rightarrow Q_w(e^{\prime }) \,]$|

Now we need to demonstrate that if the property of events |$\lambda w \lambda e P_w(x)(e)$| (for which we will also use the simplified notation |$P(x)$|) is divisive, then for all |$w$|, |$[\![$|ferdig|$\,]\!]^w(P)(x)$| is the same set of events as |$\lambda e P_w(x)(e)$|:

|$\lambda e \,\exists e^{\prime } \,P_w(x)(e^{\prime })\, \wedge \,$|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \wedge \exists x^{\prime } \,x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \wedge P_w(x^{\prime })(e) \ = \ \lambda e \,P_w(x)(e)$|

(57) |$\exists e^{\prime } \,P_w(x)(e^{\prime })\, \wedge \,$|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \wedge \exists x^{\prime } \,x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \wedge P_w(x^{\prime })(e) \ \Rightarrow \ P_w(x)(e)$|

|$\exists e^{\prime } P_w(x)(e^{\prime })\, \wedge \,$|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \wedge \exists x^{\prime } \,x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \wedge P_w(x^{\prime })(e) \\ \wedge [\,P_w(x)(e^{\prime })\, \rightarrow \,\forall e^{\prime \prime } \,[\, e^{\prime \prime }\!\sqsubseteq e^{\prime } \rightarrow P_w(x)(e^{\prime \prime }) \,]] \ \Rightarrow \ P_w(x)(e)$|

Our next task is to introduce the notion of ant-incrementality that seems to be relevant for the negative evidence in (37) in section 3.3 and to show that if the predicate V has this property with respect to its theme DP, V + DP turns out, again, to denote the same set of events as the predicate [V ferdig] + DP.

(58) A type |$s(e(vt))$| verb |$P$| is anti-incremental wrt. |$\!x$| iff for all |$e$| and |$w$|,|$P_w(x)(e)\, \rightarrow $| there are no |$x^{\prime } \!\sqsubset x$| and |$e^{\prime } \!\sqsubset e$| such that |$P_w(x^{\prime })(e^{\prime })$|

(59) A type |$s(e(vt))$| verb |$P$| is strictly incremental wrt. |$\!x$| iff for all |$e$| and |$w$|,|$P_w(x)(e)\, \rightarrow $| there is a bijection |$f$| from |$\{ \, x^{\prime } \!: x^{\prime }\!\sqsubseteq x \,\}$| to |$\{ \, e^{\prime } \!: e^{\prime }\!\sqsubseteq e \,\}$| s.t.|$\forall x^{\prime } \,[\, x^{\prime }\!\sqsubseteq x \rightarrow P_w(x^{\prime })(f(x^{\prime })) \,] \, \wedge \, \forall e^{\prime } \,[\, e^{\prime }\!\sqsubseteq e \rightarrow P_w(f^{-1}(e^{\prime }))(e^{\prime }) \,]$|

|$\lambda e \,\exists e^{\prime } \,P_w(x)(e^{\prime })\, \wedge \,$|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \wedge \exists x^{\prime } \,x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \wedge P_w(x^{\prime })(e) \ = \ \lambda e \,P_w(x)(e)$|

(57) |$\exists e^{\prime } \,P_w(x)(e^{\prime })\, \wedge \,$|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \wedge \exists x^{\prime } \,x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \wedge P_w(x^{\prime })(e) \ \Rightarrow \ P_w(x)(e)$|

One case remains: |$e$| is a proper part of |$e^{\prime }$|, but |$x^{\prime }$| is an improper part of |$x$|: |$x^{\prime } \!= x$|. Then the left side in (57) reduces to |$\exists e^{\prime } \,P_w(x)(e^{\prime })\, \wedge \,$|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \wedge P_w(x)(e)$|, where the right side in (57) is a conjunct, so the deduction is again trivially valid.

We have thus shown that for ferdig to make a semantic difference, V + DP must not be anti-telic in the sense of having divisive reference as defined in (56), and V must not be anti-incremental wrt. DP as defined in (58), and this is how we account for the facts evident in (60)–(62), where ferdig fails to make sense.

(60) … sortere (#ferdig) linser … sort (#ferdig) lentils ‘sort lentils’ (anti-telic, not anti-incremental)15

(61) … flytte (#ferdig) pasienten … move (#ferdig) patient-def ‘move the patient’ 16 (anti-incremental, not anti-telic)

(62) … skuve (#ferdig) ei kjerre … push (#ferdig) a cart ‘push a cart’ (anti-telic and anti-incremental)

(63) flytte ferdig pasientene

move ferdig patients-def

‘finish moving the patients’

4.3.2 Redundancy as a source of anomaly

To be sure, this way to explain that ferdig requires |$P(x)$| or |$P$| not to be anti-telic or anti-incremental rests on the premiss that redundancy results in infelicity or anomaly of the sort attested in (60)–(62), and this premiss is not self-evident. It may be more reasonable to expect redundancy to cause a pragmatic than a semantic infelicity, especially if one thinks of cases where, say, an adjective is superfluous because it modifies a hyponym, like unmarried bachelor.

Observe, however, that in the case under consideration here, a functor turns out to be redundant by virtue of its logical properties and those of its argument. Insofar, it would seem to have less in common with redundancies arising from particular lexical entailments (such as the case of unmarried bachelor) than with certain cases which have been argued to be responsible for semantic anomalies. One case in point is the infelicitous application of the English progressive to a stative verb, which Ogihara (2007, 406) attributes to the fact that under the analysis of Dowty (1986, 44), the operation is vacuous if the operand is stative. Other examples concern disjunctions where the first disjunct entails the second (Singh, 2008), objective propositions under subjective attitudes (Sæbø, 2009a), and vacuous binding in connection with verbs of having (Sæbø, 2009b).

This line of argument has a possible analogy in the notion of L-analyticity introduced by Gajewski (2002), analyticity rooted in logical constants or items reducible to logical constants, across all (occurrences of) non-logical constants: sentences that are trivial in virtue of their logical structure are ungrammatical in virtue of their triviality. In fact, Chierchia (2013, 42ff.) (who uses the term ‘G-triviality’ and applies it not only to contradictions and tautologies but also to necessary presupposition failures) cites the (anti-)telicity constraint imposed by ‘in’ and ‘for’ time adverbials as a case where this sort of triviality is or ought to be at stake. By analogy, cases of redundancy arising from items reducible to logical constants and logical properties of non-logical constants could be argued to cause semantic infelicity or anomaly in virtue of their vacuity. It is possible, then, to defend the position that the redundancy of ferdig in the context of an anti-telic or anti-incremental predicate is all that needs to be shown to account for the relevant negative facts, on the grounds that this is a case of ‘L-vacuity’: as defined in (54), ferdig is reduced to logical constants, and anti-telicity and -incrementality are logical properties cutting across large classes of predicates.

While we believe an appropriately strict notion of vacuity can eventually be defined, it is a broad and complex topic, not only as far as vacuity is concerned but also in regard to triviality (see, e.g., the critical discussion of L-analyticity in (Abrusán, 2014, 54ff.)), too broad and complex for us to pursue in this study. We would, therefore, like to briefly outline two alternative ways to account for the constraints against anti-telicity and anti-incrementality.

One possible move, analogous to a common way of capturing the constraint against (anti-)telicity with ‘in’ or ‘for’ time adverbials (see, e.g., (Krifka, 1998)), is to ascribe a presupposition to the verbal particle ferdig to the effect that

(i) |$P(x)$| is not anti-telic and

(ii) |$P$| is not anti-incremental wrt. |$\!x$|.

(64) |$[\![$|ferdig|$\,]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,: $|

|$ \, [ \exists \, e, w \ P_w(x)(e) \, \wedge \, \exists \, e^{\prime } \ e^{\prime } \sqsubseteq e \, \wedge \, \neg P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) ] \, \wedge $|

|$ \, [ \exists \, e, w \ P_w(x)(e) \, \wedge \, \exists \, x^{\prime }, e^{\prime } \ x^{\prime } \sqsubset x \, \wedge \, e^{\prime } \sqsubset e \, \wedge \, P_w(x^{\prime })(e^{\prime }) ] . \ $|

|$\lambda e \ \exists \, e^{\prime } \ P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) \ \wedge \ $|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \, \wedge \, \exists x^{\prime } \ x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \, \wedge \, P_w(x^{\prime })(e)$|

There is yet another option, however, a middle way between the two options described above: we can exploit the fact that ferdig is redundant in case |$P(x)$| is anti-telic or |$P$| is anti-incremental wrt. |$\!x$| by formulating a general presupposition that the meaning of [V ferdig] + DP is different from the meaning of [V DP]:

(65) |$[\![$|ferdig|$\,]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,:\, [ \lambda w \lambda e P_w(x)(e) ] \, \neq $|

|$[ \lambda w \lambda e \, \exists \, e^{\prime } \ P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) \ \wedge \ $|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \, \wedge \, \exists x^{\prime } \ x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \, \wedge \, P_w(x^{\prime })(e) ] . \ $|

|$\lambda e \ \exists \, e^{\prime } \ P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) \ \wedge \ $|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \, \wedge \, \exists x^{\prime } \ x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \, \wedge \, P_w(x^{\prime })(e)$|

The condition between: and. states just that: the left side of the inequality is the meaning of [V DP] and the right side is the meaning of [V ferdig] + DP. If |$P(x)$| is anti-telic or |$P$| is anti-incremental wrt. |$\!x$|, the presupposition fails because the left side equals the right side.

Under this amalgam analysis, ferdig belongs to a class of function-denoting items (the nature and extent of which would still need to be determined) whose values are only defined when the functions make a difference to their arguments. Since it ensures, case by case, that redundancy causes necessary presupposition failure and thus, under common assumptions, semantic anomaly, one can see it as a way to directly encode the narrow notion of vacuity discussed above.

While this move may ultimately turn out to be unnecessary, let us note that it makes clear why cases like (32), where the ferdig part of the fishing the quota event is understood to be an improper part, so that ferdig is in a certain sense redundant, are not felt to be in any way anomalous.

(32) Sildefiske, med ringnot. Fiska ferdig kvota på 8 dagar.

herringfishing with ringnet fished ferdig quota-def on 8 days

‘Ring net herring fishing. We finished our quota in eight days.’

The requirement that the meaning of the VP with ferdig not be the same as the meaning of the VP without it concerns general semantic properties of predicates across contexts; thus if, as in (32), what is said with ferdig in a context coincides with what would be said without it, this is not predicted to cause infelicity.19

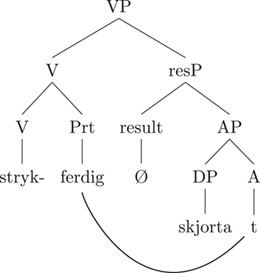

4.4 A resultative analysis?

Both our primary proposal (54) and the alternative analyses (64) and (65) are based on a logical form where ferdig is a sister to V, (42). This way to build the meaning of the VP has a possible alternative, which also merits consideration.

Let us suppose that the VP is really a resultative construction where ferdig is merged as an adjective but linearizes next to V, along the lines of Kratzer (2005). A resultative ‘small clause’ analysis (Ramchand & Svenonius, 2002) would be consistent with two facts: one, that cases like (66), where ferdig occurs to the right of the object, do occur, two, that (as noted in section 3.1, see (29)) the verb can be gjøre ‘do’, which is scarcely used with a concrete object, see (67). One way to represent a resultative analysis is shown in (68).

(66) Det tok fire timer å stryke duken ferdig.

it took four hours to iron tablecloth-defferdig

‘It took four hours to finish the tablecloth.’

(67) Det tok fire timer å gjøre #(ferdig) duken.

it took four hours to do #(ferdig) tablecloth-def

‘It took four hours to finish the tablecloth.’

(68) stryk- ferdig skjorta

iron- ferdig shirt-def

There are several counterarguments to this approach, however. First, one would expect intransitive verbs to occur in the construction, in analogy to cases like (69) (Hoekstra, 1988), but this expectation is not met.

(69) The clock ticked the baby awake.

(70)

Sonen skulle slå ferdig jordet med nytraktoren.

son-def should mow ferdig field-def with newtractor-def

‘The son was to finish (mowing) the field with the new tractor.'

# Sonen skulle køyre ferdig jordet med nytraktoren.

son-def should drive ferdig field-def with newtractor-def

Second, the problem remains that ferdig, interpreted in situ, lacks access to V, so again, there is no way to encode a constraint against anti-incrementality.

Third, one would expect the adjective/particle to agree with DP in number, but in fact, the evidence is equivocal: the uninflected form occurs more often than the plural form ferdige even when it linearizes to the right of a plural DP, and when it linearizes to the left, the plural form is scarcely possible (note that this cannot be tested in German, where predicative agreement is missing):

(71) Judith Aronsen har brodert begge dukene ferdig(e).

Judith Aronsen has embroidered both tablecloths ferdig

‘Judith Aronsen has finished (the embroidery on) both tablecloths.’

(72) Og nå skal jeg skrelle ferdig(*e) potetene.

and now shall I peel ferdig potatoes-def

‘And now I’m going to finish (peeling) the potatoes.’

(73)

Regnet vaska rein(e) de steinene som lå i overflata.

rain-def washed clean the stones that lay in surface-def

‘The rain washed the surface rocks clean.’

‘Regnet vaska de steinene som lå i overflata, rein*(e).

rain-def washed the stones that lay in surface-def clean

‘The rain washed the surface rocks clean.’

A remaining question is how to analyze the case exemplified in (66) or (67), where the DP intervenes between V and ferdig; this case would seem to be easier to handle with the analysis in (68) than with our analysis in (42). We have no definitive answer, but there are signs that this reordering is a PF interface phenomenon and a form of scrambling, sensitive to prosody and to information structure.20 Note, as a case in point, that the order object < particle is strongly dispreferred if the former is a new-information indefinite:

(74)

Vi trenger hjelp til å sparkle ferdig et rom.

we need help to to spackle ferdig a room

‘We need help to finish spackling a room.’

? Vi trenger hjelp til å sparkle et rom ferdig.

we need help to to spackle a room ferdig

We thus tentatively conclude that even in sentences like (66) and (71), ferdig is interpreted as a sister to V, as in our analysis (42).

4.5 Adjective ferdig

The adjective ferdig as it occurs in (75) or in (76) remains to be analyzed. The case is prima facie problematic because there is no verb. In order to reuse the analysis we gave in (54), we need to posit an implicit verb.

(75) Skjorta er ferdig.

shirt-def is ferdig

‘The shirt is finished.’

(76) (Dei sloga gjødsla … . Dei harva åkrane og … .) Når åkeren var ferdig og vêret lagleg, sådde …

when field-def was ferdig and weather-def agreeable sowed …

‘(They disked the manure … . They harrowed the fields and … .)

When the field was finished and the weather was good, they sowed …’

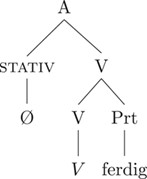

We would like to suggest that the adjective is built from the verbal particle defined in (54) and two covert building blocks: (i) a type |$e(vt)$| verb |$V$| as a free variable and (ii) a special ‘stativizer’ inspired by Kratzer (2000), defined in (77):

(77) |$[\![\,$|stativ|$\,]\!]^w = \lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \lambda s \ \exists e \ \textrm{result} (e)(s) \wedge P_w(x)(e)$|.

(78)

The theme-subject adjective ferdig is on this analysis an adjectival passive, elliptical but structurally like a case where V and the stativizer are articulated by a verb and past participle morphology, as in (30-b) in section 3.1.

This concludes our account of the word(s) expressing finishing in a language like Norwegian or German. We realize that there are loose ends in the account, in particular that the use of ferdig/fertig as an adjective with an agent subject, a preposition med/mit and a nominal or verbal complement, as in (26), has not been analyzed; pursuing this, though, would take us too far off our main course.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND OPEN ISSUES

In spite of all that has been written on aspectual verbs and how they and their complements of different sorts compose semantically, finish and its counterparts in languages like French or German have been underdescribed in three regards.

First, the particular freedom with which finish or French finir can compose with non-eventive nominal complements, as compared to other aspectual verbs like begin or commencer, has not been taken due account of. Second, what the transitive verb finish corresponds to in a language like German, where its closest counterpart is arguably a verbal particle, has not been systematically described. Third, certain semantic constraints that verbs and their arguments must meet, in terms of telicity and theme incrementality, to successfully compose with the verbal particle or, mutatis mutandis, its counterparts in English, etc., have been insufficiently studied, and explicit semantic definitions from which those constraints could be derived are largely missing from the existing literature.

We have tried to fill these three gaps by following principally one strategy: focusing on languages like Mainland Scandinavian or German, where the means to express the concept of finishing are relatively transparent, so as to gain a clear view of their distribution and their truth conditional contribution. This is a shift in emphasis away from the compositional issue of coercion or underspecification, to the issue of what the meaning is.

There are a variety of means to express the concept of finishing in Mainland Scandinavian and German, centered around a stem færdig/färdig/ferdig/fertig, which can be a verbal particle, an adjective with a theme subject, or an adjective with an agent subject and a PP where the complement can be verbal (infinitival). Because the constraint that the verb not be anti-incremental with respect to its theme argument, in a sense made precise in section 4.1, is shared by fertig etc. as a verbal particle and finish etc. as a transitive verb but not by fertig etc. as an adjective with an agent subject or finish etc. as a verbal complement verb, it is the verbal particle that corresponds most closely to the use of finish, etc. that has been at the center of attention in the literature on aspectual verbs, and this use of fertig etc. is what we have focused our main attention on.

German and Scandinavian are thus true to their type as strongly ‘satellite-framed’ languages, in the sense of Talmy (2000), as far as expressing finishing is concerned, the verbal particle being a ‘satellite’; English, on the other hand, falls into line with the ‘verb-framed’ Romance languages regarding finish.

There are basically two ways to model constraints like the one about telicity and the one about theme incrementality: one can state them, by stipulation, as a definedness condition for the meaning of the word carrying the constraint, or one can seek to make it fall out as a corollary of the definition of that meaning. We have chosen this latter way, by defining the meaning of the verbal particle in terms of an argument verb |$P$| and its argument |$x$| as yielding a set of events |$e$| such that (i) |$e$| is a final, but not necessarily a proper final part of a |$P(x)$| event, (ii) |$e$| is a |$P(y)$| event for a part, but again not necessarily a proper part, of |$x$||$y$|. In consequence, fertig is non-redundant just in case |$P(x)$| is not anti-telic and |$P$| is not anti-incremental with respect to |$x$|.

Whether redundancy in these terms constitutes sufficient reason for anomaly is a question which is open to debate, and as an alternative, we have considered the option of providing the verbal particle with the presupposition that |$P(x)$| is not anti-telic and |$P$| is not anti-incremental wrt. |$\!x$|. – As a compromise solution, finally, building on our primary proposal, we have suggested supplementing it with a more general presupposition saying that the VP with the verbal particle means something different from the VP without it.

A question which arises naturally from our analysis of the verbal particles in German and Mainland Scandinavian is whether it could also be put to use for the transitive verbs in English, French, etc. While we will not here advance a positive answer to this question, a few remarks may be enlightening.

(13) He finished the shirt and unplugged the iron.

(25) Han strauk ferdig skjorta og drog ut strykejernet.

he ironed ferdig shirt-def and pulled out iron-def

A prime argument in favor of this ‘covert verb hypothesis’ would come from the properties that are shared by the verbal particle and the transitive verb: the overt or covert verb can be any as long as it is not anti-telic or anti-incremental with respect to its theme. As we saw in section 2.4, the incrementality criterion sets non-eventive DP argument finish apart from VP or eventive DP argument finish. This could provide a special reason to model the analysis of the former on the analysis of ferdig, using (79) for this case while using the simpler (80), which does not specify anything relevant for incrementality, for the latter.

(79) |$\lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,\lambda e \ \exists \, e^{\prime } \ P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) \ \wedge \ $|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e) \, \wedge \, \exists x^{\prime } \ x^{\prime } \!\sqsubseteq x \, \wedge \, P_w(x^{\prime })(e)$|

(80) |$\lambda P_{s(e(vt))} \lambda x \,\lambda e \ \exists \, e^{\prime } \ P_w(x)(e^{\prime }) \ \wedge \ $|fin|$(e^{\prime })(e)$|

The price to pay for a covert verb analysis would be that finish, finir, etc., would be ambiguous, since beside the verb that takes a VP or an eventive DP, another would take a non-eventive DP after applying to a covert verb. This is a high price, for dual or multiple lexical entries are ideally to be avoided. Note, however, that if the verb as occurring in (13) were indeed to be modeled on the verbal particle as it occurs in (25), that would also offer an explanation for its freedom to combine with object-denoting DPs: the prediction would be that it can combine with any DP that any verb can combine with if only (i) that verb (or rather its translation) is one the particle can felicitously operate on and (ii) the content of that verb is a value supplied by the context.

While the benefits that may come from viewing German and Scandinavian as model languages regarding the notion of finishing may be counterbalanced by other concerns, it is our hope that our focus on the ways this notion manifests itself in these languages may inform the debate about aspectual verbs generally.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to fellow linguists in the SynSem group at the University of Oslo and in the CASTLFish group at the Arctic University of Norway, as well as to three anonymous reviewers for Journal of Semantics and Associate Editor Cleo Condoravdi, for very helpful comments and suggestions along the way.

Footnotes

Unless otherwise indicated, all examples are authentic or modulations of attested cases. URL source references are omitted for parsimony.

Broadly, the agentive role results in a production interpretation and the telic role results in a consumption interpretation.

Sentences like (17) are deemed ungrammatical by Pustejovsky (1995, 206) on the grounds that the sun is not an external argument and finish is a control verb, a common assumption since Ross (1972). We believe that what is at stake is not control but telicity, as there is a contrast between a telic and an atelic complement with a non-agentive subject:

(i)

I wanted to be behind the gates before the sun finished setting.

? I wanted to be behind the gates before the sun finished shining.

It may be easier to read a quantization into a bare plural than a mass nominal, e.g.:

(i) As I finished letters to friends I found myself less lonely, missing them less.

A concise definition of an appropriately weak notion will be given in section 4.

To a certain extent, these two verbs, in particular abschließen and its MSc cognates, can be used in the sense that finish is used in in (i), a non-agentive, stative sense where the object denotes a sum corresponding to a linearly ordered set and the subject denotes its ‘last’ part:

(i) A fun, asymmetrical hem finishes the dress.

(ii) …den lille krave afslutter kjolen på en eksklusiv måde. (Danish)…the small collar finishes dress-def on an exclusive manner

The situation is complicated by the fact that only the verb in a particle verb unit, if finite, moves to C in a root clause, leaving the particle behind. A further complication concerns the fact that even in MSc, particularly in Danish, the verbal particle is sometimes prefixed:

(i) Det tog mig sammenlagt ca 12 timer at færdigmale figuren.it took me together ca 12 hours to færdig-paint figure-def‘It took me in total around 12 hours to finish the figurine.'

In addition, German and MSc have an adjective ferdig etc. with the same meaning, and a similar syntax, as the English adjective ready. While it is understandable how this variant has evolved, it seems clear that it is a separate item, and we will not address it further.

One problem raised by relaxing the incrementality criterion along these lines is that the path incrementality associated with predicates of directed motion must be excluded.

German fertig will display the inverted structure, in the VP as well as in the upper V.

As a matter of fact, this definition is too simple in two respects: first, divisive reference should be relativized to dimensions; second, divisive reference only reaches down to a certain level of granularity (the ‘minimal parts’ problem) as far as activities are concerned. See, e.g., Champollion (2015) on both accounts.

Like (56), (58) oversimplifies in two ways: first, a relativization to the temporal dimension should again be built in; second, |$x$| should be relativized to its description, since whether |$P$| is anti-incremental wrt. |$\!x$| may depend on whether |$x$| is an atom relative to this description.

Strictly, anti-incrementality does not apply to this case since the bare plural object does not denote an individual or the value of an existentially bound variable; the main point is that the transitive verb is (not anti-)incremental with respect to a non-atomic individual argument.

In fact, there is a sense in which this verb is not, after all, anti-incremental with respect to this theme argument; if the patient is not moved from, say, one ward to another but from, say, a stretcher onto a table, one limb at a time, as it were, ferdig is felicitous.

See, e.g., Deo (t.a.): “Atelic predicates …typically have divisive reference”.

Still, the analysis may well need to be strengthened to avoid certain unintuitive results. In particular, a sentence with a plural theme argument like (i) is predicted to be true if, say, you ironed your shirt and I mine and we did so simultaneously.

(i) Jeg strauk ferdig skjortene.I ironed ferdig shirts-def‘I finished the shirts.’

The question remains what, if anything, is communicated with the particle in such a case. There seems to be a pragmatic effect from a focus on the finality of the (improper) sub-event; insofar, ferdig has commonalities with ‘maximizing modifiers’ (see Morzycki 2002) like whole. See also (Engelberg, 2002, 393ff.), who suggests that when a German verb with the particle auf ‘up’ is used to express the same type of event as the verb stem, the particle adds emphasis.

Svenonius (1996) notes and discusses interactions between old/new information and the relative placement of verbal particle and object generally.

References