Abstract

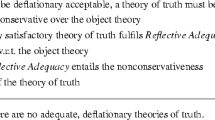

Although a number of truth theorists have claimed that a deflationary theory of ‘is true’ needs nothing more than the uniform implication of instances of the theorem ‘the proposition that p is true if and only if p’, reflection shows that this is inadequate. If deflationists can’t support the instances when replacing the biconditional with ‘because’, then their view is in peril. Deflationists sometimes acknowledge this by addressing, occasionally attempting to deflate, ‘because’ and ‘in virtue of’ formulas and their close relatives. I examine what I take to be the most promising deflationist moves in this direction and argue that they fail.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 A

Theories of truth—under which I include only those that purport to explain either the concept or property truth, the predicate (in any tongue) ‘is true’, or the operator ‘it is true that’—are not exceptional in bringing out differences that divide diehard extensionalists from concessive intensionalists, or the mind-sets of formalists from supporters of realistically interpreted theses. But such theories supply a useful test for seeing how far these quite general, and often amorphous, attitudes might take us. Simplicity versus fruitfulness, neutrality versus metaphysical commitment each have had a role to play in this drama, making truth theories an excellent laboratory for controlled experiments. On the former side of all of these divides we may find deflationary truth theories. On the latter we find inflationary ones. (As with deflationists generally, my representative inflationism is a tolerant, and latitudinarian, version of the correspondence theory of truth, hereafter ‘Correspondence’. It is outlined further below.) In this essay I propose to examine the deflationary-inflationary difference with respect to one rather narrow question: Must any acceptable theory of truth include among its tenets that a truthbearer is true because, or in virtue of something? Put otherwise, does any theory that fails to mention, perhaps even acknowledge, what it is that makes a bearer true miss something, and is it, at a minimum, inadequate to that extent? Although no simple answer suffices to mark the differences between the two sides, I believe the question itself opens up issues that sharply focus the polemical divide between deflationists and inflationists. On balance, I side with the inflationists. But the first order of business must be to get a better handle on the respective views and the options for answering our questions.

2 A

Deflationary theories of truth are a polymorphous lot, but deflationists generally agree that a complete theory of truth’s concept, property, or the predicate ‘is true’ can be achieved sans metaphysical commitments. By this I mean that we can have a wholly satisfactory account, say, of the concept truth without inquiring into the worldly conditions, or any others that make a truth-bearer true. Some of these theories may include truth-makers, or at least what they call such, but these too are invariably deflated. Radical versions may exclude truth-makers altogether. I intend to include under deflationism varieties of truth theory that are known under titles such as ‘disquotationalism’, ‘redundancy’ (or ‘superfluity’), ‘minimalism’, and ‘prosententialism’.Footnote 1 Although they diverge on details, at the heart of all of them is one of two schemata:

-

(T) ‘S’ is true (in language L) if and only if p

-

(R) <p> is true if and only if p.Footnote 2

For (T) the bearer of truth is a description or quotation name of an object-language version of that sentence; and in the central case ‘p’ exhibits that sentence, or its translation, in the metalanguage in which (T) is formulated. The primary bearers of truth on (T) are sentences, on some versions with indices for a speaker, location, and time of utterance. For convenience I follow the custom of omitting reference to a particular language. (R) takes propositions (broadly understood) as a primary truth-bearer. Unlike (T), (R) locates ‘is true’ in the language of the truth-bearer. Because this is susceptible to familiar paradoxes, recent defenders of this form who are sensitive to that threat use (R) only as a rule for generating an unlimited number of instances in which ‘p’ is replaced by the same sentence in both occurrences. Thus, to take a standard example,

-

(R1) <snow is white> is true if and only if snow is white

and any other non-pathological cases we can think of will be acceptable instances of (R). The deflationist claim is that accepting an indefinitely large series of instances of (R) is necessary and sufficient for having a concept of truth.Footnote 3 And, similarly, for (T) we will have instances such as

-

(T1) ‘Snow is white’ is true if and only if snow is white,

where ‘Snow is white’ to the left of the biconditional is offered as a quotation name of a sentence.

For even the most concessive deflationary theories the whole explanation of truth takes off from (R) or (T). For example, Horwich (1998a) writes: “Our understanding of ‘is true’—our knowledge of its meaning—consists in the fact that the explanatorily basic regularity in our use of it is the inclination to accept instantiations of the schema (R) by declarative sentences” (p. 35), and “the truth schemata are the explanatory basis of our over-all use of the truth predicate” (p. 126). Also, Soames (1999, p. 231) observes that “the leading idea behind deflationism about truth” is that the equivalence between ‘S’ is true and p “is in some sense definitional of the notion of truth”. Additions (other than the few complements noted below) would violate the prohibition against inflationism.

We should also mention a further wrinkle. Whereas (T) and (R) are the basic elements of the deflationary explanation of truth, they work only for cases in which the truth-bearer is formulated in the construction. For cases in which it is merely alluded to (e.g., ‘Whatever Il Magnifico says is true’) or generalized (e.g., any proposition of the form ‘p or not-p’ is true) a further explanation is needed. But the supplement is always equally non-metaphysical. For example, it may refer to the role of truth in allowing us to semantically ascend (say, from talk about the world to talk about sentences), as a predicate for bearers described but not expressed, for stating certain generalizations, or for inferences from one side of (T) or (R) to the other. Indeed, since it is widely believed that truth is shown to be eliminable by (R), (T), and their instances, some deflationists highlight the nonredundant cases as displaying the chief utility of our truth predicate, and thus of our concept (or the predicate’s correlative property). But these additions play a minor role in understanding truth. However, because they are equally deflationary and merely ancillary to the heart of the explanation, for simplicity I shall not bother about them henceforth.

Additional details won’t affect the use to which I shall be putting this brief deflationist snapshot. On some, but not all varieties deflationists will take their theories as directly about the predicate ‘is true’ rather than the concept truth. But for the accounts to have their intended force, they must regard the difference between that predicate and its concept as negligible (perhaps because that is all a concept comes to, or perhaps because there is no other way to examine a concept). Also, holders of (R) may prefer a propositional operator to a predicate: to wit,

-

(RO) It is true that p if and only if p.

Though I concentrate below on the predicate, the discussion can be reworded to cover (RO). One further stipulation is required if a view is to be considered genuinely deflationary. The sentence replacing the variable on the right-hand side of each biconditional at the very least must be taken as representationally neutral. If we take it to represent its subject-matter, we will have reintroduced just the worldly affiliate deflationists intend their theories to avoid.

Before engaging in polemics, some ground–rules are in order. First, as a less rebarbative title for generic truth-bearers let’s use ‘proposition’, construing it broadly. While it can stand for the meaning of an utterance or belief, I intend to use it comprehensively to cover just about any bearer a theorist prefers. Second, in spite of the essay’s title, my claim is not that the truth-conditions themselves are intensional. Indeed, I believe it is clear that any such conditions must be extensional, though in some few instances they may include intensional factors (e.g., some truths about the mental or linguistic). Rather it is the specifications of them in larger contexts introduced in Sect. 3 that are intensional. Next I noted earlier that typically the metaphysically loaded view against which deflationists contrast themselves is Correspondence, which, for our purposes, can embrace any view maintaining that a proposition’s truth consists in its relation to a state of the largely non-semantic world. The relevant version here may be variously qualified. For one thing, it could allow some secondary, derivative non-correspondence, truths; for another, some propositions may require the entire world (e.g., negative existentials, counterfactual supporting universal generalizations) for truth-maker. In addition, ‘the world’ includes merely possible worlds. Below the contrast to deflationism will be with this ecumenical version of Correspondence.Footnote 4 Finally, unless discussing a particular theorist who employs (T), I usually use (R) as my stalking-horse. The chief points can be easily extended to (T).

3 A

If the right-hand sides of (T) and (R) are to provide truth-conditions, a first thought is that these propositions are true because, or in virtue of what is signified on the right-hand side. Thus, they should be able to support

Deflationists have reacted to such substitutions in various ways. Some have tried to show that these idioms can be incorporated, with no, or only minor, changes in our current truth conception, into a deflationary theory. Others have tried to show that they can be given natural deflationary readings. And yet others have dismissed as bogus any attempt to introduce them into the discussion. The first approach is discussed in this section and Sect. 4, the second in Sects. 5 and 6, and the last in Sect. 7. But, first, taking because Footnote 5 as our focal notion, let’s note a few non-negotiable features of it, and of in virtue of, that motivate naysayers and the merely perplexed to pose this last series of challenges for deflationism.

Consider propositions of the form ‘p because q’, ‘p because of q’, and ‘p in virtue of q’ in which ‘p’ represents something factlike in form and ‘q’ may represent a (potential) fact, event, state, or process. Certain subtle differences between the first and latter two constructions (viz., in the ranges of substitutends for ‘q’) are discussed later. They turn out to be minor for our purposes. More importantly here, each is usable for stating the same range of dependencies, they affirm that p is dependent in some way on q. A first kind of dependency that comes to mind is causal, and indeed propositions of these forms are canonical for singular causal statements and beliefs. However, ‘because’ extends well beyond that. Consider

-

A natural number is prime because it has no divisors other than 1 and itself.

-

Goldbach’s conjecture is true because every even number greater than two is the sum of two primes.

-

Three aces won because no one else had as high a hand.

-

Whales are mammals because they have mammary glands.

-

The table is made of atoms because everything in the universe is.

-

It was the only thing he could do because of his peculiar circumstances.

-

She deserves the award because of her tireless efforts on behalf of the less fortunate.

And a host of further cases make the same point. The most we are entitled to claim is that our propositions state various kinds of dependency.

Because has interesting logical features. One argument against regarding it as a relation is that it is flanked by sentence-like clauses rather than singular terms. This, it has been noted, means that its terms aren’t in quantificational position. Despite that, ‘because of’ and ‘in virtue of’ can take singular, referring expressions, such as ‘his peculiar circumstances’ or ‘her tireless efforts’ on their right-hand (/antecedent) sides.Footnote 6 At any rate, the objection to because being a relation is less than decisive. Features closely mirroring those of some relations cannot be ignored. For example, it has a kind of irreflexivity: ‘p because p’ is permissible only as a clumsy, ironic, way of saying that p doesn’t depend on anything. The Oxford English Dictionary gives ‘for the reason that’ as a rough synonym for ‘because’, and however broadly we interpret ‘reason’ here, something can’t be a reason for itself (not even God). Because also behaves like an asymmetrical relation. It seems to indicate unidirectional dependence.Footnote 7

Of course, due to its regular placement between sentences, it is also common to view ‘because’ as a dyadic sentential connective. For many of our purposes, this will serve as well. As the counterpart to its concept’s ‘sort of’ asymmetry, and unlike ‘if and only if’, it is not commutative. Also, ‘because’ and ‘in virtue of’ are not truth-functional. On those grounds, they are non-extensional idioms. Thus, for ‘p because q’, the replacement of either ‘p’ or ‘q’ by another propositional clause with the same truth-value does not guarantee the preservation of truth for the whole statement.

To see the role that these features may play in our deliberations consider Wright’s (1992) claim that deflationism can incorporate, without modification, because idioms such as (BT1)—‘Snow is white’ is true because snow is white. (Although Wright is not himself a deflationist in the end, qua deflationism this would belong to the first group mentioned earlier in this section.) Starting from

-

(T1) ‘Snow is white’ is true if and only if snow is white

Wright states that once certain trivially true intermediate premisses are secured “there is no difficulty…in saving (BT1) for minimalism (or deflationism) as well” (p. 27). I criticize this derivation elsewhere (Vision 2004, pp. 113–23). Because much of that discussion doesn’t bear on the current topic, I won’t rehearse either the derivation or my full slate of objections. But there is a quite general reason why any such argument from (T1) to (BT1) must fail, connected directly with the features of because we have reviewed. Moreover, it is symptomatic of a basic difficulty in a wide spectrum of deflationary theories of truth.

If ‘p if and only if q’ implied ‘p because q’, it would also imply ‘q because p’: ‘p if and only if q’ implies ‘q if and only if p’ (commutativity), which then, by the same reasoning and with no more than the very same uncontroversial intermediate premisses, would immediately imply ‘q because p’. This would violate even the nonsymmetry, much less the asymmetry, of because.

We could also view this as a violation of irreflexivity. While the formula

-

‘Snow is white’ is true if and only if ‘snow is white’ is true

is a bit turgid, it nonetheless follows from a theorem of propositional logic. On the other hand, the falsity (perhaps even the senselessness) of

-

‘Snow is white’ is true because ‘snow is white’ is true

is clear and a priori.

Thus, without further argument we know that the implication must fail. Material, even indicative, biconditionality, ‘if and only if’, supplies covariation at most. ‘Because’ (and ‘in virtue of’) are among our clearest idioms of dependency. One cannot distill dependence from covariation.

4 A

We are now in a position to examine other efforts to incorporate because undiluted into a deflationary truth theory. But first let’s ask, ‘What good reason is there for even a deflationist to take seriously undeflated formulas from the (B) and (V) series in Sect. 3?’

For starters, the sort of covariation expressed in (R) and (T) is not explanatory of truth per se. Even were we assured that the truth-values of the sides vary in tandem (and this will be so only as long as no propositions have indeterminate truth-values), this could be due to their mutual dependence on a third thing. Not only does that fact render incomplete any theory which relies solely on this sort of biconditional, but it makes room for the possibility that what is left out is precisely that which these theorists wanted to avoid: in our case, dependence on a nonlinguistic reality accounting for the truth of both clauses. Whenever we have ‘p if and only if q’, there is always the possibility that this may be so only because our acceptance of both p and q depends, say, on r. Of course, once r is secured, we can affirm that p and q covary in truth. However, that explanation of their copresence isn’t consonant with deflationism. (R) is enlisted to provide a total account of the cases it covers, and the third term might be what the correspondentist claims it is: viz., a state of the world. The upshot of these reflections is that in the expression ‘truth-condition’ the contributing component ‘condition’ is taken seriously, and this may pressure at least some deflationists to try to accommodate the sort of dependence that is carried by expressions such as ‘because’ and ‘in virtue of’.

The problem may be illustrated by comparing (R) and (T) with

-

(O) <p> is true if and only if any omniscient, infallible being knows that p.

Of course, (O) is disqualified several times over as a definition of truth. It uses more than one overloaded, dubious, notion. [Contrary to certain claims, it does not imply the existence of an omniscient and/or infallible being. However, that requires reading the right-hand side subjunctively—‘knows that p’ to be understood as ‘were to know that p’—which makes plain a central reason for a deflationist, or any extensionalist, to ignore (O).] However, even if we overlooked those procedural flaws (O) would still be patently unsatisfactory. Bizarre theological doctrines aside, no one is likely to take it seriously as a general specification of a condition for a proposition’s truth. Some may be quick to reject (O) for its technical shortcomings, but this last feature is the more striking difference between (O) and (R). Its right-hand content is almost always unconnected with its left-hand clause. Why should it matter to the truth of the proposition that the train has arrived what an arbitrarily selected being, much less this hypothetical one, knows?

Before proceeding another clarification is in order. If (B) and (V) series pose a challenge for deflationism, their impact is primarily on non-compound propositions or on certain non-truth-functional compounds. Truth-functions such as ‘<p or q is true>’ can have ‘p is true’ as a condition for their truth. Deflationists might say we may also give ‘p’ as a condition for their truth, but that depends on how ‘p’ is regarded, and opens up just the sort of issue under investigation. If we were to claim that ‘the proposition that p or q is true because p’, that prompts the question ‘Because <p> or because <p is true>?’, which throws us back to our starting point. Nevertheless, if the truth of p accounts for the truth of p or q, that still leaves us at the level of propositional determinations of truth-conditions for our target proposition. Thus, for these, some non-truth-functional compounds (e.g., subjunctive conditionals), and propositions whose subject-matter is itself propositional, we may not need to look beyond the realm of the semantically evaluable in order to discover a truth-condition. Even traditional correspondentist theorists such as Russell and Wittgenstein were aware of that. If because, &c. creates any concern for deflationism, the central case will be the great mass of truth apt simple propositions. I shall assume throughout the rest of this essay that it is those on which we are concentrating. To avoid needless complications we may remain neutral on the ‘worldliness’ of truth-conditions for compounds whose truth is sensitive to that of one or more of their components.

Horwich can serve as a clear representative of a maximally concessive deflationist (/minimalist) who wants to account for because within a deflationary scheme. Recall that such deflationists acknowledge the relevance of the (B) and (V) series. Indeed, Horwich goes so far as to state that

…[minimalism] does not deny that truths do correspond—in some sense—to the facts; it acknowledges that statements owe their truth [my emphasis] to the nature of reality… (1998a, p. 104).

It is not obvious how to reconcile this with minimalism. However, if the notion of owing one’s truth to something can be incorporated alongside minimalism, we would certainly be able to see how (BR) and (VR) fit. But what indeed remains of an advertised non-metaphysical alternative that concedes this much to Correspondence? I haven’t a clue about how Horwich believes he can pull it off, so let me offer a few speculations. (They are failed solutions, but they may be useful for explanatory purposes.)

First, one might also have a deflated view of notions such as fact, correspond, reality, because, in virtue of, and the like, so that they now carry no more a commitment to word-world relations than the phrase ‘the proposition that p is true’ in (R). This interpretation would place the view in the next class of deflationists, who incorporate because as a deflated companion to truth. While Horwich may drop hints of this elsewhere,Footnote 8 he shows little inclination to carry out that ambitious program for philosophical theses in general. However, were he so inclined, we shall see below that his failed attempt to neutralize because exposes the weakness of the tactic.

A second possibility is that deflationism is conceived merely as an account of the predicate ‘is true’, and not of its property or concept. Horwich (1998a, p. 37) explicitly denies this: “the minimal theory of truth will provide the basis for accounts of the meaning and function of the truth predicate, of our understanding it, of our grasp upon the concept of truth, and of the character of truth itself”. Of course, for Horwich this is achieved only by first grasping the meaning of the predicate ‘is true’, and that approach is, at the very least, controversial. After all, the greater share of true propositions, for which we must account, don’t even contain a truth predicate or operator (cf. Vision 2004). Still, Horwich is explicit in the quoted passage that his minimalism is intended to cover accounts of truth’s meaning, function, concept, and property. And it is difficult to see what room this leaves for the concession quoted earlier. Of course, he is quite right to insist on this coverage. It would be utterly implausible to hold that the satisfaction conditions for the property of truth were left out of what represents itself as a full account of truth.

It remains for us to ask how Horwich’s ‘demonstration’ of this consistency proceeds. In both the 1990 and 1998 editions of Truth he regards it as a question of the order of explanation. (Although his minimalism is phrased in terms of (R), I follow him in using disquotational examples to illustrate his claims.) Suppose we want to account for

-

(BT1) ‘Snow is white’ is true because snow is white.

The first step is to gloss this as

-

(ET) ‘Snow is white’s being true is explained by snow’s being white (1990, p. 111, 1998a, pp. 104–105).

Paraphrasing ‘because’ with ‘is explained by’ diminishes somewhat the extra-linguistic impact of the former. For the moment grant the paraphrase (subject to later re-evaluation). Horwich (1990, p. 110) now reasons that together with “basic laws and initial conditions of the universe” we infer ‘Snow is white’, and then replacing the left-hand side for the right-hand side in (T1) we deduce ‘“Snow is white” is true’. Clearly, it is crucial to this reconstruction of the reasoning that (T1) show up as an intermediate premise, and this is easily generalizable to all instances of (T), although the content of intermediate laws will vary with the example.

The reasoning is not immediately clear. What grounds do the physical sciences supply for requiring the intermediate step ‘Snow is white?’ Why not go directly from the basic laws and initial conditions to ‘“Snow is white” is true?’ One would be hard put to show that the right-hand side of (T1) is more fundamental for physics and chemistry than the left-hand side, whatever might be the situation for semantics or conceptual analysis. A detour through (T1) has no place in a physical explanation. Although circuitous routes are possible for any inference, allowing them opens the door to a galaxy of bizarre desiderata.

Assuming the “basic laws and initial conditions of the universe”, an equally immediate inference would be to the left-hand side of (BT1); that is, to “‘Snow is white’ is true”. This would also make the latter an intermediate premiss from which we may then derive ‘Snow is white’ with the help of (T1). Of course, if we’re counting words, or the number of concepts involved, ‘Snow is white’ might seem the more natural choice. But how does that concern the physical sciences which are presumed to exclusively license the derivation? Horwich had to assume the priority of the right-hand side of (T) from the outset. But the only opportunity in this setting that I can foresee for a priority claim would be just the minimalist thesis to be accounted for.

I now want to challenge the earlier assumption that we can replace ‘because’ in (BT1) with ‘is explained by’ in ET. That is a mistake, a variant of the same mistake made in the 1990 edition of Truth, in an expanded version of this argument, when Horwich wrote, “in other words” (my emphases)

-

(M) ‘Snow is white’ is made true by the fact that snow is white.

‘Being explained by’ is not equivalent to either ‘because’ or ‘is made true by’. Explanation as used here has epistemic implications. Even if one or another description of an event explains something, not every description of that event does so. Thus, while the description ‘a meteorite’ may explain the explosion in Siberia, it doesn’t follow that the description ‘the event reported in the headline of yesterday’s Daily Bugle’ explains the explosion. Explanatory descriptions are subject to all manner of restrictions relating to palpability, informativeness, and relative simplicity of expression. This renders the idiom ‘…is explained by…’ non-extensional in a special way.

While constructions governed by ‘because’ and ‘is made true by’ are also intensional, because they aren’t truth-functional, the phrases can and do still express metaphysically loaded notions.Footnote 9 Unlike ‘is explained by’ they survive replacement by different descriptions of their terms. Although that applies to both terms, the point emerges perhaps more clearly for Horwich’s original ‘is made true by’. What makes it intensional is that it does not permit the willy-nilly replacement of one of its (propositional) terms by another propositional phrase having nothing more in common with it than a similarity of truth-value. (There is an added complication for ‘in virtue of’ and some occurrences of ‘is made true by’ because their right-hand substituends aren’t expressed by propositional, truth-evaluable, expressions.) Thus, if a certain proposition was made true by the meteorite landing, and the meteorite landing was the event reported in the headline in The Bugle, then the proposition was made true by the event reported on in the headline of The Bugle (though the proposition’s truth is not explained by anything under that description). The concept of being made true by does not attempt to explain as such, but simply picks out a dependency relation, regardless of its ability to illuminate this for an audience. The truth of ‘Charles I was executed’ may be made so by Charles I being executed, but that proposition’s truth is not explained by Charles I being executed. Similarly, that ‘Charles I was executed’ is true because Charles I was executed, although it would be taken under normal circumstances to be trivial. Perhaps we customarily use the idiom of ‘because’ when we want to explain something to someone. But what is normal isn’t thereby necessary.

This difference may also be made plain by looking again at the right-hand sides of (BT1) and (ET). On the right hand side of (BT1) ‘snow is white’ is a factive clause, expressing a complete thought as it stands. But on the right-hand side of (ET) we have ‘snow’s being white’, the sort of nominal suitable for designating a state, but non-sentential in form. What occurs on the right-hand side of (ET) on its surface doesn’t represent something semantically evaluable, say, a sentence or proposition. Rather, it expresses (in a broad and non-technical sense) a state of affairs. For only something that was not itself semantically evaluable could serve in general to determine the truth of a sentence of that type.

Horwich, perhaps dimly aware of just this sort of complication with (ET), chooses to formulate his ‘is explained by’ candidate with a factive clause, as follows:

-

(ET*) The fact that ‘snow is white’ is true is explained by the fact that snow is white. (1990, p. 111)

We may set aside the first occurrence of ‘the fact that’: whatever explanatory power (ET*) has wouldn’t be lost by replacing it with

-

The truth of ‘snow is white’ is explained by the fact that snow is white.

However, the second occurrence of ‘the fact that’ is revealing; on their face, facts, like states of affairs, are not suitable subjects for semantic evaluation. Although it has been maintained that facts are no more than shadows cast by true statements,Footnote 10 the onus is on that view’s adherents to overcome appearances to the contrary. The common assumption, built into our forms of speech, is that a fact is not a sentence, belief content, or proposition.Footnote 11 For our purposes it doesn’t matter whether this common assumption is correct, but only that it is common. That would help explain why it is that we must introduce the ‘the fact that’ idiom to formulate (ET) in this way. It is not merely that

-

The fact that ‘snow is white’ is true is explained by (that) snow is white

doesn’t pass muster as H.M. English; it doesn’t make any sense in lieu of a gloss.

Of course, no such alteration is called for regarding ‘because’ in (BT), ‘Snow is white’ is true because snow is white. I take it that the presence of ‘because’ rules out the right-hand side representing a semantically evaluable counterpart to the explicandum sentence. Thus, it is indifferent at this precritical level whether we say that ‘snow is white’ is true because snow is white or in virtue of snow’s being white. But just as we do not countenance

-

Snow is white because snow is white

neither do we countenance

-

‘Snow is white’ is true because ‘snow is white’ is true.

Deflationists have dealt rather peremptorily with the nuances of adjustment to our idiom separating because from biconditionality. But these facts yield clues as to why, for many, deflationist attempts to incorporate because in their theories have seemed so perfunctory and inadequate to the task at hand.

5 A

Related to the deflationary difficulty of integrating because formulas is that of supplying truth-makers. Like speakers in general, deflationists typically affirm that some propositions are true, others false, perhaps some neither. Most find it reasonable to believe that the difference consists in something, and implausible to accept that it consists in nothing. Anscombe (1982, p. 8) has labelled what amounts to elucidating the distinction between a truth and its truth-maker a “deep metaphysical prejudice”, but her charge hasn’t found much resonance, and, in any event, the best argument she seems to have against the “prejudice” is to consider only truth-functional compounds, a procedure, and example, I have given reason for rejecting. There may be other reasons for doubting that the quest for the ‘something’ behind the difference can succeed. For example, so-called pluralists may hold that the differences are too diverse to encapsulate in a unified account. Others, who we may term nihilists, may regard the issue as too deep for a formulable philosophical account, or, perhaps for that very reason, attempts to get at the difference will end up in a circle by invoking, possibly in thin disguise, truth itself. Neither of these views could be called deflationary; the deflationist is committed to offering a complete, satisfactory account of truth. Any hint that there are genuine issues for a proper philosophical theory of truth left out of them counts against deflationism. And specifying what the difference consists in, even if it is a wildly disjunctive catalogue of items, is specifying truth-makers. Without success in this endeavor, it is difficult to see how deflationism can be an adequate theory or replace a metaphysically committed view.

Since ‘because’ formulas seem to point directly to truth-makers, they are a central theme for this set of issues. If deflationists can domesticate idioms in that group, they wouldn’t need to undergo further inconvenient inquiries about truth-makers. But the substantive character of because has eluded the treatments thus far reviewed. Künne (2003) takes a different tack: he mounts an effort to show that ‘because’ itself has a deflated use or sense in such contexts. He begins with the typically, as he puts it, ontic notion of making. Prominent ontic uses of making include causal contexts (striking the match makes it light) and theoretical reductions (being H2O makes something water; p. 154). However, some makings convey nothing more than conceptual clarifications; they carry no ontic weight. A slightly simplified version of his illustration is

-

His being a child of a sibling of your parent makes him your first cousin.

Now the particular argument Künne employs requires that there exists a corresponding conceptual use of ‘because’. For our limited purposes we can regard ‘because’ as the converse of ‘makes’: thus, if y makes x, then x because y. A complementary formula for Künne’s example might be

-

He is your first cousin because he is a child of a sibling of your parent.

Applying this to our current subject, we obtain

-

(MR) The proposition that snow is white is made true by the fact that snow is white.

-

(BR1) The proposition that snow is white is true because snow is white.

The claim nust be that these too are mere conceptual clarifiers of the truth predicate. Indeed, Künne’s discussion running up to his claim hints that (BR1) will also be more revealing about the restricted clarificatory force of the construction for two reasons. First, an explicit appeal to facts is absent in (BR1). Second, its right-hand side is not a singular term and as such it is not in quantificational position. That is, there is no thing required to make the proposition true. The surface grammar of (MR), on the other hand, disguises this fact, but, Künne claims, it states no more than (BR1). In sum, the work of both operators is only to clarify the concept truth, not to provide something on which truth depends (as it would if it were a causal or a theoretical account).

Künne’s argument for the exclusively conceptual role of ‘is made true by’, ‘in virtue of’, and ‘because’ is discursive, but here is what I take to be its drift. It is granted that none of these idioms are captured by ‘if and only if’ and that formulas such as (MR) and (BR1) aren’t intended to express either causal connections or theoretical (viz., scientific) reductions. Presumably the only other option for their having ontic import is that they are entailed by (T) or (R). But when we review those entailments we find all sorts of untoward consequences, suggesting that these are word-word relations rather than word-world ones. The upshot: formulas such as (BR1) and (BT1) deliver no more than conceptual clarifications.

I have five critical comments to make concerning this set of objections to an ontic significance for (MR) and (BR1). (In Sect. 4 we take up the positive proposal, the entailment of one side of the truth formulas by the other.)

First, if my skeletal summary of Künne’s reasoning is fair, notice how little support it gives to his conclusion. As he is no doubt aware, we could have started from (BR1) to (MR), and argued that despite appearances truth has hidden ontic commitments that the surface grammar of ‘because’ disguises. Moreover, the interchangeability of ‘makes’ and ‘because’ idioms applies also in cases Künne is committed to regarding as ontic. For example,

-

Putting the wax too close to the fire made it melt.

-

The wax melted because it was put too close to the fire.

-

Being composed of H2O molecules makes a substance water.

-

A substance is water because it is composed of H2O molecules.

Also, the objection seems to rely on an assumption that once we have identified that an idiom clarifies a concept, there is no point in seeking its further implications, or that Künne’s taxonomy divides things into exclusive classes, or that causation and theoretical reduction exhaust all the ontic notions. I challenge each of these in later remarks.

Second, since Künne allows that ‘makes’ has metaphysically committed uses, he cannot regard ‘because’, despite its not mentioning a thing in its right-hand clause, as ontically innocent. As noted earlier, ‘because’ constructions are commonplace in reporting singular causal statements, and thus, on his taxonomy, carry ontic weight. Consider the pairs

-

Striking the match caused it to light.

-

The match lit because it was struck.

-

The heater’s breaking down caused the pipes to freeze.

-

The pipes froze because the heater broke down.

-

Drinking hemlock caused Socrates’ death.

-

Socrates died because he drank hemlock.

Despite its lack of singular terms, how could ‘because’ fail to signify a relation when its use in stating singular causal propositions is standard? And if its surface grammar is no obstacle in these cases, how can its appearance in (BR1) show otherwise?

Third, ‘because of’, ‘in virtue of’, and ‘is made true by’ take only singular terms in their truth-maker slots. Thus we have

-

(B.a) The proposition that snow is white is true because of snow’s being white.

-

(B.b) The proposition that snow is white is true because of the fact that snow is white.Footnote 12

-

(V.a) The proposition that snow is white is true in virtue of snow’s being white.

-

(V.b) The proposition that snow is white is true in virtue of the fact that snow is white.

-

(M.a) The proposition that snow is white is made true by snow’s being white.

-

(M.b) The proposition that snow is white is made true by the fact that snow is white.

Not only do their right-hand, truth-maker sides admit singular terms (either compound nouns or factive clauses) but they do not admit sentences:

-

*The proposition that snow is white is true because of snow is white.

-

*The proposition that snow is white is true in virtue of snow is white.

-

*The proposition that snow is white is made true by snow is white.

The right-hand phrases licensed by the foregoing (B), (V), (M) series are, in Vendler’s (1967) terms, imperfect nominals: they don’t completely shed traces of the verbal forms from which they in theory derive. One test is that they take adverbs, but not adjectives. Thus, we have ‘snow’s probably being white’ but not ‘snow’s probable being white’.Footnote 13 Working backwards we can recover from them the sentence (not the assertion) ‘snow is white’. Perhaps that is some indication that ‘because’, despite its surface appearance, may be closer than Künne credits to hosting a term in quantificational position. I don’t take this as decisive; but together with the current list of difficulties in construing because as no more than a conceptual clarifier, it is a tantalizing consideration.

Of course, we can find a similar restatement for Künne’s first example, e.g.,

-

He is your first cousin because of being a child of a sibling of your parent.

From this, it might be concluded that the possibility of a singular term in truth-maker position shows nothing. But that threatens Künne’s view rather than the one he discards. It is for him to show that the phrases flanking ‘because’ not being in quantificational position reveals something relevant, not for his opponents to show why that isn’t so. We can restate virtually any proposition such that its original singular term loses that syntactical position,Footnote 14 and this is irrelevant to our acceptance of its ontic commitment. Perhaps it is more to the point that the (B), (V), and (M) pairs admit only nominals.

Fourth, as mentioned earlier, there are semantic grounds for rejecting the proposition ‘snow is white because snow is white’ or any other proposition of the form ‘p because p’. Künne makes a related claim, though I don’t fully grasp his explanation. He rejects propositions of the form

-

(P) If the statement that p is true, then it is true because p

for the reason “that ‘It is true that p’ and ‘p’ are cognitively equivalent” (p. 151). However, even the deflationists treated earlier seem to agree, at least tacitly, that it is sensical to hold that

-

(BR) The proposition that p is true because p.

If (BR)’s right-hand side were regarded as doing no more than conveying another proposition, it would also be cognitively equivalent to the other side in Künne’s presumed sense. The acceptability of instances of that form appears to require that the second occurrence of p be regarded differently—as an implied ‘that’-clause, and thus a truth-maker rather than a simple repetition of the proposition whose truth is under consideration. Künne may not agree that (BR) makes sense. But the case for its being in good order seems strong. When we encounter cases which do strike us as impermissible because of the cognitive intimacy of the terms, as in ‘p because p’, my earlier explanation—viz., that because displays something like irreflexivity—is still available Künne’s explanation in terms of cognitive equivalence would then be otiose. But this provides yet another reason to suspect that ‘because’ furtively expresses a relation. Künne’s second reason for preferring the form of (BR1) over (MR) as a truth-maker is both unnecessarily controversial and plausibly avoidable.

Fifth, grant, pro tem, that a proposition clarifying a concept has no ontic implications as such. (We leave Anselm aside.) Certainly nothing about what (actually) exists is implied by the fact that a white, equinelike creature with a single horn in the middle of its head, having magical powers, and tamed by virgins is a unicorn. However, Künne has chosen the wrong target. Giving merely truth-conditions says nothing about its proposition actually being true. Strictly speaking, it doesn’t even say that there are any truths (save for its pragmatic implication that these statements of truth-conditions are themselves true). But if Künne admits that there are some truths, as we have assumed, then because cannot be so readily dispatched. For the because formulas with which we have replaced the biconditionals imply not only that such-and-such is a truth-condition, but also that the condition has been satisfied.

-

(BR1) The proposition that snow is white is true because snow is white.

Replacing ‘if and only if’ with ‘because’ tells us that the proposition is true, and tells us why. And a similar result holds for all the (B), (V), and (M) examples. This vital difference has the potential to overturn virtually all the attempts to derive (BR) from tenets acceptable to deflationism.

An interesting feature of (BR1) is that it is initially ontic on Künne’s taxonomy and it indirectly clarifies that particular proposition by virtue of the homographic specification of its truth-maker. Künne mentions no reason why something cannot both clarify a concept and be ontic; moreover that exclusionary claim encounters serious difficulties. For example, Künne gives causal relations as paradigms of ontic notions. But good causal connections sometimes supply conceptual clarifications as well. Sunburns must be caused by the sun, footprints by feet, floods by liquids, and statues by intentional agents. I am not suggesting that the relation of a truth-maker to its truth is causal (more on this in Sect. 6), but these instances are enough to show that, even if (BR1) conceptually clarifies something about truth conditions, its ontic standing is not thereby undermined.

6 A

There is a further important, occasionally even inadvertent, route to deflationism—the belief that the relation between a truth and its (putative) truth-maker is entailment. Because Künne meticulously develops the view and its consequences (roughly, on pp. l54–65), I once again highlight his contribution. But the view is so widely accepted with minimal argument that it might be regarded as the orthodoxy on truth-making.Footnote 15 (While perhaps not everyone who has contributed to the issue shares the view, I have yet to see it rejected in print.) The view in question might be summed up by saying that in (R), (BR), or their instances, the crucial truth-making phrases are paraphrasable in, and illuminated by, the following truth-maker ‘axiom’:

-

(TM) <p> is true entails that its truth-maker exists. (Or, more simply yet, ‘<p> is true entails p’.)Footnote 16

Typically the view develops from the notion fundamental to all such theories, that the truth of a proposition necessitates the existence of something that makes it true. Truth-maker theorists as well as their critics then spell out necessitation as entailment. Indeed, once we have ruled out causal and empirical theory-reduction interpretations, entailment may look like the single remaining promising way to understand the necessitation. And, quite obviously, this explanation will also cover the roles of ‘because’ and ‘in virtue of’ in truth-making contexts.

A companion view is that the right hand side of (TM) entails the truth of its proposition. Dodd supplies a popular version.

-

(TM*) If <p> is true, there must be one thing whose existence entails that <p> is true (2001–2002, p. 71n, my emphasis).Footnote 17

Elsewhere Dodd (2001–2002, p. 71) also formulates a truth-maker principle as (TM). Of course, (TM*) is (TM)’s converse. Although (TM*) is a significant part of the outlook I want to examine, and many of those of current interest formulate it in this way, it requires supplementation in a way that (TM) doesn’t. If we believe that there can be a world of what would otherwise be truth-makers without propositions, the entailment fails.Footnote 18 There should be easy ways to remedy this, such as rigidifying the truthbearer so that in any possible world it is our actual truthbearer that is entailed. Or we can say that if that proposition exists, then if it is true there must be one thing whose existence entails its truth; or, if we allow quantification over propositional variables and are allowed to quantify out of ‘< >’ contexts, we could frame this as

-

(∀p)[E! <p> → (∃q) ~⋄(q ∧ ~p)]

In any event, I plan to ignore these complications. My chief concern is with the belief that we can spell out truth-making via entailment in either (TM) or (TM*), though for illustration’s purposes I concentrate on (TM). The point to be emphasized is the view, as stated by Bigelow (1988, p. 126), that “every case of truth-making will be a case of entailment”. That relationship, I maintain, ‘reduces’ the connection between the two sides to one between propositions, and thereby frustrates the search for a worldly truth-maker. It converts the truth-maker into a semantically evaluable entity, on a linguistic or quasi-linguistic level with the truth it is supposed to create. The acceptance of this view is fatal to both (TM) and (TM*) as successful paths to discovering generic truth-makers. Let us then examine the critique of truth-maker theory that arises from Künne’s further ruminations on (TM).

Künne takes the previously noted via negativa route when vetting phrases such as ‘because’, ‘by virtue of’, and ‘is made true by’, and concludes that entailment is the only way to uncover the word-world relations between a proposition and its truth-maker. The issue comes to a head several pages later, but the fatal misstep is taken earlier. First, Künne writes that a truth-maker for p, call it ‘x’, is such that “(i) the existence or occurrence of x ensures that the statement that p is true, and (ii) x is what the statement is about or what it reports on” (p. 158). He then elucidates (i) as follows:

‘the existence or occurrence of x ensures (guarantees, necessitates) that…’is equivalent with [my emphasis] ‘That x exists or occurs entails that…’. (p. 159)

That is, we are to read ‘ensures’, ‘guarantees’, and ‘necessitates’ in this context as ‘entails’. However, anything suited to appear as either a premise or conclusion in an entailment is a semantically evaluable item—say, a proposition or sentence. Accordingly, Künne phrases this thesis to conform when he replaces the descriptive noun-phrase on the left-hand side of the equivalence, “the existence or occurrence of x” (which, being non-propositional, can’t entail anything), with the clause on the right-hand side, “that x exists or occurs”. Although, this is now (TM*) rather than (TM), more importantly the relation is spelled out in terms of entailment. So not only is the true proposition an inhabitant of the semantic realm, so too is the truth-maker. Indeed, Dodd (2001–2002, p. 71n), a contributor to this orthodoxy, is explicit about this. After stating (TM*) he notes that “…it would be wrong to interpret (TM*) as saying entity α entails a truth. The claim, rather, is that <α exists> entails<<p> is true>”.

In spite of Künne’s statement that ‘because’ formulas instantiating (BR) provide an ontological grounding rather than a conceptual clarification—at least in intent—the equation of ‘making true’ with entailment undermines that desideratum. It diverts us to inspect only failed candidates to supply the grounding, guaranteeing that no candidate will break out of the circle of the linguistic or quasi-linguistic. As a consequence, a few pags later Künne notes the following:

Suppose that a certain event X makes some empirical truth true. Then whatever that truth may be, each logical truth is entailed by it, according to the orthodox conception. Hence, [by a logical principle for ‘makes true’], X makes each logical truth true (p. 163, my emphasis). (cf. Restall 1996, p. 333)

This, he takes it, is fatal to the last hope for truth-maker theory. However, insofar as it is a difficulty, that may be placed at the doorstep of a standard account of entailment. It is not a problem for the notion of a truth-maker per se. Any proposition—including any falsehood and the proposition that ideal logicians know all logical truths—entails every logical truth. The lesson we are to draw from this has been interpreted in diverse ways. One natural moral says simply that a logical truth will remain so no matter what truth-makers there are. It is unclear why that should be taken as a problem for truth-maker theory.Footnote 19 It shows only that logical truths are indifferent to any proper subset of truth-makers. And, of course, any hint of a problem would disappear if we didn’t introduce entailment to explicate how a truth ensures, necessitates (and so on) at least one truth-maker.

Some truth-maker advocates have been inspired to appeal to non-orthodox, say relevance, logics as a way to avert this result.Footnote 20 Perhaps this is an effective expedient against the specific problem of necessary truths; but put forward as the ultimate solution it strikes me as a Mephistophelean bargain at best and it fails to address the central issue. First, to place exclusive reliance on relevance logic is to engage in a battle on a number of controversial fronts unrelated to (TM) or (TM*). That offers hostages to fate gratuitously. Without entering into details, if relevance logics had no drawbacks (e.g., in scope, in excluding some intuitively appealing theorems and implication rules), they would have achieved a much broader consensus by now. But second, and more importantly, even if that appeal eliminates the notorious paradoxes of entailment, it still requires a truth-maker specified as semantically evaluable. That should be troublesome for anyone who seeks a perfectly generic formula for truth-makers.Footnote 21

Consider the notion of semantic entailment: A semantically entails B if and only if there no possible world containing A that does not also contain B.Footnote 22 This may appear to put to rest my misgivings about entailment. It covers formal (syntactic) entailment, but it also holds for entailment between merely conceptually related truths—e.g., <Fred is a bachelor> entails <Fred is unmarried>—and, assuming externalism, it holds for relations where there isn’t even a hint of semantic intimacy between the contents of the propositions—e.g., <This sample is water> entails <This sample is H2O>. It does reintroduce the problem over necessary truths as one concerning necessary beings, and it is unclear how we are to rid ourselves of this problem in a non-ad hoc and uncontroversial way. But that isn’t the chief difficulty I find with this solution in the present context. More basically semantic entailment is cold comfort to those who would choose entailment as the best way to come to understand the truth-making relation. Rather than elucidating semantically neutral (or underdetermined) necessitation in terms of entailment, the reverse is the case—entailment is now understood in terms of necessitation. And while it is still possible to demand that A and B range exclusively over propositions, there is no compelling reason driving that restriction. It is equally reasonable to hold that A and B also range over states of affairs, facts, and other such non-semantically contentful items. So the appeal to semantic entailment makes no progress in clarifying, or formalizing, the problematic deflationary notions with which we began.

If entailment isn’t the right way to describe the relation between a truth and its truth-maker, what’s the alternative? Here I must be unabashedly brief and inadequate, and for simplicity I confine myself to empirical truths. But we aren’t far off the mark if we call the relation constitution: a truth-maker constitutes the truth of a proposition. This is much the same sense as that in which Socrates’ death constitutes Xantippe’s becoming a widow, or the way in which gamete donors constitute an offspring’s parentage, or the way in which smuggling constitutes a crime. Here we needn’t decide between facts, events, thick entities, states, situations, or whatnot as truth-makers. Rather, the leading point is that the worldly something will not be a bit of language or a semantic content,Footnote 23 save for the rare case in which the subject-matter is itself language-like.

A further qualification should protect this view from one potential source of confusion. A species of constitution, which I shall call ‘composition’ is a mereological relation. In many, perhaps most, cases when x constitutes y, x also composes y. A symphony is constituted by and composed of notes, a beach is constituted by and composed of particles of sand, an apple is constituted by and composed of atoms. However, it is not part of the present proposal that truth-makers compose truths. Socrates’ death does not compose (is not a mereological construction of) Xantippe’s widowhood. Similarly, a part of a fact needn’t be part of a truth. One reason is that, setting aside Russellian singular propositions, a proposition, considered as a vehicle of truth, will be composed of words or concepts, rather than moderate-sized dry goods. For another, I believe it is important to remain neutral on the question whether propositions are necessary entities. Thus, we should not rule out possible worlds, or even parts or epochs of the actual one, in which the naturalistic furniture for truth-makers is present, but there are no propositions. On the other hand, the parts and their structural relations are generally sufficient conditions for what they compose: if we have the notes, sand, and atoms, and their structural relationships, we have the symphony,Footnote 24 the beach, and the apple. But a truth-maker isn’t in that sense a sufficient condition for a truth unless its proposition exists. Perhaps either a Russellian theory of propositions or propositions as necessary entities is the best view. But our theory of truth-makers shouldn’t hang on either result.

Constitution has the right sort of fit. It is consistent with the fact that the relation between truths and truth-makers may be many-one (e.g., ‘Shakespeare wrote Hamlet’ and ‘Someone wrote Hamlet’ have the same truth-maker) and the fact that the relation may be one-many (e.g., ‘Someone wrote a play’ is made true by the fact that Shakespeare wrote a play and by the fact that Stoppard wrote a play). The relation is asymmetrical (entailment being at most nonsymmnetrical), and it is nontransitive (as entailment is not). If z constitutes y and y constitutes x, it doesn’t follow that z constitutes x. Consider, for example, a $10 bill constituted by a scrap of printed legal paper. The printed rectangular sheet may be constituted by a swarm of atoms, but it would be stretching things to say that the $10 bill was constituted by a swarm of atoms. Constitution, it seems, is restricted to certain connecting levels, but in a descending hierarchical structure it need not reach levels well below those. Moreover, constitution is sharply distinguished from both causation and identity, and doesn’t run into difficulties concerning irrelevant contents. Thus, it has the desirable features we wanted in a truth-maker without the various pitfalls of entailment.Footnote 25

Does this imply that truth supervenes on being? Not if potential truth-makers can obtain when the propositions that they make true don’t exist. In perhaps the largest share of typical cases, when x constitutes y, y also supervenes on x. But that is not invariably so. A certain lump of matter may constitute a statue, but it is not sufficient for that statue: to be a statue it must also not be a wholly natural construction. (Otherwise, every rock or clod of dirt would be a statue, whether or not anyone paid attention to it, or even if no intelligent beings ever existed.) Thus, the supervenience of truth on its truth-maker depends on the truth of the necessitation thesis underlying (TM*). Under the circumstances we might wonder what could be meant by the truth-maker constituting a proposition’s truth? All I intend is that if there is a true proposition (whether it consists of concepts, words, Platonic forms, or individuals plus relations), the stuff that makes it so is its truth-maker. If propositions are necessary existents, then the stuff, assuming it obtains, is always consistent with proposition’s truth. But this is not something that can be derived from a thorough examination of the stuff as such, and so we may regard it as orthogonal to an account of the truth-making relation.

That much of an account suffices to sketch what we might have in mind by a competitive alternative to (TM). A focused exploration of the topic would warrant a more thorough and precise formulation of this, perhaps mildly regimented, notion of constitution. But here I want only to point the way to an understanding of worldly truth-makers that both avoids the doomed entailment approach and leaves room for truth-makers that could make robust sense of our ‘makes true’, ‘in virtue of’, and ‘because’ truth formulas.

7 A

A last move would be simply to dismiss ‘because’, ‘in virtue of’, ‘made true by’ and the like from the discussion by refusing to acknowledge the force of (BR), (VR), and (MR). Although I have heard such dismissive remarks in discussion, I haven’t found perfectly explicit support for it in the professional literature.

Prima facie, Alex Oliver (1996) may look like a promising representative of the view. He writes that “‘in virtue of’ really ought to be banned” (p. 69n). But the context of this remark is what he takes to be a confusion between two interpretations of truth-makers; whereas (TM) demands ‘only’ truth-makers, what we have called (TM*) requires an ontological commitment to them. (The complaint may be easily extended to ‘because’.) Oliver’s distinction puzzles me. It can’t just be a question of the order in which the truth-maker and truthbearer clauses occur. And I don’t know what to make of the distinction between mere truth-making and ontological commitment? It seems truth-making involves ontological commitment unless we believe truth-makers might all be ‘constructivist’ in character. Oliver’s subsequent discussion is not much help in clarifying these matters. It is focused specifically on a critique of Armstrong’s use of truth-makers to interject universals, and deals only with the difficulty of specifying the right one. He doesn’t even suggest that the quest for a truth-maker is hopeless, but simply warns against its taking certain directions. However, our author seems wedded to (TM*), and I have already explained the havoc wrought here by entailment. If that is what we are to have in mind by ontologically uncommitted truth-making, Sect. 6 has highlighted its shortcomings.

Earlier, Oliver had broadened the critique of ‘in virtue of’ by stating that we are “in the realm of murky metaphysics by the presence of (these) weasel words” (p. 49). Here it doesn’t seem to matter where the phrases they govern pop up. In any event, it is hard to know why the founding intuition underlying (TM)—that a truth necessitates that something or other makes it so—doesn’t immerse one in an ontological commitment. Thus, whereas Oliver’s published comments strike me as close as we are to come to someone who simply refuses the gambit of accounting for (BT) and (VT) reformulations, I haven’t been able to uncover a further rationale for it. I therefore propose we take a different tack to search for a blunt dismissal of the because formulas.

Although Field (2001) doesn’t deliver verbal broadsides against (BT), he does try to see how far a deflationary theory which includes truth-conditions can go without the using any non-extensional tools. His results indicate that he thinks that the project is pretty feasible.Footnote 26 He writes:

…the cognitive equivalence of ‘“Snow is white” is true’ and ‘Snow is white’ will lead to the (more or less indefeasible) acceptance of the biconditional ‘“Snow is white” is true iff snow is white’, and a natural way to put this (more or less indefeasible) acceptance is to say ‘“Snow is white” has the truth conditions that snow is white’. A pure disquotational notion of truth gives rise to a purely disquotational way of talking about truth conditions (2001, pp. 106–117).

I omit much of Field’s detailed theory, confining my attention to his appeal to strictly deflated truth-conditions. In effect, it is a license to ostracize substantive, metaphysically loaded ‘because’ claims without further ado.

(T1)—‘Snow is white’ is true if and only if snow is white—needn’t be challenged. But, if asked “What is the condition for the truth of ‘Snow is white’?” a natural answer in the vein of this way of proceeding might be

-

(a)

snow’s being white.

That’s not revealing, perhaps it is rude. Nonetheless, it makes sense, and, more importantly, is of the form of a condition for something’s truth. But it does not disquote the sentence ‘Snow is white’, or even denominalize the proposition in (R1). On the other hand, if I did merely disquote that sentence, my answer

-

(b)

snow is white

would be puzzling at best. Not that we can’t make sense of this awkward reply, but the only sense I can attach to it is that it is a mannered or tortured way of stating what would be conveyed by (a). Sentence (b) doesn’t come up to being a deflated truth-condition because without taking it as a poor way of trying to say something else it isn’t any kind of truth-condition. Perhaps this has something to do with extensional biconditionality expressing only covariation: it doesn’t take with proper gravitas the request for a truth-condition, rather than something that is in some way equivalent to our original. In any event, the substitution of (b) exposes the fact that it doesn’t display the form of a truth-condition. I am not aware that deflationists, who promiscuously rephrase their answers as noun-clauses such as (a) and sentences such as (b), ever pause to ask whether their differences are more than a grammatical quirk. But the differences do indicate distinct ways of conceiving truth-conditions.

One reason that may have led philosophers to overlook this distinction is that in Field’s very standard phrase “has the truth conditions that snow is white” the operator ‘that’ doesn’t go with the first four words, but with the last three to form the factive nominal clause

-

(c)

that snow is white.

Thus, it heralds in something factlike, which prevents it from doing nothing more than disquoting the sentence on the left-hand side of (T1). (c)’s divergence from (b) is enough to undermine the latter’s use as a reason for supposing it is a deflationary truth condition.

Moreover, the account introduces a subtle change of subject. On disquotational or denominalization accounts in which the right-hand side is enlisted for the role of a truth-condition

-

(i)

…is the truth-condition of…

is tantamount to the relation

-

(ii)

…has the same truth-condition as….

The left-hand side of (ii) clearly allows only a sentence or a proposition, and on this deflationary account its right-hand side is debarred from locating a worldly truth-maker. We are left with semantic evaluables flanking the relational expression in (ii). To say that two sentences have the same truth-conditions is not to say what that truth-condition is. A sceptic or (more fashionably) an eliminativist could claim that there is no what beyond supplying two items having the same truth-conditions. Thus, we arrive in the same hopeless situation as the truth-maker axioms discussed in Sect. 6, though not via the imposition of entailment. Since Field is only proposing deflationary truth-conditions, he cannot be faulted on the grounds used to reject the views of those honestly pursuing inflationary ones (whether or not they despair of success). But whatever success he has results only from replacing the quest for (i) by a search for (ii). [Those familiar with this style of philosophizing may recognize in this an analogue of Quine’s move from the search for meaning to one for ‘means the same as’ (viz., synonymy).]

Field’s result isn’t impossible or even philosophically incoherent; but it has about it the whiff of false advertising. Having the same truth-condition as is not giving us an account of truth-conditions, much less a deflationary one. It may weakly suggest that such an account is in the offing (though difficulties with such inferences from ‘the same’ are notorious), but nothing in any account alluded to thereby indicates that it will be deflationary. Thus, he has yet to supply us with an account of truth-conditions. It might be claimed that we have been given everything to which we’re entitled. But, then, this maneuver has done no more than arrogate the previously understood term ‘truth-condition’ in an unfamiliar way. The result seems to me more akin to nihilism about truth than deflationism.

Returning to an earlier theme, we seem to have only three choices—either every proposition (/sentence) is true, none are true, or some are true while others are not. I assume Field would reject the first two options. But if there is then a difference, it is difficult to see how anything one is willing to call a truth-condition cannot but play a central role in accounting for it. And if it has such a role, it is difficult to see how it could be ‘deflationary’ in any of the senses of that term currently in play. But what grounds could there be for using the expression ‘truth-condition’ if the item isn’t suited for that role? (ii) brings out the difficulty of citing deflated truth-conditions for any such role. The mouthing of the formula itself couldn’t be what accounts for the difference. How does citing it differ in substance from holding that nothing tells us why sentences differ in truth-value, or that nothing is a truth-condition?

8 A

Of course, surveys such as this always run the risk of overlooking a promising newcomer. But if there are no other competitors, and the onus is on deflationists to produce it, it looks as if deflationary theories, in their efforts to remain above the fray, have supplied too paltry an assortment of tools to avoid soiling their hands with the metaphysics of truth.

Notes

The list is intended to include major varieties, but doesn’t aspire to being exhaustive. In the other direction, disquotationlism in particular is compatible with a non-deflationary view. Still, the most prominent self-professed disquotationalists are deflationists. Also, some inflationary theorists label their view ‘minimalist’.

I employ Horwich’s useful abbreviation ‘<p>’ for ‘the proposition that p’.

For our purposes we can restrict ourselves to so-called ‘homophonic’ or ‘homographic’ instances of these formulas.

It would be distracting here to argue the point, so I simply assume that Correspondence’s chief inflationist competitor, The Coherence Theory, is a less plausible view. At any rate, that largely accords with the Zeitgeist.

Although italics are used for others reasons as well (e.g., emphasis, book titles), when discussing concepts (/notions) rather than linguistic constructions, I italicize the word or phrase. The linguistic and concept idioms are ordinarily interchangeable here. (One reason for switching to the concept idiom is to remind us that we are not discussing expressions in a particular language, but notions that might be expressed in any natural language.)

Due to the central role of because in causal statements, the appearance excluding it from being a relation may be misleading. We examine this in greater detail later.

Some may want to claim that mutual dependency cannot be ruled out here: ‘p because q and q because p’. It will serve our purposes below (which are largely concerned with causal contexts) that because is at least nonsymmetrical, though I shall continue, for simplicity, writing as if it is asymmetrical.

Horwich (1998b), Meaning (Oxford University Press) where a deflationary, use theory of meaning is proposed.

Wolfgang Künne remarks that “[f]acts, being abstract (non-extensional) entities, are not part of the natural (spatio-temporal causal) order” (p. 158n201). ‘Because’ and ‘is made true by’ sentences are equally non-extensional, but clearly can be used to make metaphysical, non-linguistic, claims. If their non-extensionality is strictly the result of prohibiting replacement salva veritate of their contained propositions by any other of like truth-value, that would scarcely be a barrier to either of their terms representing something in the natural order. What follows is only that they are subject-matter specific. Moreover, as noted in the next section, there is no more direct way to make singular causal claims than with ‘because’ sentences. Clauses governed by ‘the fact that’ are also permissible in causal contexts. ‘The fact that she was careless handling the toxins caused the contamination of the laboratory’, ‘The fact that the plane hit an air pocket caused it to go into a tailspin’, ‘The fact that his hand shook nervously caused him to spill the water’.

That view is critically examined in Vision (2004).

Horwich (1998a, p. 106) appears to agree, stating of ‘snow is white’ and ‘the fact that snow is white exists’ that they “report different (though intimately related) states of affairs”.

Künne distinguishes the connective ‘because’ from the preposition ‘because of’ on p. 150. What seems more significant that the related notion of because is enlisted in both instances.

On the other hand, taking articles is a sign of a perfect nominal, and we allow talk of ‘the snow’. But it is fairly obvious in those cases that ‘snow’ is abbreviating a count noun, perhaps ‘patch of snow’ or ‘snowfall’.

See Quine (1966, pp. 230–234).

Cf. Bigelow (1988, p. 126): “Whenever something is true, there must be something whose existence entails in an appropriate way that it is true”.

Cf. Fox (1987, p. 189), “By a truth-maker for A, I mean something whose very existence entails A”; Restall (1996, p. 332), “For any A, s is a truth-maker of A if and only if s exists, and it is impossible that s exist without A. That is, s ∣= A if and only if E!s ∧ ~⋄ (E!s ∧ ~A)”; Oliver (1996, p. 69), “T is a truth-maker for the sentence S iff ‘T exists’ entails ‘S is true’”.

This is more pressing for those, such as Restall, who take sentences as their truthbearers than it would be for those who regard propositions as eternal and necessary entities.

No doubt this isn’t the only ground for misgivings about truth-makers, but it does address one sort of confusion. Issues about truth-makers for negative propositions, abstract propositions, counterfactuals, &c. may remain. But this essay is devoted solely to concerns over ‘because’ and ‘in virtue of’ formulations of truth-conditions.

It needn’t be claimed that all truths, including truth-functional compounds, require truth-makers. The problems for these glosses would arise if any truth needed a worldly truth-maker.

Assuming that we can distinguish content (/meaning/sense) from reference.

If a symphony is an artifact, it appears it also requires the intentions of at least one composer.

And, unless I have missed something, it also avoids Restall’s (1996, p. 334) dire consequence of truth-maker monism.

While he raises some unresolved issues in a postscript (also in 2001), they are inconclusive for him and they don’t address our immediate concerns.

References

Anscombe GEM (1982) Making true. In: Teichmann R (ed) Logic, cause and action: essays in honor of Elizabeth Anscombe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bigelow J (1988) The reality of numbers: a physicalist’s philosophy of mathematics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dodd J (2001–2002) Does truth supervene on being? In: Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, vol 102, pp 69–86

Field H (2001) Deflationist views of meaning and content. Originally published in Mind (1994) 103:249–285. Citations are from reprint in Field, Truth and the absence of fact (Oxford University Press)

Fox J (1987) Truth-maker. Aus J Philos 65:188–207

Horwich P (1990) Truth. Blackwell, Oxford

Horwich P (1998a) Truth, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Horwich P (1998b) Meaning. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Künne W (2003) Conceptions of truth. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Mclaughlin BP (1997) Emergence and supervenience. Intellectica 25:25–43

Oliver A (1996) The metaphysics of properties. Mind 105:1–80

Quine WV (1966) Variables explained away. In: Selected logic papers. Random House

Read S (2000) Truth-makers and the disjunction thesis. Mind 109:67–79

Restall G (1996) Truth-makers, entailment and necessity. Aus J Philos 74:331–340

Rundle B (1979) Grammar in philosophy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Smith B (1999) Truth-maker realism. Aus J Philos 77:274–291

Smith B (2002) Truth-maker realism: response to Gregory. Aus J Philos 80:231–234

Soames S (1999) Understanding Truth. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Vendler Z (1967) Facts and events. In: Linguistics in philosophy. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Vision G (2004) Veritas. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Wright C (1992) Truth and objectivity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vision, G. Intensional Specifications of Truth-Conditions: ‘Because’, ‘In Virtue of’, and ‘Made True By…’. Topoi 29, 109–123 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-009-9071-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-009-9071-6