Abstract

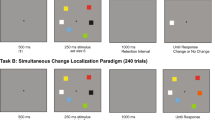

According to the influential thesis of attentional transparency (AT), in having or reflecting on an ordinary visual experience, we can attend only outwards, to qualities the experience represents, never to intrinsic qualities of the experience itself, i.e., to “mental paint.” According to the competing view, attentional semitransparency (AS), although we usually attend outwards, to qualities the experience represents, we can also (perhaps with effort) attend inwards, to mental paint. So far, philosophers have debated this topic in strictly armchair means, especially phenomenological reflection. My aim in this paper is to show how to design an experiment, using the change detection paradigm for studying visual working memory that, if yielding positive results, would support AS. The structure of the argument is as follows. In standard change detection tasks, which involve attention to qualities the experience represents, there exists a known object integration effect (Luck and Vogel in Nature 390(6657):279–281, 1997). I formulate a hypothesis I call “the turn-off hypothesis,” according to which this effect does not exist in change detection tasks where subjects are instructed to attend to mental paint. I argue that, given AS, we have some reason to expect the turn-off hypothesis to be true, but given AT, we do not. Consequently, the truth of the turn-off hypothesis would support AS. I further argue that one can straightforwardly test the turn-off hypothesis, taking the standard change detection paradigm and instructing participants to attend inwards.

Source: Luck and Vogel (1997), with permission from Nature Publishing Group

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I am grateful to Hilla Jacobson for advising me to focus on AS rather than merely on attention to mental paint.

Block (2003) claims we can attend inwards: he explicitly says that one can “attend to [mental paint] and be aware of it even when one is not attending to it” (p. 173). He also claims we can attend outwards in considering the transparency of experience, “which may be defined as the claim that the effect of concentrating on experience is simply to attend to and be aware of what the experience is of. As a point about attention in one familiar circumstance—for example, looking at a red tomato—this is certainly right.” (p. 171).

This point was stressed to me by Hilla Jacobson and Zohar Bronfman.

This claim is slightly inaccurate since Block (2003) distinguishes between mental paint and mental oil. The difference is that the former is representational, as in being a vehicle of content (see discussion below), whereas the latter is not. In this paper I focus only on the former.

Throughout the paper, I will assume physicalism, which I believe helps make the discussion more tractable (for example, it helps clarify the idea of a “vehicle”). The assumption is unproblematic in the present context because the mental paint view is compatible with physicalism, as is evidenced by the fact that Block, Loar, and Papineau are leading defenders of the latter.

Aside from identifying mental paint with vehicles of experiences, Papineau considers the possibility that mental paint is a functional property of experiences. For convenience, throughout the paper, I focus on the former approach, but what I say straightforwardly applies to the latter.

Prinz does not explicitly say whether he means attending to the content of the representation or to its vehicle. However, he endorses Fries et al. (2001) work, which suggests that, like Fries, he means attending to the content.

If our experience were to represent mental paint, then the phenomenology of the experience would be exhausted by its representational content, as intentionalists hold.

This assumption appears to be a truism (see Burge’s quote above, my discussion of the neuroscience of attention in Sect. 5, and Papineau 2014, pp. 26–27), but there is a complication. While Papineau (2014, pp. 26–27) grants that, usually, we are aware of qualities our experience represents, and not of mental paint, he denies this for cases of hallucination or illusion. His point is that we cannot be aware of qualities that are not instantiated in our vicinity; we cannot be aware of merely represented qualities, in other words. Assuming this point about awareness carries over to attention, it seems that Papineau would deny that, in cases of hallucination and illusion, we can attend to qualities our experience represents. So he would not accept AS for cases of hallucination and illusion, but he would accept it for cases of veridical perception, or so it seems.

While Burge and Loar clearly say we can attend to mental paint, Kind sometimes says we can be aware of mental paint, without explicitly mentioning attention. Papineau never explicitly says we can attend to mental paint, only that we can be introspectively aware of it. However, the way Kind and Papineau discuss the matter makes it clear that they are not speaking about awareness without attention (see below). For, they are speaking of a sort of awareness that gives rise to thoughts about mental paint, and arguably we cannot form thoughts about mental paint, on the basis of our awareness of it, without attending to it.

This claim is slightly inaccurate. During the blank screen stage, one directs attention to the content of a representation in visual working memory, not to the content of a conscious visual experience. So it is not accurate to say that, during that stage, one is attending to a quality one’s experience represents. A more accurate formulation is that, during that stage, one directs attention to a feature the experience had represented before it disappeared.

If the reader thinks that (in vision) there is no orientation mental paint (and more generally no spatial mental paint), only color mental paint, then it is possible to modify the experiment so that it will include only colors. Specifically, it will include conjunctions of colors, in the form of a square within a square (e.g., a red square within a green square), as in one of Luck and Vogel’s (1997) experiments. The participants will be instructed to attend only to color mental paint in all tests, ignoring orientation.

For a similar formulation of the method see Loar (2003, p. 91).

Thanks to Takuya Niikawa and Wayne Wu for discussions of Loar’s method.

Clarification: it is possible to form a judgment about more objects than working memory can contain. In that case, however, one keeps in working memory only statistical properties, e.g., average orientation or frequent color (Treisman 2006). Such a statistical memory is of no help in most change detection tasks (depending on their design).

Thanks to Hilla Jacobson and Angela Mendelovici for raising concerns of broadly this sort.

I thank Zohar Bronfman for raising a concern along these lines.

A minor complication: if Prinz is correct in claiming that consciousness requires attention, then VEH1 is red mental paint only when it is gamma synchronized. So, strictly speaking, VEH1 is not, in and of itself, red mental paint. Instead, gamma synchronized VEH1 is red mental paint. This complication does not matter to the central point I make in what follows.

References

Baars, B. J. (1988). A cognitive theory of consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Block, N. (1990). Inverted earth. Philosophical Perspectives, 4, 53–79.

Block, N. (2003). Mental paint. In M. Hahn & B. Ramberg (Eds.), Reflections and replies: Essays on the philosophy of Tyler Burge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Burge, T. (2003). Qualia and intentional content: Reply to block. In M. Hahn & B. Ramberg (Eds.), Reflections and replies: Essays on the philosophy of Tyler Burge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Campbell, J. (2002). Reference and consciousness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carruthers, P. (2015). The centered mind: What the Science of working memory shows us about the nature of human thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dehaene, S., & Naccache, L. (2001). Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: Basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition, 79(1–2), 1–37.

Fries, P. (2005). A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: Neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 474–480.

Fries, P., Reynolds, J. H., Rorie, A. E., & Desimone, R. (2001). Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science, 291(5508), 1560–1563.

Gazzaley, A., & Nobre, A. C. (2012). Top-down modulation: Bridging selective attention and working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(2), 129–135.

Harman, G. (1990). The intrinsic quality of experience. Philosophical Perspectives, 4, 31–52.

Johnson, J. S., Hollingworth, A., & Luck, S. J. (2008). The role of attention in the maintenance of feature bindings in visual short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 34(1), 41–55.

Kind, A. (2003). What’s so transparent about transparency? Philosophical Studies, 115, 225–244.

Kind, A. (2008). How to believe in qualia. In E. Wright (Ed.), The case for qualia. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kuznetsova, A. Y., & Deth, R. C. (2008). A model for modulation of neuronal synchronization by D4 dopamine receptor-mediated phospholipid methylation. Journal of Computational Neuroscience, 24(3), 314–329.

Lamme, V. A. F. (2003). Why visual attention and awareness are different. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(1), 12–18.

Loar, B. (2003). Transparent experience and the availability of qualia. In Q. Smith & A. Jokic (Eds.), Consciousness: New philosophical perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luck, S. J., & Vogel, E. K. (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390(6657), 279–281.

Mendelovici, A. (2014). Pure intentionalism about moods and emotions. In U. Kriegel (Ed.), Current controversies in philosophy of mind. New York: Routledge.

Papineau, D. (2014). Sensory experience and representational properties. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 114(1), 1–33.

Prinz, J. J. (2012). The conscious brain. New York: Oxford University Press.

Treisman, A. (2006). How the deployment of attention determines what we see. Visual Cognition, 14(4–8), 411–443.

Tye, M. (1995). Ten problems of consciousness. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Tye, M. (2002). Representationalism and the transparency of experience. Nous, 36(1), 137–151.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Hilla Jacobson, Angela Mendelovici and Zohar Bronfman for providing excellent criticisms and suggestions when the core idea of the paper was in its infancy. Thanks to Ori Beck for multiple discussions of the entire manuscript. Thanks also to Amir Horowitz, Takuya Niikawa, John Schwenkler, Miguel Angel Sebastian, Ran Weksler, Wayne Wu, and an anonymous referee for Philosophical Studies for helpful feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weksler, A. Attention to mental paint and change detection. Philos Stud 174, 1991–2007 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0784-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0784-2