An expert on the social and cultural implications of technology responds to Aliza Greenblatt’s “If We Ever Make It Through This Alive.”

Aliza Greenblatt’s “If We Make It Through This Alive” is an immediately engaging story, but the deeper in you get, the more is revealed. And one of the starkest but most subtly played revelations comes near the very end, when the audience is confronted with twin harsh truths: Disabled and otherwise marginalized people are least often thought of when planning for the future—and what disabled people know from their experience of living in this world likely makes them better prepared than nondisabled people to survive whatever comes next.

In my work, I look at how the values of human beings make their way into technology, and what happens when they do. I am also a queer, neurodivergent Black man, and my life experience has led me to ask how we can be more careful and intentional about exactly what values we want to put into the technological tools and systems we make. Because our values are going to wind up in there, whether or not we’re careful, and the harm they can do is real and deadly. For instance, I’ve worked on projects which both explore the failures of disability technologies and seek to present a better, more disability-focused way forward.

For the past decade, my primary research question has been, “How can marginalized people be better positioned to use their experience and knowledge to reduce or eliminate tech’s most dangerous outcomes?” And it’s this question I saw reflected in the culmination of Greenblatt’s story.

What seems to start as an account of a contemporary XPrize–style road-race is quickly shown to take place in a context where the “typical December day” in Pennsylvania is “warm and sunny.” Greenblatt’s protagonists, each with her own reasons, are all working on this cobbled-together car to get to the other side of the country, claim a very large cash prize, and prove something crucial, to themselves and the world. Sabrina, Jody, and Fern all have pasts they’re trying to confront or repair, and futures they’re trying to construct, and they’re doing it all in the ongoing, slow-moving apocalypse of the climate crisis.

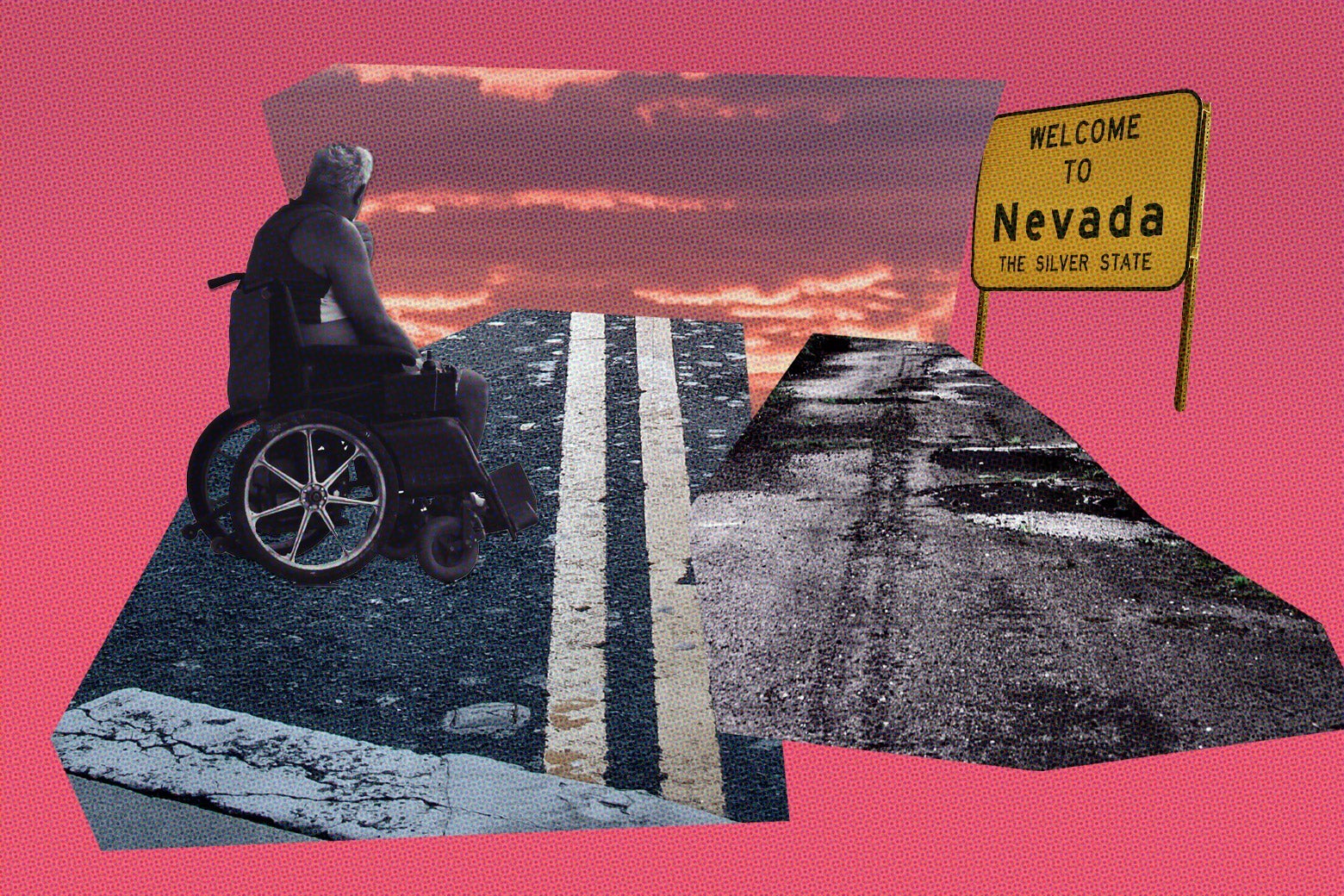

As they travel, they confront the swollen banks of the Mississippi River, the overbearing heat along the road, the maintenance needs of their bodies and their vehicle, and everywhere, the cracked and broken asphalt and eroded banks of roads with bushes and trees growing right up in the middle. When the road collapses under them in Nevada—so close to the end of the race!—their battery is crushed, and with it their hopes of finishing.

Enter Edan, a helpful stranger atop what “looks like a rusted, hollowed out Ford four-wheel drive being pulled by two Robomules,” something with all-terrain capability and maneuverability well beyond any of the cars and trucks in the race. Edan tows them back to his place to let them rest up and figure out what to do next— and then he sits in his wheelchair and gets comfortable for the night.

In this one moment, Greenblatt recasts the entirety of what we’ve read thus far and forces us to ask fundamental questions. What must this world be like if a wheelchair user finds living in mountainous terrain and engineering a robotic carriage to traverse broken asphalt preferable to living in a city? And Greenblatt takes it further when Fern asks Edan why he doesn’t take his obvious skills and get a job in a major city. Edan replies, “I tried, but these refashioned cities did a crap job designing for wheelchairs.”

The stories we tell ourselves about climate resilience and adaptability have tended to imagine the cities of the future will be shiny and perfect, with swooping curves and gleaming mergers of the organic and the mechanical. “If We Ever Make It Through This Alive” forces us to recognize that these visions of the future rarely, if ever, account for the lives and needs of disabled and otherwise marginalized people. And that’s because, quite frankly, the cities and societies we have today aren’t doing too great a job of it, either.

The maintenance of our pavement is so important for anyone with mobility disabilities that it is written into disability access laws. But potholes, cracked concrete, and roots going through the sidewalks of any given neighborhood demonstrate that those laws are so often ignored that there continues to be a need to press their enforcement. The needs of disabled people have been literally encoded into federal law for 32 years (a shockingly short period of time), and yet remain so blatantly disregarded that people have to sue for accommodations.

Not only that, but as we’ve continued through the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve repeatedly been confronted with calls to ration care, or with statements from the general public and even public health professionals that we shouldn’t be worried because it’s “just” the people with comorbidities who are at the highest risk for hospitalization and death. So it’s not at all hard to believe that future American cities needing to reshape themselves in order to handle vast swaths of climate crisis refugees would choose to ignore disabled people first and foremost.

Anyone who recovers from COVID-19 or who gets “long COVID” faces increased likelihood of permanent neurological changes, decreased respiratory response, and increased chances of heart attack and stroke—probably for the rest of their life. Conditions which will be exacerbated as the world gets hotter and dustier, and as new (or very old) diseases come onto the scene. Disabled people could have led the way to keeping us all safe during this pandemic, and multiple chronically ill and otherwise disabled people have written guides on how to survive lockdowns, trying to get the general public to understand the toll on mental health and well-being that was on the horizon. It’s all the more galling because there’s a high likelihood that, given time and circumstances, we’ll all be disabled one day.

When nondisabled people think about the needs of disabled people at all, it’s generally in the context of innovations that “mean well” but end up just being what Liz Jackson—a founding member of the Disabled List, a design firm—calls a “Disability Dongle.” But the perspectives and lived experiential knowledge of disabled people have been ignored at best; more often, their lives are relegated to “acceptable casualties.” In Western society, people have spent decades and centuries advocating for eliminating disabilities all together—usually starting with eliminating disabled people. These eugenicist modes of thought persist and recur, even into visions of the future like those of transhumanism, where thinkers can envision changing the human body into that of an angel but still fail to imagine a bathroom stall wide enough for the wings.

So what would better civic and architectural planning look like? It includes things like the addition of subtitle tracks to public video announcements, the inclusion of Braille on all products in stores, and prioritizing lifts, ramps, curb cuts, and railings instead of stairs. Many of these innovations, and others like tactile directional arrows on buttons and auditory cues on crosswalks, already exist but need to be more widely used. Designing for disability means increasing the adaptability and multipurpose frameworks of the built environment—but it also means recognizing that some access solutions will conflict with others.

When the small ramps from the sidewalk to the street known as curb cuts are in place, they can be a massive help for people with mobility disabilities, such as wheelchair or crutch users or even people who just have difficulty taking steps up or down. But those same curb cuts can present a hazard for blind and low-vision pedestrians who no longer have the curb as a clear signal for the difference between “sidewalk” and “street.” To that end, tactile paving was developed—plates of knobbly bumps that feel different both under the feet and at the end of a white cane. And yet that very same innovation doesn’t have a set width, so the wheels of chairs and the feet of canes and walkers can sometimes encounter the bumps in harmful ways.

The fact is, there’s no one-size-fits-all, “universal” design solution to magically accommodate all disabled and nondisabled users. But, more often than not, considering the needs of disabled people and providing a range of access solutions will result in increased access, across the board.

Heeding disabled people’s recommendations about social and physical infrastructures can also provide us with the tools to survive what is already happening, right now. Everyday choices disabled people have to make can, in fact, be the difference between life and death. Disabled people know how to strategize to share scare supplies of medication and resources. Disabled people have had to learn how to do maintenance and repair on the technologies they need to survive. Disabled people know the value of community organizing and community care.

Disabled people know these things because disabled people have had to learn how to do and provide these things for themselves and each other, and to navigate the hostile systems of a world which consistently refuses to adapt to disabled peoples’ needs. What better sets of skills and lived, experiential knowledge could we have as the world collapses around us?

“If We Make It Through This Alive” gives us a vision of the future America where people have to navigate and adapt to suddenly and persistently inhospitable and even deadly environments and social relationships, every single day. An ongoing climate apocalypse where the struggle for survival is turned into a game and those who play it condescendingly lauded as “inspiring,” rather than just recognized as doing what it takes to live in a world that refuses to accommodate them. For many disabled and otherwise marginalized people, this picture is immediately and intimately familiar in this present moment.

Here, today, I still hold out hope that we’ll figure out that we need to heed and empower marginalized people whose life experiences and understandings can help change our societies into ones where everyone can survive and thrive in the world to come.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.