- 1Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

- 2Department of Health Sciences, University of Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy

Violence against women is a growing health problem, especially when perpetrated in intimate relationships. Despite increasing attention, there is little comparative evidence on the different types of violence involved and there is a paucity of research on sexual femicides. This study examines cases of violence against women in northern Italy, focusing on sexual and non-sexual femicides and comparing them with rape that does not result in femicides. The sample included 500 women who were victims of sexual and non-sexual femicides, and of rape. Results show sexual femicides mostly involved unknown victims or women who were prostitutes. Sexual femicidal offenders used improper weapons to kill their victims, acted in secluded locations, and fled the crime scene; their crime was more likely the result of predatory intentions, with antisociality and sexual deviance being the most significant factors related to this type of femicide. The criminal and violent pattern that characterized sexual femicides in this study shared significant similarities with the pattern of violence involved in rape. Rape victims were in fact mostly unknown, or involved in a brief relationship with their killer. When the victim was known it was more likely that the abuse occurred at home and in front of the woman’s children. Rapists were often under the effect of alcohol or drugs. Non-sexual femicides mainly involved known victims, and they were more often committed in the context of domestic disputes. It was not seldom that the long relationship between the victim and perpetrator was likely to be characterized by contentiousness, suggesting that the woman was often victim of an oppressive climate of emotional tension and domination. Morbid jealousy contributed to aggravating the tone of a controlling relationship. Non-sexual femicides bore more similarities to cases of rape within the pattern of intimate partner violence. Findings are discussed in terms of their implications for prevention and intervention.

Introduction

A major public health problem and human rights violation plaguing humanity is violence against women (hereafter abbreviated as VaW) (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). VaW takes different forms (emotional, sexual, psychological, physical, economic, and cultural) that vary in frequency, intensity, and severity (Marks et al., 2020). It also differs according to types (known or strangers) and number (single or multiple) of victims involved (Zara et al., 2019, 2021) and the nature of the relationships (intimate, familiar, acquaintance or superficial vs. no relationship) between victims and perpetrators (Gino et al., 2019). It is not uncommon for victims to be in serious danger of losing their lives (Matias et al., 2020) i.e., femicide. Femicide is a violation of the basic human right to life, liberty, and personal security (Russell and Harmes, 2001).

Despite a lack of reliable data making it difficult to estimate the true extent of VaW aggravating into femicide, the most consistent research finding across the world is that only a small proportion of femicide occurs within an anonymous setting (Zara and Gino, 2018). According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2021), on average, every 11 min a woman is killed by someone she knows; often it is someone in her own family, someone with whom the victim had an affective and/or intimate relationship. In most cases, such a killing is the culmination of previous experiences of various forms of violence, including sexual violence, perpetrated against them.

The sexual component of violence against women (e.g., rape) deserves special attention in so far it would lead to a more comprehensive understanding of those cases in which women are predominantly raped but not killed, those cases in which the rape occurs later and in a context of an oppressive, abusive and domineering relationship, and those cases in which women are also killed before, during or after being sexually abused. Notwithstanding that literature on femicide has grown in recent years, specialized studies on sexual femicide are still limited and within the general conceptual framework of sexual homicide (Chan, 2017).

According to the United Nations, VaW is one of the least prosecuted and punished crimes in the world. Although it is extremely difficult to compartmentalize violence into discrete events, an understanding of the psycho-criminological factors that anticipate the occurrence of femicide (sexual and non-sexual) and of rape is essential for scientific and clinical reasons, but above all for preventive purposes, that is, also to prevent the pejorative transformation of violence into femicide. The multidimensional offensive pattern of rape includes sexual violence that is intertwined with intimate partner violence (rape within IPV) (Campbell et al., 2003; Spencer and Stith, 2020) or sexual violence per se (rape ‘only’) (Veggi et al., 2021).

The following pages describe these forms of violence against women: sexual and non-sexual femicides, each compared with rape.

At the first level of analysis, the primary focus brings together some of the worst and most extreme aspects of VaW by examining whether and to what extent sexual and non-sexual femicides are similar or different, and whether they share more similarities or differences with rape.

At the second level of analysis, the focus is more specifically on sexual and non-sexual femicides compared with rape that occurs within IPV and rape ‘only.’

The shadow of sexual violence

Sexuality is the most intimate dimension of life (Zara, 2018) and its respect is paramount for the well-being of the person. It follows that the violation of sexuality is one of the most offensive forms of violence against a woman with long-term consequences upon her psychological, relational and physical health. It offends her as a person. It mortifies her sense of self because it deprives the victim of any choices of when, how, and with whom to share her search for intimacy and for pleasure (Tarzia, 2021).

Clinical findings on women who survived IPV show that abused women are rarely keen to share sexually abusive incidents unless specifically asked about them (Heron et al., 2022). According to Walker (1994, 2009), it seems that the sexual component of the abuse experienced by women is recounted as the worst in terms of both humiliation and physical pain. These findings are in line with what partially emerges (or cannot emerge) from statistics1 : the dark number behind rape and sexual assault is extremely high and this is testified by their low report rates (Truman and Morgan, 2018). Unacknowledged rape is a quite common phenomenon not only among college women (Littleton et al., 2007) but among women survivors in the community (Harned, 2005), who do not label their experiences as rape but instead use more benign labels, such as «miscommunication» or «bad sex» (Wilson and Miller, 2016). The sexual script (Masters et al., 2013) adopted in such circumstances acts as a copying mechanism, mostly soon after the event, when confusion is still the main sensation that obliterates awareness of what had really happened (Kahn et al., 2003).

Studies show that unacknowledged rape is more likely to occur when the perpetrator is known, often in an intimate and romantic relationship with the woman (Littleton et al., 2018), in a setting in which abuse of alcohol or binge drinking has altered any sense of control (Peterson and Muehlenhard, 2011), and in which the woman often declares that she did not engage in a clear resistance strategy (Cleere and Lynn, 2013). Taken together these findings reveal that a sexualized offense is experienced as an amplified trauma in which not a single part of the victim was left untouched. Studies also suggest that when rape occurs within a relationship it is more likely that it is embedded in a broader pattern of abuse and violence (Coker et al., 2000; Matias et al., 2020; Sardinha et al., 2022). Rape that escalates into femicide, i.e., sexual femicide, is a type of VaW of a relatively rare occurrence (World Health Organization [WHO], 2012). However, its impact is extremely destructive.

Sexual and non-sexual femicides

Sexual femicides

If the term femicide refers to the killing of women by men because they are female, the term sexual femicide refers to the extreme form of control in which sex is used to degrade them to the point of death. The nature of the relationship between victim and perpetrator tells how and why the victim is killed. Table 1 presents a description of all these forms of violence that are the objects of this study.

There is a dearth of specific studies on sexual femicide, and most investigations focus on sexual homicide (Chan, 2017). The use of sexual violence in the form of rape is an extreme form of control against a woman and sexual femicide is considered the most misogynistic form of violence in which a woman is reduced to a sexual commodity or a mere object of control, who once sexually used, could be thrown away (Horley and Clarke, 2016). Therefore, sexual femicide becomes the criminogenic setting where VaW can be explored in its boldest form, because the final gesture of femicide combines, in the act of killing, sexualized aggression, contempt, entitlement, predatory attitudes, psychological and physical domination, and vindictive interests (Salfati and Taylor, 2017).

To understand what distinguishes lethal from non-lethal sexual assaults and whether sexual killers constitute a distinct group of sex offenders, Stefańska et al. (2015) compared sexual killers to sex offenders (specifically offenders involved in rape or attempted rape). Overall, these groups had more similarities than differences (Stefańska et al., 2015).

According to Beauregard and Martineau (2016), sexual murderers seem to have similar characteristics (combination of deviant sexuality and antisociality) to violent, non-homicidal sex offenders, defined as individuals involved in a heterogeneous criminal career (Merlone et al., 2016; Zara and Farrington, 2016) but also primarily preoccupied with sex (Zara et al., 2019).

As suggested by Carter and Hollin (2014), it might be relevant to place the offense in a situational context to understand whether the killing and the sexual element of the violence are directly or indirectly related. When they are directly linked, the act of killing is itself sexually gratifying, or the killing facilitates sexual acts on the victim’s body at the time or following the killing. When the killing is indirectly linked to rape, the killing is not a source of sexual arousal or stimulation but is an extreme reaction to restore control (e.g., the victim is killed because she is trying to escape or end the relationship).

Despite the rich attempts to establish a comprehensive set of criteria to define sexual killing (Ressler et al., 1988; Chan, 2015; Carter et al., 2017), little is known about what makes a femicide sexual and what makes femicidal sexual offenders distinct from non-femicidal sexual offenders. The latter could be a form of hate crime that requires specific scientific, social, cultural, and clinical attention.

Burgess et al. (1986) were among the first to attempt to classify sexual homicide and to distinguish sexual homicide from simply a homicide resulting from a sexual assault. They maintained that sexual homicides “result from one person killing another in the context of power, control, sexuality, and aggressive brutality” (p. 252). Häkkänen-Nyholm et al. (2009) emphasized that most of the victims of sexual homicides are female.

A widely used definition of sexual killing based on physical evidence at the crime scene or in forensic records is that of Ressler et al. (1988). For a killing to be considered sexually motivated, at least one of the following criteria must be met: (1) the victim lacks clothing; (2) the victim’s genitals are exposed; (3) the body was found in a sexually explicit position; (4) an object was inserted into the victim’s body cavity (anus, vagina, or mouth); (5) there is evidence of sexual intercourse (oral, vaginal or anal); (6) there is evidence of substitutive sexual activity (e.g., masturbation and ejaculation at the crime scene, or body exploitation) or sadistic sexual fantasies (e.g., genital mutilation).

Holmes and Holmes (2001), simplified the classification, and defined sexual homicide as the combination of lethal force with a sexual element.

Chan (2015, p. 7) added to the previous classification two new criteria: (1) a legally admissible admission by the offender regarding the sexual motive of the crime that intentionally or unintentionally results in homicide; (2) an indication of sexual elements of the crime from the offender’s personal effects (e.g., home computers and diary entries).

Salfati (2000) differentiated types of homicide based on their behavioral nature found at the scene, and on the dual model of aggression by Feshbach (1964): expressive and instrumental aggression. Expressive (or hostile) aggression typically occurs in response to circumstances that trigger anger, with the intention of making the victim suffer. In contrast, instrumental aggression results from a desire to acquire objects or status (e.g., valuable items, control, and territory) regardless of the cost. This distinction suggests that expressive aggression may more likely be exercised against known victims, whereas instrumental aggression may more likely be exercised against unknown victims.

Non-sexual femicides

Non-sexual femicides is characterized by violence that escalates into a lethal epilog. Studies show that non-sexual femicide includes some or all of the following characteristics: threatened physical or sexual violence, economic and cultural violence, and emotional or psychological abuse perpetrated by a man (usually known) to the victim. In most cases, the perpetrator is a current or former intimate partner (Campbell et al., 2007; Neppl et al., 2019; Marco Francia, 2021; Zara et al., 2022). Perhaps, it is the shared history between victim and perpetrator that makes this type of violence escalate to femicide.

Skott et al. (2018) compared sexual femicides2 with non-sexual femicides in Scotland (United Kingdom). In their study, they examined data from a national police database and compared 89 male sexual femicidal offenders who had killed adult women with 306 male non-sexual femicidal offenders who had also killed adult women. The sexual femicides in their sample appeared to be more likely associated with instrumental aggression and sexual deviance, making sexual femicidal offenders more comparable to sex offenders than to other femicidal offenders.

In a study by Langevin et al. (1988) it was found that victims of non-sexual femicide tended to be older than the two sexual groups, and that sexual femicidal offenders were more likely to attack a female victim compared with non-sexual femicidal offenders. Examining sexual and non-sexual femicidal offenders they have found many differences between these criminal career groups (Langevin et al., 1988).

If sexual femicide differs from non-sexual femicide in terms of victims and perpetrators, this could have important implications not only for future research but also for policy, interventions, and rehabilitation programs for perpetrators.

Another study (Stefańska et al., 2020) suggests that sexual femicide could represent a hybrid offense combining rape and femicide. While rape may serve as a reminder of sexual proprietariness of a woman by a man (Wilson and Daly, 1993; Spencer and Stith, 2020), femicide may serve as the ultimate form of revenge for certain types of abusive and controlling personalities (Serran and Firestone, 2004). The combination of rape and femicide is the most prevalent form of sex-related killing (Geberth, 2016) intensified by the intimacy of the relationship (Geberth, 2018).

Given that several studies (Salfati and Canter, 1999; Salfati, 2000; Beauregard et al., 2018; Skott et al., 2018) have found more similarities than differences between sexual femicide offenders and rapists, it is plausible that sexual femicide should be considered an extreme variant of rape rather than a sexual variant of femicide.

Hence, according to Stefańska et al. (2021), understanding that hybrid should be the primary focus of psychological investigation.

This study

This study examines cases of violence against women in northern Italy, focusing on sexual and non-sexual femicides and comparing them with rape that does not result in femicide.

The aim is threefold. Firstly, to explore similarities and differences in femicides: femicides that include sexualized violence and femicides that are not sexualized. Secondly, to analyze types of sexual femicides and to explore whether certain factors are more likely involved in either sexualized or grievance femicides. Thirdly, to compare cases in which rape is acted out without the escalation into femicide with cases in which rape is also a key part of the femicide dynamic. The interest is to see the extent to which femicides, sexual and non-sexual, in Italy involve the same risk and criminogenic factors of other forms of violence against women such as rape.

According to our knowledge, this is the first time a comparative study of different forms of VaW (non-sexual femicide vs. sexual femicide vs. rape) was conducted in Italy. While we are aware that violence against women is rarely a discrete event, especially when the victim knows the perpetrator and has a relationship with him, as shown in other studies (Flynn and Graham, 2010; Davies et al., 2015), this study sheds light on the seriousness of any forms of violence above and beyond what is considered the most dramatic aspect of it: death.

Research questions

This study addresses the following questions:

(1) Are sexual and non-sexual femicides more similar or different in terms of victims, perpetrators, and characteristics of the exhibited violence?

(2) Are all sexual femicides of the same kind?

(3) What do sexual femicides have in common with rape?

(4) What do non-sexual femicides have in common with rape?

Materials and methods

Data collection and information for the study

The data used in this study were collected from a multisite project3.

The first phase of the study consisted in identifying the victims of femicide; information about age, profession, previous criminal records, prior involvement in violence, dynamics of the femicide; types of relationships between victims and perpetrators were also gathered.

Information on further exploitation of victims’ bodies and mutilation, as stated in the pathology reports, was collected. Forensic files from the Court of Turin were also examined, along with files from the archive of the medical experts who assessed the cases. This multisite study excluded all cases of women’s natural death or suicide.

In order to be able to explore differences between sexual femicides and rape that did not lead to the death of the victim, cases of sexual offending perpetrated by men against women, i.e., rape were examined.

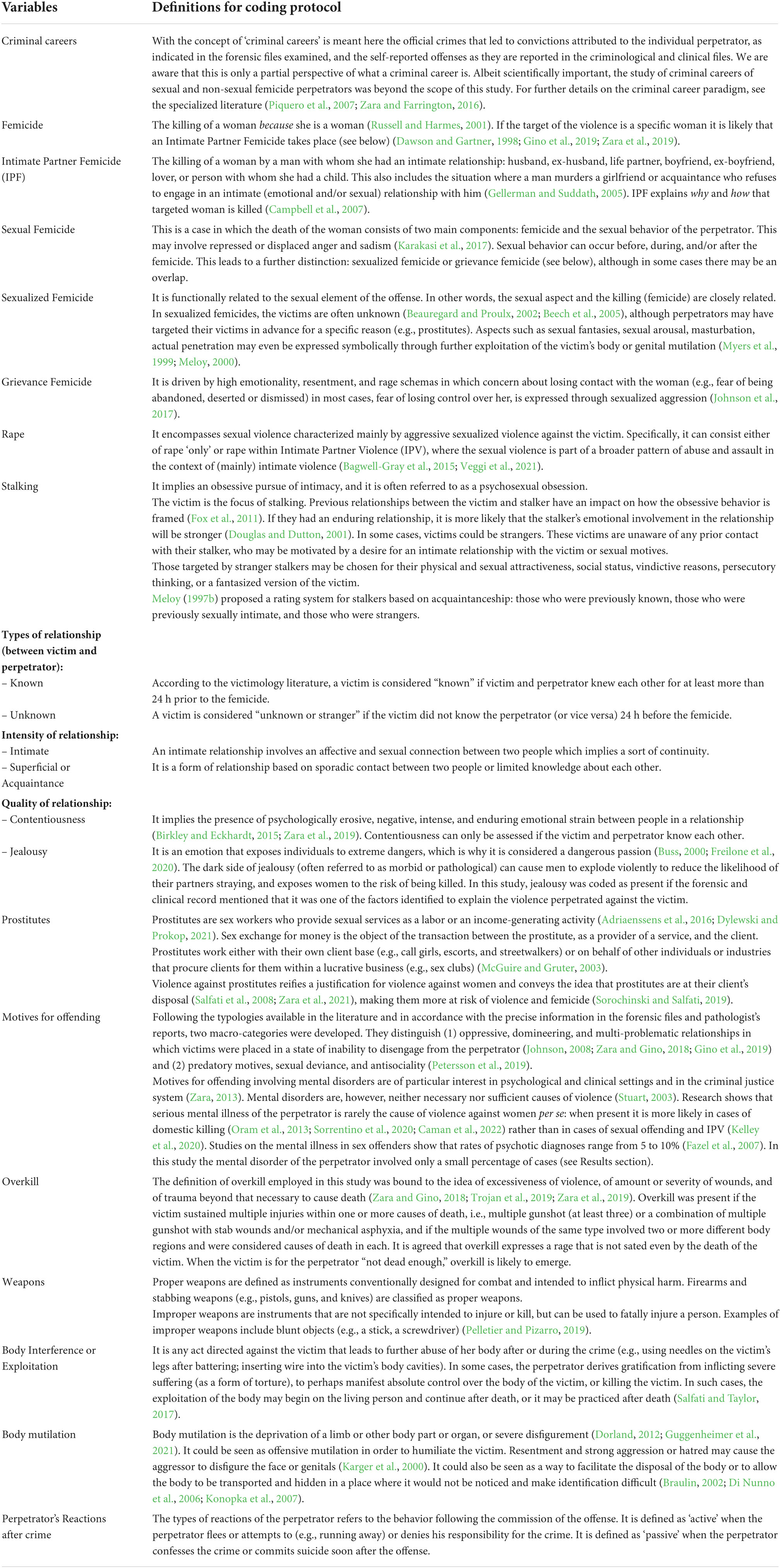

Variables

All information collected was classified according to the following dimensions: age, nationality and occupation of the victim and the perpetrator, location of the violence (e.g., at home: either in the victim’s or the perpetrator’s home; in a public place: usually in an isolated/secluded place in the outskirt of a city or town), medico-legal aspects of the murder (e.g., weapons used, substance abuse, i.e., alcohol and/or drugs, body mutilation and other forms of exploitation of the victim’s body), the perpetrator’s reaction after the crime (e.g., active vs. passive), the types of sexual femicides (e.g., sexualized femicide or grievance femicide). The type (known vs. unknown), intensity (intimate vs. acquaintance/superficial), duration of the relationship between victim and perpetrator (short- to medium-term vs. long-term), and the possible presence of children provided researchers with information to examine the context in which the crime occurred and to distinguish between sexual femicide, non-sexual femicide, and rape (see Table 1 for details).

In addition, contentiousness between victim and perpetrator and morbid jealousy were examined. These dimensions are relevant to assessing (1) the presence of violent incidents previously reported to the police, along with a pattern of frequent violent rows (contentiousness); (2) the dynamics of femicide and rape by examining the role of possessiveness, intrusive control, and obsessive desire for intimate exclusivity (morbid jealousy) in triggering the violence. In examining femicide, overkill (i.e., excessive force beyond what is necessary to cause death) was also considered.

Data coding

Variables related to victims and perpetrators (such as age, nationality, and profession), locations of crime (e.g., indoor or outdoor), and the medico-legal aspects of the offense (e.g., body exploitation) were directly extrapolated from the scientific and forensic material available. Variables related to the violence dynamics were coded by two independent judges. Coding protocols used to formulate each specific variable are extremely relevant for reconstructing the data into a coherent framework, to explain the meaning of each variable endorsed and to differentiate them. Behavioral variables were dichotomized (see later for the rationale behind dichotomization) into either present or absent. This procedure identified 18 variables related to victim-perpetrator relationships, motive, and context of violence, as well as the variable “criminal career” that is here measured by criminal history recorded in the forensic file.

Regarding the quality of the relationship, contentiousness implies the presence of negative, intense, erosive and enduring emotional strain between people in a relationship (Birkley and Eckhardt, 2015). According to Jordan et al. (2010), overkill is described as the excessive use of force that goes further than what is necessary to kill. It involves multiple injuries and results in one or more causes of death or multiple wounds distributed over two or more regions of the body (Salfati, 2003; Trojan et al., 2019).

Table 1 summarizes the variables explored, accompanied by the coding definition.

Body exploitation implies interferences with the body of the victim, either when alive (as in the case of sex offending) or once dead (as in the case of femicide). In some cases, the perpetrator derives gratification (including sexual arousal and satisfaction) from inflicting severe suffering. In such cases, the exploitation of the body may begin on the living person and continue after death, or it may be practiced after death (see Table 1 for a detailed description).

Body mutilation was based on the pathologist reports and was assessed as present (1) or absent (0). In line with the medical literature (Guggenheimer et al., 2021), mutilation was defined as the deprivation of a limb or another body part or organ, or severe disfigurement. This could be seen as offensive mutilation and is likely done to humiliate the victim. Resentment and strong aggression or hatred may cause the aggressor to disfigure the face or genitals (Karger et al., 2000). In such cases it could happen that the victim is not killed.

Regarding motives for killing, two macro-categories were developed according to the typologies available in literature that distinguish an oppressive, domineering and multiproblematic relational condition (coded as 0) (Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart, 1994; Johnson, 2008), and predatory motives, sexual deviance and antisociality (coded as 1) (Petersson et al., 2019).

In order to explore the extent to which sexuality was a key element of the killing when comparing victims, sexual femicides (Higgs et al., 2017) were operationalized into grievance femicides (coded as 0) and sexualized femicides (coded as 1). A femicide was coded as grievance when it was driven by high emotionality, resentment, and anger. A femicide was coded as sexualized when there was forensic evidence that it was functionally related to the sexual element of the offense (Beech et al., 2005) (see Table 1 for a detailed description).

Two independent raters carried out the categorization of data into the assessment of contentiousness, overkill, body exploitation, motives of crime, and grievance or sexualized femicide. Separate variables were created to indicate the presence (coded as 1) or absence (coded as 0) of assessed dimensions in each case. When a discrepancy emerged, the two independent raters discussed the case with the research group, and re-assessed it, until a better level of agreement was reached. The Cohen’s Kappa statistic (Cohen, 1960) provides a quantitative measure of the magnitude of agreement between observers that is corrected for chance, and it is appropriate for this type of data. The levels of agreement for the category of contentiousness (Cohen’s K was 0.98, p < 0.001), for the category ‘overkill’ (Cohen’s K was 0.98, p < 0.001), for the category of type of reaction by the perpetrator after the crime (Cohen’s K was 0.99, p < 0.001), for the category of type of body exploitation (Cohen’s K was 0.96, p < 0.001), for the category ‘motives of crime’ (Cohen’s K was 0.99, p = 0.001), for the category of sexual femicide (Cohen’s K was 0.97, p = 0.001) and for the categories of grievance and sexualized femicide (Cohen’s K was 0.98, p = 0.001), suggest a substantial inter-rater agreement coefficient for all of these variables (Viera and Garrett, 2005; McHugh, 2012).

Analytical strategy

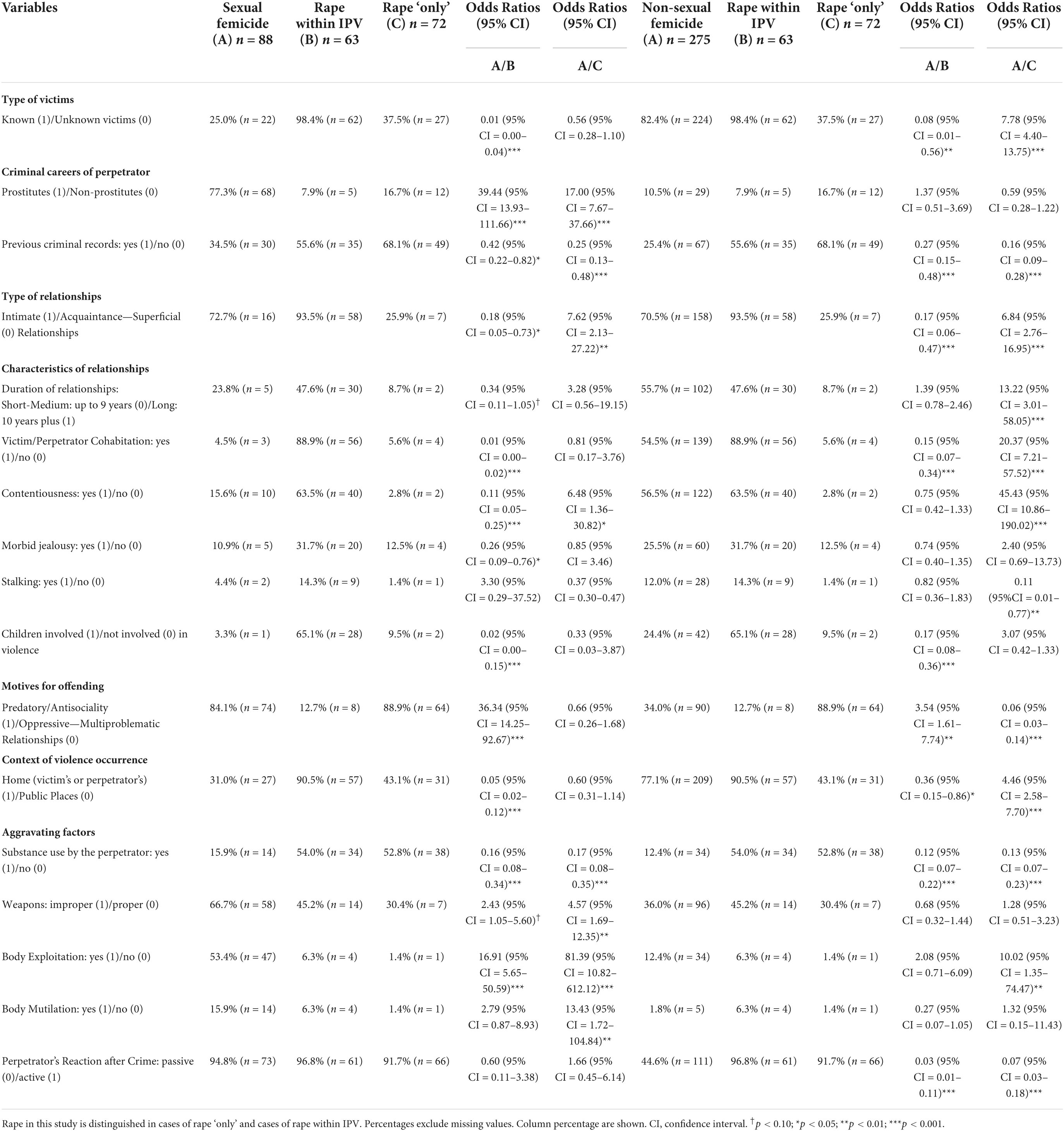

Descriptive and multivariate analyses with Odds Ratios (ORs) were carried out to explore specifically the characteristics of the sample involved and to provide an outlet for comparing: (1) sexual femicide and non-sexual femicide with rape; and (2) sexual femicide and non-sexual femicide with the subcomponents of rape: rape within IPV and rape ‘only.’

Specifically, 18 variables were examined and the OR was calculated to identify which of the 18 variables significantly and independently explained these types of violence. Also explored was whether the type of relationship between victim and perpetrator (known vs. unknown), and the intensity of the relationship (intimate vs. superficial/acquaintance) could affect the kind of violence the victim endured. The OR provides information about the existence, direction, and strength of an association between target and comparison groups regarding the likelihood of an event occurring (Farrington and Loeber, 2000). When ORs are higher than 1, situations characterized by that particular attribute have relatively higher odds of occurring than those that do not have that attribute (Zara and Farrington, 2020).

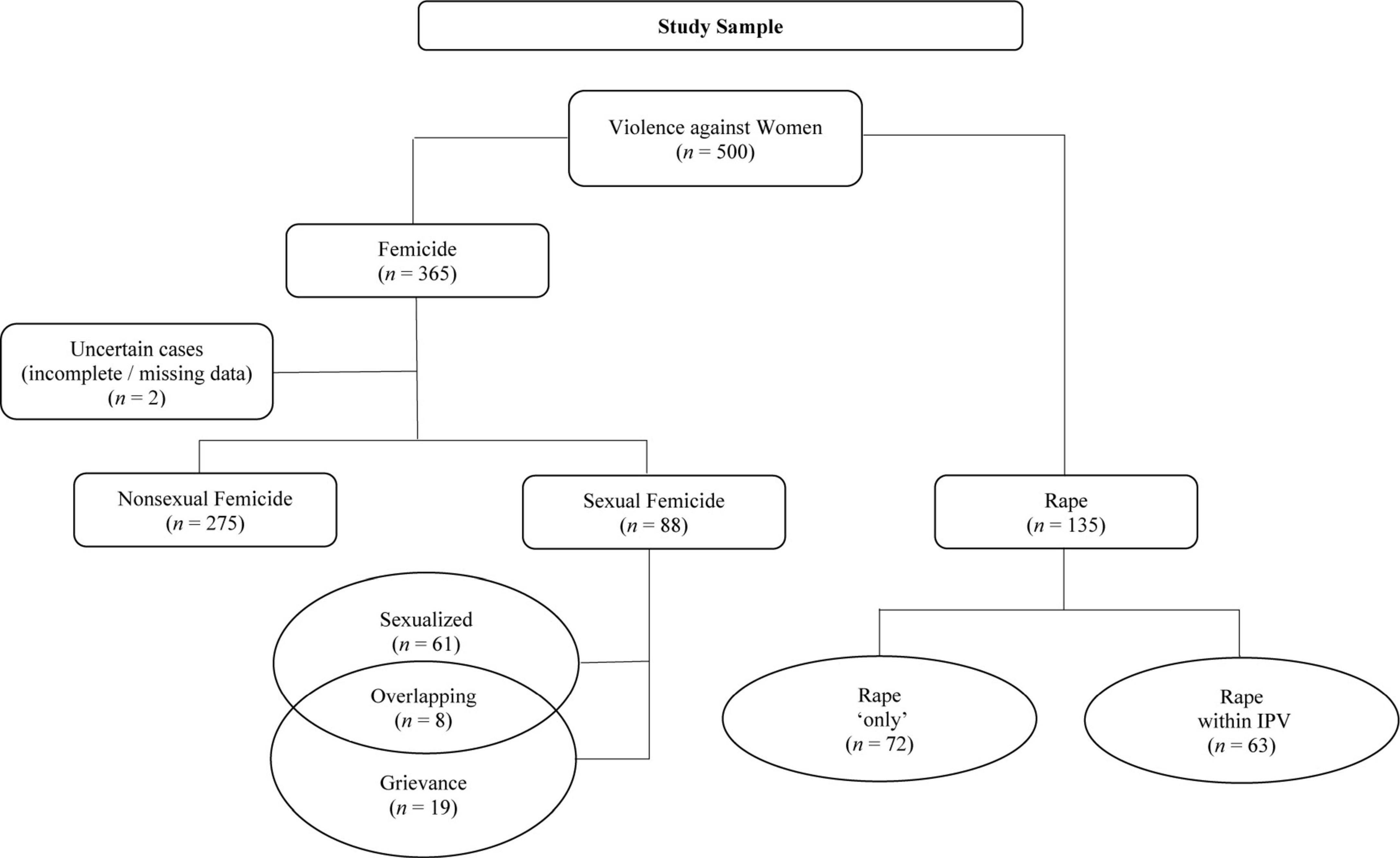

Sample

A total of 500 cases of VaW were selected and included in the sample. Specifically, the sample included 365 cases of femicide and 135 cases of rape. Figure 1 provides a detailed overview of the sample composition and distribution.

Perpetrators (n = 468) were on average 40.81 years old (SD = 15.65), mainly Italians (72.2%; n = 288) and employed at the time of the offense (64.2%; n = 235). Of them, more than a third had previous official criminal records (37.1%; n = 181). In only 6.1% of cases (n = 30) did the perpetrators suffer from a mental illness at the time of the crime, according to forensic psychiatric examinations.

In the present study, victims were also predominantly Italians (76.3%; n = 380) and professionally occupied (61.5%; n = 251). Victims were slightly older (M = 42.49 years old; SD = 20.16) than their perpetrators, but the difference was not significant, t(811) = 1.314, p = 0.09 (d = 0.09)4.

Table 2 summarizes the general information about the sample.

Perpetrators of sexual femicide were on average significantly younger (M = 34.45 years old; SD = 11.22) than perpetrators of non-sexual femicide (M = 45.10 years old; SD = 17.22), t(256) = 4.01, p < 0.001 (d = 0.65), while no difference emerged when compared with perpetrators of rape (M = 35.78; SD = 11.14), t(179) = −0.70, p = 0.49 (d = 0.12). Perpetrators of rape were significantly younger than perpetrators of non-sexual femicide, t(345) = 5.59, p = 0.001 (d = 0.62).

Victims of sexual femicide were younger (M = 34.16 years old; SD = 16.24) than victims of non-sexual femicide (M = 48.50 years old; SD = 20.53), t(360) = 5.98, p < 0.001 (d = 0.73). When comparing victims of sexual femicide with victims of rape (M = 30.40 years old; SD = 13.11), the former were slightly older than the latter, t(161) = 1.61, p = 0.06 (d = 0.25).

Victims of rape were also significantly younger than victims of non-sexual femicide, t(347) = 7.24, p = 0.001 (d = 0.94).

Results

This study explored similarities and differences in looking first at sexual and non-sexual femicides. It also explored more specifically types of sexual femicides and explored whether certain factors were more likely involved in sexualized rather than in grievance femicide and vice versa. It finally compared cases in which rape was perpetrated without the escalation to femicide with cases in which it was, instead, a key part of the femicide dynamic.

Findings suggest that 500 victims were either killed (n = 365) or raped (n = 135) by 468 perpetrators. Overall, the great majority of the victims were known (67.7%; n = 335) to the perpetrator, while in 32.3% of cases (n = 160) the victims were unknown. In five cases it was not possible to establish whether the victims were known or unknown.

When the victim and the perpetrator knew each other, in 71.3% of cases (n = 239) they were in an intimate relationship, characterized by emotional, affective and sexual involvement. On average the intimate relationship was nearly 13 years long (M = 12.62; SD = 13.11; Range: 0.01–24.13). In 53.5% of cases (n = 174) the relationship was characterized by contentiousness.

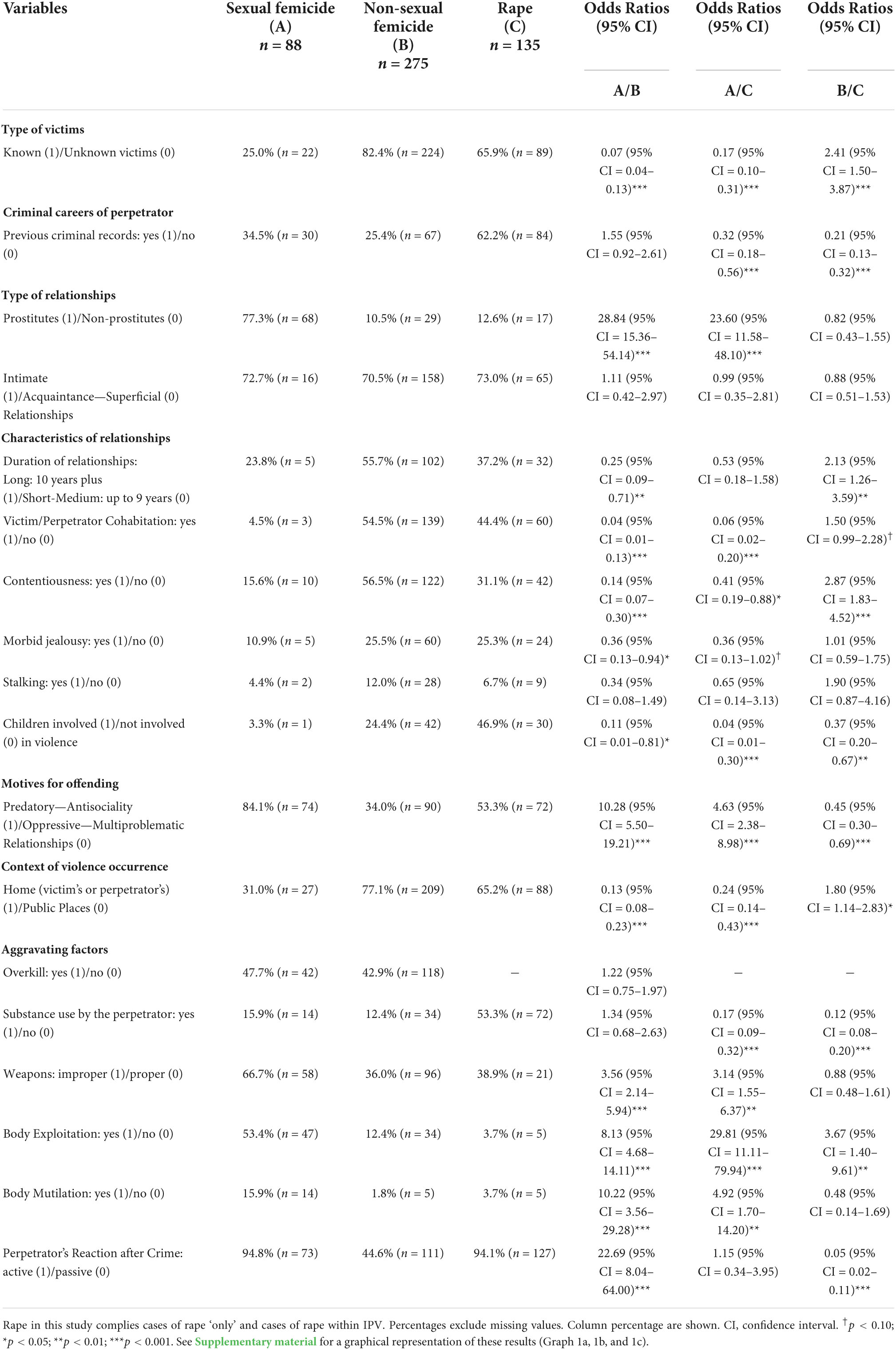

Comparing sexual femicide and non-sexual femicide

As shown in Table 3, the risk for women of being killed by a known perpetrator was lower in the case of sexual femicide (25.0%; n = 22) than in non-sexual femicide (82.4%; n = 224) (OR = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.04–0.13). When the victim knew the perpetrator, the intensity of the relationship with him (intimate vs. non-intimate, i.e., acquaintance/superficial) did not make any difference in how the woman was killed, either by a sexual femicide (72.7%; n = 16) or by a non-sexual femicide (70.5%; n = 158).

However, some differences emerged in the duration of the relationship. The relationship between the victim and perpetrator was shorter for sexual femicide than for non-sexual femicide5 (OR = 0.25; 95% CI = 0.09–0.71). The victim and perpetrator were less likely to live together (cohabitation) in the case of sexual femicide than in non-sexual femicide (OR = 0.04; 95% CI = 0.01–0.13), a finding that is consistent with the fact that sexual femicide was more likely to have occurred in public places rather than at home (OR = 0.13; 95% CI = 0.08–0.23). Looking at the quality of the relationship, contentiousness (OR = 0.14; 95% CI = 0.07–0.30) and morbid jealousy (OR = 0.36; 95% CI = 0.13–0.94) were less likely to influence sexual femicide than non-sexual femicide. No difference was found regarding stalking (see Table 3 and the Supplementary material for a detailed description of these results)6.

In sexual femicide, children were less likely to witness the violence than in non-sexual femicide, where children unfortunately witnessed the violence that led to their mothers’ femicide (OR = 0.11; 95% CI = 0.01–0.81).

When looking at the dynamic of violence, in sexual femicides it was more likely that the motives behind the violence were predatory or antisocial in comparison with non-sexual femicide (OR = 10.28; 95% CI = 2.14–5.94). It was more likely that sexual femicides occurred in a remote and secluded place in the outskirt of a city, in comparison with non-sexual femicides (OR = 0.13; 95% CI = 0.08–0.23). Perpetrators of sexual femicides more likely used an improper weapon (e.g., blunt objects) to kill in comparison with non-sexual femicides (OR = 3.56; 95% CI = 2.14–5.94), and also were eight times more likely to exploit the body of the victims even after the killing (OR = 8.13; 95% CI = 4.68–14.11). Furthermore, body mutilation was ten times higher in sexual femicide than in non-sexual femicide (OR = 10.22; 95% CI = 3.56–29.28). In sexual femicide perpetrators were more likely than in non-sexual femicide to escape after committing the crime (i.e., active reaction), in an attempt to avoid punishment (OR = 22.69; 95% CI = 8.04–64.00).

No difference was found in their criminal careers (e.g., previous criminal records) between sexual and non-sexual femicidal offenders (see Table 3 for details on these results).

Contrary to expectations, overkill per se was not significant in distinguishing sexual from non-sexual femicides. However, a separate analysis comparing known with unknown victims of femicide showed that the former (73.0%; n = 116) were at higher risk for overkill than the latter (54.7%; n = 130) (OR = 1.47; 95% CI = 0.94–2.32).

The psychology of sexual femicides

Of the 365 victims of femicides included in this study, 88 were women killed because of sexual femicide. For two cases of femicides it was not possible to establish whether the femicide was of a sexual nature or not.

Twenty-five percent (n = 22) of these victims were known to the perpetrator. As mentioned before, among these known victims, 72.7% (n = 16) had an intimate relationship with the perpetrator, although this relationship rarely lasted more than a decade (23.8%; n = 5) and only in a few cases (4.5%; n = 3) involved cohabitation between them (see Endnote 3). In 10.9% of cases (n = 5) the relationship was characterized by morbid jealousy and in 15.6% of cases (n = 10) by contentiousness. In only one case did sexual femicide occur in the presence of the victim’s children (3.3%; n = 1).

As shown in Table 3, in 77.3% of sexual femicides the victims involved were prostitutes (n = 68) in comparison with 10.5% of prostitutes (n = 29) in non-sexual femicides (OR = 28.84; 95% CI = 15.36–54.14) and with 12.6% of prostitutes (n = 17) in rape (OR = 23.60; 95% CI = 11.58–48.10). No significant differences emerge when comparing non-sexual femicides with rape.

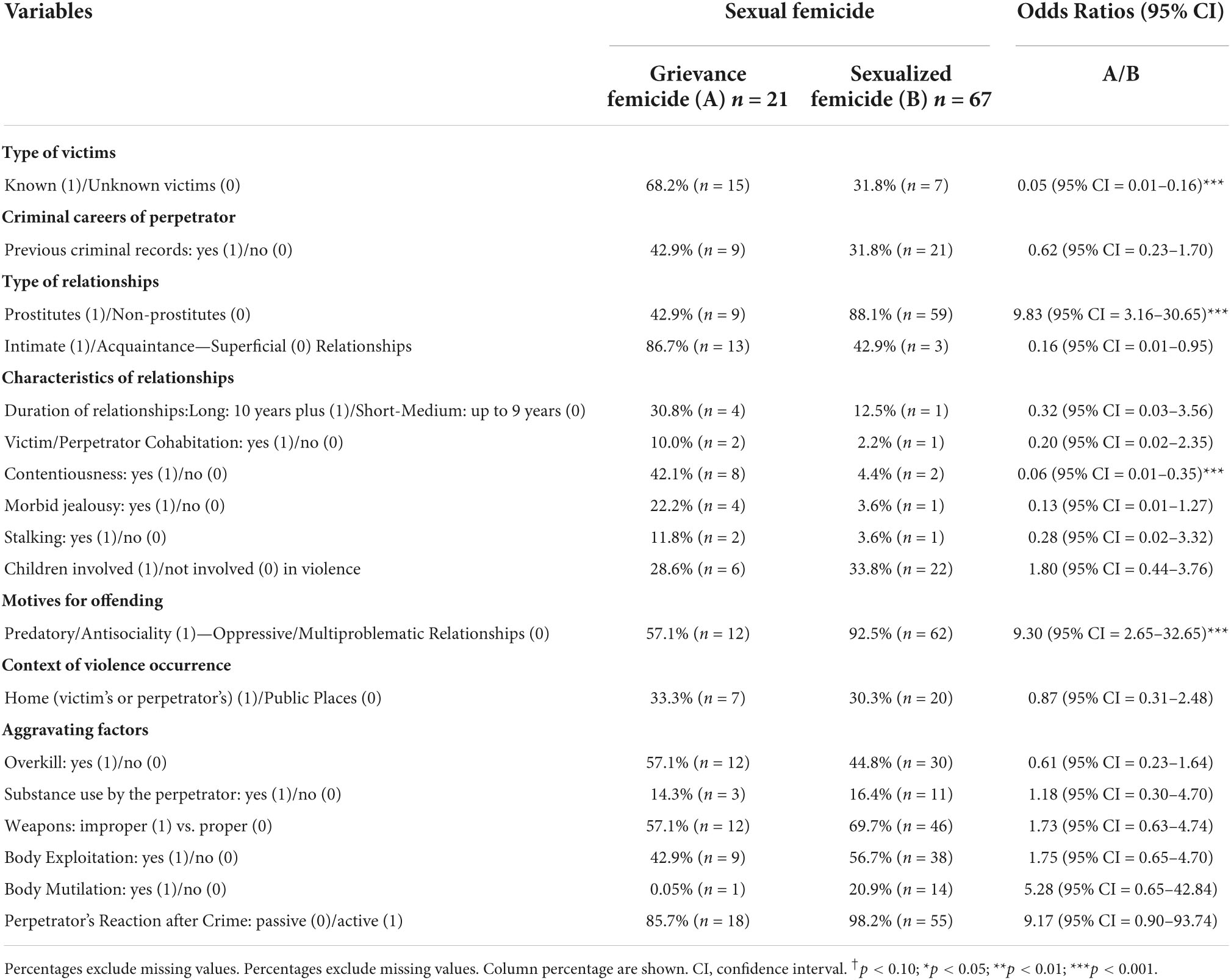

Are all sexual femicides of the same kind?

Looking specifically at the types of sexual femicide, we found that the vast majority of cases were sexualized femicides (76.1%; n = 67), while 23.9% (n = 21) were grievance femicides. Table 4 shows these results.

In 8 cases it was possible to identify an overlap between sexualized and grievance characteristics, albeit with a prevalence of characteristics typical of one or the other category. Although only involving a few cases, in 6 out of 8 cases the overlapping occurred when the victim was unknown and a prostitute.

When comparing sexualized with grievance femicides some significant differences emerged. Sexualized (90.9%; n = 60) in comparison with grievance (9.1%; n = 6) femicides more likely involved unknown victims (OR = 0.05; 95% CI = 0.01–0.16). When the victim and perpetrator knew each other, their relationship was characterized by a lower level of contentiousness in sexualized femicide (4.4%; n = 2) in comparison with grievance femicide (42.1%; n = 8) (OR = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.01–0.35). Prostitutes were more likely the victims of sexualized (88.1%; n = 59) than grievance femicides (42.9%; n = 9) (OR = 9.83; 95% CI = 3.16–30.65). Motives for sexualized femicides were mostly antisocial, characterized by sexual deviance, in comparison with grievance femicides in which the oppressive component of the relationship prevailed (OR = 9.30; 95% CI = 2.65–32.65).

No difference was found when compared the criminal careers of sexual and non-sexual femicidal offenders.

Comparing sexual femicides and rape

When looking in more detail at all the forms of violence analyzed in this study, some interesting results emerge.

What do sexual femicides have in common with rape?

Sexual femicides were more likely to be committed by an unknown man in an anonymous setting, in comparison with rape, in which the perpetrator knew the victim (OR = 0.17; 95% CI = 0.10–0.31). In sexual femicide, the relationship between the victim and perpetrator was less likely characterized by contentiousness than in cases of rape (OR = 0.41; 95% CI = 0.19–0.88). The victim and perpetrator were less likely to live together in cases of sexual femicide compared with rape (OR = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.02–0.20). The intensity of the relationship between victim and perpetrator (i.e., intimacy) was not significantly different in the cases of sexual femicides and rape. The duration of their relationship, jealousy and stalking were not significant in differentiating when comparing sexual femicides and rape.

Typically, sexual femicide tended to occur more likely in secluded spaces (OR = 0.24; 95% CI = 0.14–0.43) in comparison with rape, that occurred more likely in either the victim’s or the perpetrator’s home. Substance abuse by the perpetrator around the time of the violence was more likely in rape than in sexual femicide (OR = 0.17; 95% CI = 0.09–0.32).

The use of improper weapons was more likely in sexual femicide than rape (OR = 3.14; 95% CI = 1.55–6.37). Body exploitation (OR = 29.81; 95% CI = 11.11–79.94) and body mutilation (OR = 4.92; 95% CI = 1.70–14.20) were more likely to occur in sexual femicide than in rape (see Table 3 for a detailed overview of the results). No difference was found in the types of reaction of the perpetrator after the crime.

Comparing non-sexual femicides and rape

What do non-sexual femicides have in common with rape?

Knowing the perpetrator (OR = 2.41; 95% CI = 1.50–3.87), and being in a long relationship with him (OR = 2.13; 95% CI = 1.26–3.59) was more likely in non-sexual femicides rather than in rape (see note 3). When looking at the intensity of the relationship between victim and perpetrator (i.e., intimacy), no differences were found when comparing non-sexual femicides with rape. The risk for children witnessing the violence was strongly increased in those cases in which their mother was raped rather than killed (OR = 0.37; 95% CI = 0.20–0.67).

It was more likely that an oppressive relationship was behind the motives for non-sexual femicide rather than rape (OR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.30–0.69). Non-sexual femicides were more likely committed at home in comparison with rape (OR = 1.80; 95% CI = 1.14–2.83). As expected, substance use by the perpetrator was more frequent in rape than in non-sexual femicide (OR = 0.12; 95% CI = 0.08–0.20).

The exploitation of the victim’s body was almost four times more likely in the case of non-sexual femicide rather than in rape (OR = 3.67; 95% CI = 1.40–9.61), while an active reaction of the perpetrator after the violence was more frequent in rape rather than in non-sexual femicide (OR = 0.05; 95% CI = 0.02–0.11). No difference was found for body mutilation. All these findings are shown in Table 3.

Looking at these findings, and in line with previous studies (Krantz and Garcia-Moreno, 2005; Fernandez, 2011) it is noticeable that rape is part of a form of combined violence against women because it emerges either as a form of sexual violence within IPV or as the prevalent form of violence (rape ‘only’).

Looking for similarities and differences between sexual and non-sexual femicides and rape

These findings suggest that while sexual and non-sexual femicides share the killing of the victims, some aspects could make them more criminogenically closer to rape.

What do sexual femicides have in common with rape ‘only’ and rape within IPV?

As reported in Table 5, when comparing sexual femicide with either rape within IPV or rape ‘only’ some interesting findings emerged respectively. For instance, sexual femicides were more likely to differ from rape within IPV, because victims were more likely to be unknown while the victims of rape within IPV were more likely to be intimate, involved in an oppressive and contentious relationship with the perpetrator; often violence occurred in the presence of children and at home. Perpetrators of rape within IPV were more likely to have criminal records than for sexual femicide.

Table 5. Comparisons of sexual femicide and non-sexual femicide with rape within IPV and rape ‘only.’

Table 5 reports all results of this comparative analysis.

On the other hand, sexual femicide and rape ‘only’ involved mostly unknown victims. They were more likely to occur in public places and mainly for predatory and antisocial motives. In those cases of rape ‘only,’ it was more likely that the perpetrator was under the effect of alcohol or drugs. These offenders had also more previous criminal records in comparison with sexual femicidal offenders.

What do non-sexual femicides have in common with rape ‘only’ and rape within IPV?

Non-sexual femicides were similar to rape within IPV because both involved victims and perpetrators in a longer relationship, characterized by high level of contentiousness between them, and morbid jealousy. However, there were some differences when looking at the motives for violence which were more likely to be predatory and antisocial in non-sexual femicide than in rape within IPV. Perpetrators of rape within IPV were more likely to report previous criminal records. It was more likely that rape within IPV occurred at home and that abuse of substance was involved (see Table 5 for the details regarding these results).

Non-sexual femicides differently from rape ‘only’ involved known victims and were more likely to have occurred within an oppressive and multiproblematic relationship. Body exploitation was more likely in the cases of non-sexual femicide suggesting the use of some forms of torture during the violence.

It is interesting to note that perpetrators of non-sexual femicide were more likely to admit the crime in comparison with perpetrators of both rape within IPV and rape ‘only,’ who more likely either denied or escaped from the crime scene (see Table 5).

Discussion

This study examines cases of violence against women in northern Italy, focusing on sexual and non-sexual femicides and comparing them with rape (rape within IPV and rape ‘only’) (see Figure 1 for a summary of these forms of violence). Rape by itself or in combination with IPV or femicide, i.e., sexual femicide, means the violation of the most intimate dimension of a person: her own sexuality.

The results presented here, in line with other research findings (Campbell et al., 2003; Veggi et al., 2021), show that these types of violence against women reveal interesting similarities regarding types of victims, and the turbulent, oppressive, and domineering relationships with their perpetrators.

Sexual femicides exhibited a specific pattern in terms of victims (more likely to be unknown), of motives (more likely to be antisocial and sexually deviant), of characteristics of the crime dynamic (more likely to occur in secluded locations), and of perpetrators who were more likely to use improper weapons and to escape from the crime scene compared to non-sexual femicides. Sexual femicides also shared some similarities with rape, particularly regarding victim only known superficially or only involved in a short-term relationship with the perpetrator. Women who are victims of sexual femicide often experience a prolonged pattern of abuse and torture, are often left unclothed after being raped and mutilated. Whether or not they know their killer influences how and why they become the target of such extreme violence.

Sexual versus non-sexual femicides

Sexual femicide was seen in this study as an extreme form of control and domination in which sex was used to degrade the woman to the point of death. The manifestation of violence was characterized by a specific pattern. Victims of sexual femicide were indeed more likely to be unknown and to be killed in a remote public place, with an improper weapon. Results also show that victims who engaged in prostitution were at a higher risk than other women of being victim of sexual femicides. Prostitutes were more likely victims of a sexualized femicide.

As emerged in other international studies (Regoeczi and Miethe, 2003; Zara et al., 2021), knowing or not knowing the perpetrator could make a difference in the way the woman was killed. These findings are consistent with statements in the literature (Meloy, 2000) that sexual femicides tend to be characterized by further exploitation of the victim’s body and mutilation: an ultimate expression of control, deviant sexuality, and anger toward women are seen as the main incentives for this form of lethal violence.

However, most women in this study were killed by a man they knew, albeit with different levels of involvement with him and duration of the relationship (see Table 1 for a description of the variables involved). As shown in Table 3, the type of relationship between victim and perpetrator could impact on how violence was acted out and on its intensity. Known victims were more exposed to non-sexual femicide, which more likely took place at home, in the context of a domestic dispute, and in the presence of their children, as other studies suggest (see Matias et al., 2020). It was not unusual that in non-sexual femicide the perpetrator either confessed the killing or committed suicide soon after the femicide.

It is Geberth (2018) who suggested that a certain type of abusive personality, under certain situational settings, can escalate to the worst because “an enraged lover or spouse who is acting under extreme emotional circumstances is capable of anything” (p. 452 as cited in Stefańska et al., 2021, p. 16). In non-sexual femicides, the relationship between victim and perpetrator was more likely to be characterized by contentiousness, suggesting a prolonged involvement in an oppressive climate of emotional tension, where a destructive, strained and turbulent relationship between them was, often, the trigger to femicide. This is why this form of violence against women is considered preventable (Jung and Stewart, 2019): early intervention could prevent the lethal escalation of IPV to femicide.

Rape within IPV and rape ‘only’: A brief comparison with non-sexual and sexual femicides

In this research, rape emerged as part of a pattern of intimate partner violence (rape within IPV) or as a sexual crime (rape ‘only’). Known victims were more likely victims of intimate partner violence within which sexual violence clustered together abuse, control, domination, humiliation, making it a ‘composite’ form of violence (Table 5 summarizes these results).

Men strive for control, and rape, especially when occurred within IPV, can be one of the most disempowering experience for the woman. The more the woman is deprived of her choice and consent, the stronger the man’s control becomes. Victims of rape within IPV seem to share more characteristics with the victims of non-sexual femicide: the nature and duration of the relationship between victim and perpetrator could explain most of the similarities between these apparently different forms of violence against women (see Table 5 which summarizes these results).

As mentioned previously, and sustained by other studies, non-sexual femicide and rape within IPV are in line with the concept of proprietariness in which the woman is entitled to exist to the extent her partner allows her to do so (Gino et al., 2019; Spencer and Stith, 2020). This was evident in many cases of rape within IPV such as the one described below.

“A woman (38 years old) decided to leave her abusive and violent partner after countless episodes of physical, sexual, psychological, and economic violence in a relationship that lasted more than 10 years. For him, it was unacceptable that she tried to break up with him, and he demanded to get back the dentures he had paid for. The woman lost all her teeth in one of the abusive incidents she experienced in her relationship with him. She remained with him for many years after this incident.”

Sexual femicides tend to be an extreme form of using the woman as a sexual commodity.

Results show that in this study sexual femicides took different forms of sexualized and grievance, depending on the prevalent role of mostly sex or anger in the escalation into femicide, and on the relationship between perpetrator and victim.

The use, consume and dispose script is mostly featured in these types of sexual femicide because “what rape is to others is normal to prostitutes” (Farley et al., 2005, p. 254, italics added, as cited in Zara et al., 2021, p. 20). The fact that a significant proportion of victims of sexual femicides in this study were prostitutes is supported in the literature (e.g., Salfati, 2000; Salfati et al., 2008).

Victims were more likely to be unknown, to be abused and killed for antisocial and sexually deviant motives, and in secluded places. However, while in the case of sexual femicide it was more likely that improper weapons were used by the killer, in the cases of rape ‘only’ substance abuse by the perpetrator was a factor that enhanced the disinhibition by which the sexualized anger was manifested.

When looking at victims of rape, especially of rape ‘only,’ our findings suggest that they shared similar characteristics with victims of sexualized femicides who are more likely prostitutes. Similarities and differences are synthesized in Tables 3, 5.

Grievance and sexualized femicides

As shown in Table 4, victims of grievance femicides were more likely to know their perpetrators, and less likely to be prostitutes. What seems to have prevailed for these types of sexual femicidal offenders were angry cognitive schemas that might have promoted the excessively aggressive response in what might have been initially a consensual sexual situation (Stefańska et al., 2015). In other words, as suggested in the literature (Beech et al., 2005), grievance femicides were driven by the preoccupation and anxiety of losing contact with the woman (e.g., fear of being deserted), high emotionality, and angry rumination.

On the other hand, sexualized femicides involved more frequently unknown victims, although perpetrators may have targeted specific victims (e.g., prostitutes). Sexualized femicides were likely to be driven by predatory schema in which the victim was dehumanized and her body made the target of further exploiting actions. This is in line with clinical studies that suggest that victims of sexualized femicides are used as a sexual commodity to satisfy sexual, sadistic, and pervert urges (Meloy, 1997a). Such exploiting behavior was found to be more representative of sexual femicides than both non-sexual femicides and sexual violence.

Not dead enough: Body exploitation and mutilation

The presence of body exploitation and body mutilation of victims was examined and then compared with both sexual and non-sexual femicide, and also compared with rape. In line with other studies (Beech et al., 2005; Stefańska et al., 2015), these findings showed that the sexual factor in sexual femicides depended on whether the victims knew the perpetrators or not, and on the victims themselves. For instance, those victims whose body was exploited after their killing were more likely to be prostitutes. Prostitutes are over-exposed to the risk of workplace violence by their clients and tend to be killed more heinously than women who are not prostitutes, regardless of the degree of knowledge of the perpetrator (Marco Francia, 2021; Zara et al., 2021).

Stalking

Even though not directly explored, stalking occurred in only about 10% of the sample. It is possible that many stalking behaviors went undetected or not reported by the victims (Miller, 2012). Results show that stalking was more likely in cases of rape within IPV, suggesting that obsessive pursuit of intimacy is reinforced by a partner who is perceived as attainable the more the perpetrator attempts to control and dominate her. These preliminary findings are in line with international literature (Douglas and Dutton, 2001; Fox et al., 2011) that indicate that stalking and IPV share many similar dimensions because both crimes are characterized by unwanted, harassing, intrusive and frightening and/or intimidating behaviors.

Stalking has rarely been examined in studies of sexual and non-sexual femicide, and the extent of the association is not well understood (Campbell et al., 2007; Stefańska et al., 2021). Further specific research on stalking behavior in cases of femicide and rape deserves attention, as early identification of conditions that promote and reinforce the pursuit of intimacy may help prevent femicide and prevent the continuation of violence.

Limitations of the study

These findings are not without limitations. All femicide data were retrospective, and it was not possible to gather first-hand information from family members about the quality of the relationship between victim and perpetrator, and from perpetrators about the motives behind the killing. The evidence gathered explains only part of the dynamics of the intimate partner violence that fostered the femicide. Furthermore, it was impossible, with these data, to reconstruct with preciseness the victimogenic factors that interacted with other factors to escalate into sexual and non-sexual femicides, and that distinguished them from those victimogenic factors involved in rape.

Information on the victims were gathered through clinical and forensic reports so it was not possible to examine directly and in detail the conditions in which the victims were in before the crime (e.g., anxiety and preoccupation over their lives). Specific information about victims could be helpful for organizing preventive interventions.

We were unable to explore further the sexual nature of femicides because the information gathered were exclusively based on the forensic pathology reports, while access to the family members of the victims or to the offenders was not possible. Needless to say that getting in contact with the family members of the victims or perpetrators was beyond the scope of this study. Research findings (Beech et al., 2005; Stefańska et al., 2015) showed that deviant sexual and sadistic fantasies are an important factor in the characterization of sexual femicides. However, because analyses were based on the information presents in the files available, in this study it was not possible to assess the impact of deviant fantasies upon femicides.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to understanding similarities and differences in these forms of violence against women. Non-sexual femicides and rape within IPV have in common aspects related to known victims with whom the perpetrators had an intimate relationship. The relationship between victim and perpetrator can make a difference in how, where and for how long the abuse is endorsed before transforming itself into the physical death of the woman.

Sexual femicides and rape ‘only’ are likely to involve unknown victims. Sex was the common denominator of these types of violence against women.

Conclusion

While the ultimate goal of science and governments is to prevent all forms of violence against women, their intermediate goal should be to prevent violence from worsening to the point of killing. The fact that nearly a quarter of perpetrators had prior criminal records is an indication that violence against women in all its forms is a crime characterized by significant persistence over time, and it is possible that some violent incidents went unreported, contributing to the dark number that features in these different forms of violence against women. Governments should always rely on evidence-based research in order to make it possible for every woman to begin again in life, and not in death.

Given that ‘until death all is life,’ to paraphrase Paley (1999), every woman deserves the open destiny of life and should be assured that human rights are fully respected and endorsed because violence against women is a crime that victimizes all people, not just women.

Data availability statement

The dataset involves sensitive data (e.g., criminal records, forensic files) and only in particular circumstances could be made it available under the authorization of authorities. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to GZ, georgia.zara@unito.it.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by in order to meet all the ethical standards, the researchers followed all possible procedures to ensure confidentiality, fair treatment of data and information, and to guarantee, at each stage of the research, that the material was treated with respect and discretion. The research protocol was organized according to The Italian Data Protection Authority Act nr. 9/2016 (art. 1 and 2: application and scientific research purposes; art. 4: cases of impossibility to inform the participants, e.g., deceased people), to The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans (2013), and to the recent General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (2018). It was carried out in line with the Italian and the EU code of human research ethics and conduct in psychology, forensic pathology and legal medicine. Both research projects were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Turin (respectively for the femicide study with protocol nr. 191414/2018; for the sex offending project with protocol nr. 6494/2018). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GZ, SG, SV, and FF conceived, planned, and organized the study, drafted the article, and interpreted the results. GZ and SV attained and coded the data and critically revised the article. GZ designed the study and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.957327/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ For a more comprehensive view of statistics see also: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/rape-statistics-by-country.

- ^ Considering that the victims were exclusively women and the perpetrators exclusively men, we are confident that it is appropriate to speak of sexual and non-sexual femicides when referring to this study, even though Skott et al. (2018) used the general term “homicide.”

- ^ Data on femicide were collected at the Institute of Legal Medicine and at the Archive of the Morgue of Turin and they are part of a longitudinal research project on VaW (Zara and Gino, 2018). Data on rape are from the SORAT (Sex Offending Risk Assessment and Treatment) project (Zara, 2018). All data were anonymized and made unidentifiable; data were also numerically coded for statistical purposes.

- ^ According to Cohen (1992), values of effect size are interpreted as follows: 0.20 = small effect. 0.50 = medium effect. 0.80 = large effect.

- ^ On average the length of relationship between the victim and perpetrator was 6.02 years long (SD = 8.07) in the case of sexual femicide, and 15.06 years long (SD = 14.08) for non-sexual femicide, t(195) = 2.53, p = 0.01, (d = 0.66). On average the length of relationship between the victim and perpetrator was longer in the case of femicide, than for rape (M = 9.62; SD = 10.61), t(263) = 3.15, p = 0.001, (d = 0.42). The length of relationship between the victim and perpetrator was slightly shorter (M = 6.02; SD = 8.07) in the case of sexual femicide, than for rape, t(98) = −1.29, p = 0.01, (d = 0.35).

- ^ A graphical representation of the comparative results of sexual vs. non-sexual femicides vs. rape can be found in the Supplementary material (see Graph 1a, 1b, and 1c).

References

Adriaenssens, S., Geymonat, G. G., and Oso, L. (2016). Quality of work in prostitution and sex work. introduction to the special section. Soc. Res. 21, 121–132. doi: 10.5153/sro.4165

Bagwell-Gray, M. E., Messing, J. T., and Baldwin-White, A. (2015). Intimate partner sexual violence: A review of terms, definitions, and prevalence. Trauma Violence Abuse 16, 316–335. doi: 10.1177/1524838014557290

Beauregard, E., and Martineau, M. (2016). The sexual murderer: Offender behaviour and implications for practice. London: Routledge.

Beauregard, E., and Proulx, J. (2002). Profiles in the offending process of nonserial sexual murderers. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 46, 386–399. doi: 10.1177/0306624X02464002

Beauregard, E., DeLisi, M., and Hewitt, A. (2018). Sexual murderers: Sex offender, murderer, or both? Sex. Abuse 30, 932–950. doi: 10.1177/1079063217711446

Beech, A., Fisher, D., and Ward, T. (2005). Sexual Murderers’ Implicit Theories. J. Interpers. Violence 20, 1366–1389. doi: 10.1177/0886260505278712

Birkley, E. L., and Eckhardt, C. I. (2015). Anger, hostility, internalizing negative emotions, and intimate partner violence perpetration: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 37, 40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.002

Braulin, F. (2002). La questione sanitaria nella trieste di Fine 800: I caratteri antropologici della medicina ospedaliera sul litorale austriaco. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Burgess, A. W., Hartman, C. R., Ressler, R. K., Douglas, J. E., and McCormack, A. (1986). Sexual Homicide: A motivational model. J. Interpers. Violence 1, 251–272. doi: 10.1177/088626086001003001

Buss, D. M. (2000). The dangerous passion. Why jealousy is as necessary as love and sex. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Caman, S., Sturup, J., and Howner, K. (2022). Mental disorders and intimate partner femicide: Clinical characteristics in perpetrators of intimate partner femicide and male-to-male homicide. Front. Psychiatry 13:844807. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.844807

Campbell, J. C., Glass, N., Sharps, P. W., Laughon, K., and Bloom, T. (2007). Intimate partner homicide: Review and implications of research and policy. Trauma Violence Abuse 8, 246–269. doi: 10.1177/1524838007303505

Campbell, J. C., Webster, D., Koziol-McLain, J., Block, C., Campbell, D., Curry, M. A., et al. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. Am. J. Public Health 93, 1089–1097. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089

Carter, A. J., and Hollin, C. R. (2014). “Assessment and treatment when sex is attached to a killing: A case study,” in Sex offender treatment, eds D. T. Wilcox, T. Garett, and L. Harkins (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 286–304.

Carter, A. J., Hollin, C. R., Stefańska, E. B., Higgs, T., and Bloomfield, S. (2017). The use of crime scene and demographic information in the identification of nonserial sexual homicide. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 61, 1554–1569. doi: 10.1177/0306624X16630313

Chan, H. C. O. (2015). Understanding sexual homicide offenders: An integrated approach. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chan, H. C. O. (2017). “Sexual homicide: A review of recent empirical evidence (2008 to 2015),” in The handbook of homicide, eds F. Brookman, E. R. Maguire, and M. Maguire (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons), 105–130.

Cleere, C., and Lynn, S. J. (2013). Acknowledged versus unacknowledged sexual assault among college women. J. Interpers. Violence 28, 2593–2611. doi: 10.1177/0886260513479033

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20, 37–47. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., McKeown, R. E., and King, M. J. (2000). Frequency and Correlates of Intimate Partner Violence by Type: Physical, Sexual, and Psychological Battering. Am. J. Public Health 90, 553–559. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.4.553

Davies, L., Ford-Gilboe, M., Willson, A., Varcoe, C., Wuest, J., Campbell, J., et al. (2015). Patterns of cumulative abuse among female survivors of intimate partner violence: Links to women’s health and socioeconomic status. Violence Against Women 21, 30–48. doi: 10.1177/1077801214564076

Dawson, M., and Gartner, R. (1998). Differences in the characteristics of intimate femicides. the role of relationship state and relationship status. Homicide Stud. 2, 378–399. doi: 10.1177/1088767998002004003

Di Nunno, N., Costantinides, F., Vacca, M., and Di Nunno, C. (2006). Dismemberment: A review of the literature and description of 3 cases. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 27, 307–312. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000188170.55342.69

Dorland, W. A. N. (2012). Dorland’s illustrated medical dictionary, 32nd Edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.

Douglas, K. S., and Dutton, D. G. (2001). Assessing the link between stalking and domestic violence. Aggress. Violent Behav. 6, 519–546. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00018-5

Dylewski, Ł, and Prokop, P. (2021). “Prostitution,” in Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science, eds T. K. Shackelford and V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Cham: Springer), 6331–6334. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_270

Farley, M., Lynne, J., and Cotton, A. (2005). Prostitution in vancouver: Violence and the colonization of first nations women. Trans. Psychiatry 42, 242–271. doi: 10.1177/1363461505052667

Farrington, D. P., and Loeber, R. (2000). Some benefits of dichotomization in psychiatric and criminological research. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 10, 100–122. doi: 10.1002/cbm.349

Fazel, S., Sjostedt, G., Langstrom, N., and Grann, M. (2007). Severe mental illness and risk of sexual offending in men: A case–control study based on Swedish national registers. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 588–596. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0415

Fernandez, P. A. (2011). Sexual assault: An overview and implications for counselling support. Med. J. Aust. 4, 596–602. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2011858

Feshbach, S. (1964). The function of aggression and the regulation of aggressive drive. Psychol. Rev. 71, 257–272. doi: 10.1037/h0043041

Flynn, A., and Graham, K. (2010). Why did it happen?” A review and conceptual framework for research on perpetrators’ and victims’ explanations for intimate partner violence. Aggress. Violent Behav. 15, 239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2010.01.002

Fox, K. A., Nobles, M. R., and Akers, R. L. (2011). Is stalking a learned phenomenon? An empirical test of social learning theory. J. Crim. Justice 39, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.10.002

Freilone, F., Roscioli, A., and Zara, G. (2020). Gelosia Omicida: Analisi criminologica di un caso. Psichiatria Psicoterapia 39, 111–121.

Geberth, V. J. (2016). Practical homicide investigation. Tactics, procedures, and forensic techniques. Boca Raton, FL: Tylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Geberth, V. J. (2018). “Sex-related homicide investigations,” in Routledge international handbook of sexual homicide studies, eds J. Proulx, A. J. Carter, E. ì Beauregard, A. Mokros, R. Darjee, and J. James (Abingdon: Routledge), 448–470.

Gellerman, D. M., and Suddath, R. (2005). Violent fantasy, dangerousness, and the duty to warn and protect. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 33, 484–495.

Gino, S., Freilone, F., Biondi, E., Ceccarelli, D., Veggi, S., and Zara, G. (2019). Dall’Intimate partner violence al femminicidio: Relazioni che uccidono (From IPV to femicide: Relationships that kill). Rass. Ital. Criminol. 10, 129–146. doi: 10.7347/RIC-022019-p129

Guggenheimer, D., Caman, S., Sturup, J., Thiblin, I., and Zilg, B. (2021). Criminal mutilation in Sweden from 1991 to 2017. J. Forensic Sci. 66, 1788–1796. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.14736

Häkkänen-Nyholm, H., Repo-Tiihonen, E., Lindberg, N., Salenius, S., and Weizmann-Henelius, G. (2009). Finnish sexual homicides: Offence and offender characteristics. Forensic Sci. Int. 188, 125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.03.030

Harned, M. S. (2005). Understanding women’s labeling of unwanted sexual experiences with dating partners: A qualitative analysis. Violence Against Women 11, 374–413. doi: 10.1177/1077801204272240

Heron, R. L., Eisma, M. C., and Browne, K. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of disclosing domestic violence to the UK Health Service. J. Fam. Viol. 37, 533–543. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00236-3

Higgs, T., Carter, A. J., Tully, R. J., and Browne, K. D. (2017). Sexual murder typologies: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 35, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2017.05.004

Holmes, R. M., and Holmes, S. (2001). Mass murder in the United States. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Holtzworth-Munroe, A., and Stuart, G. L. (1994). Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychol. Bull. 116, 476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476

Horley, J., and Clarke, J. (2016). Experience, meaning, and identity in sexuality. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Johnson, H., Eriksson, L., Mazerolle, P., and Wortley, R. (2017). Intimate Femicide: The role of coercive control. Fem. Criminol. 14, 3–23. doi: 10.1177/1557085117701574

Johnson, M. P. (2008). A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Jordan, C. E., Pritchard, A. J., Duckett, D., Wilcox, P., Corey, T., and Combest, M. (2010). Relationship and injury trends in the homicide of women across the lifespan: A research note. Homicide Stud. 14, 181–192. doi: 10.1177/1088767910362328

Jung, S., and Stewart, J. (2019). Exploratory comparison between fatal and non-fatal cases of intimate partner violence. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 11, 158–168. doi: 10.1108/JACPR-11-2018-0394

Kahn, A. S., Jackson, J., Kully, C., Badger, K., and Halvorsen, J. (2003). Calling it rape: Differences in experiences of women who do or do not label their sexual assault as rape. Psychol. Women Q. 27, 233–242. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00103

Karakasi, M. V., Vasilikos, E., Voultsos, P., Vlachaki, A., and Pavlidis, P. (2017). Sexual homicide: Brief review of the literature and case report involving rape, genital mutilation and human arson. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 46, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2016.12.005

Karger, B., Rand, S. P., and Brinkmann, B. (2000). Criminal anticipation of DNA investigations resulting in mutilation of a corpse. Int. J. Legal Med. 113, 247–248. doi: 10.1007/s004149900092

Kelley, S. M., Thornton, D., Mattek, R., Johnson, L., and Ambroziak, G. (2020). Exploring the relationship between major mental illness and sex offending behavior in a high-risk population. Crim. Justice Behav. 47, 290–309. doi: 10.1177/0093854819887204

Konopka, T., Strona, M., Bolechała, F., and Kunz, J. (2007). Corpse dismemberment in the material collected by the department of forensic medicine. Cracow Poland. Leg. Med. 9, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2006.08.008

Krantz, G., and Garcia-Moreno, C. (2005). Violence against women. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 59, 818–821. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.022756

Langevin, R., Ben-Aron, M., Wright, P., Marchese, V., and Handy, L. (1988). The sex killer. Ann. Sex Res. 1, 263–301. doi: 10.1177/107906328800100206

Littleton, H. L., Layh, M., and Rudolph, K. (2018). Unacknowledged rape in the community: Rape characteristics and adjustment. Violence Vict. 33, 142–156. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-16-00104

Littleton, H. L., Rhatigan, D., and Axsom, D. (2007). Unacknowledged rape: How much do we know about the hidden rape victim? J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 14, 57–74. doi: 10.1300/J146v14n04_04

Marco Francia, M. P. (2021). “Mujer, prostitución y violencia de género,” in Estudios sobre mujeres y feminismo: Aspectos jurídicos, políticos, filosóficos e históricos, ed. M. C. Escribano Gámir (Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha), 49–62.

Marks, J., Markwell, A., Randell, T., and Hughes, J. (2020). Domestic and family violence, non-lethal strangulation and social work intervention in the emergency department. Emerg. Med. Australas. 32, 676-678. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13519

Masters, N. T., Casey, E., Wells, E. A., and Morrison, D. M. (2013). Sexual scripts among young heterosexually active men and women: Continuity and change. J. Sex Res. 50, 409–420. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.661102

Matias, A., Gonçalves, M., Soeiro, C., and Matos, M. (2020). Intimate partner homicide: A meta-analysis of risk factors. Aggress. Violent Behav. 50, 1359–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2019.101358

McGuire, M., and Gruter, M. (2003). “Prostitution – An Evolutionary Perspective,” in Human nature and public policy: An evolutionary Approach, eds A. Somit and S. A. Peterson (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 29–40. doi: 10.1057/9781403982094_3

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 22, 276–282. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031

Meloy, J. R. (1997a). Predatory violence during mass murder. J. Forensic Sci. 42, 326–329. doi: 10.1520/JFS14122J

Meloy, J. R. (1997b). “A clinical investigation of the obsessional follower: “she loves me, she loves me not,” in Explorations in criminal psychopathology, ed. L. Schlesinger (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas), 9–32.

Meloy, J. R. (2000). The nature and dynamics of sexual homicide: An integrative review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 5, 1–22. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(99)00006-3

Merlone, U., Manassero, E., and Zara, G. (2016). “The lingering effects of past crimes over future criminal careers,” in Proceedings of the 2016 Winter Simulation Conference. December 11-14 2016, eds T. M. K. Roeder, P. I. Frazier, R. Szechtman, E. Zhou, T. Huschka, and S. E. Chick (Washington, DC: 2016 Winter Simulation Conference), 3532–3543.

Miller, L. (2012). Stalking: Patterns, motives, and intervention strategies. Aggress. Violent Behav. 17, 495–506. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.07.001

Myers, W. C., Burgess, A. W., Burgess, A. G., and Douglas, J. E. (1999). “Serial murder and sexual homicide,” in Handbook of psychological approaches with violent offender, eds V. B. Van Hasselt and M. Hersen (Berlin: Springer), 153–172.

Neppl, T. K., Lohman, B. J., Senia, J. M., Kavanaugh, S. A., and Cui, M. (2019). Intergenerational continuity of psychological violence: Intimate partner relationships and harsh parenting. Psychol. Violence 9, 298–307. doi: 10.1037/vio0000129

Oram, S., Flynn, S. M., Shaw, J., Appleby, L., and Howard, L. M. (2013). Mental illness and domestic homicide: A population-based descriptive study. Psychiatr. Serv. 64, 1006–1011. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200484

Pelletier, K. R., and Pizarro, J. M. (2019). Homicides and weapons: Examining the covariates of weapon choice. Homicide Stud. 23, 41–63. doi: 10.1177/1088767918807252

Peterson, Z. D., and Muehlenhard, C. L. (2011). A match-and-motivation model of how women label their nonconsensual sexual experiences. Psychol. Women Q. 35, 558–570. doi: 10.1177/0361684311410210

Petersson, J., Strand, S., and Selenius, H. (2019). Risk factors for intimate partner violence: A comparison of antisocial and family-only perpetrators. J. Interpers. Violence 34, 219–239. doi: 10.1177/0886260516640547

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., and Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Regoeczi, W. C., and Miethe, T. D. (2003). Taking on the unknown: A qualitative comparative analysis of unknown relationship homicides. Homicide Stud. 7, 211–234. doi: 10.1177/1088767903253606

Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., and Douglas, J. E. (1988). Sexual homicide: Patterns and motives. Lexington, KY: Lexington Books.

Russell, D. E. H., and Harmes, R. (2001). Femicide in global perspective. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Salfati, C. G. (2000). The nature of expressiveness and instrumentality in homicide: Implications for offender profiling. Homicide Stud. 4, 265–293. doi: 10.1177/1088767900004003004

Salfati, C. G. (2003). Offender interaction with victims in homicide: A multidimensional analysis of frequencies in crime scene behaviors. J. Interpers. Violence 18, 490–512. doi: 10.1177/0886260503251069

Salfati, C. G., and Canter, D. (1999). Differentiating stranger murders: Profiling offender characteristics from behavioral styles. Behav. Sci. Law 17, 391–406. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0798(199907/09)17:3<391::AID-BSL352<3.0.CO;2-Z

Salfati, C. G., and Taylor, P. (2017). Differentiating sexual violence: A comparison of sexual homicide and rape. Psychol. Crime Law 12, 107–125. doi: 10.1080/10683160500036871

Salfati, C. G., James, A. R., and Ferguson, L. (2008). Prostitute homicides. A descriptive study. J. Interpers. Violence 23, 505–543. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312946

Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., Meyer, S. R., and García-Moreno, C. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet 399, 803–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7

Serran, G., and Firestone, P. (2004). Intimate partner homicide: A review of the male proprietariness and the self-defense theories. Aggress. Violent Behav. 9, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(02)00107-6

Skott, S., Beauregard, E., and Darjee, R. (2018). Sexual and Nonsexual Homicide in Scotland: Is There a Difference? J. Interpers. Violence 36, 3209–3230. doi: 10.1177/0886260518774303

Sorochinski, M., and Salfati, C. G. (2019). Sex worker homicide series: Profiling the crime scene. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 63, 1776–1793. doi: 10.1177/0306624x19839274

Sorrentino, A., Guida, C., Cinquegrana, V., and Baldry, A. C. (2020). Femicide fatal risk factors: A last decade comparison between Italian victims of femicide by age groups. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:7953. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217953