Abstract

The aims of this paper are to: (1) identify the best framework for comprehending multidimensional impact of deep brain stimulation (DBS) on the self; (2) identify weaknesses of this framework; (3) propose refinements to it; (4) in pursuing (3), show why and how this framework should be extended with additional moral aspects and demonstrate their interrelations; (5) define how moral aspects relate to the framework; (6) show the potential consequences of including moral aspects on evaluating DBS’s impact on patients’ selves. Regarding (1), I argue that the pattern theory of self (PTS) can be regarded as such a framework. In realizing (2) and (3), I indicate that most relevant issues concerning PTS that require resolutions are ontological issues, including the persistence question, the “specificity problem”, and finding lacking relevant aspects of the self. In realizing (4), I identify aspects of the self not included in PTS which are desperately needed to investigate the full range of potentially relevant DBS-induced changes—authenticity, autonomy, and responsibility, and conclude that how we define authenticity will have implications for our concept of autonomy, which in turn will determine how we think about responsibility. Concerning (5), I discuss a complex relation between moral aspects and PTS—on one hand, they serve as the lens through which a particular self-pattern can be evaluated; on the other, they are, themselves, products of dynamical interactions of various self-aspects. Finally, I discuss (6), demonstrating novel way of understanding the effects of DBS on patients’ selves.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

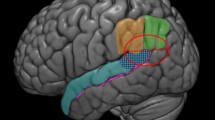

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an invasive treatment involving the implantation of electrodes and electrical stimulation of specific areas of the brain (Hemm & Wårdell, 2010; Herrington et al., 2016). Despite DBS’s therapeutic potential (see e.g., Fitzgerald & Segrave, 2015), it constitutes threats that have historically been only rarely discussed in neuroethics. Recently, however, many neuroethicists have expressed concerns over the potential danger to patients’ selves posed by DBS.Footnote 1 These concerns were initially raised by individual case reportsFootnote 2; however, various qualitative studies,Footnote 3 as well as a recent semiquantitative study (Eich et al., 2019) have proved their relevance.Footnote 4 These results have stimulated ongoing neuroethical debate concerning DBS’s impact on the self. However, how neuroethicists capture DBS-induced changes on patients’ selves depends on the conceptual scheme applied.Footnote 5 In this paper, I argue that the pattern theory of self (PTS) may be a candidate for understanding a broader range of consequences of DBS for patients’ selves than other proposed models of the self (section 2—Models of the self and their problems). However, there are still some difficult issues around PTS which must be resolved (discussed in the second part of section 2). Crucially, as I argue in section 3, there is a need to include moral aspects of the self. In sections 4 and 5, I show why the most relevant are authenticity, autonomy, and responsibility, and discuss how they relate to each otherFootnote 6; more precisely, I demonstrate that the concepts of authenticity, autonomy and responsibility are not independent, and thus they should not be considered in isolation, which is currently too often presumed practice in neuroethics. Instead, we should bear in mind that “[h]ow we define self and autonomy, then, will have some implications for how we think about responsibility” (Gallagher, 2018). I would add to this passage a further remark—the concept of authenticity which we assume in our considerations also will have an important role to play in this context. Thus, how we define the self will have implications for how we think about authenticity, and how we define authenticity will have implications for how we think about autonomy, and consequently, for how we think about responsibility.Footnote 7 Finally, in section 6, I discuss how moral aspects relate to PTS and what the potential consequences of their inclusion in PTS may be on evaluations of the effects of DBS on patients’ selves. I conclude (section 7—Summary) by pointing out more general theoretical gains from the inclusion of moral aspects within the PTS framework.

2 Models of the self and their problems

Analysing various accounts of this elusive yet familiar phenomenon, Dings and de Bruin (2016) claim that there is profound disagreement regarding a concept that adequately characterises the self in the context of the theoretical debate on the neuroethics of DBS. Furthermore, they argue that most approaches postulate relatively narrow concepts of the self, focusing on one or two of its aspects: the representational (Synofzik & Schlaepfer, 2008), cognitive (Witt et al., 2013), narrative (Schechtman, 2010), relational (Baylis, 2013), or enactive (de Haan et al., 2013) dimensions. Although they note that these limitations do not necessarily pose a problem for accounting for the effects of DBS in an individual patient, the fact that most proposed models aim to provide a complete explanation of DBS’s consequences for the self is problematic. This is because analysing them through the lens of only one of these models would omit relevant DBS-induced changes. Dings and de Bruin further criticise theories proposed up to this point by indicating that they are either based on the specific disorder, or discuss the effects of DBS in general; however, it may be that DBS’s effects on the self differ in patients with distinct disorders, and thus a fine-grained theory of the self should make a room for disorder-specificity in considering DBS’s impact. Joining this discussion, I also think that such a theory should allow us to consider emerging threats associated with DBS systems of a new generation, so-called “closed loop” DBS—closed-loop advisory brain devices (Gilbert et al., 2018a and b), or volitional closed-loop DBS (Goering et al., 2017), as they may considerably differ from the dangers posed by the most commonly utilised “open loop” DBS systems (see e.g., Brown, Moore, et al., 2016a).

Theoretical pluralism, a lack of consensus regarding an adequate concept of the self, the limitations of the proposed models, as well as a lack of room for disorder-specificity and DBS system-specificity are problematic in the context of the neuroethical debate, as these circumstances preclude the development of a consensual and adequate procedure for evaluating the implications of DBS for patients’ selves. This, in turn, does not allow proper calculation of the benefits and risks of decisions to initiate, continue, or discontinue DBS treatment, as well as other types of ethical decisions and recommendations.

To overcome these issues, Dings and de Bruin propose that neuroethical analysis should make use of the “pattern theory of self” (PTS) based on the work of Gallagher (2013). According to PTS the self should be considered as a cluster concept which includes certain characteristic aspects,Footnote 8 such as:

-

1.

embodied aspects, i.e., aspects that allow a biological system to distinguish between itself and what is not itself—these are core biological, ecological factors;

-

2.

minimal experiential aspects, i.e., first-person, pre-reflective, conscious experience—these reflect the self/non–self distinction, manifest in various sensory–motor modalities (touch, vision, proprioception, kinesthesia, hearing, etc.) and contribute to an experiential and embodied sense of ownership or mineness and a sense of agency;

-

3.

affective aspects, ranging from very basic and mostly covert or tacit bodily affects to typical emotional patterns or moods;

-

4.

behavioral aspects, i.e., behavioral habits that constitute our character;

-

5.

intersubjective aspects, i.e., ability to attune to intersubjective existence, for example, aspects that contribute to capacities such as gaze following and joint attention, which develops into a social self–consciousness—a self-for-others;

-

6.

psychological/cognitive aspects, ranging from explicit self-consciousness and memory, to conceptual understanding of self as self, and other reflective capacities, such as the ability to form second-order volitions about one’s desires (Frankfurt, 1971; Gallagher, 2018), to personality traits of which one may not be self-conscious at all;

-

7.

narrative aspects, i.e., aspects that contribute to the narrative structure of our self-interpretations;

-

8.

extended aspects, which may include physical pieces of property, the things we identify ourselves with, professions or institutions we work in as well as actions that they afford;

-

9.

normative aspects, ranging across possibilities presented by the kind of environment in which we grew up to cultural and normative practices involving gender, race, and economic status that define our way of living.

Dings and de Bruin point out that thanks to this multidimensionality, PTS allows to understand various conceptualizations of the self not as oppositions, but rather as potentially compatible or commensurable. As such, they argue, PTS is a particularly good candidate for capturing the full range of DBS-induced effects on the self.

In their own model, Dings and de Bruin modify the meta-theoreticalFootnote 9 framework of Gallagher by articulating it as a theory that can be applied to an individual DBS patient. In order to do so, they introduce two levels of analysis: of a particular pattern type and of an individual token. They conceptualise type-level as an inventory of “disordered selves”, i.e., the complete list of the dysfunctional and disruptive aspects and patterns of aspects indicative of a disease. They emphasise that the DSM-V can be used to identify what these disruptive patterns are in a particular disorder, e.g., the presence of obsessions, compulsions, or both in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) may affect embodied, experiential, cognitive/psychological, affective, and extended, as well as narrative aspects. When it comes to individuating the pattern of aspects constitutive of an individual self, Dings and de Bruin propose to situate these aspects by showing how contextual factors influence them. They emphasise Gallagher’s claim that the self emerge from the dynamic interactions of its constituent aspects, and that these interactions can take different values and weights in the particular individual’s constitution of the self. However, they add to this that “[s]elves emerge as the result of a dynamic interaction between their constituent aspects and the environment.” For example, in an academic context a person will most likely develop the cognitive rather than some other aspects of the self; in private life, however, affective aspects may be more emphasised. Dings and de Bruin point out that the continuity of the self can be understood in their model as a compound of second-order pattern and first-order patterns (or ‘sub-selves’). In the example above, this would mean that the second-order patterns consist of ‘academic’ and ‘private’ sub-selves; in turn, depending on the context, these first-order patterns can think/act/feel differently. This dynamic accounts for self-continuity of the particular individual.

The theoretical benefit of PTS intended by Dings and de Bruin is to enable us to take into account all relevant effects of DBS on the self, instead of constraining us to consider only one aspect at a time, e.g., the narrative aspect, as “deflationary” conceptions of the self do (Gallagher, 2018). Development of a model of the self that embraces all important aspects of the self is a pressing challenge, one that must be addressed in order to prepare a conceptual scheme enabling us to properly interpret clinical cases, and to allow us to solve neuroethical dilemmas. However, there are several questions that must to be answered before PTS could be accepted as such a framework. Firstly, as Dings, de Bruin, and Gallagher acknowledged themselves, there are ontological issues concerning their theoretical framework: PTS presupposes various aspects of the self, but what is the ontological status of an aspect? Furthermore, Dings and de Bruin claim that aspects of the self interact with each other and the environment. However, as de Haan et al.Footnote 10 (2017) state in their critique of PTS: “It is just a list; a heaping of aspects, without an account of how they relate. There are no considerations on their potential ordering, hierarchy or structure”. So, what precisely is this interrelation? Is it hierarchical? Do these aspects causally interact? Are these aspects functionally dependent—that is, in order to narrative aspect emerge, one has to already have more basic ones, e.g., embodied aspects? These questions are beginning to be addressed (see e.g., Dings, 2019; Gallagher & Daly, 2018; Kyselo, 2014). However, as Gallagher (2018) claims, “it is only through empirical and phenomenological studies that we will be able to sort out how the dynamics of the self-pattern change […]”. Therefore, it seems that we will have to wait to find answers for these questions until an empirical paradigm is developed.

What is a more urgent and relevant ontological issue from the perspective of neuroethical endeavours related to PTS, however, is the question about the relation of patterns constituting one’s self across time, which enable the preservation of personal identity. Dings and de Bruin (2016) briefly point out in the footnotes of their paper that, in principle, we may be able to explain the continuity of self in terms of a second-order pattern consisting of at least two different levels of patterns of the self (or subselves); patterns that, as discussed above, are expressed differently depending on the context (e.g., an “academic” and “private” subselves). However, their account does not answer for the crucial question of what aspects of the self must survive DBS-induced changes in order to preserve personal identity. Is it the intersection of aspects of various subselves? Which of these subselves are relevant for preserving personal identity? How many subselves are there? Moreover, it seems that de Bruin et al. (2017) further complicate this matter by stating: “Although PTS individuates selves as patterns of characteristic aspects, none of these aspects is necessary or sufficient for the existence of a particular self”; if one accepts this passage, it follows that one could never answer the question of persistence—that is, what does it take for a person (or the self) to persist from one time to another (Olson, 2019). Although one could argue that this conclusion is not particularly problematic, as the whole point of PTS is to undermine the very idea that the self has a “thing-like” persistence through time,Footnote 11 it seems that such a metaphysical position could be problematic for several reasons.

Following Quine’s classic slogan “no entity without identity”, one could argue that we should not postulate entities without having clear identity criteria for them, as the notion of identity brings clarity and definiteness to theory (Quine, 1969, 23). One does not have to feel entirely obliged to this passage, however, to see that any proposed model without identity criteria will lack the theoretical rigor so necessary in neuroethical assessments concerning the consequence of DBS treatment for the self. In narrative models of the self we have simple, although debatable, criteria for preserving personal identity: if a person cannot construct a narrative fulfilling articulatory and reality constraints (see Schechtman, 1996, 119–128), or given thoughts or actions are recognised as resulting from DBS’s action—not from the individual’s dispositions, plans, or desires that are part of the autobiographical narrative of the self—then personal identity is threatened (Schechtman, 2010). In PTS, different aspects contribute to one’s everyday experience of the self, although none of them, taken individually, is postulated to be necessary nor sufficient for preserving identity; for this reason, PTS fails in informing us whether DBS could endanger patients’ personal identity. Taking into account the moral relevance of personal identity—which plays an important role both in our ethical and legal considerations—it appears that this aspect of PTS should be refined.

3 The need to include moral aspects of the self

The aim of this article, however, is not to resolve the complicated ontological issues discussed above, but rather to contribute to PTS by identifying and examining aspects of the self, which are not included in PTS’s list, but surely deserve their own place on it. This is crucial for the success of the project of PTS as it aims to: “investigate the full range of potentially relevant DBS-induced changes” (Dings & de Bruin, 2016). This endeavour seems necessary because the list proposed in PTS lacks some important aspects of the self, as Dings and de Bruin themselves acknowledged. Considering this issue, the authors note that, depending on the person or the disease being investigated, one could include “spiritual or religious aspects”, or “moral aspects”. In further discussion of this point, they indicate that moral aspects should contain a special place for autonomy. I am sympathetic to this proposition; however, the extensive literature review undertaken in this paper reflects that as neuroethical discussion progresses, neuroethicists have engaged in consideration of the effects of DBS on patients’ selves by employing more relevant aspects of the self that PTS is silent upon. So, along with autonomy,Footnote 12 these include authenticityFootnote 13 and moral responsibility.Footnote 14 The engagement of researchers and constantly growing number of works that analyse the consequences of DBS on these aspects demonstrates that they are crucial in understanding DBS-induced threats to the patients’ selves, and, as such, these moral aspects should be included in PTS’s list. Below, I demonstrate why including them within PTS is necessary; to this end, I analyse DBS-induced changes in these moral aspects of the self.

Before that, however, it is worth noting here one methodological obstacle in this endeavour. We should have in mind that it is not self-evident when the authenticity, autonomy, or responsibility of the particular patient has been affected by DBS; it depends on the particular theory of authenticity, autonomy and responsibility adopted to interpret DBS-induced changes. For this reason, I am not attempting to find an “objective stance” in considering how DBS affects patients’ selves, but rather to analyse these effects through the lens of the most influential approaches of authenticity, autonomy and responsibility proposed in the neuroethical literature. Finally, I also wish to emphasize, regarding another important endeavour in this paper (to argue that authenticity, autonomy and responsibility are strictly interrelated) that this aim is crucial in the light of the claim of PTS that the self emerges from the dynamic interactions of its constituent aspects. For this reason, showing that similar relations between moral aspects take place also strengthens the argument to include each within the PTS framework—especially since, as I will argue in section 6, they are all dynamically interrelated with each of the other self-aspects postulated in PTS.

4 Autonomy, authenticity, and their interrelations

It seems natural that we should start this project by considering the notion pointed out as required for PTS by the authors of the theory themselves—autonomy. Christman (2018) claims that autonomy “[…] is simply a construction of a concept aimed at capturing the general sense of ‘self-rule’ […]. […] The idea of self-rule contains two components: the independence of one’s deliberation and choice from manipulation by others, and the capacity to rule oneself.” It seems that, for example, in a case of a patient known as “the Dutch Patient” (DP) (Leentjens et al., 2004), who experienced DBS-induced effects on the self, the decisions of medical stuff were in line with this general understanding of autonomy. DP was treated for Parkinson’s disease (PD) with the help of DBS. The treatment was effective in diminishing symptoms of the disease, but caused various side effects, including mania, megalomania, and impulsiveness. As the therapy appeared to be leading the patient to compulsive gambling, falling into debt, conflict with the police, and, ultimately, forced hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital, medical stuff faced a dilemma about whether the treatment should be terminated. The solution they implemented was to temporarily disable the device and then ask the patient about his will regarding the future of the therapy. They took this course of action because with the switched-on mode of the device, DP had not been believed to be mentally competent, that is, accountable and rational, and as such, had been unable to give informed consent. In the language of self-ruling, DP was considered to lack the capacity to deliberate, choose and rule himself independently of DBS’s impact; thus, DBS was regarded as a nonrational influence on DP’s reasoning, one that was undermining his authority to determine his own actions and rendering him non-autonomous. With his DBS switched off, DP decided that it is more important for him to stop the symptoms of PD than those caused by DBS, despite the fact he had to sign an advance directive agreeing to remain under psychiatric care for the rest of his life for the device to be reactivated.

In contrast to Glannon (2009), who interprets DP’s case in terms of a choice on “quality of life grounds”, that is, DP sacrificed his mental competence for his well-being (for a similar conclusion see Pugh et al., 2018), Kraemer (2013a) claims that an equally likely interpretation of this case is that DP faced a different kind of dilemma: “he had to choose between being autonomous, that is, mentally competent in the switched-off mode, and feeling authentic, albeit being manic, in the switched-on mode”. Kraemer guides her interpretation using other case studies she considers analogous to the case of DP in important regards. Relating to the case presented by Munhoz et al. (2009), Kraemer deliberates about whether DP could had said or thought something similar to the following: “[t]he person that drives his car too fast, that leads a promiscuous life and that runs into debts is really me! In my previous life, before stimulation, I did not dare to do such unreasonable things. I lived a well-adapted life—a life which I now see was never really mine. But now, I have the chance to be who I really am”. She claims that if we assume that such a narrative may be indeed attributed to DP’s situation, the possibility of a new interpretation of his dilemma arises. As she sees it, “[i]n the authentic state, he is no longer able to make any mentally competent, autonomous decisions in the future, and vice versa, when being mentally competent, he does not feel authentic”. Consequently, Kraemer reconceptualises DP’s dilemma as a dilemma between autonomy and authenticity.

Contrary to what Kraemer claims, however, the dilemma above can be seen as wrong-headed, as many of the influential contemporary accounts of autonomy instead view authenticity as a prerequisite for autonomy, and as such, hold these two concepts as not excluding, but rather fundamentally depending on each other (Wardrope, 2014). As Christman (2018) states, “[p]ut most simply, to be autonomous is to be one’s own person, to be directed by considerations, desires, conditions, and characteristics that are not simply imposed externally upon one, but are part of what can somehow be considered one’s authentic self”. So, where does Kraemer’s dilemma come from in the first place, and why does it not seem prima facie misplaced? It stems from an influential family of conceptions of autonomy, in which autonomy is identified with a set of competences, such as the capacity to choose deliberately and rationally. This model is often applied in medical ethics, as it allows “objective” assessment of whether a person is an autonomous agent, and thus if she has the ability to give informed consent (Berofsky, 1995; Dubljević, 2013; Haworth, 1986; Kraemer, 2013a). However, it seems that a theory of autonomy fully dependent upon rational assessment may be viewed as postulating an “inhuman” model of an autonomous person, by painting her as a cold, detached calculator (see Meyers, 2004, 111–137). For this reason, influential theoreticians, such as Friedman (2003), Meyers (2004), Wolf (1990), or Watson (1975), postulate that to rule oneself—that is, to be an autonomous person—one must be in a position to fulfil a condition postulated by the second among the influential families of conceptions of autonomy, authenticity.

Such a complementary approach is also in line with one of the most influential approaches to autonomy in recent decades, namely, hierarchical accounts of autonomy (see e.g., Dworkin 1976, 1988; Frankfurt, 1969, 1971), as they possess a built-in reference to authenticity. A seminal theory in this paradigm was proposed by Frankfurt, who argues that autonomy requires that a person possess second-order volitions which enables her to distance from, or identify with, a spontaneous, often elusive, first-order desires. Hierarchical accounts are on the opposite end of the spectrum from competence approaches as, according to the former, a necessary condition for being autonomous—a person’s higher-order attitudes—need not be especially rational or well-informed. In this view, autonomy simply emerges when a person identifies her higher-order volitions with first-order desires; this does not require that the content of these attitudes be rational. However, why are hierarchical accounts categorised as a family of conceptions referring to the concept of authenticity? For example, in Frankturt’s approach the reference and the relevance of authenticity in these theories lies in the postulate that in order for the action of a person to be regarded as autonomous, identification between different orders of attitudes must be “wholehearted”. Frankfurt (1988, 175) understands the wholeheartedness of identification to be an endorsement of “certain elements which are then authoritative for the self”. In the language of authenticity,Footnote 15 according to Frankfurt’s wholeheartedness account, an element of the self is authentic if endorsed wholeheartedly (Pugh et al., 2017b). Thus, according to Frankfurt’s approach, a person is not autonomous if she does not identify with her first-order desires, though she still behaves in accordance with what they dictate, or if the identification between attitudes is not a “decisive commitment”; that is, if it is made with some reservations, meaning, that the person who makes it believes that further inquiry may require her to change her mindFootnote 16 (Frankfurt 1988, 21; 168).

5 Free will, autonomy, responsibility, and their interrelations

Below, I illustrate the implications of adopting Frankfurt’s theory of autonomy in attributing responsibility in DBS patients’ cases in order to demonstrate their tight interrelation. Before that, however, it is crucial to outline the relationship between free will, autonomy and responsibility on a meta-theoretical level. There are philosophers who go so far as to define “free will” as “the strongest control condition—whatever that turns out to be—necessary for moral responsibility” (Dennett, 2004; Fischer, 1994; Mele, 2006; Wolf, 1990). In his influential work, Frankfurt (1969) presented a series of thought experiments that became known as “Frankfurt cases”. They are meant to show that responsibility does not require one of the components that most conceptions of free will postulate—the ability to do otherwise—and furthermore, that what matters for being morally responsible is the source of action. Thus, Frankfurt’s theory is regarded as an account of sourcehood; accounts of this kind lay stress on self-determination. In these views, in order to be the source of action, a person must self-determine her action. For Frankfurt, self-determination of a person means that she is guided by attitudes enabling her for the identification of her higher-order volitions with her lower-level desires (Frankfurt, 1988). As the idea of self-determination lies at the core of the concept of autonomy, Frankfurt’s account and its ilk are currently categorised as theories of autonomy (Dworkin, 1988), even though they were originally developed as a concept of free will (Frankfurt, 1971). For this reason, in this paper I will take not free will, but instead, autonomy as the strongest control condition—whatever that turns out to be—necessary for moral responsibility.Footnote 17

Now, to see how Frankfurt’s theory of autonomy can be applied in attributing moral responsibility in DBS patients, consider simplified version of DP’s case presented by Sharp and Wasserman (2016):

A 63 year old patient with Parkinson’s underwent bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus (STN). One month postoperatively, the patient began gambling heavily. He was not informed about such risks; none were known at the time of his procedure. Before the surgery, according to his wife and children, he “used to be ‘as stingy as a Dutchman,’” and incredibly frugal with his money. Because of his increasing gambling debts, “the house had to be sold and his wife wanted a divorce.” One week after switching off the stimulation, his gambling ceased, and he "was able to sit in a cafe with spare money in his pocket ignoring the slot machine.” However, when stimulation was reactivated, the patient again began “buying scratch cards".

Sharp and Wasserman propose the assumption that DP’s gambling was not strictly compulsive, that is, that he is not the subject of irresistible desire to gamble, but he is just strongly inclined to do it. In such circumstances, one could still ask whether DP is responsible for his behaviour as in all compatibilists’ accounts, the answer for this question depends on further facts about this case. For this reason, consider two further hypothetical variants of DP’s case. In the first variant, Dutch Patient I (DP I) has developed strong inclinations to gamble as a result of DBS’s impact, even though he still considered this inclination contemptible. In the second case, DBS also triggered a strong urge to gamble in the patient (DP II). However, in this case, despite the fact that DP II also lost his money, he still thought that the excitement from betting was worth it, and did not condemn his dispositions. The application of Frankfurt’s model assigns moral responsibility in the second case, but does not attribute it to DP I because his higher-level volitions are in conflict with his lower-level desires; in the case of DP II, they are congruent.

However, various scholars argue that Frankfurt’s model of autonomy is problematic due to its internalist and non-historical character. Internalist accounts postulate that internal psychological scrutiny of the attitudes that determine a given action is both necessary and sufficient for establishing whether a person is morally responsible for her action. This is problematic since, in Frankfurt’s terms, what matters for moral responsibility is the relationship between an agent’s effective first-order desires and her second-order volitions; thus, a person could be responsible for an action that flows from volitions that could be traced back to forces outside of this person. But it seems intuitively problematic that a person should be responsible for an action that flows from mental states which have their origins in exterior forces. Thus, a proper account of moral responsibility seems to also require a diachronic, historical dimension allowing to trace back whether a person’s past restricts internal sourcehood of her actions.

In contrast to the non-historical character of Frankfurt’s account, consider the historicist approach.Footnote 18 For historical accounts, the person must have had (or not have had) a certain type of history in order to be responsible for an action. The crucial issue for all historicists’ approaches concerns the question of what kind of history counts as reducing moral responsibility; historicists usually insist that a person is not responsible for an action flowing from mental states that can be traced back to external forces, and more specifically, they argue that particularly problematic histories involve external influences that bypass a person’s capacities for rational control (De Marco, 2019; Mele, 2008, 2013). Historicism offers a better accounting than non-historicist theories for our intuitions of feeling disposed to reduce the responsibility of a person whose character was deformed by external events, from child abuse to indoctrination (Johansson et al., 2014), as well as of our insistence on so-called “tracing cases”, that is, an intuition that it is relevant to pay attention to the question of whether a person’s past restricts her from being responsible for present mental states in assessing her responsibility for present actions (Shaw, 2014).

Recently, Sharp and Wasserman (2016) substantially contributed to the debate between proponents of historicist and non-historicist approaches by proposing a theory of the latter kind, attempting to ground judgements of what kinds of histories matter for the purpose of a practice of diminishing responsibility in cases of DBS patients. They based their model on the influential theory of autonomy introduced by Christman (2011). Contrary to Frankfurt’s approach, which requires actual reflective endorsement and positive attachment to first-order desires—authenticity, Christman’s theory (2011, 2013) imposes negative and hypothetical conditions. In order for a person to be autonomous, it requires that she does not repudiate given features of the self (e.g., first-order desires), and makes a claim how she must react were she to reflect on these features. Christman considers that a person is autonomous: “[...] if she would not be alienated from the element, were she to engage in sustained reflection on it, in light of a minimally adequate account of its origins, and in absence of reflection distorting factors […]”. Alienation, in this view, is not only a failure of endorsement, but involves both a feeling of being constrained by the desire and the second-order desire to repudiate this feeling, too. It is therefore opposite to authenticity. Here, again, one may observe how strictly intertwined are concepts of authenticity and autonomy—independent of whether it is a non-historicist or historicist approach.

Building on Christman’s conception of autonomy, Sharp and Wasserman constructed a theory of responsibility, the history-sensitive reflection view (HSRV). They claim that a person is fully morally responsible for actions stemming from her psychological states (PS) only if she is competent, that is, if she has the ability of critical reflection, self-control, and reason-responsiveness among others; this person also has to fulfil hypothetical reflection conditions:

-

1)

Were the person to engage in sustained critical reflection over a variety of conditions in light of the historical processes (adequately described) that gave rise to PS,

-

2)

she would not be alienated from PS in the sense of feeling and judging that PS cannot be sustained as part of an acceptable autobiographical narrative organised by her diachronic practical identity, and

-

3)

the reflection being imagined is not constrained by reflection-distorting factors.

It is worth emphasizing that, unlike some other historicist approaches (e.g., Mele, 2001), Sharp and Wasserman do not regard any specific history as preserving or reducing moral responsibility, but subordinate it to about whether the person would hypothetically repudiate desires arising from a history. Thus, the result of the hypothetical reflection, not the actual history, is decisive in assigning moral responsibility in HSRV.

Through the lens of HSRV, DP I would not be held responsible for his actions. He actually expresses disapproval of his first-order desires to gamble; obviously, this expression is not decisive for HSRV. However, it can serve as an indicator that if he were to engage in hypothetical and critical reflection in light of the fact that this particular desire stemmed from DBS’s influence, he would most likely feel alienated from it. The answer to the second point is not so straightforward; if DP II would not realise that his new dispositions were triggered by DBS, then he would not meet the condition of critical reflection due to a lack of knowledge required to engage in critical reflection. If, though, knowing that these dispositions emerged due to DBS, he nonetheless would continue to endorse them without feeling alienated from them, and moreover, this act would not stem from reflection-distorting factors of DBS, responsibility might be assigned to DP II.

HSRV allows for more fine-grained considerations and more intuitive results in an analysis of cases of DBS patients than non-historicist models of responsibility (e.g., Frankfurt’s account). In Sharp and Wasserman’s account, diminishing moral responsibility due to altered psychology depends on whether a person would be alienated from an act under adequate hypothetical reflection in light of personal history. However, the fact that moral responsibility in HSRV always depends on the result of hypothetical reflection raises the following epistemic concern: if responsibility cannot be directly read from an agent’s history of psychological modification, when will judgements reducing responsibility be accurate?

In Sharp and Wasserman’s view, several features of modification and reactions are relevant indicators in making that determination: abruptness of the change, the magnitude of the change, and the circumstances of the alteration. Sharp and Wasserman regard them as a rule of thumb to ease the epistemic burden of establishing responsibility in actual cases. Although there is no doubt that these rules can serve as useful guidance in informing our decisions in moral responsibility assessments, the degree to which a person’s responsibility is affected by the particular modification, or depending on their reaction still needs to be clarified. Furthermore, as De Marco (2019) argues, HSRV is intended to be only part of an account of responsibility as the full-fledged theory will have to account for more, e.g., the agent’s knowledge of, or culpable ignorance of, the relevant moral features of a situation, or the agent’s level of control at the time of an action. Despite these problems, by bringing together philosophical debates on compatibilism and practical debates about responsibility in DBS cases, Sharp and Wasserman’s work has made advances in illuminating and sharpening issues in both. As a result, progress in specifying more fine-grained conditions for moral responsibility assessments has been made thanks to HSRV. Yet, as indicated above, more work will be required in order to further clarify HSRV, and develop it into the full-fledged theory of moral responsibility capable of addressing complex ethical issues concerning DBS treatments.

6 PTS, authenticity, autonomy, and responsibility—Situating moral aspects

In the previous sections, I discussed how PTS relates to the potential risks associated with DBS; how these threats relate to authenticity, autonomy and responsibility; and how moral aspects relate to each other. It is necessary, however, to outline one more relationship in order to properly situate authenticity, autonomy and responsibility in the context of PTS. Thus, in the following section, I will discuss how moral aspects relate to PTS.

The first point that could be made in this context is that moral aspects do not seem to be the same kind of contributories to self-patterns as other aspects, such as the experiential, affective, and cognitive ones. Their role seems to be a more complex one; they appear to be the lens through which a self-pattern constituting a particular self may be evaluated.Footnote 19 Such an interpretation seems to be especially apt regarding the concept of authenticity: a person evaluates some of a particular self-pattern as authentic (e.g., by wholeheartedly endorsing it) and others as alienating. Such a position would explain some statements of DBS patients experiencing alienation, such as “I don’t feel like myself anymore,” or “I haven’t found myself again after the operation.” (Schüpbach et al., 2006) or “I feel like I am who I am now. But it’s not the me that went into the surgery […] No I can’t be the real me anymore—I can’t pretend.” (Gilbert et al., 2017), by postulating that these are judgements about inauthenticity of a particular self-pattern.

In such reports of self-alienation (or self-estrangement) by DBS patients, changes concerning affective, behavioral, intersubjective, cognitive, normative, and narrative aspects seem to be particularly relevant and are mentioned especially often. For instance, one of the patients studied by Schüpbach et al. (2006) reported that “Now I feel like a machine, I’ve lost my passion. I don’t recognize myself anymore.” Gilbert et al. (2017) revealed a similar case of experiencing inauthenticity due to changes in affective aspects: “I would revert to a state of hysterics or something like that much more easily than I would normally have done […] I felt like I had lost my true self, it was way behind me.” Gilbert (2018) categorized other types of self-changes associated with self-estrangement as changes in activities and socio-family dynamics. They also can be easily mapped across aspects of the PTS list: the former are changes in behavioral aspects and the latter may be categorized as changes in the intersubjective and normative as well as narrative aspects. From the perspective of PTS, the case of Patient 4 is particularly informative:

Patient 4: “My family say they grieve for the old [me] […]

Interviewer: And what have your children said to you about the difference that they’ve seen before and after?

Patient 4: Yes, they said they don’t recognise me

Interviewer: And in what way don’t they recognise you?

Patient 4: That I am so impulsive and seem to change my mind all the time” (Gilbert, 2018).

This case is a clear empirical manifestation of PTS’s crucial theoretical claim that what constitutes the self “is a pattern, a dynamical gestalt, and what is important is the connectivity and the dynamical relations of the self-aspects” (Daly & Gallagher, 2019). In the case of Patient 4, impulsivity (affective aspects) and decreased conscientiousness, that is, carelessness (cognitive aspects, specifically personality traits) manifested by his erratic behavior (behavioral aspects) has consequences for intersubjective and normative as well as narrative aspects—the family of the patient does not recognize him as the same person they knew before DBS, as he acknowledged in his self-narrative.

What is even more valuable for showing theoretical advantages of PTS is, however, that Patient 4’s first-personal phenomenological account of how he feels about and experiences DBS therapy differs from the third-person perspective of his relatives. He explicitly states: “I don’t feel different at all. Some people said to me that I am a bit different.” Gilbert et al. (2017) explain this disparity by stating that the “epistemic role of first-personal perspective may be limited” and that “families and social context are an essential measurement of how patients are experiencing potential estrangement, even if patients do not perceive it”, in effect questioning the consistency of patient’s narrative. However, by applying PTS enriched with moral aspects to this case, we may gain—as I will argue—both theoretical underpinnings of why it is the case at all that these perspectives may vary, as well as a different explanation than the “self-deception hypothesis” proposed by Gilbert and colleagues.

Before elaborating on this, however, it is necessary to spell out in more detail the relationship between PTS, authenticity, and other moral aspects. I stated above that authenticity could be understood as the lens through which one evaluates one’s self-pattern. Such a claim could suggest, however, that PTS implicitly assumes some kind of dualism—that there is someone, the self, evaluating whether a particular self-pattern is authentic or not. However, such a reading would be misleading and contrary to the aims and intentions of PTS’s authors. According to PTS, there is no metaphysically independent “thing-like” self to be found outside of the dynamically interrelated aspects arranged in the self-pattern; rather, “selves operate as complex systems that emerge from dynamical interactions of constituent elements. The dynamical relations or interactions among the various factors are important for defining the pattern as a dynamical gestalt that can change over time” (Daly & Gallagher, 2019). It is also worth emphasizing in the context of further considerations that these elements or aspects may have different weights in defining features of the self-pattern. This leads to a question, what is the relationship between PTS and moral aspects of the self?

I suggest that authenticity, autonomy and responsibility are products of dynamical interactions of self-aspects that have first-person experiential components and are ultimately expressed in the narrative. As Daly and Gallagher (2019) state:

Self-narratives in some sense reflect, explicitly in content, or implicitly in form, all of the other aspects of the self-pattern. Narrative is thus a means of retrieving, disclosing, temporally mapping, and connecting all the other aspects. […] Indeed, we may learn about other aspects of the self-pattern precisely through a patient’s narrative, not only in terms of narrative content (what the patient tells us about herself), but also in terms of narrative form (how the patient does the telling).

Different self-aspects may be relevant contributories (and these contributions can have different weights) for generating the first-personal experiences and narratives that result in our conceptualizations of authenticity, autonomyFootnote 20 and moral responsibility—e.g., as discussed above, affective, behavioral, intersubjective, cognitive, normative, and narrative aspects seem to be crucial contributories for authenticity.

For autonomy, other aspects may also be crucially important: minimal experiential aspects, such as the sense of agency; some other cognitive aspects, such as the ability to form second-order volitions about one’s desires.Footnote 21 As the concept of moral responsibility is tightly interconnected with autonomy, the aspects associated with autonomy above also seem to be crucial in assessing responsibility. Moreover, in the case of moral responsibility, additional factors, such as other dimensions of affective and normative aspects, may hold great relevance. As Strawson (1962) famously argues, our practices of assigning responsibility are grounded in the system of human reactive attitudes, such as moral resentment, indignation, guilt, and gratitude. Reactive attitudes, in turn, are driven by affective aspects as they are kind of emotional reactions to situations that usually involve normative transgressions—both in first-person assignments of responsibility (e.g., driven by guilt) as well as in third-person ones (e.g., driven by moral resentment or indignation). This shows that judgments of moral responsibility require interconnections of affective and normative aspects of the self, as one requires normative aspects, such as values, to evaluate whether an action is morally transgressive—as well as reflective capacities of narrative aspects in order to both make such evaluation and to even internalize a value. Thus, the potential of the self to experience and judge others morally responsible is also a product of complex interplay between various self-aspects.

I would like to also emphasize that, from an ethical standpoint, assessments of moral responsibility should necessarily take into account cognitive, behavioral, and narrative aspects associated with autonomy (e.g., the ability to form intentions, be responsive to reasons, choose both deliberately and rationally, and bring these choices into effect), and—in some influential (and more “liberal”) accounts, such as Frankfurt’s approach or HSRV—aspects associated with authenticity (e.g., the ability to make choices consistent with one’s acceptable autobiographical narrative organised by the diachronic practical identity postulated by HSRV). Without including these aspects, the practice of holding persons morally responsible would be unjust, as it would be reduced to checking if a person has followed moral principles internal to the community—moral principles that were produced by reactive attitudes of its members and practices that arise from them, neither of which require nor admit of rational justification (see Sharp & Wasserman, 2013). Thus, not taking into account self-aspects associated with autonomy (or/and authenticity) would result in a situation in which persons would be held responsible for morally arbitrary reasons and for what is ultimately beyond their control, which would be fundamentally unjust.Footnote 22 It is worth noting that advances made by HSRV are represented by its ability to specify more fine-grained conditions of moral responsibility assessments by referring to the aspects of the self associated with both autonomy and authenticity.

What must be emphasized, and is of crucial importance in the context of the relationship between PTS, authenticity, autonomy, and responsibility, is that narrative aspects play a crucial, dual role in this regard. First, narrative does not differ from any other aspect of PTS, in that a change in narrative may recursively induce a change in other aspects (and vice versa), and, consequently in the self-pattern, “since any change in any of the elements of the self-pattern may have an effect on the pattern as a whole” (Daly & Gallagher, 2019). Second, however, unlike the other aspects, narrative is reflective of other elements of the self-pattern. In effect, narrative is a window allowing investigation of the details of the self-pattern, in both the first and third person—“this is the role of narrative that allows for its formalization in the second-person phenomenological interview” (Daly & Gallagher, 2019).

Daly and Gallagher (2019) argue that the use of narrative in therapeutic contexts, such as in phenomenological interviews, is second-personal or intersubjective “in the sense that much of what the patient discovers and expresses in her narrative emerges only in the expression of it to the other person, the interviewer-physician, who is attempting to understand. In such cases, we can say that the processes that lead to these detailed descriptions or narratives are not private mental procedures, but intersubjective, interactive accomplishments.” I think a similar case can be made regarding patients and their relatives (including doctors, nurses, psychotherapists, etc.) who report disruptions of authenticity, autonomy and responsibility induced by DBS. There is certainly a phenomenological first-personal component which guides patients’ descriptions and narratives concerning their (in)authenticity, (lack of) autonomy, or (lack of) moral responsibility to some extent. However, these descriptions are ultimately confronted with the narratives of their closest social surroundings, and as such, they enter an intersubjective, negotiable sphere. It makes the final result of such confrontations—judgements and narratives concerning moral aspects of the self—an interactive accomplishment. When specific narratives gain reasonable, intersubjective acceptance (which may not always be the case), in some instances they may even create a feedback effect and modify other aspects of patients’ self-patterns, ultimately changing their first-person experience. In other words, patients by reflecting on their self-aspects through the lens of accepted narratives concerning (in)authenticity, (lack of) autonomy, or (lack of) moral responsibility may recursively modify their phenomenology.

With this in mind, I can now return to the case of Patient 4. The disparity between his first-person and the third-person account of his family may be a result of different weights of various self-aspects in constituting an authentic self-pattern. That is, intersubjective, normative, and narrative (e.g., socio-family dynamics), or even affective aspects (e.g., increased impulsivity), may not be as crucial for an authentic what-it’s-likeness as cognitive aspects (e.g., memory), or experiential aspects (e.g., a sense of mineness), that were plausibly undisrupted by DBS in this patient. Thus, it can be that this particular self-pattern is simply not experienced as self-alienating from the first-personal perspective, as changes in affective, intersubjective, normative, and narrative aspects are not sufficiently “convincing” to lead Patient 4 to recognize his “new” self-pattern as inauthentic. Arguably, if disruptions of some of these aspects were above some threshold, inauthenticity could occur. In this regard, inauthenticity (and DBS-induced disruptions in other moral aspects of the self, autonomy and responsibility) can be similar to psychological disorders such as schizophrenia or depression—psychological disorder may be diagnosed only when sufficiently many aspects of the self-pattern characteristic of a given disease change above certain threshold (see Daly & Gallagher, 2019).

These considerations show why PTS could be a good candidate to explain why the first- and third-person perspectives may differ in reporting self-alterations of DBS patients. They also are in conflict with Gilbert et al.’s (2017) claims that the “epistemic role of first-personal perspective may be limited” and that the family perspective has epistemic advantages. It is the patient who has an access to the final product of dynamical interactions of aspects that build his self-pattern; his relatives, on the other hand, can only base their narratives on third-personal observations of his behavior. It is true, obviously, as Gilbert et al. (2017) rightly notice, that “relatives are often more sensitive to alterations in self than the patients themselves.” For this reason, their narratives regarding patients’ (in)authenticity, (lack of) autonomy, or (lack of) responsibility may be especially convincing when they are confronted with the patients’ descriptions and narratives, and, as such, they can have great impact on the final narrative that is internalized by the patients. In light of these considerations, however, it is the patient whose epistemic access to disruptions of the self-aspects is the most informative. Therefore, we should not assume DBS patients are self-deceptive regarding their narratives as long as the opposite is proved beyond any doubt.

7 Summary

The considerations outlined above show that a version of PTS enriched with moral aspects may lead to a novel understanding of DBS effects on patients’ selves. My proposal draws from works of Dings and de Bruin (2016), Gallagher (2018), Gallagher and Janz (2018), Gallagher and Daly (2018), and Daly and Gallagher (2019), extending previous considerations in important ways. First, it expands PTS with additional moral aspects, such as authenticity and moral responsibility. Second, it shows how authenticity, autonomy and moral responsibility relate to each other and how each of them relates to PTS. In the latter regard, I demonstrate that narrativity is crucial to situate not only autonomy, as noted by, e.g., Gallagher and Daly (2018), but also authenticity and moral responsibility in the PTS framework. Moreover, I also propose that narrative is pivotal to map these moral aspects across the numerous other aspects of the self-pattern, such as the behavioral, affective, cognitive, intersubjective, and normative ones. Additionally, I show why and how narrative plays a dual role in these processes—it simultaneously contributes to the self-pattern and may recursively modify aspects of the self (including the moral ones) as well as reflects the self-pattern. Finally, I apply this enriched model to the analysis of the case of Patient 4, demonstrating innovative ways of understanding DBS effects on the self, and propose how these deliberations should inform neuroethical considerations and therapeutic decisions.

Applying this extended model can help to address relevant issues, such as explaining disparities between patients’ and relatives’ narratives and attitudes towards DBS therapy. It can also help in deciding which of these narratives should have priority in informing therapeutic decisions, and justify why it should be so in particular clinical cases. Although, as I have demonstrated, PTS-moral aspects account does justice to the intersubjective, relational dimension of the concepts and narratives regarding authenticity, autonomy (see also Gallagher, 2018) and moral responsibility, it also emphasizes a special epistemic value of the first-person perspective of DBS patients, as their access to the final product of dynamical interactions of self-aspects seem to be, in some relevant respects, privileged. For this reason, we should be especially sensitive and pay special attention to the patients’ phenomenological reports, as they are uniquely informative regarding potential disruptions in self-patterns that lead to diminished authenticity, autonomy, or moral responsibility.

Although PTS still needs further refinement—ontological issues are relevant from neuroethical perspective, particularly the one regarding the persistence question—overall, it seems to be a better candidate for understanding the broader range of consequences of DBS for patients’ selves than other proposed models of the self. Moreover, the enrichment of PTS with the moral aspects of the self proposed in this article also enhances the explanatory power of PTS, as it allows inclusion of relevant aspects of the self that could be previously missed by this framework. Thus, although further discussion is needed not only regarding the PTS framework and its relation to DBS therapy, but also the very concepts of moral aspects (i.e., authenticity, autonomy and responsibility),Footnote 23 the inclusion of moral aspects in the PTS framework is a step forward for neuroethics. It may, as I have argued, deliver tools to better diagnose disruptive self-aspects and self-patterns indicative of DBS’s effects. Finally, it is also worth emphasizing that further discussions on the role of moral aspects in the PTS framework will potentially allow us to understand in greater detail the complicated dynamics of changes to the self-pattern, revealing answers to questions concerning the very nature of the human self.

Change history

04 December 2020

A funding note has been added.

Notes

See Agid et al., 2006; de Haan et al., 2013, 2015; Gilbert et al., 2017; Gilbert & Viaña, 2018; Gilbert, 2018; Haahr et al., 2013; Hariz et al., 2011; Houeto, 2002; Lewis et al., 2015; Liddle et al., 2018; Mathers et al., 2016; Pham et al., 2015; Scaratti et al., 2020; Schüpbach et al., 2006; Smeets et al., 2018; Thomson et al., 2019, 2020.

For a discussion of this point see e.g., Mecacci and Haselager, 2014.

For a similar attempt—demonstrating the interrelations of these concepts but with the exclusion of responsibility and inclusion of personal (narrative) identity—through the lens of a different theoretical framework (of relational autonomy) see Goddard (2017).

This point was also made in the recent article of Pugh et al. (2018): “Autonomy is also typically understood to be related to a number of other important values including personal identity, authenticity, agency, and responsibility.”

“Gallagher articulates his pattern theory at the meta-theoretical level, where it aims to describe every aspect that can be included in any particular pattern theory of self, and map out all possible pattern theories of self.” (Dings & de Bruin, 2016).

De Haan et al., (2013) are also authors of one of the models of the self applied in the context of DBS-induced changes in patients. They propose an enactive, affordance-based account that aims to integrate persons’ experience of the world, person-side of the interaction, characteristics of the way in which persons relate to the world, as well as attitudes that persons take towards DBS-induced changes. In their considerations, de Haan et al. focus on the analysis of patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder being treated with DBS.

My thanks to a reviewer for this insight.

See Brown et al., 2016a and b; Clausen, 2010; Douglas, 2014; Gilbert, 2015; Gilbert et al., 2018a and b; Glannon, 2014a and b; Goddard, 2017; Goering, 2015; Goering et al., 2017; Kellmeyer et al., 2016; Klein, 2015; Müller & Walter, 2010; Pugh et al., 2018; Unterrainer & Oduncu, 2015; Wardrope, 2014.

But see also Lippert-Rasmussen (2003), who divides identification accounts into accounts of “authority” and “authenticity”, categorizing Frankfurt’s approach as the former.

Wolf (1987, 1990) also points to a close relationship between Frankfurt’s account of autonomy and moral responsibility. She characterises Frankfurt’s approach as a precursor of “deep self views” of responsibility. Although various deep self views differ from each other, they all agree that a person is morally responsible for an action if it expresses her deep self (Sripada, 2016). In terms of Frankfurt’s account, we can attribute moral responsibility to a person if she is not simply moved by her strongest desires, but identifies with the desires that move her because they are endorsed by her higher-order volitions—such demeanour express deep self of that person.

However, as Bublitz and Merkel (2013) argue, historicists also assume internalism, and thus fail to recognise the relational character of moral responsibility. For example, they fail to adequately explain cases of coercion, overlooking the fact that coercion undermine the person’s responsibility not because of her internal states, but rather because of “normatively shared relations” between the coercer and the coerced—namely, that the coercer has violated the rights of the coerced.

Words of thanks to a reviewer for this insight.

See also Gallagher and Janz's (2018) attempt to map autonomy across the numerous aspects of the self-pattern.

Which, e.g., for Frankfurt is the equivalent of autonomy; and narrative aspects allowing for self-reflection that informs decision-making process (see also Gallagher, 2018).

I must emphasize, however, that although it may be that moral responsibility is a concept that most self-patterns produce infallibly—and there may be a very well evolutionary rationale for this—as evidenced, e.g., by the fact that humans are held responsible for their deeds in (almost) every culture, moral responsibility could be in fact metaphysically unjustifiable (that is, all compatibilist positions such as HSRV or deep-self views are false), and, as such, it is always fundamentally unfair to hold oneself (or others) morally responsible. A family of views defended by a group of influential philosophers (see Caruso, 2018)—skepticism of free will and moral responsibility (or hard incompatibilism)—has actually recently argue that it is the case. They argue that best philosophical and scientific theories points out that: “[w]hat we do and the way we are is ultimately the result of factors beyond our control, whether that be determinism, chance, or luck, and because of this agents are never morally responsible in the sense needed to justify certain kinds of desert-based judgments, attitudes, or treatments—such as resentment, indignation, moral anger, backward-looking blame, and retributive punishment.” Hence, as, e.g., HSRV explicitly argues for backward-looking moral responsibility: “[t]o say that an agent is morally responsible is to say that she is an apt target for certain ‘reactive attitudes’ such as praise, resentment, blame, and gratitude, which play a critical role in our moral practices” (Sharp and Wasserman, 2016), it would have to satisfactorily explain how someone could take moral responsibility for factors beyond one’s control. For example, according to HSRV, DP would have to take moral responsibility for a disposition to (not) be alienated from the desire to gamble (DA) in the sense of feeling and judging that this desire cannot be sustained as part of an acceptable autobiographical narrative organised by his diachronic practical identity (were he to engage in sustained critical reflection over a variety of conditions in light of the historical processes that gave rise to the desire to gamble) either despite the fact DA stems from factors outside of DP’s control, such as his genetic makeup, early environment, and the opportunities that present himself (constitutive lack), or because DA is significantly influenced by circumstantial factors outside of DP’s control at or near the time of action, such as his mood, what reasons happen to come to him, situational features of the environment (present lack), or despite both. So, it seems that in his feeling or judgement of being alienated from the desire to gamble, DP would express attitudes, endowments, or values explained by constitutive luck, or reflecting his present luck, or both; hard incompatibilist would therefore claim that attributing to DP moral responsibility in such circumstances is not well justified and unjust. As I mentioned before, however, this critique pose a problem not only for HSRV, but for any compatibilist approach; therefore, it is a matter of more general discussion between compatibilists and hard incompatibilists (see Caruso, 2012; Levy, 2011).

As evidenced, for example, by the incompleteness of HSRV, one of the most detailed theories of moral responsibility.

References

Agid, Y., Schüpbach, M., Gargiulo, M., Mallet, L., Houeto, J. L., Behar, C., Maltête, D., Mesnage, V., & Welter, M. L. (2006). Neurosurgery in Parkinson’s disease: The doctor is happy, the patient less so? Journal of Neural Transmission Supplementum, 70, 409–414.

Baylis, F. (2013). “I am who I am”: On the perceived threats to personal identity from deep brain stimulation. Neuroethics, 6(3), 513–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-011-9137-1.

Berofsky, B. (1995, September). Liberation from self: A theory of personal autonomy. Cambridge Core; Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527241.

Bhargava, P., & Doshi, P. (2008). Hypersexuality following subthalamic nucleus stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology India, 56(4), 474. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.44830.

Brown, T., Moore, P., Herron, J., Thompson, M., Bonaci, T., Chizeck, H., & Goering, S. (2016a). Personal responsibility in the age of user-controlled neuroprosthetics. In 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Ethics in Engineering, Science and Technology (ETHICS) (pp. 1–12). https://doi.org/10.1109/ETHICS.2016.7560039.

Brown, T., Thompson, M. C., Herron, J., Ko, A., Chizeck, H., & Goering, S. (2016b). Controlling our brains – A case study on the implications of brain-computer interface-triggered deep brain stimulation for essential tremor. Brain-Computer Interfaces, 3(4), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326263X.2016.1207494.

Bublitz, C., & Merkel, R. (2013). Guilty minds in washed brains? Manipulation Cases and the Limits of Neuroscientific Excuses in Liberal Legal Orders. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199925605.003.0014.

Caruso, G. (2012). Free Will and Consciousness: A Determinist Account of the Illusion of Free Will. Lexington Books.

Caruso, G. (2018). Skepticism about moral responsibility. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (spring 2018). Metaphysics Research Lab: Stanford University https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/skepticism-moral-responsibility/.

Christman, J. (2011). The politics of persons: Individual autonomy and socio-historical selves. Cambridge University Press.

Christman, J. (2013). Autonomy. In R. Crisp (Ed.), Southern Journal of Philosophy (p. 281, 293). Oxford University Press.

Christman, J. (2018). Autonomy in moral and political philosophy. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (spring 2018). Metaphysics Research Lab: Stanford University https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/autonomy-moral/.

Clausen, J. (2009). Man, machine and in between. Nature, 457, 1080–1081. https://doi.org/10.1038/4571080a.

Clausen, J. (2010). Ethical brain stimulation - neuroethics of deep brain stimulation in research and clinical practice: Ethical brain stimulation. European Journal of Neuroscience, 32(7), 1152–1162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07421.x.

Craig, J. N. (2016). Incarceration, direct brain intervention, and the right to mental integrity – A reply to Thomas Douglas. Neuroethics, 9(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-016-9255-x.

Daly, A., & Gallagher, S. (2019). Towards a phenomenology of self-patterns in psychopathological diagnosis and therapy. Psychopathology, 52(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499315.

de Bruin, L., Dings, R., & Gallagher, S. (2017). The multidimensionality and context dependency of selves. AJOB Neuroscience, 8(2), 112–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2017.1320327.

de Haan, S. (2017). Missing oneself or becoming oneself? The difficulty of what “becoming a different person” means. AJOB Neuroscience, 8(2), 110–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2017.1320330.

de Haan, S., Rietveld, E., Stokhof, M., & Denys, D. (2013). The phenomenology of deep brain stimulation-induced changes in OCD: an enactive affordance-based model. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00653.

de Haan, S., Rietveld, E., Stokhof, M., & Denys, D. (2015). Effects of deep brain stimulation on the lived experience of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: In-depth interviews with 18 patients. PLoS One, 10(8), e0135524. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135524.

De Marco, G. (2019). Brain interventions, moral responsibility, and control over One’s mental life. Neuroethics, 12(3), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-019-09414-7.

Dennett, D. C. (2004). Freedom evolves. Penguin.

Dings, R. (2019). The dynamic and recursive interplay of embodiment and narrative identity. Philosophical Psychology, 32(2), 186–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2018.1548698.

Dings, R., & de Bruin, L. (2016). Situating the self: Understanding the effects of deep brain stimulation. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 15(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-015-9421-3.

Douglas, T. (2014). Criminal rehabilitation through medical intervention: Moral liability and the right to bodily integrity. The Journal of Ethics, 18(2), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-014-9161-6.

Dubljević, V. (2013). Autonomy in Neuroethics: Political and not metaphysical. AJOB Neuroscience, 4(4), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2013.819390.

Dworkin, G. (1976). Autonomy and behavior control. The Hastings Center Report, 6(1), 23–28.

Dworkin, G. (1988). The theory and practice of autonomy. Cambridge University Press.

Eich, S., Müller, O., & Schulze-Bonhage, A. (2019). Changes in self-perception in patients treated with neurostimulating devices. Epilepsy & Behavior, 90, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.10.012.

Fischer, J. M. (1994). The metaphysics of free will: An essay on control. Blackwell.

Fitzgerald, P. B., & Segrave, R. A. (2015). Deep brain stimulation in mental health: Review of evidence for clinical efficacy. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(11), 979–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415598011.

Frankfurt, H. (2006). Taking Ourselves Seriously & Getting it Right. Bibliovault OAI Repository, the University of Chicago Press.

Frankfurt, H. G. (1969). Alternate possibilities and moral responsibility. Journal of Philosophy, 66(23), 829.

Frankfurt, H. G. (1971). Freedom of the will and the concept of a person. The Journal of Philosophy, 68(1), 5–20. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/2024717.

Frankfurt, H. G. (1988). The importance of what we care about: Philosophical essays. Cambridge University Press.

Frankfurt, H. G. (1998, November). Necessity, volition, and love. Cambridge Core; Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511624643.

Friedman, M. F. (2003). Autonomy. Social Disruption, and Women. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195138503.003.0005.

Gallagher, S. (2013). A pattern theory of self. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00443.

Gallagher, S. (2018). Deep brain stimulation. Self and Relational Autonomy. Neuroethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-018-9355-x.

Gallagher, S., & Daly, A. (2018). Dynamical relations in the self-pattern. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00664.

Gallagher, S., & Janz, B. (2018). Solitude, self and autonomy (pp. 159–176). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv8xnhwc.11.

Gilbert, F. (2015). A threat to autonomy? The intrusion of predictive brain implants. AJOB Neuroscience, 6(4), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2015.1076087.

Gilbert, F., Goddard, E., Viaña, J. N. M., Carter, A., & Horne, M. (2017). I miss being me: Phenomenological effects of deep brain stimulation. AJOB Neuroscience, 8(2), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2017.1320319.

Gilbert, F., O’Brien, T., & Cook, M. (2018a). The effects of closed-loop brain implants on autonomy and deliberation: What are the risks of being kept in the loop? Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 27(02), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180117000640.

Gilbert, F., & Viaña, J. N. M. (2018). A personal narrative on living and dealing with psychiatric symptoms after DBS surgery. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, 8(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2018.0024.

Gilbert, F. (2018). Deep brain stimulation: Inducing self-estrangement. Neuroethics, 11(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-017-9334-7.

Gilbert, F., Viaña, J. N. M., & Ineichen, C. (2018b). Deflating the “DBS causes personality changes” bubble. Neuroethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-018-9373-8.

Gisquet, E. (2008). Cerebral implants and Parkinson’s disease: A unique form of biographical disruption? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 67(11), 1847–1851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.026.

Glannon, W. (2009). Stimulating brains, altering minds. Journal of Medical Ethics, 35(5), 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2008.027789.

Glannon, W. (2014a). Philosophical reflections on therapeutic brain stimulation. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2014.00054.

Glannon, W. (2014b). Neuromodulation, agency and autonomy. Brain Topography, 27(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-012-0269-3.

Goddard, E. (2017). Deep brain stimulation through the “Lens of agency”: Clarifying threats to personal identity from neurological intervention. Neuroethics, 10(3), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-016-9297-0.

Goering, S. (2015). Stimulating autonomy: DBS and the Prospect of choosing to control ourselves through stimulation. AJOB Neuroscience, 6(4), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2015.1106274.

Goering, S., Klein, E., Dougherty, D. D., & Widge, A. S. (2017). Staying in the loop: Relational agency and identity in next-generation DBS for psychiatry. AJOB Neuroscience, 8(2), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2017.1320320.

Goethals, I., Jacobs, F., Van der Linden, C., Caemaert, J., & Audenaert, K. (2008). Brain activation associated with deep brain stimulation causing dissociation in a patient with Tourette’s syndrome. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 9(4), 543–549.

Haahr, A., Kirkevold, M., Hall, E. O. C., & Østergaard, K. (2013). ‘Being in it together’: Living with a partner receiving deep brain stimulation for advanced Parkinson’s disease - a hermeneutic phenomenological study: Being in it together. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(2), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06012.x.

Hariz, G.-M., Limousin, P., Tisch, S., Jahanshahi, M., & Fjellman-Wiklund, A. (2011). Patients’ perceptions of life shift after deep brain stimulation for primary dystonia-a qualitative study. Movement Disorders, 26(11), 2101–2106. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.23796.

Haworth, L. (1986). Autonomy: An essay in philosophical psychology and ethics. Yale University Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt211qz2c.

Hemm, S., & Wårdell, K. (2010). Stereotactic implantation of deep brain stimulation electrodes: A review of technical systems, methods and emerging tools. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing, 48(7), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-010-0633-y.

Herrington, T. M., Cheng, J. J., & Eskandar, E. N. (2016). Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology, 20.

Hildt, E. (2006). Electrodes in the brain: Some anthropological and ethical aspects of deep brain stimulation. International Review of Information Ethics, 5(9), 33–39.

Houeto, J. L. (2002). Behavioural disorders, Parkinson’s disease and subthalamic stimulation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 72(6), 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.6.701.

Johansson, V., Garwicz, M., Kanje, M., Halldenius, L., & Schouenborg, J. (2014). Thinking ahead on deep brain stimulation: An analysis of the ethical implications of a developing technology. AJOB Neuroscience, 5(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2013.863243.

Johansson, V., Garwicz, M., Kanje, M., Schouenborg, J., Tingström, A., & Görman, U. (2011). Authenticity, depression, and deep brain stimulation. Frontiers in Integrative Neurosci., 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2011.00021.

Kellmeyer, P., Cochrane, T., Müller, O., Mitchell, C., Ball, T., Fins, J. J., & Biller-Andorno, N. (2016). The effects of closed-loop medical devices on the autonomy and accountability of persons and systems. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 25(04), 623–633. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180116000359.

Klaming, L., & Haselager, P. (2013). Did my brain implant make me do it? Questions raised by DBS regarding psychological continuity, responsibility for action and mental competence. Neuroethics, 6(3), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-010-9093-1.