Abstract

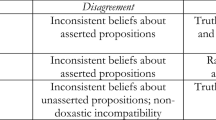

In the recent debate about the semantics of perspectival expressions (predicates of taste, aesthetic adjectives, moral terms, epistemic modals, epistemic terms etc.), disagreement has played a crucial role. In a nutshell, what I call “the challenge from disagreement” is the objection that certain views on the market (i.e., contextualism) cannot account for the intuition of disagreement present in ordinary exchanges involving perspectival expressions like “Licorice is tasty./No, it’s not.” Various contextualist answers to this challenge have been proposed, and this has led to a proliferation of notions of disagreement. It is now accepted in the debate that there are many notions of disagreement and that the search for a common, basic notion is misguided. In this paper I attempt to find such a basic notion underneath this diversity. The main aim of the paper is to motivate, forge and defend a notion of “minimal disagreement” that has beneficial effects for the debate over the semantics of perspectival expressions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are other versions of contextualism as well. For example, one can take the perspective to be that of the group Lisa belongs to, or a generic perspective etc. This variation will not affect the main points of the paper. The same applies to relativism as well.

Absolutist, or invariantist, views about perspectival expressions are also present in the literature. They are, however, a minority. In addition, the focus in this paper is on accounting for disagreement, and absolutist views are not problematic in this respect – although there is some variety in the way disagreement is construed within the absolutist camp. See Wyatt (2018) for a recent non-orthodox absolutist approach to disagreement involving predicates of taste.

The parentheses are meant to signify that the data need not be as simple as the exchange between Bart and Lisa above. Disagreement, faultless or not, can appear as part of longer exchanges, or can stretch over longer periods of time etc. However, I take it to be quite intuitive that the part of an exchange that prompts the intuition of disagreement is something similar to the simple exchange (the word “No” being usually a reliable indication of disagreement). See Kinzel and Kusch (2018) for a recent view on the methodological effect of focusing on simple exchanges like the one above. It is also customary to distinguish between disagreement in state and disagreement in act (Cappelen and Hawthorne 2009): the latter requires some interaction between the disagreeing parties, while the former doesn’t. Disagreement in state is taken to be the more fundamental notion (see, among others, MacFarlane 2014); however, since I focus here on exchanges, I will take disagreement in act as the relevant notion – which is, of course, compatible with disagreement in state having explanatory priority.

See (Zeman 2017) for more details on the various recent contextualist strategies.

Whether this way of framing pluralism about disagreement is ultimately successful is not clear. See (Zeman 2020) for some doubts about MacFarlane’s pluralist approach. This issue, however, is not my present concern.

Among previous attempts at putting forward or discussions of such a notion the following works can be counted: Belleri and Palmira (2013), Baker (2014), Belleri (2014), Coliva and Moruzzi (2014) and, more recently, Worsnip (2019). It will become clear in due course how the notion I propose differs from theirs.

Having said that, I take the indeterminacy of the disagreement data to stem from our current limitation of gathering or interpreting it, and I’m moderately optimistic about the possibility of ultimately coming up, by empirical means, with a definite set of exchanges that should be counted as disagreement. Thus, I take the indeterminacy of the data to be rather temporary. This contrasts with the indeterminacy of the notion of minimal disagreement, which comes, so to speak, by design. See the discussion in section 4.3.

As I mentioned, in the literature there is a commonly accepted distinction between disagreement in act and disagreement in state (Cappelen and Hawthorne 2009). Assuming that this distinction is accepted by the folk, the claim here is that there is no ambiguity left once we fix on one of the two senses. I thank a referee for bringing this motivation to my attention.

Worsnip’s (2019) view is not objectionable on this score, as it is one of his declared aims to include “disagreement in attitude” (expressivists’ favorite notion of disagreement) among the types of disagreement that his notion of “wide disagreement” is supposed to cover. My aim in this paper and Worsnip’s in the paper referred to are very similar. I will briefly engage with his proposal below (section 4.3., footnote 23).

Of course, this assumes that allowing expressivism in the debate is desirable. Doubts about this come from taking expressivism to be a theory about mental states, rather than about the semantic content of utterances like (1). Two things can be said to quell this worry. First, taking expressivism to be a theory about mental states is compatible with taking it to be a theory of semantic contents of utterances, with presumably most of the work to be done being spelling out the connection between these two aspects of the theory. Second, the expressivist authors cited do take themselves to engage with views about the semantic content of utterances like (1) (i.e., contextualism, relativism etc.), precisely in connection to disagreement – which indicates that they take their theory to account for the same phenomenon.

The aim of providing a schema or template for disagreement is also that of Belleri and Palmira (2013), whose lead I follow.

This comes close to Plunkett and Sundell’s (2013) definition “Disagreement Requires Conflict in Content (DRCC): If two subjects A and B disagree with each other, then there are some objects p and q (propositions, plans, etc.) such that A accepts p and B accepts q, and p is such that the demands placed on a subject in virtue of accepting it are rationally incompatible with the demands placed on a subject in virtue of accepting q.” (11). (MD) differs from their definition in that demands placed on subjects are missing, and is thus a more minimal definition.

In what follows, the domain of the variables A, B and C will be quite restricted, for reasons having to do with the nature of the debate I’m concerned with. Thus, the attitudes in conflict to be considered are of two broad types – cognitive and conative, with very few varieties of each (acceptance and rejection on the cognitive side; a general positive and a general negative attitude on the conative side). While more specific attitudes will be considered in section 4.4., this is far from exhausting all the possibilities of conflicting attitudes. Similarly, the types of contents considered are propositional perspective-neutral contents, propositional perspective-specific contents and objects, while the levels of discourse are the semantic, the pragmatic and the implied. No doubt, a more complete project will involve a study of more varieties of disagreement involving more types of each of these elements. I leave pursuing this project for another occasion.

I’m assuming here (alongside expressivists and most of the authors in the debate) that there is no rift between the semantic content of an utterance and the proposition asserted by that utterance. This is, of course, a controversial assumption, but one that I don’t think is harmful in this context.

López de Sa’s rendering of the dialogue isn’t straightforwardly similar the other positions mentioned, given that at the level of presuppositions no disagreement arises. However, due to the uniformizing effect of the presupposition of commonality, disagreement is made possible at the semantic level – that is, Lisa and Bart end up having conflicting attitudes towards the same content (since Lisa and Bart’s standard of taste is the same). This disagreement, at the level of asserted content, conforms to (MD).

The attitudes in conflict need not be doxastic. As Worsnip (2019) argues, all the contextualist attempts to account for disagreement exemplified above can be put in terms of doxastic disagreement, but they need not be. However, this is not problematic for (MD). If you think that, for example, metalinguistic disagreement doesn’t involve doxastic attitudes towards propositions but rather conative attitudes, simply replace ACCEPT and REJECT with PRO and CON. What is important is that they are attitudes in conflict, directed towards the same content.

Also, I have taken some liberty with rendering the non-semantic, second layer content posited by various strategies. If you think that the way I render it in is inaccurate, please replace it with what you think is a better fit for the strategies in question. This shouldn’t affect he points I’m making in this paper. (For a nice discussion of the choices pertaining to at least some of these strategies, see Finlay (2017).

Finally, I note that some of the authors mentioned above are undecided about the pragmatic strategy they ultimately follow, and therefore categorizing their views might be more complicated than I suggested. For example, Zakkou (2019) situates the pragmatically conveyed content either at the level of presuppositions or at the level of implicatures; Marques (2016) is similarly ambivalent; etc.

Using the same model, disagreement can be seen as arising at the level of implied content as well. The disagreement between Lisa and Bart in our main exchange could thus be seen as arising at the level of the contents implied by each utterance. What those contents are I take to be a highly contextual matter. For example, if we assume that Lisa and Bart have the common goal of buying sweets that they both like, a contextualist rendering of the exchange would be the following (with ‘IC’ standing for ‘implied content’):

Contextualism + Implication disagreement:

Lisa: ACCEPT (Licorice is tasty for Lisa)

ACCEPT IC (Lisa and Bart should buy licorice)

Bart: REJECT (Licorice is tasty for Bart)

REJECT IC (Lisa and Bart should buy licorice).

This type of disagreement also conforms to (MD), since it involves conflicting doxastic attitudes directed towards the same implied propositional content. In the same vein, one can render the exchange between Lisa and Bart in which they use the ‘I like’ phrase (section 2) as arising at the level of implied content. Finally, let me note that there is a recent view proposed by Zouhar (2018), according to which disagreement is also (partially) explained in terms of implied content.

Moreover, a similar strategy can be adopted in the case in which disagreement seems to appear with contents that are not contradictory, but nevertheless cannot be both true (in a certain context). For example, if Lisa utters ‘Licorice is tasty’ and Bart answers ‘Nothing here is tasty’, the contents expressed by the two utterances are not strictly speaking contradictory, but the truth of the other precludes the truth of the other (if nothing is tasty, then neither licorice is). The strategy applies in that the disagreement can be seen as arising between the content of Lisa’s utterance and the relevant content implied by Bart’s utterance; we thus get the following rendering:

Lisa: ACCEPT (Licorice is tasty)

ACCEPT IC (Licorice is tasty)

Bart: ACCEPT (Nothing in the relevant location is tasty)

REJECT IC (Licorice is tasty).

Again, this fits with (MD), in that the disagreement consists in conflicting doxastic attitudes directed towards the same implied propositional content.

Another route might be to provide notion of “minimal conflict” that all participants could agree on. Embarking on this route, however, will most likely lead to a replication of the issues already discussed. I thank a referee for requesting clarification on this point.

As an example of new, sui-generis types of attitudes, consider Schroeder’s (2008) attitude of “being for”. While being in essence an expressivist type of attitude, its role is to cover both and thus serve as a common ground between cognitive and conative attitudes. On the other hand, as an example of new, sui-generis type of content consider Gibbard’s (2003) world-plan states. Crucially, neither of these should be taken as a model for the attitudes/contents figuring in (MD). As already made clear, the latter are mere abstractions to be fleshed out by giving values to the variables and not substantial attitudes/contents.

Moreover, the relativist who adopts (MD) will have problems with utterances said to have de se contents – for example, utterances of sentences containing the first person pronoun ‘I’. The intuition of disagreement involving exchanges with ‘I’ is also lacking (‘A: I’m a doctor./B: No, I’m not a doctor.’), and while the contextualist route is open here as well, taking it leads to rejecting de se contents for ‘I’. The more general worry is that, by following that route, all the advantages brought about the postulation of de se contents will be lost.

Let me also note that another type of exchanges used to make the overgeneration point involves the present tense (as well as other tenses and temporal expressions): in exchanges like ‘A (at time t1): Socrates is sitting./B (at time t2): No, Socrates is not sitting.’, the intuition of disagreement is lacking, since A and B consider Socrates as sitting at different times. However, while contemporary temporalists agree with this, they also argue that the intuition of disagreement is present with other (more complex) examples involving the present tense: see, for example, Brogaard’s (2012) firefighter example.

In this, it differs from recent attempts at defining (minimal) disagreement. Authors like Belleri and Palmira (2013), Belleri (2014) and Coliva and Moruzzi (2014) are happy to include relativity to circumstances in their notion of (minimal) disagreement. Also, the first two authors define disagreement in terms of the “accuracy” of acts of acceptance, which makes for a more theoretically sophisticated definition than the austere one proposed in this paper. My notion of disagreement can also be seen as minimal in that it uses very simple tools from the semanticist’s toolkit (notions like content, attitude and semantic level, but not accuracy, circumstance etc.).

To be clear, my aim in the above discussion was not to save relativism (or any view, for that matter) from the objection that it cannot account for disagreement. That it cannot, despite this being one of the main motivations brought in its favor, has been claimed many times in the literature (for a very recent expression of this claim, see Baghramian and Coliva 2020). I myself am sympathetic to the claim that the more substantial notion of disagreement relativists adopt undermines their own case. For the purposes of this paper, this is not a troublesome result. Generalizing the discussion, it merits stressing that the aim of the paper is not to defend any semantic view about perspectival expressions (so that if one such view is problematic, that is fine for the purpose of this paper), but something more basic: to make it possible for the views on the table to be able to have a meaningful debate about disagreement, with (MD) ensuring that none of them is excluded just because of their theoretical commitments and their adherence to a more substantial notion of disagreement.

This is perhaps the right place to discuss Worsnip’s (2019) proposal of a notion of minimal disagreement (the “wide” notion, as he calls it) as interpersonal incoherence. While I’m largely sympathetic to the proposal, I think this view is unsatisfactory for at least two reasons. First, his notion excludes disagreement involving centered contents (in fact, he takes his view on disagreement to be a reduction of the claim that we need centered contents). Worsnip trades here on the idea that there is no intuition of disagreement when the contents of certain utterances are centered – for example, in the case of the pronoun ‘I’. However, there is at least one view on the market (Kindermann 2019) that treats sentences containing predicates of taste (which paradigmatically exhibit the intuition of disagreement) as expressing (multi-) centered contents. So, Worsnip’s view excludes a clear case of disagreement, thus running contrary to (accepted) intuition.

Second, Worsnip’s notion makes no mention of levels of discourse where disagreement takes place. One consequence of this is the possibility of misplacing disagreement. As I mentioned in section 2, several of the contextualist strategies to fend off the challenge from disagreement appeal to pragmatic factors. For example, according to a view like Zakkou’s (2019), when Lisa argues with Bart about licorice, her use of ‘tasty’ triggers a presupposition of superiority to the effect that Lisa’s taste is superior to Bart’s. According to Worsnip’s account, for Lisa and Bart to disagree, they should have attitudes towards contents that neither of them could have compatible attitudes towards. But it is really important that these incompatible attitudes are towards presuppositions, and not towards the semantic content; it wouldn’t do, for example, to take the inconsistency to be between Lisa’s beliefs that licorice is tasty and that Bart’s taste is superior to hers (because, as such, these beliefs are not inconsistent). What this shows is that the level at which disagreement arises needs to be made explicit. This might be very easy to fix, but it requires a fix nevertheless. In contrast, (MD) has the level of discourse build-in in one of the clauses.

It might be argued that, with enough ingenuity, the context could be manipulated in such a way that the exchange elicits the intuition of disagreement: for example, if both Lisa and Bart speak in code, or if enough information regarding the linguistic behavior of the interlocutors is packed in etc. As far as I can tell, this is not problematic for my proposal: if an exchange can be made to elicit the notion of disagreement by manipulating the context in such ways, then that means that there will be conflicting attitudes towards the same content at a certain level of discourse, which is what (MD) predicts. Whether this can be done for any exchange is an empirical matter, one that the proponent of (MD) needs not commit to. It is also worth noting that some issues in this vicinity could perhaps be solved by making (MD) sensitive to context (by claiming, for example, that two interlocutors minimally disagree in a context if such and such conditions apply).

See also Jenkins (2014), who takes the same line regarding verbal disputes in metaphysics.

This is meant to exclude both cases in which one doesn’t accept a proposition because they haven’t considered it or don’t entertain it anymore, where I don’t think any disagreement is present. Other cognitive attitudes, like imagining, assuming, conjecturing etc., which assume entertaining a proposition, don’t seem to be in tension with acceptance of that proposition either, so the issue of disagreement involving those, on one hand, and ACCEPT, on the other, doesn’t arise.

Another problematic case might come from taking doxasic attitudes to be credences, rather than full-fledged beliefs. Thus, if Lisa has credence 0.6 in a proposition while Bart has credence 0.9 in the same proposition, they disagree. Yet, this disagreement doesn’t involve conflicting attitudes (they are both beliefs, albeit of different degrees). I don’t pretend to have a worked out answer here, but here’s a thought: different degrees of belief count as different attitudes. Thus, Lisa’s attitude is of the type CREDENCE 0.6, which is in conflict with the attitude-type CREDENCE NON-0.6 that comprises all credences different from 0.6, including Bart’s attitude of type CREDENCE 0.9 (with the same proviso as before, that CREDENCE NON-0.6 is not a sui-generis attitude, lending itself to various ways of being fleshed out). This being said, I’m happy to concede that more work needs to be done to adapt the model of disagreement proposed here to disagreement in credence.

References

Baghramian, M. & Coliva, A. (2020). Relativism. Routledge.

Baker, C. (2014). The role of disagreement in semantic theory. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 92, 37–54.

Belleri, D. (2014). Disagreement and dispute. Philosophia, 42, 289–307.

Belleri, D., & Palmira, M. (2013). Towards a unified notion of disagreement. Grazer Philosophische Studien, 88, 124–139.

Brogaard, B. (2012). Transient truths. An essay in the metaphysics of propositions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buekens, F. (2011). Faultless disagreement, assertions and the affective-expressive dimension of judgments of taste. Philosophia, 39, 637–655.

Cappelen, H. & Hawthorne, J. (2009). Relativism and monadic truth. Oxford University Press.

Clapp, L. (2015). A non-alethic approach to faultless disagreement. Dialectica, 69(4), 517–550.

Coliva, A., & Moruzzi, S. (2014). Basic disagreement, basic Contextualism and basic relativism (pp. 537–554). XXVI: Iride.

Ferrari, F. (n.d.). Disagreeing with the agnostic. Unpublished manuscript.

Finlay, S. (2005). Value and implicature. Philosophers’ Imprint, 5(4), 1–20.

Finlay, S. (2017). Disagreement lost and found. In R. Shaffer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in Metaethics, volume 12 (pp. 187–205). Oxford University Press.

Gibbard, A. (2003). Thinking how to live. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Glanzberg, M. (2007). Context, content, and relativism. Philosophical Studies, 136, 1–29.

Gutzmann, D. (2016). If Expressivism is fun, go for it!. In C. Meier & J. van Wijnbergen-Huitink (Eds.), Subjective Meaning: Alternatives to Relativism (pp. 21–46). Mouton de Gruyter.

Huvenes, T. T. (2012). Varieties of disagreement and predicates of taste. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 90, 167–181.

Huvenes, T. T. (2014). Disagreement without error. Erkenntnis, 79(supplement 1), 143–154.

Jenkins, C. (2014). Merely Verbal Disputes. Erkenntnis, 79(supplement 1), 11–30.

Kaplan, D. (1989). Demonstratives. In J. Almog, J. Perry & H. Wettstein (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan (pp. 481–563). Oxford University Press.

Kindermann, D. (2019). Coordinating perspectives: De se and taste attitudes in communication. Inquiry, 62(8), 912–955.

King, J. (2007). The nature and structure of content. Oxford University Press.

Kinzel, K., & Kusch, M. (2018). De-idealizing Disagreement, Rethinking Relativism. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 26(1), 40–71.

Kölbel, M. (2004a). Faultless disagreement. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 104, 53–73.

Kölbel, M. (2004b). Indexical relativism vs. Genuine Relativism. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 12, 297–313.

Kölbel, M. (2007). How to spell out genuine relativism and how to defend indexical relativism. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 15, 281–288.

Lasersohn, P. (2005). Context dependence, disagreement, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy, 28, 643–686.

Lasersohn, P. (2016). Subjectivity and perspective in truth-theoretic semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

López de Sa, D. (2007). The many relativisms and the question of disagreement. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 15, 339–348.

López de Sa, D. (2008). Presuppositions of commonality: An indexical relativist account of disagreement. In M. García-Carpintero & M. Kölbel (Eds.), Relative Truth (pp. 297–310). Oxford University Press.

López de Sa, D. (2015). Expressing Disagreement. A Presuppositional Indexical Contextualist Relativist Account. Erkenntnis, 80(supplement), 153–165.

Ludlow, P. (2014). Living words. Meaning Underdetermination and the dynamic lexicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2007). Relativism and disagreement. Philosophical Studies, 132, 17–31.

MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment sensitivity: Relative truth and its applications. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marques, T. (2014). Doxastic Disagreement. Erkenntnis, 79(supplement 1), 121–142.

Marques, T. (2015). Disagreeing in context. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–12.

Marques, T. (2016). Aesthetic predicates: A hybrid dispositional account. Inquiry, 59, 723–751.

Marques, T., & García-Carpintero, M. (2014). Disagreement about taste: Commonality presuppositions and coordination. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 92(4), 701–723.

Moltmann, F. (2010). Relative truth and the first person. Philosophical Studies, 150(2), 187–220.

Parsons, J. (2013). Presupposition, disagreement, and predicates of taste. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 113, 163–173.

Plunkett, D. (2015). Which concepts should we use? Metalinguistic negotiations and the methodology of philosophy. Inquiry, 58, 828–874.

Plunkett, D., & Sundell, T. (2013). Disagreement and the semantics of normative and evaluative terms. Philosophers’ Imprint, 13, 1–37.

Recanati, F. (2007). Perspectival thought. A Plea for moderate relativism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2011). Perspective in taste predicates and epistemic modals. In B. Weatherson& A. Egan (Eds.), Epistemic Modality (pp. 179–226). Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2012). Necessitarian propositions. Synthese, 189(1), 119–162.

Schaffer, J. (2018). Confessions of a schmentencite: Towards an explicit semantics. Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2018.1491326.

Schroeder, M. (2008). Being for. Evaluating the semantic program of Expressivism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sennet, A. (2016). Ambiguity. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/ambiguity/. Accessed 18 Feb 2020.

Silk, A. (2016). Discourse Contextualism. A framework for Contextualist semantics and pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stevenson, C. L. (1963). The nature of ethical disagreement. In C. L. Stevenson (Ed.), Facts and Values: Studies in Ethical Analysis (pp. 1–9). New Haven: Yale University press.

Stojanovic, I. (2007). Talking about taste: Disagreement, implicit arguments, and relative truth. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30, 691–706.

Stojanovic, I. (2012). Emotional disagreement. Dialogue, 51(1), 99–117.

Sundell, T. (2011). Disagreements about taste. Philosophical Studies, 155, 267–288.

Worsnip, A. (2019). Disagreement as interpersonal incoherence. Res Philosophica, 96(2), 245–268.

Wyatt, J. (2018). Absolutely tasty: An examination of predicates of personal taste and faultless disagreement. Inquiry, 61(3), 252–280.

Zakkou, J. (2019). Faultless disagreement: A defense of Contextualism in the realm of personal taste. Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann.

Zeman, D. (2017). Contextualist answers to the challenge from disagreement. Phenomenology and Mind, 12, 62–73.

Zeman, D. (2020). Faultless disagreement. In M. Kusch (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Relativism (pp. 486–495). London: Routledge.

Zouhar, M. (2018). Conversations about taste, Contextualism and non-doxastic attitudes. Philosophical Papers, 47(3), 429–460.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Delia Belleri, Adrian Briciu, Alex Davies, Alexander Dinges, Filippo Ferrari, Daniela Glavaničová, Sanna Hirvonen, Mihai Hîncu, Miloš Kosterec, Max Kölbel, Martin Kusch, Victoria Lavorerio, Carlos Nuñez, Naomi Osorio-Kupferblum, Miguel Angel Sebastian, Katharina Sodoma, Martin Vacek and Julia Zakkou, who have provided valuable feedback (some of them to more than one version of the paper). I would also like to thank the audiences at the The Emergence of Relativism project seminar, University of Vienna, 19.01.2018 and ALFAn 5-PHILOGICA 5 conference, Villa de Leyva, 16-18.05.2018. Many thanks to a reviewer for this journal for their insightful comments and encouragement. The research pertaining to this paper has been funded by a Lise Meinter grant from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): project number M2226-G24.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zeman, D. Minimal Disagreement. Philosophia 48, 1649–1670 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-020-00184-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-020-00184-8