Abstract

Using a conviction-based measure, we find that local (state-level) public corruption exerts a negative effect on the lending activity of US banks. Our baseline estimations show that the difference in public corruption between, for example, Alabama, where corruption is high, and Minnesota, where corruption is low, implies that banks headquartered in the former state grant 0.55% less credit (or $3.52 million for the average bank) ceteris paribus. Using proxies for relationship lending and monitoring, we also find that these bank characteristics weaken the negative effect of public corruption on lending. These results are robust to tests that address endogeneity, to the use of perception-based measures of corruption, and after controlling for credit demand conditions. In further analysis, we show that these effects are more evident for smaller banks and banks operating in a single state. These findings provide evidence that public corruption could facilitate information asymmetry in the lending market and, thus, could hinder local development by reducing bank credit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Does public corruption hinder bank lending activity? Can bank managers adopt strategies to diminish the impact, if any, of public corruption on bank lending? If yes, then what are these strategies? Answering these questions could be of importance for policymakers, banks, corporations, and citizens alike. Bank credit is crucially relevant for economic growth (De Gregorio and Guidotti 1995; Jayaratne and Strahan 1996), corporate development (Beck et al. 2008; Amore et al. 2013; Campello and Larrain 2015) and consequently for employment.

The extant literature provides grounds for the conjecture that public corruption could discourage banks from granting credit. Several studies associate public corruption with a deterioration of firm transparency and performance (Fisman and Svensson 2007; Dass et al. 2016; Zeume 2017; Brown et al. 2019). Less transparent borrowers induce information asymmetry in the lending market while weaker firm performance, and hence a weaker ability to repay loans, increases the riskiness of the borrower pool.

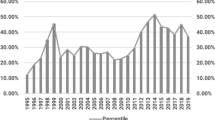

Despite the above, studies that focus on the effects of local public corruption on bank lending are scarce and we aim to fill this gap in the literature. The US is an ideal testing ground to examine the relationship between public corruption and lending. Bank funding is important for US firms as it represents the majority of new corporate financing (Bharath et al. 2008; Hasan et al. 2014). Next, even though the deregulation of the US banking industry decreased and eventually eliminated, through the Riegle-Neal Act of 1994, the barriers to interstate banking, the largest parts of the business of US banks remain at their headquarter state (Deng and Elysiani 2008; Goetz et al. 2016). Hence, local public corruption could be relevant for bank credit decisions across states. The US setting also allows us to segregate the effect of public corruption on bank lending given the relatively similar socioeconomic and regulatory frameworks across states. Further, in a US-focused study, we can use objective measures of public corruption that are based on corruption-related crime convictions and represent the ‘actual’ level of corruption to a large extent. Lastly, the US exhibits a significant cross-state variation in public corruption (Glaeser and Saks 2006). This alleviates concerns about public corruption being less of an issue in the US because of its advanced country status. A comparison of Fig. 1 with Fig. 2 shows an inverse relationship between corruption conviction rates and loans to assets ratios across the US states, and it motivates a systematic analysis of the relationship between the two.

Using both quarterly and yearly data on US commercial banks for the 1995–2013 period we show that public corruption decreases bank lending activity. This effect is both statistically and economically significant. As an illustration, the difference in public corruption between Alabama, where corruption is high, and Minnesota, where corruption is low, is roughly equivalent to one standard deviation. Our result implies that banks in Alabama grant 0.55% less credit (or $3.52 million for the average bank) than banks in Minnesota ceteris paribus. Taking into account that several banks are headquartered in each US state, these findings denote that public corruption hampers access to bank credit and, thus, could hamper local economic development.

We carry out three exercises that show that supply-side considerations of banks facilitate the negative relationship between public corruption and lending. The first is the inclusion in the models of state-level variables that help to control for credit demand. These comprise the state unemployment rate, the income per capita and particularly the state coincident index that reflects the general level of the state economic conditions in a single statistic. We also find that banks with lower quality loan portfolios are more hesitant to grant credit when public corruption is high. In this respect, we show that bank characteristics impact the effect of local public corruption on lending activity supporting that supply-side considerations drive our findings to a large extent. Finally, we show that public corruption makes banks more reluctant to grant commercial and real estate loans, which are more sensitive to local public corruption, in comparison with loans to individuals and agriculture loans.

Our analysis also suggests that certain bank characteristics, which reflect strategies that banks adopt in order to overcome information asymmetry issues, moderate the negative relationship between public corruption and lending activity. Using established proxies for relationship lending and bank monitoring effort we show that these two bank characteristics weaken the negative association between local public corruption and lending activity.

We perform several robustness checks to support our main findings. Our results are robust to tests that address endogeneity, to different measures of public corruption, and to alternative clustering of the standard errors. We also perform further analysis to enrich our results. We show that the negative effect of local public corruption on lending is more pronounced for smaller banks. This finding is consistent with the conjecture that smaller banks are more likely to lend locally. We also find that the negative effect of local public corruption on lending holds in both the pre-deregulation (i.e., pre-1994) and the post-deregulation periods (i.e., post-1994), while it is more evident for banks that operate in a single state.

This study adds to the extant literature in several ways. A wide stream of the literature investigates the drivers of lending activity because of the importance of bank credit for economic growth. Most of this research focusses on the effect of macro-factors, such as monetary policy, and bank regulation on bank lending (e.g., Thakor 1996; Gambacorta and Mistrulli 2004; Jiménez et al. 2012; Delis et al. 2014; Acharya et al. 2018). However, studies that associate local institutional quality with bank lending are scarcer. We contribute to this literature by showing that local public corruption exerts a negative and significant effect on lending activity. We also show that this effect relates to credit supply considerations and not merely to credit demand. These findings show that public corruption is a source of information asymmetry in the local credit markets that discourages banks from providing credit.

In this way, we contribute to the more specialized stream of the banking literature that examines corruption-related issues in bank lending (Beck et al. 2006; Barth et al. 2009; Houston et al. 2011; Weill 2011; El Ghoul et al. 2016; Wellalage et al. 2018). Most of these studies focus on how integrity in bank lending (i.e., loan officer bribery) affects the probability that firms will obtain loans in a cross-country context or focus on emerging economies. We complement these studies by showing that public corruption is also a factor that adversely affects the provision of bank credit even in the context of very advanced economies, such as in our case, the US, where institutional quality issues are considered less prevalent.

Furthermore, we provide evidence that proxies for relationship lending and monitoring weaken the negative relationship between public corruption and lending activity. Hence, we add to the studies which find that placing emphasis on borrower monitoring and on the acquisition of “soft” information on borrowers assists banks in overcoming information asymmetry issues (Sufi 2007; Kysucky and Norden 2015; López-Espinosa et al. 2017). Our findings corroborate the view in the context of information asymmetry stemming from local public corruption.

Finally, we add to the growing stream of US-focused research that explores the effects of local public corruption on firm-level outcomes (e.g., Dass et al. 2016; Smith 2016; Parsons et al. 2018; Brown et al. 2019). These studies find that local public corruption decreases firm transparency and value while it also induces unethical corporate behavior. Since these effects could aggravate the information asymmetry concerns of lenders, our study is a sensible extension of this literature. We show that the negative effects of US public corruption spill over to the credit market and from this standpoint could also restrict local economic development.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. First, we present our theoretical predictions and hypotheses. Second, we describe our data and methodology. Next, we present our key findings and main robustness checks. Following, we provide a summary of some additional robustness tests and further analysis. The final section concludes.

Theoretical Considerations and Hypotheses Development

The Effect of Local Public Corruption on Bank Lending Activity

Local public corruption could negatively affect lending activity by increasing the information asymmetry between local borrowers and local banks. Shleifer and Vishny (1993) posit that a characteristic of corruption is its illegality and, consequently, its secrecy. Firms in areas with high local public corruption could adopt more secrecy that would render them less informationally transparent. This may suggest a defensive move stemming from managers’ willingness to protect the firms’ assets from the expropriation instincts of public officials. It could also represent managers’ efforts to conceal their potential participation in corruption-related activities from investors. Some empirical studies show that US firms located in areas with a high level of public corruption are less transparent. Dass et al. (2016) find that firms in US states with higher levels of local public corruption exhibit lower informational transparency as measured by higher earnings manipulation and provision of less managerial guidance about their earnings. Dass et al. (2018) and Xu et al. (2019) find similar results.

Another potential reason for a corruption-induced increase in information asymmetries is the creation of a local culture of corruption that could legitimize unethical behavior. The literature of the economics of corruption shows that local public corruption increases the propensity of the local population to engage in corrupt and unethical behavior (Hauk and Saez-Marti 2002; Fisman and Miguel 2007; Barr and Serra 2010). Fisman and Miguel (2007), for example, show that individuals originating from areas with high corruption are more likely to violate laws and regulations. This local culture could also pervade local firms (Schneider 1988). Parsons et al. (2018) provide evidence that local corporate misconduct is positively associated with the level of local public corruption in the US. In another study, Liu (2016) shows that firms that employ staff who originate from high corruption areas as key insiders are more likely to engage in accounting fraud. Other studies provide similar evidence regarding tax evasion and securities fraud litigation (Alon and Hageman 2013; DeBacker et al. 2015; Dass et al. 2018). The above discussion suggests that banks located in areas with higher levels of local public corruption could face a less transparent pool of borrowers.

Local public corruption could also increase the information asymmetry banks face due to the higher uncertainty regarding the cash-flows, and thus the ability to repay loans, of local firms. Empirical evidence from international studies shows that firms operating in areas with more corruption exhibit lower firm value, growth and profitability because of higher operating costs, lower efficiency and expropriation risk (Fisman and Svensson 2007; Durnev and Fauver 2011; Healy and Serafeim 2015; Lin et al. 2016; Van Vu et al. 2018). Smith (2016) shows that even US firms face local corruption-induced risks, such as expropriation risk. Brown et al. (2019) provide recent US-based evidence that local public corruption exerts a negative effect on firm value.

Based on the above arguments, we conjecture that banks in areas (states) that exhibit a higher level of local public corruption would be more reluctant to grant credit. Thus, we formulate our main hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis1 (H1)

Local public corruption could have a negative effect on the lending activity of banks in the US states.

The Mediating Role of Relationship-Based Lending and Monitoring Effort on the Relationship Between Local Public Corruption and Bank Lending Activity

The Mediating Role of Relationship-Based Lending

In terms of their lending activity banks could rely more on transaction-based or relationship-based technologies. Transaction-based lending technologies employ ‘hard’ information on borrowers. This includes the borrowers’ accounting and financial statement information, the quality of their collateral, and the use of the former as inputs in credit-scoring models. However, as we explain in the development of hypothesis H1, local public corruption could decrease the financial transparency of the local borrowers and the quality of their financial information. This, in turn, could raise doubts regarding the soundness of this type of information and its value to the transaction lender. On the other hand, relationship-based lending technologies depend on the collection and processing of ‘soft’ proprietary information on borrowers. Such ‘soft’ information comprises information that is not easily quantifiable such as the borrower’s character and reliability (Berger and Black 2011). Banks source ‘soft’ information on borrowers mostly through their numerous contacts with them and through contacts with other parties of the local community such as suppliers and clients. Notably, ‘soft’ information might be more difficult to obtain than ‘hard’ financial statement data, but the former is of great value to the lender when they deal with borrowers of lower ‘hard’ informational transparency. Considering that local public corruption could exacerbate information asymmetries, relationships between lenders and borrowers that generate ‘soft’ information could be of importance in decisions regarding credit provision.

Additionally, the literature suggests that small banks use ‘soft’ information more intensively than larger institutions do since the former exhibit less complex organizational structures that allow the easier transmission of this type of information (Berger and Udell 2002; Liberti 2018). Smaller banks use a so-called ‘character approach’ in their credit decision making. This ‘character approach’ is based on non-financial characteristics stemming from personal interactions with loan applicants (Cole et al. 2004). Given that our sample includes the total of US commercial banks, the majority of which are relatively small banks, the use of relationship-based lending technologies that rely on ‘soft’ information could mitigate concerns regarding the information asymmetry that local public corruption could induce.

To proxy for relationship-based lending, we use the ratio of its core deposits (i.e., transaction and saving deposits) to total assets. Banks use core deposits to fund informationally opaque relationship loans given that their elasticity about interest rates is low which makes them an appropriate source of funding for illiquid relationship loans (Chiorazzo et al. 2018). Banks could use core deposits to finance these types of loans given that they are more difficult to be withdrawn as banks provide these depositors with additional transaction and consulting services. Also, core deposits are largely insured and thus more stable compared to demand deposits (Drechsler et al. 2017). Thus, core deposits provide a stable route through which banks could build bank-depositor relationships that might lead to increased purchases of financial products (i.e., loans) made by depositors (DeYoung and Rice 2004; Chiorazzo et al. 2018). Several studies lend support to the notion that core deposits and relationship-based lending are closely associated (Berger and Uddel 1995; Qi 1998; Berlin and Mester 1999) while other research shows that banks with a high level of core deposits specialize in more information-intensive loans (Black et al. 2007, 2010). Following the preceding discussion, we formulate our second hypothesis (H2):

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

Banks that engage in more relationship-based lending could be less affected in terms of lending activity by the adverse effects of local public corruption.

The Mediating Role of the Monitoring Effort

Strong monitoring effort is another bank feature that could attenuate the potential adverse effects of local public corruption on lending activity. Bank monitoring has long been the subject of previous research because banks benefit from economies of scale in monitoring and access to private information on borrowers (Diamond 1984; Fama 1985). Besanko and Kanatas (1993) show that banks are special because they provide loans in combination with monitoring services. Bank monitoring effort could have several positive effects such as the increase in the chance of success of the borrowers’ projects (Boot and Thakor 2000; Allen et al. 2011). A positive effect of a strong bank monitoring effort that is very relevant to this study is that it could play a governance role that could decrease the information asymmetry between banks and borrowers (Shleifer and Vishny 1997). For example, Ahn and Choi (2009) show that bank monitoring decreases the propensity of firms to engage in earnings manipulation. Therefore, strong monitoring could weaken the potential decrease in the quality of the borrowers’ financial information that local corruption could encourage. In addition, Saunders and Song (2018) find that a strong bank monitoring effort exerts a chilling effect on the risk-taking behavior of borrowers. This could stem from the disciplining role of the negative consequences that lenders could impose on borrowers in case of violation of the loan contract terms. Such consequences comprise the redundancy of managers and the decline of further financing requests (see, for example, Roberts and Sufi (2009) and Ozelge and Saunders (2012). Thus, a strong monitoring effort could attenuate the potential that borrowers would engage in risky, unethical behavior, such as corporate misconduct and accounting fraud, which could stem from a local culture of corruption.

To proxy for monitoring effort, we employ the salary expenses to total non-interest expenses ratio of each bank. As monitoring effort is primarily human-oriented, and to the extent that salaries represent the capacity of employees in monitoring operations, then this ratio could gauge the level of monitoring resources and the expertise of these staff (Coleman et al. 2006; Lee and Sharpe 2009; Bhat and Desai 2017). In more detail, Coleman et al. (2006) suggest that the two main assumptions that offer credence to this proxy of monitoring are that the loan officers with strong monitoring expertise attract higher salaries and that the number of employees is readily related to the quantity of loan monitoring. Following the discussion above, we formulate the following hypothesis (H3):

Hypothesis 3 (H3)

Banks that engage in stronger monitoring could be less affected in terms of lending activity by the adverse effects of local public corruption.

Data, Research Design, and Descriptive Statistics

Sample

We obtain bank data from the bank regulatory database of WRDS. This database comprises quarterly accounting and headquarters location information for US banks via the Call & Thrifts financial reports. Further, we retain, following previous studies, bank-quarter observations where assets, loans, and capital have positive values. This process yields a final sample of 875,867 quarterly observations from 14,762 banks from 1985 to 2013. Note that the number of observations declines in the estimations because we use lagged values of the bank-specific control variables and sometimes it also depends on the type of the robustness test we perform to support our main analysis. Table 1 reports the definitions, measurement details, and sources of the main variables we use in the regression analysis.

Measures of Local Public Corruption

We measure local public corruption with the yearly number of corruption-related convictions across the US states from 1985 to 2013. We normalize the number of these convictions by each state’s population (i.e., by 100,000 inhabitants for each state). This measure of public corruption has been used extensively in the literature (see, for example, Glaeser and Saks 2006; Campante and Do 2014; Smith 2016). We source the corruption data from the Public Integrity Section (PIN) Reports of the US Department of Justice (DoJ). The convictions in the PIN reports focus on crimes that involve the abuse of public trust by government officials and employees such as cases of bribery, fraud, political-contribution abuse, and illegal conflicts of interest.

The use of corruption-related convictions as a measure of public corruption exhibits some important advantages. Firstly, the conviction measure is more objective in comparison with the perception-based corruption measures that cross-country studies usually employ (Glaeser and Saks 2006). Criticisms about the perception-based measures point to their lack of objectivity, short time frame, and the low survey response rate. Secondly, the conviction measure could compare the level of public corruption across states efficiently as it only applies to the US. This reduces issues arising from confounding factors such as the cultural and institutional differences that the cross-country measures may have (Fisman and Gatti 2002; Smith 2016). Furthermore, because federal authorities and the federal justice system handle the cases of public corruption, one can assume a moderate homogeneity of enforcement (Glaeser and Saks 2006; Smith 2016) that enhances comparability. Thirdly, the corruption-related convictions involve both notable cases of corrupted officials holding offices at the highest level of government but also lesser-known public corruption cases of local government employees. Hence, this measure could capture the variation of the culture of corruption at the local (i.e., state) level adequately.

Despite the advantages of the conviction-based measure of public corruption, Goel and Nelson (2011) suggest that it represents the level of uncovered corruption. Hence, it may not show a portion of public corruption that the perception-based indices could capture. Therefore, in robustness tests, we also use three perception-based measures of state-level public corruption. These are the illegal corruption perception-based index for the US states by Dincer and Johnston (2015), the “State Integrity Index” developed by the Center of Public Integrity, and the corruption perception index of Boylan and Long (2003). We provide details on these three perception-based corruption measures in Table 1.

Regression Specification

We test our main hypothesis, H1, using the following empirical model:

where \(i,s, t\) denote the bank, the state and time, respectively. To capture \(Bank\;lending\;activity _{i,s,t}\) we employ the natural log of the value of total loans (Rodnyansky and Darmouni 2017; Acharya et al. 2018; Cheng et al. 2018).Footnote 1 We also provide estimations that use the total loans deflated by total assets as a second measure of lending activity. The measure of local public corruption, \(State\;corruption_{s,t}\), stands for the rate of corruption-related convictions per hundred thousand (100,000) inhabitants in states, as per Smith (2016). Further, we use the contemporaneous value of the local public corruption measure because the conviction data have an inherent lag from the corruption-related crime (Smith 2016). The vector \(Bank\;controls_{i,s,t - 1}\) comprises bank-specific control variables such as bank size, return on assets, liquidity, and capitalization. We use the lagged values for the bank controls in order to attenuate simultaneity issues. Further, the vector \(State\;controls_{s,t}\) includes state-level characteristics that control for personal income, unemployment, and population. The use of these state controls is important because they can affect bank lending activity and also may correlate with local public corruption (Glaeser and Saks 2006; Smith 2016). Lastly, we saturate the model with bank, state, and time fixed effects, \(\mu_{i}\), \(\omega_{s} ,\) and \(\tau_{t} ,\) respectively (DeYoung et al. 2018; Agarwal et al. 2019). We provide the summary statistics of the variables, the median values of public corruption by state, and the correlation matrix in Tables 2, 3 and 4 respectively.

To test our secondary hypothesis, H2, we augment model (1) above as:

where \(\beta_{4}\) is the coefficient of interest. This is the coefficient of the interaction between local public corruption and the core deposits to total assets ratio (COR DEP/TA i,s, t−1), which is the proxy for relationship-based lending. We conjecture that this variable could mediate the relationship between local public corruption and bank lending activity and we expect this coefficient to be positive. Similarly, to test for H3, we augment our model (1) and estimate

where the salary expenses to total non-interest expenses (SAL EX/TE i,s,t−1) is the proxy for bank monitoring effort. Because we expect that higher monitoring reduces, on average, the negative impact of corruption upon bank lending activity, we expect this interaction to have a positive sign.

As for the frequency of the data, t, in our main analysis, we report results by using both quarterly and annual data. There are several reasons for the choice of using quarterly data. The first is that the original frequency of the data in Call reports is quarterly, and much of the research focussing on US bank lending tends to use quarterly data (e.g., Delis et al. 2014; Kim and Sohn 2017; Acharya et al. 2018). Secondly, bank managers take into account the quarterly economic conditions and bank balance sheet characteristics when they decide to grant lending (Delis et al. 2014). This is rational since bank lending decisions usually have a small time frame. Agarwal and Ben-David (2018), for example, show that the time interval between a loan application and a decision to grant credit is less than 2 months. Thirdly, two of our hypotheses (H2 and H3 as specified in Eqs. (2) and (3) respectively) involve interactions between the public corruption measure that exhibits yearly variation and the bank characteristics, which display quarterly variation. These interaction terms then also display quarterly variation. Therefore, the use of quarterly data increases estimation efficiency due to the higher number of observations. Furthermore, the higher frequency of the two bank-specific characteristics helps to reduce the potential collinearity between the three regressors—i.e., each of the two bank-specific characteristics, state corruption, and their interaction. Hence, for each quarter in a year, we assign the yearly state-specific corruption.Footnote 2

We, however, take into account that local public corruption exhibits yearly variation by state and we also provide results from estimations that use yearly data. To this end, we use yearly measures based on the 4th quarter of each year as in Berger and Udell (2004). The authors indeed argue that this quarter call is generally considered the most accurate as it smooths out short-term fluctuations in lending.Footnote 3

Main Results

Baseline Results

Table 5 depicts the findings from the baseline estimations. Panel A reports results from models that use quarterly data, while the estimations in Panel B use yearly frequency data. The first three models of Panel A and Panel B of Table 5 use the natural log of total loans as the lending activity variable, while in the fourth model of each panel we employ the total loans deflated by total assets. All the models of Table 5 are saturated with bank, state, and time (year-quarter in Panel A and year in Panel B) fixed effects.

Regarding the estimations that use quarterly data, we start with a simple regression of local public corruption on the lending activity variable (Ln Loans) in model 1 of Panel A of Table 5. The result shows that local public corruption has a negative and significant association with lending activity at the 1% level. In model 2 of Panel A of Table 5, we extend the specification of model 1 with the addition of the lagged bank-level controls. The findings from this model still indicate a negative and significant association of local public corruption with bank lending activity at the 1% level. We further extend the specification with the addition of state-level control variables to reach the full model of Eq. (1). The findings from the full specification are available in model 3 of Panel A of Table 5. The results indicate that local public corruption retains a negative and significant association with bank lending activity at the 1% level after controlling for bank-level and state-level characteristics. Overall, these findings are consistent with hypothesis H1, which predicts that banks located in states with a higher level of public corruption would reduce lending activity. We obtain similar results in model 4 of Panel A of Table 5 when we use the total loans deflated by total assets (TL/TA) as the lending activity variable. The findings we obtain from the analogous models that use yearly frequency data are also similar (see all models of Panel B of Table 5).

To infer the economic significance of our results, we use the difference between a bank with headquarters in Alabama, where public corruption is high (i.e., 0.409; see mean value of Table 3), and a bank in Minnesota, where public corruption is low (i.e., 0.148; see mean value of Table 3). The difference between the two states (0.261) is comparable to a one standard deviation (0.252) increase in STATE COR (see Table 5). By employing the coefficient in model 3 of Panel A of Table 2, we find that a bank in Alabama grants 0.55% less credit ((e(0.0211 × 0.261) − 1) × 100) than a bank in Minnesota, ceteris paribus. The average bank in the sample grants around $637 million (e(11.062)) of credit. Hence, this means a decrease in granted credit by $3.52 million ($3.52 = 0.55% × $637) for the average bank. This is an economically important effect in terms of the local credit supply, particularly if one considers that each state has several banks that tend to lend locally. Hence, these results provide evidence that local public corruption could obstruct local economic development by decreasing credit availability.

Regarding the control variables, the results are generally consistent across the models of Panel A and Panel B of Table 5. We find that larger banks exhibit stronger lending activity. The effect of the natural log of total assets (SIZE) has a positive and significant effect on lending activity at the 1% level. Profitability, as proxied by the return on assets ratio, is found to exert a positive and significant effect on bank lending at the 1% level in models 2–4 of Panel B of Table 5. This finding is consistent with the view that higher profits induce banks to increase credit supply. We also find that banks with higher equity to assets ratio (E/TA) display weaker lending activity. In the majority of the models of Table 2, the effect of the equity to assets (E/TA) on lending activity is negative and significant at the 1% level. These findings denote that equity capital induces banks to be less aggressive in terms of lending. This could imply that when shareholders have more of their money at stake, they monitor banks more closely and bank managers become more cautious in terms of lending activity (Berger and DeYoung 1997). Liquidity, as measured by the cash to total assets ratio (CASH RATIO), also has a negative association with bank lending activity. As far as the state-level controls are concerned, our results show that banks in less rich states exhibit weaker lending activity. The effect of the state-income per capita (INCOME) on bank lending activity is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. Our results also show that the state unemployment rate (UNEMP) displays a negative and significant association with lending activity (see model 3 of Panel A and Panel B of Table 5). Finally, we find that the natural log of the population has a negative association with lending activity. The findings for the control variables are generally consistent with the findings of other studies (see, for example, Rodnyansky and Darmouni 2017; Acharya et al. 2018; Cheng et al. 2018).

Accounting for Loan Demand

The baseline models show a negative and significant association between local public corruption and bank lending activity. In this section, we attempt to discern whether this association stems merely from a decrease in the demand for credit or also because of the lending behavior of banks—i.e., because of credit supply considerations. In the baseline estimations, we have included control variables that could capture, to some extent, the demand for credit at the state level. These are the level of state unemployment and the state-income per capita. We proceed with the inclusion in the baseline model of an additional variable that could capture the demand for loans. This is the coincident index for each state in each year-quarter. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia produces this index and makes it available online.Footnote 4 In a single statistic the index provides the economic conditions for each stateFootnote 5 with higher values denoting better state economic conditions. We conjecture that the coincident index could serve as a proxy for local loan demand. The data on the coincident index are monthly. We take the average for each year-quarter to construct a quarterly coincident index (COIN) to include in the specifications that use quarterly data. The results from these models are available in Panel A of Table 6.

In model 1 of Panel A of Table 6, we find that the coincident index (COIN) has a positive and significant association with the natural log of total loans (Ln Loans). This finding is consistent with the notion that, in times of improved economic conditions, the demand for credit increases. However, we also observe that the association between local public corruption and the log of total loans (Ln Loans) remains negative and significant at the 1% level. Similarly, in model 2 of Panel A of Table 6, which uses the total loans deflated by total assets (TL/TA) as proxy for lending activity, the coefficient on the local public corruption remains negative and significant at the 1% level after controlling for loan demand with the use of the coincident index (COIN). The results are similar in the analogous models 1 and 2 of Panel B of Table 6 that use yearly frequency bank data together with a yearly version of the coincident index (COIN).

Another way to discern whether credit supply considerations play a role in the negative association between local public corruption and lending activity is to use interactions of the corruption variable with bank characteristics (see, for example, Kashyap and Stein 2000; Delis et al. 2014). This strategy is based on the notion that if the negative association between local public corruption and lending is driven solely from the demand for credit, then it should not depend on bank characteristics. On the other hand, if credit supply considerations also drive the negative relationship between corruption and lending activity, then this would be more evident in banks with specific characteristics. This implies that local public corruption induces lending activity to differ between banks with different characteristics. One such characteristic is the quality of a bank’s loan portfolio. We expect that banks with loan portfolios of lower quality would be more hesitant to grant credit when they are located in states with a higher level of local public corruption to avoid a further deterioration of their asset portfolio. To test this prediction, we run specifications that include the interaction term between the local public corruption variable and the ratio of the lagged loan loss provisions to total loans (LLP/TL), which serves as a proxy for the quality of the loan portfolio.

The results from this exercise using quarterly data are available in models 3 and 4 of Panel A of Table 6. In model 3 of Panel A, the interaction between local public corruption (STATE COR) and the loan loss provisions to total loans ratio (LLP/TL) is negative and significant. In addition to this, the individual effect of local public corruption on the log of total loans (Ln Loans) is also negative and significant at the 1% level. The results from model 4 of Panel A that uses the total loans deflated by total assets (TL/TA) as an alternative lending activity variable are similar. These findings show that the negative effect of local public corruption on lending activity strengthens for banks with lower asset quality. We further extend this test with the inclusion of state*year-quarter fixed effects. The inclusion of this type of fixed effects in the models could capture the demand for credit in each state in each quarter. In the presence of state*year-quarter fixed effects, we cannot include state-level variables that exhibit time heterogeneity because they would be perfectly correlated with these fixed effects. Therefore, we drop the state variables such as the local public corruption measure from the specifications. However, in the presence of state*year-quarter fixed effects, the interaction between the loan loss provisions to total loans ratio (LLP/TL) and the local public corruption measure can still be identified. In models 5 and 6 of Panel A, this interaction displays a negative and significant relationship with the lending activity variables. Hence, lending activity declines for banks that have lower loan portfolio quality in states with higher local public corruption. In models 5 and 6 of Panel B of Table 6, we repeat this exercise by using yearly frequency and data and we obtain similar results.

Another way to discern whether supply-side considerations play a role in the negative relationship between local public corruption and lending is to examine different types of loans. Our theoretical arguments (e.g., increase in information asymmetry due to an increase in firm opacity) that banks in areas with higher local public corruption decrease lending activity relate mostly to corporate loans. Hence, we expect that in the presence of high public corruption, banks would be more hesitant to grant commercial and industrial loans because these loans could be particularly vulnerable to the potential adverse effects of local public corruption. Similarly, we expect that real estate loans could also be affected adversely by local public corruption, given that real estate loans also include real estate loans for commercial purposes. On the other hand, we expect the lending activity about other types of loans – such as loans to individuals and agriculture loans—to be less sensitive to local public corruption. The results of this analysis using quarterly data are available in Panel A of Table 7.

In models 1 and 2 of Panel A of Table 7, we find that local public corruption exerts a negative and significant effect at the 1% level on the natural log of commercial and industrial loans and the natural log of the real estate loans respectively. On the contrary, we find a much weaker relationship between local public corruption and bank lending for other types of loans, such as loans to individuals and agriculture loans (see models 3 and 4 of Panel A of Table 7). The results from the models that use yearly frequency data are similar (see all models of Panel B of Table 7). Altogether, the above findings point to the conclusion that the negative association between bank lending and local public corruption also works through the bank supply-side channel.

The Mediating Effect of Relationship-based Lending and Monitoring Effort

Our previous specifications show that local public corruption decreases bank lending. Yet, this effect may vary with bank heterogeneity stemming from the strategies that banks use to overcome corruption-induced information asymmetry issues. Thus, in this section, we test whether banks that use more relationship-based lending and engage in stronger monitoring could attenuate the adverse effect of local public corruption on lending activity (i.e., hypotheses H2 and H3). For this test, we run models that include the interaction term between the ratio of core deposits to total assets (salary expenses to the total non-interest expenses) as a proxy for relationship-based lending (monitoring effort) and the local public corruption variable.

We run models using both quarterly (Panel A) and yearly (Panel B) frequency data. The results from this exercise are available in Tables 8 and 9.

In model 1 of Panel A of Table 8, the results show that the interaction between local public corruption (STATE COR) and the core deposits to total assets (CORE DEP/TA) has a positive and significant effect on the log of total loans (Ln loans) at the 5% level. Further, in model 2 of Panel A of Table 8, we include state*year-quarter fixed effects to account for all the state-level characteristics that vary across time. In this way, we take into account any omitted variable bias stemming from other state characteristics that could correlate with local public corruption as well as loan demand. As a result, we drop all the state-level time-variant variables from the specification, including the corruption variable, as it correlates perfectly with the state*year-quarter fixed effects. However, the model can still identify the interaction between local public corruption (STATE COR) and the core deposits to total assets (CORE DEP/TA) which is positive and significant at the 1% level. We obtain similar results in models 3 and 4 of Panel A of Table 8 when we perform the same analysis using the alternative lending activity proxy as the dependent variable, which is the total loans deflated by total assets (TL/TA).

Turning now to our findings using yearly bank-level data in Panel B of Tables 8, we observe that the interaction between local public corruption (STATE COR) and the core deposits to total assets (CORE DEP/TA) is positive and significant at the 1% level in the models that use the ratio of total loans over total assets as dependent variable (see models 3 and 4 of Panel B of Table 8). Overall, these findings lend support to the H2 hypothesis, suggesting that banks that rely more on relationship-based lending could be affected less by the adverse effects of local public corruption, in terms of lending activity.

Further, in Table 9, we provide the results from the models that test the mediating effect of monitoring effort on bank lending activity. The findings from both the quarterly and yearly specifications (see models 1–4 of Panel A and Panel B of Table 9, respectively) are in line with hypothesis H3, which posits that monitoring effort could weaken the adverse effects of local public corruption on bank lending activity. The interaction between local public corruption (STATE COR) and the monitoring effort proxy (SAL EX/TE) is positive and significant at least at the 5% level in all models.

Overall, these findings provide empirical support to hypotheses H2 and H3, as we find that banks that engage in more relationship-based lending and in stronger monitoring effort could increase their lending activity when local public corruption is high. As for the rest of our explanatory variables, the results are in line with those of our baseline regressions.

Main Robustness Analysis

Addressing Endogeneity

One of the challenges of our identification strategy is the potential endogeneity between bank lending activity and local public corruption. Endogeneity may be present for a number of reasons. The first is the potential for a feedback effect (i.e., reverse causality) from bank lending activity upon local public corruption. Access to credit could influence the propensity of local economic and political agents to participate in corruption-related activities. For example, bank credit may increase competition in the business sectors (Black and Strahan 2002) and, thus, reduce the rents of local firms. This could reduce the rewards from corruption and, consequently, the inclination of public officials to engage in corruption (Ades and Di Tella 1999). Moreover, Jha (2018) provides cross-country evidence that more autonomy conferred to banks regarding lending decisions and lower entry barriers in the bank industry reduces corruption. This could be relevant in the US context because our sample encompasses the period after the Riegle-Neal Act of 1994 that led to the abolishment of restrictions on interstate banking and branching. The second potential endogeneity concern is that of a potential omitted variable bias; Jha (2018) for instance shows that banking supervision has a negative association with corruption. Hence, bank supervision could relate to both lending and corruption. Despite the fact that US commercial banks need to abide by the same regulations, nationally-chartered commercial banks are subject to supervision solely by federal regulators while state-chartered commercial banks are subject to the same by both federal and state supervisors.Footnote 6 Agarwal et al. (2014) show that state supervisors are more lenient than their federal counterparts are in the enforcement of bank regulations. Thus, some heterogeneity in terms of bank supervision could be present in our sample.Footnote 7

To address the above endogeneity concerns, we employ a two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental variable (IV) framework. To this aim, we need to find an appropriate instrument for local public corruption. In studying the role of corruption on the firm financial policy, Smith (2016) builds upon Campante and Do (2014), who show that isolated state-capital cities exhibit a positive association with public corruption in the US states. The theoretical rationale is that state-capital isolation decreases the accountability of public officials (Wilson 1966; Maxwell and Winters 2005). Campante and Do (2014) provide empirical evidence of the accountability-related channels through which state-capital isolation induces public corruption. They show that local media coverage of state politics is lower when their readership is not concentrated around the state-capital. They also find that the further away individuals live from the state-capital, the less informed and interested they are in state politics and less likely to vote in state elections. Consequently, lower accountability of public officials enhances their opportunities and incentives to misuse the public office for private gain.Footnote 8

Therefore, a potential instrument for local public corruption is a proxy for state-capital isolation. We obtain state-capital isolation data from the study of Campante and Do (2014). We use the state-capital isolation value for the earliest year available in the study—i.e., 1920. This ranges from 0 to 1 with lower (higher) values denoting higher (lower) capital isolation. We conjecture that state-capital isolation in 1920 will have a predictive power regarding the level of local (i.e., state-level) public corruption in the 1985–2013 period (i.e., the inclusion restriction). At the same time, we assume that the necessary exclusion restriction is met. Why state-capital isolation in 1920 would affect the lending activity of banks directly in the period of the study is unclear, and is unlikely to be the case. The results of these 2SLS-IV estimations regarding our main hypothesis H1 using quarterly frequency data are available in Panel A of Table 10.

The first-stage results in the lower part of model 1 and 4 of Panel A of Table 10 show that the capital isolation variable in 1920 (CAPIS1920) has a negative and significant association at the 1% level with local public corruption in the 1985–2013 period.Footnote 9 Note that higher values of the CAPIS1920 variable denote less state-capital isolation. Thus, as expected, higher levels of state-capital isolation relate to a higher level of public corruption. Therefore, the capital isolation variable in 1920 is a strong instrument for local public corruption in the 1985–2013 period. Furthermore, the validity of the capital isolation instrument is supported by the under-identification LM test (UIT) and the weak identification Wald F-Test (WIT). The results from the second stage (see the upper part of models 1 and 4 of Panel A of Table 10) lend further empirical support to the findings of the baseline models. In support of hypothesis H1, in these models, we find that local public corruption exerts a negative and significant effect at the 1% level on the two proxies of lending activity. The results from the analogous models that employ yearly frequency data are similar (see models 1 and 4 of Panel B of Table 10).

In an effort to study the robustness of the above conclusion to the instrument chosen, we also adopt a different IV approach, where we consider 2SLS-IV estimations based upon a time-variant instrument. Closely following Cordis and Warren (2014), we use the change of the strength of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) laws in each state. The FOIA laws facilitate the access of the public to information about government activities. Hence, FOIA laws reduce local public corruption by reducing the incentive of government employees and officials to engage in corruption-related illegal activities due to more intense public scrutiny. Cordis and Warren (2014) provide empirical evidence to support this argument. They quantify the strength of the FOIA laws in each US state by using a 0–10 annual score for the 1986 to 2009 period. Next, according to the strength of this score, they classify states into weak FOIA laws states (score of six or less) and strong FOIA laws states (score of seven or more). Subsequently, they show that corruption decreases in the states that transition from weak to strong FOIA laws. However, this effect is evident after seven years. In the short term, after the transition from weak to strong FOIA laws, the conviction rate increases because of a higher possibility of corruption-related crime detection in the previous years. The reduction in local public corruption occurs in the long-term (i.e., after seven years) when the negative effect of FOIA laws on the incentives of government employees and officials to engage in corruption activities offsets the short-term detection effect.Footnote 10

We use the evidence of Cordis and Warren (2014) and, similar to Huang and Yuan (2019), we employ—as an instrument of public corruption—a dummy variable that takes the value of one for the years beyond the seventh year after a state has transitioned from weak to strong FOIA laws while it takes the value of zero up to the seventh year after the transition. We expect this transition dummy to exert a negative effect on local public corruption (i.e., the inclusion restriction), while it is not likely that this transition, which occurred at least seven years ago, would directly affect the contemporaneous bank lending activity (i.e., the exclusion restriction).Footnote 11 Hence, we employ the sample of banks that are located in the states that have experienced an FOIA laws transition and run the 2SLS-IV estimations. This reduces the number of observations because our instrument, by construction, applies to the states that have experienced such a transition in the period of the study.Footnote 12 The results from the estimations that use quarterly data are available in models 2 and 5 of Panel A of Table 10. Despite the difference in the approach, the main message conveyed by the previous IV exercise holds. As expected, the first-stage results in the lower part of these models show that the FOIA transition dummy exerts a negative and significant at the 1% level effect on public corruption. We also find evidence in support of the validity of the FOIA laws transition dummy instrument through the under-identification LM test (UIT) and the weak identification Wald F-Test (WIT). The second-stage results (see the upper part of the models 2 and 5 of Panel A of Table 10) show, in support of hypothesis H1 that the instrumented local public corruption variable exerts a negative and significant effect at the 1% level on the two proxies of lending activity. The findings from the models that use yearly frequency are similar (see models 2 and 5 of Panel B of Table 10).

As a final IV exercise, we provide results from models that employ both the instruments. This exercise is important as it allows us to perform also the test for over-identification by Hansen (OIT). The results from these estimations are available in models 3 and 6 of Panel A and Panel B of Table 10 for quarterly and yearly data, respectively. The first-stage findings in the lower part of these models show that both these two instruments retain their negative and significant effect at the 1% level on local public corruption. Furthermore, the validity of the instruments is also supported by the insignificant p-value of the Hansen over-identification test (OIT) in three out of the four models. The second-stage findings (see the upper part of models 3 and 6 of Panel A and Panel B of Table 10) show that the effect of the instrumented local public corruption on the two proxies of lending activity remains negative and significant at the 1% level.

Overall, the results of the 2SLS-IV estimations lend additional empirical support to hypothesis H1, which posits that local public corruption would exert a negative effect on bank lending activity.Footnote 13 Furthermore, they provide evidence that this association has a causal link.

Perceptions-Based Measures of Local Public Corruption

We also perform estimations that employ perception-based measures of local public corruption. Given that the conviction-based measure of corruption gauges the level of exposed corruption in a state, using perception-based measures could further enrich the analysis. To this end, we use three perception-based measures of corruption at the state level. These are the illegal corruption index for 2014 by Dincer and Johnston (2015), the inverse (by multiplying with-1) “State Integrity Index” developed by the Center of Public Integrity in 2015, and the index of Boylan and Long (2003). The full definitions of these measures are in Table 1.

These three perception-based corruption measures are available at one point in time. This means that they do not exhibit time variability. Thus, we follow Smith (2016) and use their values for the whole sample of the study. Furthermore, since these indices are both state-specific and time-invariant, the models that use them as explanatory variables employ regional fixed effects, as defined by the US census, instead of bank- or state-fixed effects. The results from these estimations are available in Table 11.

In models 1–6 in Table 11, we find that all three perception-based indices of local public corruption (DJ, INVINT, and BL) exhibit a negative and significant relationship with bank lending activity, providing further empirical support to hypothesis H1. Next, we test the effect of the interaction terms between the three perception-based measures of local public corruption and the relationship-based lending and monitoring effort proxies on lending activity. In the models that employ the interaction terms, which are time-variant, we also include bank and state-fixed effects and drop the main perception-based indices that are state-specific and time-invariant. The results from this exercise are available in models 7–12 of Table 11. Overall, we find evidence in support of hypothesis H3 regarding monitoring effort. In three models, the interaction between the perception-based measures of local public corruption and the monitoring effort proxy (SAL EX/TE) has a positive and significant relationship with the lending activity variables (see models 7, 8 and 12 of Table 11).

Finally, because the perception-based measures are time-invariant, we also estimate models that use the cross-sectional average of the bank-specific and state-specific variables across the whole period of the study. The results from this exercise are consistent with the findings of Table 11 and, due to space constraints, are available in Table IA.8 of the Internet Appendix.Footnote 14

Summary of Additional Robustness Tests and Further Analysis

Additional Robustness Tests

We perform several additional robustness checks. We replicate the models of the main analysis with an alternative way of obtaining yearly frequency data. In this respect, we follow Casu et al. (2013) and average the quarterly data on an annual frequency to build a dataset of yearly observations. We also take into account that the yearly public corruption measure may include some noise in terms of its time variation (Campante and Do 2014). Hence, we provide estimations that use the time-series average of the conviction-based state-level corruption and the national rank of this cross-time average. We also replicate the models of the main analysis by clustering the standard errors by both state and year, as in Smith (2016), because the main measure of public corruption exhibits both yearly and state variation. Finally, we also estimate models that examine the effect of public corruption on lending growth. The results from these additional robustness exercises are generally consistent with the results of the main analysis. The Internet Appendix presents and discusses these additional tests.

Further Analysis: Heterogeneity by Bank Size, Time Period and Geographic Focus of Banks

We also perform some heterogeneity analysis (we present and discuss these results in the Internet Appendix). We show that the negative effect of local public corruption on lending activity is more evident for smaller banks. This is consistent with the view that smaller banks have a strong focus on the local credit market. Similarly, the benefits of relationship lending and monitoring effect, in terms of alleviating the negative effect of local public corruption on lending, are more pronounced for smaller banks. We also find that the negative effect of corruption on lending persists in the period after the Riegle-Neal Act of 1994 that abolished regulatory restrictions on interstate banking and interstate branching. However, this effect is more evident for banks with single-state operations, which represent the large majority of US commercial banks. These findings are consistent with previous evidence which shows that, even after the deregulation in geographic restrictions, most US banks still concentrate their business in their home state (Goetz et al. 2016).

Conclusion

The literature that explores the effects of corruption on economic outcomes mostly focusses on emerging and less developed economies, where public corruption is considered more prevalent in comparison with more advanced economies. This is also the case when it comes to the investigation of corruption-related issues in bank lending. Recently, however, a growing stream of research focusses on the effects of public corruption in advanced economies such as the US and provides evidence that it reduces firm transparency and performance (e.g., Dass et al. 2016; Brown et al. 2019).

In a sensible extension of this literature, we investigate the effect of local public corruption on the lending activity of US banks. We find that public corruption exerts a negative and significant effect on lending. These results indicate that, by inducing information asymmetry in the lending market, public corruption discourages the provision of bank credit. Therefore, reduced access to bank credit could be a channel through which public corruption could hamper local economic development even in very advanced economies such as the US.

We also find that relationship lending and monitoring lessen the negative association between public corruption and lending activity. These findings further corroborate that local public corruption prompts the information asymmetry concerns of lenders. To some extent, banks that place emphasis on acquiring information on borrowers and engage in stronger monitoring effort could overcome the information asymmetry that stems from public corruption. Hence, from a managerial standpoint, such bank strategies could be beneficial for banks located in high public corruption areas.

From a public policy standpoint, one could view the findings of this study in conjunction with the studies which show that public corruption exerts negative effects on the outcomes of US firms (e.g., Dass et al. 2016; Brown et al. 2019). Combating public corruption could not only directly improve the performance of US businesses but could also facilitate, through a positive spillover to the banking sector, access to credit. Overall, these findings endorse the need to reshape the policy agenda regarding corruption in the US; and also in other very advanced economies. It is important to revisit the view that public corruption is a source of harmful economic outcomes mostly in less developed and emerging economies and not as much in very advanced economies.

Notes

The variable is taken as thousands of $ deflated using the CPI.

Using the same values of a lower frequency explanatory variable to match observations of a higher frequency dependent variable is not uncommon in the banking literature. Anginer et al. (2014), for example, use as explanatory variables bank regulation measures, which exhibit a triennial frequency, to models where the dependent variables are annual bank performance measures. The justification the authors provide is that bank regulations are slow to change in a short time frame. Similarly, public corruption, being an institutional quality characteristic, is not likely to change significantly during the quarters of the same year. Hence, the approach of assigning the yearly values of local public corruption to the four quarters of the same year is consistent with the approach of Anginer et al. (2014).

We thank an anonymous referee for motivating us to perform estimations based on yearly data.

It comprises information from nonfarm payroll employment, average hours worked in manufacturing by production workers, the unemployment rate, and wage and salary disbursements deflated by the consumer price index.

Nationally-chartered banks are supervised by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) which is a federal supervisor. Both state and federal supervisors (the Federal Reserve or the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) supervise state-chartered banks. During the period of our sample (i.e., since the 1980 s) different charters do not imply significant regulatory or activities permission differences. For an overview of the bank supervision system in the US see Agarwal et al. (2014).

In addition to the instrumental variable analysis, we treat this concern in several other ways. In our baseline models we use bank fixed effects, which account for bank charter type and, hence, the type of bank supervisors. We also perform additional estimations (available on request) that instead of bank fixed effects use bank charter type dummies. Furthermore, Agarwal et al. (2014) show that main reason that state bank supervisors are more lenient than their federal counterparts is because they also take into account the local (i.e., state) economic conditions. In our baseline models we have used the unemployment rate as a proxy for the local economic conditions as well as the state coincident index. Hence, these models also take into account the main source of the leniency of the state supervisors. It is also important to note that Agarwal et al. (2014) test and reject the hypothesis that the leniency of state supervisors could stem from local public corruption.

The extant literature provides additional empirical support the relationship of both of these accountability-reducing mechanisms with corruption [see, for example, Brunetti and Weder (2003) and Costas- Pérez et al. (2012)]. Brunetti and Weder (2003) argue that local media coverage increases the costs incurred from public officials in engaging in corruption-related activities because of higher chance of detection and punishment. Costas- Pérez et al. (2012) provide evidence that voters react to corruption scandals by significantly decreasing the chance of public officials involved in such cases being re-elected to office. They also find that local media coverage enhances this effect.

In the first stage we also include all the other control variables but, for the convenience to the reader, report only the instrument results. Note also that the in the models that use capital isolation as an instrument we do not include state-fixed effects because capital isolation is state-specific and time-invariant. Instead, we use region-fixed effects based on the US census classification.

Vadlamannati and Cooray (2017) provide similar cross-country evidence that the adoption of FOIA laws reduces corruption with a lag (i.e., in the longer term).

One potential caveat is that the transition dummy of the state FOIA laws, which has at least a seven-year lag from contemporaneous lending, might correlate with the contemporaneous strength of the state FOIA laws. Because of the negligible state ownership of the US banking sector and because FOIA laws are specific to the public sector it is not likely that loan officers will take into account the contemporaneous FOIA laws in a stand-alone manner when they decide to grant credit. However, they could take them into account in cases where a loan application involves public officials misusing the public office (e.g., through bribery and nepotism). In such cases, we conjecture that the involvement of a public official in this illegal transaction would still constitute a case of corruption. However, we err on the side of caution and assume that loan officers would take into account the contemporaneous strength of the FOIA laws, which could correlate with our instrument, independently from the contemporaneous level of public corruption. We treat this issue in two ways. Firstly, we run models that include the contemporaneous strength of the FOIA laws and the results of the 2SLS-IV estimation still hold. Secondly, we use models that only comprise the contemporaneous strength of the FOIA laws together with bank, state and time effects as explanatory variables. Then, we use the residuals of this model as dependent variable in the 2SLS-IV estimations. The results are robust to this exercise and available on request. We thank an anonymous referee for raising this issue and motivating us to perform these additional tests.

These states are the following: Idaho (ID), Nebraska (NE), New Hampshire (NH), New Jersey (NJ), New Mexico (NM), North Dakota (ND), Pennsylvania (PA), South Carolina (SC), Texas (TX), Utah (UT), Washington (WA) and West Virginia (WV). For further details see Cordis and Warren (2014) and the associated Internet Appendix of their article.

We note the larger coefficients in the 2SLS-IV models of Table 10 in comparison with the baseline models of Table 5. This is similar to other studies that examine the effects of US local public corruption on firm outcomes (e.g., Dass et al. 2016; Smith 2016). However, we can still infer from the 2SL-IV models of Table 10 a significant negative causal effect of local public corruption on bank lending activity. For the economic interpretation of the effect, we err on the side of caution and use the more conservative results from the baseline models in Table 5.

We also perform additional tests. We estimate models with yearly frequency data. The results from this analysis, available upon request, show that two of the three perceptions-based measures of corruption have a negative and significant effect on lending activity. We also perform estimations for the post-1999 period, given that the three perceptions-based measures reflect post-1999 perceptions, and the findings are consistent.

References

Acharya, V. V., Berger, A. N., & Roman, R. A. (2018). Lending implications of US bank stress tests: Costs or benefits? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 34, 58–90.

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. (1999). Rents, competition, and corruption. American Economic Review, 89(4), 982–993.

Agarwal, S., & Ben-David, I. (2018). Loan prospecting and the loss of soft information. Journal of Financial Economics, 129(3), 608–628.

Agarwal, I., Duttagupta, R., & Presbitero, A. F. (2019). Commodity prices and bank lending. Economic Inquiry: In press.

Agarwal, S., Lucca, D., Seru, A., & Trebbi, F. (2014). Inconsistent regulators: Evidence from banking. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(2), 889–938.

Ahn, S., & Choi, W. (2009). The role of bank monitoring in corporate governance: Evidence from borrowers’ earnings management behavior. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(2), 425–434.

Allen, F., Carletti, E., & Marquez, R. (2011). Credit market competition and capital regulation. The Review of Financial Studies, 24(4), 983–1018.

Alon, A., & Hageman, A. M. (2013). The impact of corruption on firm tax compliance in transition economies: Whom do you trust? Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 479–494.

Amore, M. D., Schneider, C., & Žaldokas, A. (2013). Credit supply and corporate innovation. Journal of Financial Economics, 109(3), 835–855.

Anginer, D., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Zhu, M. (2014). How does competition affect bank systemic risk? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 23(1), 1–26.

Barr, A., & Serra, D. (2010). Corruption and culture: An experimental analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 94(11–12), 862–869.

Barth, J. R., Lin, C., Lin, P., & Song, F. M. (2009). Corruption in bank lending to firms: Cross-country micro evidence on the beneficial role of competition and information sharing. Journal of Financial Economics, 91(3), 361–388.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2006). Bank supervision and corruption in lending. Journal of monetary Economics, 53(8), 2131–2163.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2008). Financing patterns around the world: Are small firms different? Journal of Financial Economics, 89(3), 467–487.

Berger, A. N., & Black, L. K. (2011). Bank size, lending technologies, and small business finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(3), 724–735.

Berger, A. N., & DeYoung, R. (1997). Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(6), 849–870.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1995). Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance. Journal of Business, 68(3), 351–381.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2002). Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organisational structure. The Economic Journal, 112(477), F32–F53.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2004). The institutional memory hypothesis and the procyclicality of bank lending behavior. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13(4), 458–495.

Berlin, M., & Mester, L. J. (1999). Deposits and relationship lending. The Review of Financial Studies, 12(3), 579–607.

Besanko, D., & Kanatas, G. (1993). Credit market equilibrium with bank monitoring and moral hazard. The review of financial studies, 6(1), 213–232.

Bharath, S. T., Sunder, J., & Sunder, S. V. (2008). Accounting quality and debt contracting. The Accounting Review, 83(1), 1–28.

Bhat, G., & Desai, H. (2017). Bank Capital and Loan Monitoring. Working paper. Retrieved 3 Jan 2019 from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2789168

Black, L.K., Hancock, D., & Passmore, W. (2007). Bank Core Deposits and the Mitigation of Monetary Policy, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, FEDS working paper 2007-65.

Black, L.K., Hancock, D., & Passmore, W. (2010). The Bank Lending Channel of Monetary Policy and Its Effect on Mortgage Lending, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, FEDS working paper 2010-39.

Black, S. E., & Strahan, P. E. (2002). Entrepreneurship and bank credit availability. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2807–2833.

Boot, A. W., & Thakor, A. V. (2000). Can relationship banking survive competition? The Journal of Finance, 55(2), 679–713.

Boylan, R. T., & Long, C. X. (2003). Measuring public corruption in the American states: A survey of state house reporters. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 3(4), 420–438.

Brown, N. C., Smith, J. D., White, R. M., & Zutter, C. J. (2019). Political corruption and firm value in the US: Do rents and monitoring matter? Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04181-0.

Brunetti, A., & Weder, B. (2003). A free press is bad news for corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 87(7–8), 1801–1824.

Campante, F. R., & Do, Q. A. (2014). Isolated capital cities, accountability, and corruption: Evidence from US states. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2456–2481.

Campello, M., & Larrain, M. (2015). Enlarging the contracting space: Collateral menus, access to credit, and economic activity. The Review of Financial Studies, 29(2), 349–383.

Casu, B., Clare, A., Sarkisyan, A., & Thomas, S. (2013). Securitization and bank performance. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 45(8), 1617–1658.

Cheng, H., Gawande, K., Ongena, S., & Qi, S. (2018). The Role of Political Connections in Mitigating the Adverse Effect of Policy Uncertainty on Banks. Working paper. Retrieved 7 Mar 2019 from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=3003476

Chiorazzo, V., D’Apice, V., DeYoung, R., & Morelli, P. (2018). Is the traditional banking model a survivor? Journal of Banking & Finance, 97, 238–256.

Cole, R. A., Goldberg, L. G., & White, L. J. (2004). Cookie cutter vs. character: The micro structure of small business lending by large and small banks. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 39(2), 227–251.

Coleman, A. D., Esho, N., & Sharpe, I. G. (2006). Does bank monitoring influence loan contract terms? Journal of Financial Services Research, 30(2), 177–198.

Cordis, A. S., & Warren, P. L. (2014). Sunshine as disinfectant: The effect of state Freedom of Information Act laws on public corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 115, 18–36.

Costas-Pérez, E., Solé-Ollé, A., & Sorribas-Navarro, P. (2012). Corruption scandals, voter information, and accountability. European Journal of Political Economy, 28(4), 469–484.

Dass, N., Nanda, V., & Xiao, S. C. (2016). Public corruption in the United States: Implications for local firms. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 5(1), 102–138.

Dass, N., Nanda, V. K., & Xiao, S. C. (2018). Geographic Clustering of Corruption in the US. Working paper. Retrieved 15 Jan 2019 from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2981317

De Gregorio, J., & Guidotti, P. E. (1995). Financial development and economic growth. World Development, 23(3), 433–448.

DeBacker, J., Heim, B. T., & Tran, A. (2015). Importing corruption culture from overseas: Evidence from corporate tax evasion in the United States. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 122–138.

Delis, M. D., Kouretas, G. P., & Tsoumas, C. (2014). Anxious periods and bank lending. Journal of Banking & Finance, 38, 1–13.

Deng, S., & Elyasiani, E. (2008). Geographic diversification, bank holding company value, and risk. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 40(6), 1217–1238.

DeYoung, R., Distinguin, I., & Tarazi, A. (2018). The joint regulation of bank liquidity and bank capital. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 34, 32–46.

DeYoung, R., & Rice, T. (2004). Noninterest income and financial performance at US commercial banks. Financial Review, 39(1), 101–127.

Diamond, D. W. (1984). Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. The Review of Economic Studies, 51(3), 393–414.

Dincer, O., & Johnston, M. (2015). Measuring Illegal and Legal Corruption in American States: Some Results from the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics Corruption in America Survey. Retrieved 19 Oct 2018 from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2579300

Drechsler, I., Savov, A., & Schnabl, P. (2017). The deposits channel of monetary policy. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4), 1819–1876.

Durnev, A., & Fauver, L. (2011). Stealing from thieves: Expropriation risk, firm governance, and performance. Working paper. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=970969

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C., & Zheng, X. (2016). Collectivism and corruption in commercial loan production: How to break the curse? Journal of Business Ethics, 139(2), 225–250.

Fama, E. F. (1985). What’s different about banks? Journal of Monetary Economics, 15(1), 29–39.

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002). Decentralization and corruption: evidence across countries. Journal of Public Economics, 83(3), 325–345.

Fisman, R., & Miguel, E. (2007). Corruption, norms, and legal enforcement: Evidence from diplomatic parking tickets. Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 1020–1048.

Fisman, R., & Svensson, J. (2007). Are corruption and taxation really harmful to growth? Firm level evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 83(1), 63–75.

Gambacorta, L., & Mistrulli, P. E. (2004). Does bank capital affect lending behavior? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13(4), 436–457.

Glaeser, E. L., & Saks, R. E. (2006). Corruption in America. Journal of Public Economics, 90(6–7), 1053–1072.