Abstract

This article discusses the quest for the mechanical advantage of the wedge in the eighteenth century. As a case study, the wedge enlightens our understanding of eighteenth-century mechanics in general and the controversy over “force” or vis viva in particular. In this article, I show that the two different approaches to mechanics, the one that favoured force in terms of velocities and the one that primarily used displacements—known as the ‘Newtonian’ and ‘Leibnizian’ methods, respectively—were not at all on par in their ability to solve the problem of the wedge. In general, only those who used the Leibnizian concept of force or some related notion were able to get to the conventional results. This article thus rebuts the received view that the vis viva controversy was merely a semantic one. Instead, it shows that different understandings of “force” led to real and pragmatic differences in eighteenth-century mechanics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For one of the most recent extended treatments of the controversy, see Terrall (2004).

Leibniz most famously argues along these lines in his correspondence with Samuel Clarke. See Clarke (1717), for example, pp. 27–31.

For the sake of clarity, I will from here on refer to the measure of mass times velocity as “momentum” and to mass times the square of the velocity as “Leibniz’s force”. As different actors used different terms to refer to this concept, there is no way to do historical justice to all without endangering the intelligibility of the discussion.

See Clarke (1717) for the correspondence with Leibniz and Clarke (1728) for what is generally seen as one of the most acid publications of the controversy. Iltis (1973b), p. 372 for instance writes “[Clarke’s] fanatical devotion to Newton led him to make outrageous insults to those who opposed Newtonian ideas”.

Lagrange (1811), pp. 1–26, 221–246, and Dugas (1955) are still particularly useful overviews of the technical history of mechanics in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as is Capecchi (2012), which largely treats the same figures and issues as Lagrange and Dugas. Yet, these authors focus on the larger conceptual leaps, thus omitting much of what was at stake for contemporaries. None of them discusses the controversy over forces in much detail.

On the calculus dispute, see Hall (1980).

See for instance Bernoulli (1703), p. 84.

Huygens (1986), p. 106, Definition I. In the Latin original, the term is “vi gravitatis”.

Newton (1999), p. 416.

Pourciau (2006).

Pourciau (2006), in particular pp. 201–202.

Newton (1999), pp. 428–429. On inherent force see definition 3, p. 404. The only place where the Principia discusses simple machines and issues pertaining to statics is in the preparatory chapter on axioms, specifically in corollary 2, pp. 418–420, and at the end of the scholium concluding the same chapter, pp. 427–430.

Newton (1999), pp. 404–405, 407. Emphasis added.

Gabbey (1971), pp. 10–11.

Gabbey (1971), in particular p. 17.

Leibniz (1695), in particular pp. 435–438. In the same sense, living force for Leibniz was absolute, whereas dead force was relative: it needed a direction since it depended on the situation with respect to other bodies.

See for instance his arguments in Clarke (1717), pp. 108–111 and 252–255.

See Gabbey (1971), pp. 47–48 for the importance of the passivity of bodies in Newton’s thought.

On the contrary, Newton argued in Query 31 of his Opticks that “active Principles, such as are the cause of Gravity [...] and the cause of Fermentation”, would be needed in order to maintain the amount of motion in the world, as that amount was always decreasing: in other words, Newton argued, in opposition to Leibniz, that some outside processes were needed in order to maintain the world in its present state; see Newton (1952), p. 399.

Clarke (1717), pp. 336–341.

As Iltis (1967), pp. 385–393, (1970), p. 140, explains, however, this became a commonplace practice only well into the nineteenth century, after contributions of amongst others Lagrange, Laplace, and Whewell. Even in Lagrange’s own celebrated Mécanique analytique this distinction is still troubled. Whereas in his first chapter on the principles of statics, Lagrange defines “force” as quantity of movement, in the second part of the book, on dynamics, Lagrange talks about a “force accélératrice”, thus continuing to obscure the discrimination between the two concepts. See Lagrange (1811), pp. 1, 224, 228–229.

Papineau (1977), in particular p. 141. As we have seen above, the works of Galileo and Huygens were of course of great important as well as shared framework.

See Kuhn (1996/1962), in particular pp. 35ff.

Van Musschenbroek (1739), p. 161.

In this particular section, I use “force” and “impulse” in their present meaning. As we will see, the historical actors did not always clearly distinguish between hitting a wedge at speed, in which case “impulse” comes into play, and pressing it down, in which case one will use “force” as it is understood nowadays.

Broek (1986), “Preface to the first edition”. In the prefaces of the subsequent editions of 1978, 1982, and 1986, the author expresses the view that the field of engineering fracture mechanics is developing speedily.

La Hire (1695), p. 276. “Je suppose d’abord que les faces du coin [...] ne trouvent aucune résistance [...] c’est-à-dire que les faces du coin sont infiniment polies, & que le corps ny le coin ne peuvent faire aucune impression l’un sur l’autre, ny changer leur figure par leur rencontre. Je suppose encore que le corps ne peut faire aucun ressort, & que toute la résistance qu’il a à être séparé, n’est que dans les liens qui sont dans la ligne selon laquelle il doit être séparé par l’effort du coin”. For reasons of precision, I will not rely on eighteenth-century translations. Since modern editions do not exist in most cases, translations from the originals are mine in what follows, unless stated otherwise.

See Brühwiler and Wittmann (1990) for the wedge splitting test. Similar cases in which the wedge is used in order to simplify fracture mechanics can be found in Broek (1986), see for instance p. 87. The wedge is used here because it allows for the control of direction of the fracture: an ideal wedge will only split its object vertically. I have not been able to find any modern treatment of the wedges in which all the mentioned factors of friction, fracture and deformation are explicitly discussed: this most likely has to do with the fact that these different factors are treated by different sciences. Typically, modern engineering uses the wedge to idealize cases such that some of the problems will drop out of the equations.

’s Gravesande (1742), I, xx. “Mira de hac machinâ est sententiarum varietas. Qui maximâ cum curâ examinarunt sunt de la Hire & Varignon”.

On the history of the inclined plane, see for instance Lagrange (1811), pp. 8–10.

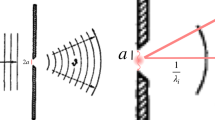

Descartes (1963), pp. 805–807. “car la force dont on frappe dessus agit comme pour le faire mouvoir suivant la ligne BD, et le bois ou autre corps qu’il fend ne s’entr’ouvre [...] que selon la ligne AC. De façon que la force dont on pousse ou frappe ce coin doit avoir même proportion à la resistance de ce bois [...] que la ligne AC à la ligne BD”. See the figure on p. 807.

Capecchi (2012), p. 169.

Wallis (1670–1671), p. 684. “Sitque amolitio Obicis (contra directionem suam) ad progressum Virium (secundum directionem suam,) ut CC ad DA, seu ut c ad d, (quippe dum detruditur Cuneus per totam suam Altitudinem DA, dirimitur Obex per totam ipsius Crassitiem CC, & in toto processu proportionaliter)”, see also figure 309.

René Descartes to Marin Mersenne, July 1638. Part of this letter is reproduced in Capecchi (2012), pp. 164–165.

Part of Bernoulli’s letter to Varignon was printed in Varignon (1725), II, pp. 174–176. For explanations of Bernoulli’s principle and its historical significance, see Capecchi (2012), in particular pp. 6–7, 204–206; Dugas (1955), pp. 231–233; Lagrange (1811), pp. 20–23; Hankins (1970), pp. 198–203. The principle of virtual velocities can be generalized only if infinitesimally small displacements are used, something of which Descartes was already aware. Since this requirement does not influence the cases discussed here, however, I will ignore it.

Capecchi (2012), p. 209.

Iltis (1970).

Lagrange (1811), see pp. 20–23 for his take on the history of the principle in statics.

Varignon (1687), third page of the unnumbered preface. “Enfin je m’appliquai à chercher l’équilibre lui-même dans sa source, ou pour mieux dire, dans sa génération”.

La Hire (1695), pp. 1–2. “c’est une loy naturelle que deux puissances égales doivent demeurer en équilibre [...] c’est sur cette même loy, ou sur cet Axiome que toute la Mécanique est fondée”.

Varignon (1725), I, p. 5, axiom VI; “Les vîtesses d’un même corps [...] sont comme les force motrices qui y font employées, c’est-à-dire, qui y causent ces vîtesses”. See also axiom V, and p. 13, Lemme I.

La Hire (1695), p. 282. “la raison de la puissance N qui pousse le coin étant toujours à la resistance du corps, comme FD à LD”.

La Hire (1695), p. 282.

La Hire (1695), p. 282, proposition LXXXVI: “La puissance qui est appliquée à pousser le coin, a d’autant plus de force que le coin est plus aigu”.

La Hire (1695), p. 288. “les momens de ces puissances seront égaux, puisqu’elles sont entr’elles en raison réciproque des bras du levier [...] l’extrémité D du bras du levier SD ne sçauroit parcourir un espace sans que l’extrémité Q de l’autre bras SQ du même levier ne parcoure un autre espace qui sera au premmier dans la raison du bras SQ au bras SD”. The “Moments” of which La Hire speaks should not be confused with “momentum’.

La Hire (1695), p. 289. “il y en a qui l’ont éxaminé par son mouvement [...] mais ils n’ont pas pris garde avec assez d’attention aux chemins que doivent parcourir les deux corps dans le même temps”.

See La Hire (1695), pp. 8–12, where he does define such things a “moment” and “gravity” by making use of “force”. Yet, this last term itself remains undefined.

Varignon (1725), II, pp. 151–152. Although Varignon refused to mention authors by name, it seems that he referred to La Hire’s solution under “opinion” number IV.

Varignon (1725), II, pp. 171–172.

Varignon (1725), II, p. 155. “en cas d’équilibre entre la force absolue du coup de marteau OF suivant FP, & les résistances en H, K, des côtez HR, KR, de la fente HRK du corps \(\delta \) \(\varepsilon \) \(\lambda \) \(\mu \) à fendre; cette force absolue du coup de marteau [...] sera toûjours à la somme de ces résistances [...] comme le produit du quarré du sinus total par la diagonale DG du parallelogramme DMGN [...]”.

Varignon (1725), II, p. 161. “la force absolue F, dont on le suppose ici frappé ou poussé perpendiculairement à sa base AB en son milieu F, est toûjours à la résistance R, que lui sont ensemble les côtez HR, KR, de cette fente HRK, comme la demi-base AF de ce Coin AEB est à un de ses côtez AE”.

Newton (1999), p. 429. On the wedge, see also p. 420.

One of the most interesting treatments of this aspect of the wedge is given by Whewell (1836) in his book on elementary mathematics. The problem is that, in the analysis of forces, the absolute force is actually working perpendicular to the sides of the wedge, but that in almost all physical cases, it is the sideward component of this absolute force that is doing the work. This becomes very clear from Whewell’s book, as he gives the solution to both the perpendicular and the sideward cases. Whewell however treats the perpendicular case as the more general one, and because of that needs to call in a quite awkward figure to show how the wedge works. See p. 55, corollaries 1 and 2, and figure 49.

Jean Bernoulli to Pierre Varignon, 26 February 1715, quoted in Capecchi (2012), p. 213.

Newton (1999), pp. 418–419. Newton’s decomposition here is correct, of course, but, as explained above, the force exerted on the sides is not the actual force doing the work to push the two sides apart.

Du Chastellet (1759), plate 1, figure 2.

Jacquier and Le Seur (1739–1742), I, p. 28.

Jacquier and Le Seur (1739–1742), I, pp. 28–29; p. 30, note i; p. 59, note k.

This pamphlet, their course prospectus, is usually dated 1714 or 1715. Decades later, Whiston (1749), p. 235, argued that their courses started in 1714; see also Wigelsworth (2010), p. 91. For convenience, I will refer to the pamphlet as “Hauksbee and Whiston (1714)” in what follows. Although Varignon’s book discussed above appeared a decade after these experiments had begun, I have found nothing that indicates Varignon was aware of them. I do not believe he was.

Hauksbee and Whiston (1714), see p. 4 and plate 4, figure 5 of the “Mechanicks” section.

Hauksbee and Whiston (1714), p. 4 and plate 4, figure 6 of the “Mechanicks” section.

For biographical details, see Van Besouw (2016) and references therein.

For all things related to Jan van Musschenbroek, see De Clercq (1997).

In the bibliographical essay that first appeared in the 1742 edition of his work, ’s Gravesande indeed admits that he had taken the machine in the first edition from somebody else. Although he did not mention the authors nor the improvements he had made himself, there can be little doubt he was referring here to Hauksbee and Whiston. See ’s Gravesande (1742), I, xxi.

See ’s Gravesande (1725), I, pp. 46–47.

’s Gravesande (1720), I, p. 32. “Cylindri E,E, separantur, iis interposito cuneo FF, qui pondere M deprimitur, & datur aequilibrium, quando pondus M, se ei addatur cunei pondus, se habet ad pondera P,P, ut semibasis cunei ad illius altitudinem”. Although the title page sets the date at 1720, the book was actually first published in 1719.

’s Gravesande (1720), I, p. 17. “hic agitur de potentiis in obstaculum agentibus, ita ut per resistentiam obstaculi actio potentiae continuo destruatur”. The term “action” is here and elsewhere of course unrelated to the concept of action is it is used in dynamics nowadays.

’s Gravesande (1720), I, p. 18. “Quando spatia percursa sunt in ratione inversa intensitatum, actiones sunt equales”. It should be noted that, as is well known, Newton actually came close to stating Leibniz’s concept of force in propositions 39–41 of book I of his Principia, Newton (1999), pp. 524–534. In modern terms, these propositions can be interpreted as discussing the integration of force over distance, i.e. kinetic energy. They demonstrate that the area of the integration, the “square” in Newton’s own words, is proportional to the square of the velocity. Hence, this integration yields the equivalent to Leibniz’s force. In theory, ’s Gravesande could have found his expression of “the intensity of the action” via these propositions, but I do not believe he actually did. As we will see below, ’s Gravesande soon after this switched to the Leibniz’s concept of force. If he would have been aware of the implications of propositions 39–41, he most likely would have recognized their closeness to Leibniz’s force. However, Newton himself never made this link explicit, and ’s Gravesande attributed the concept to Leibniz and Huygens instead. In the second edition of his Physices elementa, he argued explicitly that he would not back up Newton on these points, see ’s Gravesande (1725), I, the second page of the unnumbered Monitum which opens the volume. “Novam etiam nostram Percussionis Theoriam, quae Leibnitzianam, quam & Hugenianam dicere ausim, de viribus insitis doctroniam pro fundamento habet [...] Quamvis in multis, quae spectant memoratas Theorias, a Newtoniana recesserim sententia [...]”.

’s Gravesande (1720), I, pp. 31–32. “Quando totus cuneus intruditur, spatium ab illo ictu aut ictibus mallei percursum est illius altitudo, quod ideo pro spatio à potentia percurso haberi debet; spatium vero, per quod lignum ab utraque parte cedit, est semibasis cunei. Unde sequitur, Potentiam se habere ad ligni resistentiam, quando aequipollet, ut semibasis cunei ad illius altitudinem”.

’s Gravesande (1720), I, p. 33. “sic regula praecedens ad Experimentum revocatur & eo confirmatur”.

Leupold (1724), p. 49. “Beim Gebrauch werden zwei Gewichte genommen, als hier X 10 Bf. Und Y 2 Bf. Wenn nun die 10 Bfund mit 2 am Keil in aequillibrio stehen sollen, so muss sich die Seite des Keils NN gegen die Basin NO verhalten wie 2 zu 10, oder 1 zu 5”. In both the text and the figure, Leupold seems not to take into account the weight of the wedge itself, which is of course problematic. See Tab. xvii, figure iii.

Leupold (1724), p. 74. “Gegeneinanderhaltung und Beweis, das die einfachen Künst-Zeuge bei gleicher Krafft und Zeit auch gleiches Vermögen haben”; and “der Raum der Last und Krafft [verhalten] sich [allezeit] gegeneinander wie die Proportion der Machine oder die einander glechstehende Krafft und Last selber”.

Leupold’s works appear in the auction catalogue of ’s Gravesande’s library, published as Bibliotheca ’sGravesandiana (1742). Lugduni Batavorum: Verbeek, p. 8.

Allamand (1774), I, xiv–xvii lists some of his critics.

For the experiments which ’s Gravesande used to argue for this position, see ’s Gravesande (1725), I, p. 109ff.

’s Gravesande (1742), I, xxi. Although the cylinders would move along an arc and not in a straight line because of the suspension from above, their direction in the first instance after breaking the equilibrium would of course still be in the horizontal direction. Therefore, the equilibrium conditions are not changed due to the arced path.

’s Gravesande (1725), I, 45.

’s Gravesande (1725), I, pp. 42–45 and plate 8, figure 5.

’s Gravesande (1725), I, p. 47. “Machina haec non repraesentat quae in actione cunei, quo corpora separantur, obtinent; pondera enim P,P, non repraesentant vim qua cylindri inter se cohaerent; sed cylindri singuli dimidio ponderum P,P, ad trochleam fixam trahuntur; in nostra autem machina, ponderibus integris P,P, inter se cohaerent cylindri”. Perplexingly, in the previous scholium on pp. 46–47, ’s Gravesande discussed the case in which the wedge did not fill the cavity, and came to the result of the side of the wedge to half its base following the same geometrical approach as La Hire and Varignon. Both the method and the result strongly contrast with his new experiment. Although I have no explanation for this discrepancy, it evidences again that different methods could lead to different results.

’s Gravesande (1725), I, Caput XV, “De Potentiis obliquis”, p. 49ff. For his definition of the actions of powers, see pp. 22–24. ’s Gravesande used terms like “power”, “pressure”, “force”, and “action” in an idiosyncratic way, but did use them consistently. For a clear example of how his use of the composition approach, see ’s Gravesande (1742), I, p. 78 and plate 12, figure 2.

Following the conventional method, considering the forces on the wedge: the two forces that pull the cylinders together are equal and directed perpendicular to the sides of the wedge, one acting from the left and one from the right. Completing the parallelogram, the diagonal is directed downwards, and represents the weight that pulls the wedge down. The actual force of the weight attached to one of the cylinders is of course in the horizontal direction, via the ropes that connect the weights with the cylinder (see Fig. 1). This force is represented by the horizontal component of the line that represents the force of the cylinder on the wedge. If one draws this line as well (I can fully recommend the reader to actually draw these forces), one has recreated a triangle that is similar to the wedge. The height of this triangle represents the weights pulling the cylinders together, the base represents the weights that pull the wedge down. Hence, the ratio between these forces is represented by the ratio between the height and the base of the wedge.

In the 1725 edition, the chapter on the wedge ends at p. 47, that on composition of forces [De potentiis obliquis] begins on p. 49. In the 1720 edition, these are, respectively, p. 34 and p. 67.

See Hankins (1970) pp. 195–198, for d’Alembert’s fruitless struggles with this problem. D’Alembert too, tried to define force exclusively in terms of momentum.

Desaguliers (1719), p. 42.

Desaguliers (1734), pp. 107–108.

Desaguliers (1734), p. 109.

Desaguliers (1734), p. 109.

Desaguliers (1734), pp. 109–110.

Desaguliers (1734), p. 110, sic, emphasis removed.

See Desaguliers (1734), pp. 111–112 and plate 11, figure 6.

Desaguliers (1744), v–vi, sic.

Van Musschenbroek (1739), p. 158. “Wanneer een lighaam [...] gescheiden wordt door de wigge, zo wordt de magt, drukkende den rug van de wigge, tot den weerstand der deelen, welke gescheiden worden, vereischt, gelyk de hoogte van de wigge tot haare langte, dat is als BC tot BA”. Van Musschenbroek’s terminology is a little confusing here because of the fact that he considers a wedge moving sidewards instead of downwards into a body, in contrast to the other authors discussed here. Because of that, height and length interchange their meaning in his text.

Van Musschenbroek (1739), p. 159. “Wanneer men met zeker werktuig de proeven doet, bevindt men dat ze net met den regel overeenkoomen, zodat men verzekerd kan zyn, dat de regel goed is, en wy in het redeneeren niet gemist hebben, schoon sommigen hier tegens geschreeven hebben”. Van Musschenbroek uses the indefinite plural “men”, equivalent to the French “on”, which I have translated as “one”. Because of that, the grammer of the translation does not agree entirely with the original.

“Wanneer dan de wigge ADCO gantsch in dit stuk ingelsagen zal zijn, heeft de wigge geloopen den weg DC, terwijl het stuk B van een gescheurd en dus geloopen is den weg AO, waarom de snelheden hier zyn als DC tot AO”. Van Musschenbroek (1739), p. 161, emphasis added.

Van Musschenbroek (1739), p. 161. “gelyk door den wydvermaarden Heer s’Gravesande aangetoond is”.

That Van Musschenbroek used single velocities as the measure of force in 1739 is quite strange given that he had already professed his allegiance to the Leibniz’s force in his first oration of 1723. In the wake of ’s Gravesande’s work on free fall of 1722, Van Musschenbroek claimed that experiments had determined that force was proportional to the square of the velocity, a ratio for which he explicitly credited Huygens and Leibniz. See Van Musschenbroek (1723), p. 28. “Experimenta [...] nuper duplicatam velocitatis rationem determinaverunt”, I owe this reference to Pieter Present.

Van Musschenbroek (1739), p. 84. “de werkingen der voortduuwende Magten zyn in eene vermenigvuldigde reden, zo van de snelheden als van de grootheden der hinderpaalen”.

Van Musschenbroek (1748), p. 75. “actiones potentiarum in ratione composita ex spatiis percursis & magnitudine obstaculorum”.

Van Musschenbroek (1748), p. 126. “spatia percursa”.

See Van Musschenbroek (1762), I, p. 131.

Van Musschenbroek (1748), p. 126. “Eodem omnia in cuneo duplici pari se habent modo”.

Van Musschenbroek (1762), I, plate 7.

Van Musschenbroek (1762), I, p. 132, section CCCCLXIV, “uti dorsum Cunei ad ejus longitudinem”.

Van Musschenbroek (1762), I, p. 132. “Hoc est, potentia movens est ad pondus, ut dorsum cunei ad duplam longitudinem”.

Van Musschenbroek (1762), I, p. 132, section CCCCLXV.

Jacquier and Le Seur (1739–1742), I, pp. 28–30, in particular note i; p. 59, note k.

Guicciardini (2015), p. 356.

Guicciardini (2015), pp. 358–359.

Part of the acknowledgement is cited in Guicciardini (2015), p. 355.

Allamand (1774), I, xii.

This episode is discussed by Allamand, ’s Gravesande’s biographer, who has used parts of the now lost correspondence between the two philosophers. See Allamand (1774), I, xvii–xix. The two papers of Calandrini and ’s Gravesande are reprinted in the same volume, pp. 269–284.

Guicciardini (2015), p. 367. As explained above in note 90, a concept similar to Leibniz’s force had been discussed by Newton in propositions 39–41 of book I of the Principia. It is possible that Calandrini and ’s Gravesande were aware of the fact that Newton’s propositions could inform their own discussions of free fall, but I have seen no evidence that they actually made use of them, nor have I seen any obvious reference to Leibniz or living force in the notes on propositions 39–41 of the Geneva edition.

Jacquier and Le Seur (1739–1742), I, p. 59, note k. “Momentum cunei est ut factum (101), ex vi impressa a malleo in cunei velocitatem, seu in spatium quod dat tempre percurrit cuneus [...] ”. In the same note, the solution is given: “(in casu aequilibrii) vis cunei ad ligni resistentiam [erit], ut cunei altitudo ad latitudinem ipsius basis”.

Nollet (1745), III, p. 126. “d’où il suit cette proposition générale, la puissance est à la résistance, dans le cas d’équilibre, comme la base du coin est à sa hauteur”.

See the volume by Pyenson et al. (2002) for biographical details concerning Nollet.

Nollet (1745), III, p. 126. “dans le cas de l’équilibre, le poids k doit être à la somme des deux autres en raison réciproque des vîtesses”.

Papineau (1977), pp. 138–140.

References

Allamand, J.N.S. 1774. Oeuvres philosophiques et mathématiques de Mr. G. J. ’sGravesande, 2 vols. Amsterdam: Rey.

Bernoulli, Jacques. 1703. Démonstration générale du centre de balancement ou d’oscillation, tirée de la nature du Levier. Mémoires de mathématique et de physique, tirés des registres de l’Académie Royale des Sciences de l’année mdcciii, 78–84.

Bernoulli, Jacques. 1704. Démonstration du principe de M. Hughens, touchant le centre de balancement, & de l’identité de ce centre avec lui de percussion. Mémoires de mathématique et de physique, tirés des registres de l’Académie Royale des Sciences de l’année mdcciv, 136–142.

Brenni, Paolo. 2002. Jean Antoine Nollet and physics instruments. In The art of teaching physics: The eighteenth-century demonstration apparatus of Jean Antoine Nollet, ed. L. Pyenson, and J.F. Gauvin, 11–27. Sillery: Septentrion.

Broek, David. 1986 [1974]. Elementary engineering fracture mechanics, 4th ed. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff.

Brühwiler, E., and F.H. Wittmann. 1990. The wedge splitting test, a new method of performing stable fracture mechanics tests. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 35: 117–125.

Capecchi, Danilo. 2012. History of virtual work laws: A history of mechanics prospective. Milan: Springer.

Clarke, Samuel. 1728. A Letter from the Rev. Dr. Samuel Clarke to Mr. Benjamin Hoadly. Philosophical Transactions 35: 381–388.

Clarke, Samuel. (ed.). 1717. A Collection of Papers, Which passed between the late Learned Mr. Leibnitz and Dr. Clarke. London: Knapton.

De Clercq, Peter. 1997. At the sign of the Oriental Lamp: The Musschenbroek workshop in Leiden, 1660–1750. Rotterdam: Erasmus.

De Pater, C. 1988. Willem Jacob ’s Gravesande: Welzijn, wijsbegeerte en wetenschap. Baarn: Ambo.

Desaguliers, J.T. 1719. A System of experimental philosophy, Prov’d by mechanicks. London: Creake.

Desaguliers, J.T. 1734. A course of experimental philosophy, vol. I. London: Senex.

Desaguliers, J.T. 1744. A Course of experimental philosophy, vol. II. London: Innys.

Descartes, René. 1637 [1963]. Explication des engins par l’aide desquels on peut avec une petite force lever un fardeau fort pésant. In Oeuvres philosophiques, tome premier (1618–1637): textes établis présentés et annotés par Ferdinand Alquié, 802–814. Paris: Garnier.

Du Chastellet, Émilie. 1759. Principes mathématiques de la philosophie naturelle. Paris: Desaint & Saillant.

Dugas, René. 1955. A history of mechanics. New York: Central Book Company.

Ferguson, Eugene S. 1971. Leupold’s “Theatrum Machinarum”: A need and an opportunity. Technology and Culture 12: 64–68.

Gabbey, Alan. 1971. Force and inertia in seventeenth-century dynamics. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 2: 1–67.

Galilei, Galileo. 1960. Galileo Galilei on motion and on mechanics, Comprising De Motu (ca.1590) Translated with Introduction and Notes by I.E. Drabkin; and Le Mecchaniche (ca.1600) Translated with Introduction and Notes by Stillman Drake. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Guicciardini, Niccolò. 2015. Editing Newton in Geneva and Rome: The Annotated Edition of the Principia by Calandrini, Le Seur and Jacquier. Annals of Science 72: 337–380.

Hall, A.Rupert. 1980. Philosophers at war: The quarrel between Newton and Leibniz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hankins, Thomas L. 1965. Eighteenth-century attempts to resolve the vis viva controversy. Isis 56: 281–297.

Hankins, Thomas L. 1970. Jean d’Alembert: Science and the enlightenment. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hauksbee, Francis, and William Whiston. 1714. A course of mechanical, magnetical, optical, hydrostatical, and pneumatical experiments. Unspecified pamphlet.

Huygens, Christiaan. 1986 [1673]. The pendulum clock or geometrical demonstrations concerning the motion of pendula as applied to clocks, translated with notes by Richard J. Blackwell. Ames, IA: The Iowa State University Press.

Iltis, Carolyn. 1967. The controversy over living force: Leibniz to d’Alembert. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin.

Iltis, Carolyn. 1970. D’Alembert and the vis viva controversy. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 1: 135–144.

Iltis, Carolyn. 1971. Leibniz and the vis viva controversy. Isis 62: 21–35.

Iltis, Carolyn. 1973a. The decline of Cartesianism in mechanics: The Leibnizian-Cartesian debates. Isis 64: 356–373.

Iltis, Carolyn. 1973b. The Leibnizian-Newtonian debates: Natural philosophy and social psychology. The British Journal for the History of Science 6: 343–377.

Jacquier, Francisci, and Thomae Le Seur. 1739–1742. Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica, acutore Isaaco Newtono, 3 vols. Genevae: Barrillot.

Kuhn, Thomas S. 1996 [1962]. The structure of scientific revolutions, 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lagrange, J.L. 1811 [1788]. Mécanique analytique, nouvelle édition. Paris: Courcier.

La Hire, Philippe. 1695. Traité de mécanique. Paris: L’imprimerie royale.

Laudan, L.L. 1968. The vis viva controversy, a post-mortem. Isis 59: 130–143.

Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. 1686. A brief demonstration of a notable error of Descartes and others concerning a natural law. In Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Philosophical papers and letters, ed. Leroy E. Loemker (1969) [1956] 2nd ed., 296–302. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. 1695. Specimen dynamicum. In Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Philosophical papers and letters, ed. Leroy E. Loemker 1969 [1956], 2nd ed., 435–452. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Leupold, Jacob. 1724. Theatrum machinarum generale. Schauplatz des Grundes mechanischer Wissenschafften. Leipzig: Zunckel.

Newton, Isaac. 1952 [1704]. Opticks, or a treatise of the reflections, refractions, inflections & colours of light. Mineola, NY: Dover.

Newton, Isaac. 1999 [1687]. The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy; a new translation by I. Bernard Cohen, Anne Whitman; assisted by Julia Budenz; preceded by A guide to Newton’s Principia by I. Bernard Cohen. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nollet, Jean Antoine. 1745. Leçons de physique expérimentale, 6 vols. Paris: Guerin.

Nollet, Jean Antoine. 1770. L’art des expériences, ou avis aux amateurs de la physique, 3 vols. Paris: Durand.

Papineau, David. 1977. The vis viva controversy: do meanings matter? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 8: 111–142.

Pourciau, Bruce. 2006. Newton’s interpretation of Newton’s second law. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 60: 157–207.

Pyenson, Lewis, and Jean-François Gauvin (eds.). 2002. The art of teaching physics: The eighteenth-century demonstration apparatus of Jean Antoine Nollet. Sillery: Septentrion.

Renn, Jürgen, and Peter Damerow. 2010. Guidobaldo del Monte’s Mecanicorum liber. Berlin: epubli.

Schaffer, Simon. 1995. The show that never ends: Perpetual motion in the early eighteenth century. British Journal for the History of Science 28: 157–189.

’s Gravesande, G.J. 1720. Physices elementa mathematica, experimentis confirmata. Sive introdcutio ad philosophiam newtonianam, 2 vols. Lugudni Batavorum: Van der Aa.

’s Gravesande, G.J. 1725. Physices elementa mathematica, experimentis confirmata. Sive introdcutio ad philosophiam newtonianam, 2nd ed., 2 vols. Lugudni Batavorum: Van der Aa.

’s Gravesande, G.J. 1742. Physices elementa mathematica, experimentis confirmata. Sive introdcutio ad philosophiam newtonianam, 3rd ed., 3 vols. Leidae: Langerak.

Shapin, Steven. 1981. Of Gods and kings: Natural philosophy and politics in the Leibniz-Clarke disputes. Isis 72: 187–215.

Smith, George E. 2006. The vis viva dispute: A controversy at the dawn of dynamics. Physics Today 59: 31–36.

Terrall, Mary. 2004. Vis viva revisited. History of Science 42: 189–209.

Van Besouw, Jip. 2016. The impeccable credentials of an untrained philosopher: Willem Jacob ’s Gravesande’s career before his Leiden professorship, 1688–1717. Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 70: 231–249.

Van Musschenbroek, Petrus. 1723. Oratio de certa methodo philosophiæ experimentalis. Trajecti ad Rhenum: Guilielum van de Water.

Van Musschenbroek, Petrus. 1739. Beginsels der Natuurkunde, Beschreeven ten dienste der Landgenooten. Leyden: Luchtmans.

Van Musschenbroek, Petrus. 1748. Institutiones physicae, conscriptae in usus academicos. Lugduni Batavorum: Luchtmans.

Van Musschenbroek, Petrus 1762. Introductio ad philosophiam naturalem, 2 vols. Lugduni Batavorum: Luchtmans.

Varignon, Pierre. 1687. Projet d’une nouvelle méchanique. Paris: Martin, Boudot, & Martin.

Varignon, Pierre. 1725. Nouvelle mécanique ou statique, 2 vols. Paris: Jombert.

Wallis, Johanne. 1670–1671. Mechanica: sive, de motu, tractatis geometricus, 3 vols. Londin: Godbid & Pitt.

Whewell, W. 1836 [1819]. An elementary treatise on mechanics: Designed for the use of students in the university, 5th ed. Cambridge: Deighton.

Whiston, William. 1749. Memoires of the Life and Writings of Mr. William Whiston. London: Whiston.

Wigelsworth, Jeffrey R. 2003. Competing to popularize Newtonian philosophy: John Theophilus Desaguliers and the preservation of reputation. Isis 94: 435–455.

Wigelsworth, Jeffrey R. 2010. Selling science in the age of Newton: Advertising and the commoditization of knowledge. Farnham: Ashgate.

Yoder, Joella G. 1988. Unrolling time: Christiaan Huygens and the mathematization of nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

A first version of this article was written during a stay in Museum Boerhaave in Leiden; I thank the museum and its staff for their help and for granting me access to their collection. I wish to express my gratitude to Ad Maas and Steffen Ducheyne for useful discussion on the first version of this article, and to Niccolò Guicciardini for helpful comments on the last. Finally, I am indebted to George E. Smith, whose many profound comments and suggestions have been invaluable to both my understanding of eighteenth-century mechanics in general and the development of this article in particular.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Niccoló Guicciardini.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Besouw, J. The wedge and the vis viva controversy: how concepts of force influenced the practice of early eighteenth-century mechanics. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 71, 109–156 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-016-0182-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-016-0182-3