Abstract

This is the first part of a larger project that aims to develop a cross-categorical semantic account of a broad range of as if constructions in English. In this paper, we focus on descriptive uses of as if with regular truth-conditional content. The core proposal is that as if-phrases contribute hypothetical (if-like) and comparative (as-like) properties of situations, which are instantiated by an event, state, or larger situation when it resembles in some relevant respect its counterparts in selected stereotypical worlds described by the clause embedded under as if. We motivate and develop this situation-semantic analysis in detail for examples like Pedro danced as if he was possessed by demons where the modifying as if-adjunct is used to inferentially convey the manner of a reported activity. We extend this analysis to as if-complements of perception verbs in reports like The soup tastes as if it contains fish sauce, offering an alternative to conceptually problematic approaches that assimilate such perceptual resemblance reports to propositional attitude ascriptions. We also examine the predicative function of as if in examples like The state of the house is as if a tornado passed through it where the as if-phrase denotes a hypothetical comparative property of the nominal subject.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We do not take this classification to be exhaustive. For instance, in Sect. 3.6 we discuss ‘causal uses’ of as if that do not slot neatly into any of these four categories.

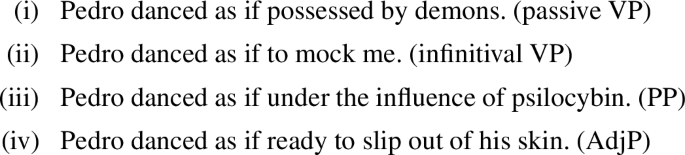

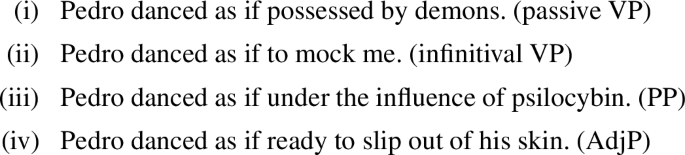

While almost all of the as if-phrases considered in this paper involve embedded finite TPs, as if can combine with a range of other constituents (thanks to Simon Charlow (p.c.) for these examples):

Perhaps these are all elliptical for sentential clausal variants, but this requires careful argument. In any case, we suspect that much of what we say about the semantics of as if applies to examples like (i)–(iv) as well.

TEI XML Edition, available online at http://helsinkicorpus.arts.gla.ac.uk/.

Corpus of Contemporary American English (Davies, 2008): available online at http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/.

Throughout this paper, we interpret ‘perceptual resemblance report’ broadly enough to include such epistemic uses.

We defend our use of the moniker ‘exclamatory as if’ in the second part of our project, arguing that these utterances are bona fide exclamations.

While Clueless uses are widely thought to originate in 1980s Valley Girl talk, Brinton reports that this use was already present in early twentieth-century American colloquial speech, citing an example (via OED) from Frank Norris’s (1903) The Pit: A Story of Chicago.

We are grateful to a reviewer for Sinn und Bedeutung 23 for bringing Sebastian Bücking’s paper to our attention. We are also very grateful to Sebastian himself for helpful correspondence in later stages of this project.

One can also intervene with possibility modals such as might, probably would, and thinks he might.

This example shows how adverbial modification with as if can also occur in imperatival constructions, where the as if-phrase specifies the manner of activity being ordered, requested, advised, and so forth (see Kaufmann, 2012; Condoravdi and Lauer, 2012 for more on the functional heterogeneity of imperatives). Though we present other examples of imperatival manner uses in this paper, we focus mostly on declarative sentences and will not offer an analysis of the imperative case.

An anonymous reviewer wonders if this data might be explained by restrictions on gapping (ellipsis) of material between as and if. While this suggestion deserves further investigation, we think that such an explanation is unlikely to succeed, as the modifiers only, even, and except can directly attach to a conditional clause, indicating that in general an if-clause can anchor these particles.

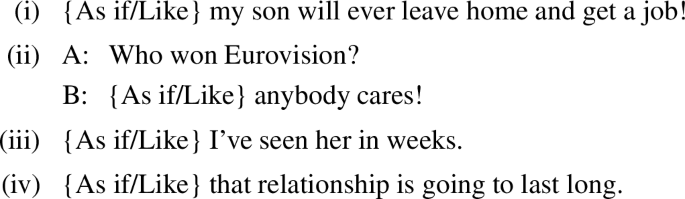

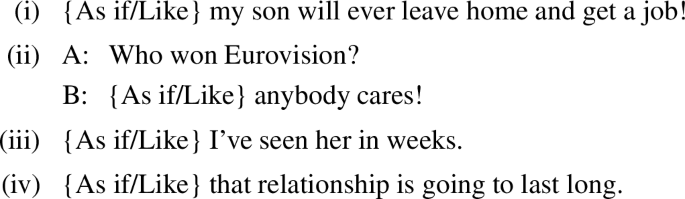

On the other hand, as Camp and Hawthorne (2008) and Camp (2012) observe, independent as if-clauses license NPI any and ever, as well as strong NPIs like in weeks and last long, in which respect they pattern like “sarcastic” like:

We account for the NPI-licensing behavior of exclamatory independent uses in the second part of our study focusing on these constructions.

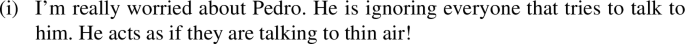

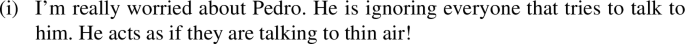

As previously discussed, this is especially vivid with exclamatory uses, where a speaker rejects the proposition expressed by the complement.

The status of both SA and SDA for indicative and subjunctive conditionals is highly controversial. Our point is not that SA/SDA are invalid/valid and that the corresponding principles for as if-sentences are also invalid/valid, but only that we witness similar kinds of apparent failures of antecedent strengthening in both cases, and we can intuitively draw simplification inferences from both if-conditionals with disjunctive antecedents and as if-clauses with disjunctive complements in a broad range of cases.

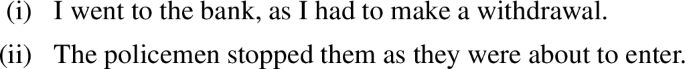

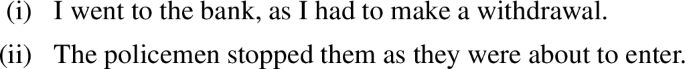

Admittedly, not all uses of as involve comparativity, as pointed out by a reviewer with the following causal and temporal as-clauses (see Zobel, 2016 for more examples):

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for this example.

Lewis (1968) himself takes events to be transworld—he identifies events with classes of spatio-temporal regions that can span multiple worlds. While our counterpart-theoretic treatment of events and other situations is inspired by Lewis’s work on modality, any conceptual errors associated with (52) are our own.

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for raising this objection.

In some cases, the situational counterparts used in evaluating as if-phrases needn’t even share the same participants, or their individual counterparts (thanks to Alex Kocurek and Daniel Harris for both suggesting examples of this kind):

We deviate slightly from Kratzer whose “conversational backgrounds” are functions from worlds to sets of propositions.

Thanks to Ashwini Deo for this example and discussion.

Breckenridge (2007) rejects a similarity-based account of looks as if reports on the basis of such examples.

Observe that (60) significantly improves by inserting normally or usually, or by making the embedded subject an arbitrary pro (thanks to Ashwini Deo for the latter suggestion):

(i) Melania is angry but she’s not acting as she would {normally/usually} act if she were angry.

(ii) Melania is angry but she’s not acting as one would if one were angry.

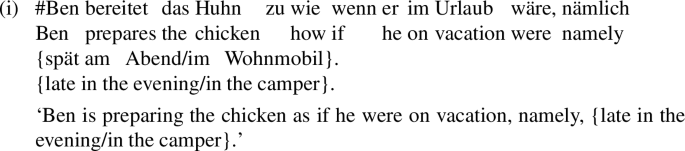

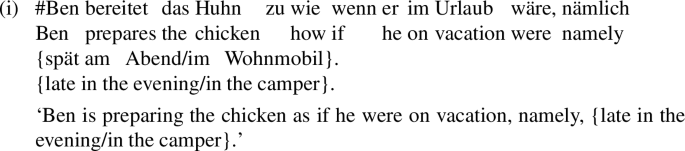

Bücking (2017) argues that German verb-based HCCs can relate to a variety of event-internal particularized properties (including internal locative properties) but these HCCs cannot function as external locative or temporal modifiers that “locate events as wholes in space and time”, as shown by his ex. 11:

However, the English translation of (i) sounds fine, as do our temporal and locative examples (64) and (65), suggesting that English as if is more flexible than German wie wenn in that it can be a source of external or internal information about an eventuality.

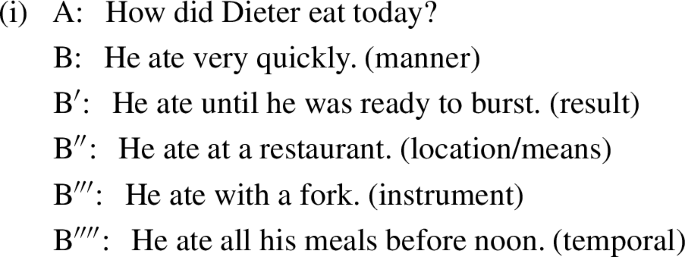

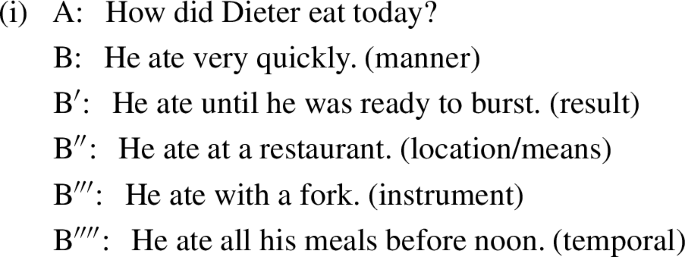

This slight dissonance might be due to the extra pragmatic inference required to interpret the dimension of resemblance as locative, and to competition from the more direct answer The king met Annie in the throne room. Admittedly, more still needs to be said about why the dissonance is greater with a where-question than with a how-question (thanks to a reviewer for raising this point). One reason for the relative lack of oddness with how-questions could be because they readily admit a wider range of answers, as shown below. Such non-selectivity might suffice to render an as if utterance felicitous in response to a how-question, even before the exact dimension of R-resemblance has been resolved.

Furthermore, if an adaptive process transforms the locative information in (65) into event-internal mode information, we might expect this process to be possible with German HCCs as well. However, as discussed in footnote 24, German HCCs cannot convey external temporal or locative information.

We are grateful to Bücking (2017) for bringing to our attention Umbach and Gust’s research on similarity demonstratives.

Thanks to Rachel Rudolph for helpful discussion.

A reviewer worries that this specification is not strict enough, in that it does not explicitly force co-temporality between counterparts of Pedro’s dancing and his possession by demons. In other words, the worry is that the selection function could return counterparts from worlds in which Pedro is possessed at some other time. However, as we will see, this kind of temporal non-alignment is ruled out by our treatment of tense. During semantic composition, the proposition expressed by the as if prejacent is understood to be associated with a temporal signature that can be inferred on the basis of the tense indicated in the matrix clause, as per Kratzer’s (1998) ‘sequence of tense’ analysis. This occurs in (51) given the absence of independent spatiotemporal specification on the prejacent, which ensures temporal alignment between counterparts of Pedro’s dancing and his possession by demons.

We employ the standard type convention: type e for entities, type t for truth values, and type s for situations.

While Bender and Flickinger (1999) and Brook (2014) treat as if-complements of perceptual source verbs as CPs headed by the complementizer as if, Asudeh (2002) argues that as if-phrases are PPs generated from an ordinary if-CP and preposition as. Although we wish to remain officially neutral about whether as if-phrases are CPs, PPs, or perhaps both CPs and PPs at once, let us note for the record that we do not find Asudeh’s arguments for the PP approach especially persuasive, as these are largely based on uniformities between as if and ordinary as and if—for instance, he observes that as if-phrases take the same pre-modifiers as prepositions and allow for subjunctive mood. We argued in Sect. 2 that as if is as-like and if-like in many respects but the evidence also shows that as if is syntactically and semantically inflexible in ways that are surprising on Asudeh’s proposed treatment.

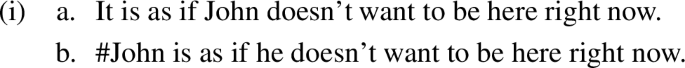

More generally, we are attracted to the idea that interpretive differences for English as if-phrases can arise from variation in their attachment height. The ability for as if to combine directly with a topic situation in LF is a key component of our analysis of exclamatory as ifs in the second part of our project.

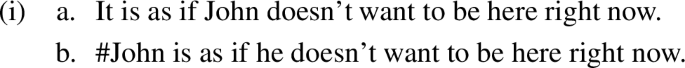

An anonymous reviewer notes the absence of examples with be in the current section, which seem intuitively similar to PRRs though they do not permit the alternation with non-expletive DPs:

We take such examples to be closer to independent as if-phrases than PRRs in that they compose not with a lexical eventive/stative predicate but rather with the topic situation itself. As such, we defer further discussion to follow-up work.

Kratzer’s believe has both an eventuality and “content” argument, where this latter argument is saturable with things believed such as newspaper stories or rumors. However, the content argument isn’t important in what follows and so we ignore it and present a simpler 1-place denotation.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for the second example.

We are grateful to Steven Gross for helpful discussion.

There is still some room to maneuver. Plausibly, the content associated with experiential states is highly context-sensitive. One might say that the context of my first utterance (118) determines a looking content based somehow on my initial perception and creative interpretation of Pedro’s dancing while the context of my second utterance (119) determines a different looking content based on my subsequent reintepretation of the same perceived dancing. With a pliable enough conceptual framework, conclusive counterexamples are hard to come by.

See Breckenridge (2018, Ch. 3) for further discussion of ways of looking, which he analyzes in terms of the determinable-determinate relation.

Ways of experience, like manners of behavior, come in different flavors. A visual experience can have a color character, a shape character, a combined color + shape character, and so forth. There is still work for context in determining exactly which kind of way is being compared in a PRR.

It is an interesting question whether, as Matushansky (2002) argues, the meaning of seem changes across the pair (116). In our neo-Davidsonian framework where both seems denote the property of being a seeming, the question boils down to whether these are the same seemings or not. A friend of ambiguity might claim that (i) there are two kinds of seemings in natural language metaphysics—perceptual seemings with ways but no content, and epistemic seemings with content but no ways; and (ii) the seem in the seems as if claim (116-a) denotes the property of being a perceptual seeming while the seem in the seems that claim (116-b) denotes the different property of being an epistemic seeming. On the other hand, a foe of ambiguity will insist that the seems in (116-a) and (116-b) express one and the same property. On our preferred version of this ‘one seem’ story, the single class of seemings is a motley crew: while all seemings have ways of occurring, some seemings generate a strong enough impulse or push towards believing some content that they are assigned it by the CON function (cf. Asudeh and Toivonen, 2012, who argue that seems that constructions have both an epistemic and a perceptual component).

Glüer herself traces the ambiguity in (125) to the verb look, which functions in the first case as an epistemic modal and in the second case as a quantifier over ways of looking. However, we don’t want to take this route either.

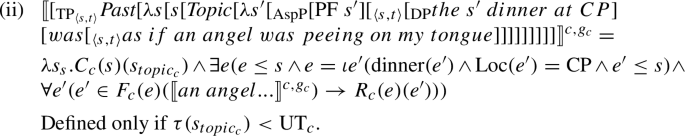

On this aspectless approach, nominal predicative uses of as if pattern similarly to entity-type modification with individual-level predicates (e.g., Hodor is a tall man) as analyzed by Kratzer (1995) on which they lack an eventuality argument at the clausal level, and consequently lack an aspectual projection altogether (though see Chierchia, 1995 for an alternative view of individual-level predication involving generic aspect). A point in favor of this type of analysis is the incompatibility of nominal predicative uses with overt aspectual modifiers, as in *The dinner at Chez Panisse was {being/already} as if an angel was peeing on my tongue.

After the type shift, (139) becomes:

If this event property then combines with the as if denotation (140) before integrating with the perfective operator PF, we end up with a result similar to before:

Since this is not a paper on aspect or the lack thereof in predicative constructions, we do not try to decide between the two compositional processes, both of which serve to illustrate how our hypothetical comparative semantics can be extended to nominal predicative uses given that the differences between these processes are tangential to the core analysis.

Thanks to Alex Kocurek for this example.

Interestingly, the concessive meaning of though in Present-Day English is thought to have evolved from a conditional even if-like meaning that was in use as late as Early Modern English (König and Siemund, 2000).

We need to use the counterpart relation C here because topic situations are world-bound, and, as Schwarz discusses, speakers are not omniscient but often only privy to a relevant subset of properties of the topic situation.

References

Anand, P., & Hacquard, V. (2008). Epistemics with attitude. In T. Friedman, & S. Ito (Eds.), Proceedings of SALT (Vol. 18, pp. 37–54).

Arregui, A., Rivero, M. L., & Salanova, A. (2014). Cross-linguistic variation in imperfectivity. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 32(2), 307–362.

Asher, N., & Morreau, M. (1991). Commonsense entailment: A modal theory of nonmonotonic reasoning. In J. Mylopoulos, & R. Reiter (Eds.), Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (pp. 387–392). San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

Asudeh, A. (2002). Richard III. In M. Andronis, E. Debenport, A. Pycha, & K. Yoshimura (Eds.), CLS 38: The main session (pp. 31–46). Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Asudeh, A. (2004). Resumption as resource management. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University.

Asudeh, A., & Toivonen, I. (2007). Copy raising and its consequences for perceptual reports. In A. Zaenen, J. Simpson, T. H. King, J. Grimshaw, J. Maling, & C. Manning (Eds.), Architectures, rules, and preferences: Variations on themes by Joan W. Bresnan (pp. 49–67). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Asudeh, A., & Toivonen, I. (2012). Copy raising and perception. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 30(2), 321–380.

Austin, J. L. (1950). Truth. Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume, 24, 111–129.

Bach, E. (1981). On time, tense, and aspect: An essay in English metaphysics. In P. Cole (Ed.), Radical pragmatics (pp. 62–81). New York: Academic Press.

Barwise, J. (1989). The situation in logic. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Barwise, J., & Etchemendy, J. (1987). The liar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beck, S., & von Stechow, A. (2015). Events, times, and worlds—An LF architecture. In C. Fortmann & I. Rapp (Eds.), Situationsargumente im Nominalbereich (pp. 13–46). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bender, E., & Flickinger, D. (1999). Diachronic evidence for extended argument structure. In G. Bouma, E. Hinrichs, G.-J. Kruijff, & R. Oehrle (Eds.), Constraints and resources in natural language syntax and semantics (pp. 3–19). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Bledin, J., & Rawlins, K. (2019). What Ifs. Semantics & Pragmatics, 12(14), 1–55.

Bledin, J., & Srinivas, S. (2019). As Ifs. In M. T. Espinal, E. Castroviejo, M. Leonetti, & L. McNally (Eds.), Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung (Vol. 23, pp. 167–184).

Breckenridge, W. (2007). The meaning of “look”. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oxford.

Breckenridge, W. (2018). Visual experience: A semantic approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brewer, B. (2006). Perception and content. European Journal of Philosophy, 14(2), 165–181.

Brinton, L. J. (2014). The extremes of insubordination: Exclamatory as if! Journal of English Linguistics, 42(2), 93–113.

Brogaard, B. (2012). What do we say when we say how or what we feel? Philosophers’ Imprint, 12(11), 1–22.

Brogaard, B. (2014). Does perception have content? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brook, M. (2014). Comparative complementizers in Canadian English: Insights from early fiction. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 20(2), 1–10.

Bücking, S. (2017). Composing wie wenn—The semantics of hypothetical comparison clauses in German. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 35(4), 979–1025.

Büring, D. (2003). On D-trees, beans, and B-accents. Linguistics and Philosophy, 26(5), 511–545.

Byrne, A. (2009). Experience and content. Philosophical Quarterly, 59(236), 429–451.

Camp, E. (2012). Sarcastic, pretense, and the semantics/pragmatics distinction. Noûs, 46(4), 587–634.

Camp, E., & Hawthorne, J. (2008). Sarcastic ‘like’: A case study in the interface of syntax and semantics. Philosophical Perspectives, 22(1), 1–21.

Carlson, G. N. (1984). Thematic roles and their role in semantic interpretation. Linguistics, 22(3), 259–279.

Chierchia, G. (1995). Individual-level predicates as inherent generics. In G. N. Carlson, & F. J. Pelletier (Eds.), The generic book (pp. 176–223). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chisholm, R. (1957). Perceiving: A philosophical study. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Ciardelli, I. (2016). Lifting conditionals to inquisitive semantics. In M. Moroney, C.-R. Little, J. Collard, & D. Burgdorf (Eds.), Proceedings of SALT (Vol. 26, pp. 732–752).

Cipria, A., & Roberts, C. (2000). Spanish imperfecto and pretérito: Truth conditions and aktionsart effects in a situation semantics. Natural Language Semantics, 8(4), 297–347.

Condoravdi, C., & Lauer, S. (2012). Imperatives: Meaning and illocutionary force. In C. Piñón (Eds.), Empirical issues in syntax and semantics (Vol. 9, pp. 37–58). Paris: CSSP.

Davidson, D. (1967). The logical form of action sentences. In N. Rescher (Ed.), The logic of decision and action (pp. 81–95). Pitttsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Davidson, D. (1969). The individuation of events. In N. Rescher (Ed.), Essays in honor of Carl G. Hempel: A tribute on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday (pp. 216–234). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Davies, M. (2008). Corpus of American English: 360 million words, 1990-present. http://www.americancorpus.org.

Ellis, B., Jackson, F., & Pargetter, R. (1977). An objection to possible-world semantics for counterfactual logics. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 6(1), 355–357.

Gärdenfors, P. (2000). Conceptual spaces: The geometry of thought. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Giannakidou, A., & Quer, J. (2013). Exhaustive and non-exhaustive variation with free choice and referential vagueness: Evidence from Greek, Catalan, and Spanish. Lingua, 126(1), 120–149.

Gillies, A. (2007). Counterfactual scorekeeping. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(3), 329–360.

Ginzburg, J. (1996). Dynamics and the semantics of dialogue. In J. Seligman & D. Westerståhl (Eds.), Logic, language, and computation, Vol. 1 (pp. 221–237). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Glüer, K. (2017). Talking about looks. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 8(4), 781–807.

Goodman, N. (1947). The problem of counterfactual conditionals. Journal of Philosophy, 44(5), 113–128.

Hacquard, V. (2006). Aspects of modality. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Hacquard, V. (2010). On the event relativity of modal auxiliaries. Natural Language Semantics, 18(1), 79–114.

Heim, I. (1983). On the projection problem for presuppositions. In M. Barlow, D. Flickinger, & M. Wescoat (Eds.), WCCFL 2: Second Annual West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (pp. 114–125). Stanford: Stanford University.

Heim, I., & Kratzer, A. (1998). Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Hintikka, J. (1962). Knowledge and belief: An introduction to the logic of the two notions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Huddleston, R., & Pullum, G. K. (2002). The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Iatridou, S. (2000). The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry, 31(2), 231–270.

Jackson, F. (1977). Perception. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kasper, W. (1987). Semantik des Konjunktivs II in Deklarativsätzen des Deutschen. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Kaufmann, M. (2012). Interpreting imperatives. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kennedy, C. (1999). Projecting the adjective: The syntax and semantics of gradability and comparison. New York: Garland.

Klein, W. (1994). Time in Language. London: Routledge.

König, E., & Siemund, P. (2000). Causal and concessive clauses: Formal and semantic relations. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & B. Kortmann (Eds.), Cause—Condition—Concession—Contrast. Cognitive and discourse perspectives (pp. 341–360). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1977). What ‘must’ and ‘can’ must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1(3), 337–355.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H.-J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts (pp. 38–74). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1986). Conditionals. In A. M. Farley, P. Farley, & K. E. McCollough (Eds.), Papers from the Parasession on Pragmatics and Grammatical Theory (pp. 115–135). Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Kratzer, A. (1989). An investigation of the lumps of thought. Linguistics and Philosophy, 12(5), 607–653.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow, & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research (pp. 639–650). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1995). Stage-level and individual-level predicates. In G. N. Carlson, & F. J. Pelletier (Eds.), The generic book (pp. 125–175). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kratzer, A. (1996). Severing the external argument from its verb. In J. Rooryck, & L. Zaring (Eds.), Phrase structure and the lexicon (pp. 109–137). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kratzer, A. (1998). More structural analogies between pronouns and tense. In D. Strolovitch, & A. Lawson (Eds). Proceedings of SALT, (Vol. 8, pp. 92–110).

Kratzer, A. (2002). Facts: Particulars or information units. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25(5–6), 655–670.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Modals and conditionals: New and revised perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kratzer, A. (2020). Situations in natural language semantics. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Fall edition. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/situations-semantics/.

Kratzer, A. (2006). Decomposing attitude verbs. Talk given in honor of Anita Mittwoch, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Krifka, M. (1989). Nominal reference, temporal constitution and quantification in event semantics. In R. Bartsch, J. van Benthem, & P. van Emde Boas (Eds.), Semantics and contextual expressions (pp. 75–115). Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Krifka, M. (1992). Thematic relations as links between nominal reference and temporal constitution. In I. A. Sag & A. Szabolcsi (Eds.), Lexical matters (pp. 29–53). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Landau, I. (2011). Predication vs. aboutness in copy raising. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 29(3), 779–813.

Landman, F. (2000). Events and plurality: The Jerusalem lectures. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Landman, M., & Morzycki, M. (2003). Event-kinds and the representation of manner. In N. M. Antrim, G. Goodall, M. Schulte-Nafeh, & V. Samiian (Eds.), Proceedings of the Western Conference in Linguistics (WECOL) 2002 (pp. 136–147). Fresno: California State University.

Lassiter, D. (2018). Complex sentential operators refute unrestricted simplification of disjunctive antecedents. Semantics and Pragmatics, 11(9).

Lewis, D. (1968). Counterpart theory and quantified modal logic. Journal of Philosophy, 65(5), 113–126.

Lewis, D. (1973). Counterfactuals. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1975). Adverbs of quantification. In E. L. Keenan (Ed.), Semantics of natural language (pp. 3–15). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. (1979). Counterfactual dependence and time’s arrow. Noûs, 13(4), 455–476.

Lewis, D. (1986). On the plurality of worlds. Oxford: Blackwell.

López-Couso, M. J., & Méndez-Naya, B. (2012a). On the use of as if, as though, and like in present-day English complementation structures. Journal of English Linguistics, 40(2), 172–195.

López-Couso, M. J., & Méndez-Naya, B. (2012b). On comparative complementizers in English: Evidence of historical English corpora. In N. Vázquez-González (Ed.), Creation and use of English Corpora in Spain (pp. 309–333). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

Maienborn, C. (2001). On the position and interpretation of locative modifiers. Natural Language Semantics, 9(2), 191–240.

Martin, M. G. F. (2010). What’s in a look? In B. Nanay (Ed.), Perceiving the world (pp. 160–225). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Matushansky, O. (2002). Tipping the scales: The syntax of scalarity in the complement of seem. Syntax, 5(3), 219–276.

McDonnell, N. (2016). Events and their counterparts. Philosophical Studies, 173(5), 1291–1308.

Moltmann, F. (2017). Cognitive products and the semantics of attitude verbs and deontic modals. In F. Moltmann & M. Textor (Eds.), Act-based conceptions of propositional content (pp. 254–290). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moulton, K. (2009). Natural selection and the syntax of clausal complementation. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Moulton, K. (2015). CPs: Copies and compositionality. Linguistic Inquiry, 46(2), 305–342.

Nute, D. (1975). Counterfactuals and the similarity of worlds. Journal of Philosophy, 72(21), 773–778.

Parsons, T. (1990). Events in the semantics of English: A study in subatomic semantics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Partee, B. (1973). Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns. Journal of Philosophy, 70(18), 601–609.

Postal, P. (1974). On raising. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Potsdam, E., & Runner, J. T. (2001). Richard returns: Copy raising and its implications. In M. Andronis, C. Ball, H. Elston, & S. Neuvel (Eds.), CLS 37: The Main Session (pp. 453–468). Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Ramchand, G. (2014). Stativity and present tense epistemics. In T. Snider, S. D’Antonio, & M. Weigand (Eds.), Proceedings of SALT (Vol. 24, pp. 102–121).

Rawlins, K. (2008). (Un)conditionals: An investigation in the syntax and semantics of conditional structures. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Rawlins, K. (2013a). (Un)conditionals. Natural Language Semantics, 21(2), 111–178.

Rawlins, K. (2013b) About ‘about’. In T. Snider (Ed.), Proceedings of SALT (Vol. 23, pp. 336–357).

Renans, A. (2021). Definite descriptions of events: Progressive interpretation in Ga (Kwa). Linguistics and Philosophy, 44(2), 237–279.

Roberts, C. (1996). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. In J. H. Yoon & A. Kathol (Eds.), Papers in semantics (Working Papers in Linguistics 49) (pp. 91–136). Columbus: Ohio State University.

Roberts, C. (2012). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics & Pragmatics, 5(6), 1–69.

Schaffer, J. (2005). Contrastive causation. Philosophical Review, 114(3), 327–358.

Schellenberg, S. (2011). Perceptual content defended. Noûs, 45(4), 714–750.

Schulz, K. (2014). Fake tense in conditional sentences: A modal approach. Natural Language Semantics, 22(2), 117–144.

Schwarz, F. (2009). Two types of definites in natural language. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst .

Siegel, S. (2010). The contents of visual experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Siegel, S., & Byrne, A. (2017). Rich or thin? In B. Nanay (Ed.), Current controversies in the philosophy of perception (pp. 59–80). London: Routledge.

Stalnaker, R. (1980). A defense of conditional excluded middle. In W. Harper, R. Stalnaker, & G. Pearce (Eds.), Ifs (pp. 87–104). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Stalnaker, R. (1984). Inquiry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stanley, J., & Williamson, T. (2001). Knowing how. Journal of Philosophy, 98(8), 411–444.

Starr, W. (2014). A uniform theory of conditionals. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 43, 1019–1064.

Travis, C. (2004). The silence of the senses. Mind, 113(449), 57–94.

Travis, C. (2013). Susanna Siegel, The contents of visual experience. Philosophical Studies, 163(3), 837–846.

Umbach, C., & Gust, H. (2014). Similarity demonstratives. Lingua, 149, 74–93.

van Kuppevelt, J. (1996). Inferring from topics: Scalar implicatures as topic-dependent inferences. Linguistics and Philosophy, 19(4), 393–443.

Veltman, F. (1996). Defaults in update semantics. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 25(3), 221–261.

von Fintel. K. (1994). Restrictions on quantifier domains. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Willer, M. (2015). Simplifying counterfactuals. In T. Brochhagen, F. Roelofsen, & N. Theiler (Eds.), Proceedings of the 20th Amsterdam Colloquium (pp. 428–437). Amsterdam: ILLC.

Zobel, S. (2016). Adjectival As-phrases as intensional secondary predicates. In M. Moroney, C.-R. Little, J. Collard, & D. Burgdorf (Eds.), Proceedings of SALT, (Vol. 26, pp. 284–303).

Zobel, S. (2018). An analysis of the semantic variability of weak adjuncts and its problems. In U. Sauerland, & S. Solt (Eds.), Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung (Vol. 22, pp. 499–516).

Zobel, S. (2019). Accounting for the “causal link” between free adjuncts and their host clauses. In M. T. Espinal, E. Castroviejo, M. Leonetti, & L. McNally (Eds.), Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung (Vol. 23, pp. 489–506).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

First and foremost, we are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers at L &P as well as the editor, Ashwini Deo, for their extensive engagement with this paper. We are also especially grateful to Sebastian Bücking and Sarah Zobel not only for providing thoughtful suggestions at various stages of our project, but also for their own work on hypothetical comparative constructions that have greatly influenced our ideas. This paper has benefited from the input of Ana Arregui, Maria Biezma, Sam Carter, Lucas Champollion, Simon Charlow, Alexander Göbel, Simon Goldstein, Steven Gross, Daniel Harris, Michael Johnson, Alex Kocurek, Friederike Moltmann, Kyle Rawlins, Jessica Rett, Matthew Ritchie, Rachel Rudolph, Paolo Santorio, Boaz Schuman, and Simon Wimmer, our thanks to them all. Our work on As Ifs was presented in 2018 at Hong Kong University, SuB 23, and the New York Philosophy of Language Workshop, and in 2019 at SuB 24, the Central APA, the Ontario Meaning Workshop, PhLiP 6, and the Workshop on Clausal Complements and Sentence-Embedding Predicates at NYU. We thank the reviewers and audiences at these conferences for helpful discussion.

Appendix: More compositional details

Appendix: More compositional details

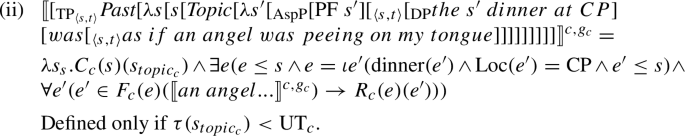

In this appendix, we provide a more complete semantic interpretation of the manner use (51) and lay out the ingredients needed to analyze the other examples discussed throughout the paper.

Along with the contextual parameters introduced for our hypothetical comparative semantics for as if, we assume that context supplies an assignment function \(g_{c}\) for evaluating referential pronouns like he in the as if-phrase (Heim and Kratzer, 1998), which is interpreted as a free variable that co-refers with Pedro:

As mentioned in Sect. 3.5, eventualities are introduced by a neo-Davidsonian lexical semantics (Carlson, 1984; Parsons, 1990; Krifka, 1992; among others), where verbs denote properties of eventualities:Footnote 47

These eventualities are linked to their participants via thematic roles (functions of type \(\langle s, e \rangle \), such as Agent and Theme), which are introduced by syntactic correlates in LF (Kratzer, 1996):

Higher up in the clausal hierarchy above the VP-layer is the aspectual layer where a perfective or imperfective operator existentially binds the eventuality argument and takes us from eventualities to larger situations by situating an eventuality with respect to a situation parameter s that can later be saturated with a topic/reference situation supplied by tense. For perfective aspect, we use the following situational variant of Beck and von Stechow’s (2015) perfective operator that locates an eventuality within its situation argument:

Our more complicated imperfectivity operator IMPF is based on the proposal in Arregui et al. (2014) (who build on Cipria and Roberts, 2000), which involves a contextually or linguistically determined accessibility relation \({\mathcal {R}}_{\langle s, \langle s, t \rangle \rangle }\) whose range of interpretations correspond to temporal, generic, and modal flavors of imperfectivity—in example (51), think of \({\mathcal {R}}\) as returning time-slices of the situation parameter s, which will help ensure that Pedro was possessed by demons at the time of his dancing:

Higher still in the clausal hierarchy is tense, which is given a referential analysis (Partee, 1973; Kratzer, 1998; Hacquard, 2006). In particular, we assume that the tense layer above aspect contributes one of the situational pronouns in (169), where Present and Past both refer to the topic situation \(s_{topic_{c}}\) and carry the presupposition that its ‘runtime’ \(\tau (s_{topic_{c}})\) (Krifka, 1989) overlaps with or precedes the utterance time UT\(_{c}\) respectively, and the zero tense \(\varnothing _{s}\) allows us to implement Kratzer’s (1998) analysis of ‘sequence of tense’:

Note that feeding a proposition returned by aspect directly into tense would return a truth value of type t rather than a proposition of type \(\langle s, t \rangle \) as desired. To ensure that the final output of the compositional machinery is propositional, we follow Schwarz (2009) in assuming that a Topic operator mediates between the aspectual and tense layers (the integration of Topic with the situational treatment of tenses builds on an earlier version of Kratzer, 2012; see also Ramchand, 2014):Footnote 48

Lastly, we need our as if entry (74), which is restated below:

Applying these semantic ingredients, we interpret the prejacent of the as if-phrase in (51) as follows:

Feeding this proposition into the as if entry (171) delivers the following property of situations:

Assuming that the matrix tense Past is raised in order to bind the zero tense in the as if complement, (51) is fully interpreted as follows:

Using these same compositional ingredients, we can also interpret the perceptual resemblance report (87) as follows (only the hypothetical comparative analysis from Sect. 4.2 is spelled out in more detail, though it should be clear how the propositional attitude-like analysis from Sect. 4.1 would proceed):

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bledin, J., Srinivas, S. Descriptive As Ifs. Linguist and Philos 46, 87–134 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-022-09352-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-022-09352-3