Abstract

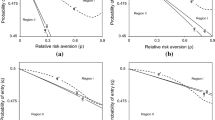

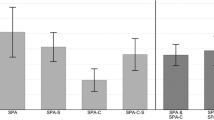

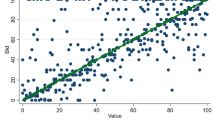

In this paper, we run a laboratory experiment to compare two mechanisms in a procurement setting: Right-of-First-Refusal (ROFR) where the incumbent supplier is granted a privileged position versus standard First-Price-Auction (FPA). To this end, we have subjects compete against a computerized agent programmed to behave in a risk-neutral way (i) in a FPA, and (ii) in a ROFR auction where the “incumbent” bidder is the computer. In contrast with theory, we observe that on average bidders are slightly but significantly more aggressive under the ROFR when their costs are such that they are predicted to behave identically under both auction procedures. For the sub-sample of subjects for whom we can estimate a CRRA parameter, we confirm the theoretical prediction that the buyer’s expected cost is larger in the ROFR if the newcomer is not sufficiently risk-averse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unless otherwise stated, tests are two-sided.

The equality of matched pairs of observations can be tested by using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test (see e.g. Siegel and Castellan 1988). This is done by computing the differences between each matched-pair (here, we compute every subject’s average bid in the ROFR minus his average bid in the FPA), order the differences, calculate the sum of the ranks for all positive and all negative differences and compare them to the expected sums if both distributions had been the same. A simpler version is to focus only on the proportion of positive (negative) signs, which amounts in testing only whether the median of the differences is zero. This is done using a binomial test. In this article, we only present the former test, but we also checked the result of the latter.

In practice, subject could bid 149.5 to be perfectly sure to win the market.

This means that this subject tends to submit bids larger than a risk-neutral subject. We shall test the robustness of all of our results by omitting this subject.

But we verified that a Tobit regression provides similar results.

Since the two estimators \(\hat{{\alpha }}\) and \(\hat{{\beta }}\) are dependent random variables, it would not be correct to test Prediction 1 by using the two separate tests \(\alpha =0\) and \(\beta =1\).

But we also tolerate a few errors for 3 subjects.

Again, this result is not affected by any significant order effect: exactly 10/48 subjects match the theoretical prediction in order 1 and order 2.

This result is robust to the order of treatments within sessions (we carried out the same regression for each order separately) and to learning (we carried out the same regression suppressing the first 4, 8, and 12 periods).

References

Arozamena, L., & Weinschelbaum, F. (2009). The effect of corruption on bidding behavior in first-price auctions. European Economic Review, 53, 645–657.

Bikhchandani, S., Lippman, S. A., & Reade, R. (2005). “On the Right-of-First-Refusal”. Advances in Theoretical Economics, 5(1), 1–42.

Brisset, K., & Maréchal, F. (2014). Right of first refusal versus first-price auction with heterogeneous risk-averse bidders. Besançon: University of Franche-Comté.

Burguet, R., & Perry, M. (2009). Preferred suppliers in auction markets. Rand Journal of Economics, 40(2), 283–295. Rand Corporation.

Choi, A. (2005). A rent extraction theory of the right-of-first-refusal. Journal of Industrial Economics, 57(2), 252–262.

Chouinard, H. (2009). Auctions with and without the right of first refusal and national park service concession contracts. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87, 1082–1087.

Cox, J., Roberson, B., & Smith, V. L. (1982). Theory and behavior of single object auction. Research in Experimental economics, 2, 1–43.

Elmaghraby, W., Goyal, W., & Pilehvar, A. (2013). “Right-of-First-Refusal in sequential procurement auctions”. mimeo.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. The American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Lee, J. S. (2008). Favoritism in asymmetric procurement auctions. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 26, 1407–1424.

Porter, R., & Shoham, Y. (2004). On cheating in sealed-bid auctions. Journal of Decision Support Systems, 39, 41–54.

Siegel, S., & Castellan, N. J. (1988). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: MacGraw-Hill.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2011). Contest design: An experimental investigation. Economic Inquiry, 49, 573–590.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants at ASFEE’s conference (May 2012), in particular R. Préget and R. Vranceanu, for helpful comments. We are also grateful to Ron Harstad for his advice concerning the protocol. The financial support of the University of Franche-Comté is greatly acknowledged. This experiment was run in the laboratory of the University of Strasbourg (LEES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

1.1 Instructions of the experiment for a FPA–ROFR session (translation in English)

\(\mathbf{1}{\mathbf{st}}\) Part

Welcome

This experiment aims at investigating economic behavior. Please read the following instructions carefully. Once you have finished reading the instructions, we will ask you to answer a questionnaire testing your understanding of the rules of this experiment.

A computer will process all your answers anonymously. Depending on your decisions, you can earn a significant amount of money, which will be paid to you in cash at the end of the experiment.

Please ask for assistance by putting your hand up if at any moment there is something that you do not understand. Please do not communicate among each other during the experiment.

How to make money?

You are the vendor of a product. To make money, you sell this product to a buyer. You are competing against another vendor whose role is played by the computer.

At the beginning of each period, you are assigned an individual cost (in tokens) for the product that you sell. This cost is a natural number selected at random in the set {100; 101; 102; ..., 199; 200}. Each value in this set has the same chances of being drawn.

The winner is the one who submits the lowest bid. Be careful: the accepted maximum bid is 200 included. The experiment has 28 periods, the first three being trial periods. At each period, the procedure is as follows: You and your competitor (the computer) submit simultaneously one bid.

-

If your bid is the lowest one, you win the auction. Your gain = your bid \(-\) your cost.

-

If your competitor submits the lowest bid, you win nothing.

-

If bids are equal, the winner is selected at random using a mechanism like a “coin flip”.

Bids can be expressed with a decimal of 0.5.

At each period, your competitor’s bid is a random number between 150 and 200 tokens with an increment of 0.5 (150; 150,5;....; 199; 199,5; 200). Each value has the same chance of being drawn. Your cost and your competitor’s bid are selected at random in completely independent drawings. “Independent” means that it is as if the values were determined by the throw of dices.

The auction’s result will be announced at the end of each period.

Your payment:

You will get a show-up fee of 5 euros. In addition, you will earn the sum of your payoffs in 12 periods drawn at random, applying a conversion rate of 1 token = 6 cents.

***

\(\mathbf{2}{\mathbf{nd}}\) Part

The second experience has 28 periods with three test periods too. Again, you are in competition with another vendor whose role is performed by the computer.

At the beginning of each period, an individual cost for the product is assigned to each vendor (you and the computer). Each cost is a natural number drawn number selected at random in the set {100; 101; 102; ..., 199; 200}. Each value between these two numbers has the same chance of being drawn. Your cost and the computer’s cost are completely independent. “Independent” means that it is as if the values were determined by the throw of dices.

The purchase process is modified and takes place in two stages:

-

Stage 1: You will be asked to submit a bid to the buyer.

-

Stage 2: The buyer then proposes this bid to the other vendor, the computer, who has the opportunity to match or not on it. The computer makes a decision to maximize its profit. So he accepts the sale if the proposed bid is greater than or equal to his cost.

-

If he accepts, he wins the sale at a price equal to this bid. Your gain is 0.

-

Otherwise, the sale is won by yourself at this price and your gain is: your bid \(-\) your cost.

-

Again, the accepted maximum bid is 200 tokens included. Bids can be expressed with an increment of 0.5.

Your payment:

At the end of 25 periods, your payment will be the sum of the gains made by taking at random 12 of the 25 periods.

The conversion is as follows: 1 token = 6 cents.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brisset, K., Cochard, F. & Maréchal, F. Is the newcomer more aggressive when the incumbent is granted a Right-of-First-Refusal in a procurement auction? Experimental Evidence. Theory Decis 78, 639–665 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-014-9438-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-014-9438-z