Abstract

Banks play a unique role in society. They not only maximize profits but also consider the interests of stakeholders. We investigate whether banks consider firms’ pollution records in their lending decisions. The evidence shows that banks offer significantly higher loan spreads, higher total borrowing costs, shorter loan maturities, and greater collateral to firms with higher levels of chemical pollution. The costly effects are stronger for borrowers with greater risk and weaker corporate governance. Further, the results show that banks with higher social responsibility account for their borrowers’ environmental performance and charge higher loan spreads to those with poor performance. These results support the idea that banks with higher social responsibility can promote the practice of business ethics in firms.

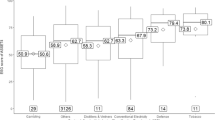

Source Plotted using latest data from the US Environmental Protection Agency

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to Scholtens (2009), every eight dollars invested is subject to social or ethical screening. In many OECD countries, banks offer savings accounts to the public while promising that the funds are being used for environmentally sound projects.

Proposed by the World Bank in 2002, the Equator Principles represent a risk-management framework that provides a minimum standard for due diligence and monitoring to support responsible risk decisions. To date, 97 financial institutions in 37 countries that cover more than 70% of the global lending volume in emerging markets have adopted the Equator Principles (Gupta 2018).

The main argument behind these studies is that firms should consider the interest of a broader group of stakeholders, such as customers, employees, creditors, and other concerned members of their community.

Prior studies on the corporate bond spread or credit rating as a proxy for the cost of debt have not been able to highlight the role of banks in valuing a company’s environmental policy.

The KLD score considers broad dimensions of how a company behaves in society and is often viewed as a general score of corporate social responsibility. KLD data come from surveys, financial statement information, media reports, government documents, and other legal journals to rank companies on 13 dimensions of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Therefore, the score of KLD can be viewed as an indirect measure of corporate environmental performance.

Trucost contains data about a broad range of corporate social and environmental performances. The variables cover the amount of emissions, waste production, water abstractions, natural resource use, and raw material extraction. The data span from 2004 through 2008 and comprise a sample of 1,200 publicly traded firms in the US (Delmas et al. 2015). Although it covers a wide range of variables, the data period is limited.

The KLD database only typically covers large listed companies in the US and does not cover all firms that report data to TRI. Thus, about 3,890 observations, or 46.35% of our TRI data sample, are contained in the KLD database.

For example, Herbohn, Gao, and Clarkson (2019) investigate whether banks consider carbon risk in their lending decisions and find positive and significant excess announcement-period returns for loan-renewal announcements for high-risk carbon firms that involve favorable revisions to the loan terms. Du et al. (2017) use hand-collected data on corporate environmental performance and a sample of privately-owned Chinese firms to show that the interest rate of on debt is significantly and negatively associated with their environmental performance.

In this related literature, El Ghoul et al. (2019) also examine the role of the media in corporate social responsibility. Bhojraj and Sengupta (2003) indicate that firms with greater institutional ownership and more outside directors on the board benefit from better monitoring, and in turn they enjoy lower bond yields and higher credit ratings on their public debt.

For example, they may choose to invest in risky but potentially high-return projects (Jensen and Meckling 1976), or underinvest in positive NPV projects to grab more benefits from the firm, particularly when they are under takeover threats or financial difficulties.

Cremers et al. (2007) find that the bond spread increases when the firm has stronger control over shareholders and face a high vulnerability for takeover. They explain this phenomenon as the bondholders’ concern about the possible future default risk for those firms that may engage in mergers and acquisitions, and then add more debt to the firm.

In the United States, chemicals in household products alone cost a staggering $340 billion a year in healthcare expenditures and lost earnings (Attina et al. 2016). The primary legal institution tasked with reviewing and regulating chemicals is the EPA, which has been overburdened since its inception in 1976. In an attempt to augment the EPA’s power, former President Barack Obama signed the Frank Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act before leaving office in 2016, thus updating the Toxic Substances Control Act. The new law received overwhelming and rarely seen bipartisan support in both the US House of Representatives and the Senate. The Act requires more effort in disclosing information on toxic chemical emissions and making them accessible to the public via the TRI database.

It is the percentile ranking of a firm’s default risk based on its distance to default drawn from Bharath and Shumway (2008).

In our study, given that the average loan spread of the sample firms is 169.84 bp, a one-standard-deviation increase in chemical emissions (CE) is associated with a 6.7169 bp (\({\text{e}}^{0.7020} \times { }\) 0.0196 \(\times\) 169.84 = 6.7169) increase in the loan spread. As the average loan size is $186.98 (\({\text{e}}^{5.2310} = { }\) 186.98) million and the average loan time to maturity is 3.2204 (\({\text{e}}^{3.6544} /\) 12 = 3.2204) years, a one-standard-deviation increase in chemical emissions leads to an average increase of $0.4045 million (6.7169 bp \(\times\) 186.98 \({ } \times\) 3.2204) in interest payments.

Note that there may be differences across the locations where the firms are headquartered. Further, the environmental policies of polluting counties (cities) should be more relevant to the firms’ operation than the policies of headquarter counties. This difference also applies to cross-border investments, as some firms in our sample have headquarters outside the United States.

We construct similar IVs using official US zip code data. Alternatively, we use the total chemical emissions instead of total chemical emissions to net income as the base variable to construct the IVs. Using these IVs does not substantially change our estimates.

Unreported tests of weak instruments using the Cragg-Donald F-statistic (Cragg and Donald 1993) and underidentification (using the Anderson canonical correlation LM statistic (Anderson 1951) indicate that our instrument is not weak and our specification is not underidentified. The results are available on request.

It is very important to stress that we only consider the selection bias due to observables and use propensity score matching to account for it. This approach is not designed to address the self-selection bias due to unobservables (Tucker 2010; Park and Shin 2020). Unobservable factor-related biases can be remedied by the 2SLS approach and by incorporating firm fixed effects.

To confirm the parallel-trends assumption for the PSM estimator, we examine the univariate comparisons between treatment and control firms’ characteristics used in the matching process. Unreported results show that none of the observed differences is statistically significant. This preliminary diagnostic test provides some evidence that differences in loan spreads are caused primarily by differences in the level of chemical emissions.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this analysis.

CSR strength (concern) is the sum of the ratios of the number of CSR strengths (concerns) of firm i to the total number of strength indicators across the seven rating dimensions in the KLD dataset.

We thank an anonymous referee for making this suggestion.

In here, Pvote is the percentage of voters who voted in presidential elections, Respn is the response rate to the Census Bureau’s decennial census, Nccs is the number of tax-exempt non-profit organizations per 10,000 people, and Assn is the number of social organizations per 100,000 people.

References

Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. W. (2011). Bias-corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 29, 1–11.

Agarwal, S., & Hauswald, R. (2010). Distance and private information in lending. The Review of Financial Studies, 23, 2757–2788.

Anderson, T. W. (1951). Estimating linear restrictions on regression coefficients for multivariate normal distributions. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 22, 327–351.

Attig, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Suh, J. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and credit ratings. Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 679–694.

Attina, T. M., Hauser, R., Sathyanarayana, S., Hunt, P. A., Bourguignon, J. P., Myers, J. P., et al. (2016). Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the USA: a population-based disease burden and cost analysis. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, 4, 996–1003.

Balkenborg, D. (2001). How liable should a lender be? The case of judgment-proof firms and environmental risk: Comment. American Economic Review, 91, 731–738.

Beasley, M. S. (1996). An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director composition and financial statement fraud. Accounting review, 71, 443–465.

Berg, T., Saunders, A., & Steffen, S. (2016). The total cost of corporate borrowing in the loan market: Don't ignore the fees. Journal of Finance, 71, 1357–1392.

Berger, A. N., & Hannan, T. H. (1998). The efficiency cost of market power in the banking industry: A test of the “quiet life” and related hypotheses. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 454–465.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55, 82–113.

Bharath, S., & Shumway, T. (2008). Forecasting default with the Merton distance to default model. Review of Financial Studies, 21, 1339–1369.

Bharath, S. T., Sunder, J., & Sunder, S. V. (2008). Accounting quality and debt contracting. Accounting Review, 83, 1–28.

Bhojraj, S., & Sengupta, P. (2003). Effect of corporate governance on bond ratings and yields: The role of institutional investors and outside directors. The Journal of Business, 76, 455–475.

Boytsun, A., Deloof, M., & Matthyssens, P. (2011). Social norms, social cohesion, and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 19, 41–60.

Bui, D. G., Chen, Y. S., Hasan, I., & Lin, C. Y. (2018). Can Lenders discern managerial ability from luck? Evidence from Bank Loan Contracts. Journal of Banking and Finance, 87, 187–201.

Campbell, J. Y., & Taksler, G. B. (2003). Equity Volatility and Corporate Bond Yields. Journal of Finance, 58, 2321–2350.

Chan, M., Lin, C., & Lin, T. (2020). Wisdom of crowds before 2007–2009 global financial crisis. Journal of Financial Stability, 48, 100741.

Chava, S. (2014). Environmental externalities and cost of capital. Management Science, 60, 2223–2247.

Cheung, Y. L., Tan, W., & Wang, W. (2018). National stakeholder orientation, corporate social responsibility, and bank loan cost. Journal of Business Ethics, 150, 505–524.

Cogan, D. G. (2008). Corporate governance and climate change: The banking sector, a Ceres Report by RiskMetrics Group.

Coulson, A. B., & Monks, V. (1999). Corporate environmental performance considerations within bank lending decisions. Corporate Social-Responsibility and Environmental Management, 6, 1–10.

Cragg, J. G., & Donald, S. G. (1993). Testing identifiability and specification in instrumental variable models. Econometric Theory, 9, 222–240.

Cremers, K. M., Nair, V. B., & Wei, C. (2007). Governance mechanisms and bond prices. The Review of Financial Studies, 20, 1359–1388.

Davis, P., & Worthington, S. (1993). Cooperative values: Change and continuity in capital accumulation the case of the British Cooperative Bank. Journal of Business Ethics, 12, 849–859.

De la Cuesta-González, M., Muñoz-Torres, M. J., & Fernández-Izquierdo, M. Á. (2006). Analysis of social performance in the Spanish financial industry through public data. A proposal. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 289–304.

Delmas, M. A., Nairn-Birch, N., & Lim, J. (2015). Dynamics of environmental and financial performance: The case of greenhouse gas emissions. Organization & Environment, 28, 374–393.

Denis, D. J., & Mihov, V. T. (2003). The choice among bank debt, non-bank private debt, and public debt: evidence from new corporate borrowings. Journal of Financial Economics, 70, 3–28.

Diamond, D. W. (1984). Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. The Review of Economic Studies, 51, 393–414.

Doa, M. J. (1992). The toxics release inventory. Hazardous Waste and Hazardous Materials, 9, 61–72.

Du, X., Weng, J., Zeng, Q., Chang, Y., & Pei, H. (2017). Do lenders applaud corporate environmental performance? Evidence from Chinese private-owned Firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 143, 179–207.

Easley, D., & O’hara, M. (2004). Information and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 59, 1553–1583.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kim, H., & Park, K. (2018). Corporate environmental responsibility and the cost of capital: International evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 149, 335–361.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Nash, R., & Patel, A. (2019). New evidence on the role of the media in corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 154, 1051–1079.

Elster, J. (1989). Social norms and economic theory. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3, 99–117.

EPA. (2015). United StatesEnvironmental ProtectionAgency: Consolidated List of Chemicals. Office of Solid Wasteand Emergency Response. Paper EPA 550-B-15-001.

Francis, B., Hasan, I., Koetter, M., & Wu, Q. (2012). Corporate boards and bank loan contracting. Journal of Financial Research, 35, 521–552.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Gao, H., Li, K., & Ma, Y. (2017). Stakeholder orientation and the cost of debt: Evidence from a natural experiment. Available at SSRN 2878415.

Ge, W., Kim, J. B., & Song, B. Y. (2012). Internal governance, legal institutions and bank loan contracting around the world. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18, 413–432.

Goss, A., & Roberts, G. S. (2011). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Banking and Finance, 35, 1794–1810.

Graham, J. R., Li, S., & Qiu, J. (2008). Corporate misreporting and bank loan contracting. Journal of Financial Economics, 89, 44–61.

Gupta, K. (2018). Environmental sustainability and implied cost of equity: International evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 147, 343–365.

Hasan, I., Hoi, C. K. S., Wu, Q., & Zhang, H. (2014). Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Financial Economics, 113, 109–130.

Hasan, I., Hoi, C. K., Wu, Q., & Zhang, H. (2017). Social capital and debt contracting: Evidence from bank loans and public bonds. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 52, 1–31.

Hauptmann, C. (2017). Corporate Sustainability Performance and Bank Loan Pricing: It Pays to Be Good, but Only When Banks Are Too. Saïd Business School WP 2017–20.

Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. E. (1997). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Review of Economic Studies, 64, 605–654.

Herbohn, K., Gao, R., & Clarkson, P. (2019). Evidence on whether banks consider carbon risk in their lending Decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 155–175.

Hoechle, D., Schmid, M., Walter, I., & Yermack, D. (2012). How much of the diversification discount can be explained by poor corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 103, 41–60.

Hong, H., & Kacperczyk, M. (2009). The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 93, 15–36.

Irvine, P. J., & Pontiff, J. (2009). Idiosyncratic return volatility, cash flows, and product market competition. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 1149–1177.

Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American Economic Review, 76, 323–329.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Agency Costs and the Theory of the Firm. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

Jiraporn, P., Jiraporn, N., Boeprasert, A., & Chang, K. (2014). Does corporate social responsibility (CSR) improve credit ratings? Evidence from geographic identification. Financial Management, 43, 505–531.

Jones, T. M. (1995). Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Academy of Management Review, 20, 404–437.

Jung, J., Herbohn, K., & Clarkson, P. (2018). Carbon risk, Carbon risk awareness and the cost of debt financing. Journal of Business Ethics, 150, 1151–1171.

Kitson, A. (1996). Taking the pulse: Ethics and the British cooperative bank. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 1021–1031.

Kirschenmann. K., &Norden, L. (2012). The relationship between borrowerrisk and loan maturity in small business lending. Business Finance Accounting 39, 730–757

Klein, A. (2002). Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33, 375–400.

Lambert, R., Leuz, C., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2007). Accounting information, disclosure, and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 45, 385–420.

Levine, R. (2005). Finance and growth: Theory and evidence. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 865–934). North-Holland: Elsevier.

Levine, R., Lin, C., & Xie, W. (2018). Corporate resilience to banking crises: The roles of trust and trade credit. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 53, 1441–1477.

Meskin, M. (2019). Loans in brief: 18/04/2019. Global Capital.

Minton, B. A., & Schrand, C. (1999). The impact of cash flow volatility on discretionary investment and the costs of debt and equity financing. Journal of Financial Economics, 54, 423–460.

Murphy, K. J. (1985). Corporate performance and managerial remuneration: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 7, 11–42.

Neanidis, K. (2019). Volatile capital flows and economic growth: The role of banking supervision. Journal of Financial Stability, 40, 77–93.

Park, C.-Y., & Shin, K. (2020). Contagion through national and regional exposures to foreign banks during the global financial crisis. Journal of Financial Stability, 46, 100721.

Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 435–480.

Qian, J., & Strahan, P. E. (2007). How laws and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. Journal of Finance, 62, 2803–2834.

Rajgopal, S., & Shevlin, T. (2002). Empirical evidence on the relation between stock option compensation and risk taking. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33, 145–171.

Roberts, M. R., & Whited, T. (2013). Endogeneity in corporate finance. In G. M. Constantinides, M. Harris, & R. M. Stulz (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Finance (pp. 493–572). AMS: North Holland.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55.

Schneider, T. E. (2011). Is environmental performance a determinant of bond pricing? Evidence from the U.S. pulp and paper and chemical industries. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28, 1537–1561.

Scholtens, B., & Dam, L. (2007). Banking on the Equator. Are banks that adopted the Equator Principles different from non-adopters? World Development, 35, 1307–1328.

Scholtens, B. (2009). Corporate social responsibility in the international banking industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 159–175.

Scott, A. (2019, April), Kemira loan terms linked to sustainability, Chemical and Engineering News, American Chemical Society, 97, (17).

Sharfman, M. P., & Fernando, C. S. (2008). Environmental risk management and the cost of capital. Strategic Management Journal, 29, 569–592.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The Journal of Finance, 52, 737–783.

Tirole, J. (2001). Corporate governance. Econometrica, 69, 1–35.

Tucker, J. W. (2010). Selection bias and econometric remedies in accounting and finance research. Journal of Accounting Literature, 29, 31–57.

UNEP. (1992). Banking and the Environment -A Statement by Banks on the Environment and Sustainable Development. United Nations Environment Programme.

White, H. (1980). A Heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–838.

Whitehouse, L. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: Views from the frontline. Journal of Business Ethics, 63, 279–296.

Acknowledgements

Chih-Yung Lin wishes to acknowledge financial support under Grant MOST108-2636-H-009-001 from the Young Scholar Fellowship Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) in Taiwan. Any remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Definitions of variables

Appendix: Definitions of variables

Variable group | Definition | Data source |

|---|---|---|

A. Dependent variables | ||

Chemical emissions (CE) | The ratio of the total amount of toxic chemicals emitted to the total sales of a firm. Data include approximately 300 selected toxic chemicals from domestic manufacturing facilities owned by the firm or its subsidiaries and whose emissions are required to be disclosed under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act | TRI (EPA) and Compustat |

CE/Asset | The ratio of the total amount of toxic chemicals emitted to the total assets of a firm | TRI (EPA) and Compustat |

CE/NI | The ratio of the total amount of toxic chemicals emitted to the total net income of a firm | TRI (EPA) and Compustat |

B. Loan characteristics | ||

Ln(Spread) | Natural logarithm of the loan spread. Here, the loan spread is the all-in spread drawn from the DealScan database (the amount the borrower pays in terms of basis points over LIBOR or LIBOR equivalent for each dollar drawn down) | DealScan |

Ln(Maturity) | Natural logarithm of the loan maturity in months | DealScan |

Ln(Loan size) | Natural logarithm of the loan amount in US$ millions | DealScan |

Performance | Dummy variable that is equal to one if the loan facility uses performance pricing, and zero otherwise | DealScan |

Ln(Covenant) | Natural logarithm of the number of total covenants | DealScan |

Collateral | Dummy variable that is equal to one if a loan is secured, and zero otherwise | DealScan |

Ln(TCB) | Total cost of borrowing that is calculated as the natural logarithm of the total costs of a bank loan that include spread and other fees in the loan contracts | BSS (2016) |

C. Firm characteristics | ||

Ln(Assets) | Natural logarithm of the total assets in US$ millions | Compustat |

Leverage | Ratio of long-term debt plus debt in current liabilities to total assets | Compustat |

MB | Ratio of market value of net assets to book value of net assets | Compustat and CRSP |

Tangibility | Ratio of net property, plant, and equipment to total assets | Compustat |

Profitability | Ratio of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) to total assets | Compustat |

CF-volatility | Ratio of standard deviation of quarterly cash flows from operations over the four fiscal years prior to the loan initiation year, scaled by total debt | Compustat |

D. Macroeconomic factors | ||

Credit spread | Difference between the US AAA corporate bond yield and the BAA corporate bond yield | Datastream |

Term spread | Difference between the 10-year and 2-year US Treasury yields | Datastream |

E. Firm risk | ||

Z-score | Altman’s Z-score index. Z-score = 1.2 \(\times\)(working capital/total assets) + 1.4 \(\times\)(retained earningsl/total assets) + 3.3 \(\times\)(earnings before interest and taxl/total assets) + 0.6 \(\times\)(market value of equityl/total liabilities) + 1.0 \(\times\)(salesl/total assets) | Comp and CRSP |

EDF | Expected default frequency measure of the firm. It is the percentile ranking of a firm’s default risk based on its distance to default drawn from Bharath and Shumway (2008) | Comp and CRSP |

Idiovol | The standard deviation in the residuals obtained from a market model of daily returns that exceed the three-month T − bill by using the previous two-year data, where the market is represented by the value-weighted CRSP index | CRSP |

Beta | Firm’s equity beta from a market model of daily returns that exceed the three-month T-bill by using the previous two-year data, where the market is represented by the value-weighted CRSP index | CRSP |

F. Corporate governance | ||

Independent | The percentage of outside directors | RiskMetrics |

Busy | A dummy variable for whether a director is busy that equals one if a majority of directors hold three or more directorships | RiskMetrics |

Instown | Percentage share of ownership by institutional investors | 13F |

Boardsize | The number of board members | RiskMetrics |

Duality | A dummy variable for when the CEO also holds the position of chairman of the board | RiskMetrics |

CEOTC | The natural log of total compensation of the CEO. Total compensation (TDC1) includes salary, bonus, stock awards, option awards, long-term incentive plans, and other annual compensation such as perquisites and other personal benefits | ExecuComp |

Attend | A variable to measure attendance problems for the board of directors that equals the fraction of directors who attend less than 75% of board meetings | RiskMetrics |

Governance | A variable to measure corporate governance that is the first principal component from a PCA based on seven governance variables | Authors |

G. Bank social responsibility | ||

Bank_SR | The social responsibility of a bank. Bank_SR = CSR strength – CSR concern. CSR strength (concern) is the sum of the ratios of the number of CSR strengths (concerns) of firm i to the total number of strength indicators across the seven rating dimensions in the KLD dataset | KLD |

H. Social norm | ||

SK | The social capital measure of a firm that is the first principal component from a PCA based on Pvote, Respn, Nccs, and Assn (Hasan et al. 2017). In here, Pvote is the percentage of voters who voted in presidential elections, Respn is the response rate to the Census Bureau’s decennial census, Nccs is the sum of tax-exempt non-profit organizations per 10,000 people, and Assn is the sum of social organizations per 100,000 people | NRCRD |

.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, IJ., Hasan, I., Lin, CY. et al. Do Banks Value Borrowers' Environmental Record? Evidence from Financial Contracts. J Bus Ethics 174, 687–713 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04621-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04621-2