Abstract

Thomas Christiano argues that democracies acquire a right to rule by being the unique embodiment of publicly accessible rules. Justice requires the equal advancement of the interests of all (the equality requirement). However, due to the need for citizens to shape a common world despite disagreement and limitations of human cognition, publicity is a necessary constraint on the pursuit of justice (the publicity constraint). Given that democracy is necessary to secure public equality, democratic authority is thus justified, as democracy is the only political arrangement that satisfies both the publicity constraint and equality requirement. Christiano’s argument depends on a claim that individuals should be given the right to advance what they take to be their interests. This right is defended through two interlocking claims. First, according individuals this right advances three fundamental interests: i) correcting cognitive biases; ii) being at home in the world; and iii) equal moral standing. Second, the three fundamental interests imply that any collective decision-making procedure must be publicly accessible. Thus, any argument against the right to judge for oneself either violates the publicity requirement or the equality constraint. In this paper, I argue that Christiano’s argument faces a problem—under a two-stage plural voting system, an unequal distribution of voting rights can satisfy both the publicity requirement and the equality constraint. Thus, Christiano’s claim that public equality requires an equal distribution of the right to judge for oneself is mistaken.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is a common criticism against Christiano’s account of democracy. See for example Wall 2007. I take it that the argument for the equal right to judge for oneself that I explicate in the text is meant to provide a defense of Christiano’s account against critics like Wall.

As Croskerry et al. 2013 write, “a variety of cognitive and affective biases are known to compromise the decision-making process. They mostly appear to originate in the fast intuitive processes of Type 1 that dominate (or drive) decision making. Type 1 processes may work well most of the time but open the door for biases.”

Importantly, Christiano does not claim that we must assume equal competency in all matters. He holds that equality of competency with respect to judging what is in one’s own interest is compatible with inequality in terms of technical expertise, and that the latter can justify inequalities in terms of a cognitive division of labor where citizens set the ends and experts determine how best to achieve these ends. As such, it is unclear if his theory has the resources to deny that there is a meaningful distinction between the capacity to judge and debiasing competency.

Importantly, as many empirical studies suggest, the distinction between judgment competency and debiasing competency does not map neatly onto our traditional notion of expertise. See Hinds 1999.

The scheme here is adapted from Trevor Latimer’s procedural plural voting scheme in Latimer 2015.

I assume that technical information about debiasing techniques and what debiasing entails is made publicly accessible to lay audience. However, individuals ultimately make their own subjective assessment of what debiasing competency entails based on the available evidence.

The same holds for a case where some individuals exercise option 1 and all others exercise option 3, resulting in an unequal distribution of voting rights.

See Christiano 2009.

References

Christiano, T. (2001). Knowledge and power in the justification of democracy. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 79, 197.

Christiano, T. (2003). Philosophy and Democracy: An Anthology. (Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K.).

Christiano, T. (2004). The Authority of Democracy. Journal of Political Philosophy, 12, 266–290.

Christiano, T. (2008). The Constitution of Equality: democratic authority and its limits. (Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K.).

Christiano, T. (2009). Must democracy be reasonable? Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 39, 1–34.

Christiano, Thomas. 2015. 'Disagreement and the justification of democracy.' in, The Cambridge Companion to Liberalism.

Croskerry, Pat, Geeta Singhal, and Sílvia Mamede. 2013. 'Cognitive debiasing 1: Origins of bias and theory of debiasing', BMJ quality & safety, 22 Suppl 2: ii58-ii64.

Davis, Paul K., Jonathan Kulick, and Michael Egner. 2005. Implications of modern decision science for military decision-support systems (Rand, project air force: Santa Monica, CA).

Estlund, David M. 2008. Democratic authority: a philosophical framework (Princeton University Press: Princeton, N.J).

Evans, J. S. B. T., & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Dual-process theories of higher cognition: Advancing the debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 223–241.

Hinds, P. J. (1999). The curse of expertise: The effects of expertise and Debiasing methods on predictions of novice performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 5, 205–221.

Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York.

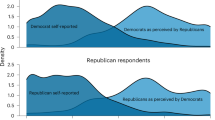

Kenyon, T. (2014). False polarization: Debiasing as applied social epistemology. Synthese, 191, 2529–2547.

Kunda, Ziva. 1999. Social cognition: making sense of people (MIT press: Cambridge, mass).

Latimer, Trevor. 2015 'Plural voting and political equality: A thought experiment in democratic theory', European Journal of Political Theory, 0: 1474885115591344.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Ammirati, R., & Landfield, K. (2009). Giving Debiasing away: Can psychological research on correcting cognitive errors promote human welfare? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 390–398.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The "false consensus effect": An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 279–301.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 755–769.

Tetlock, Philip E. 2005. Expert political judgment: how good is it? How can we know? (Princeton University Press: Princeton, N.J).

Wall, S. (2007). Democracy and equality. The Philosophical Quarterly, 57, 416–438.

Yokum, D. V. (2014). Debiasing the courtroom: Using behavioral insights to avoid and mitigate cognitive biases. In In, 347 pages. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Christiano’s argument for democratic authority finds its fullest expression in Christiano 2008. However, he develops and defends important aspects of this view in Christiano 2004; Christiano 2001; and Christiano 2015. In examining his views, I will refer to all of these works.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chow, J.K. Equality, Bias, and the Right to an Equal Say. Philosophia 48, 893–900 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-019-00135-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-019-00135-y