Abstract

There is widespread agreement about a combination of attributes that someone needs to possess if they are to be counted as a conservative. They need to lack definite political ideals, goals or ends, to prefer the political status quo to its alternatives, and to be risk averse. Why should these three highly distinct attributes, which are widely believed to be characteristic of adherents to a significant political position, cluster together? Here I draw on prospect theory to develop an explanation for the clustering of attributes that is characteristic of conservatives. I argue that a lack of political ideals is the underlying driver of conservatism. I will provide reason to believe that people who lack political ideals are disposed to prefer the political status quo to its alternatives; and reason to believe that people who prefer the political status quo to its alternatives are disposed to be risk averse, at least with respect to significantly many of the risks that arise in the social and political domain. I also consider and reject some other potential explanations for the clustering of attributes that is characteristic of conservatives and sketch some policy implications that follow from the explanation I develop.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to Brennan and Hamlin, conservatism ‘… is a disposition that grants the status quo a normative authority by virtue of its being the status quo’ (2004, p. 676). According to Beckstein, the truly conservative ‘… attach a value to the status quo because it is the status quo’ (2015, p. 18). O’Hara depicts conservatism as involving a recognition that ‘the current state of society is typically undervalued’ (2011, p. 88).

O’Hara offers what appears to be a deductive argument, from the premises that ‘the current state of society is typically undervalued and [because] the effects of social innovations cannot be fully known in advance’, to the conclusion that societies should be risk averse (2011, p. 88). The argument is not valid. It may perhaps be intended as an inference to the best explanation which been not been fully fleshed out.

Mueller concurs. According to him, ‘Libertarianism is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a form of conservatism’. He depicts libertarianism as ‘part of a broad conservative coalition, especially in the United States’, rather than a form of conservatism (2005, p. 364).

The difference between American and non-American uses of the term ‘conservative’ has given rise to some potentially confusing commentary. Some commentators, such as Handlin (1963, p. 446) have denied that there are any true conservatives in America. Others, such as Kirk (1953), have argued that America ought to change in various ways, to allow a genuinely conservative political movement to develop.

E. G. Huntington (1957, p. 455).

Beckstein argues similarly (2015, p. 12).

E. G. Viereck (2009, pp. 153–4).

In a similar vein, Kekes suggests that conservatives should regard a status quo that involves slavery as unacceptable (1998, p. 40)

According to O’Hara, conservatives should concede that they do not know that any given social reform will be unsuccessful, and should welcome social reforms that have been implemented, when it becomes clear that the benefits of these have outweighed costs (2011, pp. 56–7).

A suggestion I will not pursue here is one due to Turner (2010) and Briggle (2014). Both authors suggest that conservative attitudes to risk are embodied in the ‘precautionary principle’. There is no one canonical formulation of the precautionary principle. Instead there are several different formulations, all of which raise significant conceptual difficulties (Clarke 2009). The core idea behind the principle is something like ‘when in doubt don’t’, or ‘better safe than sorry’ (Sandin 2007, p. 100). The precautionary principle does not seem to add much, if anything, to the idea of risk aversion, so not much will be lost here by ignoring it.

A complicating factor here is that a significant minority of the people who identify as conservatives and live in American Red States are libertarians, and so not conservative in the sense that is relevant to my argument. 11% of Americans describe themselves as libertarian (and understand what the term means) (Kiley 2014). This complication does not change the fact that the pattern of distribution of wealth in America favour liberals and disadvantages conservatives.

See http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2014/jul/29/facebook-posts/are-97-nations-100-poorest-counties-red-states/ (accessed 16 September 2016).

Jost et al. (2007) go close to suggesting that there is evidence that conservatives are risk averse. They argue that there is evidence that conservatives have a heightened need to manage uncertainty and threat. The presence of this alleged need might be thought to imply that conservatives are risk-averse. However, a need to manage uncertainty and threat could sometimes lead to risk-seeking rather than risk-averse behaviour. This might well be the case if potential threats can be headed off by accepting rather than avoiding risks, or if imminent threats can be more effectively managed by taking risks than by avoiding them.

There are also various other less significant contributors to status quo bias. For a recent summary, see Eidelman and Crandall (2012).

There may well be costs involved in switching between options. If so, then these can provide me with a reason to prefer to avoid switching. Thanks to an anonymous referee for this point.

As of 6 May 2017, Kahneman and Tversky (1979), the paper in which the core ideas of prospect theory were first set out, had been cited 45,703 times (Google Scholar). According to Levy ‘the behavioural alternative to expected utility that has received by far the most attention in political science is prospect theory’ (2003, p. 215). Prospect theory has been hugely successful but it has some limitations. It appears to be unable to account for the apparent roles that feelings of disappointment and regret play in shaping our responses to risk (Kahneman 2011, pp. 286–8).

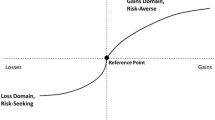

The three central claims presented here are shortened versions of Kahneman’s three central principles of prospect theory (2011, p. 282).

What exactly is a reference point? According to Kahneman (2011) it is ‘the earlier state relative to which gains and losses are evaluated’ (2011, p. 281). Van Osch et al., describe a reference point as a ‘point of view’ (2006, p. 338). Köszegi and Rabin offer a definition of reference points tailored to business: ‘a person’s reference point is her probabilistic beliefs about the relevant consumption outcome held between the time she first focused on the decision determining the outcome and shortly before consumption occurs’ (2006, p. 1141).

See also Figure 10, Kahneman (2011, p. 283).

For further discussion of prospect theory’s ability to account for evidence of the endowment effect, see Kahneman (2011, pp. 292–7).

Also social norms, social comparisons and recent losses (Levy 2003, p. 218).

Relatedly, they are motivated to work harder to meet goals than to exceed goals (Heath et al. 1999, pp. 83–6).

65 research subjects were asked to choose under the ‘do your best’ condition’ and 66 subjects were asked to choose under the ‘save $250,000′ condition (Heath et al. 1999, p. 94).

Pope and Schweitzer suggest that par may not always be the only reference point for professional golfers. On an easy par-five hole, expert golfers may come to treat a score of four as their reference point (2011, p. 149). Also, late in a tournament, the scores of competitors may become reference points (2011, p. 130).

Interestingly, some professional golfers, such as Tiger Woods, are aware that their behaviour when putting for birdie is different from their behaviour when putting for par (Pope and Schweitzer 2011, pp. 144–5).

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswick, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian personality. New York: Harper.

Beckstein, M. (2015). What does it take to be a true conservative? Global Discourse, 5, 4–21.

Brennan, G., & Hamlin, A. (2004). Analytic conservatism. British Journal of Political Science, 34, 675–691.

Briggle, A. (2014). Bioconservatism as customised science. In S. Fuller, M. Stenmark, & U. Zackariasson (Eds.), The customization of science: the impact of political and religious worldview on contemporary science (pp. 176–192). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Buchanan, A. (2011). Beyond humanity? The ethics of biomedical enhancement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29(6), 807–840.

Choma, B. L., Hanoch, Y., Hodson, G., & Gummerum, M. (2014). Risk propensity among liberals and conservatives: The effect of risk perception, expected benefits and risk domain. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5, 713–721.

Clarke, S. (2009). ‘New technologies, common sense and the paradoxical precautionary principle’. In P. Sollie and M. Duwell (Eds.), Evaluating new technologies: methodological problems for the ethical assessment of technological developments (pp. 159–173). Dordrecht: Springer.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550.

Eidelman, S., & Crandall, C. S. (2012). Bias in favour of the status quo. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(3), 270–281.

Handlin, O. (1963). The American people. Hamondsworth: Penguin.

Heath, C., Larick, R., & Wu, G. (1999). Goal as reference points. Cognitive Psychology, 38, 79–109.

Huntington, S. (1957). Conservatism as an ideology. American Political Science Review, 51, 454–473.

Jost, J. T., Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., Gosling, S. D., Palfai, T. P., & Ostafin, B. (2007). Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 989–1007.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: the endowment effect, loss aversion and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, XLVII, 263–291.

Kekes, J. (1998). A case for conservatism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kiley, Jocelyn (2014). In search of libertarians. Pew Research Center. Avaiable at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/08/25/in-search-of-libertarians/. Accessed 19 October 2016.

Kirk, Russell. (1953) [2008]. The conservative mind. New York: BN Publishing.

Köszegi, B., & Rabin, M. (2006). A model of reference-dependent preferences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121, 1133–1165.

Levy, J. S. (2003). Applications of Prospect theory to political science. Synthese, 135, 215–241.

Martin, J. L. (2001). The authoritarian personality, 50 years later: what lessons are there for personality psychology? Political Psychology, 22, 1–26.

Mehrabian, A. (1996). Relations among political attitudes, personality and psychopathology assessed with new measures of libertarianism and conservatism. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18, 469–491.

Mueller, J.-W. (2006). Comprehending conservatism: A new framework for analysis. Journal of Political Ideologies, 11(3), 359–365.

O’Hara, K. (2011). Conservatism. London: Reaktion.

Oakeshott, Michael. (1962). ‘On being conservative’, in Rationalism in politics and other essays, New York: Basic Books, pp. 168–196.

Orwell, G. (1949). Nineteen eighty-four. London: Secker and Warburg.

Owens, Jared. (2014). ‘Advocates of sharia law should leave, or lose voting and welfare rights: Jacqui Lambie’, The Australian, 15 September. Available at: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/advocates-of-sharia-law-should-leave-or-lose-voting-and-welfare-rights-jacqui-lambie/story-fn59niix-1227059026256. Accessed 16 September 2016.

Pope, D. G., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2011). Is Tiger Woods loss averse? Persistent bias in the face of experience, competition and high stakes. American Economic Review, 101, 129–157.

Ray, J. J. (1988). Cognitive style as a predictor of authoritarianism, conservatism and racism, a fantasy in many movements. Political Psychology, 9, 303–308.

Sandin, P. (2007). Common-sense precaution and varieties of the precautionary principle. In T. Lewens (Ed.), Risk: philosophical perspectives (pp. 99–112). London: Routledge.

Scruton, R. (2002). The meaning of conservatism (3rd ed.). South Bend: Saint Augustine’s Press.

Scruton, R. (2014). How to be a conservative. London: Bloomsbury Continuum.

Sears, D. O., & Funk, C. L. (1991). The role of self-interest in social and political attitudes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 1–85.

Tetlock, P. E. (1994). Political psychology or politicised psychology: Is the road to scientific hell paved with good moral intentions? Political Psychology, 15, 509–529.

Turner, S. P. (2010). The conservative disposition and the precautionary principle. In C. Abel Exeter (Ed.), The meaning of Michael Oakeshott’s conservatism (pp. 204–217). Imprint Academic.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211, 453–458.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in Prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

Van Osch, S. M. C., van den Hout, W. B., & Stiggelbout, A. M. (2006). Exploring the reference point in Prospect theory: gambles for length of life. Medical Decision Making, 26, 338–346.

Viereck, P. (2009). Conservatism revisited: the revolt against ideology. New Brunswick: Transaction (3rd Printing).

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Wylie Breckenridge, Dan Cohen, Dan Halliday, Matthew Kopec, Morgan Luck, Kate MacDonald, Terry MacDonald, Emma Rush and Anne Schwenkenbecher, as well audience at the University of Melbourne and the Australian National University, and an anonymous referee for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Research leading to its developments was supported by Australian Research Council Grant DP130103658.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clarke, S. A Prospect Theory Approach to Understanding Conservatism. Philosophia 45, 551–568 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-017-9845-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-017-9845-9