Abstract

There is good reason to think that, in every case of perceptual consciousness, there is something of which we are conscious; but there is also good reason to think that, in some cases of perceptual consciousness—for instance, hallucinations—there is nothing of which we are conscious. This paper resolves this inconsistency—which we call the presentation problem—by (a) arguing that ‘conscious of’ and related expressions function as intensional transitive verbs and (b) defending a particular semantic approach to such verbs, on which they have readings that lack direct objects or themes. The paper further argues that this approach serves not only as a linguistic proposal about the semantics of ‘conscious of’, but also as a proposal about the metaphysics of conscious states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper sets out a new solution to a classical problem. The problem, which we will call here the presentation problem, arises from an inconsistency in the way we think about perceptual consciousness.Footnote 1 On the one hand, we are inclined to think that, in every case of perceptual consciousness, there is something of which you are conscious. On the other hand, we are inclined to think that, in at least some cases—hallucinations, for instance—there is nothing of which you are conscious. Since these inclinations are inconsistent, there appears to be a contradiction at the heart of our understanding of perceptual consciousness.

The solution we offer starts from the idea that ‘conscious of’ and related constructions such as ‘aware of’ and ‘attend to’ function semantically as intensional transitive verbs (ITVs), which is to say that they are in the same semantic category as expressions such as ‘seeks,’ ‘hunts,’ ‘wants’ and so on.Footnote 2 ITVs have been famous in philosophy at least since Quine drew a distinction between their notional and relational readings in ‘Quantifiers and Propositional Attitudes’ (Quine, 1956). But recent literature in linguistics and philosophy of language has provided considerable further insight into them; we have particularly in mind the version of event semantics for such verbs developed by Graeme Forbes, and a key consequence of this view, namely, that ITVs on their notional readings have no direct objects or themes.Footnote 3

With this as background, our initial proposal is, first, that an event semantics of this sort is true of ‘conscious of’ and similar expressions and, second, that if this is the case we may solve the presentation problem. The novelty of this proposal is that, to the extent that philosophy of mind and perception has focused on ‘conscious of’ or ‘aware of’ at all, the assumption has been that their object positions are fully extensional.Footnote 4 But no view of this sort, we think, has a plausible answer to the presentation problem.

While developments in the philosophy of language and linguistics provide the materials for our solution, our ultimate proposal is not about language. It is that there is a distinction between thematic and non-thematic states (as we will call them) of perceptual consciousness, and that hallucinations, unlike veridical perceptual states, are non-thematic. Attending to this distinction solves the presentation problem, and forms the basis of a new, more general theory of the metaphysics of conscious perceptual states.

Section 2 describes the problem in more detail, while Sect. 3 and 4 review the semantic ideas that provide the materials for our solution. Section 5 then sets out that solution and Sect. 6 shows how it serves as a novel theory of perceptual consciousness, rather than merely a semantic proposal. Section 7 briefly explains why problems with existing views motivate adopting our own.

2 The presentation problem

The presentation problem arises from an inconsistency in what we are inclined to believe about perceptual consciousness. We may express these inclinations as the following contradictory principles:

- P1:

-

In every state of perceptual consciousness, there is something of which you, the subject of that state, are conscious.Footnote 5

- P2:

-

In some states of perceptual consciousness, there is nothing of which you, the subject of that state, are conscious.Footnote 6

P1 articulates a widely-held intuition concerning perceptual consciousness: that in any such state, veridical or otherwise, there is something presented to you—and you are conscious of what is presented to you. P2 is plausible because there appear to be states of perceptual consciousness in which there is nothing at all of which you are conscious—namely, hallucinations, which for our purposes are states that are phenomenally equivalent to states in which you veridically perceive an object, but in which that object does not exist.Footnote 7 In such cases, there are no good candidates for being the object of which you are conscious.

Clearly something has gone wrong, but before asking what it is, let us look at the arguments for P1 and P2 in more depth.

2.1 The case for P1

There are several potential arguments for P1; here we will concentrate on three, each of which may be extracted from a famous discussion in the philosophy of perception.Footnote 8

Our text for the first argument, which we will call Price’s argument, is this passage from H.H.Price:

When I see a tomato there is much that I can doubt. I can doubt whether it is a tomato that I am seeing, and not a cleverly painted piece of wax. I can doubt whether there is a material thing there at all ...One thing however I cannot doubt: that there exists a red patch of a round and somewhat bulgy shape, standing out from a background of other colour-patches, and having a certain visual depth, and that this whole field of colour is presented to my consciousness ...that something is red and round then and there I cannot doubt ...Price (1933, p. 3)

Price’s premise is that, when you are conscious of a tomato, even if you are hallucinating, it is impossible to doubt that there is something red and round which is presented to your consciousness. This seems tantamount to saying that, in such cases, it is impossible to doubt that there is something red and round of which you are conscious.

How should we understand the notion of possibility at issue here? Price surely means that in the situation he describes, it is epistemically—rather than, for instance, psychologically—impossible to doubt that there is something red and round of which you are conscious. Given this understanding, the path to P1 is wide open. For from ‘it is (epistemically) impossible to doubt that there is something red and round of which you are conscious’, you may infer ‘there is something red and round of which you are conscious’, and from this, in turn, you may infer ‘there is something of which you are conscious’. Since such reasoning holds for any state of perceptual consciousness, we arrive at P1: in every such state, there is something of which you are conscious.

Our text for the second argument for P1, which we will call Broad’s argument, is this passage from C.D.Broad:

When I look at a penny from the side I am certainly aware of something; and it is certainly plausible to hold that this something is elliptical ...If, in fact, nothing elliptical is before my mind, it is very hard to understand why the penny should seem elliptical rather than of any other shape. Broad (1927, p. 240)

Broad is concerned here with illusion rather than hallucination, but the passage naturally applies to both. His basic suggestion, to revert to Price’s sort of example, is that an hallucination of a tomato is very different from an hallucination of a banana, even though no relevant tomato or banana exists. He then suggests that the best explanation, and perhaps the only explanation, of this is that, even in hallucination, there is something of which you are conscious. If, in an hallucination, you are not conscious of anything, such an explanation would be unavailable. Hence, as before, we arrive at P1: in every state of perceptual consciousness, there is something of which you are conscious.

Our text for the third argument, which we call the Smith’s argument, is this passage from A.D.Smith:

To say simply that our subject is not aware of anything is surely to underdescribe this situation dramatically ...we need to be able to account for the perceptual attention that may well be present in hallucination. A hallucinating subject may, for example, be mentally focusing on one element in a hallucinated scene, and then another, describing in minute detail what he is aware of ... The sensory features of the situation need to be accounted for. How can this be done if such subjects are denied an object of awareness? Smith (2002, pp. 224–225), as quoted in Pautz 2007, 504)

Smith’s point is that, in cases of hallucination, you are not simply conscious of something, you can also attend to what you are conscious of. There is an identity, in other words, between what you are conscious of and what you attend to.Footnote 9 To explain this fact about intentional identity, Smith says, we must suppose that there is something even in hallucination of which you are conscious, something to which you can also attend. Reasoning as before, we arrive at P1: in every state of perceptual consciousness, there is something of which you are conscious.

2.2 The case for P2

Turning now to P2, the argument for this proceeds from two premises. The first is that, if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is either a particular or a property. The second is that, if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is neither a particular nor a property. These two premises jointly imply that there is nothing of which you are conscious in an hallucination. But, given that hallucinations are themselves states of perceptual consciousness, we obtain P2: in some states of perceptual consciousness, there is nothing of which you are conscious.

Why believe that, if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is either a particular or a property? Notice to begin with that, if there is something of which you are conscious, it is either a particular or not—that is a necessary truth. And if something is not a particular, it must be something general, something that can be instantiated by other things, particular or themselves general. Of course there are many kinds of things that can be instantiated: Aristotelian universals, Platonic universals, generalized quantifiers, and perhaps others. For our purposes, it is sufficient to ignore these distinctions, and call things that can be instantiated properties. Thus, from a necessary truth together with our definition of a property, we arrive at the first premise of the argument for P2: if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is either a particular or a property.

Why believe that, if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is neither a particular nor a property? The crucial consideration here is that, in non-veridical hallucination, there is simply no candidate to be the relevant particular or property.

To see this, notice first that in hallucinations as we are understanding them, there is no relevant existing physical particular, such as a tomato, of which you are conscious. By itself this does not rule out a particular that either does not exist or is not physical. In fact, Price, Broad and Smith are all alert to this possibility. As a result, Price and Broad become sense-datum theorists; they claim that in hallucination we are aware of mental particulars, i.e., sense-data. Smith becomes a Meinongian, for whom the relevant particulars subsist rather than exist. We won’t assess these ideas here, but it is fair to say that the contemporary consensus in philosophy of perception and consciousness is that both of these views face such serious problems that they should be set aside, and that will be our procedure.

But what about the other idea present in the reasoning above, namely, that in hallucination we are conscious, not of a particular but of a property? If we adopt this suggestion, we may say that, in the case in which we are visually hallucinating a tomato, what we are conscious of are the properties of redness and roundness, or perhaps some complex thereof.

Actually, this suggestion has many adherents in the contemporary literature,Footnote 10 but it confronts an apparently insuperable difficulty. The problem is not the absence of relevant existing properties in hallucinatory cases; given how liberal our definition of a property is, there is no shortage of such things. It is rather that (a) the relevant properties are uninstantiated, and (b) uninstantiated properties do not have the right features to be the things of which we are conscious.

To illustrate, take again the case in which we hallucinate a tomato, and so are conscious of a red, round thing in a particular location and of a particular size. On the view we are considering, in such a case we are conscious of an uninstantiated property, e.g., the property of being red or of being round, or perhaps the conjunctive property of being red and round. But, to adopt Smith’s phrase from the passage quoted above, this is to mis-describe the situation dramatically. Uninstantiated properties have no particular location or size, for example, but the thing of which we are conscious has both.Footnote 11.

The upshot of these considerations seems to be this: if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it cannot be a property but must be a particular. But as we saw before, there is no candidate particular it could be. Hence, we arrive at the second premise of the argument sketched above, that if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is neither a particular nor a property. Putting this together with the first premise yields P2: in some states of perceptual consciousness, there is nothing of which you are conscious.

3 Semantics for intensional transitives

So this is the presentation problem: there are good arguments for P1 and P2, and yet these principles are contradictory. In Sect. 5 we’ll turn to our solution, but first we need to describe the semantic ideas on which our approach relies, and apply them to ‘conscious of’.

3.1 Notional v. relational

There are three key features that sentences involving ITVs have on their notional readings and lack on their relational readings.Footnote 12

First, sentences involving ITVs on the notional reading can be true even when the noun phrases in their direct-object positions do not denote existent objects. On the notional reading, ‘Mary seeks Atlantis’ may be true, even though Atlantis does not exist, and never has. By contrast, if ‘Mary seeks Atlantis’ is true on its relational reading, then Atlantis exists.

Second, sentences involving ITVs, on the notional reading, need not relate the subject to a particular object. On the notional reading, ‘I seek a sloop’ may be true, even though I don’t seek a particular sloop—I may simply seek relief from slooplessness, to borrow Quine’s famous example. By contrast, if ‘I seek a sloop’ is true on the relational reading, there must be a particular sloop that I seek.

Finally, on their notional readings, sentences involving ITVs resist substitution of coextensive noun phrases in their object-positions. On this reading, ‘Mary seeks the best café in town’ may be true while ‘Mary seeks the best lunch spot’ is not—even if the best café is the best lunch spot. By contrast, on the relational reading, if ‘Mary seeks the best lunch spot’ is true, and the best café is the best lunch spot, then ‘Mary seeks the best café’ must also be true.

3.2 The notional as non-thematic

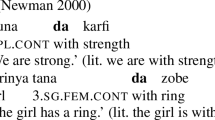

What is the semantic analysis of sentences with these features? Forbes’s (2006) presents his theory in a neo-Davidsonian event-based framework that employs several distinctive pieces of semantic machinery.

First, in this framework, verbs denote sets of events, and each sentence involves existential quantification over events. Thus, each sentence to which the theory applies says, at the very least, that there is an event of the kind denoted by the verb.Footnote 13

Second, each of a verb’s argument-places is associated with a distinctive thematic role. Thematic roles serve to specify the role that a particular object plays in an event. Some common thematic roles are: agent, theme, instrument, subject, cause, and location, among many others. Thus, on an event semantics, ‘John hit Bill’ has the following logical form:

-

(1)

There is an event e [hitting(e) & Agent(e,John) & Theme(e,Bill) & past(e)]

So, on this proposal, ‘John hit Bill’ is interpreted as meaning that there is a past event of hitting, of which John is the agent and of which Bill is the theme. The thematic roles Agent and Theme here correspond to ordinary subject and direct-object argument places: the agent of the event is the subject of the ascription, namely John, while the theme of the event is the direct object of the ascription, namely Bill. To a first approximation, we can identify the theme of a certain kind of event V by asking: “what gets V’d?” In our example above, Bill is the theme of the event of hitting because he gets hit.

Within this framework, Forbes’s proposal is that, while sentences involving ITVs on the relational reading have a theme, the same sentences on the notional reading do not: notional readings denote events that have no direct objects. Instead of a theme, notional readings have a novel thematic role that Forbes calls Char (short for “characterization” or “is characterized by”). Char is a relation between an event and a property.Footnote 14 However, for an event to be characterized by a property is not for the property to be the direct object of the event. Rather, an event is characterized by a property just in case it has certain success-conditions determined, at least in part, by that property.

To illustrate, consider this classic example:

-

(2)

Ponce seeks the fountain of youth.

For Forbes, on its relational reading, (2) has the logical form given in (3):

-

(3)

There is an event e [search(e) & Agent(e,Ponce) & Theme(e,the fountain of youth)]

On its notional reading, by contrast, (2) has the logical form given in (4):

-

(4)

There is an event e [search(e) & Agent(e,Ponce) & Char(e,the property of being the fountain of youth)]

(4) does not say that the property of being the fountain of youth is the theme of the event; the property is not what gets sought. Rather, the property characterizes Ponce’s search, which is to say that it specifies the search’s success conditions. How does it do so? Since searches are successful only if you find what you seek, in the case of ‘search’, Char can be spelled out with the extensional verb ‘find’. We may capture this as follows, where ’P’ is a schematic letter for a propertyFootnote 15:

-

(5)

Given a search e: Char(e,P) iff necessarily, every event e′ that makes esuccessful has a subevent in which the agent finds an x such that Px.

Thus, on the notional reading of (2), the nominal ‘the fountain of youth’ contributes a property to logical form that plays a distinctive role in the sentence’s argument-structure, and so a distinctive role in the event of searching that the sentence describes. But the role is not that of theme. Instead, when we say that Ponce is searching for the fountain of youth, we mean that a certain property characterizes his search. This property is not what Ponce hopes to find, rather he hopes to find something that has this property.

3.3 The notional reading and quantification

A final point that will be important as we proceed is that on the notional reading, quantificational NPs in the object position of an ITV do not function as first-order quantifiers over particulars. For example, if ‘Mary seeks three dogs’ is true, it does not follow that three dogs are such that Mary seeks them.

But we should not infer from this that generalization into the object position of an ITV on its notional reading is never valid. On the contrary, if ‘Mary seeks a fountain pen’ is true, then ‘Mary seeks something’ is also true. But ‘something’, as just used, is what Moltmann (1997), Moltmann (2003), Moltmann (2004), Moltmann (2008) calls a special quantifier. Syntactically, special quantifiers replace entire quantified noun phrases in intensional positions, and so do not commit us to the existence of particulars. But more importantly for our purposes, they also do not commit us to the existence of themes, particular or otherwise. From the fact that Mary seeks something, namely, a fountain pen, it does not follow that there is any object—particular or general—that serves as the theme of Mary’s search.

While a full theory of special quantifiers goes beyond the scope of this paper, we will adopt the following view. To say that Mary seeks something, on the notional reading, is to say that there is some property that characterizes her event of searching. Further, to say that she seeks something red and round, on the notional reading, is to say that her search is successful only if she finds a red, round thing. Thus, on our view, special quantifiers range over properties that characterize events, rather than over themes.Footnote 16

4 Applying the semantics

So far we have been speaking of ITVs in general. The hypothesis to be considered now is that ‘conscious of’, like ‘seeks’, functions semantically as an ITV, and in consequence, the semantics just considered applies to it.

4.1 ‘Conscious of’ as an ITV

Why think ‘conscious of’ exhibits the features characteristic of the notional reading of ITVs? One consideration is that (a) ’perceives’ is an ITV that empirically exhibits all three of these features, and so can be used to describe cases in which a subject hallucinates, and (b) ‘conscious of’, and similar expressions like ‘aware of’, pattern with ‘perceives’.Footnote 17 If ’perceives’ is an ITV, then sentences such as (6) can be true when Joan is hallucinating a unicorn:

-

(6)

Joan perceives a unicorn.

But if (6) is true in such a case, then it is surely also true that Joan is both aware of and conscious of a unicorn, which in turn entails that ‘aware of’ and ‘conscious of’ have notional readings. Supposing otherwise would lead to the strange view that Joan can consciously perceive something without being conscious of or aware of that thing—indeed, without being conscious of or aware of anything—and that is intuitively false.

There is also independent empirical reason to think that ‘conscious of’ has a notional reading. We designed and conducted a study that tested five phenomenal verbs (as we call them)—‘be conscious of’, ‘be aware of’, ‘pay attention to’, ‘focus on’, and ‘concentrate on’—for the first feature of ITVs: a lack of existential commitment in object position. The results of the study showed (a) that all of these phenomenal verbs exhibit this feature to the same degree as ‘admire’—which clearly has this feature—and (b) that these verbs contrast starkly with extensional verbs that do have such commitments, such as ‘kick’ and ‘hug’.Footnote 18 One might here point out that a lack of existential commitment in object position is not sufficient to establish the presence of a notional reading. But given our first argument showing that ‘conscious of’ patterns with ‘perceives’, which exhibits all three features, it is plausible that ‘conscious of’ does as well, and so has a notional reading.

Finally, a range of coordination data provide evidence that ‘conscious of’ exhibits the three features of ITVs. Consider the following three arguments. (i) If you perceive a unicorn, it may also be true that you are conscious of what you perceive. But since what you perceive is a unicorn, it follows that you are conscious of a unicorn. (ii) If you perceive a banana but no particular banana, it may also be true that you are conscious of what you perceive. But since what you perceive is a banana but no particular one, it follows that in such a case you can be conscious of a banana. (iii) Suppose you perceive Clark Kent and are conscious of what you perceive; it follows as before that you are conscious of Clark Kent. But it may not be true that you perceive, or are conscious of, Superman, even though Clark Kent is Superman.

These considerations make it plausible that there is a legitimate strand of English usage on which ‘conscious of’ and ‘aware of’ have notional readings. But we don’t want to insist that this is the only legitimate strand. There may well be communities—perhaps even within philosophy of mind and perception—in whose dialects these verbs are fully extensional. But what will be important for us in addressing the presentation problem is simply the availability of the notional reading, not its ubiquity.Footnote 19

4.2 Non-thematic semantics for ‘conscious of’

Even if ‘conscious of’ is an ITV, however, one may still wonder whether the event semantics reviewed earlier applies to it. For one thing, ‘conscious of’ reports a state rather than an event; for another, ‘seeks’ is explained in terms of the extensional ‘finds’—but what are the analogues of success and finding for the case of ‘conscious of’?

These points are important but not insurmountable. First, it is standard practice to generalize event-semantic frameworks so that verbs denote sets of eventualities, and then allow for quantification over this broader category. Following Parsons (1990), we can treat the category of eventualities as including events, processes, and states.

Second, just as searches can be successful or unsuccessful, states of perceptual consciousness can be correct or incorrect.Footnote 20 Thus, we can specify correctness conditions for the notional reading of ‘conscious of’ with a fully extensional verb, just as we did for the notional reading of ‘seeks’. Which fully extensional verb should we use in this case? Since ‘conscious of’ is an ITV, and has a relational reading in addition to a notional one, we can state the correctness conditions for the notional reading using the relational reading of the very same verb.

With these modifications in place, consider this example:

-

(7)

Henry is conscious of a tomato.

On its relational reading, (7) has the logical form given in (8):

-

(8)

There is a tomato x and a state s such that [consciousness(s) & Subject(s,Henry)& Theme(s,x)]Footnote 21

On its notional reading, by contrast, (7) has the logical form given in (9):

-

(9)

There is a state s such that [consciousness(s) & Subject(s,Henry) & Char(s,the property of being a tomato)]

As before, (9) does not say that Henry is conscious of the property of being a tomato; the property is not what he is conscious of. Rather, the property characterizes his state, which is to say that it specifies the state’s correctness conditions. In this case, Char may be spelled out as follows, where again, ’P’ is a schematic letter for a property:

-

(10)

Given a state of consciousness s, Char(s,P) iff necessarily, every state s′ in which s is correct is one in which the subject is relationally conscious of an x such that Px.Footnote 22

Once again, therefore, on the notional reading of (8), the direct-object nominal ‘a tomato’ contributes a property to logical form that plays a distinctive role in the sentence’s argument-structure.Footnote 23 But again the role is not that of theme. Instead, when we say that Henry is conscious of a tomato, we mean that this property specifies the correctness conditions of the state of which he is the subject: he is in a state that is correct only if he is conscious in the relational sense of something that is a tomato—i.e. only if he is in a conscious state whose theme is a tomato.

5 The solution

We saw before that the presentation problem consists in two contradictory principles, each of which we have reason to believe:

- P1:

-

In every state of perceptual consciousness, there is something of which you are conscious.

- P2:

-

In some states of perceptual consciousness, there is nothing of which you are conscious.

In light of the material we have just presented, however, it becomes possible to distinguish two readings of these principles.

Consider P1 first; on the relational reading, P1 is equivalent to:

- P1-R:

-

In every state of perceptual consciousness, there is some x such that the theme of your conscious state is x.

On the notional reading, by contrast, P1 is equivalent to:

- P1-N:

-

In every state of perceptual consciousness, there is some property F such that your conscious state is characterized by F.

The difference between P1-R and P1-N is that only the first implies that every state of perceptual consciousness consists in a relation to a direct object.

Next consider P2; on its relational reading, P2 is equivalent to:

- P2-R:

-

In some states of perceptual consciousness, there is no x such that the theme of your conscious state is x.

On the notional reading, by contrast, P2 is equivalent to:

- P2-N:

-

In some states of perceptual consciousness, there is no F such that your conscious state is characterized by F.

The difference between P2-R and P2-N is that only the second implies that some conscious states are not characterized by any property.

Our solution to the presentation problem may now be stated simply. The case for P1 that we set out earlier does indeed support P1-N, but it provides no support for P1-R. Likewise, the case for P2 does indeed support P2-R, but provides no support for P2-N. Moreover, given that P1-N and P2-N are contradictory, support for P1-N counts against P2-N. And, given that P1-R and P2-R are contradictory, support for P2-R counts against P1-R. Overall, therefore, we are in a position to reject P1-R and P2-N, and to accept P1-N and P2-R. But since P1-N and P2-R are not contradictory, the problem is solved.

Let us look in more detail at this solution.

5.1 The case for P1 revisited

The first argument for P1 was Price’s argument. In setting this out above, we said that its first premise was equivalent to the claim that it is impossible to doubt that there is a red and round thing of which you are conscious. If ‘conscious of’ is an ITV, however, there are two ways to interpret this premise. On the relational reading, which we adopted uncritically before, it means that it is impossible to doubt that there is a red and round thing that serves as the theme of your conscious state. But on the notional reading, it means that it is impossible to doubt that you are conscious of something red and round—i.e., it is impossible to doubt that your conscious state is characterized by the properties of being red and round. Once these two readings are distinguished, the argument is unpersuasive when construed as aiming at P1-R.

Suppose first the notional reading of the premise is in play. Then we may agree with Price that it is impossible to doubt, in the relevant circumstances, that you are conscious of something red and round. But from this, what follows is P1-N, not P1-R: the argument thus only supports the claim that every state of perceptual consciousness is characterized by a property.

Suppose now the relational reading is in play. Then the argument would, if sound, yield P1-R, but its main premise is now highly questionable. Is it really impossible to doubt, in the relevant circumstances, that there is a red and round thing that is the theme of your state? If so, all alternative hypotheses would have to be ruled out by whatever introspective grounds are available to you in this situation. But that is not so, since there is clearly one alternative hypothesis that has not been ruled out, namely, that you are conscious in the notional sense of a red and round thing; that is, your state of consciousness is characterized by these properties, but has no theme at all. On the relational reading, therefore, the first premise of the argument is false, and so the argument does not support P1-R.

Turning to Broad’s argument for P1, its first premise is that the state of hallucinating a tomato is different than a state of hallucinating a banana. Its second premise is that the best, and perhaps only explanation of this is to assume that in an hallucination there is something of which one is conscious in the relational sense. But in the light of what we have said, this second premise is implausible. A different and better way to explain the first premise is to say that in hallucinating a banana one is conscious in the notional sense of a banana, while in hallucinating a tomato one is conscious in the notional sense of a tomato. These are clearly different given the semantics we are operating with, since the first state is characterized by one property, while the second is characterized by another. Given the ease with which the idea of characterization explains the differences between these states, Broad’s argument is best construed as an argument for P1-N, rather than for P1-R.

Finally, consider Smith’s argument. The first premise of this argument is that, when we hallucinate a tomato we are not only conscious of a red and round thing, but we can also attend to the thing we are conscious of. The second premise is that the best, and perhaps only explanation of this is to assume that in hallucination there is some object that serves as the theme of one’s state. Once again, however, what we have said renders this second premise implausible. A different and better explanation of the first premise emerges if we suppose that not only is ‘conscious of’ an ITV, but that ‘attend to’ is one as well.

The idea that ‘attend to’ is an ITV is supported by the kinds of arguments that make the analogous claim plausible in the case of ‘conscious of’. First, given that ‘perceives’ and ‘conscious of’ both have notional readings, it is plausible that ‘attend to’ does as well. Supposing otherwise commits us to the idea that we can perceive and be conscious of a unicorn, but cannot attend to one. Second, the empirical results mentioned above show that ‘pay attention to’ patterns with ‘conscious of’ and a family of other phenomenal verbs in terms of its existential entailments: all of these verbs can be used to report what is going on in cases of hallucination. Third, again there are coordination arguments that make it plausible that ‘attend to’ patterns with these verbs. I can consciously perceive a unicorn, and I can attend to what I perceive. Therefore I can attend to a unicorn. Together, these considerations make it plausible that ‘attend to’ has a notional reading. If so, it may be true that you are attending to what you are conscious of even though there is nothing such that you are conscious of, or attending to, it.

To illustrate how this disarms Smith’s argument, consider the analogous point in the case of other ITVs. Mary expects a storm, and Bill hopes for what Mary expects. It does not follow that there is a storm such that Mary expects it and Bill hopes for it; there may be no relevant storm at all. If so, all that is true is that both Mary’s expectation and Bill’s hoping are characterized, in Forbes’s sense, by the same property.

The same thing holds in the case of consciousness and attention. As Smith in effect points out, it may be that (11) is literally true in the hallucinatory case:

-

(11)

Henry is attending to what he is conscious of—namely, a tomato.

But if both ‘attend to’ and ‘conscious of’ have notional readings, then (11) can be true even if there is no theme such that Henry is conscious of or attends to that theme. Attention, like consciousness, is a state that can be characterized by a property without there being some object—of any type—that serves as its theme. Once again, therefore, an argument that seemed to support P1-R in fact only supports P1-N.Footnote 24

5.2 The case for P2 revisited

What about P2? As we saw above, the argument for this principle is founded on the premises, first, that if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is either a particular or a property, and, second, that if there is something of which you are conscious in an hallucination, it is neither a particular nor a property. Once we draw the distinction between P2-R and P2-N, however, this argument supports only P2-R. For consider again the reason for holding the second premise: there are no candidate particulars or properties to serve as the direct object or theme of your hallucination. This provides good reason to believe P2-R, but no reason at all to believe P2-N, since it gives no reason to deny that hallucinations are characterized by properties. Indeed, on our view, what is distinctive about hallucinations is that they are conscious states which lack themes, which is just what the argument for P2 shows.

6 From ‘consciousness’ to consciousness

The overarching lesson of our discussion may be now summarized as follows. The notional reading of ‘conscious of’ is used to report how states of perceptual consciousness are characterized, and so can be used to express the principle that all conscious states are characterized by a property. By contrast, the relational reading of ‘conscious of’ is used to specify the themes of conscious perceptual states, and so can be used to express the principle that some conscious states—hallucinations—lack themes. However, if hallucinations are states of perceptual consciousness that are characterized by properties but lack themes, these principles are not in tension. This is our solution to the presentation problem.

We’ll now conclude the discussion by addressing two issues that have so far been in the background. The first concerns the way in which ours is a proposal in the metaphysics of mind and not simply a proposal in semantics about the expression ‘conscious of’; the second concerns what to say about alternative solutions to the presentation problem.

As regards the metaphysical issue, we may start by noting the general sense in which semantic proposals can be converted into non-semantic proposals. In general, if ‘Henry is conscious of a red and round thing’ is true, then we may immediately infer that Henry is conscious of a red and round thing. In view of the nature of truth, in other words, it is always open to us to move from ‘consciousness’ to consciousness and vice versa; indeed, we have already exploited this point several times in the discussion above.

When we say that we are making a metaphysical proposal, as opposed to a semantic one, however, we are not relying on these general points about truth; nor do we mean that we can read off the nature of psychological states from our theories of linguistic phenomena. Rather, our suggestion is that the semantic proposal provides us with a candidate metaphysical view, which can then be evaluated on its own merits independently of linguistic concerns.

What is this candidate view? A convenient way to illustrate it is by seeing our proposal as a development of, and a corrective to, an influential metaphysical picture of conscious states. We may think of this picture as having three elements. Element 1 is that when you are in a state of consciousness of any sort, you are aware in a certain way of something: conscious states are in this sense constitutively tied to awareness. Element 2 is that in being aware of something, you bear a relation to something non-psychological, though the precise category or nature of this non-psychological thing is left open by the picture—it may for example be either a particular or a property.Footnote 25Element 3 is that the distinctive features of conscious states—their phenomenology, their rational and causal role, and their intentional character—are closely tied to the previous two elements: the state of awareness that you are in whenever you are conscious, as well as the non-psychological things to which you are related in being in that state.Footnote 26

There is much to say about this general picture, but for us the important point is that, in the light of what we have said, it may be understood in two very different ways. On the thematic version of the picture, as we will call it, conscious states are essentially thematic: they are essentially states that have non-psychological particulars or properties as their themes. So on this view, the three elements just mentioned come to this: first, when you are in a conscious state, you are in a state of awareness that has a theme; second, the theme in question is non-psychological; third, the philosophically interesting properties of conscious states bear close explanatory connections to these facts. A proponent of this version of the view need not deny that conscious states may have other properties too—for example, they might be characterized by something non-psychological. The point instead is that what makes something a conscious state is that it is a state of awareness of a certain kind that has something non-psychological as its theme.

On the non-thematic version of the picture, by contrast, conscious states are not essentially thematic. Rather, on this view, the three elements of the picture come to this: first, when you are in a conscious state, you are in state of awareness that is characterized by a property; second, the property in question is non-psychological; third, the philosophically interesting properties of conscious states bear close explanatory connections to these facts. A proponent of this version of the view need not deny that conscious states may have other properties too—for example they might have non-psychological themes. The point instead is that it is not necessary that they do: what makes something a conscious state is that it is a state of awareness of a certain kind that is characterized by a non-psychological property.

It might be objected that the non-thematic version of this picture is impossible, since to be aware of something is to have that thing as its direct object or theme. But this overlooks that our general story about ‘conscious of’ and ‘attends to’ applies equally to ‘aware of’: the same arguments that establish that ‘attend to’ is intensional suffice to show that ‘aware of’ is intensional. That ‘aware of’ is an ITV is predicted by the constitutive connection just noted between consciousness and awareness as well as by the connection between awareness and perception, and supported further by the experimental results discussed above. So, just as we may distinguish between conscious states that have themes and those that don’t, so we may distinguish states of awareness that have themes and those that don’t.

One might also suspect that, since characterization has appeared only as a thematic role in our neo-Davidsonian semantics, it has no metaphysical counterpart. But this is not so. For a state to be characterized by a property is for that state to have certain correctness conditions. For example, for a state of awareness to be characterized by the property of being a tomato is for it to be correct just in case one is relationally aware of a tomato. Of course, there remain certain foundational questions about what makes it the case that non-thematic states of awareness are characterized by the properties they are, but these are issues that we will set aside.

Clearly the thematic and the non-thematic versions of the awareness picture have a lot in common. Both proceed from a plausible conceptual connection between consciousness and awareness. Both assume that conscious states consist in relations to something non-psychological. And both assume that interesting functional, phenomenal and intentional features of consciousness are closely connected to these facts.

But the difference between them is that the thematic version of the awareness picture runs headlong into the presentation problem, while the non-thematic version avoids that problem. If you assume that conscious states are states of awareness that necessarily have non-psychological themes, the problem arises as to how to explain the fact that, in hallucinatory cases, there is no candidate to be the theme. In effect, that is the heart of the presentation problem. If you reject that assumption, by contrast, which is an option that becomes available in the light of what we have said, you are in position to solve that problem.

7 The alternatives

What finally of the alternatives to our proposal? The first thing to say is that it is a mistake to assume that our proposal stands in opposition to such well-known views in philosophy as representational and relational theories of perception; it is available to both, at least in principle. If characterization is construed as a fundamental, representational notion that is present in veridical perception as well as hallucination, then our proposal can be seen as a species of non-propositional representationalism. But if characterization is seen only as an account of hallucination, as opposed to a fundamental common element of both veridical and hallucinatory perceptual states, then our view can be seen as a species of disjunctivist relationalism, in particular a species of positive disjunctivist relationalism.Footnote 27

If classical positions of this sort may agree with our proposal, what positions deny it? Our view entails that, when Henry hallucinates a tomato, (a) he is conscious of a red, round thing; (b) the state he is in has no theme; and (c) the state he is in is characterized by a property. Any alternative to our view must therefore deny at least one of these claims.

But any such move is prima facie implausible. To deny (b), and insist that the state Henry is in has a theme, confronts the point we made above, namely that there is simply no good candidate to be the theme. Of course, proponents of the view that hallucinations have themes have suggested complex ways to avoid this point.Footnote 28 But for us these moves are unnecessary. If hallucinations have no themes, it is unsurprising that there are no good candidates to be their themes.

One might agree with us about themes but nevertheless deny (c), saying that Henry’s state is not characterized by a property. But this requires giving some account of what that state is. The dominant suggestion here is to say that Henry is in a state with propositional content: just as one can have a belief whose content is that there is a tomato three feet away, so one can be in a conscious state whose content is that there is a tomato three feet away.Footnote 29

However, even if Henry is in a state with propositional content, this is insufficient to solve the presentation problem. A key element of that problem, which we have been emphasizing, is that it is formulated using transitive verbs, or adjectival phrases with the same semantic function, such as ‘conscious of’, ‘attend to’ and so on. These constructions, at least on their face, do not accept propositional arguments. When we ask what a subject is conscious of in an hallucination, the question demands a noun phrase as an answer. But the propositional view does not offer us any such noun phrase. Might a friend of the propositional view suggest that the notional reading of apparently transitive verbs such as ‘conscious of’, ‘aware of’, and ‘attend to’ have propositional analyses? As a general semantic proposal, this is highly implausible: very few intensional transitive verbs appear to admit of straightforward lexical decompositions into propositional attitude expressions.Footnote 30

What finally of the claim that (a) is false, and so that Henry is not conscious of something red and round? This claim is defended by Adam Pautz (2007), for example, who writes:

In hallucination we sensorily entertain a proposition or perhaps a complex property. This gives us the vivid impression that we are aware of items of some kind. But this impression is mistaken. Pautz (2007, p. 519)

But the problem with this view, as Pautz is well aware, is that it denies the obvious. On the face of it Henry is conscious of a red, round thing, and he can attend to what he is conscious of. To try to deny this, as Pautz does, is very steep hill to climb.

Of course this isn’t sufficient to reject Pautz’s view; indeed nothing we have said here is sufficient to reject any alternative to our view. What we have tried to do, however, is point out that there are enough problems with these alternatives to motivate a looking elsewhere. Our suggestion here has been that ’conscious of’ is an ITV, and when this idea is transposed from language to metaphysics, a better view emerges.

Notes

The problem goes also by ‘the problem of perception’ and the ‘the problem of hallucination’ in the literature. See Crane and French (2016) for further discussion.

Syntactically, ‘conscious of’ and ‘aware of’ are not transitive, nor are they verbs; they are adjective + preposition pairs that relate a subject to a prepositional argument. But in the literature on intensional transitive verbs, and transitivity more generally, it is common to treat V + P and Adj + P combinations that relate two arguments as lexemes that function, semantically, as transitive verbs, as with ‘proud of’, ‘upset at’, ‘sorry about’, and ‘interested in’, among many others (see Forbes (2006, p. 36), Nebel (2019)). Indeed, the neo-Davidsonian framework that we will employ here treats these constructions in nearly identical ways. In light of this semantic similarity, in what follows we will refer to the expressions we are interested in, such as ‘conscious of’, as verbs. But nothing in our arguments turns on this. We could just as soon have called them ‘adjectives taking prepositional arguments’.

While to our knowledge no one in the philosophy of perception has argued that ‘conscious of’ itself is an ITV, the idea that some perceptual verbs are ITVs, and the associated idea that the objects of hallucination are intentional objects, is not new. This point was made first by Anscombe (1965) and then echoed by Harman (1990). However, while what Anscombe and Harman say is suggestive, neither provides a plausible semantics for ITVs, nor do they use such a semantics to address the question of what we are conscious of in a hallucination, as we will below.

Here and throughout, we are concerned only with states of perceptual consciousness—i.e. veridical perception, hallucination, visual imagination and illusion—rather than conscious states of other kinds.

In subsequent formulations of these principles, we will omit the material specifying that ‘you’ denotes the subject of the state.

As we read her, Schellenberg (2016) presents a similar argument.

Even Dretske (1999), who defends this view, agrees that it seems implausible. He writes:

This last claim [that we are aware of uninstantiated properties] may sound false—at least controversial. ...Isn’t awareness of properties (colors, shapes, sizes, orientations, etc.) always (and necessarily) awareness of objects having these properties? Dretske (1999, p. 106).

See also Fish (2009, pp. 22–23).

Quine (1956) indicates that the distinction between notional and relational readings is one of scope. However, in more formal settings, one’s account of the distinction depends on the semantic framework one adopts, and how it treats the interaction of scope and type. For instance, Montague (1974) derived the notional and relational readings using a mechanism that involved both scope and type. As we will see below, the neo-Davidsonian framework we adopt treats the distinction as one in the type of a verb’s thematic role.

In the text we modify Forbes’s view so that it fits with the more liberal definition of a property given Sect. 2.2, and so connects with the issues in the philosophy of mind and perception we are discussing. Forbes’s actual view is that Char is a relation between an event and a generalized quantifier. For our purposes, this amendment will make no difference. Whether modified or unmodified, the key difference between the form of the notional reading and that of the relational reading is the type difference between Theme and Char. Crucially, however, this difference in type does not entail that the verb ‘seek’ is lexically ambiguous, for it denotes one and the same property of events in (3) and (4), namely search(x). This single property is just accompanied by different argument structure in the two cases.

We grant, however, that this is not the only approach to the semantics of special quantifiers. Sainsbury (2018, Ch. 2) offers a competing, substitutional account of the semantics of ‘something’, as it occurs in the complement of an ITV on its notional reading.

Author (2020) presents a detailed empirical case for the intensionality of ‘perceives’. ‘Perceives’ contrasts with ‘see’ and ‘hear’, which plausibly have only relational readings.

The data and analysis from this experiment is available upon request.

An anonymous referee suggests a dilemma for our view. On the one hand, if enough speakers of English recognize that ‘conscious of’ has a notional reading, then they will recognize that ‘something’ as used in P1 is a special quantifier, in which case the presentation problem isn’t a compelling problem in the first place. On the other hand, if enough speakers fail to recognize such a reading, then there will be no such reading, and our proposal is unfounded. Our response is to deny this last claim. We think it is possible—perhaps even common—for a verb to have intensional features that go widely unrecognized, at least within a particular linguistic community. On our view, there is a legitimate strand of ordinary English usage in which ‘aware of’ and ‘conscious of’ have notional readings, but this strand has been largely overlooked by philosophers of mind and perception. This is why Anscombe’s famous discussion of the intensionality of sensation was anything but trivial. More generally, detecting the features of intensionality, and so detecting special quantifiers and distinguishing them from and non-special quantifiers, is not an easy task, even for competent speakers of a language.

On most standard approaches to the semantics of intensional transitive verbs, different verbs are associated with different kinds of conditions: searches have success conditions, fears realisation conditions, and desires with satisfaction conditions. We here use ‘correctness’ to designate the conditions appropriate to the case of ‘conscious of’, but importantly, we do not think that correctness is a notion reserved for propositional states.

It is important to bear in mind that, as we said above, the states of consciousness with which we are concerned here are states of perceptual consciousness.

Importantly, :(10) provides only a sufficient condition for the correctness of a non-thematic conscious state. Analogously, (5) provides only a sufficient condition for the success of a search. In defining characterization in this way, we follow Forbes (2006, p. 100).

Here our proposal is similar to one of the proposals made by D’Ambrosio (2019). But our proposal differs from his in several ways. First, we focus on ‘conscious of’ and related verbs, while he focuses on ‘perceives’ and ‘senses’. The former verbs are the ones at issue in the presentation problem. Second, D’Ambrosio treats characterization as a kind of modification in the course of developing a form of adverbialism. But as we will see later, our view, while consistent with adverbialism, is also consistent with other positions in the philosophy of perception. Finally, as we will see below, we are concerned with advancing a metaphysical view that serves as a corrective to an influential picture of the nature of conscious states; D’Ambrosio does not address this point at all.

In the passage quoted above, Smith talks of attending to an element of what one is aware in a hallucination. We think that this poses no further problem. Plausibly, the entire event of experiencing is characterized by a complex property built up from simpler ones. To focus on one element or aspect of the hallucinated scene is simply to enter into a state characterized by one of these subproperties. Likewise, to peruse or attend to the elements of the scene is to enter into a state of attention characterized by such subproperties.

It is important to bear in mind that our discussion is limited to perceptual consciousness, which we assume here and throughout is restricted to outer perception. On some views, introspection is a form of inner perception, consideration of which would require us to modify this component of the picture we are considering. Here we will set this complication aside.

For discussion of positive and negative disjunctivism, see Martin (2002, 2004) and Fish (2009). The positive disjunctivist offers an account of the nature of hallucination, whereas the negative disjunctivist says only that it cannot be discriminated from veridical perception. In providing an account of hallucination in terms of characterization by a property, our account is consistent with the former. It is also worth noting that if characterization is understood as a form of modification, as it is in D’Ambrosio (2019), our proposal can be accepted by the adverbialist as well.

For a defense of uninstantiated properties as themes, see Johnston (2004, §8).

The view is a common one in the literature; see Searle (1983), Millikan (2000, 2004), Byrne (2009), and Siegel (2010a, 2010b), among many others. We can even formulate the propositional view in our neo-Davidsonian framework by introducing a new thematic role for propositions: the Content role, which specifies the role that propositions play in states denoted by propositional attitude verbs. For accounts of this sort, see e.g. Pietroski (2005), Forbes (2018), and Yli-Vakkuri and Hawthorne (2018).

See Zimmermann (1993), Forbes (2006, Ch. 3), Montague (2009), Grzankowski (2016), and Forbes (2018), which we take to be representative of the consensus view on the semantics of ITVs. Further, for an argument that propositional decomposition of a range of intensional verbs is impossible, see Szabó (2003). For a dissenting opinion, see Larson et al. (1997) and Larson (2002).

References

Ali, R. (2018). Does hallucinating involve perceiving? Philosophical Studies, 175(3), 601–627.

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1965). The intentionality of sensation: A grammatical feature. In R. J. Butler (Ed.), Analytic Philosophy (pp. 158–180). Blackwell Publishers.

Barkasi, M. (2020). Some hallucinations are experiences of the past. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 101(3), 454–488.

Bealer, G. (1982). Quality and concept. Clarendon Press.

Broad, C. D. (1927). Scientific thought. Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner, and Co, Ltd.

Byrne, A. (2009). Experience and content. The Philosophical Quarterly, 59(236), 429–451.

Crane, T., & French, C. (2016) The problem of perception. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

D’Ambrosio, J. (2019). A new perceptual adverbialism. Journal of Philosophy, 116(8), 413–446.

Dretske, F. (1999). The mind’s awareness of itself. Philosophical Studies, 95, 103–124.

Fish, B. (2009). Perception, hallucination, and illusion. Oxford University Press.

Forbes, G. (2006). Attitude problems. Oxford University Press.

Forbes, G. (2018). Content and theme in attitude ascriptions. In A. Grzankowski & M. Montague (Eds.), Non-propositional intentionality. Oxford University Press.

Forrest, P. (2005). Universals as sense-data. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 71, 622–631.

Foster, J. (2000). The nature of perception. Oxford University Press.

Grzankowski, A. (2016). Attitudes towards objects. Noûs, 50(2), 314–328.

Harman, Gilbert. (1990) The intrinsic quality of experience. Philosophical Perspectives, 4: Action Theory and the Philosophy of Mind: 31–52.

Johnston, M. (2004). The obscure object of hallucination. Philosophical Studies, 120(1–3), 113–183.

Larson, R., den Dikken, M., & Ludlow, P. (1997). Intensional transitive verbs and abstract clausal complementation. SUNY at Stony Brook, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Larson, R. K. (2002). The grammar of intensionality. In G. Peter & G. Preyer (Eds.), Logical form and language (pp. 228–262). Oxford University Press.

Malcolm, N. (1984). Consciousness and causality. In D. M. Armstrong & N. Malcolm (Eds.), Consciousness and causality: A debate on the nature of the mind, great debates in philosophy. Basil Blackwell.

Martin, M. G. (2002). Particular thoughts & singular thought. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, 51, 173–214.

Martin, M. G. F. (2004). The limits of self awareness. Philosophical Studies, 120, 37–89.

Masrour, F. (2020). On the possibility of hallucinations. Mind, 129(515), 737–768.

Millikan, R. (2000). On clear and confused ideas. Cambidge University Press.

Millikan, R. (2004). Varieties of meaning. MIT Press.

Miracchi, L. (2017). Perception first. Journal of Philosophy, CXIV, 12, 629–677.

Moltmann, F. (1997). Intensional verbs and quantifiers. Natural Language Semantics, 5(1), 1–51.

Moltmann, F. (2003). Nominalizing quantifiers. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 32, 445–481.

Moltmann, F. (2004). Nonreferential complements, nominalizations, and derived objects. Journal of Semantics, 21, 1–43.

Moltmann, F. (2008). Intensional verbs and their intentional objects. Natural Language Semantics, 16, 239–270.

Moltmann, F. (2015). Quantification with intentional and with intensional verbs. Quantifiers, Quantifiers, and Quantifiers: Themes in Logic, Metaphysics, and Language, 141–168

Montague, M. (2009). Against propositionalism. Noûs, 41, 503–518.

Montague, R. (1974). Formal philosophy: selected papers of Richard Montague. Yale University Press.

Moore, G. E. (1903). The refutation of idealism. Mind, 12(48), 433–453.

Nebel, J. M. (2019). Hopes, fears, and other grammatical scarecrows. Philosophical Review, 128(1), 63–105.

Parsons, T. (1990). Events in the semantics of English. MIT Press.

Pautz, A. (2007). Intentionalism and perceptual presence. Philosophical Perspectives, 21, 495–541.

Pietroski, P. (2005). Meaning before truth. In G. Preyer & G. Peters (Eds.), Contextualism in philosophy (pp. 253–300). Oxford University Press.

Price, H. H. (1933). Perception. Robert W. McBride and Co.

Quine, W. V. (1956). Quantifiers and propositional attitudes. The Journal of Philosophy, 53(5), 177–187.

Richard, M. (2000). Semantic pretense. In A. Everett & T. Hofweber (Eds.), Empty names, fiction, and the puzzles of non-existence (pp. 205–232). CSLI Publications.

Sainsbury, R. M. (2005). Reference without referents. Oxford University Press.

Sainsbury, R. M. (2018). Thinking about things. Oxford University Press.

Schellenberg, S. (2016). Perceptual particularity. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, XCIII, 1, 25–54.

Searle, J. R. (1983). Intentionality. Cambidge University Press.

Siegel, S. (2010). Do experiences have content? In B. Nanay (Ed.), Perceiving the world. Oxford University Press.

Siegel, S. (2010). The contents of visual experience. Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. D. (2002). The problem of perception. Harvard University Press.

Szabó, Z. G. (2003). Believing in things. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 584–611

Tye, M. (2014). What is the content of a hallucinatory experience? In B. Brogaard (Ed.), Does perception have content? Blackwell.

Tye, M. (2014). Transparency, qualia realism and representationalism. Philosophical Studies, 170, 39–57.

van Geenhoven, V., & McNally, L. (2005). On the property analysis of opaque complements. Lingua, 115(6), 885–914.

Vendler, Z. (1957). Verbs and times. The Philosophical Review, 66(2), 143–160.

Yli-Vakkuri, J., & Hawthorne, J. (2018). Narrow content. Oxford University Press.

Zimmermann, T. E. (1993). On the proper treatment of opacity in certain verbs. Natural Language Semantics, 1, 149–179.

Zimmermann, T. E. (2006). Monotonicity in opaque verbs. Linguistics and Philosophy, 29, 715–761.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Alex Grzankowski, Alan Hájek, Zoltán Gendler Szabó, M.G.F. Martin, two anonymous reviewers for this journal, and an audience at the Oxford Mind Visiting Speaker Seminar.

Funding

Funding provided by ARC Grant DP170104295: The Language of Consciousness

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that they have no conflicting interest.

Ethical approval

There is no experimental data associated with this manuscript and no ethics approval needed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

D’Ambrosio, J., Stoljar, D. Perceptual consciousness and intensional transitive verbs. Philos Stud 180, 3301–3322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-023-01992-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-023-01992-w