Abstract

The growing body of literature on partnerships has paid most attention to their implications at the macro level, for society, as well as the meso level, for the partnering organisations. While generating many valuable insights, what has remained underexposed is the micro level, i.e. the role of managers and employees in partnerships, and how their actions and interactions can have an effect on the spread and potential effectiveness of collaborative efforts. This article uses a case-study approach to empirically explore the patterns and potential boundary conditions of so-called ‘trickle effects’ of partnerships among individual actors within and outside partnering companies, which have thus far only been proposed conceptually. Based on interviews with employees from three different companies, we found an evidence of trickle-down and trickle-up effects with higher and lower management, as well as trickle-round effects with colleagues, family, friends and customers. The article discusses several partnership characteristics that seem to play a role, and notes implications for research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The past decade has seen a wave of studies on partnerships, and a concomitant set of overview articles (e.g. Austin and Seitanidi 2012a, b; Selsky and Parker 2005), special issues (e.g. in Journal of Business Ethics, May 2009 and July 2010) and a research handbook (Seitanidi and Crane 2013). Most attention has been paid to the macro, societal implications of partnerships, and to the meso level, to the partnering organisations in the various stages of their collaboration, from formation and implementation to outcomes. While this has generated many valuable insights, what has remained underexposed is the role of individuals in partnerships and how their actions and interactions can have an effect on the spread and potential effectiveness of collaborative efforts.

It is here that this article seeks to contribute, in line with Austin and Seitanidi (2012b) who recommended further research at the micro level of partnerships, to obtain more insight into the potential so-called ‘trickle effects’ of these social interactions at the individual level, as proposed by Kolk et al. (2010). Focusing on managers and employees within organisations, they conceptually suggested partnership interactions to ‘trickle down’ (from managers to employees), ‘trickle up’ (from employees to managers) and/or ‘trickle round’ (between employees); the latter, horizontal effects may also extend from employees to people outside the organisation, for example, family, friends and customers (Kolk et al. 2010; cf. Austin and Seitanidi 2012b). Empirical research on these aspects has been scarce, except for anecdotal evidence and preliminary studies on trickle effects from employees to consumers and interactions with partner organisations (Le Ber and Branzei 2010; Vock et al. 2013). This article aims to shed light on the micro-level interactions by employees of organisations involved in collaborative activities and the related trickle effects.

Besides a contribution to the partnership literature, our study also adds to the corporate social responsibility (CSR) debate. With regard to the implementation of CSR programmes, extant research has suggested the need for a balance between top-down and bottom-up approaches (Van der Voort et al. 2009), and a more employee-centred perspective (Nord and Fuller 2009). Similarly, studies point at employees as potential advocates of CSR initiatives to external audiences (Bolton et al. 2011; Du et al. 2010; Dawkins 2004). However, current insights are mainly based on the views and (best) practices of (CSR) managers (e.g. Bolton et al. 2011; Maon et al. 2009; Seitanidi and Crane 2009; Sharp and Zaidman 2010; Van der Voort et al. 2009), not on actual perceptions and (inter)actions of employees, which have hardly been investigated. This raises the question whether and, if so, when employees are willing and likely to participate in and advocate CSR initiatives, which is a necessary condition to ensure their viability. Our study takes this perspective and aims to extend past research on CSR which advocated employee-centred approaches by exploring how such strategies may work.

Building on the conceptual framework by Kolk et al. (2010), this article unravels the patterns of trickle effects (i.e. trickle-up, trickle-down and trickle-round), as well as potential boundary conditions. While previous research pointed at the managerial importance of actively engaging employees in corporate social initiatives, this study provides implications for ‘how’ to do that. It also contributes to the broader CSR debate, by responding to recent calls for more research on individuals’ perceptions, actions and interactions, particularly through qualitative studies, to help reveal behavioural mechanisms, and thus shed light on the so-called microfoundations (Aguinis and Glavas 2012).

Given the lack of empirical research, we used a case-study approach to explore the issues raised above. Before explaining this further in relation to the methodological set-up of the study, the next section will first discuss the theoretical insights, specifically considering the role of employees in relation to trickle effects of partnerships, followed by a presentation of the findings. The article concludes with a discussion of our findings and implications for research and practice.

Employees and Trickle Effects

In partnerships’ trickle effects, employees seem crucial as they interact with managers, colleagues as well as customers, family and friends. Spreading the word about partnerships from within organisations has been suggested as a critical success factor by academics (Berger et al. 2006) as well as by practitioners, who identified a lack of effective communication and management as major obstacles for the creation of enthusiasm among a company’s internal and external constituents (C&E 2010; Tennyson and Harrison 2008). Some authors (Burmann et al. 2009; Burmann and Zeplin 2005) have, more generally, noted the importance of employees as facilitators and possible proponents of implementation and communication of brand and company activities, also vis-à-vis a range of external stakeholders. And according to a recent global citizen survey, 50 % of respondents regard ‘regular employees’ as highly credible in providing information about a company, a score similar to representatives of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and much higher than chief executive officers (CEOs) or government officials/regulators (Edelman 2012).

From a more internal, organisational perspective, employees have also been mentioned as important stakeholders of companies’ responsibility efforts (e.g. Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Du et al. 2010), but in most cases to highlight that CSR can help to retain current employees and attract new ones (Albinger and Freeman 2000; Turban and Greening 1997). In this regard, CSR is noted to increase pride in the company, as well as organisational commitment, job satisfaction, work motivation, loyalty, productivity and helping behaviours, and to lower absenteeism and turnover intentions (e.g. Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Brammer et al. 2007; Koh and Boo 2001; Peterson 2004). However, as Bolton et al. (2011, p. 64) observed, this is seen as a “by-product of CSR activity rather than an integral part of the process” in which the employee would be crucial to its success and considered the key (internal) stakeholder. Van der Voort et al. (2009) also noted a lack of attention for these internal “activists” in view of a dominant focus on managers.

Hence, despite the recognised importance, explicit study of the active role of employees in CSR, let alone partnerships, has been limited. Although recent publications have started to pay attention to the implementation of corporate social initiatives, these are often based on the views and current (best) practices of (CSR) managers (e.g. Bolton et al. 2011; Maon et al. 2009; Seitanidi and Crane 2009; Sharp and Zaidman 2010; Van der Voort et al. 2009), while the actual perceptions and (inter)actions of employees have remained relatively uncharted. In the case of partnerships, Berger et al. (2006) explored the positive effects for employees, considering intra- and interorganisational identification as well as community and relationship building. And Seitanidi (2009) also examined employees, but only of NGOs, showing the missed opportunities due to their too limited involvement in all stages of the partnership.

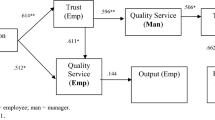

Participation in the planning and implementation of corporate social initiatives has been said to meet employees’ specific needs better than more centrally planned top-down initiatives (Bhattacharya et al. 2008). This moves beyond employee awareness only to active involvement of employees, which enables them to sometimes even act as ‘co-creators’ who can help spread the word to others, both within and outside their organisation. In the context of partnerships, a conceptual framework has been suggested recently, which looked not only at their more traditional top-down (‘trickle-down’) effects in organisations, but also at the bottom-up (‘trickle-up’) effects, and, horizontally, ‘trickle-round’ effects from employees to colleagues and to family, friends and customers outside the organisation (Kolk et al. 2010). Figure 1 gives an overview of these possible effects, with employees at the centre, and serves as starting point for this study to help shed light on the microfoundations of partnerships, focused on interactions between individuals. The vertical (trickle-up and trickle-down) and horizontal (trickle-round) effects will be briefly explained below, building on theoretical insights from the broader CSR literature, as input for the subsequent analysis and discussion of the findings.

Trickle-Down and Trickle-Up Effects

Originally derived from particularly economics and marketing (Evans 1989; Sheth and Parvatiyar 2001; Trigg 2001), the notion of trickle effects was introduced in the context of partnerships to highlight the various (sometimes indirect and more subtle) ways in which individual (inter)actions can spread within and beyond organisations (Kolk et al. 2010). In the management and CSR literature, most attention has traditionally been paid to internal effects, and particularly those from (higher level) managers to employees in a top-down fashion. Some authors have pointed at the need for a balance between top-down and bottom-up approaches, and for more research on this topic to increase our understanding of the complexities of organising CSR (Van der Voort et al. 2009). Nord and Fuller (2009, p. 282) emphasised a simultaneous consideration of “[c]entralization and decentralization” to improve organisational processes in dynamic environments, such as CSR. They called for an “employee-centred perspective”, different from previous approaches with a predominant focus on CSR as driven from the top downwards.

Important top-down drivers that have been suggested in the literature for the successful implementation of corporate social initiatives include the communication of strategies, values and beliefs from CEOs and higher-level managers to employees, to help create a joint organisational interpretation (e.g. Collier and Esteban 2007; Maon et al. 2008; Reed II et al. 2007; Waldman et al. 2006). Means that are available to companies to share values and information are top-down communication channels, including corporate websites, intranet, annual financial and CSR reports, e-mails, posters or flyers (e.g. Du et al. 2010). Moreover, leaders can use personal contacts, formally (e.g. during work meetings) or informally (e.g. during coffee breaks). Observing one’s direct leader’s displayed values and behaviours with regard to companies’ activities, particularly if leaders openly talk about the importance, may stimulate engagement (Kolk et al. 2010). Moreover, organisational support more generally, for example in the form of resources or rewards, has been mentioned to spur the institutionalisation of CSR programmes (e.g. Maon et al. 2009).

In addition to these aspects that can be explored as trickle-down effects, several CSR studies have stressed bottom-up approaches (e.g. Bolton et al. 2011; Maon et al. 2009; Van der Voort et al. 2009). Employees might be asked to act as ambassadors or advocates of a programme, or contribute ideas with regard to design and implementation, which may favourably impact employees’ sense of ownership (Maon et al. 2009). Attention has also been paid to the importance of giving employees a say regarding CSR, as this may enhance their support and cause more enduring effects (e.g. Appels et al. 2006; Hemingway and Maclagan 2004; Maclagan 1999). Particularly in the field of (company-supported) volunteering, employees have even been perceived as “activists” in their attempts to mobilise others in the organisation to participate in programmes (Van der Voort et al. 2009). These effects can trickle up, to managers, but may as well, and perhaps even more, trickle-round, to direct colleagues and other employees.

Trickle-Round Effects

Different from the ‘vertical’ line inherent to trickle-up and trickle-down effects, trickle-round effects are horizontally oriented, thus without hierarchical relationships, and involve interactions both internally with colleagues, and externally with customers, family and friends. Several authors have suggested that employees can have a valuable role in spreading the word about CSR. Bolton et al. (2011, p. 67) referred to employees as co-creators who may translate brand meanings to diverse contexts, thereby strengthening the appeal to various global and local audiences, both internally and externally. Du et al. (2010) mentioned the breadth of employees’ external social ties, which should not remain untapped in companies’ efforts to diffuse awareness and engagement in CSR initiatives. And Dawkins (2004) noted that employees should not be underestimated as a communication source towards external audiences, due to their high credibility as an informal channel. Her opinion poll results showed that one-third of employees had recommended a company to others if it acted responsibly; they were found equally likely to advise others against an irresponsible company.

Despite these assertions, research on the actual trickle-round effects of employee partnership interactions has been scarce, most notably for family and friends. There is some anecdotal evidence as well as preliminary empirical explorations, usually customer-oriented. Most specifically focused on partnerships’ trickle-round effects is the experimental study by Vock et al. (2013), which suggested that employees’ beliefs and behaviours regarding a partnership, such as being enthusiastic or volunteering for the partnership, may spill over to customers. In terms of word of mouth, Vlachos et al. (2010) found that salespersons’ perceptions of a company’s motives to engage in a partnership (i.e. values-driven versus egoistic-driven) influenced their trust in the company, which in turn affected their willingness to recommend it to others. Korschun et al. (2011) indicated that employees’ participation in a cause, and their perception that customers share their interest in CSR, increased their customer orientation.

And although it has been suggested that “companies should ‘tune up’ their internal CSR communication strategy and find ways to engage employees and convert them into companies’ CSR advocates” (Du et al. 2010, p. 14), it is not yet clear to what extent and how this could be achieved, and which factors might play a role, particularly in the case of partnerships. These are issues that are addressed in our exploratory study, considering trickle-down, trickle-up and trickle-round effects.

Research Approach

This study uses a case approach to explore trickle effects of partnerships as perceived by employees and key factors that seem to play a role in this regard. As this is a relatively new phenomenon, we aim to discover relevant factors and mechanisms involved in the micro-level interactions identified on the basis of existing literature (see the preceding sections and Fig. 1). The goal of our study is not only to identify patterns of trickle effects (i.e. trickle up, trickle-down, and trickle-round), but also potential boundary conditions which may explain when and why these effects occur. Therefore, we included several companies with variation in the type of partnership activities and related employee involvement. This requires relatively pro-active companies in the field of CSR in general and partnerships in particular. We conducted interviews with employees from three companies, including the CSR/partnership programme managers. We also scrutinised publicly available documents, such as websites, and annual financial and CSR reports.

Our approach was to refine and help develop existing theories and conceptual frameworks, and confront the evolving case phenomenon with evolving frameworks through a process of systematic combining (cf. Dubois and Gadde 2002; Kovács and Spens 2005). The inclusion of several case studies was meant to “analyze the variation among them” (Dubois and Gadde 2002, p. 558) and to obtain more insight into potential boundary/organisational conditions that play a role. By detecting similarities and differences across cases, we gained a better understanding of our findings. The sampling of interviewees and informant choice was driven by the research question rather than by representativeness (Brunk 2010; Miles and Huberman 1994; Öberseder et al. 2011). The underlying rationale was that respondents participated in the programmes, including a variety of possible forms of engagement, such as donating money, contributing knowledge or skills, representing the partnership inside the company, or participating in an activity.

We applied reputational case selection, in which interviewees are selected prior to data collection based on the recommendation by key informants (Miles and Huberman 1994), in our case the companies’ programme managers. We interviewed 32 individuals, which is considered to be sufficient for this purpose (McCracken 1988) (for more details see the next section and the Appendix). We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews, mainly face-to-face and incidentally by telephone. All interviews were recorded with respondents’ permission and transcribed; anonymity was guaranteed.

The interview guideline, which was based on our conceptual framework, started with a few general questions about the respondent and the company, followed by specific ones regarding her/his awareness of and participation in the programme, including potential sources of information and communication and organisational support and involvement. Furthermore, we asked for their views of relationships and interactions with others (see Fig. 1). Of the respondents, ten also had (some) supervisory tasks but often only a few subordinates and not directly concerning other interviewees. In the few cases where the line management role was substantial and interviewees were able to say something about this top-down relationship that added to the analysis, we included their views. Regarding the trickle-round effects, we asked all interviewees with whom they talk about the programmes, both internally and externally, with the latter including customers if applicable for the respondent’s function.

The analysis followed established principles of qualitative research. In an iterative process, we started with carefully reading the transcripts, coding and interpreting the results. The initial codes, which were based on our literature study and are thus derived deductively, were higher-level management/organisational support, direct superiors, colleagues, family/friends and customers. Where applicable, these categories were subdivided into the following codes: trickle-up, trickle-down and trickle-round effects (from and to employees). The same codes were applied for the three companies. When re-reading the transcripts, additional codes were identified inductively, which we used to subdivide broader codes into more specific categories and themes. Examples of these codes are as follows: representative/ambassador, motivation/benefits, attributions, opinion about partnership, fit, awareness (information sources), participation, corporate relations, timing and type of partnership activities. In our analysis, we looked for patterns and similarities among respondents and the three companies, as well as for emerging differences. For the interpretation of differences between the cases, we considered information on organisational characteristics (cf. Tables 1, 2).

Sample

Our interviews took place in three international companies headquartered in the same country but operating in different sectors: insurance, logistics and electronics. They are engaged in a variety of CSR efforts which they communicate according to the A + guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative. Based on publicly available documents, as indicated above, as well as meetings with the CSR/partnership programme managers, we put together Table 1 with key information for each of the three cases. It shows an interesting variation regarding the type of partnership and the activities involved, as well as the level of strategic fit between the company’s core business and the cause. Below we give more details for each of the three companies.

The insurance partnership evolved from the strategic goal set by the board of directors to become a leader in micro-insurance in developing countries. To this end, the company cooperates with several partners to help organisations that offer micro-insurance to professionalise their services. Selected employees of the company are encouraged to actively participate in the micro-insurance programmes by contributing knowledge and core business-related skills. The company facilitates participation by providing paid work time to employees. However, the number of participants is restricted to teams of only a few employees per business unit, who are selected in consultation with the human resource management department. Participants usually conduct field trips to developing countries and their performance is evaluated in the framework of their management development programme. The analysis includes eight interviewees, one of whom with line management responsibilities (see Appendix).

The logistics partnership was initiated by the company’s former CEO, and covers a broad range of activities in support of a United Nations programme, including use of the company’s airplanes for emergency food deliveries, financial support by the company and its employees, who have initiated a variety of fundraising activities throughout the years, and knowledge transfer about logistical issues. To increase awareness and participation in the programme among employees, self-selected representatives (so called ‘ambassadors’) are allowed to spend a certain amount of their paid work time on the programme. Due to the variety of activities in which the logistics employees can participate (compared to insurance and electronics), a larger sample for this company seemed appropriate and turned out to be feasible. Of the 17 persons included, six had supervisory tasks.

The electronics company collaborates with local public organisations (i.e. schools). During an annual one-day event, volunteers of the company collaborate with teachers of primary schools to educate children on topics such as light, water, air and hygiene, aimed at improving pupils’ health and well being. Moreover, employees upgrade the lighting in the schools they visit for free, using the company’s products. The programme has a global scope and is carried out in various countries in which the company operates. Employees can sign up to participate in the programme and local ‘coordinators’ are assigned to coordinate contacts with the partnering local schools. Our analysis includes seven interviews, and three interviewees have line management responsibilities; one of them, however, turned out to have no familiarity with the programme.

Findings

Below we will present the findings, distinguishing, as in the literature section, subsequently trickle-down and trickle up effects (vertical) and trickle-round effects (horizontal). Within these two categories, we analyse the various lines as included in Fig. 1, focusing on employees and their perceptions. Illustrative quotes from company respondents are used; these were translated into English by the authors. Where possible, we try to link findings to the peculiarities of the partnerships as identified in Table 1 (e.g. in terms of fit and types of activities). Furthermore, attention is paid to cross-cutting themes that also emerged from the literature and that we included in the interviews, regarding information and communication, and organisational support and involvement. Table 2 summarises key aspects for the three companies that will return in the analysis and discussion.

Trickle-Down and Trickle-Up Effects

Higher-Level Management

The three programmes were introduced at the corporate level and thus implemented as a top-down approach. However, visibility of higher-level management differs across the companies. For logistics, particularly the former CEO was visible in the media and in company reports, and identified by employees as the initiator of the partnership. Programme participants of insurance, however, refer to corporate strategy more generally, or to specific higher-level managers who visibly support the programme, for example, by giving interviews about micro-insurance or by being present at related events. Like insurance, respondents of electronics are either not aware of higher-level management involvement, or refer to specific members of the management team who actively participated as programme coordinators. Overall, it seems that the direct impact of higher-level managers on employees is very limited, and seems to neither drive nor hamper respondents’ willingness to participate in the programmes.

Nevertheless, employees of all three companies acknowledge higher-level indirect support and facilitation of the programmes, which becomes visible in several ways. For example, interviewees mention that a dedicated function has been created for the programme manager, for which the company makes funds available to facilitate and finance activities, and that it provides work time for participants:

It also costs a fortune to send me there for three months. They still have to pay my salary, for example, and that all costs money. (Employee Logistics)

Well I think that they (top management) are very positive, because otherwise we would not pay so much attention to it and invest so much money. (Employee Insurance)

Support by higher-level management, whether directly or indirectly visible, can be regarded as a top-down approach. Bottom-up approaches from lower to higher hierarchical levels, however, emerged as important during the interviews as well, but only for insurance and logistics. The difference for the electronics case might be due to its more limited fit, concerning one specific division, and/or the fact that activities concerned only one day a year (see the overview of the characteristics in Table 1). All bottom-up initiatives mentioned by employees were in line with the overall partnership strategy and often required higher-management support or facilitation. Examples are employees suggesting the adoption of a new micro-insurance project, or ‘ambassadors’ of logistics who require managers’ support for the realisation of an information campaign or fundraising activity within company premises.

You experience that employees themselves are starting up initiatives, for example, to collect some money; that happens quite regularly. (Ambassador Logistics)

We can easily approach her (the programme manager) with initiatives, so it’s really a two-way flow. (Another Ambassador Logistics)

(Direct) Line Management

Most interviewees describe their direct superior generally as supportive of the programmes. Superiors value the (personal) learning opportunities for representatives who participate in a mission abroad, which is particularly the case for micro-insurance, which is closely related to the company’s core business and part of its management development programme (see Table 2).

He [immediate superior] believes it is awesome, incredibly good that we do this. On the one hand from the perspective of corporate social responsibility, and on the other hand, from the perspective of employee development. And then specifically also my own personal development. (Employee Insurance)

One superior of insurance even refers to the business case of the programme in the long run in relation to support for employees’ involvement. Leadership support also becomes visible indirectly, for example through managers who help representatives to inform colleagues about the partnership (e.g. by helping them to spread information materials or by addressing programme-related issues during work meetings), or who enable and facilitate employees’ active participation (e.g. by allowing them to spend work time on the programme). While respondents acknowledge their superior’s role in facilitating or permitting participation, they agree that superiors have little impact on their awareness and motivation to participate.

If he had absolutely opposed it then I would have had another problem. But my motivation does not depend that much on my supervisor, no. I think it is more about your own intrinsic motivation. (Employee Insurance)

Well, it’s not that they really stimulate it. It’s just that they don’t put the slightest obstacle in your way if you participate. (Employee Electronics)

Despite this overall support, critical comments are frequently made as well, but only for insurance and logistics, and particularly concerning employees who spend some time on a mission abroad. Employees mention top-down pressures and a lack of issue ownership on the part of lower-level managers. They perceive superiors to be torn between top-down expectations with regard to the programme and overall (generic) performance expectations.

If somebody comes by with an idea regarding CSR […] so it is not you who came up with it […] it is simply imposed on you by the executive board, that’s what’s actually happening. No manager is happy with that, really nobody. (Employee Insurance)

If the director of the division is committed and agrees that we do that project, well then there should not be a manager at a lower level who tries to cancel or block the whole thing.(Another Employee Insurance)

While these factors seem to be less important in the case of the one-day community event of electronics, respondents also mention the difficulty of combining their participation with busy work schedules, and superiors’ conflict between allowing participation of their entire team and safeguarding the flow of work.

Among our respondents, those with a clear leadership function mostly acknowledge their active role regarding the diffusion of the programmes among employees. However, they also assign responsibility to employees. Managers who regard it as their responsibility to stimulate the diffusion of the programme often refer to their role as a manager more generally, likely indicating top-down trickle effects of perceived organisational norms and values:

So if you have such a responsible position as I do, then it is part of the job to motivate people, and make sure that, in case they are not socially involved, you at least try to encourage them in that direction. (Manager Logistics)

However, rather than acting as a role model or actively stimulating employee participation, many managers prefer to leave the decision whether to participate in activities or not to employees themselves:

Let’s say, we receive standard information by e-mail from the company about the partnership, so everyone has received that […] and the usual mailings that I post on the information board, but beyond that I believe it’s everybody’s own responsibility. (Manager Logistics)

It should not be the case that I push this, it should be something that people are proud of otherwise it doesn’t make much sense. (Another Manager Logistics)

Overall, the freedom to choose whether to actively participate or not resonates with most respondents from logistics and electronics, who associate obligatory participation with instrumental motives of the company.

I heard about another case in which the manager had said ‘I registered all of you’. If my manager had done that, well… I believe that would have been ridiculous.” (Employee Electronics)

Because I notice […] that some managers use it in the discussions about employee engagement […] Then it starts to look as if there is double meaning, and I think that is really not appropriate.” (Another Employee Electronics)

This is different for insurance, where participants are evaluated with regard to their performance in the micro-insurance programme by their superiors during regular appraisals. As participation in the programme is integrated into employees’ management development trajectory, such evaluations by superiors are considered to be acceptable.

Hence, while we see several trickle-down and trickle-up effects, it seems that higher-level and line management provide a more generic supportive context, mostly through the initial decision, and the resulting organisational set-up and structure of the partnership (see Table 2), but less in the subsequent implementation process as experienced by employees. In that sense, management-driven downward influences may be more indirect than assumed (cf. Maon et al. 2008), or only in the early stages. Considering interviewees’ remarks about intrinsic motivations, supervisors may need to be careful in ‘putting pressure’ on their employees. That is, an involvement needs to be balanced with respect to possible rewards given to employees for participation (see e.g. Maon et al. 2009) and other organisational requirements imposed on (line) management (e.g. efficiency or profit). This difficult balancing act requires more detailed study (cf. Aguinis and Glavas 2012), also considering the broader dynamics in relation to communication within the organisation, both vertically and horizontally, amongst employees.

Trickle-Round Effects

Colleagues

In insurance and logistics, representatives (i.e. micro-insurance participants, and ambassadors or employees who participated in a mission abroad), are identified as an important source of partnership information and engagement. According to representatives themselves, their role is to create awareness, enthusiasm and pride, and to facilitate employee engagement. Moreover, thwarting scepticism by advocating the programme’s effectiveness is another role mentioned by respondents. This seems to be particularly the case for representatives who went on a mission abroad. It is important for them to demonstrate that they were not on a pleasure trip, and to prove that the money collected by (employees of) the organisation is effectively used for the purpose:

I found it very important that it was not some sort of jaunt, and that I really did something, and really conveyed something, and brought something back to the people here. And that they [colleagues] too did not think, ‘well, [he or she] spent a week on the beach’. (Ambassador Logistics)

The micro-insurance activities do not concern some people, and they think ‘oh, there [he or she] goes again, one week vacation’…oh well… (Employee Insurance)

The importance of this function is confirmed by other employees’ critical remarks about the perceived effectiveness of sending representatives on a mission abroad, and about the effectiveness of the partnership more generally. For electronics, the role of the programme coordinators is different. Rather than creating awareness, enthusiasm and pride, they describe their primary function as coordinating schools and participating employees, and encouraging additional employee engagement where necessary.

There are considerable differences in the way in which companies try to raise awareness and engagement for the partnerships, as shown especially in their internal communication (see Table 2), a crucial element mentioned in many studies discussed above (e.g. Burmann and Zeplin 2005; Du et al. 2010; Kolk et al. 2010). Communication within insurance turned out to be highly organised: participants are the central node from where information is disseminated horizontally, bottom-up, and subsequently top-down through various communication departments. This differs from logistics, where representatives (ambassadors) have less control over the information that reaches employees due to the breadth of the partnership, which includes a variety of activities and projects. Rather than initiating all partnership-related activities and communication materials themselves, ambassadors deliberately filter the information they receive from partnership managers, by judging items according to their relevance and suitability for employees in their divisions (top-down).

As an ambassador I believe that it is my task to say ‘okay, we are not going to do anything with it [the partnership] for now’, if you feel that people are not interested during that particular period. You really have to choose the right moments to pass on information. It should neither be too much nor too little, it should be at the right moment, otherwise people won’t be open for it. (Ambassador Logistics)

In addition, however, they also initiate employee engagement activities within their divisions, which are often related to fundraising, and which sometimes require support from higher-level management (horizontal and bottom-up). In the case of electronics, communication about the community day is mainly centralised (top-down), which may result in horizontal communication between employees at different levels of the organisation. For insurance and logistics, personal contact with representatives seems to spur employees’ awareness, interest and active involvement in the programme. Knowing a colleague who, for instance, went on a mission abroad often results in questions regarding the purpose of the programme, and the participant’s personal experiences. Moreover, participants often rolled into the programme by helping other participants.

When I said ‘I will go to India’, it went like a wildfire. There was a lot of talk about it. I am working for a department of 400 people, well I believe that at least 350 of them know that we are going to India. (Employee Insurance)

Especially when you know someone who has been there it is fun. (Employee Logistics)

While personal contact among employees is important to stimulate employee engagement in electronics as well, contact with the programme coordinators is of less importance. Rather, employees regard engagement as a team-building exercise which often depends on their colleagues’ engagement as a group, which emerged as an important driver for participation. Hence, while there are various trajectories of communication, also depending on the type of programme (fit, frequency of activities and involvement; see Table 1), the realisation of horizontal communication (see Table 2) seems important.

Family and Friends

Almost all respondents have at least mentioned the respective programme to family and/or friends. Employees’ motivations for talking about it are often rooted in representatives’ active participation in the programme, or in their desire to establish a favourable image of the company externally. First, a higher level of participation, particularly spending some time on a mission abroad, seems to increase the likelihood of talking about the programme. Second, the programme provides employees with an interesting topic to talk favourably about the company, or their work. Their willingness to advocate the programme seems to be related to pride evoked by the company’s social responsibility efforts, and also appears to be stronger in case of family members or friends with an affinity or assumed interest in the topic.

I think it makes it easier to talk about your work […]. And at the same time people believe it is interesting because it is in a country far away. So it is somewhat easier, the threshold is somewhat lower to tell others what [the company] is actually doing. (Employee Insurance)

Often [the respondent talks about the logistics partnership] with people from the same logistics sector, yes, also partly to show ‘Look, you can think that you [as a company] are active in this, but we also do this and that’. (Employee Logistics)

Participants of electronics, for example, mainly talk about the programme with their children, family members who live close to the schools where the one-day event took place, or friends with children. Interestingly, communication flows about the three programmes are bi-directional, as evidenced by questions received by respondents after having participated.

A factor that emerged from the interviews with regard to the kind of word of mouth, i.e. negative or positive, is perceived external prestige (PEP), which describes “the way in which employees believe outsiders see their organization” (Kim et al. 2010, p. 561). Our findings suggest that employees’ opinions about the programmes are often in line with the perceived opinions of family members or friends. Despite some critical perceptions, respondents’ stated PEP regarding the three programmes is predominantly positive.

Favourable PEP: “When telling my friends about it, or when I am at a party or so, they are all really impressed and are like, wow, that’s special.” (Employee Logistics)

[Employee talks about the programme] in my sports club, with my friends, with my family, and they would say ‘oh, how nice that you are allowed to do that’. (Employee Electronics)

Unfavourable PEP: “[…] questions they ask: (a) do you really believe that it’s helpful, functional? And (b) don’t you think it is a bit two-faced, how should I say it, hypocritical, to exhibit the ‘do-gooder’ while there is little impact? […] Well, I must admit that to some extent I do understand what they say, and I agree with it.” (Employee Insurance)

Interestingly, some respondents who are confronted with critical remarks by family members or friends seem to act as advocates or ‘reputation shields’ (Bhattacharya et al. 2008) of the company and try to adjust the negative image.

I definitely tell my view of the story, of course. […] But it is exactly the same as in my daily work. There I have to convince all kinds of people that we are going to sell new products […] and then everybody always says that this is not going to work out, or that it’s nonsense, this will only cost money. (Employee Insurance)

And if you are with your family, you also behave as a representative. You have a very responsible job and you automatically consider it […] The way I act outside [the company] and how I think about these kinds of projects is influenced by, maybe not 100 %, but maybe 60–70 % by the job I have. (Employee Logistics)

Where possible, employees also try to engage family members or friends in programme-related activities, particularly fundraising in the case of logistics, which is often combined with sociable or entertaining events. For instance, family members and friends donate money or participate in awareness events, soccer games or quizzes, with part of the proceeds being donated to the cause. Also in the case of electronics, respondents try to link their participation to their private lives by selecting schools attended by their children.

Customers

Employees of the three companies state that awareness of the programme’s existence among customers is generally low, although several respondents of insurance and logistics believe that important corporate relations are familiar with it to at least some extent. While respondents of insurance expect the programme to be communicated more actively to external contacts when it will be more established, employees of logistics and electronics refer to an informal policy restricting active communication about it externally.

When they initiated [the partnership], they told us ‘We are not going to boast about it. We are not going to use it in presentations, we are not going to use it in sales pitches, we will just do it’. (Employee Logistics)

Nevertheless, there is some evidence for corporate communication towards customers in all three companies, such as on the corporate website, in CSR reports or through the media (e.g. visibility of the CEO advocating the programme). Furthermore, although no ready-made materials seem to be available to be spread among company customers, respondents of insurance and logistics—but not of electronics—state that many key accounts are informed upon employees’ own initiative. For example, respondents mention the inclusion of information material in tender offers, sending brochures or talking about the programmes on the phone or during customer visits. Moreover, some employees even encourage corporate relations to participate by asking them to donate money or goods. In two cases from logistics and electronics, spill-over effects of the programmes to a client’s and supplier’s organisation, respectively, were noted by respondents.

Occasionally, account managers from [the company’s] corporate relations [department] contact their key business accounts and tell them about it because they think that it differentiates us in the market, and that it is a way to build customer loyalty. (Employee Insurance)

It is rather the case that if large companies have been doing business with us for a longer period of time, or if we are working on a real big project, it is occasionally mentioned. Then we see how they might be able to contribute. However, usually they are not informed at all, that is a real pity for us. (Ambassador Logistics)

Respondents are divided with regard to whether programmes should be communicated to customers or not. Those in favour of external communication refer to potential positive effects on the corporate image, and the possibility to improve existing relationships with key accounts. Several others, however, hesitate whether external communication might be a good idea, or add certain conditions, such as that it has to be sincere and subtle rather than instrumental to attract customers, and that external communication should only take place based on a significant corporate contribution to the programme first.

In my opinion, it is not something to boast about […] I believe it is something really great and it seems to me that indeed you can tell your customers about it. (Employee Logistics)

Let’s first do some things, and then you can start telling others about it. Ideally we want that others start talking about our activities. (Employee Insurance)

I liked that they said ‘We will communicate as little as possible about it’[…] and I actually feel that they could have paid more attention to it, because it remained extremely low-profile. (Employee Electronics)

Whether respondents are willing to advocate programmes to customers also seems to depend on customers’ demonstrated interest in the societal issue, and the level of fit between the programme and the company’s core business, which emerged as important during the interviews, and as suggested in the literature (Berger et al. 2004; Vock et al. 2013). Customers (or suppliers) of the companies proactively ask about corporate responsibility efforts, particularly in the context of tender enquiries, indicating bi-directional communication. Participants of insurance can easily link micro-insurance to the company’s core business, which makes it interesting for their customers, and strengthens the message that the company aims to convey, according to our respondents. The close link also seems to improve their understanding of the underlying meaning of insurance, which makes the company’s core business more tangible, and frequently results in story-telling about the origin of insurance. A perceived lack of interest among customers or fit between the societal issue and the core business, however, seems to restrain employees from advocacy engagement, which became apparent for logistics and electronics.

People often ask what [the company] is doing with regard to corporate social responsibility. For that purpose we simply produce a piece of text which can be sent out as part of tender offers […]. Because if we tell customers this story, well, this story is certainly much better than if you talk about recycled cups. I wouldn’t say that this is not important as well, but a project that directly fits with the core business is certainly interesting to mention in such a context. (Employee Insurance)

I cannot really imagine that I send out an offer and that I add a brochure of the [partnership], mentioning that we are a sponsor. I can’t really picture it yet. (Ambassador Logistics)

Respondents’ perceived lack of interest and of strategic fit for logistics becomes even more apparent when respondents talk about the company’s environmental responsibility programme (e.g. reducing its carbon footprint), which is seen as more closely linked to the company’s core business, and which is an important topic for their customers as well.

[The partnership] is not interesting for our customers […]. Carbon footprint, CO2 reduction, that’s what’s interesting for them, eh, corporate social responsibility more generally, but especially this [the partnership] is really an internal issue in my view. We also do not actively communicate it externally. (Sales Manager Logistics)

This statement also hints at another topic that emerged from the interviews, namely the added value for the customer to be derived from such corporate activities. Interestingly, potential customer benefits are only mentioned for programmes that are closely related to the company’s core business, such as improved products due to employees’ learning experiences with the micro-insurance project, or lower-emission transportation, which is considered as important for winning tenders in logistics.

One of the decision criteria in tenders is the level of CO2 emissions. Look, then you really have a story. […] you can cash with your client because you receive revenue. But [the partnership], I have difficulties translating it into financial or customer value. (Sales Manager Logistics)

In addition to customers, other corporate relations emerged as important stakeholders as well, particularly in the case of insurance, which engages in multi-stakeholder partnerships with other companies and local NGOs to set-up micro-insurance, potentially with the long-term goal to seize business opportunities as well:

So in terms of corporate relations it plays a role, almost unintentionally, as you meet companies with the same drive and the same way of thinking about social responsibility. And that’s good for our relations. (Employee Insurance)

Discussion and Conclusions

This article aimed to help shed light on the microfoundations of partnerships, i.e. the micro-level interactions by employees, in response to calls for more research on the role of individuals in the literature on partnerships, CSR and strategic organisation more generally. Studying employees adds a bottom-up approach to the more traditional top-down studies focused on managers in the area of CSR as well as partnerships. In view of the scarcity of empirical research, a case-study approach was used to explore the patterns of trickle effects of partnerships (trickle-down, trickle-up and/or trickle-round) from the perspective of employees, and key factors that seem to play a role in this regard. We interviewed employees in three companies headquartered in the same country, which showed variation in the types of activities undertaken in the framework of their respective partnerships as well as in the level of strategic fit between the company and the cause. Aspects concerning organisational support and involvement as well as communication and information provision were also studied, which appeared to play a role in the trickle effects that employees mentioned.

Considering the various micro-level interactions distinguished in Fig. 1, the following conclusions can be drawn. Starting with the trickle-down and trickle-up effects, higher-level managers and direct superiors are generally not perceived as very active in promoting the programmes across the three companies that we studied. Their direct influence on employees’ awareness of and motivation to participate thus seems rather limited (except for the former CEO of logistics). Nevertheless, indirect trickle-down effects emerged from the interviews. While higher-level management’s support becomes visible to employees through the provision of organisational resources and support structures (e.g. work time, money for travelling to projects), direct superiors are mostly acknowledged for facilitating and permitting employees’ active participation. Rather than actively stimulating participation from the top, managers are overall perceived as supportive towards bottom-up initiatives, which, however, were only identified in the case of the more strategic programmes (i.e. those from insurance and logistics). The lower level of activity in the case of electronics might be explained by the nature of the one-day event, which is centrally organised and communicated, and that offers relatively limited opportunities for employees to come up with their own initiatives.

While existing studies have stressed the importance of managers’ shared values and beliefs with regard to CSR, which need to be communicated throughout the organisation (Collier and Esteban 2007; Kolk et al. 2010; Maon et al. 2008; Reed II et al. 2007; Waldman et al. 2006), Van der Voort et al. (2009) mentioned that having higher-level managers as representatives of CSR programmes may raise scepticism among employees, who might perceive participation as management-imposed obligation rather than their own decision. Our findings suggest that managers may not necessarily need to act as role models and become actively involved in programmes themselves. However, respondents in our sample with clear management tasks saw it as their role as organisational leader to signal the importance of the topic for the corporate agenda by, for example, addressing partnership-related issues during work meetings. Whether different leadership styles make a difference in this regard (cf. Du et al. 2012; Groves and LaRocca 2011) deserves further attention. Moreover, it seems important that managers allow and facilitate employees’ own initiatives, also by providing necessary resources, which is particularly important if employees are made responsible for programme implementation. In the insurance case, for example, respondents point out the bureaucratic hurdles of starting up micro-insurance programmes at their own initiative, or they requested more support for the communication of their activities. A perceived lack of organisational support for bottom-up initiatives may lead employees to question management’s sincerity regarding the programme.

Concerning trickle-round effects within the organisation, our study suggests that employees can drive awareness and participation in the programmes. Peers, for example in the role of ambassadors or those who participated in partnership-related activities, may create enthusiasm and pride among colleagues, and even thwart scepticism. With regard to consumers, Bhattacharya et al. (2008) referred to this phenomenon as a ‘reputation shield’ towards hostile external constituents. We add to this notion by identifying this role for internal audiences as well. Interestingly, these roles seem to be less pronounced among employees of electronics, as they mainly adopt a task orientation, such as coordinating or implementing initiatives that are introduced top-down. These differences in behaviours towards peers could potentially be explained by employees’ motivations for or benefits derived from their engagement with the cause, which might be induced by the level of structural fit, which is more limited in the electronics case.

With regard to a company’s external audiences, findings support our expectations that employees talk about partnership-related activities, and their own participation in particular, with family members, friends and customers. Whether and to what extent employees talk with these audiences, however, seems to depend on the perceived interest or affinity of the external constituent with the issue. For family members and friends, employees’ perceptions of how external audiences think about the programme, referred to as PEP in the literature (e.g. Dutton et al. 1994; Kim et al. 2010), also appears to influence their willingness to talk either favourably or unfavourably about the programme. PEP impacts employees’ level of identification with the organisation and their self-concepts, which are more positive when employees perceive that external constituents’ views of the organisation are congruent with how they see themselves (Dutton et al. 1994). It hence seems important that organisations ensure a favourable image of partnerships among internal audiences first, as this might stimulate positive advocacy and thwart scepticism towards external audiences.

Overall, respondents seemed somewhat more hesitant to communicate about the programmes with customers, compared to family and friends. Having said that, it should be noted that not all our respondents have contact with customers. Instead, their answers may also reflect their views on whether the company should communicate the partnership to customers or not. While some acknowledge that this might be positive for the corporate image and improve customer relationships, they also stress that communication should be subtle and sincere, and that the company should act on its promises first. The willingness of customer-facing employees to talk about the programme with clients seems to depend on the level of fit between the company’s core business and the cause, or the potential benefits that customers may derive from the company’s partnership efforts. This notion provides valuable practical implications for managers, who may wish to ensure an appropriate level of strategic fit of their collaborative efforts upfront, and consider their customers’ potential interest in the partnership as well. Follow-up research based on more observations regarding the different fit types would be helpful to shed more light on this topic (cf. Vock et al. 2013). This also applies to further studies focused on customer-facing employees to consider whether partnerships can have a ‘branding’ effect, both internally and externally (cf. Burmann et al. 2009; Punjaisri et al. 2008).

In summary, our findings support and extend prior CSR publications which suggested that CSR programmes should be implemented by balancing top-down and bottom-up approaches, and by considering potential spill-over effects to external constituents as well (Bolton et al. 2011; Dawkins 2004; Kolk et al. 2010; Van der Voort et al. 2009). While these studies mainly adopted a managerial point of view, our research confirms the importance of the employees’ perspective and also identifies when such trickle effects may work. Our findings suggest that the likelihood of partnership programmes being diffused through trickle-up, trickle-down and trickle-round effects may depend on the specific characteristics of the activity. The programme’s support structure, the scope of employee engagement and the level of fit with core business seem particularly important in this regard. For example, a high level of fit between the cause and the company’s core business may increase the willingness of customer-facing employees to advocate the partnership among clients. Similarly, the higher the level of employees’ involvement in the programme, the more likely they seem to act as a reputational shield for the partnership vis-à-vis peers. These practical implications allow managers to carefully plan their partnership/CSR activities in alignment with the desired effects.

Despite the theoretical and practical contributions, our study has limitations as well. While we included three case studies rather than relying on a single company to increase variation, our sample size was still relatively limited. Obtaining access to more organisations with larger numbers of respondents would hence be beneficial to validate our findings statistically. This would also allow for quantitative (survey) approaches amongst the various types of actors that we identified. The inclusion of teams within organisations would enable the examination of the influence of leadership style and (managerial) values. Moreover, through the use of statistical methods on larger numbers of respondents and organisations, also from different countries and cultural contexts, the relative importance of the various trickle effects, and the role of company-specific, partnership-specific and actor-specific factors might be established. Nevertheless, in view of the scarcity of research in this field, we believe that this study provides a useful basis for future investigations on the microfoundations of partnerships.

References

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Albinger, H. S., & Freeman, S. J. (2000). Corporate social performance and attractiveness as an employer to different job seeking populations. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(3), 243–253.

Appels, C., van Duin, L., & Hamann, R. (2006). Institutionalising corporate citizenship: The case of Barloworld and its ‘employee value creation’ process. Development Southern Africa, 23(2), 241–250.

Austin, J. E., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2012a). Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 1: Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(5), 726–758.

Austin, J. E., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2012b). Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2: Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(6), 929–968.

Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2004). Social alliances: Company/nonprofit collaboration. California Management Review, 47(1), 58–90.

Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2006). Identity, identification and relationship through social alliances. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34, 128–137.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Sen, S., & Korschun, D. (2008). Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(2), 37–44.

Bolton, S. C., Kim, R. C.-H., & O’Gorman, K. D. (2011). Corporate social responsibility as a dynamic internal organizational process: A case study. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(1), 61–74.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719.

Brunk, K. H. (2010). Reputation building: Beyond our control? Inferences in consumers’ ethical perception formation. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 9(4), 275–292.

Burmann, C., & Zeplin, S. (2005). Building brand commitment: A behavioural approach to internal brand management. Brand Management, 12(4), 279–300.

Burmann, C., Zeplin, S., & Riley, N. (2009). Key determinants of internal brand management success: An exploratory empirical analysis. Brand Management, 16(4), 264–284.

C&E. (2010). Corporate-NGO partnerships barometer 2010. London: C&E.

Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(1), 19–33.

Dawkins, J. (2004). Corporate responsibility: The communication challenge. Journal of Communication Management, 9(2), 108–119.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 8–19.

Du, S., Swaen, V., Lindgreen, A., & Sen, S. (2012). The roles of leadership styles in corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics,. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1333-3.

Dubois, A., & Gadde, L.-E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55, 553–560.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 239–263.

Edelman. (2012). 2012 Edelman Trust Barometer: Executive summary.

Evans, M. (1989). Consumer behaviour towards fashion. European Journal of Marketing, 23(7), 7–16.

Groves, K. S., & LaRocca, M. A. (2011). An empirical study of leader ethical values, transformational and transactional leadership, and follower attitudes toward corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(4), 511–528.

Hemingway, C. A., & Maclagan, P. W. (2004). Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 50, 33–44.

Kim, H.-R., Lee, M., Lee, H.-T., & Kim, N.-M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee-company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 557–569.

Koh, H. C., & Boo, E. H. Y. (2001). The link between organizational ethics and job satisfaction: A study of managers in Singapore. Journal of Business Ethics, 29, 309–324.

Kolk, A., Van Dolen, W. M., & Vock, M. (2010). Trickle effects of cross-sector social partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(Supplement 1), 123–137.

Korschun, D., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Swain, S. D. (2011). When and how does corporate social responsibility encourage customer orientation? ESMT Working Paper. http://www.esmt.org/fm/479/ESMT-11-05.pdf.

Kovács, G., & Spens, K. M. (2005). Abductive reasoning in logistics research. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 35(2), 132–144.

Le Ber, M. J., & Branzei, O. (2010). (Re)Forming strategic cross-sector partnerships. Relational processes of social innovation. Business and Society, 49(1), 140–172.

Maclagan, P. (1999). Corporate social responsibility as a participative process. Business Ethics: A European Review, 8(1), 43–49.

Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2008). Thinking of the organization as a system: The role of managerial perceptions in developing a corporate social responsibility strategic agenda. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 25, 413–426.

Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2009). Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(Supplement 1), 71–89.

McCracken, G. (1988). The long interview. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expended sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nord, W. R., & Fuller, S. R. (2009). Increasing corporate social responsibility through an employee-centered approach. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 21(4), 279–290.

Öberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Gruber, V. (2011). “Why don’t consumers care about CSR?”: A qualitative study exploring the role of CSR in consumption decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 104, 449–460.

Peterson, D. K. (2004). The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business and Society, 43, 296–319.

Punjaisri, K., Wilson, A., & Evanschitzky, H. (2008). Exploring the influences of internal branding on employees’ brand promise delivery: Implications for strengthening customer–brand relationships. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 7(4), 407–424.

Reed, A, I. I., Aquino, K., & Levy, E. (2007). Moral identity and judgments of charitable behaviours. Journal of Marketing, 71, 178–193.

Seitanidi, M. M. (2009). Missed opportunities of employee involvement in CSR partnerships. Corporate Reputation Review, 12(2), 90–105.

Seitanidi, M. M., & Crane, A. (2009). Implementing CSR through partnerships: Understanding the selection, design and institutionalisation of nonprofit-business partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(Supplement 2), 413–429.

Seitanidi, M., & Crane, A. (Eds.). (2013). Social partnerships and responsible business: A research handbook. London: Routledge.

Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31(6), 849–873.

Sharp, Z., & Zaidman, N. (2010). Strategization of CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 93, 51–71.

Sheth, J. N., & Parvatiyar, A. (2001). The antecedents and consequences of integrated global marketing. International Marketing Review, 18(1), 16–19.

Tennyson, R., & Harrison, T. (2008). Under the spotlight. London: International Business Leaders Forum.

Trigg, A. B. (2001). Veblen, Bourdieu, and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Economic Issues, 35(1), 99–115.

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 658–672.

Van der Voort, J. M., Glac, K., & Meijs, L. C. P. M. (2009). ‘Managing’ corporate community involvement. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(3), 311–329.

Vlachos, P. A., Theotokis, A., & Panagopoulos, N. G. (2010). Sales force reactions to corporate social responsibility: Attributions, outcomes, and the mediating role of organizational trust. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(7), 1207–1218.

Vock, M., Van Dolen, W. M., & Kolk, A. (2013). Micro-level interactions in business-nonprofit partnerships. Business and Society,. doi:10.1177/0007650313476030.

Waldman, D. A., Siegel, D. S., & Javidan, M. (2006). Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1703–1725.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating organisations and interviewees, as well as Freke van Nimwegen and David Vethaak for their help with the implementation of this study; and the guest editor and reviewers for their constructive feedback on earlier versions of the paper. This article is one of the publications resulting from a long-term research programme on partnerships at the University of Amsterdam Business School; in recent years, some sub-projects were linked to the Partnerships Resource Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: List of Interviewees

Appendix: List of Interviewees

Company type | Line management responsibilities (yes or no) | Specificities regarding involvement in the programme, if any | Years of tenure in company | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Insurance | No | Participation in activities | 6 years | Female |

Insurance | No | Leads activities | 6 years | Male |

Insurance | No | Participation in activities | 6 months | Male |

Insurance | No | Participation in activities | 12 years | Male |

Insurance | No | Participation in activities | 4 years | Male |

Insurance | No | Participation in activities | 9 years | Male |

Insurance | No | Involved in selection | Not given | Female |

Insurance | Yes | Leads activities | 28 years | Female |

Logistics | No | Ambassador | 4 years | Female |

Logistics | No | Ambassador | 4 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Only heard about it | 3–4 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Knows about it | 11 years | Female |

Logistics | Yes | Knows about it | >10 years | Male |

Logistics | Yes | Participation in activities | 14 years | Male |

Logistics | Yes | Participation in activities | 8 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Participation in activities | 32 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Was ambassador | 19 years | Female |

Logistics | No | Knows about it | 40 years | Male |

Logistics | Yes | Knows about it | 19 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Ambassador | 15 years | Female |

Logistics | Yes | Knows about it | 20 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Knows about it | 4 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Knows about it | 23 years | Male |

Logistics | Yes | Knows about it | 8 years | Male |

Logistics | No | Only heard about it | 4 years | Male |

Electronics | Yes | Involved in coordination | 18 years | Male |

Electronics | No | Participation in activities | 6.5 years | Male |

Electronics | No | Participation in activities | 14 years | Female |

Electronics | Yes | Has participating staff | 17 years | Male |

Electronics | No | Participation in activities | 20 years | Male |

Electronics | No | Participation in activities | 37 years | Female |

Electronics | Yes | No familiarity with the programme | 33 years | Male |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolk, A., Vock, M. & van Dolen, W. Microfoundations of Partnerships: Exploring the Role of Employees in Trickle Effects. J Bus Ethics 135, 19–34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2727-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2727-9