Abstract

Most of us are familiar with the phenomenology of mental effort accompanying cognitively demanding tasks, like focusing on the next chess move or performing lengthy mental arithmetic. In this paper, I argue that phenomenology of mental effort poses a novel counterexample to tracking intentionalism, the view that phenomenal consciousness is a matter of tracking features of one’s environment in a certain way. I argue that an increase in the phenomenology of mental effort does not accompany a change in any of the following candidate representational contents: (a) representation of externally presented features, e.g. brightness, contrast, and so on (b) representation of task difficulty, (c) representation of the possibility of error, (d) representation of trying to achieve some state of affairs, (e) representation of bodily changes like muscle tension, or (f) representation of change in cognitive resource availability and lost opportunity cost. While tracking intentionalism about some phenomenal experiences like pains might obtain, it does not seem to obtain for all phenomenal experiences. This puts the intentionalist into an uncomfortable position of trying to explain why some phenomenal experiences have representational content and not others. Since many believe that tracking intentionalism or something like it provides the best chance of naturalizing consciousness, these arguments deserve detailed consideration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Supervenience relation characteristic of weak intentionalism is a natural starting point because (i) any stronger relationship between the two will entail the supervenience relation (e.g., if these two types of properties turn out to be identical, this will entail that the phenomenal at least supervene on the representational), and (ii) any hopes of giving a naturalistic account of phenomenal properties requires delineating which facts about mental state form the minimal supervenience base.

The supervenience claim could take one of various forms: (a) local versus global; and (b) intramodal versus intermodal. The first distinction concerns whether supervenience only holds for a certain class of mental states or for all mental states, e.g. whether it holds only for visual perceptual states or for all states including moods. The second distinction concerns whether supervenience holds only for pairs of states of the same sense modality, or for any random pair of states across modalities. Notably, as Speaks (2015) points out, these distinctions are a matter of degree. Since the modality of this phenomenology doesn’t allow straightforward delineation, the intramodal/intermodal distinction won’t provide any traction. For the same reason, since we are exploring a new type of phenomenology previously untouched in the debate, we are concerned with global rather than local intentionalism given that only global intentionalists promise to find a supervenience base for any pair of phenomenal experiences whatsoever.

First, TI reduces phenomenal states to intentional states, which in turn are explained in terms of the tracking relation of broadly physical properties and states if affairs. The reduction of intentionality to tracking enjoys recent popularity (Mendelovici and Bourget 2014).

Evidence for the gestalt function of attention could be found in studies showing that attention enhances the perception of low-level visual features including contrast (e.g., Carrasco et al. 2004).

Although the subjective ratings of mental effort were not the focus of the study, the validity of their measuring techniques has precedent in the empirical literature (Morsella et al. 2009). Specifically, to further explore the subjective dimension of cognitive effort, the Morsella et al. introduced the following paradigm for measuring subjective effects of interference. Subjects were trained to introspect the particular feeling associated with incongruent conditions of the Stroop task. This introspection training was done to ensure that “participants were introspecting the same thing during both flanker and Stroop tasks” (ibid, p. 10). The experimenters found more subjective effects for incongruent conditions than for congruent conditions. Furthermore, these changes in phenomenology were reported prior to changes in response time. Interestingly, the phenomenology itself proved almost ineffable to the subjects (ibid, p. 16).

Naccache et al. write that “Unexpectedly, control abilities of patient RMB evaluated in various versions of this Stroop tasks were amazingly preserved… we could see the presence of an efficient dynamic regulation of control abilities as indexed by Gratton and proportion effects” (ibid, p. 1319).

Mental flow states are characterized by the experience of mastery or feeling “in the zone”. For example, if playing a musical instrument and sight reading, the subject might be aware of how smoothly the experience is going. There might be associated feelings of control, i.e. being able to adjust to other players at short notice. In contrast, phenomenology of mental effort surfaces when one is aware that things are being presented smoothly, and yet there is an added awareness that it is costing some effort (even if you’re not quite sure how to “apply” it). (Csikszentmihályi 1992). Thus, it is the complete opposite of the experience of transparency.

I thank an anonymous referee for this suggestion.

Christensen et al. (2015) illustrate the nature of agentive phenomenology in professional mountain biking. They argue that complex action involves a complex parametric structure (p. 344). For example, the agent is (somewhat) aware that applying pressure to the bike brakes influences the “control parameter” to change the speed (“target parameter”), which in turn could influence another parameter (e.g. curvature around the turn). So, a skilled agent can navigate the upcoming sharp curve via manipulating the amount of pressure she applies in order to manipulate the speed needed to make the turn.

Recall that according to TI, representation is grounded in evolutionary histories. For example, pain experience tracks bodily damage and badness because it was selected to carry information about bodily damage and badness by reliably correlating with these features of the environment (Cutter and Tye 2011).

To review, Naccache et al. (2005) show that subjects’ attentional and cognitive mechanisms function normally in the absence of PME.

References

Aarts, H., Bijleveld, E., & Custers, R. (2010). Unconscious reward cues increase invested effort, but do not change speed-accuracy tradeoffs. Cognition, 115, 330–335.

Aarts, H., Bijleveld, E., Daunizeau, J., Veling, H., & Zedelius, C. M. (2012). Promising high monetary rewards for future task performance increases immediate task performance. PLoS ONE, 7, e42547.

Alkadhi, H., Brugger, P., Boedermaker, S. H., Crelier, G., Curt, A., Hepp-Reymond, M. C., et al. (2005). What disconnection tells about motor imagery: Evidence from paraplegic patients. Cerebral Cortex, 15, 131–140.

Baddeley, A. (1996). Exploring the central executive. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49, 5–28.

Bayne, T., & Levy, N. (2006). N. Sebanz & W. Prinz (Eds.), The feeling of doing: Deconstructing the phenomenology of agency in disorders of volition (pp. 49–68). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bicknell, K., Christensen, W., Mcllwain, D., & Sutton, J. (2015). The sense of agency and its role in strategic control for expert mountain bikers. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research and Practice, 2, 340–353.

Boghossian, P., & Velleman, J. D. (1989). Color as a secondary quality. Mind, 98, 81–103.

Botvinick, M., Carter, C. S., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001a). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108, 624–652.

Botvinick, M., Cohen, J. D., & Carter, C. (2004). Conflict Monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(12), 539–546.

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001b). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108, 624–652.

Bresler, C., & Laird, J. D. (1992). The process of emotional feeling: A self-perception theory. In M. Clark (Ed.), Emotion: Review of personality and social psychology (pp. 223–234). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bush, F. M., Francis, M., Harkins, S. W., Long, S., & Price, D. D. (1994). A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain, 56, 217–226.

Carrasco, M., Ling, S., & Read, S. (2004). Attention alters appearance. Nature Neuroscience, 7(3), 308–331.

Carter, C. S., & van Veen, V. (2007). Anterior cingulated cortex and conflict detection: An update of theory and data. Cognitive Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 367–379.

Cavallaro, L. A., Flack, W. F., & Laird, J. D. (1999). Separate and combined effects of facial expressions and bodily postures on emotional feelings. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 203–217.

Cohen, J. D., Dunbar, K., & McClelland, J. L. (1990). On the control of automatic processes: A parallel distributed processing account of the Stroop effect. Psychological Review, 97(3), 332.

Cramer, S. C., Lastra, L., Lacourse, M. G., & Cohen, M. J. (2005). Brain motor system function after chronic, complete spinal cord injury. Brain, 128, 2941–2950.

Critchley, H. D. (2003). Human cingulate cortex and autonomic cardiovascular control: Converging neuroimaging and clinical evidence. Brain, 216, 2139–2152.

Csikszentmihályi, M. (1992). Flow: The psychology of happiness. Rider. ISBN 978-0-7126-5477-7.

Cutter, B., & Tye, M. (2011). Tracking representationalism and the painfulness of pain. Philosophical Issues, 21, 90–109.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason and the human brain. New York: Gossett/Putnam.

Dehaene, S., Chengeux, J. P., & Kerzberg, M. (1998). A neuronal model of a global workspace in effortful cognitive tasks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95, 14529–14534.

Duclos, S. E., & Laird, J. D. (2001). The deliberate control of emotional experience through control of expressions. Cognition and Emotion, 15, 27–56.

Duclos, S. E., Laird, J. D., Schneider, E., Sexter, M., Stern, L., & Van Lighten, O. (1989). Emotion-specific effects of facial expressions and postures on emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 100–108.

Franconeri, S. L., et al. (2012). Flexible cognitive resources: Competitive content maps for attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(3), 134–141.

Hilbert, D., Klien, C., (2014). “No problem”. In R. Brown (Ed.), Consciousness inside and out: Phenomenology, neuroscience, and the nature of experience, studies in brain and mind (pp. 229–306). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hill, C. S. (2009). Consciousness. Nova York: Cambridge University Press.

Inzlicht, M., & Marcora, S. M. (2016). The central governor model of exercise regulation teaches us precious little about the nature of mental fatigue and self-control failure. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 656.

Keillor, J., Barrett, A., Crucian, G., Kortenkamp, S., & Heilman, K. (2002). Emotional experience and perception in the absence of facial feedback. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 8(1), 130–135.

Kellerman, J. M., & Laird, J. D. (1982). The effect of appearance on self-perceptions. Journal of Personality, 50, 296–351.

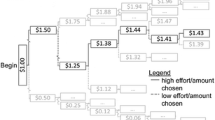

Kurzban, R., Duckworth, A., Kable, J. W., & Myers, J. (2013). An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36, 661–679.

LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Maringer, M., & Niedenthal, P. M. (2009). Embodied emotion considered. Emotion Review, 1, 122–128.

Maunsell, J. H., & Newsome, W. T. (1987). Visual processing in monkey extrastriate cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 10(1), 363–401.

Mendelovici, A., & Bourget, D. (2014). Naturalizing intentionality: Tracking theories versus phenomenal intentionality theories. Philosophy Compass, 9(5), 325–337.

Milham, M. P., Banich, M. T., Webb, A., Barad, V., Cohen, N. J., & Wszalek, A. F. Kramer. (2001). The relative involvement of anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex in attentional control depends on nature of conflict. Cognitive Brain Research, 12, 467–473.

Morsella, E., Wilson, L. E., Berger, C. C., Honhongva, M., Gazzaley, A., & Bargh, J. A. (2009). Subjective aspects of cognitive control at different stages of processing. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 71(8), 1807–1824.

Naccache, L., Dehaene, S., Cohen, L., Habert, M. O., Guichart-Gomez, E., Galanaud, D., et al. (2005). Effortless control: Executive attention and conscious feeling of mental effort are dissociable. Neuropsychologia, 43(9), 1318–1328.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihályi, M. (2014). The concept of flow. In Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89–105). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). Embodying emotion. Science, 316, 1002–1005.

Pautz, A. (2013). The real trouble for phenomenal externalists. In T. Brown (Ed.), Consciousness inside and out: Phenomenology, neuroscience, and the nature of experience (pp. 237–298). Belrin: Springer.

Prinz, J. J. (2005). Are emotions feelings? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 12(8–10), 9–25.

Sàenz, M., Buraĉas, G. T., & Boynton, G. M. (2003). Global feature-based attention for motion and color. Vision Research, 43(6), 629–637.

Speaks, J. (2015). The phenomenal and the representational. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Strack, F., Martin, L. L., & Stepper, S. (1988). Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: A nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 768–777.

Tye, M. (1995). Ten problems of consciousness: A representational theory of the phenomenal mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tye, M. (2006). The puzzle of true blue. Analysis, 66, 173–178.

Tye, M. (2008). The experience of emotion: An intentionalist theory (unpublished). https://webspace.utexas.edu/tyem/www/emotions.pdf.

van Veen, V., Cohen, J. D., Botvinick, M. M., Stenger, V. A., & Carter, C. S. (2001). Anterior cingulate cortex, conflict monitoring, and levels of processing. Neuroimage, 14(6), 1302–1308.

Wagenmakers, E. J., Beek, T., Dijkhoff, L., Gronau, Q. F., Acosta, A., et al. (2016). Registered replication report: Strack, Martin, & Stepper 1988. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(6), 917–928.

Westbrook, A., & Braver, T. S. (2015). Cognitive effort: A neuroeconomic approach. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, 395–415.

Acknowledgements

Many heartfelt thanks to people who have provided invaluable feedback on this paper, including Bernhard Nickel, Elizabeth Schechter, Casey O’Callaghan, Neil Levy, Alex Byrne, Wayne Wu, Ned Block, Edouard Machery, Jeff Speaks, Adam Pautz, generous conference commentators, and many others.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doulatova, M. Tracking intentionalism and the phenomenology of mental effort. Synthese 198, 4373–4389 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02347-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02347-x