Abstract

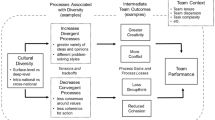

A lack of diversity remains a significant problem in many STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) communities. According to the epistemic approach to addressing these diversity problems, it is in a community’s interest to improve diversity because doing so can enhance the rigor and creativity of its work. However, we draw on empirical and theoretical evidence illustrating that this approach can trade on the epistemic exploitation of diverse community members. Our concept of epistemic exploitation holds when there is a relationship between two parties in which one party accrues epistemic benefits from another party’s knowledge and epistemic location and, in doing so, harms the second party or sets back their interests. We demonstrate that the ironic outcome of this nominal application of the epistemic approach is that it undermines the epistemic benefits which it promises. Indeed, we show that epistemic exploitation undermines the relationships and interactions among community members that produce rigor and creativity. Our central argument is that for communities to reap the benefits of an epistemic approach to diversity, to implement a genuine epistemic approach, they need to develop cultures that ameliorate the harms faced by, and protect the interests of, their diverse community members.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The research we draw on in this paper assumes a gender binary, as do the cultures we examine. But we want to acknowledge that this belies a more pluralistic reality. Focusing on cis men and women is not the only relevant or the most representative way to talk about gender diversity. However, we use cis language because it reflects the current state of much research and affairs in the academy. We intend, nevertheless, to extend our arguments in this paper to more inclusive sex/gender categories. Wherever relevant, we hope that readers will see the applicability and value of our insights here to folks who are traditionally excluded by binaristic, cis language.

For a fuller picture of the representation of women and people of color in STEM, see Ferguson 2013; Rollock, 2019; Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, 2017; Walkington, 2017 in addition to the National Science Board, 2018; the data from Statistics Canada in Wall 2019; and Dionne-Simard et al., 2016.

Although we focus on diverse and commonplace practitioners, it is possible there are goldilocks practitioners whose representation in an epistemic community is, roughly speaking, just right. Our focus on two kinds of practitioners, diverse and commonplace, does not assume that the social categories of interest are binaristic. We acknowledge that many of these categories are complex. For example, as we show later in this paper, differences in the representation and experiences of white women, Black women, and Latinas are important in different STEM communities.

See also Williams 2018.

It is possible for situational diversity, without accompanying epistemic diversity, to improve a community’s epistemic practices. For example, Phillips (2017) and Steel et al., (2021) explore the idea that the mere presence of a diverse practitioner in a group is, in some cases, correlated with commonplace practitioners being better epistemic agents—sharing dissenting views and more objectively considering the evidence and arguments available to them. The idea is that the mere expectation of epistemic diversity arising from situational diversity can lead commonplace practitioners to approach their knowledge-production practices more carefully. However, in this paper, rather than focusing on cases in which situational diversity can be beneficial on its own, we focus on cases in which the culture of epistemic communities impedes the development of effective epistemic diversity when diverse practitioners are present.

There can be times in the development of some ideas when they are best nurtured by a community of like-minded supporters, but according to this theory, at that point in development, they remain poorly justified. Once these ideas are developed, they require investigation by a diverse community to become better justified.

Thanks to Samantha Brennan for helping us clarify the relationship involved in our characterization of exploitation.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for helping us clarify this point.

Although the empirical and theoretical points we raise in the remainder of this section tend to focus on race and gender, we do not claim that this is an exhaustive description of factors supporting epistemic exploitation or that race and gender are the only axes of oppression that are relevant to epistemic exploitation.

We maintain, however, that some commonplace practitioners experience very few, if any, additional costs, beyond those which every practitioner must pay in order to be a member of an epistemic community.

According to Medina (2011), these disproportionate assignments of credibility contribute to many varieties of epistemic injustices that harm not only the direct victim(s) of the injustices but also their larger community (which shares with the victim(s) a collective or social imaginary).

See Saul (2013) for a more detailed analysis of how stereotype threat and implicit biases affect women in philosophy.

Henry & Glenn (2009) provide innovative ideas for Black women in the academy who have or had problems connecting and collaborating with others. Their discussion is informed by Black feminist thought and critical race theory.

See also Frye 1983 for a similar discussion about the unintentional objectification of researchers.

See Wylie et al., 2007 for a review of social science literature making this point.

See Heavy Head 2006 for a discussion of how Indigenous scholarship in Canada has been impeded, even when special efforts were made to encourage and support Indigenous scholarship.

References

Allen, W. R., Epps, E. G., Guillory, E. A., Suh, S. A., & Bonous-Hammarth, M. (2000). The Black Academic: Faculty Status among African Americans in U.S. Higher Education. The Journal of Negro Education, 69(1/2), 112–167

Altmann, J. (1974). Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour, 49(3), 227–267. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853974x00534

Anderson, E. (2020). Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 Edition). Edited by Zalta, E. N. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/feminism-epistemology

Arvin, M., Tuck, E., & Morrill, A. (2013). Decolonizing feminism: Challenging connections between settler colonialism and heteropatriarchy. Feminist Formations, 25(1), 8–34

Berenstain, N. (2016). Epistemic Exploitation. Ergo, 3(22), 569–590

Code, L. (1995). Rhetorical Spaces: Essays on Gendered Locations. Routledge

Code, L. (2008). Taking subjectivity into account. In A. Bailey, & C. Cuomo (Eds.), The Feminist Philosophy Reader (pp. 718–741). McGraw-Hill

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297–1338

Croizet, J. C., & Claire, T. (1998). Extending the concept of stereotype and threat to social class: The intellectual underperformance of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(6), 588–594

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2004). When Professionals Become Mothers, Warmth Doesn’t Cut the Ice. Journal of Social Issues, 60(4), 701–718

Dionne-Simard, D., Galarneau, D., & LaRochelle-Côté, S. (2016). Women in scientific occupations in Canada. Insights on Canadian Society (Statistics Canada). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2016001/article/14643-eng.htm

Dotson, K. (2011a). Concrete flowers: Contemplating the profession of philosophy. Hypatia, 26(2), 403–409

Dotson, K. (2011b). Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia, 26(2), 236–257

Dotson, K. (2012). How is this paper philosophy? Comparative Philosophy, 3(1), 3–29

Fehr, C. (2007). Are smart men smarter than smart women? The epistemology of ignorance, women and the production of knowledge. In A. M. May (Ed.), The ‘Woman Question’ and Higher Education: Perspectives on Gender and Knowledge Production in America (pp. 102–116). Edward Elgar

Fehr, C. (2011). What is in it for me? The benefits of diversity in scientific communities. In H. Grasswick (Ed.), Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science: Power in Knowledge (pp. 133–155). Springer

Ferguson, D. J. (2013). The Underrepresentation of African American Women Faculty: A Phenomenological Study Exploring the Experiences of McKnight Doctoral Fellow Alumna Serving in the Professoriate. University of South Florida Scholar Commons. Doctoral dissertation. Accessed at https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5680&context=etd

Fidell, L. (1970). Empirical verification of sex discrimination in hiring practices in psychology. American Psychologist, 25, 1094–1098

Frye, M. (1983). The Politics of Reality: Essays in Feminist Theory. The Crossing Press

Graff, G., Birkenstein, C., & Durst, R. (2018). They Say, I Say (4th edition). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc

Greenwood, M., de Leeuw, S., & Ngaroimata Fraser, T. (2008). When the politics of inclusivity become exploitative: A reflective commentary on Indigenous peoples, Indigeneity, and the academy. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 31(1), 198–207

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599

Haraway, D. (1989). Primate Visions: Gender, Race and Nature in the World of Modern Science. New York: Routledge

Haslanger, S. (2008). Changing the Ideology and Culture of Philosophy: Not by Reason (Alone). Hypatia, 23(2), 210–223

Heavy Head, R. (2006). Living in a world of bees: A response to Indian on the lawn, ed. Katy Gray Brown and Lorraine Mayer. APA Newsletter on American Indians in Philosophy (The American Philosophical Association), 5(2), 12–15

Henry, W., & Glenn, N. M. (2009). Black Women Employed in the Ivory Tower: Connecting for Success. Advancing Women in Leadership Journal, 27(2), 1–18

Hrdy, S. (1986). Empathy, Polyandry, and the Myth of the Coy Female. In R. Bleier (Ed.), Feminist Approaches to Science (pp. 119–146). Pergamon Press

Ivie, R., & Guo, S. (2006). Women Physicists Speak Again. American Institute of Physics. https://www.aip.org/statistics/reports/women-physicists-speak-again

Jenkins, F. (2013). “Singing the Post-Discrimination Blues.”. In K. Hutchinson, & F. Jenkins (Eds.), Women in Philosophy: What Needs to Change? (pp. 81–102). Oxford University Press

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Glynn, C. J., & Huge, M. (2013). The Matilda Effect in Science Communication: An Experiment on Gender Bias in Publication Quality Perceptions and Collaboration Interest. Science Communication, 35(5), 603–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012472684

Lorde, A. (1984). The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. In Lorde A., Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (2007 edition, pp. 110–114). Crossing Press

Longino, H. (1990). Science as Social Knowledge: Values and Objectivity in Scientific Inquiry. Princeton University Press

Longino, H. (2001). The Fate of Knowledge. Princeton University Press

Lugones, M. (1987). Playfulness, ‘world’-travelling, and loving perception. Hypatia, 2(2), 3–19

McGee, E. O., & Kazembe, L. (2015). Entertainers or education researchers? The challenges associated with presenting while black. Race, Ethnicity, and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2015.1069263

McPherson, D. H. (2006). Indian on the lawn: How are research partnerships with Aboriginal peoples possible? In Brown, K.G., & Mayer, L. (Eds.), APA Newsletter on American Indians in Philosophy (The American Philosophical Association), 5(2), 1–12

Medina, J. (2011). The Relevance of Credibility Excess in a Proportional View of Epistemic Injustice: Differential Epistemic Authority and the Social Imaginary. Social Epistemology, 25(1), 15–35

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Grahama, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(41), 16474–16479

National Science Board (2018). Science and Engineering Indicators 2018. National Science Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2018/nsb20181/

Ortega, M. (2006). Being lovingly, knowingly ignorant: White feminism and women of color. Hypatia, 21(3), 56–74

Phillips, K. (2017). What is the real value of diversity in organizations? Questioning our assumptions. In S. Page (Ed.), The Diversity Bonus: How Great Teams Pay off in the Knowledge Economy (pp. 223–245). Princeton University Press

Page, O. (2003). Promoting Diversity in Academic Leadership. New Directions for Higher Education, 124, 79–86

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What Women and Men Should Be, Shouldn’t be, are Allowed to be, and don’t Have to Be: The Contents of Prescriptive Gender Stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(4), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Rollock, N. (2019). Still too few black female academics hold professorships. University World News: The Global Window on Higher Education. Published 11 May 2019. Retrieved from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190506150215740/

Rosser, S. (2004). The Science Glass Ceiling. Academic Women Scientist and the Struggle to Succeed. Routledge

Saul, J. (2013). Implicit Bias, Stereotype Threat, and Women in Philosophy. In F. Jenkins, & K. Hutchinson (Eds.), Women in Philosophy: What needs to change? (pp. 39–60). Oxford University Press

Schmader, T., & Johns, M. (2003). Converging evidence that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 440–452

Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group. (2017). The Burden of Invisible Work in Academia: Social Inequalities and Time Use in Five University Departments. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations Special Issue, 39, 228–245

Sonnert, G., & Holton, G. (1996). Career Patterns of Women and Men in the Sciences. American Scientist, 84(1), 63–71

sovereign, t. (2015). The Indigenous Feminist Killjoy. Blog. https://tequilasovereign.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/the-indigenous-feminist-killjoy/

Steel, D., & Bolduc, N. (2020). A Closer Look at the Business Case for Diversity: The Tangled Web of Equity and Epistemic Benefits. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 50(5), 418–443

Steel, D., Fazelpour, S., Crewe, B., & Gillette, K. (2021). Information elaboration and epistemic effects of diversity. Synthese, 198, 1287–1307

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811

Steinpreis, R., Anders, K., & Ritzke, D. (1999). The Impact of Gender on the Review of the Curricula Vitae of Job Applicants and Tenure Candidates: A National Empirical Study. Sex Roles, 41, 509–528

Stewart, A. J., & Valian, V. (2018). An Inclusive Academy: Achieving Diversity and Excellence. The MIT Press

Valian, V. (1990). Why So Slow? The Advancement of Women. The MIT Press

Wall, K. (2019). Persistence and representation of women in STEM programs. Insights on Canadian Society (Statistics Canada). Last accessed November 1, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2019001/article/00006-eng.htm

Walkington, L. (2017). How Far Have We Really Come? Black Women Faculty and Graduate Students’ Experiences in Higher Education. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 39(Special Issue), 51–65

Williams, J., Philips, K., & Hall, E. (2014). Double Jeopardy? Gender Bias Against Women of Color in Science. Tools for Change. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271529571_Double_Jeopardy_Gender_Bias_Against_Women_of_Color_in_Science

Williams, P. (1991). The Alchemy of Race and Rights. Harvard University Press

Williams, P. (2018). Silenced and objectified: black women in the US. TLS. Published 5 January 2018. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/intimate-injustice-black-girls-williams

Wylie, A., Jakobsen, J. R., & Fosado, G. (2007). Women, Work, and the Academy: Strategies for Responding to ‘Post-Civil Rights Era’ Gender Discrimination. New Feminist Solutions. http://bcrw.barnard.edu/wp-content/nfs/reports/NFS2-Women_Work_and_the_Academy.pdf

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Samantha Brennan, Shannon Dea, Peggy DesAutels, Heidi Grasswick, Daphne Gray-Grant, Tim Kenyon, Wren Lamont, Boyana Peric, Kathryn Plaisance, and Sara Weaver for rich discussions of this topic and feedback on various drafts of this paper. We are grateful for constructive feedback from the 2016 Southwestern Ontario Feminist Philosophy Workshop, the philosophy departments at Western, Wilfrid Laurier, and McMaster Universities, and three anonymous reviewers.

Funding

Janet Jones is a recipient of the Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interestsNot applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fehr, C., Jones, J.M. Culture, exploitation, and epistemic approaches to diversity. Synthese 200, 465 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03787-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03787-8