Abstract

Previous research has shown that leaders’ narcissistic rivalry is positively associated with abusive supervision. However, it remains unclear when and how leaders high in narcissistic rivalry show abusive supervision. Building on trait activation theory and the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Concept (NARC), we assumed that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry particularly show abusive supervision in reaction to follower workplace deviance due to their tendency to devaluate others. We argued that leaders’ injury initiation motives explain why leaders high in narcissistic rivalry react with abusive supervision when experiencing organization-directed or supervisor-directed deviance. However, this should not be the case for coworker-directed deviance, as leaders high in narcissistic rivalry are less likely to find such behavior violates their internal norms. We conducted two studies. In the first study, we provided participants with experimental vignettes of follower workplace deviance. In the second study, we used a mixed-methods approach and investigated leaders’ autobiographical recollections of follower workplace deviance. We found a positive direct effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry across both studies. Leaders high in narcissistic rivalry showed abusive supervision (intentions) in response to organization-directed deviance (Studies 1 and 2) or supervisor-directed deviance (Study 1), but not in response to coworker-directed deviance (Studies 1 and 2). Leaders’ injury initiation motives could in part explain this effect. We discuss findings in light of the NARC and devaluation of others and derive implications for theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Abusive supervision, which refers to leaders’ “sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (Tepper, 2000, p. 178), is a highly unethical form of leadership. We argue, similar to Schilling et al.’s (2022) considerations on inconsistent leadership, that abusive supervision is unethical from a deontological view as it violates moral principles such as treating followers in fair and respectful manners (Leventhal, 1980) and from a consequential perspective, as it seriously harms followers (e.g., Martinko et al., 2013; Schyns & Schilling, 2013). Thus, from an ethical perspective, it is very important to prevent abusive supervision by investigating its causes.

Previous research has investigated the relation between narcissism and abusive supervision (Gauglitz et al., 2022; Nevicka et al., 2018; Waldman et al., 2018; Whitman et al., 2013; Wisse & Sleebos, 2016) often treating narcissism as a unidimensional construct, which led to inconsistent findings. We, therefore, consider distinct narcissism dimensions and focus on the maladaptive dimension narcissistic rivalry (see Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Concept [NARC]; Back et al., 2013) which has been shown to consistently relate to abusive supervision (e.g., Gauglitz et al., 2022). While both narcissism dimensions serve the same central goal of building and maintaining desirable self-views, narcissists differ in the social strategies they adopt to achieve these grandiose self-views (Back et al., 2013). Narcissistic admiration describes a self-enhancing interpersonal strategy associated with striving for uniqueness, grandiose fantasies, and charming behaviors. In contrast, narcissistic rivalry describes a self-defending interpersonal strategy associated with striving for supremacy, devaluation of others, and aggressiveness. These two dimensions lead to different social outcomes and differentially impact work outcomes (e.g., Fehn & Schütz, 2020; Helfrich & Dietl, 2019). While narcissistic admiration is linked to social success, narcissistic rivalry is linked to social failure (Back et al., 2013). Accordingly, Gauglitz et al. (2022) found that only leaders’ narcissistic rivalry, but not their narcissistic admiration, is positively associated with leaders’ abusive supervision intentions and follower-reports of abusive supervision, which we hence also focus on here.

Theoretically, the aggressive tendencies of leaders high in narcissistic rivalry should not play out equally in all situations, as, according to the NARC, specific situational cues may trigger aggressive responses in such leaders (Back et al., 2013). Previous research indicates that the link between narcissism in general and aggression is dependent upon situational circumstances, such as in response to provocation (e.g., when being humiliated or receiving negative feedback; Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021; Lambe et al., 2018). We do not know under which specific situational circumstances leaders high in narcissistic rivalry are more likely show abusive supervision. Trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett & Guterman, 2000) helps understanding this mechanism as it stresses that trait-relevant situational cues trigger the expression of a given trait. Particularly, narcissistic rivalry is assumed to be triggered in situations that signal to the individual that they are not as grandiose and superior as they wished to be (Back et al., 2013). We argue here that focusing only on the leader (i.e., in terms of their narcissistic rivalry) neglects that leadership is co-created between leaders and their followers (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). While abusive supervision in itself is considered unethical and not justifiable, we argue that certain leaders will react to follower behavior with abusive supervision, thus follower behavior can trigger this type of unethical behavior in some leaders. Interestingly, May and colleagues (2014) pointed out that follower coping with destructive leadership can trigger further destructive leadership, thus leading to a downward spiral that can be difficult to break. For example, follower coping can be interpreted by the leader as aggressive and hence lead to further abuse. Here, we propose that followers can create situational cues by behaving in ways that signal insubordination, and thus triggering narcissistic rivalry and making abusive supervision more likely.

We suggest that followers who behave in deviant ways may trigger abusive supervision in leaders high in narcissistic rivalry. Deviance consists of negative behaviors in the workplace that followers enact voluntarily (Robinson & Bennett, 1995). Notably, follower deviance is quite common and has become pervasive in many organizations (e.g., Bennett & Robinson, 2000), making it likely that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry will at some point in their career be exposed to a follower who engages in deviance. The occurrence and pervasiveness of workplace deviance, together with its associated costs associated (e.g., Bennett & Robinson, 2000), highlight the importance of studying follower deviance. Previous research emphasized that it is important to differentiate between different types of deviance, as they have different predictors and because they are differentially related to important workplace criteria (e.g., Berry et al., 2007; Hershcovis et al., 2007; Mackey et al., 2021). Similarly, not all types of deviance may trigger narcissistic rivalry and evoke abusive supervision. Bennett and Robinson (2000) proposed two dimensions of deviance, that is, organizational deviance and interpersonal deviance. The latter can be further differentiated into supervisor-directed deviance and coworker-directed deviance (Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007). We assume that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry only react to deviant follower behavior against them or “their” organization (in the sense of narcissistic identification; Galvin et al., 2015), but not when it is directed against coworkers.

Furthermore, with the current research we strive to add to the question how leaders high in narcissistic rivalry show abusive supervision in response to follower deviance. This way, we take a look “inside the mind of narcissists” (Hansbrough & Jones, 2014) as narcissism is associated with specific intrapsychic cognitive processes (e.g., Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001) that potentially explain the development of abusive supervision (Hansbrough & Jones, 2014).

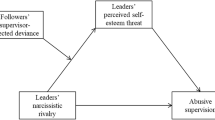

We argue that the relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision in reaction to follower deviance can be explained by motives that relate to devaluing the follower because according to the NARC, feelings of threat or insecurity can prompt the desire to devalue and harm others. Hansbrough and Jones (2014) argue that narcissists in general have negative views of their followers, which is indirectly related to abusive supervision. Indeed, Tepper (2007) differentiates between two motives for showing abusive supervision, namely, to improve followers’ performance (i.e., performance promotion motive) or to harm followers (i.e., injury initiating motives). Arguably, to instill injury in others can be assumed to be a manner of devaluing others. We argue that injury initiating motives mediate the moderating effect of different types of follower deviance on the relationship between narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision (Back et al., 2013; Hansbrough & Jones, 2014; Tepper, 2007). The theoretical model of our study is depicted in Fig. 1.

The contributions of our study are threefold. First, in line with previous research, we want to shed further light on the antecedents of abusive supervision from a leader point of view by focusing on leaders’ narcissistic rivalry (Gauglitz et al., 2022). In line with Gauglitz et al. (2022), we highlight that it is important to differentiate between different narcissism dimensions in abusive supervision research. Particularly, we want to show that narcissistic rivalry is the maladaptive narcissism dimensions with negative implications for leadership. Second, we aim to shed light on the conditions that can explain the positive relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision (intentions) by proposing a moderating effect of different types of followers’ deviance. By doing so, we advance scholars’ understanding of how abusive supervision is co-created by leaders and followers which in turn gives hints how to prevent abusive supervision from a more holistic point of view, including followers and the interaction between leader and follower. Third, we aim to illuminate the role leader motives play in the relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision and suggest that injury initiation motives mediate the moderation of follower deviance on relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision. Thus, we empirically test the theoretical proposition of the NARC, which holds that narcissistic rivalry is accompanied by devaluing thoughts about others, and investigate its application in leadership research. Thereby we can show that leaders’ narcissistic rivalry is accompanied by particular intrapsychic processes, which then translate into concrete abusive actions. Overall, our model helps to understand the leader–follower interactions that lead to abusive supervision and aims at creating of recommendations for organizations to break this vicious cycle.

Leaders’ Narcissistic Rivalry and Abusive Supervision (Intentions)

The NARC (Back et al., 2013) differentiates between two dimensions of grandiose narcissism, an assertive facet called narcissistic admiration, and an antagonistic facet called narcissistic rivalry. While the social strategies rooted in narcissistic admiration generally yield more favorable responses from others, narcissistic rivalry often results in social conflict (Back et al., 2013). For instance, individuals high in narcissistic admiration express dominant-expressive behaviors and appear as assertive persons resulting in initial popularity, whereas individuals high narcissistic rivalry show arrogant and aggressive behaviors and appear untrustworthy, resulting in a decrease in popularity over time (Leckelt et al., 2015). In addition, Back et al. (2013) showed that individuals high in narcissistic admiration are perceived as competent, sociable and attractive, whereas individuals high in narcissistic rivalry score low on empathy, gratitude, trust, and forgiveness. In sum and in line with the NARC, it seems that only individuals high in narcissistic rivalry (but not those high in narcissistic admiration) are unable to maintain close relationships and are likely to engage in aggressive behaviors. The behavioral dynamic associated with narcissistic rivalry might also explain why some leaders show abusive supervision. Given that narcissistic rivalry involves aggressive tendencies, defensive strategies, and a pronounced need to safeguard one's grandiosity (Back et al., 2013), it holds a more evident theoretical link with abusive supervision and empirical evidence supports this notion. Indeed, Gauglitz et al. (2022) found that leaders’ narcissistic rivalry (but not their narcissistic admiration) is positively associated with leaders’ abusive supervision intentions and follower-reports of abusive supervision. Hence, we assume:

Hypothesis 1:

Leaders’ narcissistic rivalry is positively associated with abusive supervision (intentions).

The Moderating Effect of Different Forms of Follower Workplace Deviance

According to the NARC, individuals high in narcissistic rivalry have a general predisposition to aggress, but will be most likely to aggress after experiencing social failure or threats to their grandiosity and superiority. This assumption is also rooted in trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett & Guterman, 2000), which holds that personality is played out in situations that are trait-relevant (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett & Guterman, 2000). It is assumed that trait-relevant situational cues release the expression of a given trait. At work, trait-relevant situational cues can be social features (behaviors of leaders or followers: Tett et al., 2021), such as specific forms of follower workplace deviance. These situational cues have the potential to indicate insubordination to the leader and consequently may provoke abusive supervision in leaders high in narcissistic rivalry. We suggest that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry will be particularly likely to aggress in response to organization- and supervisor-directed deviance in comparison to coworker-directed deviance, as these two forms of deviance indicate follower insubordination.

More specifically, one of the main tasks of a leader is to ensure that their followers respect organizational rules (Yukl & Gardner, 2019). When followers show organization-directed deviance, however, they objectively disregard organizational rules (e.g., coming in too late at work) indicating also that the leader failed in managing their followers and that they do not recognize their leaders’ authority. Consequently, these followers do not show the narcissistic leader the respect they (believes) to deserve—which might, according to the NARC, threaten their grandiose self-view and trigger narcissistic rivalry and hence aggressive responses (Back et al., 2013). Accordingly, organization-directed deviance signals insubordination and leaders are expected to intervene and ensure that followers comply with organizational rules. We assume that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry will do so by showing abusive supervision, to devaluate the follower who put them in a bad light as a leader and questioned their authority.

Supervisor-directed deviance consists of undesirable behaviors (e.g., talking rudely to the leader), which might indicate that the follower does not respect the leader and might be signaling insubordination. In addition, supervisor-directed deviance can be personally threatening to leaders high in narcissistic rivalry, as this type of disrespectful follower behavior stands in contrast to the desire of being treated with respect and admiration inherent to individuals high in narcissistic rivalry. Therefore, we assume that leaders react with abusive supervision to supervisor-directed deviance as it also includes violations of their internal norm system. Arguably, individuals high in narcissistic rivalry feel easily insulted which can lead them to retaliate (Back et al., 2013).

With regard to coworker-directed deviance, we assume that this type of behavior does not trigger abusive supervision in leaders high in narcissistic rivalry, as individuals high in narcissistic rivalry do not care for others and score low on empathy (Back et al., 2013; Leunissen et al., 2017). Furthermore, leaders high in narcissistic rivalry are characterized by a propensity to devalue others as a means to protect their grandiose self-views (Back et al., 2013). When followers show coworker-directed deviance, they essentially devalue their colleagues, which may resonate with the narcissistic leaders’ tendency to derogate and belittle. These leaders might see such behaviors as a reflection of their own inclination to devalue others. In this context, coworker-directed deviance does not necessarily violate their internal norms of appropriate behavior towards third parties. Taken together, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2:

The positive relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision is moderated by follower workplace deviance, such that it is strongest when followers show organization-directed deviance and supervisor-directed deviance compared to coworker-directed deviance.

The Mediating Role of Injury Initiation Motives

Differentiating performance promotion motives and injury initiation motives (Tepper, 2007) links to the two social strategies assumed by the NARC. Specifically, we argue that striving for supremacy can be expressed in the context of abusive supervision as performance promoting motive and devaluating others as injury initiating motive. While previous research focused on the first aspect (striving for supremacy) and investigated ego threat (Gauglitz et al., 2022), we argue that the second aspect—devaluating others—can equally lead to abusive supervision. Hansbrough and Jones (2014) suggested that narcissistic leaders hold negative views of others and this likely means that they also interpret follower behavior in a way to confirm their negative views (which is in line with Back et al., 2013, arguing that devaluating others is a cognitive process). Hence, they are likely to interpret follower deviance negatively as insubordinations which triggers devaluation and justifies the use of abusive supervision to leaders high in narcissistic rivalry. That is, their motive for showing abusive supervision is injury motivation. We assume that follower organization-directed and supervisor-directed deviance trigger injury initiation motives in leaders high in narcissistic rivalry.

Ultimately, according to the NARC, devaluing thoughts (i.e., injury initiation motives) lead to aggressive behaviors (i.e., abusive supervision). Accordingly, we suggest that injury initiation motives experienced by leaders high in narcissistic rivalry in response to organization-directed and supervisor-directed deviance will translate into abusive supervision. In sum, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3:

There is an indirect effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision (intentions) via injury initiation motives when followers show organization-directed deviance or supervisor-directed deviance.

Study Overview

To test our hypotheses, we adopted a comprehensive multi-method approach, drawing on both experimental and field-based designs across two studies. In Study 1, we used experimental vignettes, a controlled methodology that offers several distinct advantages: First, this design allowed us to manipulate specific variables in a systematic manner (i.e., types of follower deviance) and thereby enabled us to draw conclusions about the causal ordering of our focal variables (Antonakis et al., 2010). Second, the experimental nature of Study 1 in combination with a random assignment of participants to conditions mitigates common concerns related to demographic biases (making it redundant to control for demographics or other participant characteristics) and attenuates the threats of common method variance (Cooper et al., 2020). In Study 2, we sought external validity by examining leaders in real-world settings. Here, we collected leaders’ autobiographical memories of follower workplace deviance and assessed whether they subsequently showed abusive supervision. This field-based study grounded our findings in actual organizational settings and offered a more holistic picture. While we acknowledge the susceptibility of Study 2 to common method variance, the replication of the findings in the experimental context of Study 1 should (at least in parts) relieve these concerns, underscoring the credibility of our results. Also, in order to reduce the risk of common method variance, we used scales with different scale properties in (e.g., in terms of number of scale points and anchor labels) and aimed at reducing social desirability by ensuring anonymity to our study participants (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Study 1

Method

Sample and Procedure

Study 1 was an online experimental vignette study in which we manipulated follower workplace deviance. Participants were recruited via snowball procedure in Germany. Eligible participants were employed and had at least 6 months of work experience. Overall, 155 participants took part in the experimental vignette study. We deleted three participants who stated that they did not find the described vignettes credible at all or who could not place themselves in the situation described in the experimental vignette. Our final sample consisted of 152 participants (coworker-directed deviance condition: N = 52, organization-directed deviance condition: N = 52, and supervisor-directed deviance condition: N = 48). We employed a between-subjects design where conditions were randomly assigned. Participants were on average 37.08 years old (SD = 14.54) and 59.9% of participants were women. On average, participants worked 37.35 h per week (SD = 9.24) and 63.8% of participants did not hold a leadership position.

To reduce common method variance, we separated measurements in time (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Therefore, data were collected with a time lag of two days. At the first measurement point, we assessed our independent (narcissistic rivalry) and our control variable (narcissistic admiration) as well as sociodemographic information in order to describe the sample. At the second measurement point, participants read one of three experimental vignettes and subsequently indicated their injury initiation motives as well as their abusive supervision intentions.

Measures

We measured leaders’ narcissistic rivalry with nine items of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ; Back et al., 2013). A sample item is “Most people won’t achieve anything” (α = 0.80). In line with previous research (Gauglitz et al., 2022), we controlled for leaders’ narcissistic admiration using the corresponding nine items of the NARQ (Back et al., 2013). A sample item reads “Being a very special person gives me a lot of strength” (α = 0.82). Participants indicated their agreement to the items on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not agree at all) to 6 (agree completely).

Injury initiation motives were measured with an adapted version of Liu and colleagues’ (2012) injury initiation and performance promotion motives scales (five items). Independent language experts translated and back translated the items. We asked participants regarding their injury initiation motives towards the employee who showed workplace deviance in the described experimental vignette. A sample items was “I desire to cause injury on my subordinate” (α = 0.83). Participants rated their agreement to these items on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not agree at all) to 7 (agree completely).

Abusive supervision was measured using the 15 items of the German version of Tepper’s (2000) abusive supervision scale (Schilling & May, 2015). We asked participants how likely it would be that they showed abusive supervision towards the employee who showed workplace deviance in the described experimental vignette. A sample item was “I would ridicule my subordinate” (α = 0.80). Participants indicated their agreement with these items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely).

Development and Content of Experimental Vignettes

We developed three experimental vignettes, one for each condition (i.e., supervisor-directed, organization-directed, and coworker-directed deviance). Each experimental vignette included an introduction followed by the specific episode of follower workplace deviance (e.g., supervisor-directed, organization-directed, and coworker-directed deviance). First, all participants were instructed to put themselves in the role of a leader and to read the scenarios carefully. Next, all participants received the same background information to enable them to embed their responses contextually (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014). Participants were told that they worked for a software company and received information about their job duties, including delegating work to their followers and monitoring their work progress. Then, a paragraph with the deviance scenario followed. Participants were told that they observed their follower showing workplace deviance. We based the behaviors and the wording of our experimental vignettes on existing scales and experimental vignettes that capture different forms of workplace deviance (Bennett & Robinson, 2000; Lapierre et al., 2009; Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007). For instance, in the organization-directed deviance condition, the follower was described as someone who came in late without permission, took longer brakes than permitted, and intentionally worked slower than he/she could have worked. In the supervisor-directed deviance condition, the follower was described as someone who behaved disrespectful towards the leader, publicly embarrassed him/her, and made fun of him/her. The follower-directed deviance condition consisted of the same deviant behaviors except that they were directed at a coworker. The appendix contains the full experimental vignettes.

Manipulation Checks

After reading the experimental vignettes, participants were asked how deviant they found the follower’s behavior on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not deviant at all—5 = very deviant). In all three conditions, participants rated the described follower’s behavior as deviant (organization-directed deviance: M = 3.65, SD = 0.86; supervisor-directed deviance: M = 4.21, SD = 0.90; coworker-directed deviance: M = 4.52, SD = 0.73).

Results

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, correlations and internal consistency estimates for the study variables and Table 2 gives an overview of the means of our variables in each deviance condition. To test Hypothesis 1, we conducted a linear regression analysis with leaders’ narcissistic rivalry as predictor and leaders’ narcissistic admiration as covariate (see Table 3). Leaders’ narcissistic rivalry was significantly and positively associated with abusive supervision intentions (β = 0.52, p < 0.001), lending support for Hypothesis 1. This model explained 22% of variance in abusive supervision intention ratings (p < 0.001).

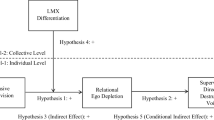

To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, we conducted a conditional process analysis using the process macro by Hayes (2018). Specifically, we used model 8 of the process macro and included leaders’ narcissistic rivalry as predictor, follower deviance as moderator, injury initiation motives as mediator, leaders’ abusive supervision intentions as outcome, and leaders’ narcissistic admiration as covariate. As our moderator (follower deviance) was multicategorical (with k = 3 conditions, i.e., supervisor-directed, organization-directed, and coworker-directed deviance), we followed West et al. (1996) and chose a dummy coding system to test the proposed interactions.Footnote 1

Results revealed that the effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision did not differ between the organization-directed deviance (B = 0.24, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.10, 0.38]), supervisor-directed deviance (B = 0.30, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI 0.15, 0.46]), and coworker-directed deviance (B = 0.07, SE = 0.06, p = n.s., 95% CI [-0.06, 0.19]) conditions, as indicated by overlapping confidence intervals (see Table 4). However, the effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision was only significant in the organization-directed and supervisor-directed deviance condition, which lends partial support for Hypothesis 2.

Moreover, we found significant indirect effects via injury initiation motives in the organization-directed (B = 0.12, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.04, 0.25]) and supervisor-directed (B = 0.22, SE = 0.11, 95% CI [0.06, 0.47]) deviance condition (see Table 5), supporting Hypothesis 3 (see also Fig. 2). There was also an indirect effect via injury initiation motives in the coworker-directed deviance condition (B = 0.09, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.02, 0.25]). In sum, we find a consistent pattern in that injury initiation motives can explain the positive association between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision intentions.

Study 2

Method

Sample and Procedure

Next, we conducted an online study focusing on leaders’ interactions with followers to test our hypotheses with a different methodological approach and to enhance external validity of our findings. Study participants were recruited via snowball sampling in Germany. We chose a mixed-method approach and included quantitative as well as qualitative questions. In the qualitative part, participants recollected an episode in which one of their followers behaved in a deviant manner. Overall, 166 participants completed the questionnaire. We deleted participants who did not pass quality checks (n = 9) or who did not describe a situation (n = 10) leading to a sample of 147. After screening participants’ descriptions of situations, we deleted participants who did not describe a relevant situation (n = 6, see also data analysis). The final sample consisted of 141 leaders (68.1% male) who were on average 46.7 years old (SD = 11.44), had an average leadership experience of 13.6 years (SD = 9.43), held a middle management position in 44.7% of the cases, and worked on average 45.5 h per week (SD = 9.02).

Measures

We measured leaders’ narcissistic rivalry (α = 0.82) and admiration (α = 0.84) with the same items as in Study 1.

To assess follower workplace deviance, we asked participants to recall an episode of follower workplace deviance. We did not restrict participants in terms of a time frame but rather left it up to them to remember an episode. This way we aimed to capture an episode that was particularly salient to them. To do so, we first provided participants with Robinson and Bennett’s (1995) definition of workplace deviance and then instructed them to remember a situation in which one of their followers displayed workplace deviance. Participants were asked to answer three questions (“What happened exactly?”, “What exactly did your subordinate do or say?”, and “In how far were you involved in the situation?”) and to write their answers into a free text field.

Afterwards, we assessed leaders’ injury initiation motives with the same items as in Study 1, but we slightly adapted instructions. We asked participants to what extent they had experienced injury initiation motives in the described situation (“Which motives did you experience in the situation you just described?”). Specifically, we asked participants for their response to a specific event—an episode of follower workplace deviance, indicating their behavioral reactions rather than general behavior tendencies. That is, in the described situation, participants might have shown some but not all of the behaviors indicated in the scales, making a reliability assessment less valid for our purposes. A sample items was “I desired to cause injury on my subordinate” (α = 0.48).

We measured abusive supervision with the same scale as in Study 1 and asked participants to what extent they had shown abusive supervisory behaviors towards their subordinate in response to the described situation of workplace deviance. Therefore, participants’ responses reflect specific behavior indicators and not general behavior tendencies. A sample item was “I ridiculed my subordinate” (α = 0.67). Participants indicated their agreement with these items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not agree at all) to 5 (agree completely).

We conducted two Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) in order to examine the discriminant validity of our measures. In the first CFA, the items of all measures loaded on one global factor, and in the second CFA, all items loaded on their respective latent construct (resulting in 4 factors: narcissistic admiration, narcissistic rivalry, injury initiation motives, and abusive supervision). Results revealed that the 4-factor solution (χ2 = 1041.78, df = 647, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.75, SRMR = 0.09) yielded a better fit than the 1-factor solution (χ2 = 1694.06, df = 665, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.11; CFI = 0.35, SRMR = 0.11). This indicates that the items in the data are better represented by four distinct constructs rather than a single overarching construct, providing support for the discriminant validity of the four underlying latent constructs.

Data Analysis

We first analyzed participants’ descriptions of follower workplace deviance (n = 147). In four cases, no relevant episode of follower workplace deviance was described and thus we excluded these four cases from our data set. Next, two researchers analyzed the remaining 143 cases and examined at whom the described follower workplace deviance was directed. More specifically, we predefined categories of follower workplace deviance that is directed at the organization (organization-directed deviance), the supervisor (supervisor-directed deviance), or other individuals in the organization (coworker-directed deviance). The two researchers independently coded the episodes of workplace deviance using these three categories. In 104 cases, consensus was reached between the two researchers. In the remaining 39 cases, a third researcher independently coded the episodes. Afterwards, the researchers discussed the examples and solved the coding problems. In two cases, no consensus was reached and therefore two cases were deleted from our data set. Of the remaining 141 experiences, 21 were coded as coworker-directed deviance (examples included for instance rude comments toward coworkers, or talking badly about coworkers behind their back), 59 were coded as supervisor-directed deviance (examples included being rude toward the leader or not following the leaders’ instructions), and 61 were coded as organization-directed deviance (examples included coming in late, taking longer brakes than allowed, intentionally working slowly, or theft). Overall, respondents reported diverse incidents that varied in severity.

Results

Means, standard deviations, correlations and internal consistency estimates are depicted in Table 1 and 2 gives an overview of the means of our variables in each condition. To test Hypothesis 1, we conducted a linear regression analysis with leaders’ narcissistic rivalry as predictor, abusive supervision as dependent variable, and leaders’ narcissistic admiration as control variable (see Table 3). As expected, leaders’ narcissistic rivalry was significantly and positively associated with abusive supervision (β = 0.19, p < 0.05) supporting Hypothesis 1. This model accounted for 7% of variance in abusive supervision ratings (p < 0.05).

To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, we used model 8 of the process macro (Hayes, 2018) as in Study 2. We included leaders’ narcissistic rivalry as predictor, follower deviance as moderator (again using the dummy coding option as described in Study 1), leaders’ injury initiation motives as mediator, leaders’ abusive supervision as outcome, and leaders’ narcissistic admiration as control variable. Results revealed that the effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision did not differ between the organization-directed deviance (B = 0.15, SE = 0.07, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.02, 0.29]), supervisor-directed (B = 0.04, SE = 0.05, p = n.s., 95% CI [-0.06, 0.14]), and coworker-directed deviance (B = -0.08, SE = 0.16, p = n.s., 95% CI [-0.40, 0.24]) conditions, as indicated by overlapping confidence intervals (see Table 4). However, the effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision was only significant in the organization-directed deviance condition, which lends partial support for Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, there was an indirect effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision via injury initiation motives when followers showed organization-directed deviance (B = 0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.16]), but not in the supervisor-directed (B = -0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [-0.06, 0.04]) and coworker-directed (B = -0.01, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [-0.07, 0.07]) deviance conditions (see Table 5, and Fig. 2). These results lend partial support for Hypothesis 3.

Post-Hoc Analyses

Results with Leaders’ Narcissistic Admiration as Predictor

Across both studies, as a robustness check, we additionally ran our analyses with leaders’ narcissistic admiration as a predictor, follower deviance as moderator (which was dummy coded as in Studies 1 and 2), injury initiation motives as mediator, leaders’ abusive supervision (intentions) as outcome, and leaders’ narcissistic rivalry as covariate. We used Model 8 of the process macro by Hayes (2018).

In Study 1, the effect of leaders’ narcissistic admiration on abusive supervision intentions was not significant in the organization-directed deviance condition (B = − 0.03, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.15, 0.09]) and the supervisor-directed deviance condition (B = − 0.00, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [− 0.14, 0.14]), but it was significant in the coworker-directed deviance condition (B = − 0.13, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.22, − 0.03]). Moreover, there were no significant indirect effects via injury initiation motives in the organization-directed (B = − 0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.06, 0.03]), supervisor-directed (B = − 0.02, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.11, 0.07]), and coworker-directed (B = − 0.03, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.11, 0.03]) deviance conditions.

In Study 2, the effect of leaders’ narcissistic admiration on abusive supervision was neither significant in the organization-directed deviance condition (B = 0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.16]), nor in the supervisor-directed deviance condition (B = 0.03, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.06, 0.11]), nor in the coworker-directed deviance condition (B = 0.01, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [− 0.12, 0.14]). Additionally, there were no significant indirect effects via injury initiation motives in the organization-directed (B = 0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.04]), supervisor-directed (B = 0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.05, 0.05]), and coworker-directed (B = 0.00, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.02]) deviance conditions.

Results with Performance Promotion Motives as Mediator

We conducted another robustness check, testing performance promotion motives as an alternative mediator. We again used model 8 of the process macro by Hayes (2018). We included leaders’ narcissistic rivalry as predictor, follower deviance as moderator, performance promotion motives as mediator, leaders’ abusive supervision as outcome, and leaders’ narcissistic admiration as covariate. In Study 1, there were no significant indirect effects via performance promotion motives neither in the organization-directed (B = − 0.00, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.03, 0.02]), nor in the supervisor-directed (B = 0.00, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.03]), or coworker-directed (B = 0.00, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.03]) deviance conditions. In Study 2, there were no significant indirect effects via performance promotion motives in the organization-directed (B = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.07]) or coworker-directed (B = − 0.02, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.10, 0.10]) deviance conditions. However, there was a very small indirect effect in the supervisor-directed deviance condition (B = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.00, 0.07]).

Discussion

Within two studies, we investigated the relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision (intentions). Building on the NARC (Back et al., 2013), we assumed that leaders’ narcissistic rivalry—the antagonistic facet of narcissism—is associated with abusive supervision. Across two studies, we consistently found that leaders’ narcissistic rivalry was positively associated with abusive supervision (intentions; for a similar result see Gauglitz et al., 2022). Furthermore, building on trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett & Guterman, 2000), we examined the role of different types of follower workplace deviance as trait-relevant situational cues that may trigger narcissistic rivalry in these leaders and make abusive supervision more likely. Leaders high in narcissistic rivalry showed abusive supervision (intentions) when deviance was directed at the organization (Studies 1 and 2) or at themselves (Study 1), but not when it was directed at coworkers (Studies 1 and 2). Finally, in line with previous literature (Hansbrough & Jones, 2014; Tepper, 2007), we focused on leaders’ injury initiation motives as potential explanation of abusive supervision. We consistently found that leaders’ injury initiation motives explained why leaders high in narcissistic rivalry displayed abusive supervision (intentions) in response to followers’ organization-directed deviance (Studies 1 and 2), and in part in response to followers’ supervisor- and coworker-directed deviance (Study 1). These findings contribute to the literature in the following ways.

Theoretical Implications

We were able to replicate previous findings regarding a positive association between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision (intentions; Gauglitz et al., 2022). Interestingly, when asking leaders high in narcissistic rivalry about their own behavior (Study 2), they were ready to admit that they had shown abusive supervision in the past, even though it might reflect negatively on them. This is consistent with past research showing that narcissistic individuals are aware of and admit to narcissistic behaviors and at the same time realize it is socially undesirable (e.g., Carlson, 2013). It is, however, important to note that both narcissism and abusive supervision are low-based rate phenomena (e.g., Fischer et al., 2021; Gauglitz et al., 2022) and we found, accordingly, low mean values on both variables.

Furthermore, while previous research has shown that the relation between narcissism and aggression is stronger in some situations (e.g., in response to provocation) than in others (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021; Lambe et al., 2018), it remained open under which circumstances leaders high in narcissistic rivalry would be more or less likely to show abusive supervision. In our study, we examined whether follower behaviors (i.e., workplace deviance) could trigger narcissistic rivalry and thus make abusive supervision more likely. By doing so, we acknowledge that leadership is co-created between leaders and their followers (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). We only found partial support for our hypothesis that the positive relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision is strongest when followers show organization-directed deviance and supervisor-directed compared to coworker-directed deviance. While the effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision was significant in the organization-directed deviance condition in both studies, it was only significant in the supervisor-directed deviance condition in Study 1. Yet, in the coworker-directed deviance condition, the positive association between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision was insignificant in both studies as expected. Our findings are also in line with the broader literature on workplace deviance, which has shown that it is important to differentiate between different forms of deviance due to their distinct relations with outcomes (Berry et al., 2007; Mackey et al., 2021).

We conclude here that organization-directed deviance is a social cue at work which signals follower insubordination and evokes abusive supervision (intentions) in leaders high in narcissistic rivalry. Followers who display organization-directed deviance do not stick to organizational rules, which implies that the leader is not capable to ensure that their followers respect organizational rules. It also signals that they do not accept the leader as a relevant authority and that they do not pay the leader the respect he/she (believes to) deserve. This lack of respect might, according to the NARC, threaten the grandiose self-view of the narcissistic leader and trigger aggressive responses. We proposed and found that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry would react with abusive supervision in such a case in order to put down the source who put them in a bad light as a leader and who questioned their authority. When followers show organization-directed deviance, it is expected that the leader intervenes and corrects the norm-violating behavior of this follower. Thus, these leaders even have a justification for their behavior as they have to restore order.

Interestingly, we found mixed results with regard to supervisor-directed deviance. Leaders high in narcissistic rivalry tended to show abusive supervision in Study 1, but not in Study 2. We wonder if these differences are a result of the different methods we used in the studies. In Study 1, participants in the supervisor-directed deviance condition reacted with abusive supervision intentions to the described episode of supervisor-directed deviance (e.g., being publicly embarrassed or being made fun of). Such behaviors can be perceived as insubordination and might trigger narcissistic rivalry, which then make aggressive responses in the workplace, such as abusive supervision, more likely. Contrary to that, in Study 2, we asked leaders to remember a situation in which one of their followers behaved in a deviant way. While some leaders remembered situations of supervisor-directed deviance, it could be that leaders high in rivalry did not recall situations that were highly threatening to their leader authority. That means that mnemic neglect might have occurred which describes that individuals poorly recall self-threatening information (Sedikides and Green, 2000, 2009). Mnemic neglect has a self-protective function (Pinter et al., 2011) and leaders high in rivalry strive to protect their grandiose self-views (Back et al., 2013). Accordingly, these leaders might have recalled episodes of supervisor-directed deviance that were not highly threatening to their grandiose self-views. Alternatively, they might not even have reported those events and focused on other types of deviances that are less self-threatening.Footnote 2 Consequently, mnemic neglect could explain why leaders’ narcissistic rivalry was unrelated to reports of abusive supervision in response to supervisor-directed deviance in Study 2. At the same time, the mere fact of asking them to remember a supervisory situation might have triggered narcissistic leaders’ concern about their grandiose self-views and caused them to remember events that were more flattering for their self-views. Further research is needed to examine if supervisor-directed deviance is subject the mnemic neglect, particularly for individuals high in narcissistic rivalry.

Consistently, and across both studies, we found that the positive association between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision (intentions) was insignificant in the coworker-directed deviance condition. It seems that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry care less when their followers show coworker-directed deviance. This might be due to their lack of empathy and care for others (Back et al., 2013; Leunissen et al., 2017). Speaking in terms of trait activation theory and the NARC, it seems that coworker-directed deviance is not a trait-relevant situational cue and does not threaten the leaders’ grandiose self-views as we expected.

Third, our findings offer insights into the intrapsychic processes of narcissistic leaders who are exposed to follower workplace deviance. Previous research lacks a thorough understanding of the motives that drive abusive supervision (Spain et al. 2014). Our research addresses this research gap by combining the assumptions by Tepper (2007), who argued that leaders might show abusive supervision because they want to harm their followers, and Hansbrough and Jones (2014), who suggested that leaders’ negative views of their followers could explain why they show abusive supervision. Specifically, we assumed that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry would develop a motive to harm their followers in response to organization-directed and supervisor-directed deviance, because such follower behavior signals insubordination and may fuel the wish to put the follower down. According to Hansbrough and Jones (2014), insubordination in turn triggers abusive supervision. In line with this assumption, we found an indirect effect of leaders’ narcissistic rivalry on abusive supervision (intentions) via injury initiation motives when followers showed organization-directed deviance (both studies) and in part when followers displayed supervisor-directed deviance (Study 1). We conclude here that abusive supervision is a goal-directed behavior that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry use to threaten a follower who broke organizational rules and who did not pay them the respect they deserved. This finding is in line with the NARC, according to which devaluation of others is a social strategy individuals high in narcissistic rivalry use, which makes aggressive reactions (i.e., abusive supervision) more likely. With our study, we contribute to our understanding of the mechanisms that lead to abusive supervision in a very important way. Theoretically, injury initiation motives might explain why leaders show abusive supervision in general (Tepper, 2007). However, in the case of leaders high in narcissistic rivalry, they show abusive supervision because they want to harm their followers who actually misbehaved (particularly by showing organization-directed deviance) and signaled insubordination (Hansbrough & Jones, 2014). This stresses that narcissistic rivalry is the antagonistic side of narcissism that goes along with devaluing thoughts about others and is triggered by situational cues (Back et al., 2013).

Practical Implications

Our study offers several practical implications. As leaders’ narcissistic rivalry is positively associated with abusive supervision (intentions), organizations may want to take interventions that focus on such leaders. Schyns et al. (2022) point out several HR practices that can be taken to prevent the behavioral expression of leader narcissism, such as in recruitment and promotion career development and training, performance appraisal and feedback systems, complaint systems, and disciplinary actions. Organizations could offer trainings to leaders high in narcissistic rivalry to lead supportively (Gonzalez-Morales et al., 2018) and indeed research has shown that particularly narcissists can be motivated to improve in developmental settings (Harms et al., 2011). Leaders high in narcissistic rivalry should also receive psychoeducation. For instance, they should be made aware of the negative consequences of abusive supervision (e.g., stress and unproductivity; Schyns & Schilling, 2013) and that unhealthy and unproductive followers might reflect badly on them.

While our results also show that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry react negatively to some forms of follower deviance, it is important to emphasize that abusive supervision is never a suitable or justifiable response. Instead, it is harmful and unethical, independently of any preceding factors. Our findings thus serve as an alert for organizations regarding potential triggers that might exacerbate abusive supervision tendencies in leaders high in narcissistic rivalry. Organizations should therefore be proactive in addressing follower and leader dynamics that could give rise to unhealthy interactions. For example, organizations can create clear rules of acceptable conduct, such as charters relating to defining and encouraging respectful reciprocal interaction. Clear rules in terms of acceptable organizational behavior could be helpful, particularly when it is clear how such behavior is punished. This could, for example, be directly undertaken by HR, thus avoiding that the relationship between leader and follower further deteriorates. It is essential that organizations recognize the importance of fostering a supportive environment in which both leaders and followers are equipped with the skills and knowledge to interact respectfully with each other.

Furthermore, as our research shows that injury initiation motives can explain why leaders high in narcissistic rivalry show abusive supervision in response to workplace deviance, interventions may also focus on reducing such negative thoughts in leaders. Of course, such negative thoughts could be the result of a longer-term interaction characterized by mutual negative behaviors. In such cases, team building aimed at improving relationships could be helpful to break the cycle of deviance and abusive supervision.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

As other studies using experimental designs, in Study 1, we could ensure that follower workplace deviance precedes our mediator (i.e., leaders’ injury initiation motives) and dependent variable (i.e., abusive supervision intentions). However, we have to be cautious about the causal ordering of our mediator and dependent variables (Antonakis et al., 2010; Hamilton & Nickerson, 2003). Future research could therefore implement experimental-causal-chain designs in order to establish a causal ordering (Spencer et al. 2005). Similar to other experimental studies, in Study 1 we chose a between-subjects design to keep participants’ workload low. Our approach did not allow us to make comparisons within the same person, that is, how different forms of follower workplace deviance effect abusive supervision in the same narcissistic individual. To overcome this restriction, future studies could implement within-person designs (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014). Similar to other studies that have limited capacities, we only used a one-item manipulation check in Study 1. In future research it would be recommendable to conduct a more elaborated manipulation check to increase the confidence in the validity of our manipulations.

Study designs as ours do not allow examining reverse causality or dynamic processes. Existing research shows that follower can react to abusive supervision with deviant follower behavior as a form of retaliation (Simon et al., 2015). This likely leads to further abusive supervision in reaction to the deviant follower behavior. This negative dynamic process of action and reaction is likely to be particularly problematic when the leader is high in narcissistic rivalry, such that they show stronger abusive supervision triggering more negative responses from followers. At the same time, this cycle might be less easy to break when leaders are high in narcissistic rivalry as narcissists are not very open to feedback (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021; Lambe et al., 2018).

A limitation that is rather common in the field of narcissism and abusive supervision research pertains to the low means and standard deviations of our study variables. While our values are in line with previous research (at least regarding abusive supervision and narcissistic rivalry; e.g., Fischer et al., 2021; Gauglitz et al., 2022), we must also acknowledge that our observations are derived from a context with low manifestation of narcissistic rivalry, injury initiation motives, and abusive supervision. This poses questions regarding the generalizability of our findings. While our studies show that even low levels of narcissistic rivalry and injury initiation motives can have detrimental effects, future research should aim to replicate and extend our findings in diverse contexts and samples with broader variance to observe how more extreme levels of narcissistic rivalry and injury initiation motives relate to abusive supervision. For example, some industries might be more attractive to leaders high in narcissistic rivalry than others. A recent study (Schyns et al., 2023) looked at the context of education and found that vulnerable narcissistic leadership is linked to lower follower well-being during the Covid pandemic. Education might be particularly interesting for leaders high in narcissistic rivalry as it comes with a high status in society while at the same time, most of the interactions between colleagues are not in the public eye.

In terms of the more specific limitations of our study, in Study 2 we collected leaders’ autobiographical memories of follower workplace deviance. However, this approach does not provide information about 1) the severity of incidents or 2) the relative importance of follower workplace deviance as an antecedent of abusive supervision in comparison to other causes. A fruitful approach for future research would therefore be to let leaders recapture an episode of abusive supervision and then 1) examine the severity of incidents (e.g., did these incidents primarily involve minor issues, such as extending break durations beyond the permitted limit, or did they also encompass more serious matters?) and 2) ask them to name the reasons why they showed abusive supervisory behavior. This would show us 1) whether severity of different forms of workplace deviance makes a difference and 2) how often follower workplace deviance is named as a cause of abusive supervision relative to other causes. This would broaden our understanding of leaders’ self-reported reasons for abusive supervision and would enable us to examine if follower workplace deviance is a frequent cause of abusive supervision.

In the instruction of Study 2, we asked participants to remember an episode of follower workplace deviance but did not restrict it to a certain time period as doing so would have limited the availability of possible episodes. Hence, it could be that some leaders described an episode that happened just recently while others recaptured an episode that happened a longer time ago. Accordingly, participants might have found it more difficult to remember their reactions to some autobiographical episodes of follower workplace. While it is a strength of our design that participants described their own experiences, making the responses less hypothetical, it also a limitation, as some events might have happened longer ago.

We focused on injury initiation motives for abusive supervision based on Tepper’s (2007) suggestion, and on Hansbrough and Jones’ (2014) assumption that narcissistic leaders might interpret follower behavior in negative ways and as insubordination which might then trigger abusive supervision. However, other motives might also be relevant for leaders high in narcissistic rivalry. We did not find that performance promoting motives are a consistent mediator but, based on the NARC, one question is if leaders react to other follower behaviors with the motive to signal their supremacy to others. Furthermore, it has been assumed that status-protection is an important motive that guides the behavior of individuals high in narcissistic rivalry such that they behave aggressively when their status is undermined (Grapsas et al., 2019). Using the design of Study 2, future research could explicitly manipulate the tendency to devaluate others, striving for supremacy, and status-protection by asking participants to report situations where they felt that followers were not acting in line with their expectation. From these situations, future research could then construct vignettes to further investigate the differing experiences and how they relate to abusive supervision.

We only focused on leaders high in narcissistic rivalry and their motives but future research could also investigate under which conditions leaders high in narcissistic admiration show abusive supervision. While our robustness check showed little support for the relationship between narcissistic admiration and abusive supervision, other moderators might be relevant. It has been argued that narcissistic admiration is the “default mode” as long as individuals receive the admiration they think they deserve (Back, 2018). When they perceive a lack of admiration, however, narcissistic rivalry and the associated behavioral dynamics are triggered, so that narcissistic admiration might affect abusive supervision via processes similar to narcissistic rivalry under the condition that those leaders experience a lack of admiration. Research has shown that narcissists devalue the source of feedback (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021; Lambe et al., 2018). It would be interesting to examine if leaders high in narcissistic admiration consider negative feedback at work as a lack of admiration which then triggers narcissistic rivalry and initiates the antagonistic processes associated with narcissistic rivalry. There is also a possibility that narcissistic admiration is linked to abusive supervision as they might use performance enhancing motives to increase their status via increased follower performance. That is, they feel that their abusive supervision is justified to motivate followers into higher performance which then should reflect well on their own status.

Our studies showed that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry show abusive supervision in reaction to follower deviance. This bears the question if under conditions where followers show no counterproductive work behavior or maybe even organizational citizenship behavior, leaders high in narcissistic rivalry would function well as leaders. That is, if under different conditions our results that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry show abusive supervision would still hold. We suggest that future research addresses this question and examines also positive follower behavior and how it affects abusive supervision of leaders high in narcissistic rivalry.

Conclusion

With our research we added to the knowledge regarding the link between leader narcissism and abusive supervision (intentions) using an experimental vignette study and a new methodology (leaders’ autobiographical recollections). By doing so, we lend further support for the assumption that narcissistic rivalry is the antagonistic narcissism dimension associated with negative social outcomes. Furthermore, we were able to show that leaders high in narcissistic rivalry show abusive supervision only in reaction to some forms of workplace deviance. Finally, we offer an explanation why leaders high in narcissistic rivalry show abusive supervision (intentions) in reaction to followers’ organization-directed deviance. It seems that these leaders show abusive supervision (intentions) with the motive to injure their followers.

Notes

The process macro provides the option to indicate whether the moderator variable is multicategorical—and we chose this option using indicator coding. The process macro then automatically represents the moderator variable by k—1 variables coding group membership (Hayes and Montoya 2017). Thus, in our case, our moderator variable (follower deviance) was represented with 3−1 = 2 dummy variables (D1 and D2). In the coworker-directed deviance condition, D1 = D2 = 0, in the supervisor-directed deviance condition D1 = 1 and D2 = 0, and in the organization-directed deviance condition, D1 = 0 and D2 = 1. We ran one regression analysis which includes two interactions terms (D1 x Narcissistic Rivalry and D2 x Narcissistic Rivalry).

In response to a reviewer comment, we additionally tested the following: First, whether or not the conditions differed in term of valence or counterproductivity. We found no mean differences in valence or counterproductivity between groups. Second, we tested the correlation between narcissistic rivalry and valence and counterproductivity in each group. None of the correlations was significant. This contradicts our assumption. However, we did not directly assess how threatening the situations were.

References

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114547952

Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1086–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010

Back, M. D. (2018). The Narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept. In A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), Handbook of trait Narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 57–67). Springer International Publishing.

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C. P., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 1013–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034431

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.349

Berry, C. M., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.410

Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219

Carlson, E. N. (2013). Honestly arrogant or simply misunderstood? Narcissists’ awareness of their narcissism. Self and Identity, 12(3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2012.659427

Cooper, B., Eva, N., Fazlelahi, F. Z., Newman, A., Lee, A., & Obschonka, M. (2020). Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103472

Fehn, T., & Schütz, A. (2020). What you get is what you see: Other-rated but not self-rated leaders’ narcissistic rivalry affects followers negatively. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04604-3

Fischer, T., Tian, A. W., Lee, A., & Hughes, D. J. (2021). Abusive supervision: A systematic review and fundamental rethink. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(6), 101540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101540

Galvin, B. M., Lange, D., & Ashforth, B. E. (2015). Narcissistic organizational identification: Seeing oneself as central to the organization’s identity. Academy of Management Review, 40(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0103

Gauglitz, I. K., Schyns, B., Fehn, T., & Schütz, A. (2022). The dark side of leader narcissism: The relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05146-6

Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., Kernan, M. C., Becker, T. E., & Eisenberger, R. (2018). Defeating abusive supervision: Training supervisors to support subordinates. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000061

Grapsas, S., Brummelman, E., Back, M. D., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2019). The “why” and “how” of narcissism: A process model of narcissistic status pursuit. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 150–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619873350

Hamilton, B. H., & Nickerson, J. A. (2003). Correcting for endogeneity in strategic management research. Strategic Organization, 1(1), 51–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127003001001218

Hansbrough, T. K., & Jones, G. E. (2014). Inside the minds of narcissists: How narcissistic leaders’ cognitive processes contribute to abusive supervision. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 222(4), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000188

Harms, P. D., Spain, S. M., & Hannah, S. T. (2011). Leader development and the dark side of personality. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(3), 495–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.007

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., & Montoya, A. K. (2017). A tutorial on testing, visualizing, and probing an interaction involving a multicategorical variable in linear regression analysis. Communication Methods and Measures, 11(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1271116

Helfrich, H., & Dietl, E. (2019). Is employee narcissism always toxic?—The role of narcissistic admiration, rivalry and leaders’ implicit followership theories for employee voice. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1575365

Hershcovis, M. S., Turner, N., Barling, J., Arnold, K. A., Dupré, K. E., Inness, M., et al. (2007). Predicting workplace aggression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.228

Kjærvik, S. L., & Bushman, B. J. (2021). The link between narcissism and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(5), 477–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000323

Lambe, S., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Garner, E., & Walker, J. (2018). The role of narcissism in aggression and violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(2), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016650190

Lapierre, L. M., Bonaccio, S., & Allen, T. D. (2009). The separate, relative, and joint effects of employee job performance domains on supervisors’ willingness to mentor. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.005

Leckelt, M., Küfner, A. C. P., Nestler, S., & Back, M. D. (2015). Behavioral processes underlying the decline of narcissists’ popularity over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 856–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000057

Leunissen, J. M., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2017). Why narcissists are unwilling to apologize: The role of empathy and guilt. European Journal of Personality, 31(4), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2110

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). Springer.

Liu, D., Liao, H., & Loi, R. (2012). The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0400

Mackey, J. D., McAllister, C. P., Ellen, B. P., III., & Carson, J. E. (2021). A meta-analysis of interpersonal and organizational workplace deviance research. Journal of Management, 47(3), 597–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319862612

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R., & Mackey, J. D. (2013). A review of abusive supervision research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(Suppl. 1), S120–S137. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1888

May, D., Wesche, J. S., Heinitz, K., & Kerschreiter, R. (2014). Coping with destructive leadership: Putting forward an integrated theoretical framework for the interaction process between leaders and followers. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 222(4), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000187

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1159

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1

Nevicka, B., De Hoogh, A. H. B., Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2018). Narcissistic leaders and their victims: Followers low on self-esteem and low on core self-evaluations suffer most. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00422

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lee, J. Y. (2003). The mismeasure of man(agement) and its implications for leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 615–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.08.002

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 555–572. https://doi.org/10.2307/256693

Schilling, J., & May, D. (2015). Negative und destruktive Führung. In J. Felfe (Ed.), Trends der psychologischen Führungsforschung (pp. 317–330). Hogrefe.

Schilling, J., Schyns, B., & May, D. (2022). When your leader just does not make any sense: Conceptualizing inconsistent leadership. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05119-9

Schyns, B., Gauglitz, I. K., Wisse, B., & Schütz, A. (2022). How to mitigate destructive leadership—Human resources-practices that mitigate Dark Triad leaders’ destructive tendencies. In D. Lusk & T. Hayes (Eds.), Overcoming bad leadership: In organizations A handbook for leaders, talent management professionals, and psychologists. Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.09.001

Schyns, B., Gauglitz, I. K., Gilmore, S., & Nieberle, K. (2023). Vulnerable narcissistic leadership meets Covid-19: The relationship between vulnerable narcissistic leader behaviour and subsequent follower irritation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2023.2252130

Simon, L. S., Hurst, C., Kelley, K., & Judge, T. A. (2015). Understanding cycles of abuse: A multimotive approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1798–1810. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000031

Spain, S. M., Harms, P., & LeBreton, J. M. (2014). The dark side of personality at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, S41–S60. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1894

Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 845–851. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.845

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556375

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300812

Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500

Tett, R. P., & Guterman, H. A. (2000). Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross-situational consistency: Testing a principle of trait activation. Journal of Research in Personality, 34(4), 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2000.2292

Tett, R. P., Toich, M. J., & Ozkum, S. B. (2021). Trait activation theory: A review of the literature and applications to five lines of personality dynamics research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 199–233. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062228

Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007

Waldman, D. A., Wang, D., Hannah, S. T., Owens, B. P., & Balthazard, P. A. (2018). Psychological and neurological predictors of abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 71, 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12262

West, S. G., Aiken, L. S., & Krull, J. L. (1996). Experimental personality designs: Analyzing categorical by continuous variable interactions. Journal of Personality, 64(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00813.x

Whitman, M. V., Halbesleben, J. R., & Shanine, K. K. (2013). Psychological entitlement and abusive supervision: Political skill as a self-regulatory mechanism. Health Care Management Review, 38(3), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182678fe7

Wisse, B., & Sleebos, E. (2016). When the dark ones gain power: Perceived position power strengthens the effect of supervisor Machiavellianism on abusive supervision in work teams. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 122–126.

Yukl, G., & Gardner, W. L. (2019). Leadership in organizations (9th ed.). Pearson.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix