Abstract

This article provides an analysis of the ethical behavior of managers making goodwill impairment decisions following the adoption of the International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 3 on Business Combinations. Replacing the systematic amortization of goodwill with the impairment-only approach has been a highly controversial step. Although the aim of IFRS 3 was to provide users with more value-relevant information regarding the underlying economics of the business, it has been criticized for the potential earnings management inherent in impairment testing. This study is based on a sample of Spanish-listed companies between 2005 and 2011, a period that embraces the economic crisis. After controlling for the underlying economic factors of the firms, the results suggest that managers are exercising discretion in the reporting of goodwill impairment losses, and big bath and smoothing strategies are influencing the decisions, whether or not to impair goodwill and about the magnitude of the impairment. Firm size is an attribute that appears significant in the analysis, suggesting that the cost and complexity of running the impairment test affect managers’ decisions. Additional analyses suggest that the macroeconomic environment influences opportunistic and unethical behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Using principal components analysis of several financial structure indicators, Bijlsma and Zwart (2013) clustered EU countries into groups. Austria, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain are included in the bank-based group, and The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Finland, and Sweden in the market-based one. Whereas other EU countries do not fit well in any of these groups, this breakdown confirms that the traditional classification that serves as the basis of the so-called continental vs Anglo-American accounting systems is still valid (Nobes 1983).

In this section, we refer to IFRS 3 (IASB 2004a) and IAS 36 (IASB 2004b), which is the accounting regulation that affects EU countries. Despite some differences in the specific impairment rules, the first step, including the estimation of the fair value of the cash-generating unit (CGU) in order to appreciate if an impairment should be recorded, is basically consistent with the related USGAAP—Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) 141 (FASB 2001a) and 142 (FASB 2001b).

IFRS 3 requires that acquired assets, liabilities, and contingent liabilities are recognized at fair value by the acquirer if they satisfy the recognition criteria, whether or not they have been recognized previously. Any difference between the purchase price and the total fair value of the identifiable net assets should be recognized as goodwill (IASB 2004a, IFRS 3, para. 36).

EFRAG advises the EU prior to the adoption of IFRS (see Richardson and Eberlein 2011). The IFRS 3 endorsement letter is available at http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/accounting/committees/efrag_endorsement_advices_en.html.

These authors discuss the adoption of SFAS 141 and SFAS 142 as a case of macro-manipulation and maintain: “In order to be able to introduce the standard eliminating pooling FASB had to make a major concession by removing the requirement to amortize goodwill, thus creating an opportunity for some creative earnings management at the individual company level” (Gowthorpe and Amat 2005, p. 60).

The big-bath strategy consists of a one-time overstatement of charges against income to reduce assets, which reduces future expenses and increases future income accordingly. The expectation is that the loss is discounted in the market by analysts and investors who will focus on future earnings.

This approach provides consistent, asymptotically efficient coefficient estimates despite the correlation of the residuals across the two processes—the decision to have a goodwill impairment and the equation of interest.

In the absence of exclusion restrictions, the results for the inverse Mills ratio depend entirely on its nonlinearity; this aspect is an issue because theory rarely suggests what the correct functional form is. Thus, the coefficients of the variables included in both models would not be properly estimated due to multicollinearity problems when there are no variables excluded in the OLS (Lennox et al. 2012).

Income smoothing is normally seen as an instrument for reducing transparency, but, as Chih et al. (2008) have noted, some scholars take the opposite view, arguing that more valuable information is conveyed to uninformed investors by lowering earnings volatility.

Under the extremely restrictive assumption that firms have only one CGU and that the market value of the outstanding shares captures its recoverable amount, this contingency analysis may imply a high level of noncompliance with the impairment test requirements. A similar conclusion was obtained by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) after analyzing the accounting practices of 235 issuers: “ESMA found that significant impairment losses of goodwill recognized in 2011 were limited to a handful of issuers, particularly in the financial services and telecommunication industry” (ESMA 2013, p. 3). The report is available at http://www.esma.europa.eu/system/files/2013-02.pdf.

In the second stage, the sample sizes for the two subperiods are small, as there are few observations with impairment—33 and 71, respectively—which does not allow us to run a regression with 10 independent variables. We have performed a Tobit analysis as an alternative solution; it includes 213 and 325 observations in each of the two subperiods, although that does not allow us to separate the two decisions.

Similarly, Reverte (2009) concludes that the factors influencing the corporate social responsibility disclosure practices of Spanish-listed companies are not significantly different from the factors that influence them in other environments.

Abbreviations

- CGU:

-

Cash-generating unit

- EU:

-

European Union

- EUR:

-

Euro

- EFRAG:

-

European Financial Reporting Advisory Group

- ESMA:

-

European Securities and Markets Authority

- FASB:

-

Financial Accounting Standards Board

- GAP:

-

General accounting plan

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- IAS:

-

International Accounting Standards

- IASB:

-

International Accounting Standards Board

- IFRS:

-

International Financial Reporting Standards

- IOS:

-

Investment opportunity set

- M&A:

-

Mergers and acquisitions

- OLS:

-

Ordinary least squares

- SFAS:

-

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

- USA:

-

United States of America

- USD:

-

United States Dollar

- USGAAP:

-

United States generally accepted accounting principles

References

AbuGhazaleh, N. M., Al-Hares, O., & Roberts, C. (2011). Accounting discretion in goodwill impairments: UK evidence. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 22(3), 165–204.

Amir, E., Harris, T. S., & Venuti, E. K. (1993). A comparison of the value-relevance of U.S. versus non-U.S. GAAP accounting measures using form 20-F reconciliations. Journal of Accounting Research, 31(supplement), 230–264.

Amstrong, R. W. (1996). The relationship between culture and perception of ethical problems in international marketing. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(11), 1199–1208.

Arnold, D. F., Bernardi, R. A., Neidermeyer, P. E., & Schmee, J. (2007). The effect of country and culture on perceptions of appropriate ethical actions prescribed by codes of conduct: A western European perspective among accountants. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(4), 327–340.

Ayers, B., Lefanowicz, C., & Robinson, J. (2000). The financial statement effects of eliminating the pooling-of-interests method of acquisition accounting. Accounting Horizons, 14(1), 1–19.

Barth, M. E., & Clinch, G. (1996). International accounting differences and their relation to share prices: Evidence from U.K., Australian, and Canadian firms. Contemporary Accounting Research, 13(1), 135–170.

Beatty, A., & Weber, J. (2006). Accounting discretion in fair value estimates: An examination of SFAS 142 goodwill impairments. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(2), 257–288.

Bens, D., Heltzer, W., & Segal, B. (2011). The information content of goodwill impairments and SFAS 142. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 26(3), 527–555.

Bijlsma, M. J., & Zwart, G. T. J. (2013). The changing landscape of financial markets in Europe, the United States and Japan. Bruegel working paper. http://www.bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/774-the-changing-landscape-of-financial-markets-in-europe-the-united-states-and-japan/.

Bradbury, M. E., Godfrey, J. M., & Koh, P. S. (2003). Investment opportunity set influence on goodwill amortization. Asia Pacific Journal of Accounting and Economics, 10, 57–79.

Brochet, F., & Welch, K. T. (2011). Top executive background and financial reporting choice: The case of goodwill impairment. Harvard Business School research paper no. 1765928. Available at SSRN http://ssrn.com/abstract=1765928.

Cai, L., Rahman, A., & Courtenay, S. (2014). The effect of IFRS adoption conditional upon the level of pre-adoption divergence. The International Journal of Accounting, 49(2), 147–178.

Callao, S., & Jarne, J. I. (2011). El impacto de la crisis en la manipulación contable. The impact of the crisis on earnings management. Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review, 14(2), 59–85.

Carlin, T. M., & Finch, N. (2010). Evidence on IFRS goodwill impairment testing by Australian and New Zealand firms. Managerial Finance, 36(9), 785–798.

Chalmers, K., Clinch, G., & Godfrey, J. M. (2008). Adoption of international financial reporting standards: Impact on the value. Australian Accounting Review, 18(3), 237–248.

Chalmers, K. G., Godfrey, J. M., & Webster, J. C. (2011). Does a goodwill impairment regime better reflect the underlying economic attributes of goodwill? Accounting and Finance, 51, 634–660.

Cheng, C. S. A., Ferris, K. R., Hsieh, S., & Su, Y. (2005). The value relevance of earnings and book value under pooling and purchase accounting. Advances in Accounting, 21, 25–59.

Chih, H., Shen, C., & Kang, F. (2008). Corporate social responsibility, investor protection, and earnings management: Some international evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1–2), 179–198.

Choi, T. H., & Pae, J. (2011). Business ethics and financial reporting quality: Evidence from Korea. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(3), 403–427.

Comiskey, E. E., & Mulford, C. W. (2010). Goodwill, triggering events, and impairment accounting. Managerial Finance, 36(9), 746–767.

Dhrymes, P. J. (1986). Limited dependent variables. In Z. Griliches & M. D. Intriligator (Eds.), Handbook of econometrics (Vol. III, pp. 1567–1631). Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Elliott, J. A., & Shaw, W. H. (1988). Write-offs as accounting procedures to manage perceptions. Journal of Accounting Research, 26(Suppl.), 91–119.

Ernst & Young. (2009). Acquisitions accounting—What s next for you? A global survey of purchase price allocation practices.

European Accounting Association. Financial Reporting Standards Committee (EAA FRSC). (2014). Response to the IASB discussion paper a review of the conceptual framework for financial reporting. http://www.ifrs.org/Current-Projects/IASB-Projects/Conceptual-Framework/Discussion-Paper-July-2013/Pages/Comment-letters.aspx.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2001a). Business combinations Statement of financial accounting standards no. 141. Stanford, CT: Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2001b). Goodwill and other intangible assets. Statement of financial accounting standards no. 142. Stanford, CT: Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Fischer, M., & Rosenzweig, K. (1995). Attitudes of students and accounting practitioners concerning the ethical acceptability of earning management. Journal of Business Ethics, 14(6), 433–444.

Francis, J., Hanna, D., & Vincent, L. (1996). Causes and effects of discretionary asset write-offs. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(Supplement), 117–134.

Frecka, T. J. (2008). Ethical issues in financial reporting: Is intentional structuring of lease contracts to avoid capitalization unethical? Journal of Business Ethics, 80(1), 45–59.

Gill de Albornoz, B., & Alcarria, J. (2003). Analysis and diagnosis of income smoothing in Spain. European Accounting Review, 12(3), 443–463.

Giner, B., & Gallén, M. L. (2005). La alteración del resultado a través del análisis de distribución de frecuencias. Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 34(124), 141–181.

Giner, B., & Pardo, F. (2007). La relevancia del fondo de comercio y su amortización en el mercado de capitales: una perspectiva europea. Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 36(134), 389–415.

Glaum, M., Schmidt, P., Street, D. L., & Vogel, S. (2013). Compliance with IFRS 3- and IAS 36-required disclosures across 17 European countries: company- and country-level determinants. Accounting and Business Research, 43(3), 163–204.

Godfrey, J. M., & Koh, P. S. (2009). Goodwill impairment as a reflection of investment opportunities. Accounting and Finance, 49, 117–140.

Goergen, M., & Renneboog, L. (2004). Shareholders wealth effects of European domestic and cross-border takeover bids. European Financial Management, 10(1), 9–45.

Gowthorpe, C., & Amat, O. (2005). Creative accounting: Some ethical issues of macro- and micro-manipulation. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(1), 55–64.

Hail, L., Leuz, C., & Wysocki, P. (2010). Global accounting convergence and the potential adoption of IFRS by the U.S. (Part I): Conceptual underpinnings and economic analysis. Accounting Horizons, 24(3), 355–394.

Hamberg, M., Paananen, M., & Novak, J. (2011). The adoption of IFRS 3: The effects of managerial discretion and stock market reactions. European Accounting Review, 20(2), 263–288.

Hayn, C. (1995). The information content of losses. Journal of Accounting Research, 20, 125–153.

Hayn, C., & Hughes, P. (2006). Leading indicators of goodwill impairment. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 21, 223–265.

Healy, P. M., & Wahlen, J. M. (1999). A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 365–383.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Henning, S. L., Lewis, B. L., & Shaw, W. L. (2000). Valuation of the components of purchased goodwill. Journal of Accounting Research, 38(1), 375–386.

Henning, S., & Shaw, W. (2003). Is the selection of the amortization period for goodwill a strategic choice? Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 20, 315–333.

Henning, S. L., Shaw, W. H., & Stock, T. (2004). The amount and timing of goodwill write-offs and revaluations: Evidence from U.S. and U.K. firms. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 23, 99–121.

Hirschey, M., & Richardson, V. J. (2003). Investor underreaction to goodwill write-offs. Financial Analysts Journal, 59(6), 75–84.

Hoogerworst, H. (2012a). The imprecise world of accounting. IAAER conference, Amsterdam. www.iasplus.com.

Hoogerworst, H. (2012b). The concept of prudence: Dead or alive? FEE conference on corporate reporting of the future, Brussels. www.iasplus.com.

Hopkins, P. E., Houston, R. W., & Peters, M. F. (2000). Purchase, pooling and equity analysts’ valuation judgments. The Accounting Review, 75(3), 257–281.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2004a). Business combinations. Part A. International financial reporting standard no. 3. London: IASCF. March.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2004b). Impairment of assets. Part A. International accounting standard no. 36 (revised 2004). London: IASCF. March.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2004c). Impairment of assets. Part B. International accounting standard no. 36 (revised 2004). London: IASCF. March.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2009). International financial reporting standard for small and medium-sized entities (SMEs). London: IASCF. July.

International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC). (1998). Business combinations. International accounting standard no. 22 (revised 1998). London: IASC.

Jarva, H. (2009). Do firms manage fair value estimates? An examination of SFAS 142 goodwill impairments. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 36(9&10), 1059–1086.

Jennings, R., LeClere, M. J., & Thompson, R. B, I. I. (2001). Goodwill amortization and the usefulness of earnings. Financial Analysts Journal, 57(5), 20–28.

Jo, H., & Kim, Y. (2008). Ethics and disclosure: A study of the financial performance of firms in the seasoned equity offerings market. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(4), 855–878.

Jordan, C. E., Clark, S. J., & Vann, C. E. (2007). Using goodwill impairment to effect earnings management during SFAS no. 142’s year of adoption and later. Journal of Business & Economic Research, 5(1), 23–30.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastuzzi, M. (2013). The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) project. www.govindicators.org.

Kirschenheiter, M., & Melumad, N. (2002). Can “big bath” and earnings smoothing co-exist as equilibrium financial reporting strategies? Journal of Accounting Research, 40(3), 761–796.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113–1155.

Labelle, R., Gargouri, R. M., & Francouer, C. (2010). Ethics, diversity management, and financial reporting quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 335–353.

Lapointe-Antunes, P., Cormier, D., & Magnan, M. (2009). Value relevance and timeliness of transitional goodwill-impairment losses: Evidence from Canada. The International Journal of Accounting, 44, 56–78.

Lee, C. (2011). The effect of SFAS 142 on the ability of goodwill to predict future cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 30, 236–255.

Lennox, C. S., Francis, J. R., & Wang, Z. (2012). Selection models in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 589–616.

Leuz, C. (2010). Different approaches to corporate reporting regulation: How jurisdictions differ and why. Accounting and Business Research, 40(3), 229–256.

Li, Z., Shroff, P. K., Venkataram, R., & Zhang, I. X. (2011). Causes and consequences of goodwill impairment losses. Review of Accounting Studies, 16(4), 745–778.

Li, K. K., & Sloan, R. (2011). Has goodwill accounting gone bad? Working paper. University of Toronto. Available at SSRN http://ssrn.com/abstract=1803918.

Liberatore, G., & Mazzi, F. (2010). Goodwill write-off and financial market behaviour: An analysis of possible relationships. Advances in Accounting, Incorporating Advances in International Accounting, 26, 333–339.

Lin, Z., & Shih, M. S. H. (2002). Earnings management in economic downturns and adjacent periods: evidence from the 1990–1991 recession. Working paper. National University of Singapore.

Lys, T., & Vincent, L. (1995). An analysis of value destruction in AT&T’s acquisition of NCR. Journal of Financial Economics, 39, 353–378.

Masters-Stout, B., Costigan, M. L., & Lovata, L. M. (2008). Goodwill impairments and chief executive officer tenure. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19, 1370–1383.

Merchant, K., & Rockness, J. (1994). The ethics of managing earnings: An empirical investigation. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 13, 79–94.

Moehrle, S. R., Reynolds-Moehrle, J. A., & Wallace, J. S. (2001). How informative are earnings numbers that exclude goodwill amortization? Accounting Horizons, 15(3), 243–255.

Morricone, S., Oriani, R., & Sobrero, M. (2009). The value relevance of intangible assets and the mandatory adoption of IFRS. Available at SSRN http://ssrn.com/abstract=1600725.

Nobes, C. W. (1983). A judgmental international classification of financial reporting practices. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 10(1), 1–19.

Parte, L. (2008). The hypothesis of avoiding losses and decreases in earnings via extraordinary items. Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 37(139), 405–440.

Petersen, C., & Plenborg, T. (2010). How do firms implement impairment tests of goodwill? Abacus, 46(4), 419–446.

Ramanna, K. (2008). The implications of unverifiable fair-value accounting: Evidence from the political economy of goodwill accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2–3), 253–281.

Ramanna, K., & Watts, R. L. (2012). Evidence on the use of unverifiable estimates in required goodwill impairment. Review of Accounting Studies, 17(4), 749–780.

Rees, L., Gill, S., & Gore, R. (1996). An investigation of asset write-downs and concurrent abnormal accruals. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(Suppl.), 157–169.

Reverte, C. (2009). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by Spanish listed firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(2), 351–366.

Richardson, A. J., & Eberlein, B. (2011). Legitimating transnational standard-setting: The case of the International Accounting Standards Board. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(2), 217–245.

Riedl, E. (2004). An examination of long-lived asset impairments. The Accounting Review, 79, 823–852.

Rockness, H., & Rockness, J. (2005). Legislated ethics: From Enron to Sarbanes-Oxley, the impact on corporate America. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(1), 31–54.

Saastamoinen, J., & Pajunen, K. (2012). Goodwill impairment losses as managerial choices. Working paper. University of Eastern Finland. Available at SSRN http://ssrn.com/abstract=2000690.

Sevin, S., & Schroeder, R. (2005). Earnings management: Evidence from SFAS No. 142 reporting. Managerial Auditing Journal, 20(1), 47–54.

Smith, A., & Hume, E. C. (2005). Linking culture and ethics: A comparison of accountants’ ethical belief systems in the individualism/collectivism and power distance contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(3), 209–220.

Stokes, D. J., & Webster, J. (2009). The value of high quality auditing in enforcing and implementing IFRS: The case of goodwill impairment (January, 14). Finance and corporate governance conference 2010 paper. Available at SSRN http://ssrn.com/abstract=1536832.

Strong, J. S., & Meyer, J. R. (1987). Asset writedowns: managerial incentives and security returns. The Journal of Finance, 42, 643–661.

Sutthachai, S., & Cooke, T. E. (2009). An analysis of Thai financial reporting practices and the impact of the 1997 economic crisis. Abacus, 45(4), 493–517.

Thomson Reuters. (2011). Mergers & acquisitions review, financial advisors, first quarter. https://thomsonone.com.

Vanza, S., Wells, P., & Wright, A. (2011). Asset impairment and the disclosure of private information (March). Available at SSRN http://ssrn.com/abstract=1798168.

Verriest, A., & Gaeremynck, A. (2009). What determines goodwill impairment? Review of Business and Economics, 54(2), 106–128.

Walker, M. (2010). Accounting for varieties of capitalism: The case against a single set of global accounting standards. The British Accounting Review, 42(3), 137–152.

Watts, R. (2003). Conservatism in accounting part I: Explanations and implications. Accounting Horizons, 17, 207–223.

Wilson, G. (1996). Discussion write-offs: Manipulation or impairment? Journal of Accounting Research, 34, 171–177.

Xu, W., Anandarajan, A., & Curatola, A. (2011). The value relevance of goodwill impairment. Research in Accounting Regulation, 23, 145–148.

Zang, Y. (2008). Discretionary behavior with respect to the adoption of SFAS no. 142 and the behavior of security prices. Review of Accounting and Finance, 7, 38–68.

Zucca, L. J., & Campbell, D. R. (1992). A closer look at discretionary writedowns of impaired assets. Accounting Horizons, 6(3), 30–41.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers as well as to Juan Sanchis for their very constructive comments. We also appreciate comments on earlier versions of this paper from participants at the EAA Conference in Paris, as well as from workshop participants at the Audit and Accounting Convergence Conference in Cluj and the University College Dublin. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial contribution of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (research project ECO2013-48208-P).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Institutional Characteristics

Spain | United Kingdom | European Union (*) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Bank—intermediate credit | 0.82 | 0.33 | 0.45 |

Equity funding—stock market capitalization | 0.88 | 1.16 | 0.67 |

Equity funding—issuance of shares | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

Anti-directors’ rights | 4.00 | 5.00 | 2.60 |

Rule of law (1) | 7.80 | 8.57 | 9.04 |

Rule of law (2) | 1.14 | 1.68 | 1.50 |

Regulatory quality | 1.18 | 1.72 | 1.42 |

Control of corruption | 1.08 | 1.69 | 1.56 |

Appendix 2. Announced Mergers & Acquisitions in Spain

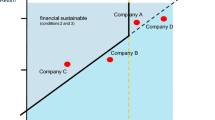

See Fig. 1.

Analysis of Thomson Financial, Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances (IMAA). Available at http://www.imaa-institute.org/statistics-mergers-acquisitions.html

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giner, B., Pardo, F. How Ethical are Managers’ Goodwill Impairment Decisions in Spanish-Listed Firms?. J Bus Ethics 132, 21–40 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2303-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2303-8