Abstract

In recent decades, huge technological changes have opened up possibilities and potentials for new socio-technological forms of violence, violation and abuse, themselves intersectionally gendered, that form part of and extend offline intimate partner violence (IPV). Digital IPV (DIPV)—the use of digital technologies in and for IPV—takes many forms, including: cyberstalking, internet-based abuse, non-consensual intimate imagery, and reputation abuse. IPV is thus now in part digital, and digital and non-digital violence may merge and reinforce each other. At the same time, technological and other developments have wrought significant changes in the nature of work, such as the blurring of work/life boundaries and routine use of digital technologies. Building on feminist theory and research on violence, and previous research on the ethics of digitalisation, this paper examines the ethical challenges raised for business, workplaces, employers and management by digital IPV. This includes the ethical challenges arising from the complexity and variability of DIPV across work contexts, its harmful impacts on employees, productivity, and security, and the prospects for proactive ethical responses in workplace policy and practice for victim/survivors, perpetrators, colleagues, managers, and stakeholders. The paper concludes with contributions made and key issues for the future research agenda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV), the theme of this special issue, is an intersectionally gendered problem worldwide,Footnote 1 with women and girls the overwhelming majority of victim/survivors.Footnote 2 An increasingly significant aspect of IPV is technology-related (Bailey et al., 2021; Barter & Koulu, 2021; Jane, 2016; Phippen & Brennan, 2021). As with IPV generally, digital IPV (DIPV)—the use of digital technologies in and for abusing and violating intimate (ex-) partnersFootnote 3— raises multiple ethical challenges for businesses,Footnote 4 employing organisations and workplaces.Footnote 5 It is these ethical challenges that DIPV brings into the workplace—with the complexity and variability of DIPV, its harmful impacts, and the prospects for proactive responses—that we interrogate in this paper.

DIPV overlaps with some ‘technologically-facilitated’ sexual violence, and even some workplace violence. We locate DIPV within long-established studies of IPV, gender-based violence (GBV), and violence against women and girls (VAWG) (Cockburn, 2004; Hanmer & Maynard, 1987; Hearn, 1998; Kelly, 1988; Lewis, 2004).Footnote 6 This paper considers the intersection of DIPV and workplace dynamics, specifically the ethical challenges of digital IPV for workplaces, employers, management, human resources (HR), supervisors, colleagues, IT staff, and organisational actors generally. These include developing ethical organisational policy and practice in relation to victims/survivors, perpetrators, colleagues, managers, board members, and wider stakeholders. Preventing and responding to DIPV in and around workplaces is a strategic and leadership issue, including employer’s responsibilities for employee safety and well-being, and a matter of organisational culture and practice.

IPV and DIPV are widespread. At their heart lie attempts to exert intersectionally gendered power and control. It has long been recognised that violence is not only directly physical but can also be verbal, image-based, psychological, emotional, and written, yet with physical effects, and, as MacKinnon (1993) famously put it, not ‘only words’. Similarly, perpetrators of IPV use various forms of abuse—physical, emotional, sexual, economic, financial, and technological—to control, frighten, isolate and monitor their partner and to erode their autonomy and freedom. Considered in a long-term historical context, understandings of and interventions against IPV have gradually broadened from direct physical and sexual violence to psychological and emotional abuse and coercive controls (Stark, 2009), such as control of friends, family, food, finances, health, and reproduction, leading onto physical and emotional harms. Prevention or impeding of work or study is a common form of economic abuse, resulting in victim/survivor’s deprivation of economic or financial resources.Footnote 7

Technology, in a broad sense, figures in the enactment of IPV, if not always named explicitly. First, the body, and indeed the self, themselves are or can be seen as technologies for deployment in violence (arms, hands/fists, legs, feet, head, torsos, and so on); second, weapons, including sticks, canes, rope, guns, knives, as well as less purpose-built items, such as kitchen equipment, telephones, sports equipment, can be used to abuse directly and physically. Digital IPV is thus more specific than referencing the generic concept of ‘technology’, that, as feminist and other analyses have noted, includes non-digital technologies, such as domestic technologies (Pantzar, 1997; Wajcman, 2010). The development and ubiquity of information and communication technologies (ICTs)—such as smart phones, laptops, tablets, audio, visual and video recording, spyware and surveillance equipment—have massively extended the potential for abusers to exert power and control. However, it is humans, exploiting technological (socio-) affordances, not disembodied technologies, who violate. Indeed, the very concept of technological affordances is much contested (e.g., Markus & Silver, 2008; Parchoma, 2014), with distinctions between, for example, functional, actual, potential affordances (Mora et al., 2021). We see the concept as most useful when understood socially and relationally (Neves & Mead, 2021), hence the term, socio-affordances.

The use of digital technologies in violating and abusing intimate (ex-) partners—DIPV—has been well studied in prior work on IPV (Al-Alosi, 2017; Douglas et al., 2019; Dragiewicz et al., 2018; Duerksen & Woodin, 2019; Freed et al., 2017, 2018, 2019; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018; Henry et al., 2020; Mathews et al., 2017; Taylor & Xia, 2018). Much of that work has been mainly directed to personal, domestic, and social life, less to the challenges for business and workplaces. IPV can spread from in-real-life (IRL) physical, sexual and emotional coercive controls, and from domestic, private and leisure times and places, into workplaces and work domains, spatially and temporally, with consequent physical and emotional effects, and impacting work-life/family relations. DIPV can be perpetrated at work, by a manager, colleague, client, or other stakeholder. Furthermore, work is conducted both at physical workplaces and at home, as well as other locations. We emphasise that work and home are not separate entities, neither physically nor experientially (Niemistö et al., 2021; Nippert-Eng, 1996; Hochschild, 1997). DIPV can be easy to perpetrate, pervasive, mobile, in perpetuity. It impacts both the primary target and others associated with them, including employers and workplace colleagues, and indeed be carried out by employers, employees or someone related to the workplace, thereby creating ethical responsibilities in work contexts. Impacts and ethical challenges are thereby intimately interconnected.

Amongst the wealth of scholarship about IPV, there is a growing literature on their connections with access to employment and the workplace (Swanberg et al., 2005; Woodlock et al., 2020), differential workplace support (Bennett et al., 2019; Pachner et al., 2021; Wibberley et al., 2018) and possible interventions (Adhia et al., 2019; Giesbrecht, 2022; Lassiter et al., 2021). However, knowledge about the impacts of DIPV on workplaces, its intersections with workplace dynamics, and the ethical challenges arising is less developed, and this is where we seek to contribute. In this paper, we thus address the following two-part research question:

What ethical challenges are raised for businesses and workplaces, including for ethical organisational policy and practice, by the spread of digital intimate partner violence?

But, first, we discuss what DIPV is, and set out our theoretical framework, before turning to the ethical challenges for workplaces. The paper concludes with the main contributions, including key issues for the future research agenda.

What is Digital Intimate Partner Violence?

The huge technological changes of recent years, along with impacts of the COVID pandemic, mean that much communication is no longer face-to-face, by letter or telephone, but is digitalised, opening up potential for new socio-technological forms of DIPV, at a distance, physically and sometimes temporally separated, whether at home, at work, or elsewhere. Freed et al., (2018, p. 667) suggest ‘cyber intimate partner victimisation’ includes: online harassment, doxxing, cyberbullying, cyberstalking, release of sensitive information about victim/survivors, non-consensual intimate imagery (NCII) and image-based sexual abuse (IBSA) (Henry et al., 2017; McGlynn & Rackley, 2017). DIPV also includes: reputation abuse (Langlois & Slane, 2017), abuse via banking (e.g., abusive messages on bank statements via tiny money transfers), hacking, (s)extortion, electronic sabotage, spycamming (Woodlock et al., 2020), deep fakes (Maddocks, 2020), and online impersonation (Sambasivan et al., 2019).

Fernet et al.’s (2019) systematic literature review identified two main categories of ‘cyber intimate partner victimisation’—or DIPV: direct and indirect. Direct online IPV refers to the use of technology directed at the (ex-) partner in a private context which the perpetrator does not intend others to witness—including stalking, harassment, sexual online IPV, pressure or threats to send/receive messages (written, audio, photographic, video) with sexual content. Indirect DIPV is the dissemination of sexual or non-sexual content in a social or public setting. The intention is to embarrass, shame, humiliate, ridicule, intimidate or in some other way harm the victim in front of family, friends and colleagues, and acquaintances, those visiting a website or social media forum, or a more diffuse, unknown, imagined audience. An example of indirect abuse is the distribution, or sharing, without consent, of genuine or fake sexually explicit images of someone else by (ex-) partners. These may be posted on dedicated forums after sexual encounters or relationships, within or at the end of longer-term intimate relationships, by those who have hacked personal e-devices, or those who have turned publicly available non-intimate images into sexualised images and videos via deep fake technologies (Hall et al., 2022).

These two forms, direct and indirect, do not exhaust the possibilities of DIPV, with new forms continually appearing, for example, via virtual reality and augmented reality (Hall et al., 2022). While DIPV perpetrators often employ widely available technologies, more specialist and purpose-built technologies are increasingly available. These include the IoT, with embedded sensors and software, connected and exchanging data with other devices and systems, with the potential for ‘IoT-enabled technology-facilitated abuse’ (Slupska & Tanczer, 2021).

It is difficult to be precise regarding DIPV prevalence rates (Hall & Hearn, 2017); however, we know that common features of abusive behaviour such as stalking and harassment (Freed et al., 2018; Lenhart et al., 2016) are increasingly enacted via digital technologies (Harris & Woodlock, 2019). A survey of 442 frontline Australian domestic violence (DV) practitioners on perpetrators’ use of technology found a 28% increase in text messaging 2015–2020, 183% increase in video camera use, and 131% increase in global positioning system (GPS) tracking device use (Woodlock et al., 2020, p. 2). Refuge (2020), the UK domestic violence charity, found in 2019 that 72% of their service users had experienced abuse through technology, and 85% of respondents surveyed by Women’s Aid UK (2020) in 2015 reported the abuse received online from a (ex-) partner was part of a pattern of abuse experienced offline (Hadley, 2017). Such DIPV can cause victim/survivors to experience constant fear, and sometimes feel obliged to turn their mobile devices on all the time “or else they were seen by the perpetrator as having something to hide” (Woodlock et al., 2020, p. 19). Much IPV is now both offline and online, often merging with and reinforcing each other.

Over the last five decades or so, activists, scholars, and policy-makers have focused on justice systems (civil and criminal) to provide key responses to IPV. However, despite these efforts, the failings of justice systems are evident, especially for racialised and marginalised groups (e.g., LGBTIQA + people, people in poverty, indigenous people) (Douglas, 2017; Gangoli et al., 2019; McGlynn & Westmarland, 2019; Porter, 2018). In response, a growing chorus of scholars and activists (see Richie, 2015; Tolmie, 2018) argues for moving away from established justice systems. In this, workplaces can play a positive role. As being employed may provide some protection against DIPV (Beecham, 2014; Rothman et al., 2007; Walby & Towers, 2018), workplaces can assist in preventing DIPV, protecting victims, and challenging perpetrators, with well-formulated organisational policy processes and practices. In addition, even though cultures are hard to change, work on workplace culture needs to include and commit all, from management to shopfloor, in creating a workplace climate with zero-tolerance for DIPV and other violations. Indeed, without a clear ethical approach, workplaces can also exacerbate DIPV. Having said that, re-analysis of the EU FRA (EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014a, b) data shows no necessary association, at the macro-level, between national employment rates and disclosed prevalence of VAW (Humbert et al., 2021).

Reliable information about who perpetrates and experiences DIPV in relation to workplaces, across different contexts, is still limited. However, research on IBSA shows 16–39-year-old men to be perpetrators more often than women of that age, with ratios of one in five and one in eight, respectively, and LGBTIQA + people reporting relatively higher victimisation (Powell et al., 2020). Dedicated ‘revenge porn’ sites have 90 or more percent men users (Hall & Hearn, 2017; Hall et al., 2022), and one recent estimate reported women as 27 times more likely to be harassed online than men.Footnote 8 While DIPV affects all ages, Marganski and Melander (2018) note that young adults have the highest rates of technology use and are at highest risk of DIPV (see Powell et al., 2020). In line with this, in the 28-country EU FRA (EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014a, b) study, younger women reported significantly higher rates of cyberviolence than older women. Cyberviolence is, however, broader than DIPV, as cyberviolence can be conducted by any others than (ex-) partners, too, but often it is a form of DIPV.

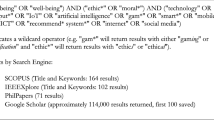

Constructing a Nested Theoretical Framework

Constructing a theoretical framework to analyse the interaction of DIPV and workplaces entails engaging with feminist and gender theories in Business, Organisation and Management Studies, in Violence Studies, and in Technology/ICT Studies, across which we as authors are placed. Thus, in studying DIPV and workplaces, an interdisciplinary, multi-theoretical approach is needed. Here, we build on our earlier individual and collective research on: gender and violence,Footnote 9 violence in organisations, corporate policy, ICTs, online communities, and resistance to violence, all intersectionally gendered. Our theoretical framework is founded on four interconnected and nested elements (see Fig. 1): diffractive transversal engagements, material-discursivity and sociomateriality, boundaries and boundarylessness, and ethical responses, all grounded in feminist theory, practice and research (Hall et al., 2022).

Diffractive, Transversal Feminist Engagements

The intertwining of multi-level feminist theorising, politics, policy, and activism is central in anti-violence work. Many strands of feminist theorising have been employed in working against violence, making too sharp distinctions between different feminisms unwise, both analytically and politically. In contrast, diffractive transversal engagement between and across feminist approaches, recognising the ethico-onto-epistemological nature of reality, has become central in contemporary feminist theorising (Barad, 2003, 2007; Collins, 2017; Haraway, 1992; Lykke, 2020; Yuval-Davis, 1997). Challenging paradigmatic incommensurability can mean reading theories on violence, on technology, and on organisations, each with their own feminist traditions, in relation to and dialogue (multilogue) with each other. For example, feminist research about violence against women (VAW) has been much influenced by radical feminism (e.g., Mackay, 2015), feminist STS (science and technology studies) and technoscience by new materialism (e.g., Barad, 2007), and feminist organisation research by gendered inequality regimes (e.g., Acker, 2006). Diffractive, transversal feminism stresses engagements between and across these and other feminist knowledges. This mirrors post-paradigmatic thinking, as long debated across the social sciences, from psychology to international relations, and including organisation theory (Willmott, 1993), and gender and organisations (see Hearn & Parkin, 1983).

Material-Discursivity and Sociomateriality

More specifically, diffractive, transversal feminist theorising emphasises material-discursivity and sociomateriality (Akrich & Latour, 1992 on material-semiotic; Hall et al., 2022; Hearn, 2014a; Haraway, 1992; Orlikowski & Scott, 2015). Although there are different approaches to material-discursivity and sociomateriality, including those drawing on socio-technical systems and actor-network theory (ANT), an important strand fits closely with diffractive transversal feminisms (as in so-called ‘new’ materialism). In this latter approach, “[m]atter is not immutable or passive” (Barad, 2003, p. 821), nor “an inert substance subject to predictable causal forces” (Coole & Frost, 2010, p. 9), but rather “a complex open system subject to emergent properties” (Hird, 2004, p. 226). Material-discursive theorising has several applications and implications for DIPV seen as a gendered, material-discursive, and emergent set of processes (Salter, 2018; Shelby, 2020; cf. Wajcman, 2010), pervasive well beyond the initial act(s), as elaborated below. Although DIPV works largely through the discursive, representational, and virtual, it has embodied, material, experiential harms and effects, as well as often occurring in association with offline IPV.

Boundaries and Boundarylessness

Material-discursive and sociomaterialist analysis in turn highlights the shifting intersectionally gendered boundaries and interfaces, and at times boundarylessness, of DIPV, across ‘intimate’ and workplace spaces. Boundaries, such as work/home-family-life boundaries, are often ambiguous even paradoxical realities (Hearn & Parkin, 2021): all too real in their powerful inclusions/exclusions yet needing problematisation and deconstruction. While paid work is increasingly dominating people’s lives in many parts of the world, work/non-work boundaries are subject to re-negotiation and highly variable in permeability, individually, collectively and organisationally (Niemistö et al., 2021; Hochschild, 1997; Nippert-Eng, 1996).

In discussing DV and organisations, Wilcox et al. (2021) usefully outline four interfaces cutting across dichotomies: ‘domestic-work’, ‘business-society’, ‘men-women’, ‘mind/rationality-body/emotion’. All four are relevant for DIPV, which transcends public–private boundaries, and thus affirms long-stablished feminist critiques of analytical separations of private and public domains (Hearn, 1992; Collins, 2000). The importance of shifting boundaries has also long been recognised in feminist work on IPV (Hanmer, 1998). Key interfaces with DIPV include home/work, offline/online, and IRL/virtual.

By appropriating socio-affordances, DIPV extends the reach and control of perpetrators, across boundaries, spatially and temporally—in forms of spacelessness, enacted with “an open space of agency” (Barad (2007, p. 179), and timelessness, combining, for example, instantaneousness with asynchronicity, sometimes delayed long-term. Indeed, Harris and Woodlock (2019, p. 530) specifically argue that ‘digital coercive control’ (or DIPV) is unique amongst gendered violence by virtue of “its spacelessness” (italics in original), and we would add and emphasise timelessness. DIPV can also employ other socio-affordances, with their own characteristics, including: concentration of control, reproducible image production, recordability, creation of virtual bodies/spaces, blurring the ‘real’ and the ‘representational’, wireless portability, globalised connectivity, conditional communality, personalisation (individually-targeted for maximum effect), and unfinished undecidability (Hearn, 2014b; Hearn and Parkin, 2001; Markus & Silver, 2008; Wellman, 2001). In this perspective, DIPV can be understood as part of long-term processes of publicisation of patriarchy (Hall & Hearn, 2017, 2019; Hearn, 1992), whereby private patriarchal life becomes reformulated as part of public patriarchal spheres that now extends to the virtual public sphere (Brantner et al., 2021; Papacharissi, 2002) through digitalisation/virtualisation.

Feminist Ethics

These theoretical perspectives frame our understanding of ethics. Ethics is not a separate, abstract field but is integral to diffractive transversal feminism connecting with ontology, epistemology, and politics, is material-discursive, and operates across boundaries (see Fig. 1). These material-discursive, sociomaterial and boundaryless features also apply to DIPV, raising major ethical challenges for workplaces and requiring feminist ethical responses. Recent literature on the ethical implications of technological change (Martin et al. 2019), including digitalisation in business, highlights such issues as: desensitising effects, work climate (Palumbo, 2021), privacy norms (Martin, 2012), and responsibility-gaps in decision-making (Johnson, 2015). Royakkers et al. (2018) discussion of the ethics of digitalisation, foregrounding positively human dignity, security, justice, privacy, autonomy, and balance of power, is especially useful.

While not specifically addressing DIPV, all these features are relevant and useful for present purposes, and translated as: freedom from DIPV (human dignity), security from DIPV, justice in preventing, stopping and dealing with DIPV, privacy and autonomy for victim/survivors of DIPV, and opposing DIPV as undoubted imbalance of power, addressed, or not, within organisations, themselves typically sites of intersectionally gendered power imbalances.Footnote 10 More positively, such an approach can be understood as a principled opposition to violence as a basis of feminist ethical practice.Footnote 11 However, translating these guidelines into contingent practice in relation to DIPV in workplaces and across work/life boundaries raises ethical challenges—and it is these we examine in the next section.

To sum up, our theoretical framework for analysing DIPV is located in feminist theory, practice and research, material-discursivity, highlighting multiple boundary-crossings, spatially and temporally, and feminist ethics of opposition to violence and of positive care. We now turn to focus on our main research question: the ethical challenges that are raised for workplaces when DIPV crosses boundaries into working life.

DIPV in and Around the Workplace: Ethical Challenges

The guidelines above, following Royakkers et al. (2018), are important regarding DIPV in and around workplaces, for victims and perpetrators, colleagues, work communities, employers, and other stakeholders, for both immediate urgent action and longer-term organisational processes. As just noted, translating these guidelines into practice in relation to DIPV raises major ethical challenges for workplaces, not least as DIPV extends across several kinds of boundaries. We see three main and interconnected kinds of ethical challenges: recognising the complexity, variability, and even elusiveness of the phenomenon of DIPV in and around workplaces; assessing the negative impacts of DIPV on workplaces; and developing proactive responses, policy and practices on DIPV in and around workplaces.

Ethical Challenges: The Complex Variable Phenomenon of DIPV in and Around Workplaces

The presence of the phenomenon of DIPV in and around workplaces is complex, variable by work context, and at times elusive to a single definition. Though DIPV is targeted, initially at least, at intimate (ex-) partners, as noted, this very easily spreads into working life in a host of possible ways. Intimate life is not isolated from the rest of social life, and, similarly, for many work contexts, drawing neat boundaries around (the walls of) organisations has become nigh on impossible. DIPV, can, at times paradoxically, be both beyond and present within the workplace. It can involve: one or more perpetrators and/or victim/survivors, who may or may not be employed in the organisation concerned; ‘external’ perpetrators, including those in another organisation, customers or clients, who may abuse an ‘internal’ victim/survivor; ‘internal’ employee-perpetrators who may abuse an ‘external’ victim/survivor. It can include perpetration before one or more of those began the employment in question. Several aspects of the phenomenon of DIPV in and around workplaces add further ethical challenges.

Variability of Forms of DIPV

A first challenging issue is the sheer multiplicity of and variability in forms of DIPV in and around workplaces, from the unseen to very widely distributed, fully public, and from, say, an ambiguous sext, forwarded without consent, to long-term online sexual oppression. As noted, DIPV can also be more indeterminate in form and content, potentially pervasive, not fully known and specifiable in advance than IPV in-real-life. This is especially so with current and future technological ‘advances’—including artificial intelligence (AI)/artificial general intelligence (AGI), deepfakes, holograms, heightened interactivity, immersive/virtual reality, and ‘Google Glasses’ technologies. The material-discursive, IRL/virtual, and emergent character of DIPV needs vigilant, contingent monitoring by workplaces and managements, with their shifting associated ethical challenges.

The spatial/temporal spread of DIPV beyond personal life and across organisational boundaries heightens those challenges. With DIPV, time is not linear or chronological,Footnote 12 and (social) space is not continuous. Acts of DIPV can be received even when (long) separated from the perpetrator, and in the middle of any other task or experience, for example, going for a job interview or in a work meeting. DIPV can occur at any moment, within, outside or in relation to work, as if within a temporal panopticon (cf. Haggerty & Ericson, 2000). The speed and ‘instant gratification’ of much technology usage in DIPV also impacts gender-sexual-embodied time, rhythms and experiences, in ways difficult to reduce to discursive construction alone.

A further complication is that, in some cases of DIPV, the victim/survivor may be unaware of messages or visuals sent by the perpetrator to colleagues or managers, even for extended periods of time. Colleagues may know, via social media, of certain violating actions even before the primary victim/survivor, raising ethical challenges regarding disclosure. This raises the question of how this is to be handled ethically, confidentially, swiftly, and with justice and safety. A situation where the victim/survivor could be humiliated within the work community, without even knowing of it, calls for a highly empathetic approach from colleagues and managers in supporting the victim/survivor-employee in a sensitive way.

DIPV may be initially enacted within or outside work hours, within or away from work premises, by devices away from work to those at work (and vice versa), and in neither physical workplaces nor during working time, but with work-related content or implications. Such different contexts and situations may change one to another, presenting shifting ethical challenges for employers, around, for example, the limits of responsibility ‘out of work hours’, the relations of on-site and off-site work, and intertwining of primary and secondary victimisation.

A concrete ethical challenge concerns the extent of ‘legitimate’ managerial responsibilities with DIPV and the limits of employer knowledge of personal, health-related, even sexual and intimate, lives of employees, beyond organisational boundaries, whilst protecting personal privacy.Footnote 13 For example, to what extent is it desired, preferred, or legitimate, for all the different relevant parties to disclose DIPV and/or maintain issues around DIPV as private and confidential? Victim/survivor employees’ and managers’ might indeed wish to hide aspects of their lives relating to DIPV from work communities, for example, to maintain an invulnerable work persona/identity/status, not be perceived as a victim or resist intrusion into personal life. Accordingly, in combining strong policy frameworks with contextual specificity, both strategic organisational positioning and specific measures on DIPV are needed in dialogue with relationship-based ethics.

Varíability of Workplaces

Second, workplaces themselves vary greatly—from employees living ‘in-house’ or where work and home co-exist, as in some family businesses or homeworking, through to strict(er) separations of work time and of home and workplace, and where employees work fixed hours, work alone, or by piecework. Such differing work conditions entail variable boundary considerations and thereby differential impacts on privacy, autonomy, and safety, and prospects for justice with imbalances of power within workplaces.

Variability of Work Content

Third, and relatedly, there is the issue of variable work content and differential access to and use of ICT devices themselves within workplaces, for perpetrating, experiencing, or learning of DIPV. A clear challenge needing firm policy is the (mis)use of work-based ICTs for DIPV, and when perpetrators are employed as in-house information technology (IT) specialists and in positions involving non-abuse of trust, power, and security. Potential negative aspects and effects here include: first, in being subjected to DIPV at work or by a colleague, the workplace context compounds the situation, as through additional workplace power dynamics; second, these effects can be exacerbated by lack of support and measures from supervisors and policy; third, when the perpetrator is themselves an expert in digital devices and digital navigation, they are more likely to be able to cover the traces of their misconduct. The experience of being a victim/survivor of DIPV can be affected, asynchronously, by immediate situational work and ICT context, including what happens before, during and after experiencing DIPV, including work situations where the formal support is actually the potential perpetrator, or a close colleague thereof. Given the complexities of temporal/spatial locations of DIPV in relation to workplaces, and varying work contexts, developing ethical policy and practice is rarely resolved by pre-given blueprints.

Ethical Challenges: The Pervasive Negative Impacts of DIPV in and Around Workplaces

DIPV in and around workplaces has many negative impacts in and around workplaces. With its complex, emergent and inherent unethical character, DIPV can pervade the workplace, arguably even more so, or at least often less visibly, than non-digital IPV. Such pervasive impacts on workplaces present ethical challenges across workplaces; impacts and ethics are intimately interrelated, and a key element in developing proactive responses. As with contemporary socio-technological changes in workplaces, such as blurring of work/non-work boundaries, extra-local and transnational working, and routine digitalisation, DIPV has multiple material-discursive, sociomaterial impacts on workplace dynamics and boundaries. The impacts of DIPV on workplaces span many possible concrete situations, across various organisational boundaries, and with differential relations of perpetrators, victim/survivors (both of whom may be employed by other organisations), colleagues, managers, as well as customers and stakeholders. DIPV, as sociomaterial enactments, brings multiple harms to and into workplaces, to individuals, work communities and workplaces, not least through its boundarylessness, spacelessness, and timelessness. Here we consider, albeit briefly, three likely and pervasive harmful impacts of DIPV in and around workplaces—on employees, productivity and profitability, and security and reputation—in addition to the harms experienced in ‘domestic’, ‘intimate’ contexts, already noted.

On Employees

Changing interfaces of both private(family/household)/public(work/employment) and IRL/online worlds make for more diffuse, easier conditions for surveillance by abusive (ex-) partners (Woodlock et al., 2020). Perpetrators may contact co-workers and managers, often key social resources for victim/survivors, to gather or share information about their victim, identify their whereabouts, disrupt victim/survivors’ work and contact with others, and instil confusion and fear (Swanberg et al., 2005). The reach of DIPV extends beyond that of some IRL, non-digital coercive controls, extending harms across time and space. As noted, initial acts of DIPV may be instant in effects, or not known until much later, or even never known to the primary victim/survivor.

Work impacts of DIPV on employees who are victim/survivors include time away from work, emotional stress at home and work, time spent seeking health and legal support, and needing to move locality to avoid or escape the perpetrator (Beecham, 2009, 2014; Harris & Woodlock, 2019; Walby, 2004; Woodlock, 2017). DIPV may disrupt education and training, and hinder victim/survivor’s chances of securing future employment. Victim/survivors report perpetrators forwarding explicit images of them to their boss and work colleagues. This may be accompanied by workplace harassment and/or resignation due to stress and embarrassment facing co-workers (Society for Human Resource Management, 2013). DIPV may lead onto homicide or suicide.

Co-workers and managers may also be impacted (Crowe, 2016). Work absence likely means increased workload for others, further stress, perhaps temporary replacements (Health & Safety Executive, 2020). The mental burden of DIPV can negatively affect work communities, with negative spillover effects between family and work domains (Crouter, 1984). Just as third-party individuals can be subject to physical violence in IPV, so may co-workers be exposed to DIPV (e.g., viewing non-consensual explicit images of a colleague, or manipulated online into giving personal information about victim/survivors), be at risk of traumatic stress, (e.g., by being ‘triggered’ to re-live their own experiences of abuse), or be indirectly exposed (e.g., listening to colleagues talk about DIPV) and subject to secondary traumatic stress and distress (Baird & Jenkins, 2003).

On Productivity and Profitability

Following the remarks above, DIPV is a workplace and business concern also in terms of productivity and profitability. For Canada, Zhang et al. (2012) estimated that employers lose $77.9 million yearly as a direct result of domestic violence. While the economic impacts of DIVP and IPV are likely to be impossible to disaggregate, DIPV can reduce productivity due to fear, anxiety, stress, and injuries which may lead to reduced concentration and increased accident risk. Co-workers’ productivity may also decrease as an indirect effect of their supporting to a victim/survivor. Costs for employers include staff turnover, agency costs for temporary staff, and installation of additional security.

On Security and Reputation

Security breaches and reputational damage through DIPV impact on employees (e.g., job satisfaction, work well‐being), customers (e.g., product quality), businesses, and stakeholders (e.g., organisational commitment, brand image) (Crowe, 2016; Kerrbach & Mignonac, 2006), rather differently to most non-digital IPV. Perpetrators of DIPV may harass with e-messages and online posts, and disclose, or threaten to disclose, passwords and sensitive information to colleagues and employers, in turn impacting employer reputation, and individuals and colleagues. Posts on IBSA-dedicated websites have contained victim/survivors’ personal information, such as address and employer, presumably so that others could damage their work reputation (Hall & Hearn, 2017, 2019). Such postings are becoming increasingly common, and the impact for victim/survivors is often discussed on social media forums, reporting devastating, life-altering effects, humiliation with colleagues, and personal reputation ruination (Lichter, 2013). Such practices can be exacerbated by managerial cultures that embody patriarchal or laissez-faire norms (through non-response) (Ågotnes et al., 2018), further threatening employer’s and employee’s security (MacQuarrie et al., 2019).

Identity theft can result in employees taking time away from work to restore their identity, losing customer loyalty, and creating security risks, and reputational damage. DIPV also impacts employer reputation in terms of being a supportive or women-friendly employer. Data security breaches, including identity theft, are amongst the top threats for organisations, with high financial costs for recovery. Changing work patterns, such as blurring of home/work and IRL/virtual interfaces, have been accentuated during COVID restrictions with associated risks to security. During the pandemic, DIPV has risen significantly with greater homeworking during lockdowns (Evans et al., 2020; Human Rights Watch, 2020).

All these impacts illustrate the material-discursive, emergent, at times boundaryless nature of DIPV, rather than DIPV being a fixed set of practices with fixed effects. DIPV is extended, spatially and temporally, to not only the primary victim/survivor, but also colleagues, work communities, and data and other systems, with consequent physical, emotional, and organisational effects. Associated workplace dynamics are also likely to be intersectionally gendered, regarding, for example, DIPV disclosure, collegial reactions, and formal responses.

Ethical Challenges: The Development of Proactive Responses, Policy Processes and Practice

With all these challenging conditions, variations and impacts of DIPV, workplaces need to develop proactive strategic organisational policy guidelines and leadership on safe working environments, rather than relying on over-simplified, one-size-fits-all procedures. Addressing these issues raised can mean working towards wholesale organisational cultural change to violation-free organisations, with clear leadership and policy statements of zero-tolerance of violence, bullying, harassment and IPV, digital or not, and high levels of organisational trust that DIPV will be taken very seriously.

Arenas for policy development include: monitoring prevalence; preventive measures on DIPV, as in staff training and information-circulation, in line with pursuit of human dignity and safety from violence; protection of (potential) victim/survivors, for example, their data protection for those affected by DIPV, in keeping with privacy, human dignity and safety; disciplinary procedures and rehabilitation of perpetrators, as part of justice in dealing with DIPV; service provision for (potential) victim/survivors, that respects privacy and autonomy for victims, as well as for bystanders, colleagues and perpetrators; developing partnerships with stakeholders with relevant expertise; and overall policy and practice development, including ensuring management and supervision are well-informed on DIPV, and redressing intersectional gender power imbalances.Footnote 14 Regarding specific practices, Arnold (2014) proposes that the employer: speak with the employee about the incident as soon as possible; provide employee assistance materials to the victim; take steps to maintain the employee’s safety and limit the situation’s impact in the workplace; and work with IT to optimise online security.

While noting these specific examples, fixed blueprint policies for DIPV are likely to be less applicable than more open-ended contingent, monitored commitment to working against DIPV (as part of broad anti-violence commitments) and its unpredictable effects. As noted, much DIPV cannot be reduced to specific ‘incidents’ in one time and place. Thus, proactive ethical policy and practice are much more than the application of given rules. They necessitate the internalisation by employees, managers and stakeholders of anti-DIPV practice throughout, seeking to do no harm (non-maleficence) and protecting employee welfare (beneficence), with respect for persons; centring the person who experiences DIPV, damage control and support, minimising further harm, and fairness and justice for victim/survivors, and perpetrators.

Moreover, in light of the complexity and undecidability of the digital world, ongoing and changing experiences and knowledge of DIPV in and around the organisation need to be drawn upon in a democratic way, including in-house expertise of IT departments, external partnerships and experts, such as trade unions, professional associations, employers’ federations, lawyers, and activists. This includes keeping up-to-date on laws regarding hate speech, communication offences, online harms, and technological innovations, as these can all contribute to DIPV. Ethical policy and practice on DIPV are also needed in relation to specific organisational groupings, specifically: direct victim/survivors; perpetrators; colleagues of victim/survivors and/or perpetrators; supervisors, managers and board members; other stakeholders. We briefly consider these in turn.

Direct Victims/Survivors

In providing support, it is advisable to connect with established and expert victim support services, including those online. In terms of internal organisational process, informed consent for victim/survivors regarding pursuit of a legal case against a perpetrator of DIPV needs to be taken very seriously, as does the minimising, wherever possible stopping, of further DIPV, harm and invasion of privacy. While DIPV clearly has a host of negative effects, it is important to appreciate that employment and workplace relations can also be at times a means of surviving and coping with DIPV (Beecham, 2009, 2014), as well as providing potential pathways for leaving a violent partner (Patton, 2003; Rothman et al., 2007). In such processes, workplace colleagues and managers need to be supportive, both formally and informally, with care, compassion, and knowledge about the complexities and coercive, manipulative nature of (D)IPV.

Perpetrators

While there is undoubted value in a victimological approach to DIPV, it can inadvertently play down attention to perpetrators, even render perpetrators invisible. Workplace policies and practices to support victim/survivors may not acknowledge that, amongst employees, there may also be perpetrators. In dealing with (potential) perpetrators, many workplaces already have general disciplinary procedures, including formal warnings, that can be built upon regarding DIPV. Disciplinary procedures need to be reviewed to ensure they are suitable for DIPV, for example, keeping victims informed, restricting/preventing perpetrators’ access to workplace ICTs, and, if warranted, dismissal. Criminal and legal procedures may sometimes override workplace policy (Rackley et al., 2021).

Colleagues

Colleagues can be involved in a wide variety of ways, as indirect victims/survivors, as supporters of direct victims/survivors, reporters of others’ abuse, as bystanders, as colluding with perpetrators. DIPV can (directly or indirectly) involve multiple work colleagues, for example, as group experience of or collusion in humiliation, and individual victim/survivors can suffer multiple forms of DIPV, adding to power imbalances. More collective situations can interact in complex ways, with teamwork dynamics, as with collective trauma. Colleagues may be approached by the perpetrator to gather information or spread information about the victim. Being a colleague in these situations can have major effects, including reactivating earlier experiences of abuse, and decreased work capacity for entire teams and units, as noted earlier. This may raise novel demands on collegial relations and team dynamics, requiring more strategic intervention and support. These are matters to be addressed proactively in organisational policy and especially in training for supervisors and managers.

Supervisors, Managers, Board Members, Entrepreneurs and Owners

These groups have special responsibilities to deal with DIPV and its impacts, regarding specific occurrences of DIPV, in developing strategy, policy and culture, and in terms of businesses as legal entities. This includes being fully trained on the topic, being cognisant of intersectional gender power dynamics, including responding to gendered resistance to feminist practice on DIPV, and observing data protection. This responsibility is not an ‘add-on’ but part of the supervisory task. There is a need for better managerial understanding of distinctions, sometimes subtle, between consensual workplace intimate relationships and hierarchical misuse of power, leading to sexual hubris and sexploitation in the organisation, and then possibly DIPV during or after the supposed ‘romance’ (Mainiero, 2021). If DIPV is enacted by a supervisor or manager, further complex organisational power issues can be at play, with the crossing of boundaries between workplace hierarchy and more private spheres, including intimacy and potential or previous relationships, or reactions to rejection. Accountability and avoidance of conflicts of interest are clearly crucial for those involved in dealing with DIPV (Roofeh, 2021), as is a high level of moral expectation on managers (Ciulla & Donelson, 2011). Furthermore, managers themselves can be both victims and perpetrators of DIPV. This can be invisible in the organisation yet have serious consequences for the units they lead. Appropriate policy needs to be in place when such DIPV is alleged or demonstrated.

There are also sometimes complex inter-organisational and transnational responsibilities and relations for managers to deal with. DIPV operates across different societal contexts, (inter)national laws and legal provisions, including employment law. This can be a challenge for transnational corporations, across jurisdictions, whereby ethical policy and practice on DIPV may become a cross-border, inter-organisational concern, including engagement with international service providers. This prompts the question of the extent of organisational commitment to opposing DIPV (and other forms of violence) beyond organisational and even national boundaries, especially where corporate ethics are at odds with local or societal ethics.

As well as the overlapping reputational and financial implications of DIPV noted, if the abuse is perpetrated from an employee’s place of work or employer-issued devices, the organisation may be liable, depending on the jurisdiction, for employee’s actions (Ryan, 2016). Depending on the judicial context, plaintiffs could argue for the ethical and legal responsibility of businesses under the doctrine of respondeat superior whereby the organisation is responsible for their employees’ actions (Brazzano, 2020). Managers, IT and HR departments, and corporate legal teams need to ensure their organisation is adequately protected from such digital violence and abuse, whether IPV-related or not. This is especially challenging for employers operating transnationally in multiple jurisdictions (Hearn & Hall, 2021). Even if employer liability is not pursued, an employee being accused of such a crime may expose the employer to reputational damage or other unwelcome consequences (Brazzano, 2020).

Additionally, and importantly, some business sectors, most obviously ICT, technology, engineering, design, and social media sectors (Suzor et al., 2019), have further important responsibilities to counter DIPV proactively, as, for example, through ‘Coercive control resistant design’ (Nuttall et al., 2019), trauma-informed design principles, and working in further ways to decrease the extension of coercive control via technology (Kerremans et al., 2022). Such questions link to wider debates on the ethics and politics of platform society (van Dijck et al., 2018), platform capitalism (Srnicek, 2016) and surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019). To cite a leading media commentator just recently put it:

“The very fact that social media companies enjoy global accessibility should impose an added obligation on corporations to accept they are “publishers not just platforms”. Great as the technical problems may be, they must be held to account for the harm they can cause to others.” (Jenkins, 2022).

Other Stakeholders

Even though (external) stakeholders vary in their formal responsibility to address DIPV in specific workplaces, some, such as trade unions, do bear such a responsibility. These questions link to wider discussions on civil society stakeholders’ responsibilities and engagements. We might ask: should stakeholders have a responsibility towards business, and individuals within them, experiencing or affected by DIPV, employed or otherwise linked, and towards holding perpetrators of DIPV accountable? Such responsibilities reach beyond legal responsibility and connect with wider power dimensions in local/glocal communities, and prospects for corporate performance and social justice dependent on relations to stakeholders.

Finally, DIPV raises challenges in relation to existing policy arenas. Current HR policies rarely directly address DIPV; however, DIPV clearly impacts the well-being of employees, teams, and the wider organisation, including occupational health and safety. Narrow, monolithic views on well-being can lead to neglect of issues in private domains affect work life (Cronin de Chavez et al., 2005). DIPV may be usefully considered, transversally, alongside policies on, for example, well-being, health and safety, bullying and harassment, grievance procedures, sickness absence, stress and burnout, equality, inclusion and diversity, and respect/dignity at work. Policy and practice on DIPV need to be brought into conversation with such policy frames. Yet, formal policies alone can often have limited effects on well-being, or be partially implemented, as informal cultures and support from colleagues and leaders can be more significant for everyday work well-being. Unintended consequences of placing DIPV into existing occupational health or well-being framings, devised for other purposes, need to be considered. Put another way, is the violated person to be represented as a victim, survivor, employee in need of occupational support, colleague, supervisor, manager, and so on?

To sum up: recognising the complex phenomenon of DIPV, countering its negative impacts, and developing proactive policy and practice in and around workplaces, including creating healthy organisational cultures with zero-tolerance for abuse or misconduct, including DIPV, bring multiple ethical challenges for workplaces. They entail combining strong policy frameworks for safety, anti-violence and feminist ethics of care with responding to complexity, contextual variability, contingency, even elusiveness, of DIPV, and relationship-based ethics in everyday working life; balancing concern beyond organisational boundaries in working against DIPV, with respecting privacy and confidentiality; engaging with the sometime spacelessness and timelessness of DIPV; and furthering feminist ethical practice on DIPV in workplaces, whilst addressing intersectionally gendered power, allegiances and resistances in workplaces.

Concluding Discussion: Contributions and Future Research Agenda

We conclude with ways forward for future research on DIPV in and around workplaces, noting some contributions we have sought to make. First, we foreground the growing importance of research on the intersections of DIPV and the workplace, including on monitoring and evaluating prevalence of, and policy and practice on, DIPV across work sectors and locations, and on adoption of more proactive stances in workplace policy and practice in relation to DIPV, in their various forms and contexts. While there is much literature on DIPV itself, and IPV and workplaces, there is less about DIPV in relation to workplaces. We seek to contribute to this focus, in the face of current scattering of literature across disciplines. Reflective conceptual and theoretical development is needed in research, policy and practice on DIPV, with evolving technologies, and mergings of online and offline, so-called ‘onlife’ (Floridi, 2015).

Second, much of what we have discussed on DIPV is also relevant to, and may intra-act with, digital bullying, harassment, violence and abuse in the workplace more generally. However, a typical difference is the relationship between perpetrator and victim/survivor. With workplace bullying and harassment, the relationship tends to be ‘collegiate’ or organisationally-located, rather than (formerly) ‘intimate’, with an (ex-) partner. DIPV carries important further features compared with much workplace bullying and harassment, including: greater risk of serious injury and homicide; potential coercive control on victims’ lives; legacy of state reluctance to intervene in domestic/intimate relationships and recognise IPV as criminal; risks to children and family members (Bailey et al., 2021; Henry & Powell, 2018). The interrelations of workplace harassment, bullying and abuse, IPV and DIPV are key in the research agenda.

Third, there is the relation of ‘intimacy’ and violence in DIPV, and the contradictory process of publicisation (what becomes public), via digitalisation (see fn. 13). The very notions of IPV and DIPV carry the contradiction of ‘intimacy’ and violence: violence destroys intimacy, the intimacy of partnerships, and intimate partnerships. This contradiction is deepened when violence is digitalised, extended spatially/temporally, and moreover carried over towards workplaces. DIPV not only impacts on work; it can also be exerted on and within workplaces themselves, including spreading rumours, hacking work technology, disrupting data systems.

Fourth, research on DIPV in workplaces needs to examine intersectionally gendered dynamics across all processes, in perpetration, victimisation, impacts on colleagues, workplace responses, and interconnections with intersectionally gendered organisational structures and processes. This includes paying attention to how intersectionalities, such as of and between age, class, ethnicity, gender, racialisation, religion, and sexualities, impact on lived experiences of DIPV, and interpersonal and organisational responses, or indeed non-responses, to DIPV, both formal and informal.

Fifth, all these above points feed into the basic question of developing ethically responsible workplace responses, policy processes, and practice in relation to DIPV. Human dignity, safety, justice, privacy, autonomy, and balance of power are all clearly important, but there are further challenges not so easily specifiable. These ethical values are not only individual but also matters of workplace communality and collegiality, further complicated across different work sectors, for example, those that rely on high trust. These questions require further attention. A specific ethical challenge concerns the balance of managerial responsibilities towards DIPV and employer knowledge of personal, even sexual and intimate, lives of employees, whilst protecting personal privacy. A related ethical challenge is DIPV, in its various forms and permutations, can be indeterminate, undecidable, unspecifiable in advance, unpredictable, pervasive, elusive, blurring IRL/virtual. DIPV can occur at any moment, within, outside or in relation to work. These features raise complex ethical challenges for workplaces, complicated by such probable future tendencies as increased remote and transnational working, portfolio careers, and changing technologies. The changing nature of ICTs, DIPV and work contexts militate against simple, fixed solutions, and rather suggest the necessity of an evolving vigilance.

Finally, these ethical challenges apply both within and between businesses and workplaces. DIPV cannot be ignored by business, workplace, and organisational actors. This suggests an additional ethical commitment to opposing DIPV (and violence more generally) in its new, as yet not known, forms, and thus an openness to the very question of understanding what is and what may count as violence (Hearn et al., 2022). Businesses have an ethical responsibility, beyond legal responsibility, reputational interests, and their immediate boundaries, as part of the ongoing process of reducing and stopping violence, IPV and DIPV.

Data availability

Not applicable

Notes

Debates on intersectionality and gender are vast and wide-ranging. Collins and Bilge’s (2016) overview book, Intersectionality, analyses “the complexities of intersectionality” (p. viii), foregrounding relationality, social context, power, inequality, social justice, and critical praxis. For current purposes, by ‘intersectionally gendered’ we refer to how different systems of oppression—such as capitalism, racism, and heteronormativity—intersect with gender to impact how IPV and DIPV are perpetrated, experienced, and responded to (Crenshaw, 2017).

We use the term, ‘victim/survivor’, to recognise both victimhood and survivorhood, without placing those who experience (D)IPV as solely (non-agentic) victims or solely (agentic) survivors. Victim/survivors might wish to represent themselves in different ways, not only in such terms. Tragically, not all who experience (D)IPV survive (Boyle & Rogers, 2020; Kelly et al., 1996). IPV is more precise than ‘domestic violence’, that is not always ‘within the home’, and ‘family violence’, that may obscure responsibility, and includes relationships other than those between partners. Additionally, the term, ‘partner’, within IPV, has been problematised, as meaning more than a current sexual or romantic partner or spouse. ‘Partner’ includes ex-partners, and in some cases situations where one person defines themselves as a partner, while the other does not. Understandings of such relationships, for example, what is meant by ‘hanging out’, vary by local and generational contexts. Violence involving other family, intimate and friendship relations sometimes raises related challenges.

DIPV is equivalent to ‘cyber intimate partner victimisation’ (Fernet et al., 2019) and ‘digital coercive control’ within IPV (Harris & Woodlock, 2019). Many other terminologies are used (Hall et al., 2022), each with different emphases, for example, ‘technologically-facilitated sexual violence’ and ‘technology-facilitated IPV’, that may overlap with DIPV. We are cautious about the suffix, ‘facilitated’, as that can take away some agentic responsibility from perpetrators (Vera-Gray, 2017).

From here on, we use ‘businesses’, ‘employing organisations’ and ‘workplaces’ interchangeably to refer to all kinds of economic activity including private (corporate, SME, self-employment), public and third sectors.

Estimates of those experiencing IPV in the past year vary from 15 to 20% or 1 in 4 women and 1 in 6 men (Crime Survey …, 2019; ONS, 2019; Sardinha et al., 2022; WHO, 2013). KPMG’s (2019) research estimated approximately 15% of the female workforce in Germany, India, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, and the UK had experienced IPV in the previous year, with 88% of victims/survivors suggesting IPV impacted their career progression or earnings.

In working against violence, it is politically important to acknowledge earlier feminist work in the field, as well as to avoid academic ageism (Hearn & Parkin, 2021).

Swanberg and Logan (2005) refer to perpetrators’ ‘job interference tactics’ before, during and after work, reducing women’s job performance. A UK Trades Union Congress (2014) survey (n = 3423) found that of respondents who had experienced IPV, nearly half had been prevented getting to work, due to being injured or restrained by their perpetrator; one in ten experienced IPV in their workplace (predominantly abusive emails and telephoning); 86% thought their performance and attendance had been negatively affected through being tired, distracted, or unwell; some had lost their job. In Canadian research (n = 8423) on ‘domestic violence’ and the workplace (Wathen et al., 2015), 37% of victims reported that their experiences of IPV impacted on co-workers, mostly in terms of stress or concern about the situation.

Written evidence (OSB0097) from Glitch, the UK charity to end online abuse, to the UK Parliamentary report on Draft Online Safety Bill (2021, p. 13).

Our reference to ‘gender and violence’ includes: VAWG, GBV, DV, IPV, IBSA, abuse against feminists.

One way of furthering feminist ethical practice on DIPV and workplaces that may be productive in future work is in terms of feminist ethics of care, that is: caring about; taking care of; giving care; receiving care; caring with (Tronto, 2013). While the place of feminist ethics in feminist theory is heavily contested, we see feminist ethics as intertwined with feminist politics (see Norlock, 2019; Wilén, 2021).

Differential constructions of time around DIPV are important here, as in the contrast between work time, organisational time, and phenomenological time, as well as, say, project time and biographical time. ‘Chrononormativity’, the “use of time to organize individual human bodies for maximum productivity” (Freeman, 2010, p. 3; see Riach et al., 2014), and clock-time organisation of life in which speed, future projection and linearity are valorised, and individuals are regulated (Pickard, 2016), are at odds with forms of time likely to be experienced with DIPV in and around workplaces.

In some countries, for example, Finland, employers have a legal responsibility to offer rehabilitation for employees with alcohol-related problems.

References

Acker, J. (2006). Inequality regimes: Gender, class, and race in organizations. Gender & Society, 20(4), 441–464.

Adhia, A., Gelaye, B., Friedman, L. E., Marlow, L. Y., Mercy, J. A., & Williams, M. A. (2019). Workplace interventions for intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 34(3), 149–166.

Ågotnes, K. W., Einarsen, S. V., Hetland, J., & Skogstad, A. (2018). The moderating effect of laissez-faire leadership on the relationship between co-worker conflicts and new cases of workplace bullying. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(4), 555–568.

Akrich, M., & Latour, B. (1992). A Summary of a convenient vocabulary for the semiotics of human and nonhuman assemblies. In W. E. Bijker & J. Law (Eds.), Shaping technology/building society (pp. 259–264). MIT Press.

Al-Alosi, H. (2017). Cyber-violence: Digital abuse in the context of domestic violence. University of New South Wales Law Journal, 40(4), 1573–1603.

Arnold, M. (2014). A disturbing picture: Revenge porn is a vicious new way to smear someone’s professional reputation. HR Magazine (Society for Human Resource Management). Retrieved July 21, 2014, from https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/Pages/0814-revenge-porn.aspx

Bailey, J., Flynn, A., & Henry, N. (Eds.). (2021). The Emerald international handbook of technology-facilitated violence and abuse. Emerald.

Baird, S., & Jenkins, S. R. (2003). Vicarious traumatization secondary traumatic stress and burnout in sexual assault and domestic violence agency staff. Violence and Victims, 18(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2003.18.1.71

Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. SIGNS: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801–831.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

Barter, C., & Koulu, S. (2021). Special issue: Digital technologies and gender-based violence—mechanisms for oppression, activism and recovery. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 5(3), 367–375.

Beecham, D. (2009). The impact of intimate partner abuse on women’s experiences of the workplace: A qualitative study. Warwick University.

Beecham, D. (2014). An exploration of the role of employment as a coping resource for women experiencing intimate partner abuse. Violence and Victims, 29(4), 594–606.

Bennett, T., Wibberley, G., & Jones, C. (2019). The legal, moral and business implications of domestic abuse and its impact in the workplace. Industrial Law Journal, 48(1), 137–142.

Boyle, K. M., & Rogers, K. B. (2020). Beyond the rape “victim”–“survivor” binary: How race, gender, and identity processes interact to shape distress. Sociological Forum, 35(2), 323–345.

Brantner, C., Rodriguez-Amat, J. R., & Belinskaya, Y. (2021). Structures of the public sphere: Contested spaces as assembled interfaces. Media and Communication, 9(2), 16–27.

Brazzano, R. (2020). Zoombombing, sexting and revenge porn, oh my! New York Law Journal. Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.law.com/newyorklawjournal/2020/06/10/zoombombing-sexting-and-revenge-porn-oh-my/?slreturn=20200702090539

Ciulla, J., & Donelson, R. (2011). Leadership ethics. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 229–241). Sage.

Cockburn, C. (2004). The continuum of violence: A gender perspective on war and peace. In W. Giles & J. Hyndman (Eds.), Sites of violence: Gender and conflict zones (pp. 24–44). University of California Press.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (2017). On violence, intersectionality and transversal politics. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(9), 1460–1473.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity.

Coole, D., & Frost, S. (Eds.). (2010). New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics. Duke University Press.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

Cronin de Chavez, A., Backett-Milburn, K., Parry, O., & Platt, S. (2005). Understanding and researching wellbeing. Health Education Journal, 64(1), 70–87.

Crime Survey for England and Wales. (2019). Domestic abuse in England and Wales overview. Retrieved November, 2019, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domesticabuseinenglandandwalesoverview/november2019

Crouter, A. C. (1984). Spillover from family to work: The neglected side of the work-family interface. Human Relations, 37(6), 425–441.

Crowe, M. (2016). ‘55,000 people have seen me naked’: A story of ‘revenge porn’ and the lawyers who are trying to stop it. Puget Sound Business Journal. Retrieved August 5, 2016, from https://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/blog/techflash/2016/08/55-000-people-have-seen-me-naked-a-story-of.html

Douglas, H. (2017). Legal systems abuse and coercive control. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(1), 84–99.

Douglas, H., Harris, B. A., & Dragiewicz, M. (2019). Technology-facilitated domestic and family violence: Women’s experiences. The British Journal of Criminology, 59(3), 551–570.

Draft Online Safety Bill (2021). London: House of commons and house of lords. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8206/documents/84092/default/

Dragiewicz, M., Burgess, J., Matamoros-Fernández, A., Salter, M., Suzor, N. P., Woodlock, D., & Harris, B. (2018). Technology facilitated coercive control: Domestic violence and the competing roles of digital media platforms. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 609–625.

Duerksen, K. N., & Woodin, E. M. (2019). Technological intimate partner violence : Exploring technology-related perpetration factors and overlap with in-person intimate partner violence. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 223–231.

EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). (2014a). Violence against women: An EU wide survey—main results report.

EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). (2014b). Violence against women: An EU wide survey—survey methodology, sample and fieldwork.

Evans, M. L., Lindauer, M., & Farrell, M. E. (2020). A pandemic within a pandemic—intimate partner violence during Covid-19. The New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2024046

Fernet, M., Lapierre, A., Hebert, M., & Cousineau, M. M. (2019). A systematic review of literature on cyber intimate partner victimization in adolescent girls and women. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.06.005

Floridi, L. (Ed.). (2015). The onlife manifesto: Being human in a hyperconnected era. Springer.

Freed, D., Palmer, J., Minchala, D., Levy, K., Ristenpart, T., & Dell, N. (2017). Digital technologies and intimate partner violence: A qualitative analysis with multiple stakeholders. Proceedings ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 1, 46. https://doi.org/10.1145/3134681

Freed, D., Palmer, J., Minchala, D., Levy, K., Ristenpart, T., & Dell, N. (2018). “A stalker’s paradise”: How intimate partner abusers exploit technology. Proceedings, 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (p. 13). ACM.

Freed, D., Havron, S., Tseng, E., Gallardo, A., Chatterjee, R., Ristenpart, T., & Dell, N. (2019). “Is my phone hacked?” Analyzing clinical computer security interventions with survivors of intimate partner violence. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3, 202. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359304

Freeman, E. (2010). Time binds: Queer temporalities, queer histories. Duke University Press.

Gámez-Guadix, M., Borrajo, E., & Calvete, E. (2018). Partner abuse, control and violence through internet and smartphones. Papeles Del Psicólogo, 39(3), 218–227.

Gangoli, G., Bates, L., & Hester, M. (2019). What does justice mean to black and minority ethnic (BME) victims/survivors of gender-based violence? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(15), 3119–3135.

Giesbrecht, C. J. (2022). Toward an effective workplace response to intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(3–4), 1158–1178.

Hadley, L. (2017). Tackling domestic abuse in a digital age: A recommendations report on online abuse by the all-party parliamentary group on domestic violence. Women’s Aid Federation of England.

Haggerty, K. D., & Ericsson, R. V. (2000). The surveillant assemblage. British Journal of Sociology, 51(4), 605–622.

Hall, M., & Hearn, J. (2017). Revenge pornography: Gender, sexualities and motivations. Routledge.

Hall, M., & Hearn, J. (2019). Revenge pornography and manhood acts: A discourse analysis of perpetrators’ accounts. Journal of Gender Studies, 28(2), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1417117

Hall, M., Hearn, J., & Lewis, R. (2022). Digital gender-sexual violations: Violence, technologies, motivations. Routledge.

Hanmer, J. (1998). Out of control: Men, violence and family life. In J. Popay, J. Hearn, & J. Edwards (Eds.), Men, gender divisions and welfare (pp. 128–146). Routledge.

Hanmer, J., & Maynard, M. (Eds.). (1987). Women, violence and social control. Macmillan.

Haraway, D. (1992). The promises of monsters: A regenerative politics for inappropriate/d Others. In L. Grossberg, C. Nelson, & P. Treichler (Eds.), Cultural studies (pp. 295–337). Routledge.

Harris, B. A., & Woodlock, D. (2019). Digital coercive control: Insights from two landmark domestic violence studies. British Journal of Criminology, 59(3), 530–550.

Health and Safety Executive. (2020). Work-related stress, anxiety or depression statistics in Great Britain. HSE.

Hearn, J. (1992). Men in the public eye. Routledge.

Hearn, J. (1998). The violences of men. Sage.

Hearn, J. (2014a). Men, masculinities and the material(-)discursive. NORMA: The International Journal for Masculinity Studies, 9(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2014.892281

Hearn, J. (2014b). Sexualities, organizations and organization sexualities: Future scenarios and the impact of socio-technologies (A transnational perspective from the global “North”). Organization: The Critical Journal of Organization, Theory and Society, 21(3), 400–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413519764

Hearn, J., & Hall, M. (2021). The transnationalization of online sexual violation: The case of “revenge pornography” as a theoretical and political problematic. In Y. R. Zhou, C. Sinding & D. Goellnicht (eds.), Sexualities, transnationalism, and globalization: New perspectives (pp. 92–106). Routledge.

Hearn, J., & Parkin, W. (1983). Gender and organisations: A selective review and a critique of a neglected area. Organization Studies, 4(3), 219–242.

Hearn, J., & Parkin, W. (2001). Gender, sexuality and violence in organizations. Sage.

Hearn, J., & Parkin, W. (2021). Age at work: Ambiguous boundaries of organizations, organizing and ageing. Sage.

Hearn, J., Strid, S., Humbert, A. L., Balkmar, D., & Delaunay, M. (2022). From gender regimes to violence regimes: Re-thinking the position of violence. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 29(2), 682-705.

Henry, N., & Powell, A. (2018). Technology-facilitated sexual violence: A literature review of empirical research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(2), 195–208.

Henry, N., Powell, A., & Flynn, A. (2017). Not just ‘revenge pornography’: Australians’ experiences of image-based abuse. A summary report. RMIT University.

Henry, N., Flynn, A., & Powell, A. (2020). Technology-facilitated domestic and sexual violence: A review. Violence against Women, 26(15–16), 1828–1854.

Hird, M. (2004). Feminist matters: New materialist considerations of sexual difference. Feminist Theory, 5(2), 223–232.

Hochschild, A. R. (1997). The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work. Metropolitan.

Human Rights Watch. (2020). Women face rising risk of violence during Covid-19. HRW.

Humbert, A., Strid, S., Hearn, J., & Balkmar, D. (2021). Undoing the ‘Nordic Paradox’: Factors affecting rates of disclosed violence against women across the EU. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249693

Jane, E. (2016). Misogyny online: A short (and brutish) history. Sage.

Jenkins, S. (2022). Do you want free speech to thrive? Then it has to be regulated, now more than ever. The Guardian.

Johnson, D. G. (2015). Technology with no human responsibility? Journal of Business Ethics, 127(4), 707–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2180-1

Kelly, L. (1988). Surviving sexual violence. Polity.

Kelly, L., Burton, S., & Regan, L. (1996). Beyond victim or survivor: Sexual violence, identity and feminist theory and practice. In L. Adkins & V. Merchant (Eds.), Sexualizing the social (pp. 77–101). Palgrave Macmillan.

Kerrbach, O., & Mignonac, K. (2006). How organisational image affects employee attitudes. Human Resources Management Journal, 14(4), 76–88.

Kerremans, A., Wuiame, N., & Denis, A. (2022). RESISTIRE factsheet: Creating safe digital spaces. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7035486

KPMG (2019). The workplace impacts of domestic violence and abuse: A KPMG report for Vodafone Group. Retrieved July 4, 2019, from https://www.vodafone.com/content/dam/vodcom/images/homepage/kpmg_report_workplace_impacts_of_domestic_violence_and_abuse.pdf

Langlois, G., & Slane, A. (2017). Economies of reputation: The case of revenge porn. Communication and Critical/cultural Studies, 14(2), 120–138.

Lassiter, B. J., Bostain, N. S., & Lentz, C. (2021). Best practices for early bystander intervention training on workplace intimate partner violence and workplace bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11–12), 5813–5837.

Lenhart, A., Ybarra, M., Zickuhr, K., & Price-Feeney, M. (2016). Online harassment, digital abuse, and cyberstalking in America. Data Society.

Lewis, R. (2004). Making justice work: Effective interventions for domestic violence. British Journal of Criminology, 44(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/44.2.204

Lichter, S. (2013). Unwanted exposure: Civil and criminal liability for revenge porn hosts and posters. JOLT Digest: Harvard Journal of Law and Technology. Retrieved May 27, 2013, from http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/digest/privacy/unwanted-exposure-civil-and-criminal-liability-for-revenge-porn-hosts-and-posters

Lykke, N. (2020). Transversal dialogues on intersectionality, socialist feminism and epistemologies of ignorance. NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 28(3), 197–210.

Mackay, F. (2015). Radical feminism: Feminist activism in movement. Palgrave Macmillan.

MacKinnon, C. A. (1993). Only words. Harvard University Press.

MacQuarrie, B., Scott, K., Lim, D., Olszowy, L., Saxton, M. D., & MacGregor, J. (2019). Understanding domestic violence as a workplace problem. In R. J. Burke & A. M. Richardsen (Eds.), Increasing occupational health and safety in workplaces: Individual, work and organizational factors (pp. 93–114). Edward Elgar.

McGlynn, C., & Rackley, E. (2017). Image-based sexual abuse. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 37(3), 534–561.

McGlynn, C., & Westmarland, N. (2019). Kaleidoscopic justice: Sexual violence and victim-survivors’ perceptions of justice. Social & Legal Studies, 28(2), 179–201.

Maddocks, S. (2020). ‘A deepfake porn plot intended to silence me’: Exploring continuities between pornographic and ‘political’ deep fakes. Porn Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2020.1757499

Mainiero, L. (2021). Workplace romance versus sexual harassment: A call to action regarding sexual hubris and sexploitation in the #MeToo era. Gender in Management, 35(4), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-11-2019-0198

Marganski, A., & Melander, L. (2018). Intimate partner violence victimization in the cyber and real world: Examining the extent of cyber aggression experiences and its association with in-person dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(7), 1071–1095.