Abstract

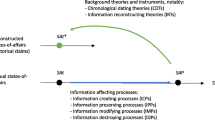

One task of historians is to construct causal ascription of singular historicals between eminent historical events. For instance, the controversy resulting from the confusing butterfly ballot of Florida’s year 2000 presidential election cost Gore his presidency. However, to research into these matters is inevitably to appeal to counterfactual deliberation in an epistemic fashion because the past is fixed. One standard idea is Max Weber’s, Weber causation: “f was a cause of φ” is assertable iff “¬f □→ ¬φ” is assertable. Reiss (2009) gives an exceptionally good analysis of this topic and outlines historians’ reasoning, claiming that backtracking analyses of counterfactual conditionals employed in historical thought experiments is the signature of historical study of causal ascription of singular historicals. Nevertheless, he concludes that it is very difficult to reach an uncontroversial ascription for this sort in most cases. For this reason, he proposes to find difference-making relations that will suffice. The objective of this paper is to provide a more fine-grained, intervention-based, backtracking analysis of counterfactual conditionals upon which a more satisfactory account of causal ascription of singular historicals can be given. Reiss’ account of difference-making relation will be shown to be unsatisfactory. Moreover, a formal ground of the epistemology of historical thought experiments can be given, along with the constraints of this account resultant from the semantic features of non-transitivity and strong centering of counterfactual conditionals. Finally, some epistemological points of causal ascription of singular historicals and historical thought experiments will be given.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While this is correct in many cases of causal ascription, it is not so in every case. The complication will be discussed further in the third and fourth sections.

For instance, Daniel Nolan, “Why historians (and everyone else) should care about counterfactuals” (Philosophical Studies (2013) 163:317–335).

For a more detailed discussion, please see the fourth section.

Employing counterfactual conditionals means this account has to inherit the semantic features of non-transitivity and strong-centring. The fifth section will be explained why the proposed account is compatible with them.

Except truth normativity, all other accounts of assertion normativity are about different epistemic features of the normativity of assertion making. For truth normativity, its secondary propriety account is about subjective epistemic feature as well.

Strictly speaking, this is not a ceteris paribus condition. The reason is clearly that backtracking analysis of relevant counterfactual conditional(s) of a given CASH is by default to backtrack to the precondition of the counterfactual antecedent, and if necessary to backtrack further. The process of backtracking is limited but not so limited to just amending the antecedent or its precondition.

Some may disapprove of the idea of a counterfact, holding it to be nonsense. Since it is a terminology issue and thus inessential to the points and arguments presented below, please find your own suitable idea or term(s).

Some may propose that, different from logical consistency, historical consistency comes in degrees. After all, it seems to make sense to say that the target counterfact is consistent with the actual course of history to some degree. However, I hold historical consistency to be a property that a counterfact is either with or without. What comes in degree is the likelihood for it to obtain and the quality of evidential support, but not historical consistency. Within the same evaluation context, even saying that the counterfact of one hypothesis is more historically consistent than that of the other is just loose talk. What one says is still that one counterfact is more likely to obtain than the other, or that the quality of evidential support is better.

I do believe causal model semantics is the right semantics for historical thought experiments and historical backtracking analysis. However, due to the constraint of this paper, this is left to further research.

The relevant historical pondering, but not the philosophical part, all comes from either Reiss or Khong, or both at times. This will not be further noted.

Obviously, with the insertion of the counterfact of the hawkish cabinet the explanation of why the rearmament is insufficient is more sensible. Since in the actual course of history it is a fact that there were hawkish cabinet members and it is also a fact that the rearmament was insufficient, whether the likelihood of the counterfact of the sufficient rearmament is well evidentially supported by the existence of hawkish cabinet members is less clear.

The same abbreviation, say, HCM, that is not in boldface means that it is a historical fact.

This view certainly has to be based on historical judgements of some qualified historians. As mentioned above, the reasoning here is assumed for the sake of simplicity. Or otherwise the claim that HCM is an anchoring fact is barely sensible.

The discussion of a given Weber causation, such as (WC)CH, mainly focuses on how to justify the assertability of the respective counterfactual conditional, such as (CH). For the sake of simplicity, the talk of assertability is often omitted, but the point is the same.

For further discussion, please see the following two sections.

We discussed this more thoroughly in Wang and Hou (2014).

We do not have to get into the semantics here. At least this second reading is pragmatically acceptable.

More discussions are in Wang and Hou (2014). Underpinning these discussions is the idea of causal model semantics, but strictly speaking, the presentation here is not and need not be causal modelling. Causal model semantics may contribute to the clarification of historical thought experiments and CASHs, which is worthy of further research, but the whole idea here is that the simpler current account already sufficed to do this job.

Another way to understand (CG3), it may seem to someone, is to take that ¬HC and that ¬RS to be some sort of compound cause of that ACH. This is not the case. Setting aside the above discussion of n-backtracking, what is crucial to the obtaining of that ACH is that ¬HC. If we remove that ¬HC from the causal graph, since it is also the cause of that ¬RS, it is gone too. Hence, that ACH does not obtain. Comparatively, if we remove that ¬RS from the causal graph, the causal connection from that ¬HC to that ACH is intact. So causal-wise, only that ¬HC matters.

This example comes from Victor Davis Hanson, “A Stillborn West? Themistocles at Salamis, 480 BC” (in Philip Tetlock, Richard Ned Lebow, and Geoffrey Parker (eds.), Unmaking the West: “What-If?” Scenarios That Rewrite World History (2006). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 47–89).

The conditionals are abbreviated as follows: had Chamberlain adopted anti-appeasement policy (AACH), Hitler would have backed down (BH), had the rearmament been sufficed (RS), Chamberlain would have adopted anti-appeasement policy (AACH), and had the cabinet been hawkish (HC), the rearmament would have been sufficed (RS).

The basic idea of that c causes e rests on a chain of stepwise influence from c to e. And by ‘a chain of stepwise influence’, it is saying that a range of c1, c2 … of different not-too-distant alterations of c (including the actual alteration of c) and a range of e1, e2 … of different not-too-distant alterations of e are such that, if c1 had occurred, e1 would have occurred, and if c2 had occurred, e2 would have occurred, and so on. Even if it is successful, it does not affect the above point.

The oddity of the account of CASH may be eased if it is reconstrued as a verbal dispute. It is granted that, given (CG1)/(BS1), that ¬RS had causal influence on that ¬BH except that it is not a cause of it according to the backtracking feature of CASH. Reiss’ account of CASHs has this same characteristic. As mentioned above, the entire project of backtracking analyses is and has to be epistemic. Non-transitivity of counterfactual conditionals and i-backtracking analyses of historical counterfactuals ascertain that the project not be about virtue history. Metaphysically speaking, there is a parallel similarity: although in a sense A is a cause of C because A is the cause of B and B is the cause of C, the causal effectiveness of B on C and of A on C is different. Furthermore, the peculiarity of the present account of CASHs is to decline that ¬RS is a cause of ¬BH in the given case because there is no other sensible way to analyse CASHs but to implement backtracking analyses of historical counterfactuals.

A rough but possible way, for instance, is to use a definite description instead to characterise the position that is germane to the occurrence of the target historical event. When such a CASH is established, the definite description can be replaced with the co-referential proper name who actually occupies the causal contributing position.

References

Khong, Yuen Foong (1996). Confronting Hitler and Its Consequences, in Philip Tetlock and Aaron Belkin 1996: 95–118.

Lewis, D. (1973). Causation. Journal of Philosophy, 70(8), 556–567.

Lewis, D. (1979). Counterfactual dependence and Time’s arrow. Noûs, 13(4), 455–476.

Lewis, D. (2000). Causation as influence. Journal of Philosophy, 97, 182–197.

Reiss, J. (2009). Counterfactuals, thought experiments, and singular causal analysis in history. Philosophy of Science, 76, 712–723.

Tetlock, Philip, and Belkin, Aaron (1996) Counterfactual thought experiments in world politics: logical, methodological, and psychological perspectives. In Tetlock and Belkin eds. (1996), Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics: Logical, Methodological and Psychological Perspectives. Princeton: Princeton University Press: 1–38.

Wang, L., and Hou, R. W. T. (2014). Conditionals and deliberations. Manuscript.

Weber, Max ([1905] 1949), “Objective Possibility and Adequate Causation in Historical Explanation”, in The Methodology of the Social Sciences. Edited and translated by Edward Shils and Henry Finch. Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 164–188. Originally published in Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik.

Woodward, J. (2011). Mechanisms revisited. Synthese, 183, 409–427.

Woodward, J., & Hitchcock, C. (2003). Explanatory generalizations, part I: A counterfactual account. Noûs, 37, 1–24.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was supported by research grant of Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan ROC (105-2410-H-194 -065-, 106-2410-H-194 -086 -MY2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, R.W.T. Backtracking Analysis and Causal Ascription of Singular Historicals. Philosophia 48, 1447–1467 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-020-00173-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-020-00173-x