Abstract

Companies are increasingly engaging in corporate activism, defined as taking a public stance on controversial sociopolitical issues. Whereas prior research focuses on consumers’ brand perceptions, attitudes, and purchase behavior, we identify a novel consumer response to activism, unethical consumer behavior. Unethical behavior, such as lying or cheating a company, is prevalent and costly. Across five studies, we show that the effect of corporate activism on unethical behavior is moderated by consumers’ political ideology and mediated by desire for punishment. When the company’s activism stand is [incongruent/congruent] with the consumer’s political ideology, consumers experience [increased/decreased] desire to punish the company, thereby [increasing/decreasing] unethical behavior toward the company. More importantly, we identify two moderators of this process. The effect is attenuated when the company’s current stance is inconsistent with its political reputation and when the immorality of the unethical behavior is high.

Similar content being viewed by others

In the past decade, more and more companies have engaged in corporate activism, defined as taking a public stance on controversial sociopolitical issues (Bhagwat et al., 2020, p. 1). For example, in April 2021, in response to potentially discriminatory voting rights bills proposed in several US states, many companies took a public stand against such legislation. In a two-page advertisement that appeared in major US newspapers, many companies including American Airlines and Under Armour defended the right of all eligible voters to have a fair and equal opportunity to cast a vote (Timm, 2021). Furthermore, consumers are demanding that companies take a stand on value-related issues. In a survey by Edelman (2022), 58% of consumers indicated that they bought or advocated for brands that shared their beliefs and values.

Prior research on the effect of corporate activism on consumer response focused on consumers’ brand perceptions and attitude (Garg & Saluja, 2022; Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020); mentions of buycotting or boycotting the brand on social media platforms (Liaukonytė et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022); and purchase intentions or brand choice (Hydock et al., 2020; Jungblut & Johnen, 2022). All of these are consumer behaviors that do not violate generally accepted moral principles. In this paper, we examine the effect of corporate activism on unethical consumer behavior toward the company. We define unethical behaviors as those that violate generally accepted moral norms and principles (e.g., Reynolds & Ceranic, 2007) including lying, cheating, and stealing. In deciding to behave unethically, consumers must trade off a desire to see themselves as moral against the benefits they accrue from dishonesty (e.g., financial rewards) (Mazar et al., 2008). This trade-off is effortful; for instance, lying often requires considerable cognitive effort (Anthony & Cowley 2012). Therefore, different psychological processes may underlie how consumers respond to behaviors that violate or do not violate moral principles.

Unethical consumer behavior is important to study because it is prevalent and costly to companies. Consumers may engage in wardrobing (i.e., returning used clothing), stealing towels from a hotel room, and lying to qualify for a promotion. For example, return fraud accounted for 10.4% of all returns, half of which were due to wardrobing (National Retail Federation, 2022). Shoplifting by ordinary consumers accounted for over $16 billion in Europe and the US in 2019 (Centre for Retail Research, 2020). Moreover, in the last few years, there are increasing reports of consumers behaving unethically, such as assaulting flight attendants (Baskas, 2023) or engaging in a flash robbery of a retail store (Falk, 2023). Depending on the company’s stand on a socio-political issue, hotel customers may be more or less likely to steal towels; customers of amusement parks may be more or less likely to lie about their child’s age to get a discount; and retail store customers may be more or less likely to engage in wardrobing. Thus, investigating whether corporate activism can accentuate or mitigate unethical behavior is important from both theoretical and practical perspectives.

In this research, we examine consumers’ unethical behavior towards companies engaged in corporate activism. Consistent with prior literature (e.g., Garg & Saluja, 2022), we investigate the moderating role of political ideology. Political ideology refers to the extent to which consumers see themselves as conservative or liberal (Jung & Mittal, 2020). As in the prior work on corporate activism, we propose that when the company’s stance is incongruent with a consumer’s political ideology, unethical behavior will increase. When the stance is congruent, however, unethical behavior will decrease. Contrary to prior literature, however, we propose a different mechanism to explain this effect: desire for punishment. Prior literature shows that the effect of activism on brand attitudes or brand choice is mediated by brand identification (Hydock et al., 2020; Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020) or positive, but not negative, emotions (Garg & Saluja, 2022). However, consumers are likely to engage in unethical behavior when they are angry with a company, and anger leads to the desire to punish (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008). Because corporate activism involves controversial sociopolitical issues that are likely to push consumers’ hot buttons and trigger anger, we propose that the desire for punishment will mediate the effect of activism on unethical behavior.

Another contribution of our work is to identify two moderators that attenuate the effects of corporate activism on unethical behavior: (1) the consistency between the company’s stance and its political reputation (hereafter, stance consistency) and (2) the immorality of the unethical behavior. Building on the desire for punishment mechanism, the first moderator attenuates the link between corporate activism and desire for punishment. When a company’s stance on a specific issue is inconsistent with the company’s political reputation, the proposed effect of corporate activism on desire for punishment and unethical behavior will be attenuated. The second moderator attenuates the link between desire for punishment and unethical behavior, such that the effect of corporate activism on unethical behavior will be mitigated when unethical behavior is perceived as highly immoral despite a desire to punish the company.

This research contributes to the literature on corporate activism and unethical behavior by investigating a novel but important consumer response to activism, unethical consumer behavior. Our findings suggest that corporate activism can motivate consumers to engage in unethical behaviors that are more effortful and sacrifice their moral values to punish the company. Moreover, unlike prior work that examines the mediating effects of identification with the brand (Hydock et al., 2020) and positive emotions (Garg & Saluja, 2022), we identify desire for punishment as a mediator. We rule out brand attitudes and perceptions of company harmfulness as alternative explanations, suggesting that engaging in unethical behavior may require a stronger motivation such as desire for punishment than attitudes and perceptions. Finally, we demonstrate boundary conditions for our effect by positing two novel moderators.

Conceptual Background

Corporate Activism

Much of the research that has examined consumer responses to corporate activism has focused on consumers’ brand perceptions and attitude (Garg & Saluja, 2022; Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020); social media behavior such as mention of the boycott/buycott and following/unfollowing a brand (Liaukonytė et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022); and purchase intentions or brand choice (Hydock et al., 2020; Jungblut & Johnen, 2022). Most research finds that engaging in corporate activism increases (decreases) consumers’ brand attitude and purchase intention when the company’s stance is congruent (not congruent) with their own (e.g., Hydock et al., 2020). Overall, the negative effect of incongruent activism on brand attitude and purchase intention is larger than the positive effect of congruent activism (Hydock et al., 2020; Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020). For instance, Mukherjee and Althuizen (2020) find only negative effects of incongruent corporate activism on brand attitude, but no positive effects of congruent activism. This negative effect can be attenuated when a brand’s market share is lower (Hydock et al., 2020) or when a larger number of companies take a stand on an issue during a similar period (Klostermann et al., 2021).

In this research, we propose unethical consumer behavior as a new consumer response to corporate activism. We note that although prior literature demonstrated the effects of activism on brand attitude and purchase behavior, it is not entirely clear whether activism would influence unethical consumer behavior because unethical behavior requires significant effort on the part of actors. Deciding whether to act unethically presents consumers with a conflict between a desire to see themselves as moral and the benefits they accrue from unethical behavior (Mazar et al., 2008). Lying also requires considerable cognitive effort because people who lie should maintain consistency of the information (Anthony & Colwy, 2012).

Examining consumer responses to corporate activism beyond brand purchase and choice is also important from a practical point of view because consumers often cannot change their purchase behavior (i.e., boycott a brand) due to high switching costs. For example, using quantitative modeling, Liaukonytė et al. (2023) demonstrated that after the CEO of Goya praised then president Donald Trump, sales increased by 22% although negative social media posts dominated. While buycotting by Republicans was one reason for the increase, the authors showed that another reason was that many existing Goya customers continued purchasing Goya products due to high switching costs and brand loyalty. In the absence of the ability to switch to a different brand, consumers may engage in unethical behaviors toward the company.

Unethical Behavior

Prior literature has documented various factors that influence unethical behavior. These include situational factors such as self-control depletion and type of reward (cash vs. token) (Gino et al., 2011; Mazar et al., 2008). Since unethical behavior is a social interaction of two entities (the actor/perpetrator and the target/victim), researchers have also identified several factors pertaining to actors and targets that may affect unethical behavior. Characteristics of the actor include moral identity and creativity (Gino & Ariely, 2012; Reynolds & Ceranic, 2007). Characteristics of the target, especially when the target is a company or an organization, include company size, perceived harmfulness of the company, and the consumer-company relationship (Rotman et al., 2018; Wirtz & McColl-Kennedy, 2010).

More relevant to our research, prior work has examined how a company’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) can influence unethical behavior against the focal company. List and Momeni (2021) found that CSR increased employees’ unethical behavior against the company. Learning that their company donated to a charity resulted in moral licensing, giving employees moral credit to cheat the company without hurting their positive self-image. CSR, which refers to “company actions that advance social good beyond that which is required by law” (Kang et al., 2016; p. 59), typically involves widely favored, prosocial issues, such as support for community groups and cancer research (Peloza & Shang, 2011). Since corporate activism involves polarized, hot-button sociopolitical issues, we suggest that it triggers a different psychological process. In the next section, we show that the effect of corporate activism on unethical consumer behavior toward the company is moderated by consumers’ political ideology and mediated by consumers’ desire to punish the company.

Political Ideology, Desire for Punishment, and Hypothesis Development

Political Ideology

Following extant work on corporate activism (Hydock et al., 2020; Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020), we focus on the congruence of a company’s sociopolitical stance with that of the consumer. While prior work has often examined consumers’ stance on each individual sociopolitical issue, more recent work measures political ideology as a more general variable to capture congruence (Garg & Saluja, 2022). Over the last few decades, Americans increasingly show affective polarization, disliking or distrusting those from the other political party (Iyengar et al., 2019). Along with this growing affective polarization, the nation’s major political parties have become more polarized on ideological identities (Finkel et al., 2020). As a result, Americans’ stances on polarizing sociopolitical issues have become increasingly aligned with their political ideology (Finkel et al., 2020). Given that an essential feature of corporate activism is the partisan nature of the issue (Bhagwat et al., 2020), political ideology is a theoretically-driven indicator of consumers’ positions on various sociopolitical issues. Using political ideology is also practically beneficial because it is easier for companies to collect information about a consumer’s political ideology than their stance on each individual issue.

Desire for Punishment

In the context of service failure, prior research has found that transgressions by a company can increase consumers’ desire to punish the company (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008). For example, when consumers perceived that the fairness norm was violated, they felt betrayed and wanted to punish the company (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008). The desire to punish can arise even when consumers are not directly harmed by the company’s transgression, e.g., when companies engage in child labor (Huber et al., 2010) or when companies are perceived as harmful (Rotman et al., 2018). Consumers may punish the company in various ways, including spreading negative word-of-mouth, vindictive complaining (e.g., complaining to cause inconvenience for and abuse its employees) (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008), and, importantly, engaging in unethical behavior (Rotman et al., 2018).

In the context of sociopolitical issues, consumers perceive others with a different view as violating fundamental moral foundations (Haidt, 2013), which can elicit strong negative emotions, such as anger and disgust (Molho et al., 2017). These hostile emotions can evoke the desire to punish opponents (Bonifield & Cole, 2007). Therefore, we expect that when a company takes a stand that is incongruent with consumers’ political ideology (vs. when there is no information), consumers will show an increased desire to punish the company because they perceive it as a moral violation and experience increased anger. In contrast, when a company takes a congruent stand, consumers may show a reduced desire to punish the company because they perceive that the company is engaging in moral behavior (Haidt, 2013). Further, we expect that the change in desire for punishment will affect consumers’ unethical behavior toward the company (Rotman et al., 2018).

H1

When a consumer’s political ideology is incongruent (congruent) with the company’s stand on a controversial sociopolitical issue, corporate activism (vs. no information) increases (decreases) unethical consumer behavior toward the company.

H2

Desire for punishment mediates the effect of corporate activism on unethical consumer behavior (H1).

Moderators

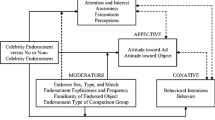

Figure 1 shows our conceptual framework. We propose two moderators that test different parts of the conceptual framework. Building on the desire for punishment mechanism, we propose that stance consistency attenuates the effect of corporate activism on the desire for punishment. The perceived immorality of unethical behavior attenuates the effect of desire for punishment on unethical behavior. Overall, these two moderators show situations in which consumers may not act unethically despite a company’s incongruent activism.

Moderating Role of Stance Consistency

Although many companies are politically neutral, some have the reputation of being “liberal” or “conservative.” For example, according to the 2019 Business Politics Survey, consumers perceived brands such as Nike, Starbucks, Apple, and Target as Democratic brands; in contrast, J.P. Morgan Chase, Nordstrom, Walmart, and Delta were perceived as Republican brands (Global Strategy Group, 2019).

These “liberal” or “conservative” brands typically take a stance on a sociopolitical issue consistent with their political reputation; however, they can also take a stance that is inconsistent with their reputation. For example, in 2022, Walmart took a liberal stance on abortion by announcing that it would expand abortion and related travel coverage for its employees (Repko, 2022). Similarly, in 2018 Delta announced that it would end discounts to the National Rifle Association after school shootings (Delta, 2008).

How does a company’s inconsistent stance moderate the impact of corporate activism on desire for punishment and unethical behavior? When the company’s current stance on a specific socio-political issue is consistent with their political reputation, consumers are clear about what the company stands for. When the company’s political reputation is unknown, consumers will infer the company’s political values from its current stance on a specific socio-political issue, as this the only information that they have. Thus, there is no conflicting information. However, when the company’s current stance on a specific-sociopolitical is inconsistent with their political reputation, consumers receive mixed information. This will lead to ambivalence and dampen their desire to punish the company. Our prediction aligns with work showing that providing conflicting product reviews leads consumers to have ambivalent attitudes toward the product (Akhtar et al., 2019). Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3

The effect of the company’s stand on a controversial sociopolitical issue on unethical consumer behavior is attenuated when the company’s political reputation is inconsistent with the stand, compared to when the company’s reputation is consistent or unknown.

Moderating Role of Perceived Immorality of Unethical Behavior

Although unethical behaviors violate generally accepted moral norms and principles, not all behaviors are perceived as equally immoral. Perceived immorality can be influenced by different aspects of behavior, such as its perceived legality and whether it provides someone active or passive benefits (Vitell & Muncy, 1992). For example, a customer giving misleading price information to a clerk (i.e., customer actively benefits) can be perceived as more immoral than not saying anything when a clerk miscalculates the price in the customer’s favor (i.e., customer passively benefits). Shoplifting can be perceived as more immoral than wardrobing because the former is illegal, while the latter is legal.

We expect that our proposed effect (H1) will be attenuated when unethical behavior is perceived as highly immoral. Specifically, although the company’s incongruent (vs. congruent) activism increases desire for punishment regardless of the perceived immorality of unethical behavior, desire for punishment will not lead to greater unethical behavior when the behavior is perceived as highly immoral. People are prone to engage in “minor” unethical behavior that can be easily justified and therefore does not damage their self-image, but they are reluctant to engage in severe unethical behavior (Mazar et al., 2008). In our context, since consumers can easily justify their moderately immoral behaviors, they may use them as a tool to punish a company engaged in incongruent activism. However, since consumers cannot easily justify engaging in highly immoral behavior, even when they have a strong desire to punish the company, they will not engage in such behavior. In summary, we hypothesize that:

H4

The effect of the company’s stand on a controversial sociopolitical issue on unethical consumer behavior is attenuated when unethical behavior is perceived as highly immoral.

Study Overview

We tested the hypotheses in five studies. Using actual unethical behavior, in study 1, we tested H1. Studies 2–3 replicated the findings of study 1 using intention for unethical behavior and showed support for the mediating role of desire for punishment (H2). Study 2 also examined the effect of remaining silent. Study 3 examined both corporate activism and CSR. Studies 4 and 5, respectively, tested two moderators: stance consistency (H3) and the perceived immorality of unethical behavior (H4). In studies 2–5, we rule out several alternative explanations: desire for reward, anticipatory self-view (i.e., consumers’ anticipation about how positively/negatively they would feel about themselves after acting unethically; Mazar et al., 2008), attitude towards the company, and perceived harmfulness of the company. While we use a single item political ideology measure in most studies, we use a multi-item measure in study 4. Across all studies, we report all observations, conditions, and measures. The materials and data of each study can be found on https://osf.io/u89t4/?view_only=938c8a7219b0483b92b75ccd5f6ffd73.

Study 1

Study 1 tests H1 that a consumer’s political ideology moderates the effect of corporate activism on unethical consumer behavior. To examine actual unethical behavior against the company, we adapted Gneezy’s (2005) deception game, in which participants had the opportunity to lie to an employee of the company to increase their monetary rewards. The polarizing sociopolitical issue was the banning of transgender athletes from competing in women’s sports. At the time of the study, 70% (18%) of Republicans opposed (supported) allowing transgender women to participate in women’s sports, while 26% (57%) of Democrats opposed (supported) the issue (Silverman, 2021).

Method

A total of 599 participants (50.6% female, Mage = 33.16, SD = 13.19) recruited from Prolific completed a 2 (corporate activism: present, no information) by continuous (political ideology—measured) between-subjects design study.Footnote 1

Participants first indicated their political ideology with a single item, “Do you consider yourself as politically liberal or politically conservative?” (1 = very liberal, 7 = very conservative) (Graham et al., 2009; M = 3.07, SD = 1.71).Footnote 2 This single-item political ideology measure has been widely used in both the psychology (Graham et al., 2009; Jost, 2006) and consumer behavior literature (e.g., Ordabayeva & Fernandes, 2018). After some filler questions, participants read that they would play a decision-making game sponsored by an educational program development company, CelTec. They saw a general description of CelTec and CelTec’s Twitter post about the effect of age on cognitive abilities (see Web Appendix A for the stimuli). Participants in the activism present condition saw an additional post from CelTec about its support for a Mississippi bill that would ban transgender athletes from competing in women’s sports. Thus, the company’s stance was congruent (incongruent) with conservatives (liberals). Specifically, the Twitter post stated:

CelTec recently signed a letter expressing our support for a Mississippi bill that would ban transgender athletes from competing on girls or women’s sports teams. The Mississippi bill will create fair competition by limiting women’s sports to women based on their biological sex.

Next, all participants read that they would be randomly matched with a CelTec employee and could win either $0.10 or $0.20 as a bonus payment based on which option the CelTec employee selected. Option A would give $0.10 to the participant and $0.20 to the CelTec employee; Option B would give $0.20 to the participant and $0.10 to the CelTec employee. Thus, the participant would win more money if the CelTec employee chose Option B. The funds for the bonus payment were said to be provided by CelTec.

Participants then chose one of two messages to send to the CelTec employee. Message 1 was accurate, stating that “Option A will earn you more than Option B.” Message 2 was a lie, stating that “Option B will earn you more than Option A.” Before making the message choice, participants were informed that the CelTec employee would not know the amount of the monetary payments associated with each option (Option A or B). Thus, the CelTec employee would be relying on the participant’s message to make a choice (see Web Appendix A for the detailed instructions).

After the choice, we assessed whether participants understood the instructions correctly (“Did you understand the instructions”: Yes or No) and whether participants considered the other player as a CelTec employee: “I considered the other player as” (1) The CelTec employee, (2) friend, and (3) other (specify). Participants who chose to send Message 1 (Message 2) received a bonus payment of $0.10 ($0.20). Lastly, participants were debriefed that the decision-making game was not funded by CelTec and the other player was not a CelTec employee.

Results

Five participants indicated that they did not understand the instructions and 26 indicated that they did not consider the other player as a CelTec employee. When we excluded these 31 participants from the analysis, the results remained unchanged.Footnote 3 Therefore, we report the results with all participants.

To test H1, we ran a binary logistic regression using corporate activism (0 = no information, 1 = present), mean-centered political ideology, and the interaction term as independent variables and unethical behavior (0 = not-lying, 1 = lying) as the dependent variable. There were significant main effects of activism (b = 0.36, SE = 0.17, Wald χ2(1) = 4.77, p = 0.029) and political ideology (b = 0.14, SE = 0.07, Wald χ2(1) = 4.13, p = 0.042) as well as a significant interaction (b = -0.29, SE = 0.10, Wald χ2(1) = 8.54, p = 0.003; see Fig. 2). The Johnson-Neyman analysis revealed that corporate activism (vs. no information) significantly increased unethical behavior when the stand was incongruent with participants’ political ideology (i.e., liberal, PI ≤ 3.20; Probability of lying: 57.5% in activism vs. 49.4% in no information; b = 0.33, SE = 0.17, p = 0.05), but marginally decreased unethical behavior when the stand was congruent (i.e., conservative, PI = 7; Probability of lying: 44.0% in activism vs. 63.0% in no information; b = -0.76, SE = 0.42, p = 0.068). Overall, this finding provides initial support for H1 using lying to a company’s representative as an incentive-compatible unethical behavior.

Study 2

Study 2 had multiple objectives. Besides replication, we tested the mediating role of desire for punishment (H2). Second, we ruled out several alternative explanations, including desire for reward, anticipatory self-view, perceived harmfulness of the company, and company attitude. For desire for reward, an argument could be that an increased desire for reward rather than a decreased desire for punishment explains the positive effect of congruent activism on unethical behavior. However, we think this is unlikely based on the two-level moral regulation theory. This theory states that prescriptive morality—involving activating “good” behaviors (e.g., helping others)—is associated with positive emotions and outcomes, such as feeling pleasant and getting rewards; proscriptive morality—involving inhibiting “bad” behaviors (e.g., do not lie to others)—is associated with negative emotions and outcomes, such as feeling unpleasant and receiving punishment (Janoff-Bulman et al., 2009). Because the decision to act unethically involves proscriptive morality, it is likely to be influenced by the desire of negative valence: desire for punishment. Although prior research suggests that desire for reward is not likely to mediate the positive effect of congruent activism on unethical behavior, we measured and tested it to empirically rule out. Third, we added another control condition in which a company remains silent (i.e., refuses to take a stand) when they are asked to speak on a sociopolitical issue. Finally, we generalized our finding to a different activism issue: the impeachment of President Donald Trump, which became salient after the January 2021 Capitol riots. A public poll showed that 92% of Democrats and 13% of Republicans supported impeachment (Monmouth University, 2021). Note that in study 1, the company stance was congruent (incongruent) with conservatives (liberals). In this study, the company stance, supporting the impeachment of President Donald Trump, was congruent (incongruent) with liberals (conservatives).

Method

A total of 601 participants (50.2% female, Mage = 34.08, SD = 12.89) from Prolific completed a 3 (corporate activism: taking a stand, silence, no information) by continuous (political ideology—measured) between-subjects design.

After the single-item political ideology measure used in study 1 (M = 3.00, SD = 1.67), all participants viewed the Facebook page of a hypothetical American clothing brand and retailer, Lawson. Participants in the taking a stand and silence conditions also read an excerpt from a news article about Lawson. In the taking a stand condition, the article mentioned that the CEO of Lawson tweeted support for the National Association of Clothing Manufacturers’ call for the removal of the President Donald Trump from office. In the silence condition, the article mentioned that when asked about the company’s stand on this issue, the CEO remained silent (see Web Appendix A for stimuli).

Then, all participants read the following scenario where they could engage in wardrobing.

Imagine that you bought a shirt at a local Lawson store. After wearing the shirt once, which looks clean and still has a tag on it, you see another shirt of a similar design and quality for a substantially lower price at another clothing store. The return policy of Lawson is that “Customers can return unworn merchandise for a full refund.

Participants then indicated their intention to act unethically, anticipatory self-view, and desire to punish the company. The intention to act unethically was measured by one item (“How likely would you be to return the T-shirt to Lawson for a full refund?” 1 = very unlikely, 7 = very likely). We measured anticipatory self-view by asking how participants would feel about themselves if they returned the shirt to Lawson using two bipolar scales: “bad about myself – good about myself” and “I am a bad person—I am a good person” (r = 0.85). We measured anticipatory self-view to rule out the alternative explanation that congruent (incongruent) corporate activism might decrease (increase) unethical behavior because consumers anticipate feeling worse (better) about their moral self-view after cheating the company having the same stance as (the opposite stance to) themselves (Mazar et al., 2008). Desire for punishment was measured with two items: (a) “I want to punish Lawson in some way” and (b) “I want to get even with Lawson” (1 = not at all, 7 = very much; r = 0.91; adapted from Grégoire et al., 2009).

We also measured desire to reward the company, perceived harmfulness of the company, and attitude toward the company as alternative explanations. Desire for reward was measured with two items: (a) “I want to reward Lawson in some way” and (b) “I want to help Lawson” (1 = not at all, 7 = very much; r = 0.92). The perceived harmfulness of the company was measured with five items adopted from Rotman et al. (2018): harmful, mean, hostile, peaceful (reverse-coded), and gentle (reverse-coded) (1 = not at all, 7 = very much; α = 0.69). Attitude toward the company was captured with three bipolar items: negative/positive, dislike/like, and unfavorable/favorable (α = 0.97). Note that we also measured these three alternative mediators along with anticipatory self-view in studies 3 and 5 and found that none of these variables reliably mediated the effect of corporate activism on intention for unethical behavior. This suggests that we can rule them out as alternative explanations. We present the detailed results of these variables in Web Appendix B due to space constraints.

We measured the perceived effort in supporting the issue for exploratory purpose to examine whether consumers perceive that the company exerted more effort in supporting the issue when taking a stance versus remaining silent. Finally, we measured the manipulation recall check question in the taking a stance and silence conditions. Overall, most participants (99.0% in taking a stance condition; 86.4% in the silence condition) correctly recalled the manipulation. We present the measures and results of these variables in Web Appendix B.

Results

Intention to act unethically

We ran a regression with intention for unethical behavior as the dependent variable, and two dummy variables for corporate activism using the no information condition as the baseline (taking a stand dummy: 0 = no information, 1 = taking a stand, 0 = silence; silence dummy: 0 = no information, 0 = taking a stand, 1 = silence), mean-centered PI, and the two two-way interaction terms as independent variables. Our main focus was H1, the interaction between the taking a stand dummy and political ideology. The main effect of taking a stand was not significant (b = − 0.28, SE = 0.22, t(595) = − 1.30, p = 0.19). Importantly, the interaction between taking a stand and political ideology was significant (b = 0.35, SE = 0.13, t(595) = 2.78, p = 0.006; See Fig. 3). The Johnson-Neyman analysis revealed that taking an activism stand (vs. no information) significantly increased unethical behavior intention when the company’s stand was incongruent with participants’ political ideology (i.e., conservative, PI ≥ 6.44; Mstand = 4.43 vs. MNoInf = 3.49; bJN = 0.93, SE = 0.48, p = 0.050), but significantly decreased intention when the stand was congruent (i.e., liberal, PI ≤ 2.53; Mstand = 3.20 vs. MNoInf = 3.65; bJN = -0.45, SE = 0.23, p = 0.050).

Next, to compare the effect of taking a stand with silence as a control condition, we ran a second regression replacing the two dummy variables with the ones using silence as the baseline (silence-taking a stand dummy: 0 = no information, 1 = taking a stand, 0 = silence; silence-control dummy: 1 = no information, 0 = taking a stand, 0 = silence). The main effect of silence-taking a stand was significant (b = -0.68, SE = 0.22, t(595) = -3.12, p = 0.002), which was qualified by the significant interaction between silence-taking a stand and political ideology (b = 0.53, SE = 0.13, t(595) = 4.06, p < 0.001). The Johnson-Neyman analysis revealed that taking an activism stand (vs. silence) increased intention for unethical behavior when the stand was incongruent with political ideology (PI ≥ 5.95; Mstand = 4.27 vs. Msilence = 3.38; bJN = 0.89, SE = 0.46, p = 0.050), but significantly decreased intention when the stand was congruent (PI ≤ 3.43; Mstand = 3.49 vs. Msilence = 3.94; bJN = − 0.45, SE = 0.23, p = 0.050). Overall, the effects of taking an activism stand on unethical behavior intention were similar when we used both no information and silence as control groups, further supporting H1.

Finally, to compare the effect of silence (vs. no information condition), we returned to our first regression. The main effect of silence was marginally significant (b = 0.40, SE = 0.22, t(595) = 1.83, p = 0.067). The interaction between silence and political ideology was not significant (b = − 0.18, SE = 0.13, t(595) = − 1.36, p = 0.18). This suggests that remaining silent (vs. no information) marginally increased unethical behavior.

Desire for Punishment

For desire for punishment, we first compared no information versus taking a stand. The main effect of taking a stand was not significant (b = 0.08, SE = 0.16, t(595) = 0.49, p = 0.62), while the interaction between taking a stand and political ideology was significant (b = 0.32, SE = 0.09, t(595) = 3.49, p = 0.001). As expected, the Johnson-Neyman analysis revealed that taking a stand (vs. no information) significantly increased desire for punishment when the stand was incongruent with political ideology (PI ≥ 3.79; Mstand = 2.24 vs. MNoInf = 1.90; bJN = 0.33, SE = 0.17, p = 0.050), and significantly decreased desire for punishment when the stand was congruent (PI ≤ 1.42; Mstand = 1.28 vs. MNoInf = 1.71; bJN = -0.43, SE = 0.22, p = 0.050). We report the results comparing between silence and taking a stand and comparing no information and silence in Web Appendix B due to space constraint. The pattern of results was similar to that of intention for unethical behavior.

Parallel Moderated Mediation Analysis

To test H2, we included all five potential mediators as parallel mediators using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 8; 5000 bootstraps; Hayes, 2018). We included corporate activism as the independent variable; political ideology as the moderator; desire for punishment, anticipatory self-view, desire for reward, perceived harmfulness, and company attitude as the parallel mediators; and unethical behavior intention as the dependent variable. Note that we included the ‘mcx = 1’ option to the SPSS syntax to define corporate activism as a multi-categorical variable with three levels. ‘mcx = 1’ dictates SPSS to create two dichotomous variables from the independent variable with three levels using dummy coding. This allows us to compare the two levels of the independent variable. In this study, our focus is to compare the effect of (a) taking a stance versus no information, and (b) taking a stance versus silence. Since we expected different indirect effects depending on participants’ political ideology, we tested the indirect effects at all intervals of political ideology (see Table 1).

As expected, the indexes of the moderated mediation of the desire for punishment were significant. More specifically, consistent with H2, when the activism stand was [incongruent/congruent] with consumers’ political ideology, desire for punishment [positively/negatively] mediated the effect of taking a stand (vs. no information or silence) on intention for unethical behavior (H2).

The indirect effect of anticipatory self-view was not significant at any level of political ideology when explaining the effect of taking a stand (vs. no information) on unethical behavior intention, although anticipatory self-view was a significant mediator when explaining the effect of taking a stand (vs. silence). Moreover, the mediating effects of desire for reward and harmfulness perception were not significant although the mediating effect of company attitude was significant. (However, in subsequent studies, company attitude was not a significant mediator.) Overall, these results suggest that anticipatory self-view, desire for reward, and perceived harmfulness cannot explain the effect of taking a stand on unethical behavior.

Note that when we included the desire for punishment as the sole mediator, the pattern of results for the indirect effects of the desire for punishment remained the same (See Table 2).

Discussion

Using no information and silence as control conditions, we replicated the findings of study 1 and showed that desire for punishment was a significant mediator. Interestingly, remaining silent (vs. no information) increased desire for punishment and intention for unethical behavior. This find is consistent with Silver and Shaw’s finding (2022) that remaining silent on political issues can backfire. We discuss the role of silence in the General Discussion.

Study 3

In this study, we compared the effects of corporate activism with those of CSR. Prior research makes a conceptual distinction between CSR and corporate activism (Bhagwat et al., 2020). While CSR involves non-controversial prosocial issues, corporate activism involves controversial sociopolitical issues. As a result, activism might increase anger and thus desire for punishment (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008), while CSR is less likely to do so. Therefore, we expected that the desire for punishment would mediate the effects of activism but not CSR. Building on List and Momeni (2021), we expected that CSR would increase unethical behavior regardless of consumers’ political ideology, and anticipatory self-view would be a mediator. As in study 1, the activism issue concerned transgender athletes. The CSR issue was supporting hungry children, which has been widely used in prior literature (Peloza & Shang, 2011).

Method

A total of 799 participants (47.3% female, Mage = 33.87, SD = 12.13) from Prolific completed a 3 (taking a stand: corporate activism, CSR, no information) by continuous (political ideology—measured) between-subjects design.

After indicating political ideology as before (M = 3.03, SD = 1.68) and completing filler questions, participants viewed the Facebook page of a fictitious American sportswear retailer, Rentik. They also viewed a post from Rentik that advertised its newly released pants. Participants in the activism (CSR) condition viewed another Rentik post that showed its support for an Arkansas bill that would ban transgender athletes from competing in high school girls’ sports (a charity that supported hungry children) (see Web Appendix A for stimuli). Then, all participants read the scenario that was similar to Study 2 where they could engage in wardrobing.

We then measured intention to act unethically, anticipatory self-view (r = 0.87), desire to punish (r = 0.84) and reward the company (r = 0.92), perceived harmfulness of the company (α = 0.86), and company attitude (α = 0.97) using the same items as in study 2. We also measured manipulation checks for corporate activism and CSR. The manipulation worked as intended. See details in Web Appendix B.

Results

Intention to Act Unethically

We ran a regression with intention for unethical behavior as the dependent variable, and two dummy variables for taking a stand using the no information as the baseline (activism dummy: 0 = no information, 1 = activism, 0 = CSR; CSR dummy: 0 = no information, 0 = activism, 1 = CSR), mean-centered political ideology, and the two two-way interaction terms as the independent variables. The interaction between the activism dummy and political ideology, testing H1, was our main focus. There was a significant main effect of activism (b = 0.59, SE = 0.18, t(793) = 3.19, p = 0.001), qualified by a significant interaction between activism and political ideology (b = -0.43, SE = 0.11, t(793) = -4.04, p < 0.001; See Fig. 4). As predicted, the Johnson-Neyman analysis revealed that taking an activism stand (vs. no information) significantly increased intention for unethical behavior when the stand was incongruent with political ideology (i.e., liberal, PI ≤ 3.53; Mstand = 3.90 vs. MNoInf = 3.53; bJN = 0.37, SE = 0.19, p = 0.050), and significantly decreased intention when the stand was congruent (i.e., conservative, PI ≥ 6.07; Mstand = 2.78 vs. MNoInf = 3.50; bJN = − 0.73, SE = 0.37, p = 0.050).

We next compared CSR versus no information. There was a significant main effect of CSR (b = − 0.50, SE = 0.18, t(793) = − 2.72, p = 0.007); however, the interaction between CSR and political ideology was not significant (b = − 0.08, SE = 0.11, t(793) = − 0.70, p = 0.48). CSR (vs. no information) reduced participants’ intention to act unethically towards the company regardless of their political ideology. This finding is inconsistent with List and Momeni’s (2021) finding that CSR increases unethical behavior. We discuss this finding in the General Discussion.

Desire for Punishment

The pattern of results for desire for punishment was similar to that of intention for unethical behavior. There was a significant main effect of activism (b = 1.24, SE = 0.12, t(793) = 10.22, p < 0.001), qualified by a significant interaction between activism and political ideology (b = − 0.46, SE = 0.07, t(793) = − 6.53, p < 0.001). The Johnson-Neyman analysis revealed that taking an activism stand (vs. no information) significantly increased desire for punishment when the stand was incongruent with political ideology (PI ≤ 4.95; Mstand = 2.07 vs. MNoInf = 1.72; bJN = 0.35, SE = 0.18, p = 0.050), and marginally significantly decreased intention when the stand was congruent (PI = 7; Mstand = 1.25 vs. MNoInf = 1.84; bJN = − 0.59, SE = 0.31, p = 0.051).

When comparing CSR versus no information, the main effect of CSR as well as the interaction between CSR and political ideology were not significant (ps > 0.51). This suggests that CSR did not influence consumers’ desire to punish the company.

Parallel Moderated Mediation Analysis

To test H2, we included all five potential mediators (anticipatory self-view, desire for punishment, desire for reward, perceived harmfulness, and company attitude) as parallel mediators and political ideology as a moderator using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 8; 5,000 bootstraps). Replicating the findings of study 2, desire for punishment positively [negatively] mediated the effect of corporate activism (vs. no information) on intention for unethical behavior when the activism stand was incongruent [congruent] with political ideology (see Table 3). Furthermore, the index of the moderated mediation of the desire for punishment was significant. This provides further support for the desire for punishment mechanism (H2). However, when comparing CSR (vs. no information), the mediating effect of desire for punishment was not significant at any level of political ideology, suggesting that desire for punishment cannot explain the effect of CSR on unethical behavior.

The indirect effect of anticipatory self-view in explaining the effect of corporate activism (vs. no information) on unethical behavior was significant when the activism stand was incongruent, but not when it was congruent. Unexpectedly, anticipatory self-view also did not significantly mediate the effect of CSR (vs. no information). Moreover, the indirect effects of the other mediators (desire for reward, perceived harmfulness of the company, and company attitude) were not significant at any level of political ideology either for activism or for CSR.

Note that when we included the desire for punishment as the sole mediator, the pattern of results for the indirect effects of the desire for punishment remained the same (see Table 4).

Discussion

Study 3 demonstrates that the effects of corporate activism on intention for unethical behavior differ from those for CSR. For corporate activism, we replicated the findings of studies 1 and 2, with desire for punishment as a significant mediator. In contrast, CSR decreased intention for unethical behavior. Neither desire for punishment nor anticipatory self-view mediated the effect of CSR on intention for unethical behavior.

Study 4

The objective of study 4 was to provide further support for the desire for punishment mechanism by testing the moderating role of stance consistency (H3). We predicted that when a company’s stance was inconsistent, the proposed effect of corporate activism on desire for punishment and unethical behavior would be attenuated.

We also made some methodological changes in this study. To ensure that our results were robust to different measures of political ideology, we used a multiple-item, issue-based measure (Kidwell et al., 2013). We measured political ideology at the end rather than the beginning of the survey to mitigate demand effect concerns. Also, we recruited the same number of liberal and conservative participants using CloudResearch’s prescreening feature and used a different activism issue (abortion) for further generalization. Abortion was a hot issue after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June 2022. A poll by Pew Research Center (2022) showed that 90% of liberals indicated that abortion should be legal in all or most cases whereas 72% of conservatives indicated that abortion should be illegal in all or most cases.

Method

We recruited 250 participants who identified themselves as liberal and 250 participants who identified themselves as conservative on MTurk (55.6% female, Mage = 42.57, SD = 13.63). The design was a 2 (stance consistency: inconsistent, unknown) by continuous (political ideology—measured) between-subjects design. Note that all participants were assigned to the corporate activism condition. We decided not to include the no information condition where a company does not take any stance on an issue a priori because we observed robust effects that political ideology did not affect unethical behavior in the no information condition in studies 1–3.

All participants read a general description of a fictitious American sportswear retailer, Rentik. Only participants in the inconsistent stance condition read the following paragraph showing the company is known for its conservative political values:

Rentik’s company values are influenced by the traditional beliefs of its founder. Rentik has so far taken conservative public stances on various social issues, including the rejection of vaccine mandate, supporting gun rights, and the opposition of LGBTQ issues.

Then, all participants read that Rentik recently took a liberal stance on abortion and that Rentik would support travel expenses for employees for abortion (see Web Appendix A for stimuli).

Participants then indicated their desire to reward (r = 0.96) or punish (r = 0.86) the company, followed by the intention to wardrobing using the same items used in study 3. As alternative explanations, we measured feelings of suspicion, betrayal, and gratitude toward the company. Some consumers can feel either suspicious or betrayed when a company’s stance is inconsistent with its political reputation. Others may feel grateful that the company has changed its stance from its political reputation. Overall, we ruled out these three alternative explanations (see Web Appendix B for detailed results).

Finally, we measured political ideology using both the single-item scale used in studies 1–3 (M = 3.97, SD = 2.19) as well as the multi-item scale (Kidwell et al., 2013; M = 3.67, SD = 1.66) in which participants indicated the extent to which they were in favor of or are against the following issues: capital punishment, abortion*, gun control*, socialized healthcare*, same-sex marriage*, illegal immigration*, increased military spending, and national Rifle association, where * marks reversed items (α = 0.90; 1 = strongly against, 7 = strongly favor). We did not include two items in the original scale (democrats and republicans), because they capture self-reported political identity, which is similar to the single-item measure. The single-item measure and the composite of multiple-item measure were highly correlated (r = 0.86).

Results

Intention to act unethically

We ran a regression with intention for unethical behavior as the dependent variable, and stance consistency (0 = unknown, 1 = inconsistent), mean-centered multi-item PI measure, and the interaction term as the independent variables. The main effect of stance consistency was not significant (b = 0.24, SE = 0.20, t(496) = 1.16, p = 0.25). The main effect of political ideology was significant (b = 0.50, SE = 0.09, t(496) = 5.56, p < 0.001). As predicted by H3, there was a significant interaction between stance consistency and political ideology (b = − 0.53, SE = 0.12, t(496) = − 4.34, p < 0.001; See Fig. 5). The simple main effect analysis replicated prior findings that when the company’s stance was unknown, participants with incongruent (vs. congruent) political ideology with the company’s current liberal activism stand showed higher intention for unethical behavior (b = 0.50, SE = 0.09, t(496) = 5.56, p < 0.001). However, when the company’s stance was inconsistent with their prior reputation, the intention for unethical behavior was not different among participants with incongruent and congruent political ideology (b = − 0.03, SE = 0.09, t(496) = − 0.40, p = 0.69). This finding supports H3 by showing that the effect of the company’s stand on a sociopolitical issue on unethical behavior was attenuated when the company’s political reputation was inconsistent with the stand.

The results were similar when the single-item ideology scale or the dichotomous ideology variable used to recruit participants with liberal or conservative ideology was used in the analysis. See Web Appendix C.

Desire for Punishment

For desire for punishment, the main effect of stance consistency was not significant (b = 0.13, SE = 0.15, t(496) = 0.89, p = 0.37). The main effect of political ideology was significant (b = 0.51, SE = 0.07, t(496) = 7.69, p < 0.001) as was the interaction effect between stance consistency and political ideology (b = − 0.24, SE = 0.09, t(496) = − 2.66, p = 0.008). The simple main effect analysis shows that participants with incongruent (vs. congruent) political ideology showed higher desire for punishment in both unknown (b = 0.51, SE = 0.07, t(496) = 7.69, p < 0.001) and inconsistent stance conditions (b = 0.27, SE = 0.06, t(496) = 4.36, p < 0.001). However, the significant interaction effect suggests that the effect was significantly attenuated in the inconsistent stance condition.

Parallel Moderated Mediation Analysis

We tested the role of all potential mediators as parallel mediators using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 8; 5000 bootstraps). We included political ideology as the independent variable; stance consistency as the moderator; desire for punishment, desire for reward, feelings of suspicion, betrayal, and gratitude as the parallel mediators; and intention for unethical behavior as the dependent variable.

Desire for punishment significantly mediated the effect of political ideology on unethical behavior intention both in the unknown (B = 0.09, 95% CI [0.00, 0.18]) and inconsistent stance conditions (B = 0.05, 95% CI [0.00, 0.10]). Importantly, the index of the moderated mediation was significant (B = − 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.10, − 0.00]), suggesting that the indirect effect of desire for punishment was significantly smaller in the inconsistent (vs. unknown) stance condition. The indirect effects of all other mediators were not significant. When we included the desire for punishment as the sole mediator, the results remained similar.

Study 5

The objective of study 5 was to test the moderating role of perceived immorality of unethical behavior (H4). To identify unethical behaviors that are perceived as moderately or highly immoral, we conducted a pretest on Prolific (N = 50). Participants indicated the perceived immorality of 11 behaviors on three items: immoral, unethical, and wrong (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), along with other measures. Two behaviors were the same as used in studies 1–3, including lying to a company employee to get more money in a decision-making game (study 1) and wardrobing (studies 2–4). These two behaviors were perceived as moderately immoral (lying in a game: M = 4.73, wardrobing: M = 4.67). Shoplifting (M = 5.93) was perceived as highly immoral. Therefore, we used wardrobing (shoplifting) as a moderately (highly) immoral behavior.

Method

The study used a 2 (perceived immorality of unethical behavior: moderate, high) by continuous (political ideology—measured) between-subjects design. Participants were 257 undergraduates (39.3% female, Mage = 20.42, SD = 2.05) at a large American university. Three participants did not indicate their political ideology, leaving 254 participants for the analysis. All participants were assigned to the corporate activism condition.

Participants indicated their political ideology using the single-item measure (M = 3.71, SD = 1.49) in a separate survey conducted by other researchers. Participants viewed a Facebook page of the American sportswear manufacturer and retailer, Lawson, and a Facebook post that advertised its newly released pants. Participants then viewed the Facebook post that showed Lawson’s support for a Kansas bill that would ban transgender athletes from competing in middle and high school girls’ sports. Then, participants in the moderately (highly) immoral behavior condition read the wardrobing (shoplifting) scenario (see Web Appendix A for the stimuli).

They then indicated their intention to act unethically, anticipatory self-view (r = 0.90), desire to reward (r = 0.97) or punish (r = 0.91) the company, the perceived probability of getting caught (r = 0.64), perceived harmfulness of the company (α = 0.83), and company attitude (α = 0.98). The same items were used as in studies 2–3, except for the perceived probability of getting caught. We measured the perceived probability of getting caught with two items (“What is the likelihood that you would get caught when you [return the T-shirt to Lawson for a full refund/take the T-shirt without paying for it]?”; 1 = very unlikely, 7 = very likely, and “I am concerned that I would get caught when I [return the T-shirt to Lawson for a full refund/take the T-shirt without paying for it]”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; r = 0.64) to control for potential differences across the two unethical behaviors.

Results

Intention to Act Unethically

We ran a regression with intention for unethical behavior as the dependent variable, and perceived immorality of unethical behavior (0 = moderate, 1 = high), mean-centered PI, and the interaction term as the independent variables. The main effects of perceived immorality (b = − 2.23, SE = 0.25, t(250) = − 8.99, p < 0.001) and political ideology (b = − 0.38, SE = 0.12, t(250) = -3.08, p = 0.002) were significant. As predicted by H4, the interaction effect between perceived immorality and political ideology was significant (b = 0.39, SE = 0.17, t(250) = 2.30, p = 0.022; See Fig. 6). The simple main effect analysis replicated prior findings in the moderate immorality condition in that participants with the incongruent (vs. congruent) political ideology showed higher intention for unethical behavior (b = − 0.38, SE = 0.12, t(250) = -3.08, p = 0.002). However, in the high immorality condition, participants with both incongruent and congruent political ideology showed equally low intention (b = 0.01, SE = 0.11, t(250) = 0.06, p = 0.95). The results did not change when we included the probability of getting caught as a covariate.

Desire for Punishment

As expected, only the main effect of political ideology was significant (b = − 0.35, SE = 0.11, t(250) = − 3.28, p = 0.001). Neither the main effect of perceived immorality nor the interaction effect was significant (ps > 0.54). This suggests that participants with incongruent (vs. congruent) political ideology showed higher desire for punish the company in both the moderate and high immorality conditions.

Parallel Moderated Mediation Analysis

We tested the role of all potential mediators as parallel mediators using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 8; 5000 bootstraps). We included political ideology as the independent variable; perceived immorality of unethical behavior as the moderator; anticipatory self-view, desire for punishment, desire for reward, perceived harmfulness of the company, company attitude, and probability of getting caught as the parallel mediators; and intention for unethical behavior as the dependent variable.

Unexpectedly, desire for punishment did not significantly mediate the effect of political ideology on unethical behavior intention both in the moderate (B = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.05, 0.07]) and high immorality conditions (B = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.03, 0.05]). However, when we only included desire for punishment as a mediator, the indirect effect of desire for punishment was significant both in the moderate (B = − 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.14, − 0.01]) and high immorality conditions (B = − 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.10, − 0.00]). Anticipatory self-view was a significant mediator in the moderate immorality condition (B = − 0.20, SE = 0.09, 95% CI − 0.38, − 0.03), but not in the high immorality condition (B = − 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.16, 0.14]). The mediating effects of all other mediators were not significant.

Discussion

We found that when unethical behavior was perceived as highly immoral, incongruent corporate activism did not lead to increased unethical behavior despite a desire to punish the company, providing support for H4. This suggests that consumers have constraints on the types of unethical behavior they may engage in to punish companies.

General Discussion

We examined when and how corporate activism influences consumers’ unethical behavior toward companies. Across five studies using different sociopolitical issues (transgender athletes, impeachment of President Donald Trump, and abortion) and different unethical behaviors (lying to a company’s representative for monetary rewards and wardrobing), we find that the effect of corporate activism on unethical behavior is moderated by consumers’ political ideology and mediated by desire for punishment. When the company’s activism stand is incongruent (congruent) with the consumers’ political ideology, consumers experience the increased (decreased) desire to punish the company, thereby increasing (decreasing) unethical behavior toward the company. Furthermore, we present two theoretically driven boundary conditions. Unethical behavior is attenuated when the company’s stance is inconsistent with its political reputation (study 4) and when the unethical behavior is perceived as highly immoral (study 5).

Theoretical and Managerial Contributions

The current research adds to the growing literature on corporate activism (e.g., Hydock et al., 2020; Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020) by demonstrating that corporate activism can motivate consumers to engage in behaviors that sacrifice their moral values to punish the company. Given the growing political polarization in the United States as well as in many other countries, consumers’ desire to punish a company by behaving unethically towards it may increase in the future. Although public surveys on corporate activism inquire about the likelihood of engaging in buycotting, boycotting, and word-of-mouth behavior (Edelman, 2022), they do not ask about unethical behaviors due to social desirability bias. Our work suggests that capturing this type of behavior is important from both a theoretical and practical perspective.

Another contribution of the paper is in identifying desire for punishment as the underlying mechanism while ruling out other alternative mechanisms. Our desire for punishment mechanism is different from other mechanisms, such as positive emotions (Garg & Saluja, 2022), brand identification (Hydock et al., 2020), and balance theory (Jungblut & Johnen, 2022), which were used to explain the effect of activism on brand attitudes, purchase intentions, or brand choice. Furthermore, we show that desire for reward—the motivation of positive valence—did not mediate the effect of corporate activism on unethical behavior. We also showed that our effect was not explained by company attitude or perceived harmfulness of the company. Rotman et al. (2018) found that when companies engage in actions perceived as harmful, consumers punish them by behaving unethically. However, perceived harmfulness did not account for our effects. Mukherjee and Althuizen (2020) found that incongruent corporate activism reduced company attitudes. However, company attitude did not explain our results. This suggests that the process underlying unethical behavior is different from other behaviors examined in prior studies. This highlights the importance of studying unethical behavior as another consequence of corporate activism.

We acknowledge that some papers view boycotting in response to corporate activism as a punishment behavior. For example, Jungblut & John (2022) cited Friedman (1999) who theorized boycotting as behavior in which people punish a company for specific business practices. However, Jungblut and John’s mechanism for the effects of activism on boycotting/buycotting was balance theory, not desire for punishment. Friedman’s (1999) book about boycotting and buycotting in general does not provide empirical tests of desire for punishment as a mechanism. Thus, our investigation and empirical evidence for desire for punishment as the underlying mechanism is different from prior research on activism.

We further enhance the understanding of the desire for punishment mechanism by identifying a theoretically driven moderator: stance consistency. Our findings of study 4 provide a nuanced managerial implication by showing that even when a company’s stance on a specific political issue is incongruent with consumers’ political ideology, its inconsistent political reputation can buffer it from negative consumer responses. A question for future research is whether we would get the same result if consumers had high self-brand connection with the company who changed its stance. On the one hand, high self-brand connection may protect the brand from negative effects (Ferraro et al., 2013) by attenuating consumers’ desire for punishment. However, highly connected consumers may sometimes feel betrayed by a company’s actions (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008), which would increase the desire for punishment.

We demonstrated another boundary condition, that not all unethical behavior is affected by corporate activism. In study 5, despite a desire to punish the company, participants were unwilling to engage in shoplifting, which they perceived as highly immoral. This indicates that consumers have limits on how much they are willing to engage in unethical behavior as a result of activism.

Finally, study 3 illustrates that desire for punishment leads to unethical behavior when a company engages in activism rather than CSR. Because CSR involves less controversial issues than activism, it does not lead to as strong emotional reactions. CSR does not influence desire for punishment, which also does not mediate the effect of CSR on unethical behavior. Thus, we show that the effects of CSR are different from those of corporate activism.

Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

In study 3, CSR decreased consumers’ intention for unethical behavior, which is in contrast to List and Momeni’s (2021) finding that CSR increased employee’s unethical behavior toward the company. We conjecture that this difference may have resulted from the difference in the relationship closeness between consumer-company and employee-company. Prior work has shown that a company’s CSR activity is more likely to trigger moral licensing when consumers have a stronger sense of connection with the company (Newman & Brucks, 2018). To prevent consumers’ existing company perceptions and attitudes from affecting their unethical behavior toward the company, we examined the effect of activism using hypothetical companies. In List and Momeni’s (2021) contexts, employees also did not have an existing relationship with a company because they were hired by the company (i.e., researchers) at the beginning of the study. However, employees’ baseline level of connection with the company may be higher than that of consumers, since employees depend on the company for a living. This may explain why the moral licensing process was activated in List and Momeni’s context, but not in our context.

Future research can also examine what happens when the company refuses to take a stand on a controversial issue. In study 2, we found that remaining silent (vs. no information) increased the desire for punishment and intention for unethical behavior. Consistent with Silver and Shaw’s (2022) finding, consumers may perceive the company remaining silent on a sociopolitical issue as deceptive, which may increase desire for punishment. Second, as more and more consumers believe that companies should solve important sociopolitical issues (Edelman, 2022), they may perceive the company remaining silent as not socially responsible, which can increase desire for punishment. Future research can systematically examine the mechanisms underlying the effects of company silence.

Another interesting question for future research is whether consumers’ desire for punishment toward a company taking a stance on a controversial issue spills over to other companies in the same/related product category that do not take such stance. For instance, liberal consumers would feel the desire to punish a focal sports apparel brand that took a conservative stance on the abortion issue. Would liberal consumers feel the same way toward other sports apparel brands that do not take any stance? One possibility is that liberal consumers perceive that other brands are intentionally staying silent, which could evoke a desire to punish other brands (cf. study 2). Another possibility is that liberal consumers view other brands that did not take any stance more positively than the focal brand that took the conservative stance, which could lower a desire for punishment for other brands. A potential moderator is the extent to which the other sportswear brands are associated in the minds of the consumers, i.e., whether they are categorized similarly in the consumer’s mind. Future research can examine these two possibilities.

Data availability

The materials and data of the studies are available at https://osf.io/u89t4/?.

Notes

We collected data in two batches. We originally intended to collect 600 participants. The first author, who launched the study on Prolific, accidentally recruited 400 participants and received 401 responses. Then, the first author additionally recruited 200 participants and received 198 responses.

To examine whether participants’ political ideology can be used as a proxy for their stance on the focal sociopolitical issue, we measured whether participants considered the focal issue as congruent or incongruent with their self-concept in studies 1 and 3. Overall, we found similar results for unethical behavior when using political ideology and the issue-specific measure.

A binary logistic regression using corporate activism, mean-centered political ideology, and the interaction term as independent variables and unethical behavior as the dependent variable revealed a significant interaction effect (b = -.30, SE = .10, Wald χ2(1) = 8.64, p = .003). This mirrors the finding with the entire sample.

References

Akhtar, N., Sun, J., Akhtar, M. N., & Chen, J. (2019). How attitude ambivalence from conflicting online hotel reviews affects consumers’ behavioural responses: The moderating role of dialecticism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 41, 28–40.

Anthony, C. I., & Cowley, E. (2012). Labor of lies: How lying for material rewards polarizes consumers’ outcome satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(3), 478–92.

Baskas, Harriet (2023). People are still being awful on flights, and no one really knows why? NCB News. https://www.nbcnews.com/business/travel/unruly-passenger-behavior-airline-flights-still-rampant-rcna87793. Accessed 19 Sept 2023.

Bhagwat, Y., Warren, N. L., Beck, J. T., & Watson, G. F. (2020). Corporate sociopolitical activism and firm value. Journal of Marketing, 84(5), 1–21.

Bonifield, C., & Cole, C. (2007). Affective responses to service failure: Anger, regret, and retaliatory versus conciliatory responses. Marketing Letters, 18(1), 85–99.

Centre for Retail Research (2020). Crime comparisons. https://www.retailresearch.org/crime-comparisons.html. Accessed 29 June 2022.

Delta (2008). Update: Delta ends NRA discount to annual meeting. https://news.delta.com/update-delta-ends-nra-discount-annual-meeting. Accessed 20 March 2023

Edelman (2022). The new cascade of influence. https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2022-06/2022%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Special%20Report%20The%20New%20Cascade%20of%20Influence%20FINAL.pdf.

Falk, Allie (2023). Addressing the Proliferation of Flash Mob Robberies, Loss Prevention Magazine. https://losspreventionmedia.com/flash-mob-robberies-update-and-education. Accessed 19 Sept 2023.

Ferraro, R., Kirmani, A., & Matherly, T. (2013). Look at Me! Look at Me! Conspicuous brand usage, self-brand connection, and dilution. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(4), 477–488.

Finkel, E. J., et al. (2020). Political sectarianism in America. Science, 370(6516), 533–536.

Friedman, M. (1999). Consumer boycotts: Effecting change through the marketplace and the media. Routledge.

Garg, N., & Saluja, G. (2022). A tale of two ‘Ideologies’: Differences in consumer response to brand activism. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 7(3), 325–339.

Gino, F., & Ariely, D. (2012). The dark side of creativity: Original thinkers can be more dishonest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 445–459.

Gino, F., Schweitzer, M. E., Mead, N. L., & Ariely, D. (2011). Unable to resist temptation: How self-control depletion promotes unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 191–203.

Global Strategy Group (2019). Doing Business in an Activist World. https://globalstrategygroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/GSG-2019_Doing-Business-in-an-Activist-World_Business-and-Politics.pdf.

Gneezy, U. (2005). Deception: The role of consequences. American Economic Review, 95(1), 384–394.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046.

Grégoire, Y., & Fisher, R. J. (2008). Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(2), 247–261.

Grégoire, Y., Tripp, T. M., & Legoux, R. (2009). When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 18–32.

Haidt, J. (2013). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage Books.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Huber, F., Vollhardt, K., Matthes, I., & Vogel, J. (2010). Brand misconduct: Consequences on consumer-brand relationships. Journal of Business Research, 63(11), 1113–1120.

Hydock, C., Paharia, N., & Blair, S. (2020). Should your brand pick a side? How market share determines the impact of corporate political advocacy. Journal of Marketing Research, 57(6), 1135–1151.

Jost, J. T. (2006). The End of the End of Ideology. American psychologist, 61(7), 651–670.

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–146.

Janoff-Bulman, R., Sheikh, S., & Hepp, S. (2009). Proscriptive versus prescriptive morality: Two faces of moral regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(3), 521–537.

Jung, J., & Mittal, V. (2020). Political identity and the consumer journey: A research review. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 55–73.

Jungblut, M., & Johnen, M. (2022). When brands (Don’t) take my stance: The ambiguous effectiveness of political brand communication. Communication Research, 49(8), 1092–1117.

Kang, C., Germann, F., & Grewal, R. (2016). Washing away your sins? Corporate social responsibility, corporate social irresponsibility, and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 80(2), 59–79.

Kidwell, B., Farmer, A., & Hardesty, D. M. (2013). Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 350–367.

Klostermann, J., Hydock, C., & Decker, R. (2021). The effect of corporate political advocacy on brand perception: An event study analysis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(5), 780–797.

Liaukonytė, J., Tuchman, A., & Zhu, X. (2023). Spilling the beans on political consumerism: Do social media boycotts and Buycotts translate to real sales impact? Marketing Science, 42(1), 11–25.

List, J. A., & Momeni, F. (2021). When corporate social responsibility backfires: Evidence from a natural field experiment. Management Science, 67(1), 8–21.

Mazar, N., Amir, On., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

Molho, C., Tybur, J. M., Güler, E., Balliet, D., & Hofman, W. (2017). Disgust and anger relate to different aggressive responses to moral violations. Psychological Science, 28(5), 609–619.

Monmouth University (2021). Public supports both early voting and requiring photo ID to vote. https://www.monmouth.edu/polling-institute/reports/monmouthpoll_us_062121. Accessed 29 July 2022.

Mukherjee, S., & Althuizen, N. (2020). Brand activism: Does courting controversy help or hurt a brand? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 37(4), 772–788.

National Retail Federation (2022). 2022 Retail returns rate remains flat at $816 Billion. https://nrf.com/media-center/press-releases/2022-retail-returns-rate-remains-flat-816-billion#:~:text=Of%20the%20approximately%20%24212%20billion,are%20expected%20to%20be%20fraudulent. Accessed 20 March 2023.

Newman, K. P., & Brucks, M. (2018). The influence of corporate social responsibility efforts on the moral behavior of high self-brand overlap consumers. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 28(2), 253–271.

Ordabayeva, N., & Fernandes, D. (2018). Better or different? How political ideology shapes preferences for differentiation in the social hierarchy. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(2), 227–250.

Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117–135.

Pew Research Center (2022). Public Opinion on Abortion. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/public-opinion-on-abortion/. Accessed 20 March 2023.

Repko (2022). Walmart expands abortion coverage for its employees in the wake of roe v wade decision. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/08/19/walmart-expands-abortion-coverage-for-employees-after-roe-v-wade.html. Accessed 20 March 2023.

Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2007). The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: An empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1610–1624.