Abstract

COVID-19 created a global crisis of unprecedented comprehensiveness affecting personal and professional lives of individuals worldwide. The pandemic and various governmental guidelines associated with it had numerous consequences for the workplace and the marketplace. In light of the global nature and multiplicity of the consequences of the pandemic, this study examines the impact of individual characteristics of respondents from three countries from various areas of the world: China, Israel, and the USA toward COVID-19 related business ethics decisions in three different spheres: human resources, marketing, and social responsibility. Data from 374 respondents in these three countries indicated that moral disengagement was negatively related to all of the ethical decisions presented, with national pride moderating the above. Possible implications of these findings and future research directions are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 virus created a global crisis of, perhaps, unprecedented comprehensiveness and complexity that altered both the personal and professional lives of individuals throughout the world (WHO, 2020). Worldwide, governments have adopted measures, such as stay-at-home orders and social distancing rules, which were essential to slow the spread of the disease (Walker et al., 2020). These changes impacted billons across the globe on the individual, group and societal level and necessitated weighty real-time decisions that pitted such fundamental rights as privacy and freedom of enterprise and movement against communal and societal health and safety concerns (Enste & Potthoff, 2020).

The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic touched all aspects of life, not least of which were the workplace and the marketplace (Molino et al., 2020; Moretti et al., 2020; Van der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2020) as individuals were asked to.

In the wake of the above, individuals began to speak of “the new normal” — a term used to describe a world that has been fundamentally altered. In light of the multiplicity of economic, personal and societal challenges associated with COVID-19, various societal stakeholders (i.e., government, business entities, private citizens, etc.) were faced with the task of making sense (Weick et al., 2005) of these new challenges in order to optimally respond to these challenges both from an operational perspective and a moral perspective. In light of the global nature of the pandemic, we have chosen to examine the attitudes of respondents from countries from three different areas of the world: China, Israel, and the USA toward ethical business-related decisions so as to better understand the different ways in which such decisions may be understood from a cross-cultural perspective in a world of global trade. The data for this study was collected during August 2020. In light of the multiplicity of the types of business decisions associated with COVID-19, this study presents an examination of a variety of decisions associated with three spheres relevant to the modern business organization: human resources, marketing, and social responsibility. Specifically, the study explores the impact of individual characteristics on perceptions of ethical decisions that emerged in the wake of COVID-19. Following here is a discussion of two central individual characteristics that may have particular impact on moral decision making: moral disengagement and national pride; alongside and a number of ethical business decisions associated with COVID-19.

Individual factors impacting ethical reasoning

Moral disengagement

Moral disengagement (Bandura, et al., 1991) has emerged a dominant concept in the study of ethical behavior and one of the strongest predictors of unethical work-behaviors (Claybourn, 2011; Detert et al., 2008; Harris & Comer, 2019; Moore et al., 2012). Similarly, research has clearly tied moral disengagement to harmful civic behaviors and the shirking of civic duties (Caprara et al., 2009, 2014). Specifically, within the context of the COVID-19 era, moral disengagement was seen to be inversely related with adherence to government related guidelines put into place to limit the spread of the pandemic (Alessandri et al., 2020; Schiffer et al., 2021).

Bandura et al. (1991) noted that “moral disengagement” occurs when the individual fails to regulate behavior by means of internal moral standards rather than believing that there exist adequate explanations that render that behavior legitimate. Moral disengagement emerges in order to allow individuals to relieve their sense of cognitive dissonance between principles and actions. They note that there are four different ways in which the individual may seek to disengage from the moral discomfort that they may — otherwise — experience. They can (1) decide that the behavior itself is not, necessarily, morally problematic, (2) dismiss their locus of responsibility over the action, (3) diminish the seriousness of the outcomes of their actions, and/or (4) categorize the recipient of the actions as being deserving of any detrimental effects related to the actions in question. As such, in midst of the uncertainty related to the multiplicity of novel individual, business, and societal situations that emerged in wake of COVID-19 and its assorted consequences, moral disengagement seems a particularly cogent means to assess the ethical nature of those situations. For the purposes of this work, moral disengagement will be conceived as a general tendency to disengage morally from potential ethical situations.

National pride

Bandura (1986) suggested that “the standards for moral reasoning are much more amenable to social influence than stage theories would lead one to expect” (p. 493). One central conduit of those influences are the attitudes one holds toward their national identification (Postmes et al., 2005; Tajfel, 1978; Van Bavel et al., 2020). National pride has been seen as a prerequisite of nationalism and is seen as reflecting a “love of one's country or dedicated allegiance to same” (Smith & Jarkko, 1998; p. 2) and has — in fact — been used to measure nationalism in many studies (e.g., Solt, 2011). Bonikowski (2016) suggested that nationalism has meaning for everyday decisions and actions and can best be understood as a “cognitive frame through which people apprehend social reality and construct routinized strategies of action” (p. 429); adding that national identification and its consequences may be particularly identifiable and influential in the wake of unforeseen events that are seen to threaten the group. As such, national pride can be an important prism thorough which to examine ethical decisions such as those related to COVID-19. As will be addressed later on in this paper, we believe that the degree of national pride an individual feels will be tied to their attitudes toward a variety of business ethical issues related to COVID-19.

Moral disengagement and national pride

Thus, we believe that moral disengagement is tied to the minimizing of concern regarding others in one’s national group, and national pride is tied to accentuating concern about those individuals. Bechert (2021) notes that national ride is of interest since positive attitudes toward one’s country can be expected to have a unifying effect on society. Thus, national pride might be expected to ‘temper’ moral disengagement, leading to a more nuanced understanding of and sensitivity to one’s obligations such that we hypothesize that:

-

Hypothesis 1: There will be a negative relationship between moral disengagement and perception of national pride.

COVID-19 and business ethics decisions

COVID-19 and its consequences required nearly all organizations to fundamentally reexamine — and often change — central elements of their operations (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). The focus here will be on three possible expressions of business ethical decisions associated with those changes, concerning: human resources, marketing, and social responsibility. For each, a brief overview of possible ethical decisions will be presented, followed by hypotheses of the specific aspects of the matter explored here.

COVID-19 and human resources

COVID-19 and subsequent measures put into place to stem the spread of the virus were particularly challenging for human resource management (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020; May, 2021). According to the International Labour Organization over 2·7 billion people—81% of the world’s workforce—were affected by lockdown measures (ILO, 2020), with hundreds of millions of employees transitioned into remote work, interacting with fellow employees and customers via technology. However, not all occupations afforded employees with the possibility of remote work (Barbuto et al., 2020; Savić, 2020). Among them, individuals whose services were so critical to the economy that they were called upon to continue to work — even at the expense of potentially exposing themselves to infection — and worse (Lancet, 2020). These threats speak directly to matters of the rights of employees to a safe working environment (Appelbaum, et al., 2005) and will serve as the first of the COVID-19-related Human Resources-ethical decision to be examined.

Many classes of essential employees — such as medical professionals and first responders — were celebrated as heroes by the media and the general public (e.g., Time, 2021). Others, including those working in factories, mass transit and retail were also exposed to personal danger, with much less fanfare (CDC, 2020; Middleton et al., 2020). Regardless of the reaction to the sacrifice made, it quickly became clear that in order to help reduce the risk of infection, employees were in the need of personal protective equipment (PPE) to reduce the possibility of infection (Binkley & Kemp, 2020; Nabe-Nielsen et al., 2021). With that, in the novel and fluid situation characterizing the outbreak of the pandemic, the boundaries of employee rights and employer obligations to prevent and/or control the risk associated with the pandemic were often unclear (Middleton et al., 2020) (Table 1).

Our first hypothesis addresses the question of employer provided PPE. Advocating the provision of PPE to employees reflects an acceptance of both the intrinsic personal value of employees and their rights. Thus, in light of the previous discussion regarding moral disengagement, we expect that:

-

Hypothesis 2a: Moral disengagement will be inversely related with requiring employers to supply gloves and masks to employees.

A second human resource-related ethical decision associated with COVID-19 emerged due to the social-distancing measures put into place to stem the spread of the pandemic. As a result of those measures, hundreds of millions of employees transitioned into working at home, interfacing as needed with others via technology (Barbuto, et al., 2020; Faraj et al., 2021; Savić, 2020). However, those social distancing measures also led to the closing of educational frameworks at all levels in 193 countries throughout the world, resulting in a situation in which millions of those individuals working at home were doing so while their children were at home with them (UNESCO, 2020). Not surprisingly, this situation exacerbated work-life boundary issues (Rudolph et al., 2020).

Concern with the appropriate work-life balance emerged in the 1970s, concurrent to the upsurge of female employees in increasingly diverse and senior positions at the workplace (Frame & Hartog, 2003; Lapierre et al., 2018; McDowell, 2004). By, the beginning of the twenty-first century the drive to enable employees to construct a sustainable work-life balance became an accepted measure of the ethical timbre of both individual managers at the workplace (Cowart et al., 2014; Frame & Hartog, 2003; Smith et al., 2016) and the organizations for which they worked (Alvarez-Perez, et al., 2020; Carroll et al., 2012). Indeed, recently the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2021) suggested that a central element through which businesses can express Corporate Social Responsibility is to act in a way that may “contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families, as well as of the community and society at large.”

While, questions regarding what may be the possible responsibilities of organizations regarding employee work-life balance are hardly new, COVID-19 and the closure of schools and child-care services has accentuated pressures regarding work-life balance in an exponential fashion (Miller, 2021; Wright et al., 2021). This is particularly true for employees with small children. For, while the results of Syrek et al. (2022) were inconclusive, research has overwhelmingly indicated that parents of younger children reported not only that they were more likely to be particularly (pre)occupied with their children during this period (e.g., Brom et al., 2020), but also significantly higher levels of worry, anxiety and physical exhaustion (Griffith, 2020; Shapiro et al., 2020a, 2020b; Spinelli et al., 2020).

Recognition of the unique challenges faced by parents of small children in light of COVID-19 and its consequences requires attention to and moral sensitivity toward others. The second hypothesis we propose relates to the proposition that there exists an ethical obligation on the part of employers to be particularly sensitive to the unique needs of employees with small children. Specifically, we expect that:

-

Hypothesis 2b1: There will be a negative relationship between moral disengagement and giving consideration to employees with small children.

The moderating role of parenthood on relationship of national pride and need agreeing to give consideration to employees with small children during COVID-19

One of the consequences of government actions taken to curb the spread of COVID-19 were social distancing mandates that resulted in the closure of both workplaces and educational and childcare frameworks (Lee et al., 2021). Parents reported high levels of stress and anxiety due to their need to simultaneously respond to professional and parental responsibilities (Chung et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020; Shapiro et al., 2020a, 2020b. These challenges were particularly difficult for parents of young children (Brenan, 2021; Collins et al., 2021; Ma, et al., 2020) and both researchers (Davidson et al., 2021) and organizational specialists (Randstad, 2020) called upon employers to offer special assistance to working parents struggling with the challenge of working at home while caring for children.

Self-interest theory (Jaeger, 2006; Lewin, 1991) would suggest that, in light of the palpable challenge of working from home, parents of children – themselves—will be particularly sensitive to the possibility of employers giving special consideration to parents of young children, so as to allow them to best navigate the difficulties associated with simultaneously performing their professional and parental responsibilities. Thus, we believe that:

-

Hypothesis 2b2: Parenthood will moderate the relationship of national pride and agreeing to give consideration to employees with small children.

COVID-19 and Marketing

As is wont to happen in the wake of natural or man-made disasters, a variety of marketing related ethical issues also emerged with the COVID-19 virus, including excessive pricing—more commonly known as ‘price gouging’ (Buccafusco et al., 2021; Chen, 2011; Ivanov, 2020). Snyder (2009) notes that while the precise moral argument against such rise increases is often unclear, it is widely accepted that there is something wrong about it. In the wake of COVID-19, alongside natural price increases related to disruption to supply chains (Livingston et al., 2020; Mahajan & Tomar, 2021). Both media reports and research pointed to widespread instances of a swift rise in prices, particularly regarding pandemic related items such as hand sanitizers, disinfectants, and disposable respiratory protection masks (Giosa, 2020; Kianzad, 2020; National Law Review, 2021; Mackenzie et al., 2020). A price is excessive (or “gouged”) when “it has no reasonable relation to the economic value of the product supplied” (e.g., European Union, 2021).

Buccafusco et al. (2021) suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique opportunity to examine price gouging in “real-time’ – in the midst of the uncertainty and fears associated with a global pandemic with a multiplicity of economic, physical, psychological and societal challenges. Price-gouging will serve here as the focus of our discussion of ethical marketing decisions associated with COVID-19. A growing empirical literature seeks to understand when and why such societal norms regarding price fairness emerge (Kahneman, et al., 1986; Richards et al., 2016; Trujillo et al., 2020). Kahneman et al. (1986) proposed a theory regarding fairness called the dual entitlement theory that suggests that both consumers and providers are entitled to a final price according to some function of the rights of the buyers for a fair price and the rights of providers for a fair profit. Resulting from the above, there ensues a moral pressure to curb price rises in times of crisis.

However, a question remains what occurs when the potential profit of local providers does not come at a potential cost to local consumers, such as when a local firm raises prices for foreign consumers. In light of the potential impact of national pride on the sense of ‘in-group vs. out-group’ rights, we believe that a strong sense of national pride helps shapes norms toward price-gouging toward foreign consumers. Specifically, we believe that national pride will led to individuals distinguishing between consumers in their own nation and those elsewhere, leading to a situation in which those with a greater sense of national pride will exhibit less sensitivity to price gouging toward foreign consumers.

-

Hypothesis 2c: There will be positive relationship between moral disengagement and national favoritism for gouging masks leading to a greater tolerance for price –gouging of toward foreign consumers.

COVID-19 and societal issues

One of the first insights regarding the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus was the particular threat the pandemic posed for the elderly and other populations with health vulnerabilities (Daoust, 2020; Richardson et al., 2020). This led to the publication of directives for these individuals to stay at home, stay away from other people and avoid discretionary outings (CDC, 2020; Cohen, 2020). Following soon, retails stores throughout the world announced special dedicated shopping hours for the elderly (Kassraie, 2020; Perper, 2020). These efforts were portrayed by many organizations—and generally received by the public – as an example of good organizational citizenship aimed to aid society on the whole (Garcia-Sanchez & Garcia-Sanchez, 2020; Koch, 2021; Schwartz & Kay, 2020).

An example of this concern can be seen in the decision by the Albertson Companies that comprise more than 2,200 supermarkets operating under 20 banners in the USA (Albertsons, 2020).

We are sensitive to the fact that everyone wants to make sure they have the items they need, and we also know that everyone wants their neighbors to stay safe and healthy, too….We are asking our customers to respect these special hours for those who are most at risk in our communities. We thank our customers in advance for their compassion and understanding toward their neighbors and friends, and in helping us maintain this temporary operations guideline.

The special hours put into place are seen as an ethically inspired gesture aimed to contribute to the surrounding community, and greater society – even at the expense of possible organizational and customer inconvenience. Thus, we believe that:

-

Hypothesis 2d:: There will be a negative relationship between moral disengagement and providing special shopping hours for the elderly etc. – even at the cost of less profit.

National Pride and COVID-19 Related Business Ethical Decisions

As noted, there is reason to believe that national pride is a significant prism through which the individual may view their ethical obligations. While some findings (e.g., Rupar et al., 2021) pointed to the limitations of national group feelings as a mechanism for eliciting compliance to COVID-19 related guidelines (e.g., mask-wearing), most research has found such group feelings associated with mutual cooperation and adherence to norms (Buchan et al., 2011; De Cremer & Van Vugt, 1999), motivation to help other members of their group (Ellemers et al., 1999; Levine et al., 2005), in-group economic favoritism related to trade and employment (Brewer, 1993; Diaz & Mountz, 2020; Shayo, 2009, 2020) and actions that advance group public health in the current pandemic (Owen et al., 2020; Van Bavel et al., 2020).

Differences in the timing and severity of COVID-19 both within and across national boundaries led to wide-spread border closings as countries sought to limit the spread of the pandemic within their own borders (Leigh, 2020). While Stiglitz et al. (2020) found otherwise, research has almost been unanimously pointed to the fact that the physical closing of borders and worry surrounding the influx of potentially ill foreign nationals into countries has exacerbated both feelings of in-group/out-group and reservations, if not fear, regarding the latter (Bieber, 2020; Vogel, 2020).

Accordingly, both Van Barneveld et al. (2020) and Goode et al. (2022) present compelling arguments why the upheavals associated with the COVID-19 pandemic will likely both crystallize national feelings and make it a more potent force in everyday life. In light of the above, we believe that:

-

Hypothesis 3a:: There will be a positive relationship between national pride and requiring employers to supply gloves and masks to employees.

-

Hypothesis 3b: There will be a positive relationship between national pride and giving consideration to employees with small children.

-

Hypothesis 3c: There will be a positive relationship between national pride and national favoritism concerning gouging prices for masks for foreign consumers.

-

Hypothesis 3d: There will be a positive relationship between national pride and providing special shopping hours for the elderly etc. – even at the cost of less profit.

The mediating role of national pride in the relationship between moral disengagement and the four ethical decisions

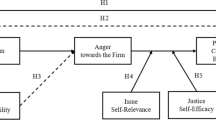

We expect that national pride will mediate relationships between moral disengagement and the various ethical decisions addressed here. Before examining those ethical decisions and the possible mediating role that national pride may play with regard to those decisions, we will point out that as our data is correlational by nature, the mediation analysis is being used to examine the interrelationship among various variables, but cannot — of course — speak to causality (Fiedler, 2011; Wiedermann & von Eye, 2015). Here, we expect that, though, moral disengagement will be inversely related to being sensitive to various ethical decisions, for those decisions involving individuals from one’s own group, national pride will emerge as a potent force and mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and ethical decisions in which national-identity plays a role and be associated with ethical sensitivity (Fig. 1).

-

Hypothesis 4a:: National pride will mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and requiring employers to supply gloves and masks to employees.

-

Hypothesis 4b:: National pride will mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and giving consideration to employees with small children (Fig. 2).

-

Hypothesis 4c:: National pride will mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and national favoritism for gouging masks.

-

Hypothesis 4d:: National pride will mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and providing special shopping hours for the elderly etc. — even at the cost of less profit.

Materials and methods

Sample and procedure

Three hundred seventy-four participants from China (N = 162), USA (N = 108), and Israel (N = 104) completed a questionnaire online.Footnote 1 The data was collected during August 2020. Participation was based on a referral sample (Voicu & Babonea, 2011). The age range was 18–50 + (median age range was 23–29). Fifty-one percent of the respondents were male; with nearly two thirds (63.4%) of the sample being married or in a domestic partnership, 33% single and the remaining 3.4% were either divorced or widowed and roughly half of the sample did not have children (see Fig. 3). Education levels are shown in Fig. 4. Nearly half of the participants (47%) identified as Jewish, 1.9% Christian, 1.4% as Buddhist and Moslem (each), 0.5% Hindu and the remaining as ‘Agnostic’ (7.1%) or ‘Spiritual’ or ‘Other’ (2.4% each). About 35.9% of the participants did not wish to identify themselves with a religion. Nearly three-quarters of the respondents (71.7%) are employed by others, 9.6% self-employed, 5.9% unemployed due to COVID-19, with the remaining respondents saying that they were unemployed (9.6%) or already retired (3.5%) prior to the pandemic. Finally, regarding income, the average and median answer was — “about the same as the average”. Data was collected in compliance with ethical standards, and anonymity was assured.

Measures

Moral disengagement

Propensity to moral disengage was assessed using the 8-item questionnaire developed by Moore et al., (2012). The items were adapted to Hebrew and Chinese by means of the forward–backward translation method. Respondents were asked to rate each item on a 7-point scale—ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Sample items included “Taking something without the owner’s permission is okay as long as you’re just borrowing it” and “Taking personal credit for ideas that were not your own is no big deal.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.89.

National pride

Following other studies (e.g., Miller-Idriss & Rothenberg, 2012), we assessed national pride using one item. “How much do you agree with the following: “I am proud to be (American/Chinese/Israeli).” Respondents were asked to rate this item on a 7-point scale—ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree).

Dependent variable: ethical decisions

We asked participants a variety of items regarding ethical decisions related to COVID -19 and its consequences. The items followed the question: “How much do you agree with the following:” Sample items were “During a pandemic like Corona, retail stores should supply workers with gloves and face-masks for their protection at work..” and “During a pandemic like Corona, retail stores should have special hours for populations at risk (like the elderly or sick)—even if it may adversely affect revenue.” The national favoritism variable was comprised of the difference between gouging individuals of foreigners and the participant's nationality. Items were “In January, an individual expected that the Corona virus would result in a shortage of products such as face-masks, gloves and disinfecting gel. Thus they bought up a lot of the above. Two months later, when the Corona virus hit and people were told to stay at home they sold the above products to foreigners—or—American/Chinese/Israeli customers at a price 25% over its usual cost.”

Demographic data

Participants were asked to state their age, gender, education level (from 1 = less than 12 years, to 5 = Master’s degree or above), religiosity (from 1 = secular, to 4 = ultra-Orthodox), occupation status (employed, unemployed due to COVID-19, unemployed prior to COVID-19, I own business, retired), religion, personal status and number of children, and level of income (from 1 = Much lower than the average to 5 = Much higher than the average).

Control variables

Financial stress

We assessed financial stress during COVID-19 using one item “The outbreak of the corona and its consequences have adversely affected my financial security”. Respondents were asked to rate this question on a 7-point scale—ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree).

Social desirability

As suggested by Tan et al., (2021), we deemed it important to assess social desirability using the 10-item Crowne-Marlowe Social Desirability Scale. The items followed the question: “Please answer as to whether you have ever done this:” Sample items were “There have been occasions when I took advantage of someone.” and “At times I have really insisted on having things my own way.” Respondents were asked to give a Yes/No answer to these questions.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations are shown in Table 2.

Before hypotheses testing, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the continuous scale of moral disengagement using SPSS (Version 25) to test the discriminant validity. Total variance explained was 56% and the principal component analysis extracted only one component (the solution could not be rotated). The Eigen value of the 10 items ranged from 0.7 to 0.83.

Main analysis hypotheses test

To test our hypotheses, we used linear regression (for hypotheses 1 and 2a, 2b1,2c, 2d), Hayes' (2017) procedure to test for regression mediation using SPSS macro PROCESS 3.2 model 4 (for hypotheses 3 and 4) and model 14 (for Hypothesis 2b2). To reduce nonessential multicollinearity concerns (Enders & Tofighi, 2007), the independent variables were mean-centered before computing product terms. All results were controlled for financial stress during COVID-19 and social desirability.

Hypothesis 1 proposed that there will be an inverse relationship between moral disengagement and national pride. Results support hypothesis 1 and show a significant negative relationship (b = − 0.16, t(374) = − 2.34, p = 0.02).

Hypotheses 2a-d proposed that there will be a negative relationship between moral disengagement and ethical decisions during COVID-19 (i.e., require employers to supply gloves and masks to employees (H2a); giving consideration to employees with small children (H2b1); national favoritism for gouging masks (H2c); and providing special shopping hours for the elderly etc. — even at the cost of less profit (H2d)).

Results support hypothesis 2a and show that the relation was negative and significant (b = − 18, t(374) = − 2.71, p < 0.01). Results for hypothesis 2b1 show that the relationship was negative but not significant (b = − 0.11, t(374) = − 1.62, p = 0.10). Results for hypothesis 2c show that the relationship was negative, but not significant (b = − 0.11, t(374) = − 1.89, p = 0.06). Results for hypothesis 2d show a negative non-significant relation (b = − 0.08, t(374) = 1.08, p = 0.28).

Hypothesis 2b2 proposed a moderating role of parenthood on the relationship of moral disengagement and giving consideration to employees with small children. Results supported this hypothesis and indicated a significant interaction between national pride and parenthood on giving consideration to employees with small children (Table 3). The mediation moderation model summary was significant (F[6, 367] = 3.7, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.0.6) and the addition of the interaction was a significant change to the model (F[6, 938] = 6.64, p = 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.02). The slope for national pride was significant (b = 0.19, t[374] = 3.29, p = 0.001), the slope for parenthood was not significant (b = 0.003, t(374) = 0.16, p = 0.99), and the slope for the interaction was significant (b = 0.29, t[374] = 2.58, p = 0.01).

The interaction was plotted and presented in Fig. 5. Explicitly, individuals with high national pride who have children showed higher agreement for giving consideration to employees with small children. Individuals with low levels of national pride who have children showed low agreement for giving consideration to employees with small children. As for individuals with no children, there was no significant difference in agreement of giving said consideration between those with low and those with high levels of national pride.

Hypotheses 3a-d proposed that national pride will be positively related to the four ethical decisions (i.e., require employers to supply gloves and masks to employees (H3a); giving consideration to employees with small children (H3b); national favoritism of gouging masks (H3c); and providing special shopping hours for the elderly etc. — even at the cost of less profit) (H3d)).

Results show that for H3a the relationship was indeed positive and significant (b = 0.39, t(374) = 8.51 p < 0.01). For H3b, the relationship was positive and significant (b = 0.26, t(374) = 5.37, p < 0.01). For H3c, the relationship was positive and significant (b = 0.11, t(374) = 2.58, p = 0.01). Finally, for H3d, the relationship was positive and significant (b = 0.16, t(374) = 2.9, p < 0.01).

Hypotheses 4a-d proposed that national pride will mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and the four ethical decisions during COVID-19 (i.e., require employers to supply gloves and masks to employees (H4a); giving consideration to employees with small children (H4b); national favoritism of gouging masks (H4c); and providing special shopping hours for the elderly etc. — even at the cost of less profit (H4d)).

Results support hypothesis 4a. National pride fully mediates the relation of moral disengagement and supplying gloves and masks (indirect effect = − 0.06 SE = 0.032, 95% CI[− 0.13, − 0.007]). Results support hypothesis 4b. National pride fully mediates the relation of moral disengagement and giving consideration to employees with small children (indirect effect = − 0.03 SE = 0.02, 95% CI[− 0.07, − 0.002]). Results do not support the mediation of national pride for the relationship of moral disengagement and national favoritism (H4c) (indirect effect = − 0.02 SE = 0.01, 95% CI[− 0.05,0.0001]). Results support hypothesis 4d. National pride fully mediates the relation of moral disengagement and giving special hours to the elderly (indirect effect = − 0.06 SE = 0.032, 95% CI[− 0.13, − 0.007]). Results of hypotheses 1–4 are shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

Discussion

In light of the to the global and multifaceted nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study sets out to examine the possible relationship between moral disengagement (Bandura, 1986) and four different business ethical decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic from a cross-cultural perspective. Due to the nature of the pandemic, countries throughout the world implemented strict restrictions on interpersonal contact and closed their borders in order to gain control over the swiftly spreading and deadly disease. Border closures of this type could but accentuate both the perception of those outside one’s nation as posing an external threat and organic solidarity and group cohesiveness within the nation (Allan, 2005; Durkheim, 2014; Forsyth, 2009). As such, we felt it important to introduce national pride into our models in order to address the possible impact of the perception of group cohesion on ethical decisions. In line with previous research (Castano, 2008) this study also found that moral disengagement is negatively related to national pride. We utilized the pandemic period in order to examine individual moral thinking through the presentation of a series of possible pandemic-related ethical decisions related to three foci of business activities: human resources, marketing, and societal responsibility.

We found that moral disengagement was negatively related to all of the ethical decisions presented. That is to say, as expected, individuals with higher levels of moral disengagement exhibited less agreement with the ethical imperative associated with possible business actions that could help others better navigate the uncertainty and challenges associated with the outbreak of the pandemic. Regarding HR decisions, individuals with lower moral disengagement were more likely to agree that employers should supply employees with gloves and masks during the pandemic, should give consideration for employees with small children.

As predicated, national pride moderated support for the decision whether employers should give special consideration to employees with small children in wake of the complexities of work and home life associated with COVID-19. Increased national pride was associated with increased support for special consideration among both those with and without children. With that, an unusual pattern emerged regarding the relationship between national pride and special consideration for those with children. For among those with low national pride, those with children expressed less support for special consideration than those who did not have children. That pattern was reversed among individuals with high levels of national pride. In both cases, those without children expressed moderate support for such special consideration for parents of children.

The results reflect the complexity of the relationship between “family responsive” human resource policies (Kamerman & Kahn, 1987) and employee attitudes toward those policies. A number of studies found that the provision of family oriented support was tied to a variety of positive organizational outcomes (i.e., affective commitments, job satisfaction etc.), regardless as to whether the individual did — or even could — benefit from such support (Butts et al., 2013; Garg &Agrawal, 2020; Grover & Crooker, 1995).

Thus, it may not necessarily be surprising that parental status is not the sole arbitrator of support for a “family responsive” policy such as the one proposed here. The relative lack of support for such a policy among parents with low national pride may reflect a feeling among those individuals that having children is a completely personal choice and “if they can manage” then so can other individuals who have chosen to have children. However, in the high national pride situation, it is possible that having children is seen as having communal (national) significance and importance. Reproduction is a sexual expression of a social contract and fertility and the children associated with it exists as a natural resource in a nation to strengthen its numbers and allow for its continuity and growth (Maxwell, 2016; Mole, 2016; Pateman, 2016). As such, their children and those of others, are deserving of the greatest consideration possible.

Regarding the marketing decision, individuals with higher moral disengagement exhibited national favoritism associated with the gouging of masks to foreigners. Cabral and Xu (2021) note that times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, often heighten a tension between price surges resulting from a natural market efficiency and concerns for fairness. With that, they found that certain factors — such as the desire of a seller to preserve their reputation — may mitigate a tendency to take advantage of market conditions and gouge prices in times of crisis. In the situation examined here, national pride emerges as such a factor. The particular salience of nationalistic feelings in the wake of COVID-19 has been borne out by a number of empirical studies done since its advent (Hartman et al., 2021; Perry et al., 2021; Su & Shen, 2021).

Thus, it is not surprising that while it was not necessarily seen as unacceptable to gouge prices when dealing with foreign consumers among those for whom national pride was important, it was unacceptable to do so with customers from one’s own group. The lack of respect for the needs of others based on their group identity is an example of what Zwolinski (2008) termed the lack of respect of the ‘personhood’ of the exploited individual. Thus, as the moral disengagement literature suggests individuals may disconnect from the wrong associated with moral misgivings associated, generally, with sharp price increases during crisis periods. Clearly, when accepting differential pricing of this type, it is not simply market forces at play here, but a (dis)regard of the individual due to their identity. As such, it seems that nationalistic feelings can be added to the growing list of factors that may shape both behaviors and attitudes behind price gouging that was initiated by the classic Kahneman et al. (1987) research on the matter.

Syropoulos and Markowitz (2021) noted that the COVID-19 pandemic created what they termed an “unprecedented collective action problem” in which individuals must make a variety of decisions that influence both their own well-being and the health of those around them.” As noted, retail establishments — such as the Albertson Companies — found themselves at the forefront of the fight against a global pandemic and as — potential — guardians of the health of their most vulnerable customers. As expected, we found that individuals with lower moral disengagement were more likely to believe that store owners should provide special shopping hours for the elderly — even at the cost of less profit. This finding offers support for finding regarding matters that may impact self-sacrificial actions (Crone & Laham, 2015). Once again, national pride mediates the aforementioned relationship with those with more national pride feeling most strongly about this matter.

Conclusions

This study offers a variety of contributions. First, the study points to the utility of moral disengagement as a possible explicator of business-related ethical decisions — even under unusual conditions such as a global pandemic. In addition to the above, the data highlights the potential impact of national pride as a mechanism that acts on such decisions. This last matter has both theoretical and practical implications. First, from a theoretical perspective, this result concerning national pride contributes to the literature regarding factors that may mold fairness decisions (e.g., Kahneman et al., 1986). From a practical perspective, the data indicate the possible — and often unexpected or undesired — impact of both intentional efforts to create national pride and possible similar outcomes of policy decisions such as border closings. As such, this study is a test of known variables in new uncharted water, offering a glimpse of what may happen when individuals face novel ethical decisions within a novel reality. Another practical contribution relates to the global nature of the pandemic and its possible impact on decision making. As the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, we live in a global reality in which contact among individuals from around the globe is inevitable. To best navigate that world it behooves both leaders and lay-people to better understand how others with whom they come into contact may view business decisions, particularly those guided by personal values and preferences.

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. First, the data were gleaned using a cross-sectional design, which hinders the opportunity to draw causal conclusions about relationships between the variables. Future studies should overcome this limitation by pursuing a longitudinal or experimental design.

Second, common-method bias may have been present due to self-report data (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Still, though the implications of common-method bias are debated and overstated (Spector, 2006), future research should use data from additional sources.

In the context of the above, it is important to note that no differences were found among the three countries with respect to the model we tested. With that, we recommend further investigation into the differences between countries when moral disengagement is concerned, with the expectation that cultural effects can influence ethical decisions. It is also worthwhile to examine moral disengagement’s relationship to additional ethical decisions with other foci, in order to deepen the understanding of this phenomenon. Finally, as Kay (2018) has shown, there is reason to assume that cohort-related experiences may impact an individual’s ethical attitudes. Generational differences may be a particularly salient matter when connected to an event such as the recent global pandemic that has led to a multiplicity of disruptions and changes in the lives of individuals, organizations, and whole nations. Thus, it may be interesting to examine how these recent events may impact business related ethical attitudes among younger individuals who came of age around parallel to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Notes

Data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Allan, K. (2005). Explorations in classical sociological theory: Seeing the social world. Pine Forge Press.

Albertsons (2020). https://www.albertsonscompanies.com/newsroom/shopping-hours-for-vulnerable-customers.html

Alessandri, G., Filosa, L., Tisak, M. S., Crocetti, E., Crea, G., & Avanzi, L. (2020). Moral disengagement and generalized social trust as mediators and moderators of rule-respecting behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2102.

Alvarez-Perez, M. D., Carballo-Penela, A., & Rivera-Torres, P. (2020). Work-life balance and corporate social responsibility: The evaluation of gender differences on the relationship between family-friendly psychological climate and altruistic behaviors at work. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(6), 2777–2792.

Appelbaum, S. H., Deguire, K. J., & Lay, M. (2005). The relationship of ethical climate to deviant workplace behaviour. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society., 5(4), 43–55.

Bandura, A., Kurtines, W. M., & Gewirtz, J. L. (1991). Handbook of moral behavior and development. Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development, 1, 45–103.

Barbuto, A., Gilliland, A., Peebles, R., Rossi, N., & Shrout, T. (2020). Telecommuting: Smarter Workplaces Spring. 2020. The Ohio State University.

Bechert, I. (2021). Of pride and prejudice—A cross-national exploration of atheists’ National Pride. Religions, 12(8), 648.

Bieber, F. (2020). Global nationalism in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nationalities Papers, 1–13.

Binkley, C. E., & Kemp, D. S. (2020). Ethical rationing of personal protective equipment to minimize moral residue during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 230(6), 1111–1113.

Bonikowski, B. (2016). Nationalism in settled times. Annual Review of Sociology, 42, 427–449.

Brenan, M. (11 March 2021). Amid Pandemic, 79% of K-12 Parents Support In-Person School https://news.gallup.com/poll/336173/amid-pandemic-parents-support-person-school.aspx

Brewer, T. L. (1993). Government policies, market imperfections, and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(1), 101–120.

Brom, C., Lukavský, J., Greger, D., Hannemann, T., Straková, J., & Švaříček, R. (2020, July). Mandatory home education during the COVID-19 lockdown in the Czech Republic: A rapid survey of 1st-9th graders' parents. In Frontiers in Education, 5, 103.s.

Buccafusco, J., Hemel, D. J., Talley, E. L. (2021). Price gouging in a pandemic. SSRN Electronic Journal https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3758620

Buchan, N. R., Brewer, M. B., Grimalda, G., Wilson, R. K., Fatas, E., & Foddy, M. (2011). Global social identity and global cooperation. Psychological Science, 22(6), 821–828.

Butts, M. M., Casper, W. J., & Yang, T. S. (2013). How important are work–family support policies? A meta-analytic investigation of their effects on employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 1.

Cabral, L., & Xu, L. (2021). Seller reputation and price gouging: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic Inquiry, 59(3), 867–879.

CDC (27 March 2020). Severe outcomes among patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) — United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr /volumes /69/wr/mm6912e2.htm

Caprara, G. V., Fida, R., Vecchione, M., Tramontano, C., & Barbaranelli, C. (2009). Assessing civic moral disengagement: Dimensionality and construct validity. Personality and Individual Differences., 47, 504–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.027

Caprara, G. V., Tisak, M. S., Alessandri, G., Fontaine, R. G., Fida, R., & Paciello, M. (2014). The contribution of moral disengagement in mediating individual tendencies toward aggression and violence. Developmental Psychology, 50, 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034488

Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183–187.

Carroll, A. B., Lipartito, K. J., Post, J. E., & Werhane, P. H. (2012). Corporate responsibility: The American Experience. Cambridge University Press.

Castano, E. (2008). On the perils of glorifying the in-group: Intergroup violence, in-group glorification, and moral disengagement. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 154–170.

Chen, A. (2011). A market-based and synthesised approach to controlling price gouging. International Journal Private Law, 4(1), 128–142.

Chung, S. K. G., Chan, X. W., Lanier, P., & Wong, P. (2020). Associations between work-family balance, parenting stress, and marital conflicts during COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore.

Claybourn, M. (2011). Relationships between moral disengagement, work characteristics and workplace harassment. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(2), 283–301.

Cluver, L., Lachman, J. M., Sherr, L., Wessels, I., Krug, E., Rakotomalala, S., & McDonald, K. (2020). Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet, 395, 10231.

Cohen, E. (March 7, 2020). New CDC guidance says older adults should 'stay at home as much as possible' due to coronavirus. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/06/health/coronavirus-older-people-social-distancing/index.html. Accessed 28 June 2020.

Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., & Scarborough, W. J. (2021). COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work & Organization, 28, 101–112.

Cowart, T., Gilley, A., Avery, S., Barber, A., & Gilley, J. W. (2014). Ethical leaders: Trust, work-life balance, and treating individuals as unique. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 11(3), 70.

Crone, D. L., & Laham, S. M. (2015). Multiple moral foundations predict responses to sacrificial dilemmas. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 60–65.

Daoust, J. F. (2020). Elderly people and responses to COVID-19 in 27 Countries. PLoS ONE, 15(7), e0235590.

Davidson, B., Schmidt, E., Mallar, C., Mahmoud, F., Rothenberg, W., Hernandez, J., ... & Natale, R. (2021). Risk and resilience of well-being in caregivers of young children in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(2), 305-313

De Cremer, D., & Van Vugt, M. (1999). Social identification effects in social dilemmas: A transformation of motives. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(7), 871–893.

Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 374.

Diaz, I. I., & Mountz, A. (2020). Intensifying fissures: Geopolitics, nationalism, militarism, and the US response to the novel coronavirus. Geopolitics, 25(5), 1037–1044.

Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 284–289.

Durkheim, E. (2014). The division of labor in society. Simon and Schuster.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (Eds.). (1999). Social Identity: Context, Commitment, Content. Blackwell.

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121.

Enste, D., & Potthoff, J. (2020). The business ethics of the Corona crisis: A critical analysis of political measures, economic consequences, and ethical challenges (No. 55/2020). IW-Report.

European Union. (2021). Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). https://europa.eu/european-union/law/treaties. Accessed August 26 2021).

Faraj, S., Renno, W., & Bhardwaj, A. (2021). Unto the breach: What the COVID-19 pandemic exposes about digitalization. Information and Organization, 31(1), 100337.

Fiedler, K. (2011). Voodoo correlations are everywhere—Not only in neuroscience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(2), 163–171.

Forsyth, D. R. (2009). Group Dynamics. Wadsworth.

Frame, P., & Hartog, M. (2003). From rhetoric to reality. Into the swamp of ethical practice: implementing work-life balance. Business Ethics: A European Review, 12(4), 358–368.

Garcia-Sanchez, I. M., & Garcia-Sanchez, A. (2020). Corporate social responsibility during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 126.

Garg, S. & Agrawal, P. (2020). Family-friendly practices in the organization: A citation analysis. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy., 40(7/8), 559–573.

Giosa, P. A. (2020). Interim measures: a remedy to deal with price gouging in the time of COVID-19.

Goode, J. P., Stroup, D. R., & Gaufman, E. (2022). Everyday nationalism in unsettled times: In search of normality during pandemic. Nationalities Papers, 50(1), 61–85.

Griffith, A. K. (2020). Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00172-2

Grover, S. L., & Crooker, K. J. (1995). Who appreciates family-responsive human resource policies: The impact of family-friendly policies on the organizational attachment of parents and non-parents. Personnel Psychology, 48(2), 271–288.

Hartman, T. K., Stocks, T. V., McKay, R., Gibson-Miller, J., Levita, L., Martinez, A. P., & Bentall, R. P. (2021). The authoritarian dynamic during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550620978023.

Harris, H. & Comer, D. (Eds.), (2019). The Next Phase of Business Ethics: Celebrating 20 Years of REIO. Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations, 21, 47–63. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1529-209620190000021007

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach. Guilford Publications.

Ivanov, D. (2020) Predicting the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains: A simulation-based analysis on the Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) Case, 136 Transp. Res. Part E: Logistics & Transportation Review, 1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1366554520304300

ILO (2020). https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_741358/lang-en/lang--en/index.htm

Jaeger, M. M. (2006). What makes people support public responsibility for welfare provision: Self-interest or political ideology? A Longitudinal Approach. Acta Sociologica, 49(3), 321–338.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. American Economic Review, 76(4), 728–741.

Kamerman, S. B., & Kahn, A. J. (1987). The responsive workplace: Employers and a changing tabor force. Columbia University Press.

Kassraie, A. (22 April 2020). Supermarkets offer special hours for older shoppers. https://www.aarp.org/home-family/your-home/info-2020/coronavirus-supermarkets.html.

Kay, A. (2019). The future of business ethics and the individual decision maker. In M. Schwartz,

Kianzad, B. (2020). The Giant Awakens-Law and Economics of Excessive Pricing & COVID-19 Crisis. Available at SSRN 3706793.

Koch, J. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer Behavior in Retail Stores.

Lancet, T. (2020). The plight of essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet, 395(10237), 1587.

Lapierre, L. M., Li, Y., Kwan, H. K., Greenhaus, J. H., DiRenzo, M. S., & Shao, P. (2018). A meta-analysis of the antecedents of work–family enrichment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(4), 385–401.

Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., Chang, O. D., & Downing, K. M. (2021). Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children and Youth Services Review, 122, 105585.

Leigh, G. (18 March 2020). Does closing borders really stop the spread of Coronavirus? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/gabrielleigh/2020/03/18/does-closing-borders-really-stop-the-spread-of-coronavirus/?sh=40f2804077c8

Lewin, L. (1991). Self-interest and Public Interest in Western Politics. OUP Oxford.

Levine, M., Prosser, A., Evans, D., & Reicher, S. (2005). Identity and emergency intervention: How social group membership and inclusiveness of group boundaries shape helping behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(4), 443–453.

Livingston, E., Desai, A., & Berkwits, M. (2020). Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA, 323(19), 1912–1914.

Ma, S., Sun, Z., & Xue, H. (2020). Childcare needs and parents’ labor supply: Evidence from the COVID-19 Lockdown. Available at SSRN 3630842.

McDowell, L. (2004). Work, workfare, work/life balance and an ethic of care. Progress in Human Geography, 28(2), 145–163.

Mackenzie, R., Mantine, M., Wang, D. & Seuster, M. (30 June 2020). Global risks of charging unfair and excessive prices in times of COVID-19. https://www.reedsmith.com/en/perspectives/2020/06/global-risks-of-charging-unfair-and-excessive-prices-in-times-of-covid19.

Mahajan, K., & Tomar, S. (2021). COVID-19 and supply chain disruption: Evidence from food markets in India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 103(1), 35–52.

Maxwell, A. (2016). Nationalism and Sexuality. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, 1–4.

May, W. M. L. (2021). The impacts of Covid-19 on foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 10(2), 357–370.

Middleton, J., Reintjes, R., & Lopes, H. (2020). Meat plants—A new front line in the covid-19 pandemic. bmj, 370–382..

Miller, K. E. (2021). The ethics of care and academic motherhood amid COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization, 28, 260–265.

Miller-Idriss, C., & Rothenberg, B. (2012). Ambivalence, pride and shame: Conceptualisations of German nationhood. Nations and Nationalism, 18(1), 132–155.

Mole, R. C. (2016). Nationalism and homophobia in Central and Eastern Europe. In The EU Enlargement and Gay Politics (pp. 99–121). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Molino, M., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Manuti, A., Giancaspro, M. L., Russo, V., ... & Cortese, C. G. (2020). Wellbeing costs of technology use during Covid-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability, 12(15), 5911

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Klebe Treviño, L., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 1–48.

Moretti, A., Menna, F., Aulicino, M., Paoletta, M., Liguori, S., & Iolascon, G. (2020). Characterization of home working population during COVID-19 emergency: A cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6284.

Nabe-Nielsen, K., Nilsson, C. J., Juul-Madsen, M., Bredal, C., Hansen, L. O. P., & Hansen, Å. M. (2021). COVID-19 risk management at the workplace, fear of infection and fear of transmission of infection among frontline employees. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 78(4), 248–254.

National Law Review (13 January 2021). Price Gouging Weekly Round Up - January 11, 2021. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/price-gouging-weekly-round-january-11-2021.

Owen, N., Healy, G. N., Dempsey, P. C., Salmon, J., Timperio, A., Clark, B. K., ... & Dunstan, D. W. (2020). Sedentary behavior and public health: Integrating the evidence and identifying potential solutions. Annual review of public health, 41, 265-287

Pateman, C. (2016). Sexual contract. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, 1–3.

Perper, R. (19 March 2020). Here are all the major grocery-store chains around the world running special hours for the elderly and vulnerable to prevent the coronavirus spread. https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-stores-special-hours-elderly-vulnerable-list-2020-3.

Perry, S. L., Whitehead, A. L., & Grubbs, J. B. (2021). Prejudice and pandemic in the promised land: How White Christian nationalism shapes Americans’ racist and xenophobic views of COVID-19. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(5), 759–772.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Swaab, R. I. (2005). Social influence in small groups: An interactive model of social identity formation. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 1–42.

Randstad (18 September 2020). How to accommodate workers with kids during COVID-19 September 18th. https://www.randstad.ca/employers/workplace-insights/talent-management/how-to-support-parents-working-from-home-during-covid-19/.

Richards, T. J., Liaukonyte, J., & Streletskaya, N. A. (2016). Personalized pricing and price fairness. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 44, 138–153.

Richardson, S. J., Carroll, C. B., Close, J., Gordon, A. L., O’Brien, J., Quinn, T. J., ... & Witham, M. D. (2020). Research with older people in a world with COVID-19: Identification of current and future priorities, challenges and opportunities. Age and Ageing, 49(6), 901-906

Rudolph, C., Allan, B., Clark, M., Hertel, G., Hirschi, A., Kunze, F., Shockley, K., Shoss, M., Sonnentag, S. & Zacher, H. (2020). Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/k8us2

Rupar, M., Jamróz-Dolińska, K., Kołeczek, M., & Sekerdej, M. (2021). Is patriotism helpful to fight the crisis? The role of constructive patriotism, conventional patriotism, and glorification amid the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Social Psychology, 51(6), 862–877.

Savić, D. (2020). COVID-19 and work from home: Digital transformation of the workforce. Grey Journal (TGJ), 16(2), 101–104.

Schiffer, A. A., O’Dea, C. J., & Saucier, D. A. (2021). Moral decision-making and support for safety procedures amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 175, 110714.

Schwartz, M. and Kay, A. (2020). Business ethics and coronavirus. In Proceedings of the 27th International Vincentian Business Ethics Conference. https://drive.google.com/file/d/11icV_OuoIXZCmfYuliW9YfSK0EcojMXr/view. 72–73.

Shapiro, A. F., Gottman, J. M., & Fink, B. C. (2020). Father’s involvement when bringing baby home: Efficacy testing of a couple-focused transition to parenthood intervention for promoting father involvement. Psychological Reports, 123(3), 806–824.

Shapiro, M. O., Gros, D. F., & McCabe, R. E. (2020). Intolerance of uncertainty and social anxiety while utilizing a hybrid approach to symptom assessment. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 13(3), 189–202.

Shayo, M. (2009). A model of social identity with an application to political economy: Nation, class, and redistribution. American Political Science Review, 103(2), 147–174.

Shayo, M. (2020). Social identity and economic policy. Annual Review of Economics, 12.

Smith, T. W., & Jarkko, L. (1998). National pride: A cross-national analysis. National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago.

Smith, K. T., Smith, L. M., & Brower, T. R. (2016). How work-life balance, job performance, and ethics connect: Perspectives of current and future accountants. In Research on Professional Responsibility and Ethics in Accounting. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Snyder, J. (2009). What’s the matter with price gouging? Business Ethics Quarterly, 19(2), 275–293.

Solt, F. (2011). Diversionary nationalism: Economic inequality and the formation of national pride. The Journal of Politics, 73(3), 821–830.

Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232.

Spinelli, M., Lionetti, F., Pastore, M., & Fasolo, M. (2020). Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1713.

Stiglitz, J. E., Shiller, R. J., Gopinath, G., Reinhart, C. M., Posen, A., Prasad, E., & Mahbubani, K. (2020). How the economy will look after the coronavirus pandemic. Foreign Policy, 15.

Syrek, C., Kühnel, J., Vahle-Hinz, T., & de Bloom, J. (2022). Being an accountant, cook, entertainer and teacher—all at the same time: Changes in employees’ work and work-related well-being during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. International Journal of Psychology, 57(1), 20–32.

Syropoulos, S., & Markowitz, E. M. (2021). Prosocial responses to COVID-19: Examining the role of gratitude, fairness and legacy motives. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110488.

Su, R., & Shen, W. (2021). Is nationalism rising in times of the COVID-19 pandemic? Individual-level evidence from the United States. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 26(1), 169–187.

Tajfel, H. E. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

Tan, H. C., Ho, J. A., Teoh, G. C., & Ng, S. I. (2021). Is social desirability bias important for effective ethics research? A review of literature. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 10(2), 205–243.

Time (Accessed 10 June 2021). Heroes of the front lines: Stories of the courageous workers risking their own lives to save ours. https://time.com/collection/coronavirus-heroes/

Trujillo, A. J., Karmarkar, T., Alexander, C., Padula, W., Greene, J., & Anderson, G. (2020). Fairness in drug prices: Do economists think differently from the public? Health Economics, Policy and Law, 15(1), 18–29.

UNESCO (2020). Data from: COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed April 17 2020).

Van Barneveld, K., Quinlan, M., Kriesler, P., Junor, A., Baum, F., Chowdhury, A., & Rainnie, A. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 31(2), 133–157.

Van Bavel, J. J., Cichocka, A., Capraro, V., Sjåstad, H., & Conway, J. (2020). National identity predicts public health support during a global pandemic: Results from 67 nations. Nature Communications.

Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., Varley, D., Allgar, V. L., & De Beurs, E. (2020). Workplace stress, presenteeism, absenteeism, and resilience amongst university staff and students in the COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 588803.

Vogel, P. (2020). Nationalism: The even greater risk of the COVID-19 crisis. Institute for Management Development. . https://www.research-knowledge/articles/Nationalism-the-even-greater-risk-of-the-COVID-19-crisis/.

Voicu, M. C., & Babonea, A. (2011). Using the snowball method in marketing research on hidden populations. Challenges of the Knowledge Society, 1, 1341–1351.

Walker, P. G., Whittaker, C., Watson, O. J., Baguelin, M., Winskill, P., Hamlet, A., ... & Ghani, A. C. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 and strategies for mitigation and suppression in low-and middle-income countries. Science, 369(6502), 413-422

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409–421.

WHO (29 March 2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports

Wiedermann, W., & von Eye, A. (2015). Direction of effects in mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 20(2), 221.

World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2021). Available at: www.wbcsd.org/home.aspx. Accessed 10 June 2021.

Wright, K. A., Haastrup, T., & Guerrina, R. (2021). Equalities in freefall? Ontological insecurity and the long-term impact of COVID-19 in the academy. Gender, Work & Organization, 28, 163–167.

Zwolinski, M. (2008). The ethics of price gouging. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(3), 347–378.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This research was partially funded by the Research Authority at the Jerusalem College of Technology. All data is original data gathered for the purpose of this study and will be made available as requested. The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kay, A., Brender-Ilan, Y. Ethical decisions during COVID-19: level of moral disengagement and national pride as mediators. Asian J Bus Ethics 12, 25–48 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00161-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00161-2