Abstract

The key idea of the interventionist account of causation is that a variable A causes a variable B if and only if B would change if A were manipulated in an appropriate way. I argue that Woodward’s (Making things happen. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003) version of interventionism does not provide a sufficient condition for causation, insofar as it is not adequate for manipulations grounded on association laws. Such laws, which express relations of mutual dependence between variables, ground manipulative relationships which are not causal. I suggest that the interventionist analysis is sufficient for nomological dependence rather than for causation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The interventionist account has been generalized in order to be applicable to “actual causation”, where the relata are values of variables rather than variables. Cf. Woodward (2003, pp. 74–86). Woodward takes actual causation between values of variables to be equivalent to what has often been called “token causation”. Token causation relates particular events localized at a unique place and time, whereas type causation relates variables that can have many instantiations at many different times and places.

This clause does not apply to the case of direct causation.

The causal relation between specific variables bears close resemblance to but should not be confused with (what Woodward and others call) “actual causation”. Actual causation, as defined by Woodward (2003, p. 77) is a relation between specific values of variables, whereas specific variables are still variables.

I thank an anonymous referee for helping me clarify this point.

Pearl (2000, p. 12ff.).

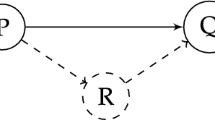

Maybe this distinction between genuine feedback cycles and mutually dependent variables lies behind Pearl’s stipulation that “directed graphs may include directed cycles (e.g., X → Y, Y → X), representing mutual causation or feedback processes, but not self-loops (e.g., X → X)” (Pearl 2000, p. 12). At the level of generic variables, this stipulation seems completely unmotivated. Indeed, as Pearl explicitly proves (2000, p. 237), in the absence of other influences, transitivity holds: if X → Y and Y → Z (but no additional influence X → Z along any pathway independent from the pathway running through Y), then X → Z. Transitivity seems to imply directly that every “directed cycle” X → Y, Y → X necessarily entails the existence a “self-loop” X → X. One coherent interpretation of Pearl’s remark would be to take “self-loops” to refer to what I have called relations of mutual dependence (which are circular both at the generic and at the specific levels), whereas directed cycles correspond to what I have called feedback cycles (which are circular only at the level of generic variables). However, Pearl’s framework cannot give any justification for his exclusion of self-loops, which therefore seems ad hoc.

I owe this reason and the example to an anonymous referee.

The example that follows is due to Spirtes and Scheines (2004).

I thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this way of arguing for the non-directedness of these edges.

According to Woodward, what is relative to sets of variables, are causal judgments, insofar as such judgments depend on “what we regard as serious possibilities” (Woodward 2008b, p. 205).

Thanks to an anonymous referee for suggesting me this way of putting the point.

See Hall (2004a).

I have argued for this claim elsewhere (Kistler 2006).

It does not establish it. Maybe the relations in the chain L–μ–L are not transitive for some other reason. But I can’t think of any such reason.

This conclusion has been suggested by an anonymous referee.

References

Carnap, R. (1928). Der logische Aufbau der Welt (p. 1998). Felix Meiner: Hamburg.

Cartwright, N. (1999). The dappled world: A study of the boundaries of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Collins, J., Hall, N., & Paul, L. A. (Eds.). (2004). Causation and counterfactuals. Cambridge (Massachusetts): MIT Press.

Cummins, R. (2000). How does it work? Versus what are the laws? Two conceptions of psychological explanation. In F. Keil & R. Wilson (Eds.), Explanation and cognition (pp. 117–145). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ehring, D. (1987). Causal relata. Synthese, 73, 319–328.

Fair, D. (1979). Causation and the flow of energy. Erkenntnis, 14, 219–250.

Hall, N. (2000/2004b), Causation and the price of transitivity, in Collins et al. (2004), pp. 181–204.

Hall, N. (2004a), Two concepts of causation, in Collins et al. (2004), pp. 225–276.

Hawley, K. (1999). Persistence and non-supervenient relations. Mind, 108, 53–67.

Hitchcock, C. (2001). The intransitivity of causation revealed in equations and graphs. Journal of Philosophy, 98, 273–299.

Kistler, M. (1998). Reducing causality to transmission. Erkenntnis, 48, 1–24.

Kistler, M. (2001a). Causation as transference and responsibility. In Wolfgang Spohn, Marion Ledwig, & Michael Esfeld (Eds.), Current issues in causation (pp. 115–133). Paderborn: Mentis.

Kistler, M. (2001b). Le concept de génidentité chez Carnap et Russell. In Sandra Laugier (Ed.), Carnap et la construction logique du monde (pp. 163–188). Paris: Vrin.

Kistler, M. (2006). Causation and laws of nature. London: Routledge.

McDermott, M. (1995). Redundant causation. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 46, 523–544.

Paul, L. A. (2004), Aspect causation, in Collins et al. (2004), pp. 205–224.

Pearl, J. (2000). Causality: Models, reasoning, and inference. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Schurz, G. (2002). Ceteris paribus laws: Classification and deconstruction. Erkenntnis, 57, 351–372.

Spirtes, P., Glymour, C., & Scheines, R. (2000). Causation, prediction and search (2nd ed.). Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press.

Spirtes, P., & Scheines, R. (2004). Causal inference of ambiguous manipulations. Philosophy of Science, 71, 833–845.

Spohn, W. (2001a), Bayesian nets are all there is to causal dependence, in M.C. Galavotti et al (eds.), Stochastic causality, Stanford: CSLI, and in W. Spohn, Causation, coherence, and concepts: A collection of essays, Springer 2009.

Spohn, W. (2001b). Deterministic causation. In Wolfgang Spohn, Marion Ledwig, & Michael Esfeld (Eds.), Current issues in causation (pp. 21–46). Paderborn: Mentis.

Spohn, W. (2006). Causation: An alternative. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 57, 93–119.

Strevens, M. (2007). Review of Woodward. Making Things Happen, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 74, 233–249.

Strevens, M. (2008). Comments on Woodward. Making Things Happen, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 77, 171–192.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodward, J. (2008a). Mental causation and neural mechanisms. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced (pp. 218–262). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodward, J. (2008b). Response to Strevens. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 77, 193–212.

Woodward, J. (2011), Interventionism and causal exclusion, http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/8651.

Acknowledgments

I thank Olivier Darrigol, Isabelle Drouet and Gernot Kleiter, as well as my auditors in Toulouse, Liblice, Salzburg and Konstanz, where I have presented earlier versions of this paper, for many helpful suggestions. The paper has been greatly improved thanks to the sharp and helpful critical remarks of two anonymous referees and of the editors of this special issue.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kistler, M. The Interventionist Account of Causation and Non-causal Association Laws. Erkenn 78 (Suppl 1), 65–84 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-013-9437-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-013-9437-4