Abstract

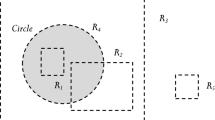

It is common to think that it’s possible for entities to spatially coincide in multiple ways: with overcrowding (as with two bosons located in the same region, not made of anything in common), and without overcrowding (as with a statue and a lump of clay). Typically, we can distinguish between these by claiming that uncrowded spatial overlap involves a sharing of parts, and crowded spatial overlap does not. However, if we think that mereologically unusual entities, such as extended simples or some kinds of gunk, can also spatially overlap in crowded and uncrowded ways, we lose the ability to distinguish between those varieties of spatial overlap via appeal to shared parts. Thus, we should either reject the possibilities that generated this difficulty, or we must look for an alternative explanation of these varieties of spatial overlap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A note on terminology: I’ll use ‘entity’ as a fully general term to apply to whatever exists. I’ll use ‘thing’ as a restriction on the category of entities, to (very roughly) pick out individuals that are referents of count nouns (though this isn’t perfect). ‘Object’ will be a further restriction, to apply to material things that are (at least typically taken to be) not events, regions, states of affairs, etc. I’ll use ‘plurality’ to pick out some entities where that may be one or more of them, and ‘stuff’ which (again: very roughly) picks out referents of mass terms. I’ll discuss the distinction between things and stuff in greater detail in Sect. 4. Obviously, I’m only giving a very rough characterization of these categories.

This is a technical sense of ‘part’; ‘proper part’ is a better candidate for corresponding to our ordinary concept of part.

I’ll use fuses and is a fusion of interchangeably. A fusion full-stop is something that is a fusion of one or more entities.

See Hudson (2006).

Though if you’re taking this relation as primitive, this will not be a definition. And it is controversial whether it is a listing of necessary and sufficient conditions.

Harmony principles are discussed in Schaffer (2009), Saucedo (2011), Uzquiano (2011), Gilmore (2014) and Leonard (2016). One very strong principle is Mereological Harmony, according to which the mereological and logical properties of and relations between objects exactly match the mereological and logical properties of and relations between the exact locations of those objects (Schaffer 2009).

For ease of discussion I’ll be assuming that all material objects have exact locations. The overlap problems I raise in Sect. 3 will not depend on this assumption (though rejecting it would complicate the presentation of the problems).

Being a spanner and being an extended simple can (at least logically) come apart. First, extended simples can multilocate rather than span (discussed in Parsons 2001; Hudson 2006; McDaniel 2007b). For instance, suppose an extended simple is exactly located at a composite region, r, and it is also exactly located at every subregion of that region (so it is multilocated within itself). It will not span that region even though it has no proper parts. I’ll set aside multilocating extended simples, but you can find arguments against them in Kleinschmidt (2011). Second, spanners can be composite rather than simple. For instance, suppose a composite object is such that it and every part of it is exactly located at the same extended, composite region, r, without having any parts (proper or improper) exactly located at any proper subregions of r. In this case, the composite object (and each of its parts!) will span r. And if that composite object is gunky, it and its parts can span r without there being any simples that do so.

This is nearly exactly the definition presented and discussed by Hudson (2006, p. 101).

An entity is maximally continuous just in case it fills a continuous region that is not a proper subregion of a continuous, filled region. A region is continuous, roughly, just in case, between any two subregions of the region, there’s a path between them that doesn’t go outside the region.

These cases can be as simple as: an exactly occupied, gunky region is divisible into halves, fourths, eighths, sixteenths, etc. The object occupying it is missing every other level of decomposition: it’s wholly decomposable into corresponding halves, but not fourths (it lacks the relevant fusions of smaller parts); into eighths but not sixteenths, etc.

Gibbard (1975). If you think the statue and/or lump have exact locations that are extended in time as well as in space, then assume the statue and lump coincide spatiotemporally rather than merely spatially.

Lewis (1991, p. 81).

There are differences between the statue/lump case and the cat fusion/cat plurality case. The cat-fusion and the plurality of all cats have a fusion in common (namely, the cat-fusion). The lump and the statue may not (depending on the other claims you make). Bricker (2016) takes sharing a fusion to be what it is for some plurality (that is, a collection with one or more members) to be the same portion of reality as another plurality. Though I’d like to remain neutral (at least here) on the question of whether the statue and lump share a fusion, I am appealing to an intuitive notion of portion of reality that may not have the features Bricker attributes to it.

This is also why I’ve avoided using terminology sometimes attached to these different kinds of colocation. For instance, coincidence or material coincidence has been presented as spatial overlap that involves part-sharing. And interpenetration has been presented as spatial overlap that involves no sharing of parts. (See, for instance, Olson 2001b; Paul 2006; Gilmore 2014.) I am avoiding attaching these terms to crowded and uncrowded colocation and overlap because if a theorist thinks there can be uncrowded spatial overlap (without colocation) of extended simples, then coincidence will come apart from uncrowded spatial overlap in at least some possible cases.

I’ll talk as if theorists accepting all of these steps would think lumps, statues, people, and ghosts could be extended simples, but really we just need that some entities colocating crowdedly and uncrowdedly are extended simples.

Ordinary statues aren’t spatially continuous, but we could imagine a possible statue that is spatially continuous.

One case like this is Eric Olson’s Problem of Disembodied Survival (Olson 2001a, §6), where a person is a body/soul fusion, but then shrinks down to just a mereologically simple soul while remaining numerically distinct from it. If we think the soul is located, this will be an example of uncrowded colocation involving at least one simple. And even if it is not located, as Guillon (2019) argues, there is a close connection between the person and the soul that will not be explainable via appeal to shared proper parts. Guillon argues that, if we think that post-shrinking the person and soul are distinct and stand in a constitution relation but not in any parthood relation, we will not be able to account for this relation via appeal to a sharing of parts or proper parts. One reason this kind of case is especially interesting is that, if we think this sort of case is possible, not only does it raise many of the same difficulties as those I raise in this paper, it also resists any account of constitution that appeals to locative features or shared material matter. So, for instance, a stuff-solution in response to this sort of example would have to appeal to something like immaterial stuff.

For instance, see the many responses to the Problem of Material Constitution covered in Rea, 1997.

If you think objects are extended in time as well as space, and exactly located at spacetime regions rather than merely at spatial regions, please read ‘spatial overlap’ as ‘spatiotemporal overlap’ throughout this paper.

I’m boldly making this claim, and am not saying much to back it up. You can interpret this part of the paper as a conditional: if you think this sort of case is possible, you face a puzzle. I think one reasonable response to this sort of case is to say that it is impossible; even if you think extended simples can colocate uncrowdedly, you might think they can’t spatially merely overlap uncrowdedly. For these theorists, the gunk and hybrid cases in the next subsection may be more compelling. And those who reject the possibility of even those cases may avoid my puzzle altogether by being sufficiently restrictive about possibility. This is the response I prefer, and I discuss it in the final section of this paper.

If you think it’s implausible that any possible table like this would lack a middle third part, perhaps you may prefer a different example. E.g., a theorist may think only sufficiently natural objects and parts of objects exist, and some of those natural parts overlap without sharing a natural part in common. (Such as an object with a red part and a bumpy part, but where the red + bumpy portion isn’t natural enough to be a part.) But if these examples aren’t compelling, I recommend the gunk and hybrid examples in the next section.

Note that there may or may not be a largest region that both spheres fill. We can imagine a case where the extended simple spheres overlap in space that is liberally decomposable (e.g., decomposable into infinitely many point-sized parts, and also into various fusions of those point-sized parts); in such a case, there would be a largest region filled by both spheres (though neither sphere would have a part occupying that region). However, a case like this would also require that the mereological structure of objects occupying locations, and the mereological structure of those locations, are significantly different; for some region, r, the object that occupies it is simple, though r is not simple. Some may worry about the conceivability of such a situation, and my cases don’t require any such differences between the structure of objects and the structure of locations. For instance, one may endorse the possibility of Case 3 by thinking it’s possible for the case to involve extended simple (and overlapping) regions as well as extended simple objects. (Though I’m not sure it is easier to conceive of this.).

I’ll discuss appeal to a partial constitution relation below.

This case was presented by Kit Fine in his Spring 2006 NYU Metaphysics lectures.

Simons, Parts: A Study in Ontology, pp. 153–154. In what follows I’ll sometimes talk about portions and subportions of stuff. I’ll follow Markosian (2004) in taking ‘portion of stuff’ to simply be synonymous with ‘some particular stuff’. Even though it is a count-noun, it is not intended to definitely refer to a thing. Instead, it is just intended to be a tool to help us more easily talk about particular stuff. So, for instance, when I say “two portions of stuff” that can be read as indicating that there’s some particular stuff, and some other particular stuff. And if I say one portion is a subportion of another, this can be taken to mean that some stuff is some of some other stuff.

Chappell (1973), p. 681. Here, constitution is taken to be a relation between stuff and things. If things can constitute stuff, and the relation is transitive, then things may also be able to constitute things. But even that sort of instantiation of the relation involves stuff.

We may think that sharing parts and sharing constituting stuff come apart in a variety of ways: for instance, we may think two objects can share parts and fail to share constituting stuff, or that some stuff can constitute each of two things, one of which is part of one further object, the other which is part of some other further object sharing no parts in common with the first object. For the purposes of this paper, I will not take a stand on whether these things are possible.

Markosian (2015, pp. 11–13).

For arguments against the adequacy of positing stuff in order to avoid colocation, see Kleinschmidt, (2007).

Another way of reading this is that everyone should like stuff: those who want to avoid colocation should posit stuff to help them do so. Those who are fine with colocation should posit stuff to help explain differences from weird possibilities that arise. This is not even close to a real dilemma, but it’s a more stuff-friendly reading of how my puzzle relates to colocation puzzles.

See Markosian (2004, 2015) for discussions of Pure Stuff Ontologies and Mixed Ontologies. Here, I’ll take stuff to be irreducible iff (i) it exists, and (ii) there are facts about stuff that are not reducible to facts not about stuff. I’ll take a kind of entity, k1, to be reducible to another kind of entity, k2, iff (i) entities of kind k1 exist and entities of kind k2 exist, and any facts about entities of kind k1 are reducible to facts about entities of kind k2.

Markosian (2015) responds to this worry by noting that stuff pulls its weight. For instance, in addition to his reasons for positing stuff that I’ve already mentioned, he argues that stuff seems to be part of our pre-theoretical picture of the world, and that translations of ordinary sentences about stuff into sentences about things don’t adequately capture the meanings of the original sentences, indicating that we have reason to posit irreducible stuff.

Markosian (2015) notes that one of the advantages of positing stuff is that it provides us with a kind of entity that is plausibly governed by the rules of Classical Extensional Mereology. This allows us to keep the elegance of CEM and the intuition that some entities exist that follow its rules, while also allowing us to avoid counterintuitive consequences of things following these rules, such as the existence of a fusion of you and the Eiffel Tower. Similar considerations can apply to additional rules governing decomposition.

A helpful reviewer pointed out that stuff theorists who take people to be portions of stuff will either have to claim that people can’t be made of different portions of stuff at different times (which is a challenge if you reject Four-Dimensionalism), or they’ll have to claim some portions of stuff do not have all of their subportions essentially.

Lewis (1991, p. 81).

There is a general strategy shared by the stuff solution and the reality response: to posit a new kind of entity, and claim that the difference between objects overlapping crowdedly and objects overlapping uncrowdedly comes down to a difference in how the objects relate to this new kind of entity. To play the role of a new sort of entity, we can appeal to portions of stuff, portions of reality, or something else altogether (such as properties).

See Kleinschmidt (2016).

References

Bricker, P. (2016). Composition as a Kind of identity. Inquiry, 59(3), 264–294.

Casati, R., & Varzi, A. (1999). Parts and places. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chappell, V. (1973). Matter. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 679–696.

Cotnoir, A. (2010). Anti-symmetry and non-extensional mereology. Philosophical Quarterly, 60, 396–405.

Gibbard, A. (1975). Contingent identity. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 4, 187–221.

Gilmore, C. (2014). Location and mereology. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2014/entries/location-mereology/.

Guillon, J.-B. (2019). Coincidence as parthood. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02105-z.

Hudson, H. (2006). The metaphysics of hyperspace. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kleinschmidt, S. (2007). Some things about stuff. Philosophical Studies, 135(3), 407–423.

Kleinschmidt, S. (2011). Multilocation and mereology. Philosophical Perspectives, 25, 253–276.

Kleinschmidt, S. (2016). Placement permissivism and logics of location. Journal of Philosophy, 113(3), 117–136.

Leonard, M. (2016). What is mereological haromony? Synthese, 193(6), 1949–1965.

Leonard, H., & Goodman, N. (1940). The calculus of individuals and its uses. Journal of Symbolic Logic, 5, 45–55.

Leśniewski, S. (1992). Collected works. S. J. Surma, J. T. Srzednicki, D. L. Barnett, & V. F. Rickey (Eds.). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Lewis, D. (1991). Parts of classes. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell, Inc.

Markosian, N. (1998). Simples. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 76, 213–226.

Markosian, N. (2004). Simples, stuff, and simple people. The Monist, 87, 405–428.

Markosian, N. (2015). The right stuff. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 93, 665–687.

McDaniel, K. (2003). Against MaxCon simples. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 81(2), 265–275.

McDaniel, K. (2007a). Brutal simples. In D. Zimmerman (Ed.), Oxford Studies in Metaphysics (vol. 3, pp. 233–265). Oxford University Press.

McDaniel, K. (2007b). Extended simples. Philosophical Studies, 133, 131–141.

McDaniel, K. (2009). Extended simples and qualitative heterogeneity. The Philosophical Quarterly, 59(235), 325–331.

Olson, E. (2001a). A compound of two substances. In K. Corcoran (Ed.), Soul, body, and survival (pp. 73–88). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Olson, E. (2001b). Material coincidence and the indiscernibility problem. The Philosophical Quarterly, 51(204), 337–355.

Parsons, J. (2001). Entension, or how it could happen that an object is wholly located in each of many places (unpublished). https://philpapers.org/archive/PAREO.pdf.

Parsons, J. (2004). Distributional properties. In F. Jackson & G. Priest (Eds.), Lewisian themes: The philosophy of David K. Lewis. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Paul, L. (2006). Coincidence as overlap. Nous, 40(4), 623–659.

Rea, M. (1997). Material constitution: A reader. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Saucedo, R. (2011). Parthood and location. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 6, 224–284.

Schaffer, J. (2009). Spacetime the one substance. Philosophical Studies, 145, 131–148.

Simons, P. (1987). Parts: A study in ontology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Spencer, J. (2010). A tale of two simples. Philosophical Studies, 148(2), 167–181.

Uzquiano, G. (2011). Mereological harmony. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 6, 199–223.

van Inwagen. (1990). Material Beings. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleinschmidt, S. The overlap problem. Philos Stud 178, 1801–1827 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01510-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01510-2