“…when presented with seemingly identical opportunities and motives, why does one person or organization turn to fraud and another does not? No one really knows.”

(Wells 2004, p. 74)

Abstract

We introduce the concept of fraud tolerance, validate the conceptualization using prior studies in economics and criminology as well as our own independent tests, and explore the relationship of fraud tolerance with numerous cultural attributes using data from the World Values Survey. Applying partial least squares path modeling, we find that people with stronger self-enhancing (self-transcending) values exhibit higher (lower) fraud tolerance. Further, respondents who believe in the importance of hard work exhibit lower fraud tolerance, and such beliefs mediate the relationship between locus of control and fraud tolerance. Finally, we find that people prone to traditional gender stereotypes demonstrate higher fraud tolerance and document subtle differences in the influence of these cultural attributes across age, religiosity, and gender groups. Our study contributes to research on corporate governance, ethics, and the antecedents of work-place dishonesty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The attitude studied in this paper has been considered in different contexts by scholars from different disciplines. Some examples include “tax morality” (focus on the single question and single context of tax compliance) and “civic cooperation” (focus on the aggregated country-level data that combined one indicator for several questions and explored its role in overall economic growth). Our use of “fraud tolerance” takes a different approach as discussed later in the paper.

The World Values Survey is a global research program that explores the evolution of people’s values around the world since 1981. Every five years researchers collect new data by administering a representative survey at a global scale that accesses people’s opinions on variety of issues. The World Values Survey web site provides open access to all this data (see World Values Survey 2020 for more details). We note numerous studies in accounting that use this data including Bhagwat and Liu (2020), Brochet et al. (2019), Isidro et al. (2020), Knechel et al. (2019), and Pevzner et al. (2015).

Such focus on individual and community-based differences in beliefs and values (i.e., intra-country rather than inter-country differences) is consistent with prior studies in criminology and allows us to avoid the confounding effects of cross-country differences in GDP, corruption, and similar macro-economic factors that might influence attitudes toward fraudulent behavior that are outside the scope of our investigation.

Fraud is inherently an interdisciplinary subject but scholars from different fields approach it from slightly different perspectives and utilize their own discipline-centric terminology. This leads to a multiplicity of labels to define similar constructs. For example, scholars from the disciplines outside accounting who are not familiar with fraud triangle framework often use the terms “attitude”, “verbalization”, “neutralization”, or “justification” to label perpetrator ability to rationalize the crime.

“Some of our most respectable citizens got their start in life by using other people’s money temporarily” or “In the real estate business there is nothing wrong about using deposits before the deal is closed” are examples of such general rationalizations (Cressey 1973, p. 96).

The examples of the specific dishonest or deviant economic acts vary across different waves of WVS but some questions such as justification of cheating on taxes are included more often than others.

Accounting scholars are more familiar with this labeling approach in the context of “generalized trust”, another proxy for social capital that relies on a single WVS question and which is extensively used in empirical accounting research.

See also summary in Torgler (2007a) and Torgler (2016). Some of these studies use the same questions from the European Value Survey. Results from these studies suggest that some individuals are “simply predisposed not to evade” taxes due to internalized social norms or potential guilt (Long and Swingen 1991, p. 130) and do not look for ways to cheat on their taxes (Alm et al. 1992; Dulleck et al. 2016).

As reported in Knack and Keefer (1997, p. 1257): “Twenty wallets containing $50 worth of cash and the addresses and phone numbers of their putative owners were ‘accidentally’ dropped in each of twenty cities, selected from fourteen different western European countries. Ten wallets were similarly ‘lost’ in each of twelve U. S. cities. … The percentage of wallets returned in each country … is correlated with TRUST at .67, and with item (d) of the CIVIC index, on the acceptability of ‘keeping money that you have found’ at .52.”.

These attributes are not randomly selected and represent some of the most studied constructs in the WVS survey, meaning that they have been extensively validated in prior research. For example, the dichotomy of self-enhancing vs. self-transcending values is a central point of the theory of Basic Human values, developed by Shalom H. Schwartz (e.g., Schwartz 1992, 1994, 1999, 2012). Locus of control is a fundamental construct capturing the differences in evaluation of environment “that has been formally studied for more than 50 years” (Galvin et al. 2018, p. 820; Johnson et al. 2015). Future research might explore other social attributes that may be relevant to fraud tolerance using other sources of data.

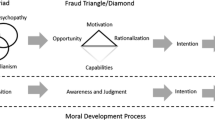

“Fraud diamond framework” is an extension of the “fraud triangle framework” and includes a perpetrator’s capability as a fourth fraud antecedent. According to this model, perpetrator’s capability reflects combination of personal traits and skills, including perpetrator’s position, intelligence, ego, ability to coerce, ability to lie, and resistance to stress (Wolfe and Hermanson 2004).

Sociologists often combine self-enhancing and self-transcending value orientations in a single measure to explain the societal roots of criminal behavior (Ganon and Donegan 2010; Itashiki 2011; Konty 2005), but psychologists stress the orthogonal nature of these dimensions (Frimer et al. 2011; Trapnell and Paulhus 2012; Wiggins 1991).

In sociology, self-enhancing vs. self-transcending values relate to the concept of “anomie”, the building block of “strain theory” (Donegan and Ganon 2008; Merton 1938; Messner and Rosenfeld 2001; Thorlindsson and Bernburg 2004). Konty (2005) suggested the label “micro-anomie”, measured as the difference between individual scores for self-enhancing and self-transcending values, to capture a particular cognitive state that prompts deviant behavior where self-interest dominates social-interest due to conflicting social messages. Research in psychology uses a different terminology while distinguishing two fundamental human motives: agency and communion. Similar to a self-enhancing orientation, agency “entails motives to advance the self within a social hierarchy: achievement, social power, or material wealth” (Frimer et al. 2011, p. 150). Communion, which is similar to a self-transcending orientation, reflects “benevolence to familiar others, or a more universalized concern for the well-being of disadvantaged, distant others, or the ecological well-being of the planet” (Frimer et al. 2011, p. 150). The labels of agency vs. communion are often referred to as “getting ahead” vs. “getting along” (Hogan and Holland 2003).

Early research explored work-related beliefs as part of the construct “Protestant Work Ethic” (PWE) as originally defined by Weber in 1905 (Weber 2001, reprint). In the 1970s several scholars developed measurement scales for PWE and the more general concept of “Work Ethic” (Mirels and Garrett 1971, Buchholz 1977, 1978). Consistent with this assumption about the link of hard work and morality, Aquino and Reed (2002) included the trait “hard-working” as one of nine characteristics of a moral person while developing their “moral identity” instrument.

Researchers used an internet sample designed by Knowledge Networks who completed all the field work of collecting the data. “KnowledgePanel®, created by Knowledge Networks, is a probability-based online Non-Volunteer Access Panel. Details are available at http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp accessed on 01/22/2019.

The sample size of 1,816 observations is sufficient for our analysis. Rough guideline suggests at least 10*maximum number of paths to be analyzed that lead to a single construct, or 10*8 = 80 in our case. Also, using the Cohen (1992) power table, the reasonable sample size for a model with six paths to one single construct is 157.

Jarvis et al. (2003) suggest that it is appropriate to model a construct as reflective when (1) assumed causality direction is from the construct to the indicators, (2) indicators are expected to be interchangeable and co-vary with each other, and (3) the indicators are assumed to have the same underlying antecedents and consequences. PLS also facilitates modeling of the latent constructs through formative (also known as composite) indicators. Formative indicators are not expected to be interchangeable, are not expected to correlate highly with each other, and capture different aspects of the underlying latent construct. While evaluating the appropriateness of a formative measurement model, researchers mostly focus on content validity (see Hair et al. 2017 for more details). Also, the choice of formative indicators should be grounded in theory and capture all major facets of the construct.

We exclude two questions that might be relevant to fraud: (1) “Stealing property” and (2) “Accepting a bribe”. Very few respondents openly justify such actions, resulting in high levels of kurtosis and skewness, e.g., kurtosis for “stealing the property” is 10.08, with skewness of 3.03. Our results remain substantially unchanged when we add “stealing property” and “accepting bribes” to the model (see more detailed discussion on p. 33–34), but we note high VIFs for both of these variables (> 3.3) that increase concern about common method bias. The indicators used in this study have less elevated degrees of kurtosis and skewness, e.g., kurtosis for “claiming benefits” is 4.153, with skewness of -2.17. Our approach is similar to those in other studies on “civic” or “economic” morality (e.g., Letki 2006).

While it would be desirable to use several indicators for construction of the latent variable, this is the only question in WVS that relates to locus of control.

One of the advantages of the PLS-SEM is that it does not assume a normal distribution for the data. However, this feature precludes the use of the parametric tests of significance, traditionally used in regression analyses. Instead, PLS-SEM relies on bootstrapping to estimate the significance of both outer loadings and path coefficients. “Bootstrapping is a resampling technique that draws a large number of subsamples from the original data (with replacement) and estimates models for each subsample. It is used to determine standard errors of coefficients to assess their statistical significance without relying on distributional assumptions” (Hair et al. 2017, p. 313). In theory, a larger number of bootstrapping samples leads to more reliable inferences, although improvements in the estimates of standard errors become negligible as each sample becomes a smaller portion of the entire analysis. Our results were consistent with those obtained with smaller bootstrapping samples such as 1000 and 500.

Prior research suggests that the attitudes related to civic cooperation and morality are stable over decades in large populations. Our state-level sample consists of 50 states plus the District of Columbia. We obtained the state statistics from www.statista.com except for employee complaints, which come from the website of the US Equal Opportunity Commission (https://www1.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/state_17.cfm accessed on 01/22/2019).

The heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations is a method of assessing the discriminant validity in PLS-SEM that outperforms the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Hair et al. 2017). The highest HTMT ratio in this sample was between the self-enhancing values and fraud tolerance constructs (0.358).

The highest level of collinearity between the latent constructs (Inner VIF values) was 1.09 between self-transcending values and fraud predisposition. The highest level of VIF for the indicators (Outer VIF values) was 2.56 in case of V53R: Beliefs that men make better business executives than women.

The bootstrap confidence interval does not include the “zero point” with a t value of 6.704.

The f-squared statistic of Locus of Control in explaining Beliefs in Hard work is 0.054.

In case of the “consistent PLS algorithm”, the relevant path coefficients increase in the same direction: path coefficient on self-enhancing values changes from 0.262 to 0.308 and the path coefficient on beliefs in hard work changes from -0.251 to -0.352.

We apply PLS-MGA approach with 5,000 bootstrap samples. We also conducted multi-group analyses comparing (1) people in managerial position vs. non-managerial position (as indicated by the WVS item V232 in USA version) and (2) people who characterize themselves as a “chief wage earner” vs. those who do not (as indicated by the WVS item V233 in USA version). Our tests do not reveal any significant differences in path coefficients between these groups.

Other potential denominations included Orthodox, Muslim, Jew, and Buddhist. We have fewer than 50 observations of these groups. 571 survey participants chose “None, do not belong to denominations” and 273 respondents selected “Other, non-specified”. These respondents are included in our first set of tests for religiosity overall. There were no significant differences in path coefficients between Protestants and those who selected “None, do not belong to denominations”, between Protestants and those who selected “Other, non-specified”, and between Catholics and those who selected “Other, non-specified”. The only difference between Catholics and those who selected “None, do not belong to denominations” was the stronger impact of Belief_in_Hard_Work on Fraud_Tolerance for Catholics.

We conduct a number of such post hoc tests that suggest it is unlikely that CMB presents a validity threat for the current study. First, Harman’s single-factor test reveals that only 20.3% of variance in the indicators used in our model is accounted by a single factor, which is much lower than the suggested 50% threshold. Following Kock (2015a) test for CMB in PLS-SEM, we do not observe any VIFs in excess of 3.3, again indicating that it is unlikely that our model suffers from common method bias. We also apply two techniques applicable to Confirmatory Factor Analysis under CB-SEM. In particular, we used the Unmeasured Common Latent Factor (UCLF) approach (Podsakoff et al. 2003, 2012) and the CFA marker (Williams et al. 2010). To create non-ideal marker variable that supposedly does not correlate with our constructs we used two questions from the World Value Survey: (1) whether participants perform “mostly manual” vs. “mostly intellectual” tasks (V231) and (2) whether participants perform “mostly routine” vs. “mostly creative” tasks (V232). The largest difference in standardized regression weights between the original model and the UCLF model is 0.11, which is below the recommended cut-off of 0.20. The difference between Chi-square of baseline and Method-C Model with the CFA marker is not significant at p < 0.05. Thus, the evidence provides additional support that our results are not affected by CMB.

As Speklé and Widener (2018, p. 11) put it in the context of the management accounting research: “Objective performance measures, thus, may lack content validity in that they do not necessarily capture what the researcher wishes to measure. Therefore, even though objective measures may be less biased, they could still be inferior to subjective, perceptual measures if the latter provide a better coverage of the performance dimensions of interest.”.

References

Akbaş, M., Ariely, D., & Yuksel, S. (2019). When is inequality fair? An experiment on the effect of procedural justice and agency. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 161, 114–127.

Akers, R. L. (1996). Is differential association/social learning cultural deviance theory? Criminology, 34(2), 229–247.

Albrecht, W. S. 2014. Iconic fraud triangle endures. Fraud Magazine, July/August.

Albrecht, W. S., & Albrecht, C. O. (2004). Fraud examination and prevention. Mason, OH: South-Western.

Alm, J., & Torgler, B. (2006). Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. Journal of economic psychology, 27(2), 224–246.

Alm, J., McClelland, G. H., & Schulze, W. D. (1992). Why do people pay taxes? Journal of Public Economics, 48(1), 21–38.

Alm, J., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & Torgler, B. (2006). Russian attitudes toward paying taxes—Before, during, and after the transition. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(12), 832–857.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Arce, D. G., & Gentile, M. C. (2015). Giving voice to values as a leverage point in business ethics education. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(3), 535–542.

Ariely, D., Garcia-Rada, X., Gödker, K., Hornuf, L., & Mann, H. (2019). The impact of two different economic systems on dishonesty. European Journal of Political Economy, 59, 179–195.

Arlow, P. (1991). Personal characteristics in college students’ evaluations of business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(1), 63–69.

Arnaud, A., & Schminke, M. (2012). The ethical climate and context of organizations: A comprehensive model. Organization Science, 23(6), 1767–1780.

Arnold, T. (2001). Rethinking moral economy. American Political Science Review, 95(1), 85–95.

Association of Fraud Examiners (ACFE) (2020a). Report to the nations: 2020 global study on occupational fraud and abuse. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://acfepublic.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/2020-Report-to-the-Nations.pdf.

Association of Fraud Examiners (ACFE) (2020b). What is fraud. Retrieved May 11, 2020, from https://www.acfe.com/fraud-101.aspx.

Bampton, R., & Cowton, C. J. (2013). Taking stock of accounting ethics scholarship: A review of the journal literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(3), 549–563.

Barling, J., Dupre, K., & Hepburn, G. (1998). Effects of parents’ job insecurity on children’s work beliefs and attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 112–118.

Baron, R. A., Zhao, H., & Miao, Q. (2015). Personal motives, moral disengagement, and unethical decisions by entrepreneurs: Cognitive mechanisms on the “slippery slope.” Journal of Business Ethics, 128(1), 107–118.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2016). Mindful economics: The production, consumption, and value of beliefs. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 141–164.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2001). Economics and social behaviour: Do people mean what they say? Implications for subjective survey data. American Economic Review, 91(2), 67–72.

Bhagwat, V., & Liu, X. (2020). The role of trust in information processing: Evidence from security analysts. The Accounting Review, 95(3), 59–83.

Bigelow, L., Lundmark, L., Parks, J. M., & Wuebker, R. (2014). Skirting the issues: Experimental evidence of gender bias in IPO prospectus evaluations. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1732–1759.

Birnberg, J., & Snodgrass, C. (1988). Culture and control: A field study. Accounting, Organizations, and Society, 13(5), 447–464.

Bouwens, J. (2017). Survey research: Facts and perceptions. In T. Libby & L. Thorne (Eds.), Routledge companion to behavioral accounting research (pp. 213–224). London: Routledge.

Braithwaite, J. (1985). White collar crime. Annual Review of Sociology, 11, 1–25.

Brochet, F., Miller, G. S., Naranjo, P., & Yu, G. (2019). Managers’ cultural background and disclosure attributes. The Accounting Review, 94(3), 57–86.

Bruns, W., & Merchant, K. (1990). The dangerous morality of managing earnings. Management Accounting, 72(2), 22–25.

Buchholz, R. A. (1977). The belief structure of managers relative to work concepts measured by a factor analytic model. Personnel Psychology, 30(4), 567–587.

Buchholz, R. A. (1978). An empirical study of contemporary beliefs about work in American society. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(2), 219–227.

Campana, P. (2016). When rationality fails: Making sense of the “slippery slope” to corporate fraud. Theoretical Criminology, 20(3), 322–339.

Cherry, J. (2006). The impact of normative influence and locus of control on ethical judgments and intentions: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(2), 113–132.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–358). NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Chiu, R. K. (2003). Ethical judgment and whistleblowing intention: Examining the moderating role of locus of control. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1/2), 65–74.

Chonko, L. B., & Hunt, S. D. (1985). Ethics and marketing management: An empirical examination. Journal of Business Research, 13(4), 339–360.

Christensen, A., Cote, J., & Latham, C. K. (2018). Developing ethical confidence: The impact of action-oriented ethics instruction in an accounting curriculum. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(4), 1157–1175.

Coffman, K. B., Exley, C.L., & Niederle, M. (2017). When gender discrimination is not about gender. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=53686.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Cohen, J., Ding, Y., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2010). Corporate fraud and managers’ behavior: Evidence from the press. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2), 271–315.

Coleman, J. W. (1987). Toward an integrated theory of white-collar crime. American Journal of Sociology, 93(2), 406–439.

Collins, J. D., Ulluenbruck, K., & Rodriguez, P. (2009). Why firms engage in corruption: A top management perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 89–108.

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). (2013). Internal control– Integrated framework. Retrieved April 3, 2018, from https://www.coso.org/Pages/ic.aspx.

Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business Psychology, 25(3), 325–334.

Corcoran, K., Pettinicchio, D., & Robbins, B. (2012). Religion and the acceptability of white-collar crime: A cross-national analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51(3), 542–567.

Cote, J., Goodstein, J., & Latham, C. K. (2011). Giving voice to values: A framework to bridge teaching and research efforts. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 8(1), 370–375.

Cressey, D. R. (1953). Other people’s money: A study in the social psychology of embezzlement. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

Cressey, D. R. (1973 reprint). Other people’s money: A study in the social psychology of embezzlement. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith.

Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Hoegl, M. (2004). Cross-national differences in managers’ willingness to justify ethically suspect behaviors: A test of institutional anomie theory. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 411–421.

Cummings, R. G., Martinez-Vazquez, J., McKee, M., & Torgler, B. (2009). Tax morale affects tax compliance: Evidence from surveys and an artefactual field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 70(3), 447–457.

Darwish, A. Y. (2000). The Islamic work ethic as a mediator of the relationship between locus of control, role conflict and role ambiguity—A study in an Islamic country setting. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(4), 283–298.

Dellaportas, S. (2006). Making a difference with a discrete course on accounting ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 65(4), 391–404.

Dent, J. (1991). Accounting and organizational cultures: A field study of the emergence of a new organizational reality. Accounting, Organizations, and Society, 16(8), 705–732.

Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316.

Donegan, J. J., & Ganon, M. W. (2008). Strain, differential association, and coercion: Insights from the criminology literature on causes of accountant’s misconduct. Accounting and the Public Interest, 8(1), 1–20.

Donnelly, D. P., Quirin, J. J., & O’Bryan, D. (2003). Auditor acceptance of dysfunctional audit behavior: An explanatory model using auditors’ personal characteristics. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 15(1), 87–110.

Doran, C., & Littrell, R. (2013). Measuring mainstream US cultural values. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 261–280.

Dorminey, J. W., Fleming, A. S., Kranacher, M.-J., & Riley, R. A. (2010). Beyond the fraud triangle: Enhancing deterrence of economic crimes. The CPA Journal, 80(7), 17–23.

Dorminey, J., Fleming, A. S., Kranacher, M.-J., & Riley, R. A. (2012). The evolution of fraud theory. Issues in Accounting Education, 27(2), 555–579.

Dulleck, U., Fooken, J., Newton, C., Ristl, A., Schaffner, M., & Torgler, B. (2016). Tax compliance and psychic costs: Behavioral experimental evidence using a physiological marker. Journal of Public Economics, 134, 9–18.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House.

Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindset: How you can fulfill your potential. New York, NY: Constable and Robinson Limited.

Eabrasu, M. (2020). Cheating in business: A metaethical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(3), 519–532.

Edwards, M. G., & Kirkham, N. (2014). Situating “giving voice to values”: A meta-theoretical evaluation of a new approach to business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(3), 477–495.

Epstein, B. J., & Ramamoorti, S. (2016). Today’s fraud risk models lack personality. The CPA Journal, 86(3), 15–21.

Fay, M., & Williams, L. (1993). Gender bias and the availability of business loans. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(4), 363–376.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (2006). The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism—Experimental evidence and new theories. In S.-C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving, reciprocity and altruism (pp. 615–691). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Fornell, C., & Cha, J. (1994). Partial least squares. In R. P. Bagozzi (Ed.), Advanced methods in marketing research (pp. 52–78). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Forte, A. (2004). Antecedents of managers’ moral reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 51(4), 315–347.

Forte, A. (2005). Locus of control and the moral reasoning of managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 58(1/3), 65–77.

Free, C., & Murphy, P. R. (2015). The ties that bind: The decision to co-offend in fraud. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(1), 18–54.

Frey, B., & Torgler, B. (2007). Tax morale and conditional cooperation. Journal of Comparative Economics, 35(1), 136–159.

Frimer, A. J., Walker, L. J., Dunlop, W. L., Lee, B. H., & Riches, A. (2011). The integration of agency and communion in moral personality: Evidence of enlightened self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 149–163.

Fritzsche, D. J. (1988). An examination of marketing ethics: Role of the decision maker, consequences of the decision, management position and sex of the respondent. Journal of Macromarketing, 8(2), 29–39.

Fritzsche, D. J., & Oz, E. (2007). Personal values’ influence on the ethical dimension of decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(4), 335–343.

Frost, T., & Wilmesmeier, J. (1983). Relationship between locus of control and moral judgments among college students. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 57(3), 931–939.

Furnham, A. (1990). A content, correlational, and factor analytic study of seven questionnaire measures of the Protestant work ethic. Human Relations, 43(4), 383–399.

Galvin, B. M., Randel, A. E., Collins, B. J., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 820–833.

Ganon, M. W., & Donegan, J. J. (2010). Microanomie as an explanation of tax fraud: A preliminary investigation. In T. Stock (Ed.), Advances in Taxation 19 (pp. 123–143). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Gilligan, C. (1993). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gladwell, M. (2002). The talent myth. The New Yorker 22 July. Retrieved April 3, 2018, from http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/07/22/the-talent-myth

Gneezy, U. (2005). Deception: The role of consequences. American Economic Review, 95(1), 384–394.

Gopal, R. J., Marsden, R., & Vanthienen, J. (2011). Information mining—Reflections on recent advancements and the road ahead in data, text, and media mining. Decision Support Systems, 51(4), 727–731.

Groysberg, B. (2010). Chasing stars: The myth of talent and the portability of performance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Haithem, Z., & Jeongsoo, P. (2019). The effects of cultural tightness and perceived unfairness on Japanese consumers’ attitude towards insurance fraud: The mediating effect of rationalization. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 24(1–2), 21–30.

Halpern, D. (2001). Moral values, social trust, and inequality: Can values explain crime? The British Journal of Criminology, 41(2), 236–251.

Hay, D. C., Knechel, W. R., & Wong, N. (2006). Audit fees: A meta-analysis of the effect of supply and demand attributes. Contemporary Accounting Research, 23(1), 141–191.

Heinemann, F. (2011). Economic crisis and morale. European Journal of Law and Economics, 32(1), 35–49.

Heinicke, A., Guenther, T. W., & Winder, S. K. (2016). An examination of the relationship between the extent of a flexible culture and the levers of control system: The key role of beliefs control. Management Accounting Research, 33, 25–41.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-vased structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Hogan, J., & Holland, B. (2003). Using theory to evaluate personality and job performance relations: A socioanalytic perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 100–112.

Hogan, C. E., Zabihollah, R., Riley, R. A., & Velury, U. K. (2008). Financial statement fraud: Insights from the academic literature. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 27(2), 231–251.

Inglehart, R., Haerpfer, C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., Puranen, B. et al. (eds.). (2014). World Values Survey: Round Six—Country-Pooled Datafile Version: www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. JD Systems Institute, Madrid.

International Standard on Auditing (ISA) 240. The auditor’s responsibilities relating to fraud in an audit of financial statements. Retrieved April 3, 2018, from http://www.ifac.org/system/files/downloads/a012-2010-iaasb-handbook-isa-240.pdf.

Isidro, H., Nanda, D., & Wysocki, P. D. (2020). On the relation between financial reporting quality and country attributes: Research challenges and opportunities. The Accounting Review, 95(3), 279–314.

Itashiki, M. R. (2011). Explaining “everyday crime”: A test of anomie and relative deprivation theory. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas. Retrieved April 3, 2018, from http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc103334/.

James, H. S. (2015). Generalized morality, institutions and economic growth, and the intermediating role of generalized trust. KYKLOS, 68(2), 165–196.

Jarvis, C. B., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2003). A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 199–218.

Jha, A., & Chen, Y. (2015). Audit fees and social capital. The Accounting Review, 90(2), 611–639.

Johnson, E. N., Kuhn, J. R., Jr., Apostolou, B. A., & Hassell, J. M. (2013). Auditor perceptions of client narcissism as a fraud attitude risk factor. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 32(1), 203–219.

Johnson, R. E., Rosen, C. C., Chang, C.-H., & Lin, S.-H. (2015). Getting to the core of locus of control: Is it a core evaluation of the self or the environment? Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(5), 1568–1578.

Jolls, C., Sunstein, C. R., & Thaler, R. (1998). A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stanford law review, 50(5), 1471–1550.

Jones, H. B. (1997). The Protestant ethic: Weber’s model and the empirical literature. Human Relations, 50(7), 757–778.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. The American Economic Review, 76(4), 728–741.

Karstedt, S., & Farrall, S. (2006). The moral economy of everyday crime. British Journal of Criminology, 46(6), 1011–1037.

Kidron, A. (1978). Work values and organizational commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 21(2), 239–247.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economy payoff? A cross-county investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288.

Knechel, W. R., Mintchik, N., Pevzner, M., & Velury, U. (2019). The effects of generalized trust and civic cooperation on the Big N presence and audit fees across the globe. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 38(1), 193–219.

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10.

Kock, N. (2015). One-tailed or two-tailed P values in PLS-SEM? International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(2), 1–7.

Konrad, K. A., & Qari, S. (2012). The last refuge of a scoundrel? Patriotism and tax compliance. Economica, 79(315), 516–533.

Konty, M. (2005). Microanomie: The cognitive foundations of the relationship between anomie and deviance. Criminology, 43(1), 107–132.

Lance, C. E., Dawson, B., Birkelbach, D., & Hoffman, B. J. (2010). Method effects, measurement error, and substantive conclusions. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 435–455.

Lan, G., Gowing, M., McMahon, S., Rieger, F., & King, N. (2008). A study of the relationship between personal values and moral reasoning of undergraduate business students. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(1/2), 121–139.

Letki, N. (2006). Investigating the roots of civic morality: Trust, social capital, and institutional performance. Political Behavior, 28(4), 305–325.

Lin, C., & Ding, C. G. (2003). Modeling information ethics: The joint moderating role of locus of control and job insecurity. Journal of Business Ethics, 48(4), 335–346.

Long, S., & Swingen, J. (1991). The conduct of tax-evasion experiments: Validation, analytical methods, and experimental realism. In P. Webley, H. Robben, H. Elffers, & D. Hessing (Eds.), Tax evasion: An experimental approach (pp. 128–138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lopes, C. A. (2010). Consumer morality in times of economic hardship: Evidence from the European Social Survey. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 34(2), 112–120.

Luthar, H. K., DiBattista, R. A., & Gautschi, T. (1997). Perception of what the ethical climate is and what it should be: The role of gender, academic status, and ethical education. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(2), 205–217.

Ma, H.-K. (1985). Cross-cultural study of the development of law-abiding orientation. Psychological Reports, 57(3), 967–975.

MacDonald, A. P. (1971). Correlates of the ethics of personal conscience and the ethics of social responsibility. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 37(3), 443.

MacLellan, C., & Dobson, J. (1997). Women, ethics, and MBAs. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(11), 1201–1209.

Malmi, T., & Brown, D. A. (2008). Management control systems as a package—Opportunities, challenges and research directions. Management Accounting Research, 19(4), 287–300.

Martinov-Bennie, N., & Mladenovic, R. (2015). Investigation of the impact of an ethical framework and an integrated ethics education on accounting students’ ethical sensitivity and judgment. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(1), 189–203.

Mayhew, B. W., & Murphy, P. R. (2009). The impact of ethics education on reporting behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 86(3), 397–416.

Mayhew, B. W., & Murphy, P. R. (2014). The impact of authority on reporting behavior, rationalization, and affect. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(2), 420–433.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

McCarty, J. A., & Shrum, L. J. (2001). The Influence of individualism, collectivism, and locus of control on environmental beliefs and behavior. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 20(1), 93–104.

Merchant, K. A., & Otley, D. T. (2007). A review of the literature on control and accountability. In C. S. Chapman, A. G. Hopwood, & M. D. Shields (Eds.), Handbook of management accounting research (Vol. 2, pp. 785–802). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Merchant, K. A., & Rockness, J. (1994). The ethics of managing earnings: An empirical investigation. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 13(1), 79–94.

Merchant, K. A., & White, L. (2017). Linking the ethics and management control literatures. Advances in Management Accounting, 28, 1–29.

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672–682.

Messner, S. F., & Rosenfeld, R. (2001). Crime and the American dream. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Mickiewicz, T., Rebmann, A., & Sauka, A. (2019). To pay or not to pay? Business owners’ tax morale: Testing a neo-institutional framework in a transition environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(1), 75–93.

Milberg, S. J., Smith, H. J., & Burke, S. J. (2000). Information privacy: Corporate management and national regulation. Organization Science, 11(1), 35–57.

Mintchik, N. M., & Farmer, T. A. (2009). Associations between epistemological beliefs and moral reasoning: Evidence from accounting. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(2), 259–275.

Mintchik, N., & Riley, J. (2019). Rationalizing fraud: How thinking like a crook can help prevent fraud. CPA Journal, 89(3), 44–50.

Mirels, H. L., & Garrett, J. B. (1971). The Protestant ethic as a personality variable. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 36(1), 40–44.

Morales, J., Gendron, Y., & Guenin-Paracini, H. (2014). The construction of the risky individual and vigilant organization: A genealogy of the fraud triangle. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 39(3), 170–194.

Murk, D., & Addleman, J. (1992). Relations among moral reasoning, locus of control, and demographic variables among college students. Psychological Reports, 70(2), 467–476.

Murphy, P. R. (2012). Attitude, Machiavellianism and the rationalization of misreporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37(4), 242–259.

Murphy, P. R., & Dacin, M. T. (2011). Psychological pathways to fraud: Understanding and preventing fraud in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(4), 601–618.

Murphy, P. R., & Free, C. (2016). Broadening the fraud triangle: Instrumental climate and fraud. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 28(1), 41–56.

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2010). Different roles, different strokes: Organizing virtual customer environments to promote two types of customer contributions. Organization Science, 21(2), 554–572.

Ng, T. W. H., Sorensen, K. L., & Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1057–1087.

Nitzl, C. (2016). The use of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. Journal of Accounting Literature, 37, 19–35.

Noreen, E. (1988). The economics of ethics: A new perspective on agency theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 13(4), 359–436.

Nowicki, S., & Strickland, B. R. (1973). A locus of control scale for children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 40(1), 148–154.

O’Reilly, C. (1989). Corporations, culture and commitment: Motivation and social control in organizations. California Management Review, 31(4), 9–25.

O’Reilly, C., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492–499.

PCAOB. 2020. Auditing Standard 2401: Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from: https://pcaobus.org/Standards/Auditing/Pages/AS2401.aspx.

Pevzner, M., Xie, F., & Xin, X. (2015). When firms talk, do investors listen? The role of trust in stock market reactions to corporate earnings announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 190–223.

Plufrey, C., & Butera, F. (2013). Why neoliberal values of self-enhancement lead to cheating in higher education. A motivational account. Psychological Science, 24(11), 2153–2162.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual review of psychology, 63, 539–569.

Pratt, M., Golding, G., & Hunter, W. (1983). Aging as ripening: Character and consistency of moral judgment in young, mature, and older adults. Human Development, 26(5), 277–288.

Ramamoorti, S., & Olsen, W. (2007). Fraud: The human factor. Financial Executive, 53–55.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., & Isakson, H. R. (2010). Ethics of tomorrow’s business managers the influence of personal beliefs and values, individual characteristics, and situational factors. Journal of Education for Business, 75(6), 321–330.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., & Singhapakdi, A. (1998). Do consumers’ ethical beliefs vary with age? A substantiation of Kohlberg’s typology in marketing. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 6(2), 26–38.

Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 762–800.

Ridgeway, C. L. (1997). Interaction and the conservation of gender inequality: Considering employment. American Sociological Review, 62(2), 218–235.

Ridgeway, C. L. (2011). Framed by gender: How gender inequality persists in the modern World. UK: Oxford University Press.

Rodriguez-Justicia, D., & Theilen, B. (2018). Education and tax morale. Journal of Economic Psychology, 64, 18–48.

Rokeach, M. (1968). Beliefs, attitudes, and values: A theory of organization and change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rose, D. C. (2011). The moral foundations of economic behavior. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28.

Ruegger, D., & King, E. W. (1992). A study of the effect of age and gender upon student business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(3), 179–186.

Schrand, C., & Zechman, S. (2012). Executive overconfidence and the slippery slope to financial misreporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53(1/2), 311–329.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S. C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method and applications (pp. 85–119). New York, NY: Sage.

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48(1), 23–47.

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2(1). Retrieved April 3, 2018, from https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116.

Scott, K. A., & Brown, D. J. (2006). Female first, leader second? Gender bias in the encoding of leadership behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 230–242.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476.

Sihag, V., & Rijsijk, S. A. (2019). Organizational controls and performance outcomes: A meta-analytic assessment and extension. Journal of Management Studies, 56(1), 91–133.

Sikula, A., Sr., & Costa, A. D. (1994). Are women more ethical than men? Journal of Business Ethics, 13(11), 859–867.

Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control: How managers use innovative control systems to drive strategic renewal. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Singhapakdi, A., & Vitell, S. J. (1991). Analyzing the ethical decision making of sales professionals. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 11(4), 1–12.

Singhapakdi, A., Rao, C. P., & Vitell, S. J. (1996). Ethical decision making: An investigation of services marketing professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(6), 635–645.

Smith, P. L., & Oakley, E. F., III. (1997). Gender-related differences in ethical and social values of business students: Implications for management. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(1), 37–45.

Soltes, E. (2016). Why they do it: Inside the mind of the white-collar criminal. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

Speklé, R. F., & Widener, S. K. (2018). Challenging issues in survey research: Discussion and suggestions. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 30(2), 3–21.

Stack, S., & Kposowa, A. (2006). The effect of religiosity on tax fraud acceptability: A cross-national analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(3), 325–351.

Staples, D. S., Hulland, J. S., & Higgins, C. (1999). A self-efficacy theory explanation for the management of remote workers in virtual organizations. Organization Science, 10(6), 758–776.

Steenhaut, S., & van Kenhove, P. (2006). An empirical investigation of the relationships among a consumer’s personal values, ethical ideology and ethical beliefs. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(2), 137–155.

Suh, I., Sweeney, J., Linke, K., & Wall, J. (2020). Boiling the frog slowly: The immersion of C-suite financial executives into fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(3), 645–673.

Sutherland, E. H. (1940). The white-collar criminal. American Sociological Review, 5(1), 1–12.

Tennyson, S. (2008). Moral, social, and economic dimensions of insurance claims fraud. Social Research, 75(4), 1181–1204.

Theoharakis, V., Voliotis S. & Pollack, J. M. (2020). Going down the slippery slope of legitimacy lies in early‑stage ventures: The role of moral disengagement, Journal of Business Ethics, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04508-2.

Thorlindsson, T., & Bernburg, J. G. (2004). Durkheim’s theory of social order and deviance: A multi-level test. European Sociological Review, 20(4), 271–285.

Torgler, B. (2007). Tax compliance and tax morale: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Torgler, B. (2007b). Tax morale in central and eastern European countries. In N. Hayoz & S. Hug (Eds.), Tax evasion, trust and state capacities. How good is tax morale in central and eastern Europe? (pp 155–186). Bern: Peter Lang.

Torgler, B. (2012). Tax morale, eastern Europe and European enlargement. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 45(1/2), 11–25.

Torgler, B. (2016). Tax compliance and data: What is available and what is needed. The Australian Economic Review, 49(3), 352–364.

Torgler, B., & Schneider, F. G. (2007). What shapes attitudes toward paying taxes? Evidence from multicultural European countries. Social Science Quarterly, 88(2), 443–470.

Torgler, B., & Schneider, F. (2009). The impact of tax morale and institutional quality on the shadow economy. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 228–245.

Torgler, B., & Valev, N. T. (2010). Gender and public attitudes towards corruption and tax evasion. Contemporary Economic Policy, 28(4), 554–568.

Torgler, B., Schaffner, M., & Macintyre, A. (2010). Tax compliance, tax morale, and governance quality. In J. Alm, J. Martinez-Vazquez, & B. Torgler (Eds.), Developing alternative frameworks for explaining tax compliance (pp. 56–73). London: Routledge.

Trapnell, P. D., & Paulhus, D. L. (2012). Agentic and communal values: Their scope and measurement. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94(1), 39–52.

Trevino, L. (1990). Bad apples in bad barrels: A causal analysis of ethical decision-making behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(4), 378–385.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Trompeter, G. M., Carpenter, T. D., Desai, N., Jones, K. L., & Riley, R. (2013) A synthesis of fraud-related research. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 32(1, Supplement), 287–321.

Tsalikis, J., & Ortiz-Buonafina, M. (1990). Ethical beliefs’ differences of males and females. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(6), 509–517.

Tseng, L. M., & Kuo, C.-L. (2014). Customers’ attitudes toward insurance frauds: An application of Adams’ equity theory. International Journal of Social Economics, 41(11), 1038–1054.

Tsui, J. S. L., & Gul, F. A. (1996). Auditors’ behaviour in an audit conflict situation: A research note on the role of locus of control and ethical reasoning. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 21(1), 41–51.

Umphress, E. E., & Bingham, J. B. (2011). When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organization Science, 22(3), 621–640.

Vitell, S. J., Lumpkin, J. R., & Rawwas, M. Y. A. (1991). Consumer ethics: An investigation of the ethical beliefs of elderly consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(5), 365–375.

Weber, M. (2001). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. London: Routledge.

Wells, J. T. (1997). Occupational fraud and abuse: How to prevent and detect asset misappropriation, corruption, and fraudulent statements. Austin, TX: Obsidian Publishing Company.

Wells, J. T. (2004). New approaches for fraud deterrence. Journal of Accountancy, 197(2), 72–76.

Welsh, K. 2017. Bankruptcy fraud — rarely caught and rarely prosecuted. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.creditinfocenter.com/bankruptcy/bankruptcy-fraud-rarely-caught.shtml.

Wiggins, J. S. (1991). Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal behavior. In D. Cicchetti & W. M. Grove (Eds.), Thinking clearly about psychology: Essays in honor of Paul E. Meehl: Vol. 2. Personality and psychopathology (pp. 89–113). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 477–514.

Wold, H. (1985). Partial least squares. In S. Kotz & N. L. Johnson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences (Vol. 6, pp. 581–591). New York: Wiley.

Wolfe, D. T., & Hermanson, D. R. (2004). The fraud diamond: Considering the four elements of fraud. The CPA Journal, 74(12), 38–42.

World Values Survey (2020). World Values Survey—Who we are. Retrieved May 16, 2020, from: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp.

Yousef, D. A. (2000). The Islamic work ethic as a mediator of the relationship between locus of control, role conflict, and role ambiguity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(4), 283–302.

Zahra, S. A., Priem, R. L., & Rasheed, A. A. (2005). The antecedents and consequences of top management fraud. Journal of Management, 31(6), 803–828.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Accounting and Business Ethics section editor of “Journal of Business Ethics” Charles Cho, three anonymous reviewers, participants of 2017 American Accounting Association Ethics Symposium, 2018 American Accounting Association Forensic Accounting Section Meeting, 2018 AAA annual meeting, 2019 Conference of the AAA Public Interest Section, the workshop in University of Cincinnati and anonymous reviewers for 2018 Audit Midyear Meeting for providing feedback on this project. We are also grateful to Anna Alon, Jan Bouwens, Renee Flasher, Theresa Libby, Pamela Murphy, and Sri Ramamoorti for their helpful comments. Special thanks to Hyun Park for assistance with running the audit fee model.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Appendices

Appendix 1: World Values Survey Questions Used in This Study

Introduction by Interviewer

We are carrying out a global study of what people value in life. This study will interview samples representing most of the world's people. You have been selected at random as part of a representative sample of the people in the United States. We'd like to ask your views on a number of different subjects. Your input will be treated strictly confidential but it will contribute to a better understanding of what people all over the world believe and want out of life.

Questions for Independent Variables

Indicators for Dependent Variable: Fraud Tolerance

Please tell me for each of the following actions whether you think it can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between, using this card. (Read out and code one answer for each statement):

Never justifiable | Always justifiable | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

V198. Claiming government benefits to which you are not entitled | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

V199. Avoiding a fare on public transport | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

V201. Cheating on taxes if you have a chance | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Questions for Independent Variables

Indicators for Gender Bias

For each of the following statements I read out, can you tell me how strongly you agree or disagree with each. Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree?

Strongly agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

V 51. On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

V 52. A university education is more important for a boy than for a girl | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

V 53. On the whole, men make better business executives than women do | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Indicators for Self-enhancing Values

Now I will briefly describe some people. Using this card, would you please indicate for each description whether that person is very much like you, like you, somewhat like you, not like you, or not at all like you?

Very much like me | Like me | Somewhat like me | A little like me | Not like me | Not at all like me | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

V71. It is important to this person to be rich; to have a lot of money and expensive things | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

V 73. It is important to this person to have a good time; to "spoil" oneself | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

V 75. Being very successful is important to this person; to have people recognize one’s achievements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

V 76. Adventure and taking risks are important to this person; to have an exciting life | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Indicators for Self-transcending/Communal Values

Now I will briefly describe some people. Using this card, would you please indicate for each description whether that person is very much like you, like you, somewhat like you, not like you, or not at all like you?

Very much like me | Like me | Somewhat like me | A little like me | Not like me | Not at all like me | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

V74. It is important to this person to do something for the good of society | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

V 78. Looking after the environment is important to this person; to care for nature and save life resources | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Indicator for Locus of Control

V55. Some people feel they have completely free choice and control over their lives, while other people feel that what they do has no real effect on what happens to them. Please use this scale where 1 means “no choice at all” and 10 means “a great deal of choice” to indicate how much freedom of choice and control you feel you have over the way your life turns out (code one number):

No choice at all | A great deal of choice | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Indicators for Belief in Hard Work

Please indicate your views on each of the following issues. Using a 1 to 10 scale, where 1 means you agree completely with the statement on the left and 10 means you agree completely with the statement on the right, please select the number that best reflects your own views on each issue. (Code one number for each issue):

V99

Competition is good. It stimulates people to work hard and develop new ideas | Competition is harmful. It brings out the worst in people | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

V100

In the long run, hard work usually brings a better life | Hard work doesn’t generally bring success—it’s more a matter of luck and connections | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Appendix 2: Summary list of all indicator variables

Main indicators for Fraud tolerance: How justifiable those actions are |

(V198) Claiming government benefits to which you are not entitled (on the scale from 1 (Never) to 10 (Always)) |

(V199) Avoiding a fare on public transport (on the scale from 1 (Never) to 10 (Always)) |

(V201) Cheating on taxes if you have a chance (on the scale from 1 (Never) to 10 (Always)) |

Additional indicators of Fraud tolerance for Robustness test: How justifiable those actions are |

(V200) Stealing property (on the scale from 1 (Never) to 10 (Always)) |

(V202) Someone accepting a bribe in the course of their duty (on the scale from 1 (Never) to 10 (Always)) |

Self-enhancing orientation |

(V71R) It is important to this person to be rich; to have a lot of money and expensive things (on the scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me)) |

(V73R) It is important to this person to have a good time; to "spoil" oneself (on the scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me)) |

(V75R) Being very successful is important to this person; to have people recognize one’s achievements (on the scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me)) |

(V76R) Adventure and taking risks are important to this person; to have an exciting life (on the scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me)) |

Self-transcending/communal orientation |

(V74R) It is important to this person to do something for the good of society (on the scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me)) |

(V78R) Looking after the environment is important to this person; to care for nature and save life resources (on the scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me)) |

Locus of Control (on the scale from 1 (No choice at all) to 10 (A great deal of choice) |

(V55) Some people feel they have completely free choice and control over their lives, while other people feel that what they do has no real effect on what happens to them |

Beliefs in Hard Work |

(V99R) Attitudes to competition (on the scale from 10 (Competition is good) to 1 (Competition is harmful)) |

(V100R) Hard Work and Success (on the scale from 10 (Hard work brings success in the long run) to 1 (it is all about connections and luck)) |

Gender Bias |

(V51R) On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do (on the scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree)) |

(V52R) A university education is more important for a boy than for a girl (on the scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree)) |

(V53R) On the whole, men make better business executives than women do (on the scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree)) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Knechel, W.R., Mintchik, N. Do Personal Beliefs and Values Affect an Individual’s “Fraud Tolerance”? Evidence from the World Values Survey. J Bus Ethics 177, 463–489 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04704-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04704-0