Abstract

Imagination and other forms of mental simulation allow us to live beyond the current immediate environment. Imagination that involves an experience of self further enables one to incorporate or utilize the contents of episodic simulation in a way that is of importance to oneself. However, the simulated self can be found in a variety of forms. The present study provides some empirical data to explore the various ways in which the self could be represented in observer-perspective imagination as well as the potential limits on such representations. In observer-perspective imagination, the point of view or perspective is dissociated from the location of one’s simulated body. We have found that while there are different ways to identify with oneself in an observer-perspective imagination, the identification is rarely dissociated from first-person perspective in imagination. Such variety and limits pave the way for understanding how we identify with ourselves in imagination. Our results suggest that the first-person perspective is a strong attractor for identification. The empirical studies and analysis in this paper demonstrate how observer-perspective episodic simulation serves as a special case for research on identification in mental simulation, and similar methods can be applied in the studies of memory and future thinking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, Paul (2014) has argued that there is a limit to the epistemic usefulness of imagination, particularly when it involves life-changing decisions, e.g., becoming a parent.

The definition of observer-perspective episodic simulation is debatable. Nigro & Neisser (1983) defined observer-perspective memory in the following way: “[i]n some memories, one has the perspective of an observer, seeing oneself ‘from the outside.’ In other memories, one sees the scene from one’s own perspective; the field of view in such memories corresponds to that of the original situation” (p. 467). In the context of imagination, the field- and observer-perspective phenomena cannot be defined by resorting to the correspondence to the original situation. The definition of observer-perspective imagination in this paper is therefore based on the location of origin of the perspective. In addition, the perspectival difference in vision is often adopted in the distinction between field and observer perspectives in the relevant empirical studies.

There may be other possibilities, but these are the most likely options. This is to some degree supported by our finding that almost no participants chose the option of “other” (see §4).

See Lin (2020) for an analysis of Fernández’s view and the ambiguity therein.

The sense of constitution used here is akin to “composition.”

Answer options 1 and 2 were presented in randomized order.

This answer option, as well as option 5 in the Identification question, were followed by text boxes that participants could use to explain their response.

Note that the target of our inquiry in this paper is self-experience in imagination including identification in experience. The options are therefore formulated in terms of what it feels like to imagine oneself from the observer perspective.

Answer options 1 and 2 were presented in randomized order.

One of these participants wrote: “Through my eyes, but [I] was aware of myself as like a shadow.” Another did not specify their answer.

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 171), the same pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 55% field, 24% observer, 21% switching, 1% other.

One of these participants wrote: “I was in the scene standing and observing myself run.” Another did not specify their answer.

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 131), the same pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 53% observer, 6% observed, 24% both, 15% switching, 2% other.

Focusing only on those participants who found it very easy to imagine the situation from the observer perspective (answering 1 or 2 on the Likert scale, n = 86), the same pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 55% observer, 6% observed, 24% both, 14% switching, 1% other.

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 132), the same pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 24% only field, 33% mostly field, 26% both equally, 14% mostly observer, 3% only observer. One-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test showed that participants thought that they more frequently imagine from a field perspective than from an observer perspective, W = 78, p < .001, with both median and modal response being “mostly through my own eyes.”

We do not calculate the correlation for the fourth option “In some other way” since only two participants chose this option.

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 189), the same pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 54% field, 25% observer, 20% switching, 0% other, 1% did not succeed in imagining.

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 162), the same pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 55% observer, 7% observed, 22% both, 9% switching, 2% other, 5% did not succeed in imagining the scene.

Focusing only on those participants who found it very easy to imagine the situation from the observer perspective (answering 1 or 2 on the Likert scale, n = 96), a similar pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample, except that this time no participant indicated that they did not succeed in imagining the scene from the observer perspective: 58% observer, 8% observed, 29% both, 3% switching, 1% other.

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 132), a similar pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 32% only field, 39% mostly field, 16% both equally, 12% mostly observer, 1% only observer. One-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test showed that participants thought that they more frequently imagine from a field perspective than from an observer perspective, W = 11.5, p < .001, with both median and modal response being “mostly through my own eyes.”

We do not calculate the correlation for the fourth option “In some other way” since no participants chose this option.

This correlation ceases to be statistically significant once participants who did not succeed in the imagination task are excluded (rs = .13, p = .074).

These results do not change if participants who report that they did not succeed in imagining the scene from the observer perspective are removed. Those who are more likely to imagine from the observer perspective still find the task easier (rs = -.40, p < .001) and there are no differences in reported felt certainty (rs = .05, p = .45).

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 162), the same pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 54% observer, 6% observed, 23% both, 6% switching, 1% other, 11% did not succeed in imagining the scene. Focusing only on those participants who found it very easy to imagine the situation from the observer perspective (answering 1 or 2 on the Likert scale, n = 96), a very similar pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample, except that this time no participant chose “In some other way”: 56% observer, 8% observed, 29% both, 2% switching, 4% did not succeed in imagining the scene.

Looking at relationships between dominant perspectives and the observer-perspective identification task, almost identical results are achieved using re-coded data as were achieved with the original data. The only significant correlations remain the same two: those who succeeded in imagining were more likely to dominantly imagine from an observer perspective (rs = .23, p < .001) and participants who chose response option “It feels like I am both the one observing the scene and the one inside the scene at the same time.” were more inclined to say that they dominantly imagine from the observer perspective (rs = .20, p = .004). All other four ps > .40.

Focusing only on those participants who felt highly certain of their response (≥ 90%, n = 70), a similar pattern of results can be observed as in the full sample: 67% observer, 1% observed, 19% both, 11% switching, 1% did not succeed in imagining the scene.

Note that percentages for Study 1 refer to the proportion of participants after excluding those who reported that they did not succeed in performing the task (3% were excluded in the observer-perspective imagination task and 14% were excluded in the identification task). Thus, percentages for Study 1 are slightly inflated if compared to Studies 2 and 3, where “I was not able to imagine the scene” was one of the response options.

The participants were requested to justify their responses in writing only in Study 2.

We thank reviewers for Synthese for pointing this out.

Sutton (2010) has mentioned an “external emotional perspective.” However, the definition of observer or external perspective in vision—involving “seeing oneself ‘from the outside’” (Nigro & Neisser, 1983)—cannot be applied to emotion, and thus the “externality” of an external emotional perspective might carry a different sense in the context of emotion.

Approximately half of the participants reported identifying with the one observing the scene in Studies 1, 2 and 3. In Study 3, after excluding those who chose “It feels like I am observing the scene from an external vantage point” because they indicated that they felt like they were the person doing the imagining in the real world, there were still more than one third of the participants who reported that they felt like they were the observers within the imagination.

Of course, our data cannot prove it is impossible to imagine from an observer perspective without phenomenologically identifying with the geometric origin of a visuospatial model of reality. What our data suggest, instead, is that—given how observer perspective is commonly elicited in the empirical literature (descriptions of field and observer perspectives in our study materials were adapted from Radvansky & Svob (2019) and Rice & Rubin (2009))—participants very rarely report that in successfully completing the task, they did not phenomenologically identify with the geometric origin of a visuospatial model of reality.

Note that UI and SL are conceptually distinct: While the former refers to what gives rise to the experience of “I am this,” the latter refers to the experiences of being located at or in a spatiotemporal point or space. Therefore, the current study on identification does not inform us about SL. To ascertain whether they are able to be dissociated empirically or whether UI is partially constituted by SL will require further studies.

References

Bermudez, J. L. (2013). Immunity to error through misidentification and past-tense memory judgements. Analysis, 73(2), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/ant002

Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2006). Emotion and vantage point in autobiographical memory. Cognition and Emotion, 20(8), 1193–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500371190

Blanke, O., & Metzinger, T. K. (2009). Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.003

Buckner, R. L., & Carroll, D. C. (2007). Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004

Callow, N., & Hardy, L. (2004). The relationship between the use of kinaesthetic imagery and different visual imagery perspectives. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410310001641449

Christian, B. M., Miles, L. K., Parkinson, C., & Macrae, C. N. (2013). Visual perspective and the characteristics of mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00699

Dana, A., & Gozalzadeh, E. (2017). Internal and external imagery effects on tennis skills among novices. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 124(5), 1022–1043. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031512517719611

Dilip, N. (2016). Imagination and the self. In A. Kind (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of philosophy of imagination (pp. 274–285). Routledge.

Fernández, J. (2014). Memory and immunity to error through misidentification. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 5(3), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-014-0193-4

Fernández, J. (2018). Observer memory and immunity to error through misidentification. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02050-3

Fernández, J. (2019). Memory: A self-referential account. Oxford University Press.

Gerrans, P. (2017). Painful memories. In K. Michaelian, D. Debus, & D. Perrin (Eds.), New directions in the philosophy of memory.Routledge.

Hamilton, A. (2009). Memory and self-consciousness: Immunity to error through misidentification. Synthese, 171(3), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-008-9318-6

Jacques, P. L., Carpenter, A. C., Szpunar, K. K., & Schacter, D. L. (2018). Remembering and imagining alternative versions of the personal past. Neuropsychologia, 110, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.06.015.

Jacques, P. L., Szpunar, K. K., & Schacter, D. L. (2017). Shifting visual perspective during retrieval shapes autobiographical memories. NeuroImage, 148, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.12.028.

Klein, S. B., & Nichols, S. (2012). Memory and the sense of personal identity. Mind, 121(483), 677–702. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzs080

Lin, Y.-T. (2018). Visual perspectives in episodic memory and the sense of self. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2196. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02196

Lin, Y.-T. (2020). The experience of being oneself in memory: Exploring sense of identity via observer memory. Review of Philosophy and Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-020-00468-8

McCarroll, C. J. (2018). Remembering from the outside: Personal memory and the perspectival mind. Oxford University Press.

McDermott, K. B., Wooldridge, C. L., Rice, H. J., Berg, J. J., & Szpunar, K. K. (2016). Visual perspective in remembering and episodic future thought. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1067237

Metzinger, T. K. (2004). Being no one: The self-model theory of subjectivity. The MIT Press.

Metzinger, T. (2013a). The myth of cognitive agency: Subpersonal thinking as a cyclically recurring loss of mental autonomy. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00931

Metzinger, T. K. (2013b). Why are dreams interesting for philosophers? The example of minimal phenomenal selfhood, plus an agenda for future research. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00746

Michaelian, K. (2020). Episodic memory is not immune to error through misidentification: Against Fernández. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02652-w

Nigro, G., & Neisser, U. (1983). Point of view in personal memories. Cognitive Psychology, 15(4), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(83)90016-6

Paul, L. A. (2014). Transformative experience. Oxford University Press.

Radvansky, G. A., & Svob, C. (2019). Observer memories may not be for everyone. Memory, 27(5), 647–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2018.1550093

Rice, H. J. (2010). Seeing where we’re at: A review of visual perspective and memory retrieval. In J. H. Mace (Ed.), The act of remembering (pp. 228–258). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444328202.ch10

Rice, H. J., & Rubin, D. C. (2009). I can see it both ways: First- and third-person visual perspectives at retrieval. Consciousness and Cognition, 18(4), 877–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2009.07.004

Rice, H. J., & Rubin, D. C. (2011). Remembering from any angle: The flexibility of visual perspective during retrieval. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(3), 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.10.013

Robinson, J. A., & Swanson, K. L. (1993). Field and observer modes of remembering. Memory, 1(3), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658219308258230

Schacter, D. L., & Addis, D. R. (2007). The ghosts of past and future. Nature, 445(7123), 27–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/445027a

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. C. (2007). The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07001975

Sutin, A. R., & Robins, R. W. (2008). When the “I” looks at the “Me”: Autobiographical memory, visual perspective, and the self. Consciousness and Cognition, 17(4), 1386–1397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.09.001

Sutton, J. (2010). Observer perspective and acentred memory: Some puzzles about point of view in personal memory. Philosophical Studies, 148(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-010-9498-z

Vendler, Z. (1979). Vicarious experience. Revue De Métaphysique Et De Morale, 84(2), 161–173.

Williams, B. (1973). Imagination and the self. Problems of the self: Philosophical papers 19561972 (pp. 26–45). Cambridge University Press.

Windt, J. M. (2010). The immersive spatiotemporal hallucination model of dreaming. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-010-9163-1

Wollheim, R. (1973). Imagination and identification. On art and the mind (pp. 54–83). Allen Land.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented during the virtual seminar hosted by the Centre for Philosophy of Memory, Université Grenoble Alpes. We would like to thank the audience at this event for feedback, especially Christopher McCarroll and John Sutton. We would also like to thank Hsin-Ping Wu for assistance, Simon Mussell for linguistic edits, and Po-Jang (Brown) Hsieh, Shen-yi Liao and three reviewers for their helpful comments. Ying-Tung Lin was supported by a grant from the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (108-2410-H-010-001-MY3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the topical collection "Imagination and its Limits", edited by Amy Kind and Tufan Kiymaz.

Appendix

Appendix

[Page 1; Introduction + initial imagination task]

After reading this paragraph, you will be asked to close your eyes and spend approximately ten seconds imagining that you are running on a deserted beach. Make sure to pay very close attention to what exactly you experience while imagining—you will later be asked some questions about your experience. After finishing the imagination task, you will be asked to proceed to the next page.

Now close your eyes and imagine yourself running on a deserted beach.

If you have completed the imagination task, proceed to the next page.

[Page 2; Questions for the initial imagination task + observer perspective identification task]

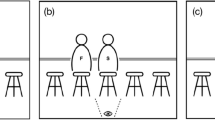

Most people imagine events in one of two ways. One way that people imagine an event is as if through their own eyes, from roughly the same viewpoint that it would be experienced. Another way that people imagine an event is as if from an external vantage point, where the imagined scene contains an image of themselves.

Question 1. When imagining yourself running on a deserted beach, did you imagine the scene as if through your own eyes or as if from an external vantage point?

[Answer options 1 and 2 in randomized order]

-

[1]

As if through my own eyes.

-

[2

As if from an external vantage point.

-

[3]

The perspective was switching between the two.

-

[4]

In some other way.

-

[5]

I was not able to imagine the scene.

Now, you will be once again asked to close your eyes and spend approximately ten seconds imagining that you are running on a deserted beach. Make sure to pay very close attention to what exactly you experience while imagining – you will later be asked some questions about your experience. After finishing the imagination task, you will be asked to proceed to the next page.

Please close your eyes and imagine for ten seconds that you are running on a deserted beach. This time specifically try to imagine the situation as if from an external vantage point.

If you have completed the imagination task, proceed to the next page.

[Page 3; Questions for the observer-perspective identification task]

Question 2. Now, when you think about your experience during the imagining from an external vantage point, which of the following descriptions is the most suitable description of your experience?

[Answer options 1 and 2 in randomized order]

-

[1]

It feels like I am observing the scene from an external vantage point.

-

[2]

It feels like I am inside the scene (i.e., the person running on a deserted beach).

-

[3]

It feels like I am both observing the scene and inside the scene at the same time.

-

[4]

It feels like I am switching between observing the scene and being inside the scene.

-

[5]

Other.

-

[6

I was not able to imagine the scene.

How certain are you of your response to Question 2 on a (0–100)% scale, with low numbers indicating that you are not sure and high numbers indicating that you are sure?

I am ___ % certain.

[Page 4: Follow-up question presented only to those who chose [1.] in Question 2]

Question 3. On the previous page, you chose an option: “It feels like I am observing the scene from an external vantage point.” Which of the following two descriptions captures what you had in mind when choosing this option?

[Answer options 1 and 2 in randomized order]

-

[1]

It feels like I am observing the scene from an external vantage point but not part of the imagination (i.e., it feels like I am the person doing the imagining in the real world).

-

[2]

It feels like I am observing the scene from an external vantage point but still part of the imagination (i.e., it feels like I am an observer in the imagination).

-

[3]

Other, explain.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, YT., Dranseika, V. The variety and limits of self-experience and identification in imagination. Synthese 199, 9897–9926 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03230-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03230-4