Abstract

Third-party punishment (TPP) has been shown to be an effective mechanism for maintaining human cooperation. However, it is puzzling how third-party punishment can be maintained, as punishers take on personal costs to punish defectors. Although there is evidence that punishers are preferred as partners because third-party punishment is regarded by bystanders as a costly signal of trustworthiness, other studies show that this signaling value of punishment can be severely attenuated because third-party helping is viewed as a stronger signal of trustworthiness than third-party punishment. Third-party helpers donate their payoffs to victims of defection in games instead of punishing defectors as third-party punishers do. Then, under what circumstances can third-party punishment be maintained by costly signaling when helping is also present? We show that punishers are preferred over helpers by fourth-party individuals as their delegates to deter potential exploitation. This suggests that costly signaling can facilitate the maintenance of third-party punishment in partner choice with delegation interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data are available as supplementary information.

Notes

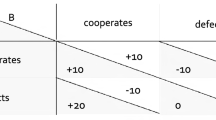

For example, Player 4 decides to send Player 3 (who chooses to punish) X RMB yuan, send Player 3 (who chooses to help) Y RMB yuan, and send Player 3 (who chooses to do nothing) Z RMB yuan. If Player 4 is paired with Player 3, who chose to punish, then Player 3 will get 3X RMB yuan.

The amounts entrusted to the third-party players were not normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk’s test (p < 0.05). Thus, we performed nonparametric tests to analyze the data. Since the analysis involved multiple comparisons, we also used the FDR correction procedure to avoid inappropriately increasing the number of null hypotheses that are wrongly rejected.

The amounts offered to the third-party players were not normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk’s test (p < 0.05). Thus, we performed nonparametric tests to analyze the data.

A novel solution for conducting such an experiment without deception comes from Jordan et al. (2016), but the cost of such a design is that there are no third-party helpers in the experiment. Since the comparison of third-party helpers and punishers is of interest, we cannot use their method to avoid deception.

References

Abbink, K., Gangadharan, L., Handfield, T., & Thrasher, J. (2017). Peer punishment promotes enforcement of bad social norms. Nature Communications, 8(1), 1–8.

Alexander, R. D. (1987). The biology of moral systems. Aldine de Gruyter.

Andreoni, J., & Gee, L. K. (2012). Gun for hire: Delegated enforcement and peer punishment in public goods provision. Journal of Public Economics, 96(11–12), 1036–1046.

Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, W. D. (1981). The evolution of cooperation. Science, 211(4489), 1390–1396.

Balafoutas, L., Grechenig, K., & Nikiforakis, N. (2014). Third-party punishment and counter-punishment in one-shot interactions. Economics Letters, 122(2), 308–310.

Barclay, P. (2006). Reputational benefits for altruistic punishment. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27(5), 325–344.

Barclay, P. (2011). Competitive helping increases with the size of biological markets and invades defection. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 281, 47–55.

Barclay, P. (2012). Proximate and ultimate causes of punishment and strong reciprocity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35(1), 16–17.

Barclay, P. (2013). Strategies for cooperation in biological markets, especially for humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34, 164–175.

Barclay, P., & Willer, R. (2007). Partner choice creates competitive altruism in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences, 274(1610), 749–753.

Bird, R. B., & Smith, E. A. (2005). Signaling theory, strategic interaction, and symbolic capital. Current Anthropology, 46(2), 221–248.

Boehm, C. (2012). Moral origins: The evolution of virtue, altruism, and shame. Basic Books.

Boyd, R., Gintis, H., & Bowles, S. (2010). Coordinated punishment of defectors sustains cooperation and can proliferate when rare. Science, 328(5978), 617–620.

Buckholtz, J. W., Asplund, C. L., Dux, P. E., Zald, D. H., Gore, J. C., Jones, O. D., & Marois, R. (2008). The neural correlates of third-party punishment. Neuron, 60(5), 930–940.

Chavez, A. K., & Bicchieri, C. (2013). Third-party sanctioning and compensation behavior: Findings from the ultimatum game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39, 268–277.

Choy, A., Hamman, J. R., King, R. R., & Weber, R. (2016). Delegated bargaining in a competitive agent market: An experimental study. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 2, 22–35.

Dalmia, P. (2019). Strategic delegation and fairness in bargaining. Working Paper.

de Quervain, D. J., Fischbacher, U., Treyer, V., Schellhammer, M., Schnyder, U., Buck, A., & Fehr, E. (2004). The neural basis of altruistic punishment. Science, 305(5688), 1254–1258.

Delton, A. W., & Krasnow, M. M. (2017). The psychology of deterrence explains why group membership matters for third-party punishment. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(6), 734–743.

dos Santos, M., Rankin, D. J., & Wedekind, C. (2011). The evolution of punishment through reputation. Proceedings of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences, 278(1704), 371–377.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism. Nature, 425(6960), 785–791.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004a). Social norms and human cooperation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(4), 185–190.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004b). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 63–87.

Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., & Gachter, S. (2002). Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms. Human Nature, 13(1), 1–25.

Fehr, E., & Gachter, S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature, 415(6868), 137–140.

Fershtman, C., & Gneezy, U. (2001). Strategic delegation: An experiment. RAND Journal of Economics, 32(2), 352–368.

Fershtman, C., Judd, K. L., & Kalai, E. (1991). Observable contracts: Strategic delegation and cooperation. International Economic Review, 32(3), 551–559.

Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J. L., Savin, N. E., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 6(3), 347–369.

Gintis, H., Smith, E. A., & Bowles, S. (2001). Costly signaling and cooperation. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 213(1), 103–119.

Grafen, A. (1990). Biological signals as handicaps. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 144(4), 517–546.

Gurerk, O., Irlenbusch, B., & Rockenbach, B. (2006). The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science, 312(5770), 108–111.

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7(1), 1–16.

Hauert, C., De Monte, S., Hofbauer, J., & Sigmund, K. (2002). Volunteering as red queen mechanism for cooperation in public goods games. Science, 296(5570), 1129–1132.

Hauert, C., Traulsen, A., Brandt, H., Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (2007). Via freedom to coercion: The emergence of costly punishment. Science, 316(5833), 1905–1907.

Hertwig, R., & Ortmann, A. (2001). Experimental practices in economics: A methodological challenge for psychologists? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(3), 383–403.

Horita, Y. (2010). Punishers may be chosen as providers but not as recipients. Letters on Evolutionary Behavioral Science, 1(1), 6–9.

Houser, D., & Xiao, E. (2010). Inequality-seeking punishment. Economics Letters, 109(1), 20–23.

Janssen, M. A., & Bushman, C. (2008). Evolution of cooperation and altruistic punishment when retaliation is possible. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 254(3), 541–545.

Johnson, A. W., & Earle, T. K. (2000). The evolution of human societies: from foraging group to agrarian state (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press.

Johnstone, R. A. (1995). Sexual selection, honest advertisement and the handicap principle : Reviewing the evidence. Biological Reviews, 70(1), 1–65.

Jordan, J. J., Hoffman, M., Bloom, P., & Rand, D. G. (2016). Third-party punishment as a costly signal of trustworthiness. Nature, 530(7591), 473–476.

Jordan, J. J., & Rand, D. G. (2017). Third-party punishment as a costly signal of high continuation probabilities in repeated games. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 421, 189–202.

Kamei, K. (2020). Group size effect and over-punishment in the case of third party enforcement of social norms. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 175, 395–412.

Katz, M. L. (1991). Game-playing agents: Unobservable contracts as precommitments. The RAND Journal of Economics, 22(3), 307–328.

Kockesen, L., & Ok, E. A. (2004). Strategic delegation by unobservable incentive contracts. The Review of Economic Studies, 71(2), 397–424.

Krasnow, M. M., Delton, A. W., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2016). Looking under the hood of third-party punishment reveals design for personal benefit. Psychological Science, 27(3), 405–418.

Leibbrandt, A., & López-Pérez, R. (2011). The dark side of altruistic third-party punishment. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(5), 761–784.

Liu, J., Riyanto, Y. E., & Zhang, R. (2020). Firing the right bullets: Exploring the effectiveness of the hired-gun mechanism in the provision of public goods. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 170, 222–243.

Marlowe, F. W., Berbesque, J. C., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., Cardenas, J. C., Ensminger, J., Gurven, M., Gwako, E., & Henrich, J. (2008). More ‘altruistic’punishment in larger societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275(1634), 587–592.

Mayr, E. (1963). Animal species and evolution. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Nelissen, R. M. A. (2008). The price you pay: Cost-dependent reputation effects of altruistic punishment. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(4), 242–248.

Nelissen, R. M. A., & Zeelenberg, M. (2009). Moral emotions as determinants of third-party punishment: Anger, guilt, and the functions of altruistic sanctions. Judgment and Decision Making, 4(7), 543–553.

Nikiforakis, N., & Mitchell, H. (2014). Mixing the carrots with the sticks: Third party punishment and reward. Experimental Economics, 17(1), 1–23.

Noë, R., & Hammerstein, P. (1994). Biological markets: Supply and demand determine the effect of partner choice in cooperation, mutualism and mating. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 35, 1–11.

Noë, R., & Hammerstein, P. (1995). Biological markets. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 10, 336–339.

Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (1998a). The dynamics of indirect reciprocity. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 194(4), 561–574.

Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (1998b). Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature, 393(6685), 573–577.

Ohtsuki, H., Iwasa, Y., & Nowak, M. A. (2009). Indirect reciprocity provides only a narrow margin of efficiency for costly punishment. Nature, 457(7225), 79–82.

Peysakhovich, A., Nowak, M. A., & Rand, D. G. (2014). Humans display a “cooperative phenotype” that is domain general and temporally stable. Nature Communications, 5, 4939.

Raihani, N. J., & Bshary, R. (2015a). The reputation of punishers. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 30(2), 98–103.

Raihani, N. J., & Bshary, R. (2015b). Third-party punishers are rewarded, but third-party helpers even more so. Evolution, 69(4), 993–1003.

Riedl, K., Jensen, K., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2012). No third-party punishment in chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(37), 14824–14829.

Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Harvard University Press.

Schotter, A., Wei, Z., & Snyder, B. (2000). Bargaining Through Agents: An Experimental Study of Delegation and Commitment. Games and Economic Behavior, 30, 248–292.

Scott-Phillips, T. C., Dickins, T. E., & West, S. A. (2011). Evolutionary theory and the ultimate-proximate distinction in the human behavioral sciences. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 38–47.

Smith, E. A., & Bird, R. B. (2005). Costly signaling and cooperative behavior. In H. Gintis, S. Bowles, R. Boyd, E. Fehr (Eds.) Moral sentiments and material interests: on the foundations of cooperation in economic life (pp. 115–148). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Smith, E. A., & Bird, R. L. (2000). Turtle hunting and tombstone opening public generosity as costly signaling. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21(4), 245–261.

Smith, E. A., Bird, R. B., & Bird, D. W. (2003). The benefits of costly signaling: Meriam turtle hunters. Behavioral Ecology, 14(1), 116–126.

Spence, A. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 355–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882010

Sutter, M., Haigner, S., & Kocher, M. G. (2010). Choosing the carrot or the stick? Endogenous institutional choice in social dilemma situations. The Review of Economic Studies, 77(4), 1540–1566.

Tan, F., & Xiao, E. (2018). Third-party punishment: Retribution or deterrence? Journal of Economic Psychology, 67, 34–46.

Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35–57.

Veblen, T. (1899). The theory of the leisure class. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Yang, C.-L., Zhang, B., Charness, G., Li, C., & Lien, J. W. (2018). Endogenous rewards promote cooperation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(40), 9968–9973.

Ye, H., Tan, F., Ding, M., Jia, Y., & Chen, Y. (2011). Sympathy and punishment: Evolution of cooperation in public goods game. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 14(14), 20.

Zahavi, A. (1995). Altruism as a handicap - the limitations of kin selection and reciprocity. Journal of Avian Biology, 26(1), 1–3.

Zahavi, A., Zahavi, A. (1997). The handicap principle: A missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zhang, B., Li, C., De Silva, H., Bednarik, P., & Sigmund, K. (2014). The evolution of sanctioning institutions: An experimental approach to the social contract. Experimental Economics, 17(2), 285–303.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 72073117), the Key Projects of Zhejiang Soft Science Research Program (Grant number: 2021C25041), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LQ20G010007) and MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (Project No. 19YJC630087). We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All the procedures performed in this study were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Corresponding authors: Jun Luo, He Niu, Hang Ye.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix

A: Experiment instructions

2.1 Experiment 1

In experiment 1, the dictator, recipient, third party, and fourth party are labeled as “Player 1”, “Player 2”, “Player 3”, and “Player 4”. The third party and the fourth party each receive instructions about the experiment, which is slightly different.

2.2 For the fourth party (Player 4):

This is a game in which you might earn a bonus. You are Player 4. You will only play in game B and will NOT be a part of game A. However, we would like you to read about and understand both games.

2.3 For the third party (Player 3):

This is a game in which you might earn a bonus. You are Player 3. You will play two games, game A and game B. We would like you to read about and understand both games before you play game A.

2.4 For both the third party (Player 3) and the fourth party (Player 4):

Game A

Game A has three players: Player 1, Player 2, and Player 3.

In this game:

A sum of 20 RMB yuan has been provisionally allocated to Player 1 and Player 2.

Player 1 can decide how much of the money each person is to receive.

Player 1 has two choices:

-

– DO share: give 10 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 10 RMB yuan).

-

Do NOT share: give 0 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 20 RMB yuan).

Afterwards, Player 3 is given 25 RMB yuan.

If Player 1 chose not to share with Player 2, Player 3 has three choices:

-

(1) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income is reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income is increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) If Player 1 chose not to share, do nothing.

Game B

4.1 Game B has two players: Player 3 and Player 4

In game B:

-

Player 4 starts with 40 RMB yuan.

-

Player 4 then chooses how much money to send to Player 3.

-

Any money Player 4 sends to Player 3 is tripled (If Player 4 sends K, Player 3 will receive 3 K).

-

Player 3 then chooses how much money to return to Player 4.

If Player 4 sends K and Player 3 returns M, then Player 4 will earn 40-K + M. Player 3 will earn 3 K-M.

Income structure

5.1 Player 3

The system will randomly choose between the experiment A income and the experiment B income as Player 3’s experiment income.

5.2 Player 4

The income in experiment B.

Please answer the following questions to ensure that you understand this instruction. You MUST answer ALL questions correctly to participate in the games.

Q1

In experiment A, when Player 1 chooses to give Player 1 zero RMB yuan and keeps 20 RMB yuan, Player 3 has three choices.

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, the experiment A incomes of Player 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

If Player 3 decides to do nothing, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

The following incomes do not include the appearance fee.

(1) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 25 RMB yuan.

(2) Player 1 has 15 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

(3) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 5 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

Q2

If Player 3 is first endowed with 25 RMB yuan in experiment A and has 20 RMB yuan after making the experiment A decision and the experiment B income of Player 3 is 20 RMB yuan, then the final experiment income of Player 3 is ______RMB yuan? (excluding the appearance fee).

Q3

If a Player 3’s experiment A income is 20 RMB yuan and experiment B income is 15 RMB yuan, which of the following statements is true about the experiment income of this Player 3? (excluding the appearance fee).

( ) The experiment income of Player 3 is 35 RMB yuan.

( ) The experiment income of Player 3 is 15 RMB yuan or 20 RMB yuan, and the final income is selected by Player 3 him- or herself.

( ) The experiment income of Player 3 is 15 RMB yuan or 20 RMB yuan, and the final income is randomly selected by the system.

Q4

Player 4 decides to send Player 3 (who chooses to punish in experiment A) X RMB yuan, send Player 3 (who chooses to help in experiment A) Y RMB yuan, and send Player 3 (who chooses to do nothing in experiment A) Z RMB yuan. If Player 4 paired with Player 3 who chose to punish in experiment A, then how much money will Player 3 get (after tripling)?

( ) Player 3 gets 3X RMB yuan.

( ) Player 3 gets 3Y RMB yuan.

( ) Player 3 gets X RMB yuan.

Q5

In experiment B, if Player 4 sends Player 3 40 RMB yuan and Player 3 decides to return Player 4 50%, what are the incomes of Player 3 and 4 in experiment B?

( ) Player 4 gets 20 RMB yuan, and Player 3 gets 60 RMB yuan.

( ) Player 4 gets 30 RMB yuan, and Player 3 gets 50 RMB yuan.

( ) Player 4 gets 60 RMB yuan, and Player 3 gets 60 RMB yuan.

Q6

In experiment B, which decision will make Player 4 get the highest income?

( ) It depends upon how much Player 3 decides to return to Player 4.

( ) Player 4 decides to send 40 RMB yuan to Player 3.

( ) Player 4 decides to send 0 RMB yuan for Player 3.

Correct answers: Q1) 2, 3, 1; Q2) 20; Q3) the experiment income of Player 3 is 15 RMB yuan or 20 RMB yuan, and the final income is randomly selected by the system; Q4) Player 3 gets 3X RMB yuan; Q5) Player 4 gets 60 RMB yuan, and Player 3 gets 60 RMB yuan; Q6) it depends upon how much Player 3 decides to return to Player 4.

Player 3 Game A choice

You have received 25 RMB yuan. What would you like to do if Player 1 does not share?

NOTE: Player 4 will be told your choice in game A before deciding how much money to send to you.

-

(1) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income will be reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income will be increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) I would like to do nothing.

Player 4

How much money would you like to send to Player 3, who in game A…

– Chose to punish Player 1?

– Chose to help Player 2?

– Chose to do nothing? (Unit: RMB yuan).

NOTE: You can base your decision on Player 3’s choice in game A.

13.2 Experiment 2

In experiment 2, the dictator, recipient, third party, and fourth party are labeled as “Player 1”, “Player 2”, “Player 3”, and “Player 4”. The third party and the fourth party each receive instructions about the experiment, which is slightly different.

13.3 For the fourth party (Player 4):

This is a game in which you might earn a bonus. You are Player 4. You will only play in game B and will NOT be a part of game A. However, we would like you to read about and understand both games.

13.4 For the third party (Player 3):

This is a game in which you might earn a bonus. You are Player 3. You will play two games, game A and game B. We would like you to read about and understand both games before you play game A.

13.5 For both the third party (Player 3) and the fourth party (Player 4):

Game A

Game A has three players: Player 1, Player 2, and Player 3.

In this game:

A sum of 20 RMB yuan has been provisionally allocated to Player 1 and Player 2.

Player 1 can decide how much of the money each person is to receive.

Player 1 has two choices:

– DO share: give 10 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 10 RMB yuan).

– Do NOT share: give 0 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 20 RMB yuan).

Afterwards, Player 3 is given 25 RMB yuan.

If Player 1 chose not to share with Player 2, Player 3 has three choices:

-

(1) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income is reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income is increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) If Player 1 chose not to share, do nothing.

Game B

Game B has two players: Player 3 and Player 4.

In game B:

A sum of 40 RMB yuan has been provisionally allocated to Player 3 and Player 4.

Player 4 will be informed of Player 3’s choice in game A.

Player 4 then chooses how much money to offer to Player 3.

Player 3 then chooses to accept or reject this offer. If Player 3 accepts, Player 3 gets the offered amount and Player 4 keeps the rest.

However, if Player 3 rejects the offer, both Player 3 and Player 4 get nothing.

Income structure

Player 3.

The system will randomly choose between the experiment A income and the experiment B income as Player 3’s experiment income.

Player 4.

The income in experiment B.

Please answer the following questions to ensure that you understand this instruction. You MUST answer ALL questions correctly to participate in the games.

Q1

In experiment A, when Player 1 chooses to give Player 1 zero RMB yuan and keeps 20 RMB yuan, Player 3 has three choices.

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, the experiment A incomes of Player 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

If Player 3 decides to do nothing, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

The following incomes do not include the appearance fee.

(1) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 25 RMB yuan.

(2) Player 1 has 15 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

(3) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 5 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

Q2

If Player 3 is first endowed with 25 RMB yuan in experiment A and has 20 RMB yuan after making the experiment A decision and the experiment B income of Player 3 is 20 RMB yuan, then the final experiment income of Player 3 is ______RMB yuan? (excluding the appearance fee).

Q3

If a Player 3’s experiment A income is 20 RMB yuan and experiment B income is 15 RMB yuan, which of the following statements is true about the experiment income of this Player 3? (excluding the appearance fee).

() The experiment income of Player 3 is 35 RMB yuan.

() The experiment income of Player 3 is 15 RMB yuan or 20 RMB yuan, and the final income is selected by Player 3 him- or herself.

() The experiment income of Player 3 is 15 RMB yuan or 20 RMB yuan, and the final income is randomly selected by the system.

Q4

Which of the following statements is correct?

( ) Player 4 is first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer.

( ) Player 4 is NOT first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer.

Q5

In experiment B, which decision will make Player 4 obtain the highest income?

( ) It depends upon whether Player 3 decides to accept Player 4’s offer.

( ) Player 4 decides to offer 40 RMB yuan to Player 3.

( ) Player 4 decides to offer 0 RMB yuan to Player 3.

Correct answers: Q1) 2, 3, 1; Q2) 20; Q3) the experiment income of Player 3 is 15 RMB yuan or 20 RMB yuan, and the final income is randomly selected by the system; Q4) Player 4 is first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer; Q5) it depends upon whether Player 3 decides to accept Player 4’s offer.

Player 3 Game A choice

You have received 25 RMB yuan. What would you like to do if Player 1 does not share?

NOTE: Player 4 will be told your choice in game A before deciding how much money to send to you.

-

(1) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income will be reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income will be increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) I would like to do nothing.

Player 4

Player 3 chose to punish Player 1/help Player 2 /do nothing in game A.

How much money would you like to offer to this Player 3? (Unit: RMB yuan).

NOTE: You can base your decision on Player 3’s choice in game A.

Player 3 Game B choice

Player 4 decides to offer you ( ) of 40. Do you accept the amount offered?

( ) Accept ( ) Reject.

Experiment 3 known group

In experiment 3, the dictator, recipient, third party, fourth-party principal and fourth-party proposer are labeled as “Player 1”, “Player 2”, “Player 3”, “Player 4”, and “Player 5”.

25.1 For the fourth-party principal (Player 4):

This is a game in which you might earn a bonus. You are Player 4. You will only play in game B and will NOT be a part of game A. However, we would like you to read about and understand both games.

Game A

Game A has three players: Player 1, Player 2, and Player 3.

In this game:

A sum of 20 RMB yuan has been provisionally allocated to Player 1 and Player 2.

Player 1 can decide how much of the money each person is to receive.

Player 1 has two choices:

– DO share: give 10 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 10 RMB yuan).

– Do NOT share: give 0 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 20 RMB yuan).

Afterwards, Player 3 is given 25 RMB yuan.

If Player 1 chose not to share with Player 2, Player 3 has three choices:

-

(1) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income is reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income is increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) If Player 1 chose not to share, do nothing.

Game B

Game B has 3 players: Player 3, Player 4 and Player 5.

In game B:

According to the choices of Player 3 in experiment A, Player 4 could choose one kind of Player 3 on his/her behalf to participate in game B.

Then, a sum of 60 RMB yuan is provisionally allocated to Player 4, the selected Player 3 and Player 5.

Player 5 first will be informed about Player 3’s choice in game A and then choose how much money to offer to Player 3 and 4.

Player 3 then chooses to accept or reject this offer.

If Player 3 accepts, Players 3 and 4 get the offered amount (Players 3 and 4 will split the amount equally), and Player 5 keeps the rest.

However, if Player 3 rejects, Players 3, 4 and 5 get nothing.

NOTE: Player 5 is first informed about the delegate’s first-stage choice before he/she makes the offer.

Income structure

Player 3.

The system will randomly choose between the experiment A income and the experiment B income as Player 3’s experiment income.

Player 4.

The income in experiment B.

Player 5.

The income in experiment B.

Please answer the following questions to ensure that you understand this instruction. You MUST answer ALL questions correctly to participate in the games.

Q1

In experiment A, when Player 1 chooses to give Player 1 zero RMB yuan and keeps 20 RMB yuan, Player 3 has three choices.

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, the experiment A incomes of Player 1, 2, and 3 are ().

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ().

If Player 3 decides to do nothing, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ().

The following incomes do not include the appearance fee.

(1) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 25 RMB yuan.

(2) Player 1 has 15 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

(3) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 5 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

Q2

If Player 3 is first endowed with 25 RMB yuan in experiment A and has 20 RMB yuan after making the experiment A decision and the experiment B income of Player 3 is 20 RMB yuan, then the final experiment income of Player 3 is ______RMB yuan? (excluding the appearance fee).

Q3

Which of the following statements is correct?

( ) Player 5 is first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer.

( ) Player 5 is NOT first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer.

Q4

In experiment B, if Players 3 and 4 are offered a total of 40 RMB yuan and Player 3 accepts the offer, what are the experiment B incomes of Players 3, 4, and 5?

( ) Player 3: 20 RMB yuan, Player 4: 20 RMB yuan, Player 5: 20 RMB yuan.

( ) Player 3: 30 RMB yuan, Player 4: 10 RMB yuan, Player 5: 20 RMB yuan.

( ) Player 3: 20 RMB yuan, Player 4: 20 RMB yuan, Player 5: 40 RMB yuan.

Correct answers: Q1) 2, 3, 1; Q2) 20; Q3) Player 5 is first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer; Q4) Player 3: 20 RMB yuan, Player 4: 20 RMB yuan, Player 5: 20 RMB yuan.

Player 3 Game A choice

You have received 25 RMB yuan. What would you like to do if Player 1 does not share?

-

(1) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income will be reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income will be increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) I would like to do nothing.

Player 4

NOTE! Player 5 will observe your choice and make subsequent decisions based on your choices.

Which of the following types of Player 3 do you wish to choose to complete experiment B for you?

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in experiment A to punish Player 1.

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in experiment A to compensate Player 2.

( ) Choose the player who does nothing in experiment A.

Player 5

Player 4 has chosen the player who punished Player 1/helped Player 2 /did nothing in game A.

How much money would you like to offer to this Player 3 and Player 4? (Unit: RMB yuan).

Player 3 Game B choice

Player 4 decides to offer you and Player 4 ( ) of 40 RMB yuan. Do you accept the amount offered? (You and Player 4 will split the amount equally).

( ) Accept ( ) Reject.

Experiment 3 unknown group

In experiment 3, the dictator, recipient, third party, fourth-party principal and fourth-party proposer are labeled as “Player 1”, “Player 2”, “Player 3”, “Player 4”, and “Player 5”.

37.1 For the fourth-party principal (Player 4):

This is a game in which you might earn a bonus. You are Player 4. You will only play in game B and will NOT be a part of game A. However, we would like you to read about and understand both games.

Game A

Game A has three players: Player 1, Player 2, and Player 3.

In this game:

A sum of 20 RMB yuan has been provisionally allocated to Player 1 and Player 2.

Player 1 can decide how much of the money each person is to receive.

Player 1 has two choices:

– DO share: give 10 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 10 RMB yuan).

– Do NOT share: give 0 RMB yuan to Player 2 (and keep 20 RMB yuan).

Afterwards, Player 3 is given 25 RMB yuan.

If Player 1 chose not to share with Player 2, Player 3 has three choices:

-

(1) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income is reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) If Player 1 chose not to share, pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income is increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) If Player 1 chose not to share, do nothing.

Game B

Game B has 3 players: Player 3, Player 4 and Player 5.

In game B:

According to the choices of Player 3 in experiment A, Player 4 could choose one kind of Player 3 on his/her behalf to participate in game B.

Then, a sum of 60 RMB yuan is provisionally allocated to Player 4, the selected Player 3 and Player 5.

Player 5 then chooses how much money to offer to Players 3 and 4.

Player 3 then chooses to accept or reject this offer.

If Player 3 accepts, Players 3 and 4 get the offered amount (Players 3 and 4 will split the amount equally), and Player 5 keeps the rest.

However, if Player 3 rejects, Players 3, 4 and 5 get nothing.

NOTE: Player 5 is NOT first informed about the delegate’s first-stage choice before he/she makes the offer.

Income structure

40.1 Player 3

The system will randomly choose between the experiment A income and the experiment B income as Player 3’s experiment income.

40.2 Player 4

The income in experiment B.

40.3 Player 5

The income in experiment B.

Please answer the following questions to ensure that you understand this instruction. You MUST answer ALL questions correctly to participate in the games.

Q1

In experiment A, when Player 1 chooses to give Player 1 zero RMB yuan and keeps 20 RMB yuan, Player 3 has three choices.

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, the experiment A incomes of Player 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

If Player 3 decides to spend 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

If Player 3 decides to do nothing, the experiment A incomes of Players 1, 2, and 3 are ( ).

The following incomes do not include the appearance fee.

(1) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 25 RMB yuan.

(2) Player 1 has 15 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 0 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

(3) Player 1 has 20 RMB yuan, Player 2 has 5 RMB yuan, and Player 3 has 20 RMB yuan.

Q2

If Player 3 is first endowed with 25 RMB yuan in experiment A and has 20 RMB yuan after making the experiment A decision and the experiment B income of Player 3 is 20 RMB yuan, then the final experiment income of Player 3 is ______RMB yuan? (excluding the appearance fee).

Q3

Which of the following statements is correct?

( ) Player 5 is first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer.

( ) Player 5 is NOT first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer.

Q4

In experiment B, if Players 3 and 4 are offered a total of 40 RMB yuan and Player 3 accepts the offer, what are the experiment B incomes of Players 3, 4, and 5?

( ) Player 3: 20 RMB yuan, Player 4: 20 RMB yuan, Player 5: 20 RMB yuan.

( ) Player 3: 30 RMB yuan, Player 4: 10 RMB yuan, Player 5: 20 RMB yuan.

( ) Player 3: 20 RMB yuan, Player 4: 20 RMB yuan, Player 5: 40 RMB yuan.

Correct answers: Q1) 2, 3, 1; Q2) 20; Q3) Player 5 is NOT first informed about Player 3’s choice in experiment A before he/she makes the offer; Q4) Player 3: 20 RMB yuan, Player 4: 20 RMB yuan, Player 5: 20 RMB yuan.

Player 3 Game A choice

You have received 25 RMB yuan. What would you like to do if Player 1 does not share?

-

(1) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1, and Player 1’s income will be reduced by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(2) I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2, and Player 2’s income will be increased by 5 RMB yuan.

-

(3) I would like to do nothing.

Player 4

NOTE! Player 5 is NOT first informed about the delegate’s first-stage choice before he/she makes the offer.

Which of the following types of Player 3 do you wish to choose to complete experiment B for you?

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in experiment A to punish Player 1.

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in experiment A to compensate Player 2.

( ) Choose the player who does nothing in experiment A.

Player 5

Player 4 has chosen the player 3.

How much money would you like to offer to this Player 3 and Player 4? (Unit: RMB yuan).

Player 3 Game B choice

Player 4 decides to offer you and Player 4 () of 40 RMB yuan. Do you accept the amount offered? (You and Player 4 will split the amount equally).

( ) Accept ( ) Reject.

B: Results

B1: Experiment 1

(1) Fourth-party trust questionnaire

After the TG, the fourth-party players were asked “How much do you trust the helper/punisher/player who did nothing (PDN)?” using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from “Completely distrust” to “Completely trust”.

The Friedman test showed differences in fourth parties’ trust in third parties. (χ2 (2) = 41.097, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.623) Fourth-party players thought the helpers (mean rating = 7.03, S.D. = 2.365) were more trustworthy than the punishers (mean rating = 5.39, S.D. = 2.597) [Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.019] and the PDN (mean rating = 2.52, S.D. = 2.386) [Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.002]. Furthermore, fourth-party players trusted punishers more than the PDN [Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.002]. Partial questionnaire data were not recorded during Experiment 1. We collected data from 33 fourth-party players (of 43 players) in the trust questionnaire.

(2) Third-party and fourth-party partner choice questionnaire

After the experiment, the third-party players indicated the type of player with whom they would prefer to play the TG if they were fourth-party players.

“If you were Player 4, which of the following types of players do you wish to choose to as Player 3 complete Experiment B with you?

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in Experiment A to punish Player 1.

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in Experiment A to compensate Player 2.

( ) Choose the player who did nothing in Experiment A.”

After the experiment, fourth-party players were asked about the player with whom they preferred to play the TG.

“Which of the following types of players do you wish to choose to complete Experiment B with you as Player 3?

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in Experiment A to punish Player 1.

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 in Experiment A to compensate Player 2.

( ) Choose the player who did nothing in Experiment A.”

E1: Chooser | Punishers (%) | Helpers (%) | PDN (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Third party | 18.60 | 53.49 | 27.91 |

95% CI | 6.49–30.72 | 37.96–69.02 | 13.94–41.87 |

Fourth party | 11.63 | 65.12 | 23.26 |

95% CI | 1.65–21.61 | 50.28–79.96 | 10.1–36.41 |

(a) The Chi-square test indicated the third-party players’ differential preferences for partners in the TG when they were in the fourth party’s position (n = 43, χ2 (2) = 8.419, p = 0.015, effect size = 0.313). The helpers were chosen more often (53.49%) than both the PDN (27.91%) and the punishers (18.60%).

(b) The Chi-square test showed fourth-party players’ differential preferences for partners in TG (n = 43, χ2 (2) = 20.419, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.487). Helpers (65.12%) were chosen more often than both PDN (23.26%) and punishers (11.63%).

(3) Third-party sending questionnaire

After the experiment, the third-party players indicated how much money they would send to different kinds of third-party players if they were fourth parties.

“If you were Player 4, how much money would you send to Player 3 who, in game A, …

– Chose to punish Player 1?

– Chose to help Player 2?

– Chose to do nothing? (Unit: RMB yuan)”.

The third-party players entrusted the most money to the helpers (mean money trusted = 22.56 RMB yuan, S.D. = 12.217), followed by the punishers (mean money trusted = 16.63 RMB yuan, S.D. = 12.758), and the PDN (mean money trusted = 9.88 RMB yuan, S.D. = 9.417).

A Friedman test showed differences in the amount sent to three types of trustees. The amounts sent varied significantly (χ2 (2) = 47.091, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.548). Pairwise comparisons revealed that the third-party players sent 14.83 more percentage points to the helpers than to the punishers (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.002). The third-party players sent 16.86 more percentage points to the punishers than to the PDN (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0. 003).

(4) The return of third-party players in trust game

Player 4 will decide how much to send to you. It is now your job to decide how much to return to Player 4.

Specifically, you will decide the percentage of money you would like to return.

For example, if you decide to return 10% of the money you receive…

– You will return 0 RMB yuan if Player 4 sends 0 RMB yuan (and you will receive 0 RMB yuan).

– You will return 3 RMB yuan if the sender sends 10 (and you will receive 27 RMB yuan).

What percentage would you like to return?

( )0% ( )10% ( )20% ( )30% ( )40% ( )50% ( )60% ( )70% ( )80% ( )90% ( )100%

A Kruskal–Wallis H test revealed that there were no significant differences in the amounts returned between three types of third-party players (χ2 (2) = 2.929, p = 0.23).

Punishers (%) | Helpers (%) | PDN (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Mean | 28.33 | 18.18 | 15 |

95% CI | 18.33–36.67 | 12.73–23.94 | 2.50–32.5 |

B2: Experiment 2

(1) Fourth-party offering questionnaire

After the experiment, the fourth-party players indicated how much money they would offer to different kinds of third-party players.

“How much money would you like to offer to Player 3 who, in game A,…

– Chose to punish Player 1?

– Chose to help Player 2?

– Chose to do nothing?” (Unit: RMB yuan).

The fourth-party players offered the most money to the punishers (mean money offered = 17.50 RMB yuan, S.D. = 5.470), followed by the helpers (mean money offered = 16.56 RMB yuan, S.D. = 5.980), and the PDN in the TPPG (mean money offered = 14.5 RMB yuan, S.D. = 6.362). Partial questionnaire data were not recorded during Experiment 2 (N = 90).

A Friedman test showed differences in the amount sent to three types of responders. The amounts offered varied significantly (χ2 (2) = 24.410, p < 0.001, n = 90, effect size = 0.136). Pairwise comparisons revealed that the fourth-party players offered 2.36 more percentage points to the punishers than to the helpers (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.192). The fourth-party players sent 5.14 more percentage points to the helpers than to the PDN (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0. 012).

(2) Third-party and fourth-party partner choice questionnaire

After the experiment, the third-party players indicated the player with whom they would prefer to play the UG if they were the fourth party.

“If you were Player 4, which of the following types of Player 3 do you wish to choose to complete Experiment B with you?

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 RMB yuan in Experiment A to punish Player 1.

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 RMB yuan in Experiment A to compensate Player 2.

( ) Choose the player who did nothing in experiment A.”

After the experiment, the fourth-party players indicated the player with whom they preferred to play the UG.

“Which of the following types of Player 3 do you wish to choose to complete Experiment B with you?

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 RMB yuan in Experiment A to punish Player 1.

( ) Choose the player who spent 5 RMB yuan in Experiment A to compensate Player 2.

( ) Choose the player who did nothing in Experiment A.”

E2: Chooser | Punishers (%) | Helpers (%) | PDN (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Third party | 12.26 | 64.15 | 23.58 |

95% CI | 5.92–18.61 | 54.87–73.43 | 15.37–31.8 |

Fourth party | 9.43 | 60.38 | 30.19 |

95% CI | 3.78–15.09 | 50.91–69.8 | 21.91–39.07 |

(a) The Chi-square test showed the third-party players’ differential preferences for partners in the UG when they were in the fourth party’s position (n = 106, χ2 (2) = 91.236, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.656). The helpers (64.15%) were chosen more often than both the PDN (23.58%) and the punishers (12.26%).

(b) The Chi-square test showed the fourth-party players’ differential preferences for partners in the UG (n = 106, χ2 (2) = 41.736, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.444). The helpers (60.38%) were chosen more often than both the PDN (30.19%) and the punishers (9.43%).

(3) Third-party choice in TPPG

“You have received 25 RMB yuan. What would you like to do if Player 1 does not share?

(1) Punishing: I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to punish Player 1 and reduce Player 1’s income by 5 RMB yuan.

(2) Helping: I would like to pay 5 RMB yuan to help Player 2 and increase Player 2’s income by 5 RMB yuan.

(3) Doing nothing: I would like to do nothing.”

The Chi-square test showed the third-party players’ different choices in the TPPG of Experiment 2 (n = 106, χ2 (2) = 13.717, p = 0.001, effect size = 0.254). Third-party players chose to do nothing (47.17%) more often than to help (34.91%) or punish (17.92%).

Furthermore, we analyzed the proportion of third-party players’ TPPG choices across experiments. The two multinomial probability distributions were not equal among the groups (χ2(2) = 23.789, p < 0.001, effect size = 0.282). Third-party players chose to help in Experiment 1 (76.74%) more than in Experiment 2 (34.91%, p < 0.001). Conversely, the third-party players chose to do nothing in Experiment 1 (9.30%) less than in Experiment 2 (47.17%, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the proportion of third-party players who chose to do nothing in the different experiments. (13.95% versus 17.92%), p = 0.557.

(4) Third party’s real benefits in the UG

Punishers | Helpers | PDN | |

|---|---|---|---|

Mean | 16.579 | 14.459 | 10.70 |

S.D | 6.081 | 5.903 | 8.186 |

A Kruskal–Wallis H test indicated that there were differences in three kinds of third-party players (χ2 (2) = 10.754, p = 0.005, effect size = 0.102). This post hoc analysis (pairwise comparisons) revealed that the actual average income of the punishers was higher than that of the helpers (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.054) and the PDN (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.004). In addition, the actual average income of the helpers was higher than that of the PDN (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, adjusted p = 0.054).

B3: Experiment 3

(1) The specific design of experiment 3

For Experiment 3, we applied two designs to minimize the effect of deception. First, although player 3 and player 5 did not exist, we still let player 4 wait for player 3 and player 5 to make decisions in turn. More importantly, to prevent player 4 from being skeptical about whether other players existed, in case they communicated with each other regarding their payoffs after the experiment, we set the payoff for player 4 according to the payoff result of player 3 in Experiment 2. In Experiment 2, the punishers received proposals that were less exploitive and had higher payoffs than the helpers and noncooperative players in the ultimatum game. If player 4, on average, regarded TPP as an effective deterrence signal, then players in that role who chose punishers as delegates should have expected that they would receive a higher payoff than other players. In addition, participants were thanked and debriefed. All participants may withdraw data provided prior to debriefing without penalty or loss of benefits to which they were otherwise entitled.

Experimental income settings:

The experimental income distribution of the fourth party that chooses different types of third parties in Experiment 3 was set based on the income of the three types of third parties in Experiment 2 (UG).

Income (RMB yuan) | Punisher | Helper | PDN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mean | (Std.err) | Mean | (Std.err) | Mean | (Std.err) | |

Experiment 2: third party (responder) | 16.579 | (1.433) | 14.459 | (0.984) | 10.7 | (1.169) |

Experiment 3 (known): fourth party | 16.724 | (1.145) | 14.118 | (1.5) | 10 | (4.183) |

Experiment 3 (unknown): fourth party | 17 | (2) | 14.259 | (1.154) | 10 | (2.224) |

Just as the different TPPG choices of the third party caused their incomes in the UG to vary significantly, the different choices of the fourth party also caused their incomes to vary significantly; for example, choosing a punisher made them more likely to have higher gains.

In Experiment 2:

There was a significant difference between the gains of the punishers, helpers and PDN (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ2 = 10.754, p = 0.005, effect size = 0.102).

In Experiment 3 (known group):

There was a significant difference between the gains of the punisher choosers, helper choosers and PDN choosers (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ2 = 7.186, p = 0.028, effect size = 0.144).

In Experiment 3 (unknown group):

There was a significant difference between the gains of the punisher choosers, helper choosers and PDN choosers (χ2 = 7.139, p = 0.028, effect size = 0.143).

(2) The bystanders chose delegates under different information conditions (known group vs. unknown group)

Fourth-party choice | Known group | Unknown group |

|---|---|---|

Punisher | 29 | 10 |

proportion | 56.90% | 19.60% |

95% CI | 42.79–70.93% | 8.33–30.89% |

Helper | 17 | 27 |

proportion | 33.30% | 52.90% |

95% CI | 19.94–46.72% | 38.76–67.12% |

Player who did nothing | 5 | 14 |

proportion | 9.80% | 27.50% |

95% CI | 1.36–18.25% | 14.77–40.13% |

(3) Fourth-party choices in multiple logistic regression

Fourth-party choice | Punisher | Player who did nothing | Helper |

|---|---|---|---|

Baseline category | Helper | Helper | Player who did nothing |

Known condition | 1.527*** | − 0.567 | 0.567 |

0.482 | 0.609 | 0.609 | |

Intercept | − 0.993 | − 0.657 | 0.657 |

0.372 | 0.331 | 0.331 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Luo, J., Niu, H. et al. When punishers might be loved: fourth-party choices and third-party punishment in a delegation game. Theory Decis 94, 423–465 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-022-09897-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-022-09897-6