Abstract

This article focuses on the applications of philosophical logic in the discipline of philosophy of religion of both ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ traditions, in which the problem of apparent ontological contradictions can be found. A number of philosophers have proposed using the work of those non-classical logicians who countenance the violation of the law of non-contradiction (LNC) to address this problem. I discuss (1) whether classical or non-classical account of logic is universal in applying to all true theories, and (2) whether there might be extra-logical considerations which affect what is the correct account of logic for the doctrines in question. With regard to Jc Beall’s application of non-classical (FDE) logic to the doctrine of the Incarnation, I argue using the evidence from the writings of church fathers that the meaning of negation found in the core claims of the doctrine of the Incarnation should not be interpreted in accordance with Beall’s FDE account, and that this extra-logical consideration refutes Beall’s project. Moreover, the FDE’s acceptance of the possibility of statements that are both true and false is contrary to what is allowed by the definition of negation in classical logic; therefore (contrary to Beall), Beall is in fact using a different definition of negation compared with the definition used by the classical account. I develop this point in interaction with contemporary philosophy of religion literature and explain its implications and significance for this discipline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, a number of philosophers have used non-classical logic to address the problem of apparent ontologicalFootnote 1 contradictions in the doctrinal systems of Eastern religions/philosophies and Christianity.

For example, the results of Graham Priest’s work on non-classical logic have been utilized by some scholars of Chan Buddhism and Taoism which postulate a transcendent realm with contradictory properties (Deguchi et al., 2021). The authors (which include Priest himself) argue that the contradictions should not be regarded as merely apparent, but true. They define dialetheism as the view that countenances the violation of the thesis that no contradiction can be true (p. 1), and state that the point of their book ‘is to show that many East Asian philosophers were indeed dialetheists; moreover, that dialetheism was central to their philosophical programs’ (p. 7).

On the Christian side, Jc Beall, (2021) has applied his own work on non-classical logic to the traditional Christian doctrine of the Incarnation in a book titled The Contradictory Christ: ‘The simple thesis of this book is that some claims are both true and false of Christ’ (p. 3). While most philosophers and theologians who have defended the traditional doctrine of the Incarnation have attempted to show that the contradictions between divine and human properties (e.g. being omniscient and being limited in knowledge) are merely apparent, Beall argues that these contradictions are true and that the correct account of logic does not rule them out.

Beall explains in the first two chapters of his book that first-degree entailment (FDE; a non-classical account of logical consequenceFootnote 2) does not rule out the possibility of gluts (sentences that are both true and false). He argues that FDE is universal in applying to all true theories (p. 9). Against classical logic assumptions, Beall offers theology-independent reasons to argue that a so-called subclassical account of logical consequence is the correct account:

Logic, on the ‘classical’ account, is exclusive: it recognizes no possibility in which an object falls into both the extension and antiextension of a predicate – no possibility in which a predicate is both true and false of an object…These constraints are overly strict from an alternative (viz., FDE) account of logic… the classical-logic constraints (above) are very, very well-motivated when one focuses one’s attention on a standard diet of examples from sciences like mathematics – the very diet to which the classical-logic account was historically directed. But reality is more than just mathematics. Reality appears to contain some surprising (however rare) phenomena that don’t naturally fit into the confines of classical-logic assumptions. Reflection on language’s strange phenomena (e.g., vagueness, paradoxical phenomena, and more) don’t obviously fall into the confines of (classical-logic-governed) mathematics (p. 31).

(I discuss the above reasons offered by Beall in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section and ‘Apparent Counterexamples to Classical Logic Assumptions’ section below).

Beall also highlights the distinction between logical consequence and extra-logical consequence. For example, he argues that FDE can accommodate those true theories in mathematics which (following classical logic) deny the possibility of gluts, because there are extra-logical consequences (due to theory/topic-specific considerations which affect the meaning of the terms) which can constrain the entailments of FDE resulting in the denial of the possibility of gluts in those theories (p. 55). Beall also claims in chapter 4 that extra-logical considerations in theology can be used to reply to various objections to the use of the FDE account for Christology. For example, he argues that, unlike logical consequence, theological consequence does not contrapose (p. 75).

The crucial debate concerns (1) whether the classical account or the non-classical account of logic is universal in applying to all true theories, and (2) whether there might be extra-logical considerations which affect what is the correct account of logic for the doctrines in question. The debate is relevant to Global Philosophy of Religion which studies different religious traditions around the world with different criteria for assessing different religious views; one needs to consider whether appealing to rational consistency begs the question against those traditions which do not regard the universality of rational consistency to be an important criterion. While disproving ontological contradictions might seem like a fairly intuitive task for many philosophers, there are other philosophers (e.g. Eastern religious philosophers, Priest, Beall) who do not share that intuition. Deguchi et al., (2021, p. 5) note that ‘Western philosophical traditions have generally been hostile to dialetheism. Again, generally speaking, the Asian philosophical traditions have been less so— though Western commentators on these traditions have been hesitant to endorse dialetheic interpretations of the texts involved for fear of making their favorite philosophers appear irrational.’ Against this, Deguchi et al. regard the endorsement of dialetheias to be a virtue of Eastern philosophy, stating that East Asian philosophers ‘may have developed important insights that evaded their Western colleagues as a consequence of this willingness to entertain, and sometimes even to embrace, paradox’ (p. 7). The implication is that a comparison with Eastern philosophy might contribute to or challenge traditional ways of thinking about the Christian faith.

I shall evaluate the above two issues in what follows. I shall begin with an assessment of Beall, (2021), followed by Deguchi et al., (2021). Grimm, 2005, pp. 49, 63) notes that there are different forms of the law of non-contradiction (LNC), dialetheism, negation, and contradiction (see also footnote 1). I shall argue that, with regard to the definition of contradiction (A and not-A), a non-classical logician and a classical logician are using the same word ‘not’ to mean different things: the former allows for gluts, but the latter does not. Different meanings of ‘not’ imply different meanings of the word ‘contradiction’. Thus (in actuality and despite Beall’s intentions and claims), a non-classical logician and a classical logician are using ‘contradiction’ to refer to different things. Hence, even though one says contradictions can exist and the other says contradictions cannot exist, both can be correct, because by ‘contradiction’ they mean different things. I shall also argue that, while the classical logician’s definition of negation implies that classical logic is universal in applying to all true theories (in the sense explained in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section), this does not imply that classical logic is adequate for all tasks, nor does it require the rejection of non-classical logic. On the contrary, one can argue that non-classical logics are helpful in situations in which (say) the definitions are vague (see the ‘Apparent Counterexamples to Classical Logic Assumptions’ section). In addition, I shall argue that there are extra-logical considerations which indicate that Beall’s FDE account is not the correct account of logic for the doctrine of the Incarnation. However, it might work for Eastern religious doctrines depending on their definition of negation, in which case they should be asked to clarify what they mean (e.g. by ‘not-effable’, see the ‘Concerning the Transcendental Realm in Some Eastern Religious/Philosophical Traditions’ section).

Concerning Beall’s Contradictory Christ

Some Differences Between the FDE Account and the Classical Account of Logic

Consider first the semantics for Beall’s FDE account (Beall, 2021, pp. 32–33):

An atomic sentence is at least true (false) iff the denoted subject is at least in the extension (at least in the antiextension) of the given predicate. Then truth and falsity conditions for molecular sentences are as follows…

-

Negations: ¬ A is at least true in model m iff A is at least false in model m.

-

Negations: ¬ A is at least false in model m iff A is at least true in model m.

Beall explains what he means by extension and anti-extension:

The extension of a predicate is the set containing all objects of which the predicate is true (i.e., all objects to which the true-of relation relates the predicate), and the antiextension the set of objects of which the predicate is false (i.e., all objects to which the false-of relation relates the predicate) …

-

An atomic sentence is true if and only if the denotation of the singular term (e.g., name) is in the extension of the predicate.

-

An atomic sentence is false if and only if the denotation of the singular term (e.g., name) is in the antiextension of the predicate (pp. 19–20).

In short, the FDE account defines truth and falsity conditions and negation in terms of extension and anti-extension, and in such a way that allows for some objects to fall into both the extension and anti-extension of a predicate.

One problem with Beall’s exposition of FDE in his book is that he defines falsity in terms of anti-extension and anti-extension in terms of falsity, which seems circular. Another problem is that Beall claims that both the classical and his non-classical (subclassical) account enjoy similar semantics. In particular, he claims that the meanings of the standard logical vocabulary of his FDE account (including that of logical negation) ‘enjoys exactly the same truth and falsity conditions for the logical vocabulary as the mainstream (viz., so-called classical) account. In this way, the meanings of logical vocabulary are what they’ve always been’ (Beall, 2021, p. 11). However, Beall fails to note that his FDE account’s acceptance of the possibility of statements that are both true and false is contrary to what is allowed by the meaning of negation in the classical account. To elaborate, the FDE account is different from the classical account of logic which ‘recognizes no possibility in which an object falls into both the extension and antiextension of a predicate – no possibility in which a predicate is both true and false of an object’ (Beall, 2021, p. 31). The classical account follows from a particular meaning and definition of ‘not’. This is illustrated by Huemer’s, (2018) statement that ‘if you think there is a situation in which both A and ~ A hold, then you’re confused, because it is just part of the meaning of “not” that not-A fails in any case where A holdsFootnote 3…Now, a contradiction is a statement of the form (A & ~ A). So, by definition, any contradiction is false’ (p. 20; italics mine).Footnote 4

Understood in this way, there cannot be any exception to the classical account of logic. For example, there cannot be a shapeless square because ‘shapeless’ (no-shape) would fail in any case where there is a shape (e.g. a square), i.e. there is no possibility in which an object falls into both the extension and anti-extension of a predicate ‘shapeless’. This illustrates that the word ‘fail’ in Huemer’s statement is understood in accordance with Beall’s characterization of the classical account of logic, i.e. in terms of ‘no possibility in which an object falls into both the extension and anti-extension of a predicate’.

It might be objected that FDE entertains four truth values: true (T), false (F), both true and false (B, the truth value glut), and neither true nor false (N, the truth value gap), and that one can obtain standard classical propositional logic from FDE by requiring that no statement is assigned either B or N. However, this does not deny my point that FDE’s acceptance of the possibility of statements that are both true and false (B, the truth value glut) is contrary to what is allowed by the meaning of ‘not’ in the classical account. Therefore, in this sense, Beall is (inadvertently) using the word ‘not’ to mean something different compared to the use of the word ‘not’ in the classical account. This point is observed by logician Greg Restall’s review of Beall’s work, in which he states that ‘our everyday understanding of the meaning of “not” is that each claim excludes its negation – there is no possibility in which a sentence and its negation are both true. Paraconsistent logics are revisionary accounts of how we should understand negation…we shouldn’t deny that it is a revisionary account of the meaning of logical vocabulary’ (Restall, 2022, p. 3; italics mine).

The Meaning of Negation in Christological Statements and Extra-logical Considerations

Let us now consider Beall’s application of his FDE account to Christology, as illustrated by his discussion of ‘Christ is mutable and immutable’ (Beall, 2021, p. 100). Beall rejects various proposed solutions to this and other apparent contradictions in Christology,Footnote 5 such as arguing that Christ is mutable in one sense and immutable in another, or arguing that Christ is mutable in one respect (i.e. his human nature) and immutable in another respect (his divine nature), and chooses to affirm a true contradiction instead (p. 124). Now, Beall himself writes, ‘I am not hereby proposing that theologians should seek to find contradictions willy nilly. The reason that we generally reject all logical contradictions is that true ones are ultimately few and far between’ (Beall, 2021, p. 7). Thus, in order to justify the acceptance of a true contradiction in this case concerning Christological statements, Beall would appeal to extra-logical considerations in theology, similar to the way he claims that extra-logical considerations in theology allows him to argue that, unlike logical consequence, theological consequence does not contrapose (Beall, 2021, p. 75).

There are two problems with Beall’s application of FDE to Christology.

The first is the difficulty with spelling out the meanings of Christological claims. For example, what does not-mutable mean when it is mutable in the same respect? Does not the basis for thinking that Christ is not-mutable rule out the claim that he is mutable? Since the Christian wants to make meaningful statements by affirming, as the Christian tradition does, that Christ is not-mutable and mutable, he/she should explain what is meant by these statements; it is not enough to claim that it is a ‘mystery’ or a ‘truth value glut’ and leave it at that. In relation to this point, Islamic apologists have long complained that many Christians use terms that carry no meaning when they explain their beliefs concerning the Incarnation (Thomas, 2002, p. 231).

The second problem with Beall’s contradictory Christology is that, in the discipline of theology, the extra-logical considerations would include the interpretation of the relevant Christological statements in Scripture and tradition. Now, to interpret these writings properly, their historical background has to be taken into consideration. However, as Beall inadvertentlyFootnote 6 admits on page 151, ‘no theologian or theologically inclined philosopher has advocated a specific contradictory theology.’ Beall is a logician who is familiar with the history of logic. Likewise, the eminent historical theologian Sarah Coakley, (2002, p. 155) who is familiar with the history of theology observes that ‘the overwhelming impression from following the debate leading up to Chalcedon… as well as that which succeeds it, is that… “paradox” [in the sense of being self-contradictory or incoherent] is vigorously warded off’. While there are different senses of ‘contradiction’ and ‘coherence’, in context, Coakley’s observation is specifically concerned with contradictions akin to gluts which Beall embraced for Christology. To illustrate Coakley’s observation, consider the following statements from the writings of the church fathers Pope Leo and Cyril of Alexandria which were the foundational documents of the Chalcedonian orthodoxy (Price, 2005, p. 65) that Beall, (2021, p. 3) seeks to defend:

‘For the payment of the debt owed by our nature divine nature was united to the passible nature, so that – this fitting our cure – one and the same, being the mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, would be able to die in respect of the one and would not be able to expire in respect of the other’—Tome of Leo (italics mine).

‘Since again his own body by the grace of God tasted death on behalf of everyone, as the apostle says, he himself is said to have suffered death on our behalf, not as though he entered into the experience of death in regard to his own nature (for to say or think that would be lunacy) but because, as I have just said, his own flesh tasted death’—Cyril, Second Letter to Nestorius (italics mine).

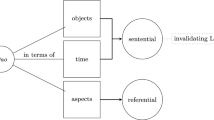

The above statements from Leo and Cyril indicate that they warded off a contradiction by attributing A and not-A to different aspects of Christ (e.g. ‘would be able to die’ to human body/flesh; ‘not be able to expire’ to divine nature). As Beall himself (inadvertently) notes, the church fathers were on the quest to consistentize Christ and rejected the logical possibility of Christ’s being a contradictory being (Beall, 2021, p. 110). This indicates that the Chalcedonian fathers did not interpret the negations (e.g. ‘not be able to expire’) found in the Christological statements in accordance with Beall’s FDE account which allows for the logical possibility of Christ’s being a contradictory being.

Beall might object by claiming that using a different definition of ‘not’ may deliver insights (even if it is revisionary), and by suggesting that perhaps the church fathers would have endorsed FDE if someone had presented it to them. As it stands, there is no indication that they endorsed FDE, but Beall, (2021, p. 109) replies by saying he finds it difficult to believe that Christians are ‘required to be in step with all theories held by conciliar fathers… beyond core claims of Christ and God more generally’.

In reply, it should be noted that the original intent of Beall’s work is not merely to deliver insights but to rebut the objection against the traditional Christian doctrine of the Incarnation, i.e. ‘the fundamental problem of Christology’ (Beall, 2021, p. 3), and this article focuses on whether Beall has successfully accomplished the latter task. To answer this question, one needs to distinguish between (1) the core claims of the traditional doctrine of the Incarnation and (2) the theories that attempt to address the problems with those core claims. While I agree that Christians are not required to be in step with all theories held by conciliar fathers, the writings of Leo and Cyril cited above indicate that the core claims have traditionally been understood as involving the meaning of negations (e.g. ‘not be able to expire’) that do not accord with Beall’s FDE account, because the meaning of ‘not’ has traditionally been understood to be such that ‘each claim excludes its negation’ (to use the phrase in Restall, 2022, p. 3). I have also argued above that the meaning of negation in the Biblical authors and church fathers is different from the meaning of negation in Beall’s FDE account. Given this, the endorsement of FDE for Christology would entail a distortion of the original meaning of the core claims of the traditional doctrine of the Incarnation, and would end up talking about something else other than what the traditional doctrine of the Incarnation originally refers to. (It is also interesting to note that Beall (2021, p. 4) dismisses kenotic Christology because it goes against traditional Christology. In that case, Beall should also be unwilling to consider a contradictory Christ because it goes against tradition).

The conclusion that the extra-logical considerations count against Beall’s view implies that, even if Beall’s FDE account is universal in applying to all true theories, the extra-logical considerations would constrain the entailments of FDE resulting in the denial of the possibility of gluts in Christology.Footnote 7 That is, in a way similar to how (on Beall’s view) the extra-logical considerations constrain the entailments of FDE resulting in the denial of the possibility of gluts in true theories in mathematics.

In summary, the problem with Beall’s view is that, in order to embrace a true contradiction for Christology, Beall would need to use a definition of negation which (unlike the definition of the classical account) allows for the possibility of gluts. However, such a definition would convey a meaning which is different from what the Biblical authors and church fathers who did not have a ‘glut-theology’ framework of understanding would have understood by negation. Beall’s usage of his definition of ‘not’ for statements relevant to the Incarnation would require interpreting the Scripture and tradition in a very different way from the original meaning of the texts, and thus (contrary to Beall’s original intention) would be guilty of bad hermeneutics and of talking about something else.

For an example of talking about something else: using different definition of negation, one can also say that there are shapeless (no-shape) squares if one defines ‘no’ in such a way that no-shape does not fail in the case where there is a shape (e.g. a square), in which case the term ‘no-shape’ loses its original meaning as stated in the ‘Some Differences Between the FDE Account and the Classical Account of Logic’ section and one is talking about something else already.

It is illegitimate to try to solve a problem or rebut an argument by talking about something else. To do that would be like someone objecting to ‘All humans are mortal, Socrates is a human, therefore, Socrates is mortal’ by using alternative definitions of human or Socrates, which of course misses the point of the argument by talking about something else. Likewise, to rebut the argument against the Incarnation (‘the fundamental problem of Christology’ as Beall [2021, p. 3] notes) by using the word ‘not’ to mean something different from that understood by the Biblical authors, church fathers, and their opponents would be to miss the point of the argument by talking about something else. It would also be contrary to Beall’s commitment to ‘no new meanings, no playing with words’ (p. 3). The difference between the meaning of ‘not’ in the traditional Christological statements and the way Beall understands it is that the former would not allow for gluts, whereas the ‘not’ in Beall’s FDE account allows for gluts. Given Beall’s commitment, for the purposes of Christology, he should follow the meaning of ‘not’ as understood by the Biblical authors and church fathers, i.e. the no-glut account, and if so, his contradictory Christology should be rejected.

The problem explained above outweighs whatever advantages Beall claims in favour of his contradictory Christology in chapters three and five of his book. For example, Beall claims that his proposal has the advantage of simplicity. However, as explained previously, given the no-glut account of the meaning of ‘not’, any proposal which affirms a contradiction cannot be true (even if it is simpler). Thus, simplicity cannot help his view since his view affirms a contradiction.

The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction

The ‘shapeless square’ example explained above in (‘for example, using different definition of “not/no”, one can also say that there are shapeless [no-shape] squares…’) illustrates a more general point about how the meaning of ‘no/not’ is understood in classical logic concerning contradiction (‘A and not-A’). If Beall wants to claim that there are violations of classical logicFootnote 8 by using the word ‘no/not’ to mean something different, this would entail an alternative meaning of ‘contradiction’ and render his claim invalid. That is, he would no longer be talking about violations of classical logic because he would be talking about something else.Footnote 9 The definition of contradiction remains the same (A and not-A), but a different meaning of ‘not’ would entail a different meaning of ‘contradiction’, and likewise a different topic.

Beall might object that citing the definition of ‘not’ as explained in Huemer’s account begs the question against his non-classical account. As Priest argues, there are different definitions of ‘not’ and different theories of negation and denial, suitable for different purposes (Priest, 2006, pp. 76–77, 104). ‘To assume beforehand that the classical account of negation is the correct one, in the sense that it captures how negation works in the vernacular, again begs the question against the dialetheist…it is circular just to assume that classical negation gets it right’ (Priest et al., 2022).

In response, I would like to clarify that I do agree with Priest that there are different definitions of ‘not’ suitable for different purposes. Using the example of ‘shapeless square’, I have illustrated the definition of ‘no/not’ for the purposes of discussing whether there can be any ontologicalFootnote 10 contradiction (‘A and not-A’) that violates classical logic. The meaning of ‘no/not’ which I convey using the example is clear: shapeless = no shape, which fails in any case where there is a shape (such as a square). This illustrates the meaning of ‘not’ which I intend to convey is that ‘not-A fails in any case where A holds’ (Huemer, 2018, p. 20), which implies there cannot be any contradiction, and that is what I mean by saying that the classical account is correct. If a dialetheist thinks that there could be shapeless squares, then he/she would be using the words shapeless/square with different meanings, i.e. he/she would be talking about something else. Likewise, if a dialetheist were to use a different definition of ‘not’ so as to argue that there are violations of LNC, he/she would be talking about something else rather than the violation of classical logic per se, and to miss the point that there cannot be any violation of LNC (understood in a certain sense). Grimm, 2005, p. 61) notes that ‘by the LNC’s proponents’ lights it thus appears that the Dialetheist fails even to engage the real principle at issue because he is constantly reading it as something weaker, constantly re-reading their “not” as something other than the intended “not”, or their “false” as something other than the sense of “false” intended’.

To illustrate the abovementioned point, consider the following analogy: the word ‘bachelor’ can mean different things. X explains to Y what she means by ‘bachelor’ by referring to an unmarried male, and explains that it follows from this definition of bachelor that there cannot be a married bachelor. Y says that there can be a married bachelor, by which she means someone who holds a first degree from a university. Both X and Y are correct, because they are using ‘bachelor’ to refer to different things. If one of them says that the other is wrong, she would be missing the point. It would be wrong for one to accuse the other of begging the question, because it is not the case that they are referring to the same thing and one is simply assuming that her conclusion is correct and the other is wrong. Rather, they are referring to different things: one is referring to an unmarried male while the other is referring to someone who holds a first degree from a university, and each one has explained what she means by ‘bachelor’ and how her conclusion follows from the meaning of the terms. Likewise, I have explained how the inviolability of LNC follows from a particular definition of ‘not’, just like ‘there cannot be a married bachelor’ follows from a particular definition of ‘bachelor’. This does not deny that there are other legitimate definitions of the word ‘bachelor’, just as there are other definitions of ‘not’ which Beall and Priest use.

One might object to my argument by claiming that, just as Einstein corrected Newton’s view of gravity without talking about something else, likewise the non-classicists are saying that the classicists are wrong about contradictions without talking about something else.

In reply, this is a false analogy because both Einstein and Newton were referring to the same phenomenon of things gravitating towards one another, i.e. they were referring to the same subject but Einstein described its behaviour more accurately. By contrast, Beall and Huemer are in actuality referring to different things when they use the term ‘contradiction’, because (as I have explained above) they use different definitions of the key term ‘not’ which stands at the core of the definition of contradiction (‘A and not-A’). Thus, if non-classical logicians claim that classical logicians are wrong about contradictions (or vice versa), then they are wrong about that. However, the non-classicist’s theory does not have to be committed to that claim. Rather, the theory can affirm that both classical logic and non-classical logic are correct by clarifying that they are actually referring to different things when they use the term ‘contradiction’ (see also the different senses of ‘contradiction’ explained in footnote 1, and the pragmatic usefulness of non-classical logic in the ‘Apparent Counterexamples to Classical Logic Assumptions’ section).

Beall might object that, when we consider Christ, we need to use a different understanding of the meanings of our concepts (including those of classical logic), because we are not dealing with an ordinary (finite) being.

There are two problems with the above objection.

First, Beall is referring to the Christ in Christian tradition, but as I have argued in the ‘The Meaning of Negation in Christological Statements and Extra-logical Considerations’ section, the extra-logical considerations (i.e. the Christian tradition) count against the use of an alternative account of logic in place of classical logic in that particular case.

Second, the suggestion that we use a different understanding of the meanings of our concepts (including those of classical logic) still presupposes the validity of classical logic, because to ‘use a different understanding of the meaning of…classical logic’ means to use ‘not-classical logic’ where ‘not’ is used in an exclusive sense so as to claim that classical logic fails. However, this exclusive sense is the sense which the classical account is using for the LNC. In other words, to deny the validity of the LNC, one still has to presuppose the validity of the LNC. This indicates that the LNC cannot in fact be violated.

In summary, with regard to the question ‘why think that classical logicians are correct about the inviolability of the LNC’, the answer is that we know what they mean by ‘not’, and we know that inviolability of the LNC (understood in a certain sense) follows from their definition of ‘not’. That is what it means to say that classical logicians are correct about the inviolability of the LNC, just as it is correct to say that there cannot be ‘married bachelors’ where the term ‘bachelor’ is understood in a certain sense. This does not deny the possibility that the non-classical account can also be correctFootnote 11 if it uses a different definition of ‘not’. Rather, the argument here is that the word ‘not’ can have different meanings (just like the word ‘bachelor’ can have different meanings), and if it is defined in accordance with Beall’s FDE account then contradictions are possible, but that does not deny the fact that if it is defined in accordance with Huemer’s statement then contradictions are impossible. There cannot be any violation of the LNC understood in the latter sense. In other words, the LNC (understood in this sense) is necessarily true. It would hold even at levels far beyond our daily experiences, such as ‘the transcendent realm’ (if there is one), because there cannot be something like a shapeless square at those levels too (see further, the ‘Concerning the Transcendental Realm in Some Eastern Religious/Philosophical Traditions’ section below). The necessity of the LNC indicates that it is not merely a psychological principle of reasoning nor a concept in the mind. Rather, it is descriptive of reality, as illustrated by the impossibility of shapeless square in reality. While the LNC uses terms (e.g. ‘not’) that are defined by human communities, the LNC itself is not based on agreed definition by human communities, as illustrated by the fact that, if some other communities use a different definition, they would be talking about something else, but not refuting the LNC per se, which remains necessarily true.

Concerning the Transcendental Realm in Some Eastern Religious/Philosophical Traditions

The point which I have explained above in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section also applies to Eastern religious/philosophical traditions. Deguchi et al., (2021) argue that, while interpretation is always a difficult and contentious matter, ‘in some cases, that the view being endorsed is dialetheic is virtually impossible to gainsay. Moreover, bearing in mind the historical and intellectual influences that run between our texts, the central claim of our book, that there is a strong vein of dialetheism running through East Asian philosophy, would seem to be as definitively established as any piece of hermeneutics can be’ (p. 7). In support of their interpretation, they state that various early Hindu and Buddhist philosophersFootnote 12 endorse a framework called ‘the catuskoti (four corners), according to which a statement may be true (only), false (only), both, or neither’ (ibid, p. 6), and that many Chinese Buddhist commentators and Daoist philosophers embraced contradictions and explored their consequences (pp. 7, 91). Deguchi et al. consider a number of texts from East Asian philosophy, such as the influential Chinese philosophical text the Daodejing (traditionally attributed to Laozi), with its famous opening lines stating that ‘The Dao that can be described in language is not the constant Dao; the name that can be given it is not the constant name’. (p. 15). They note the commentary of the important Neo-Daoist commentator Wang Bi (226–249 CE) who glosses it as affirming that the Dao is ineffable, which generates a contradiction since the text talks about it by asserting that it is ineffable, i.e. the Dao has the properties of being effable and ineffable (pp. 143–144). Deguchi et al. examine various possible explanations for why neither the text nor the commentary tries to explain away the contradiction, and they conclude that ‘the most obvious and compelling reading is simply that the author of the Laozi and Wang Bi accepted the contradiction’ (pp. 20–21).

Thus, according to Deguchi et al., certain Eastern religious/philosophical traditions (e.g. Daoism) postulate a transcendent realm (e.g. of the Dao) with contradictory properties, and Deguchi et al. claim that the LNC can be violated (pp. 1–7). However, the latter is impossible, because (as explained in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section) there cannot be something like a shapeless square (understood in accordance with the definition of ‘not’ in the classical account) in the transcendent realm either.Footnote 13 This conclusion is not based on our inability to imagine it but based on understanding ‘it is just part of the meaning of “not” that not-A fails in any case where A holds’ (Huemer, 2018, p. 20). Thus, the not-effable (ineffable) Dao would fail in any case where there is an effable Dao.

Deguchi et al. might reply by appealing to extra-logical considerations in Eastern traditions to justify using a different definition of ‘no/not’ in their doctrinal systems.

In response, aside from the difficulty of spelling out the meaning (e.g. what does ‘no’ attribute mean in that case?), the problem is that, by using a different definition of ‘no/not’, they would no longer be talking about the violation of LNC per se (this point has been explained earlier in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section), contrary to what they claim in Deguchi et al., (2021, pp. 1–7).

Apparent Counterexamples to Classical Logic Assumptions

Both Deguchi et al., (2021, p. 3) and Beall, (2021, p. 8) mention the liar paradox (is the sentence ‘This sentence is false’ true or false?) as a well-known entity that ‘apparently instantiate or exemplify or have both of the given contrary properties’ (Beall, 2021, p. 8).

However, both of them fail to note that the claim that contradictions can exist in self-referential paradox in linguistic games (which may be due to inadequacies of language) is irrelevant to the claim that ontological contradictions can exist in a concrete individual (the Incarnate Christ) or the transcendent realm. Moreover, Huemer, (2018, p. 29) has argued that one can resolve the liar paradox by showing that the liar sentence fails to express a proposition because the rules for interpreting the sentence are inconsistent; thus, it does not have the property of truth or falsehood; hence, there is (in fact) no glut and no contradiction.

While Huemer gives no model to serve as proof of consistency, this does not invalidate his argument which is simply intended to show that his ‘solution to the liar paradox holds that the liar sentence fails to express a proposition due to an inconsistency built into our language’ (p. 29). Priest et al., (2022) mention the ‘strengthened’ liar paradox such as L: L is not true, and argue that, if this sentence is neither true nor false, it is not true; but this is precisely what it claims to be; therefore, it is true. Huemer, (2018, pp. 34–36) replies to the ‘strengthened’ liar paradox by denying that L makes any claim at all. L does not make any claim because it fails to express a proposition. However, one can say that N: L is not true. Huemer explains ‘N expresses the proposition that L is not true; yet L does not express that proposition, even though L is syntactically identical to N. Why is this? Because when we read L, we are invited to accept an inconsistent story about the proposition that it expresses; but when we read N, there is no inconsistent story about what N expresses’ [p. 35]). Huemer also replies to other paradoxes in his book (Huemer, 2018). For example, Huemer argues that Russell’s paradox does not imply the denial of LNC; he explains that the solution to the paradox (which defines ‘the Russell set’ as the set of all things that are not members of themselves) is to argue that the Russell set does not exist given that it has an inconsistent definition (pp. 42–43).

While multiple non-classical logics have been developed in recent years, their proven utility has to do with definition, designation, proving, computability problem solving, etc.; i.e. they are helpful in situations where (say) the definitions are vague. (This does not imply it should be applied to Christology [as Beall argues], because as explained in the ‘The Meaning of Negation in Christological Statements and Extra-logical Considerations’ section, the extra-logical considerations count against such an application.) On the other hand, as I have argued in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section, classical logic applies to what is actually the case or can be the caseFootnote 14 (regardless of whether one can define it, prove it, etc.). Thus, for example, it cannot be the case that shapeless squares exist.

Some Eastern religious mystics have appealed to the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics and claimed that it violates the LNC (Capra, 2010). However, the Copenhagen interpretation is unproven. Other viable interpretations exist, and some of them, such as de Broglie-Bohm’s pilot-wave model and Everett’s Many Worlds Interpretation, are perfectly deterministic and consistent with the laws of logic. Compare with other viable interpretations, the Copenhagen interpretation is a bad interpretation because (as explained in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section) the LNC cannot be violated.

Conclusion

I have shown that there cannot be any ontological contradictions that violate the LNC (understood in a certain sense, following a particular definition of negation), just as there cannot be any married bachelor (following a particular definition of ‘bachelor’ as an unmarried male). This conclusion is compatible with the claim that there are viable non-classical accounts of logic which are helpful for various tasks, since those non-classical accounts use different definitions of negation and hence do not violate the LNC (understood in the sense I have defined). Whether those accounts are applicable to a particular situation would depend on extra-logical considerations; I have shown in the ‘The Meaning of Negation in Christological Statements and Extra-logical Considerations’ section that there are extra-logical considerations which indicate that Beall’s FDE account is not the correct account of logic for the traditional doctrine of the Incarnation which he seeks to defend. In particular, I have argued that Beall’s inadvertent admission (on page 151 of his book) and textual evidence from the church fathers (such as Pope Leo and Cyril) indicate that the meaning of negation found in the core claims of the traditional doctrine of the Incarnation should not be interpreted in accordance with Beall’s FDE account. Moreover, the FDE’s acceptance of the possibility of statements that are both true and false is contrary to what is allowed by the definition of ‘not’ in classical logic; therefore, Beall is in fact using a different definition of negation compared with the definition used by the classical account.

An objector might ask ‘why think that the classical account’s definition of negation is the best? On the other hand, if the different definitions are equally good, why not understand the LNC in terms of a contradiction-permitting sense of negation?’.

In response, I would like to clarify that I do not claim that the classical account’s definition of negation is the best simpliciter. There is no ‘best’ definition of negation because (as noted in the ‘The Meaning of Negation and the Law of Non-contradiction’ section) different negations are suited for different purposes. (This claim is related to the debate concerning logical pluralism, which holds that more than one logic can be correct. In particular, the telic version of domain-neutral logical pluralism claims that there is at least one telos or goal that a logic must meet in order to be correct, and that more than one logic meets that goal or goals ‘either because there is a single telos and more than one logic meets it, or because there is more than one goal that multiple logics meet’ Russell & Blake-Turner, 2023.) Nevertheless, for the purpose of stating the Law of Non-Contradiction, a contradiction-permitting sense of negation is inappropriate on my view, since that would be contrary to the purpose of stating the Law as a law in the first place, which is to express the sense in which there cannot be contradictions. If the Law is permissive, it would no longer be a ‘law’ in the intended sense.

An objector might claim that any proposal that involves making the LNC a consequence of a specified definition would entail that the LNC cannot be in any way a contentious claim that people could or do challenge; thus, the conclusion of this article is insignificant.

In reply, while I have argued that Beall’s FDE does not (in actuality) challenge the LNC (since FDE uses a different definition of negation), the problem is that Beall himself claims the possibility of gluts which violate the LNC (see footnote 8). The conclusion of this article is significant, because:

-

(1)

It indicates that Beall, (2021) and others (e.g. Deguchi et al., 2021) who claim that the LNC can be violated have failed to distinguish between different forms of the LNC and have failed to state clearly that a particular form of the LNC cannot be violated, but have instead been talking about something else other than that particular form of the LNC. Moreover,

-

(2)

That particular form of the LNC (understood as a consequence of a specified definition) is significant, because it conveys the sense in which statements such as (say) ‘it cannot be the case that the universe exists and not-exists’ and ‘there cannot be a cause of an uncaused First Cause’ are to be understood, and which indicates that such statements cannot be violated.

-

(3)

The strict sense of LNC (as well as the non-permissive definition of negation on which it is based) is important for various types of inferences, such as the deduction used in the Cosmological Argument, as illustrated by the examples of statements in (2) above. The mentioning of the Cosmological Argument is particularly relevant to the discussion here because, if the argument is sound (i.e. if the premises are true and the deduction is valid), this would have implications for the transcendent realm which Deguchi et al. are concerned about (see Loke, 2022).

-

(4)

The inviolability of such a form of the LNC rightly challenges those Eastern religious philosophers who claim that there are true contradictions to clarify what they mean by their ‘contradictory’ terms, and to explain the meaning in a way that would not violate this form of the LNC. It also rightly challenges Christian theologians to think of coherent models for the Incarnation (see, for example, Loke, 2014). It is one thing to claim that there is a transcendent realm which is ‘supra-rational’ in the sense that it exceeds the capacity of human reason to comprehend (Avis, 2021, p. 181), it is another thing to claim that it might have contradictory properties. Religious scholars might try to explore various other ways to address the problem of apparent ontological contradictions in their doctrinal systems, but any proposal which violates this form of the LNC should be rejected.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Unless otherwise stated, in this paper ‘contradiction’ refers to ‘ontological contradiction’. Grim (2005) estimates that there are ‘some 240 senses of contradiction’ (p. 55). He arrives at his estimate by noting at least four basic forms of approaches to contradiction ‘semantic, syntactic, pragmatic and ontological—multiplied by (1) a distinction between implicit and explicit contradictions, multiplied by (2) contradictions as pairs or single statements, multiplied by (3) the number of distinctions between token sentences, types, statements, propositions, assertions and claims, with that in turn multiplied by (4) the number of senses of negation’ (p. 55). Grim explains that ontological contradiction is distinct from other senses of contradiction as follows: on the ontological approach to contradictions, ‘a contradiction would be…a state of affairs. A contradictory state of affairs would be one in which something had a particular property and also an incompatible property, or in which something both had a particular property and lacked that property’ (p. 53). As explained in the ‘Concerning Beall’s Contradictory Christ’ and ‘Concerning the Transcendental Realm in Some Eastern Religious/Philosophical Traditions’ sections, the religious doctrines in question intend to refer to ‘state of affairs’ such as ‘transcendent realm’ or ‘Incarnation’; thus, the ontological approach will be the focus of this essay.

p is a logical consequence of X if and only if there is no possibility in which everything in X is true but p is untrue (Beall, 2021, p. 26).

Huemer’s view that ‘not-A fails in any case where A holds’ fits Beall’s characterization of the classical account of logic which ‘recognizes no possibility in which an object falls into both the extension and antiextension of a predicate – no possibility in which a predicate is both true and false of an object’ (Beall 2021, p. 31). Beall distinguishes this view from Beall’s own FDE account which allows for the possibility of an object falling into both the extension and anti-extension of a predicate (pp. 32–33).

The statement from Huemer which I cited (taken by itself) does not imply nor exclude the law of explosion (also known as ex contradictione quodlibet [ECQ]): A ∧ ∼A → B (where B is an arbitrary consequent). By contrast, Boolean negation implies ECQ, while De Morgan negation excludes ECQ. Huemer (2018, p. 22 n.6) states that Priest and Beall ‘frame the issue in terms of whether the negation operator validates explosion (the principle that (A & ~ A) entails B, for any arbitrary B). My claim is not that the meaning of negation by definition validates explosion. My claim is that the meaning of negation directly rules out a sentence and its negation both being true’.

Eric Yang, (2021) argues in his review that Beall’s rejection is based on inadequate reasons.

Beall’s point on page 151 is to emphasize the uniqueness of his contribution to theological discussion rather than to discuss the historical background for the interpretation of the relevant Christological statements in Scripture and tradition. However, as I explain in the text, his point has implication for the latter.

It would also result in the denial of the possibility of gluts for the doctrine of the Trinity, contrary to Beall, (2021, chapter 6).

Beall, (2021, p. 31): ‘Reality appears to contain some surprising (however rare) phenomena that don’t naturally fit into the confines of classical-logic assumptions’; in the rest of his book, Beall argues that the Incarnation does not fit these assumptions.

Cf. Quine who famously argues that ‘here, evidently, is the deviant logician’s predicament: when he tries to deny the doctrine he only changes the subject’ (Quine, 1970, p. 81). I avoid the phrase ‘change the subject’ because the word ‘change’ might give the impression of begging the question by presupposing that the classical logicians got the original subject correct or that ordinary language always uses the classical concept of negation. The phrase ‘talking about something else’ does not have such an implication, but rather highlight the fact that, by using different definitions of negation, the classical logician and non-classical logician are in fact talking about different things. I explain below that, in context, to raise an objection by ‘talking about something else’ does not concern ‘mere verbal disputes or generally metalinguistic’ (Beall, 2019, p. 203n1), but rather is guilty of missing the point of the argument.

See footnote 1.

Although, even if it is a correct account, it should not be used to affirm the possibility of gluts in the case of the doctrine of the Incarnation, because the extra-logical consideration in that case forbids it, see the ‘The Meaning of Negation in Christological Statements and Extra-logical Considerations’ section.

Deguchi et al. note that later Indian philosophy is much less dialetheism-friendly.

A transcendent realm would adhere to the law of non-contradiction but not necessarily adhere to laws of nature, and therefore can be ‘transcendent’ in that sense (and perhaps in other senses).

See footnote 1.

References

Avis, Paul. (2021). Revelation, epistemology, and authority. In The Oxford handbook of divine revelation ed. Balázs Mezei, Francesca Aran Murphy, and Kenneth Oakes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beall, Jc. (2019). On Williamson’s new Quinean argument against nonclassical logic. Australasian Journal of Logic, 16, 202–230.

Beall, Jc. (2021). The contradictory Christ. Oxford University Press.

Capra, Fritjof. (2010). The Tao of physics: An exploration of the parallels between modern physics and eastern mysticism. Massachusetts: Shambhala.

Coakley, S. (2002). What Chalcedon solved and didn’t solve. In S. T. Davis, S. Daniel Kendall, & S. Gerald O’Collins (Eds.), The Incarnation (pp. 143–163). Oxford University Press.

Deguchi, Y., Garfield, J., Priest, G., & Sharf, R. (2021). What can’t be said: Paradox and contradiction in East Asian thought. Oxford University Press.

Grimm, Patrick. (2005). What is a contradiction? In G. Priest, Jc Beall, and B. Armour-Garb (eds.), The law of non-contradiction: New philosophical essays, 49–72. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huemer, M. (2018). Paradox lost. Springer.

Loke, A. (2014). A Kryptic model of the Incarnation. Routledge.

Loke, A. (2022). The Teleological and Kalam Cosmological Arguments revisited. Springer.

Price, R. (2005). The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon. Liverpool University Press.

Priest, G. (2006). Doubt truth to be a liar. Oxford University Press.

Priest, Graham, Francesco Berto, and Zach Weber. (2022). Dialetheism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/dialetheism/

Quine, W. V. O. (1970). Philosophy of logic. Prentice Hall.

Restall, Greg. (2022). Jc Beall, The contradictory Christ. Religious Studies, 1–4.

Russell, Gillian and Christopher Blake-Turner. (2023). Logical pluralism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition). Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/logical-pluralism/

Thomas, D. (Ed.). (2002). Early Muslim polemic against Christianity: Abu ‘Isa al-Warraq’s ‘Against the Incarnation.’ Cambridge University Press.

Yang, Eric. (2021). Review of Jc Beall’s the contradictory Christ. Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. https://ndpr.nd.edu/reviews/the-contradictory-christ/

Funding

Open access funding provided by Hong Kong Baptist University Library. Hong Kong Research Grants Council General Research Fund Project number 18606721. September 2021 to August 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loke, A.T.E. The Law of Non-contradiction and Global Philosophy of Religion. SOPHIA (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11841-024-01001-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11841-024-01001-5