Abstract

We examine whether anti-corruption intensity strengthens tax enforcement effectiveness in China. Using hand-collected anti-corruption data and aggregate tax enforcement data, which include the probability of tax audits and tax deficiencies, for a sample of 11,687 firm-year observations from 2012 to 2017, we find that anti-corruption intensity increases the deterrence role and the enforcement role of tax audits. We also identify the fear effect as a possible channel through which anti-corruption intensity affects tax enforcement effectiveness. Overall, the results indicate that anti-corruption intensity can improve a revenue agency’s effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data is available upon request.

Notes

According to our conversations with some officials, their benefits dropped significantly following implementation of the campaign.

“Princeling” is a term first coined by the media, referring to the offspring of the top politicians. See Page (2011).

The evaluation by local government is also important for tax agents of the SAT.

It is the finance bureau through which local government affects the local tax bureau. A change in local government leadership may have effects on tax enforcement. For example, after the Bo Xilai scandal was exposed, he was removed from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 2012, and the Chongqing government immediately ordered its Bureau of Finance to enhance tax enforcement (21st Century Business Herald, 2013).

Slemrod et al. (2001) conjecture that individual taxpayers claimed more tax benefits to create a more aggressive starting point for negotiations with the tax authority, with the goal of minimizing their tax liability, given that they knew the returns they were about to file would be “closely examined.”.

Chinese officials have different administrative levels. The ranks from the lowest to the highest are as follows: fuke, zhengke, fuchu, zhengchu, futing, zhengting, fubu, zhengbu, fuguo and zhengguo. Futing is approximately the same level as mayor, and can make some major decisions in a province/region.

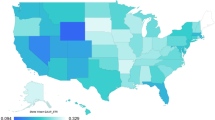

We focus only on investigated persons at the regional level, rather than the central level. This allows us to test whether local tax enforcement effectiveness changes due to local officials being investigated. We also use the number of investigated officials in a region divided by the total population in that region as the measure of anti-corruption intensity. The results are exactly the same. In addition, the investigated individuals in corruption investigations in China have been found guilty.

Unlike Lin et al. (2018), we focus only on audit probability and audit outcome and not on audit expertise. This is because we test the impact of anti-corruption intensity on tax enforcement effectiveness. Audit expertise is relatively stable and therefore is less likely to be affected by anti-corruption intensity.

In addition to 27 provinces and four province-level municipalities in the Chinese mainland, there are five cities with independent tax and finance planning systems, including Qingdao (in Shandong province), Ningbo (in Zhejiang province), Dalian (in Liaoning province), Xiamen (in Fujian province) and Shenzhen (in Guangdong province).

The yearbook, prepared annually by the SAT, contains detailed information about tax enforcement data for each province and major city in China. The hand-collected tax enforcement data are for overall tax deficiencies, and include all types of taxes.

Tax enforcement data from the China Tax Audits Yearbook ends in 2017.

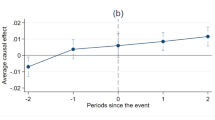

The sample year ends in 2017, which is the last year for which tax enforcement data are available. The starting years of investigations by the CCDI for all regions in China are from 2012 to 2015. Accordingly, we use two years before and two years after for the parallel trends test.

We also employ DID analysis to test the impact of anti-corruption intensity on tax enforcement effectiveness. Specifically, we use 2012 as a benchmark year to test whether our results hold if we focus on an exogenous shock to political officials. We classify firms in regions whose median anti-corruption intensity over the sample period is above the median for all regions as treatment firms (Treat = 1), and firms in all other regions as control firms (Treat = 0). We then create the time variable Post, which equals 1 for the years 2012 to 2017, and 0 for the years 2005 to 2011. The regression results based on thesetests are just confirm the main results.

We also use beforek (k = 1,2,3) and afterk (k = 1,2,3,4). The results are quite the same.

In the first-stage regression estimates, the F value is 44.80 (74.14) when we use TAR (TDE) as the tax enforcement measure. Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis that these variables are weak instruments. In addition, the Sargan value is 9.15 (p = 0.0103), rejecting the overidentified restrictions criterion.

All the awards are for tax agents’ performance.

For this analysis, we focus on the year of service for which the tax agent is granted the award, not when the actual award is received (usually 2 years later). Therefore, the sample begins in 2012 when the anti-corruption campaign begins, and ends in 2016, the last year for which award information is available (the China Tax Audits Yearbook ends in 2017).

2005 is the earliest year with tax enforcement data available from the China Tax Audits Yearbook.

We thank for this suggestion from one of the reviewers.

References

Adelopo, I., & Rufai, I. (2020). Trust deficit and anti-corruption initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 163(3), 429–449.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications.

Al-Hadi, A., Taylor, G., & Richardson, G. (2021). Are corruption and corporate tax avoidance in the United States related? Review of Accounting Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09587-8

Argandoña, A. (2007). The United Nations convention against corruption and its impact on international companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 481–496.

Ayers, B. C., Seidman, J. K., & Towery, E. (2019). Tax reporting behavior under audit certainty. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(1), 326–358.

Azim, M. I., & Kluvers, R. (2019). Resisting corruption in Grameen bank. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(3), 591–604.

Bentham, J. (1791). Panopticon: The Inspection-House: Containing the Idea of a New Principle of Construction Applicable to Any Sort of Establishment. Which Persons of Any Description Are to Be Kept under Inspection: And in Particular to Penitentiary-Houses, Prisons, Houses of Industry, and Schools: With a Plan of Management Adapted to the Principle: In a Series of Letters.

Bradshaw, M., Liao, G., & Ma, M. S. (2019). Agency costs and tax planning when the government is a major shareholder. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 67(2–3), 255–277.

Cai, H., Fang, H., & Xu, L. C. (2011). Eat, drink, firms, government: An investigation of corruption from the entertainment and travel costs of Chinese firms. Journal of Law and Economics, 54(1), 55–78.

Calderon, R., Álvarez-Arce, J. L., & Mayoral, S. (2009). Corporation as a crucial ally against corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 319–332.

Chen, H., Tang, S., Wu, D., & Yang, D. (2021). The political dynamics of corporate tax avoidance: The Chinese experience. The Accounting Review, 96(5), 157–180.

Chen, J., Duh, R.-R., Wu, C.-T., & Yu, L.-H. (2019). Macroeconomic uncertainty and audit pricing. Accounting Horizons, 33(2), 75–97.

Chen, S. X. (2017). The effect of a fiscal squeeze on tax enforcement: Evidence from a natural experiment in China. Journal of Public Economics, 147, 62–76.

Chen, T., & Kung, K. S. (2019). Busting the “princelings”: The campaign against corruption in china’s primary land market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(1), 185–226.

Chow, T., Pittman, J., Wang, M., & Zhao, L. (2020). Spillover effects of clients’ tax enforcement on financial statement auditors: Evidence from a discontinuity design. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3487193

Cleveland, M., Favo, C. M., Frecka, T. J., & Owens, C. L. (2009). Trends in the international fight against bribery and corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 199–244.

Cole, M. A., Elliott, R. J., & Zhang, J. (2009). Corruption, governance and FDI location in China: A province-level analysis. The Journal of Development Studies, 45(9), 1494–1512.

Colonnelli, E., & Prem, M. (2022). Corruption and firms. The Review of Economic Studies, 89(2), 695–732.

Desai, M. A., Dyck, A., & Zingales, L. (2007). Theft and taxes. Journal of Financial Economics, 84(3), 591–623.

Ding, H., Fang, H., Lin, S., & Shi, K. (2020). Equilibrium consequences of corruption on firms: evidence from China’s anti-corruption campaign. NBER Working Papers 26656, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Dong, B., & Torgler, B. (2013). Causes of corruption: Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 26, 152–169.

Ehrlich, I. (1996). Crime, punishment, and the market for offenses. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(1), 43–67.

Fan, J. P., Guan, F., Li, Z., & Yang, Y. G. (2014). Relationship networks and earnings informativeness: Evidence from corruption cases. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 41(7), 831–866.

Frank, M. M., Lynch, L. J., & Rego, S. O. (2009). Tax reporting aggressiveness and its relation to aggressive financial reporting. The Accounting Review, 84(2), 467–496.

Ghoul, S. E., Guedhami, O., & Pittman, J. (2011). The role of IRS monitoring in equity pricing in public firms. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(2), 643–674.

Giannetti, M., Liao, G., You, J., & Yu, X. (2021). The externalities of corruption: Evidence from entrepreneurial activity in China. Review of Finance, 25(3), 629–667.

Goldman, J., & Zeume, S. (2021). Who benefits from anti-corruption enforcement. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3745751

Griffin, J. M., Liu, C., & Shu, T. (2022). Is the Chinese anticorruption campaign authentic? Evidence from Corporate Investigations. Management Science, 68(10), 7248–7273.

Hauser, C. (2019). Fighting against corruption: Does anti-corruption training make any difference? Journal of Business Ethics, 159(1), 281–299.

He, K., Pan, X., & Tian, G. G. (2017). Political connections, audit opinions, and auditor choice: Evidence from the ouster of government officers. Auditing-a Journal of Practice & Theory, 36(3), 91–114.

Hoopes, J. L., Mescall, D., & Pittman, J. A. (2012). Do IRS audits deter corporate tax avoidance? The Accounting Review, 87(5), 1603–1639.

Hope, O., Yue, H., & Zhong, Q. (2020). China’s anti-corruption campaign and financial reporting quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 37, 1015–1043.

Huang, C., & Chang, H. (2019). Ownership and environmental pollution: Firm-level evidence in China. Asia-Pacific Management Review, 24(1), 37–43.

Husted, B. W. (2002). Culture and international anti-corruption agreements in Latin America. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(4), 413–422.

Iacobucci, D., Schneider, M. J., Popovich, D. L., & Bakamitsos, G. A. (2017). Mean centering, multicollinearity, and moderators in multiple regression: The reconciliation redux. Behavior Research Methods, 49(1), 403–404.

Jin, X., Chen, Z., & Luo, D. (2019). Anti-corruption, political connections and corporate responses: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 57, 1–20.

Kim, F., & Zhang, L. (2016). Corporate political connections and tax aggressiveness. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(1), 78–114.

Kong, D., & Qin, N. (2021). China’s anti-corruption campaign and entrepreneurship. Journal of Law and Economics, 64(1), 153–180.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 15(1), 222–279.

Li, B., Wang, Z., & Zhou, H. (2022). China’s anti-corruption campaign and credit reallocation from SOEs to non-SOEs. PBCSF-NIFR research paper (17-01).

Lin, C., Morck, R., Yeung, B., & Zhao, X. (2016). Anti-corruption reforms and shareholder valuations: Event study evidence from China. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2729087

Lin, K. Z., Mills, L. F., Zhang, F., & Li, Y. (2018). Do political connections weaken tax enforcement effectiveness? Contemporary Accounting Research, 35, 1941–1972.

Liu, Q., Luo, W., & Rao, P. (2015). The political economy of corporate tax avoidance. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2709608

Liu, X., Shu, H., & Wei, J. (2017). The impacts of political uncertainty on asset prices: Evidence from the Bo scandal in China. Journal of Financial Economics, 125(2), 286–310.

Luo, Y. (2005). An organisational perspective on corruption. Management and Organisation Review, 1(1), 119–154.

Mailath, G. J. (1993). Endogenous sequencing of firm decisions. Journal of Economic Theory, 59(1), 169–182.

Nessa, M. L., Schwab, C. M., Stomberg, B., & Towery, E. (2020). How do IRS resources affect the corporate audit process? The Accounting Review, 95(2), 311–338.

Nie, H., & Wang, M. (2016). Are foreign monks better at chanting? The effect of ‘airborne’SDICs on anti-corruption. Economic and Political Studies, 4(1), 19–38.

Noldeke, G., & Samuelson, L. (1997). A dynamic model of equilibrium selection in signaling markets. Journal of Economic Theory, 73(1), 118–156.

Page, J. (2011). “Children of the Revolution,”. Wall Street Journal, November 26. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424053111904491704576572552793150470.

Pan, X., & Tian, G. (2017). Political connections and corporate investments: Evidence from the recent anti-corruption campaign in China. Journal of Banking & Finance. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.03.005

Polinsky, A. M., & Shavell, S. (1979). The optimal tradeoff between the probability and magnitude of fines. American Economic Review, 69(5), 880–891.

Pomeranz, D., & Vila-Belda, J. (2019). Taking state-capacity research to the field: Insights from collaborations with tax authorities. Annual Review of Economics, 11(1), 755–781.

Qu, G., Sylwester, K., & Wang, F. (2018). Anticorruption and growth: Evidence from China. European Journal of Political Economy, 55(55), 373–390.

Slemrod, J., Blumenthal, M., & Christian, C. (2001). Taxpayer response to an increased probability of audit: Evidence from a controlled experiment in Minnesota. Journal of Public Economics, 79(3), 455–483.

Spence, M. (1978). Job market signaling. Uncertainty in economics (pp. 281–306). Academic Press.

Stigler, G. J. (1970). The optimum enforcement of laws. Journal of Political Economy, 78(3), 526–536.

Wang, F., Xu, L., Zhang, J., & Shu, W. (2018). Political connections, internal control and firm value: Evidence from China’s anti-corruption campaign. Journal of Business Research, 86, 53–67.

Wang, X., Fan, G., & Yu, J. (2016). NERI index of marketization of China’s provinces 2016 report. Social Sciences Academic Press.

Weismann, M. F., Buscaglia, C. A., & Peterson, J. (2014). The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act: Why it fails to deter bribery as a global market entry strategy. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(4), 591–619.

Xu, G., & Yano, G. (2017). How does anti-corruption affect corporate innovation? Evidence from recent anti-corruption efforts in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45(3), 498–519.

Zhang, J. (2018). Public governance and corporate fraud: Evidence from the recent anti-corruption campaign in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 375–396.

Zhou, L., Liu, C., & Li, X. (2011). Tax effort, tax bureaus and the puzzle of the abnormal tax growth. China Economic Quarterly (in Chinese), 11(1), 1–18.

Funding

The work was supported Humanities and Social Sciences project of China’s Ministry of Education [20YJC630098] and Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province [2019S015].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Variables | Definitions |

|---|---|

ETR | One-year effective tax rate, defined as annual income tax expense divided by annual pretax income |

TAR | Tax audit rate, defined as the number of corporate income tax audits conducted divided by the number of corporate income tax returns filed |

TDE | Tax deficiencies, i.e., economic consequences of the tax audits in terms of additional tax payments for tax underreporting, measured by the amount of tax deficiencies settled divided by the amount of regional tax revenues |

AC | Anti-corruption intensity, measured as the numbers of investigated persons divided by the total population (million) in that area |

ROA | Return on assets, net income divided by total assets |

LNA | Firm size, the natural logarithm of the firm’s year-end total assets |

LEV | Leverage, total liabilities divided by total assets |

PPE | Plant, property, and equipment, net PPE divided by total assets |

INTANGI | Intangibles, intangible assets divided by total assets |

INV | Inventory, inventory divided by total assets |

CASH | Cash holdings, year-end cash holdings divided by total assets |

EQINCI | Equity in earnings, equity income divided by total assets |

MB | Market value of equity divided by book value of equity |

DA | Discretionary accruals estimated from the cross-sectional Jones model |

SOE | Ownership structure, state-owned enterprises or non- state-owned enterprises |

BIG4 | Auditor type, Big 4 auditor or non-Big4 auditor |

BSIZE | Board size, the number of board members |

INSTITUTION | The Index of Marketization for China’s Provinces, compiled by Wang et al. (2016) |

InvestigationAFT | A dummy that equals one in affected province j for both the investigation year t and the following years, and zero for all other years |

CHARITYU | The number of charity universities in a province/city, measured as the number of church universities founded by Christian missionaries in each region by 1920 |

CONCESSION | The incidence of concessions in a province/city, a dummy variable indicating whether there was once a concession or leased territory in the region |

AGENTS | The number of the agents being awarded |

LNAGENTS | The natural logarithm of the number of the agents being awarded plus 1 |

RAGENTS | The ratio of the number to total population in that region |

IAGENTS | The incidence of agents being awarded, an indicator variable that equals 1 if at least one agent is granted an award in a region-year, and 0 otherwise |

IDEPTS | The incidence of departments being awarded, an indicator variable that equals 1 if at least one department is granted an award in a region-year, and 0 otherwise |

IAWARD | The incidence of agents or departments being awarded, an indicator variable that equals 1 if at least one agent or one department is granted an award in a region-year, and 0 otherwise |

LNGDP | The natural logarithm of GDP |

LNPOPUL | The natural logarithm of population |

AWARDTYPE | The type of award; equals 2 if the award is at the national level (from the SAT), 1 if the award is at the regional level, and 0 if there is no award |

change | Provincial secretary changes, equals 1 if the local provincial secretary changes, and 0 otherwise |

TIP-OFF | Number of tip off case divided by the number of total taxpayers in a region |

NUMBER | Ratio of number of tax auditors to the number of total tax agents in a region |

PARTY | Ratio of number of Communist Party member to the number of total tax auditors in a region |

AC1 | Alternative anti-corruption intensity, measured as the numbers of investigated persons divided by the total companies in that area |

TAXRATE | Nominal tax rate employed by a firm |

DTAR | Dummy TAR measure, equals one if TAR (TDE) is above its median, and zero otherwise |

DTDE | Dummy TAR measure, equals one if TAR (TDE) is above its median, and zero otherwise |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, C., Cheng, M. & Lobo, G.J. How Do Tax Agents Respond to Anti-corruption Intensity?. J Bus Ethics 190, 137–164 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05398-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05398-w