Abstract

Metaphysicians who are aware of modern physics usually follow Putnam (1967) in arguing that Special Theory of Relativity is incompatible with the view that what exists is only what exists now or presently. Partisans of presentism (the motto ‘only present things exist’) had very difficult times since, and no presentist theory of time seems to have been able to satisfactorily counter the objection raised from Special Relativity. One of the strategies offered to the presentist consists in relativizing existence to inertial frames. This unfashionable strategy has been accused of counterfeiting, since the meaning of the concept of existence would be incompatible with its relativization. Therefore, existence could only be relativistically invariant. In this paper, I shall examine whether such an accusation hits its target, and I will do this by examining whether the different criteria of existence that have been suggested by the Philosophical Tradition from Plato onwards imply that existence cannot be relativized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

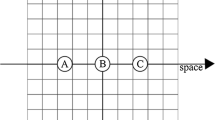

That is, when S and R are the relations of simultaneity and reality-existence (Thyssen 2020, p. 26):

Best supporter: Routley (1980, pp. 389–390, 397–400; 1997, pp. 315–316). The rejection of ‘There Are No Privileged Observers’ is also briefly and positively discussed in Sklar (1974, pp. 272–275); Hinchliff (1996, pp. 129–132 and 2000, pp. S578-S579)—see also Dainton (2010, pp. 331–332) and Thyssen (2020, pp. 52–54)

Fine (2009) prefers to use the word ‘reality’ rather than ‘existence’: roughly, while existence logically corresponds to the ‘thin’ and ontologically unloaded sense of the quantified expression ‘there is’ (Fine does so to keep the orthodox and Quinean terminological usage), reality corresponds to its ‘thick’ and ontologically loaded meaning.

On Routley’s Plurallism and SR, see Routley (1997, pp. 315–316).

It should be remarked that Fine (2005a, p. 283 n.5) argues for the fact that the plurality of possible worlds of Lewis (1986) is not semantically analogous to the pluralistic reality defended in Fine (2005a), that is, Fragmentalism is formally not alike to Modal Realism (for instance, Modal Fragmentalism does not involve a counterpart semantics as Modal Realism). Routley (1997, p. 24) too distances himself from Lewis’ pluralism.

On this point, they follow Descartes (amongst others) who had always refused to provide a definition for existence, see AT IX-2 28–29 and Bardout (2013, p. 417).

See Chalmers (2022, pp. 108–115, 480–481) for a listing of reality-criteria very similar to Routley’s listing of existence-criteria and mine: causal power, mind-independence, non-illusoriness, genuineness, observability, measurability, theoretical utility, actuality, truth, factuality, objectivity, evidence-independence, originality, fundamentality, etc. On the meaning of ‘reality’ from a philosophical-linguistic standpoint, see also Reynolds (2006).

Kant, AK 3.400: ‘every existential proposition is synthetic’. AK 3.93 includes existence (Dasein) and non-existence (Nichtsein) amongst the a priori categories (under the higher-order category of modality that also includes the two pairs < possibility, impossibility > and < necessity, contingency >) of Understanding of which the attribution is synthetic rather than analytic (and so, of which the attribution is not trivial). Kant’s reading of ‘existence’ (which is only a logical predicate, it has no determining import—such a distinction being very close to the Meinongian dualities < characterizing vs. non-characterizing properties > and < nuclear vs. extranuclear properties > , see Routley 1980, pp. 180–187, 264–268, and is reminiscent of Hume, THN, I.2 s.6) is a kind of modal criterion (A1), see AK 2.72–77, 3.400–402. (‘AK’ stands for ‘Akademie-Ausgabe. Kant Gesammelte Schriften herausgegeben von de Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften’)

Such a criterion of existence appears in late scholasticism, see Bardout (2013, pp. 430–431).

See Marion WMJ, pp. 908–910 for a very short presentation of the debate between actualism and possibilism.

Cf. Williamson (2007, pp. 73–133) on the role of common understanding in philosophical debates. Of course, philosophers disagree about almost everything, but, even when they disagree, they share some uncontroversial understanding of the technical words they use (they do not ‘change the subject’, as Quine 1986, pp. 80–85 says, while they support a heterodox view in a philosophical or logical quarrel).

Routley (1980, pp. 204–207) distinguishes between the (actual) factual world T and the (actual) referential world G, the objectual domain of the second being inhabited only by existent items, while the objectual domain of the first includes both existent and non-existent items. Therefore, insofar as all true sentences in G are pure extensional statements about existing items, a true sentence about things that do not exist like ‘the round square is round’ is false in G, but true in T: there are facts about the round square in T, but not in G.

Indeed, the proponents of suppositional logic (e.g. Buridan, Lambert of Auxerre, Marsilius of Inghen, William of Sherwood, Peter of Spain, Albert of Saxony, and Paul of Venice) use a proto-Meinongian device called ‘ampliatio’ to select non-existing items as referents within true propositions. Translated in modern philosophical dialect, ampliation is a contextual extension of the scope of quantifiers beyond what presently and actually exists (the opposite device of restrictio being a contextual reduction of their scope). Usually, those who accept ampliative logics (the philosophers mentioned above contra Ockham) believe that tense (‘was’, ‘will be’), modal (‘can’, ‘may’, ‘is possible’), and intentional (‘is conceived’, ‘is imagined’, ‘is understood’) verbs possess an ampliative force that permit to ‘quantify’ over past, future, merely possible or imaginary items. For the use of ampliation in relation to medieval semantic theories of truth, see the discussion of the nine ways for a proposition to be true in Paul of Venice (1978) Logica Magna: de veritate et falsitate propositionis.

See Aristotle, Physics, IV.1 208a29-31 for an old testimonia about such an idea: to exist is to be in some physical place. For an early defence of the thesis that existence means nothing but having a spatio-temporal spot, see Crucius (1753, §§46–48) criticized in AK 2.76–77

See Routley (1980, pp. 710–712) on the ‘location’ of plural objects made by stipulation.

See Marion WMJ, pp. 929–936 for a brief discussion of such a contingentist puzzle.

Kant, AK 2.73–74, 3.401 is reminiscent of such a linkage between existence and being posited: ‘Being is obviously not a real predicate, i.e. a concept of something that could add to the concept of a thing. It is merely the positing of a thing or of certain determinations in themselves’. (AK 3.401, translation from Guter P. & Wood, A. W.)

For the record, another view can be linked to Empiricist and Berkeleyan ones, namely that of Hacking (1983) according to which to exist is to be manipulable, i.e. to be able to be used to effectively interfere with the world (in Hacking 1983, p. 23 words: ‘so far as I’m concerned, if you can spray them then they are real’ … so electrons and other theoretical items are real).

To borrow the joke from Russell (1905, p. 485): ‘by the law of excluded middle, either “A is B” or “A is not B” must be true. Hence either “the present King of France is bald” or “the present King of France is not bald” must be true. Yet if we enumerated the things that are bald, and then the things that are not bald, we should not find the present King of France in either list. Hegelians, who love a synthesis, will probably conclude that he wears a wig’. (Russell’s answer is obviously quite unsatisfactory).

Provisionally, Routley (1980, pp. 720–732) attempts to revise such a position to make it more satisfactory.

The brute Characterization Postulate (CP) needs to be amended to address various challenges. Routley (1980) revises CP by distinguishing characterizing from non-characterizing properties (or nuclear and extranuclear properties), while Berto (2013) and Priest (2016) defend that CP must be modalized as follows: for any condition α[x] with free variable x, some item exactly satisfies α[x] at least at some intentionally accessible world. For a survey, see Berto (2013, pp. 85–151).

This conclusion is far for having limited consequences only in metaphysics of physics (special and general relativity, gauge theories, etc.). Another hot spot, for instance, is the question whether virtual or digital objects exist in the full sense of the term or not. On this fashionable topic nowadays, see the opinionated Chalmers (2022).

References

Azzouni, J. (2004). Deflating existential consequence. A case for nominalismOxford: Oxford University Press.

Azzouni, J. (2010). Talking about nothing. Numbers, hallucinations and fictionsOxford: Oxford University Press.

Azzouni, J. (2017). Ontology without borders. Oxford University Press.

Bardout, J.-C. (2013). Penser l’existence. I. L’existence exposée – Époque médiévale. Paris: Vrin.

Baumgarten, A. G. (1757). Metaphysica, Editio IV, Hale Magdeburgicae, Impensis Carol. Herman, Hemmerde.

Berto, F. (2013). Existence as a real property. Springer, Dordrecht: The ontology of meinongianism.

Berto, F., & Plebani, M. (2015). Ontology and metaontology. A contemporary guide. London: Bloomsbury.

Bliss, R., & Priest, G. (2018). The geography of fundamentality: An overview. In R. Bliss & G. Priest (Eds.), Reality and its structure (pp. 1–33). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Callender, C. (2017). What makes time special? Oxford University Press.

Chalmers, D. J. (2022). Reality+. Virtual worlds and the problems of philosophy. London: Allen Lane.

Crucius, C. A. (1753). Entwurf der notwendigen Vernunft-Warbeiten, wiefern sie den zutfälligen entgegen gesetzt werden, Leipzig.

Dainton, B. (2010). Time and space (2nd ed.). Durham: Acumen.

Dorato, M. (2008). Putnam on time and special relativity: A long journey from ontology to ethics. European Journal for Analytic Philosophy, 4–2, 51–70.

Fine, K. (1984). Critical review of parsons’ non-existent objects. Philosophical Studies, 45–1, 95–142.

Fine, K. (2001). The question of realism. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1–1, 1–30.

Fine, K. (2003). The problem of Possibilia. In M. J. Loux & D. W. Zimmerman (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Metaphysics (pp. 161–179). Oxford University Press.

Fine, K. (2005a). Tense and reality. Modality And Tense (pp. 261–320). Oxford Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Fine, K. (2005b). Necessity and non-existence. Modality and Tense (pp. 321–354). Oxford Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Fine, K. (2009). The question of ontology. In D. J. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics (pp. 157–177). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Fine, K. (2012). Guide to ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical Grounding (pp. 37–80). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Gabriel, M., & Priest, G. (2022). Everything and nothing. Polity Press.

Gödel, K. (1949). “A remark about the relationship between relativity theory and idealistic philosophy”, Feferman, S. (ed.). 1990. Kurt Gödel. Collected Works, vol. 2(pp. 202–207). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Goodman, N. (1978). Ways of worldmaking. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Hacking, I. (1983). Representing and intervening. Cambridge University Press.

Hale, B. (2013). Necessary beings. An essay on ontology, modality, and the relations between them. Oxford University Press, Oxford. (pagination: Paperback edition of 2015).

Heidegger, M. (1927). Sein und Zeit, in 1977. Gesamtausgabe, Bd. 2, Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main.

Heidegger, M. (1928). Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der Logik im Ausgang von Leibniz, in 1978. Gesamtausgabe, Bd. 26, Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main.

Hinchliff, M. (1996). The puzzle of change. Philosophical Perspectives, 10, 119–136.

Hinchliff, M. (2000). A defense of presentism in a relativistic setting. Philosophy of Science, 67(Suppl), S575–S586.

Hinchliff, M. (1988). A defense of presentism, PhD Thesis, Princeton University.

Iaquinto, S., & Torrengo, G. (2022). Fragmenting reality. An essay on passage, causality and time. London: Bloomsbury.

Kahn, C. H. (1966). The greek verb ‘to be’ and the concept of being. Foundations of Language, 2, 245–265.

Le Bihan, B. (2018). Contre les défenses du présentisme par le sens commun. Igitur Arguments Philosophiques, 9–1, 1–24.

Lewis, D. (1986). On the plurality of worlds. Blackwell.

Marion, F. (2022). Seyn, ἕν, 道: Brevis tractatus meta-ontologicus de elephantis et testudinibus. Revue Philosophique de Louvain, 119–1, 1–51.

Marion, F. (2023a). Modalité et changement: δύναμις et cinétique aristotélicienne. PhD dissertation, Université catholique de Louvain.

Marion, F. (2023b). Welcome to the modalist jungle. Potentiality-based modality: Semantics and metaphysics, Draft. = Supplementary Essay 2 in Marion pp. 917–945.

McDaniel, K. (2017). The fragmentation of being. Oxford University Press.

Meinong, A. (1915). Über Möglichkeit und Wahrscheinlichkeit. Beiträge zur Gegenstandstheorie und Erkenntnistheorie = 1972. Haller, R., Kindinger R. & Chisholm, R. M. (eds.), Alexius Meinong Gesamtausgabe. Bd. 6. Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, Graz.

Nozick, R. (2001). Invariances. The structure of the objective world. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA-London.

Paul of Venice (Paulus Venetus). (1978). Logica Magna, Part. II Fascicule 6: Tractatus de veritate et falsitate propositionis & Tractatus de significato propositionis (eds. Del Punta, F. & McCord Adams, M.), Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Priest, G. (2016). Towards non-being. Second Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Prior, A. N. (1957). Time and modality. Being the John Locke Lectures for 1955–6 delivered in the University of Oxford. Oxford Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Putnam, H. (1967). Time and physical geometry. Journal of Philosophy, 64–8, 240–247.

Putnam, H. (1981). Reason, truth and history. Cambridge University Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1968). Ontological relativity. The Journal of Philosophy, 65–7, 185–212.

Quine, W. V. O. (1986). Philosophy of logic (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1948). “On what there is”, in 1953. From a logical point of view. 9 logico-philosophical essays (pp. 1–19). Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

Reynolds, S. L. (2006). Realism and the meaning of ‘real.’ Noûs, 40–3, 468–494.

Routley/Sylvan, S. (1980). Exploring Meinong’s jungle and beyond. Australian National University, Canberra.

Routley/Sylvan, S. (1997). Transcendental metaphysics. The White Horse Press, Cambridge.

Russell, B. (1903). Principles of mathematics. Cambridge University Press.

Russell, B. (1905). On Denoting. Mind, 14, 479–493.

Salmon, N. (1989). The logic of what might have been. Philosophical Review, 98, 3–34.

Schaffer, J. (2009). On What Grounds What. In D. J. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics (pp. 347–383). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Sellars, W. (1962). Time and the world order. In H. Feigl & G. Maxwell (Eds.), Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science (Vol. 3, pp. 527–616). University of Minnesota Press.

Sklar, L. (1974). Space, time, and spacetime. University of California Press.

Smart, J. J. C. (1979). “The reality of the future”, typescript. Canberra.

Thyssen, P. (2020). The block universe. A philosophical investigation in four dimensions. PhD dissertation, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

van Inwagen, P. (1998). Meta-ontology. Erkenntnis, 48, 233–250.

Varzi, A. C. (2005). Ontologia. Roma-Bari: Editori Laterza.

Voltolini, A. (2006). How ficta follow fiction. Springer, Dordrecht: A syncretistic account of fictional entities.

Wedgwood, R. (2007). The nature of normativity. Oxford Clarendon Press.

Whitehead, A. N. (1929). Process and reality. Macmillan, London: An essay in cosmology.

Whitehead, A. N., & Russell, B. (1910). Principia mathematica (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

Williams, D. C. (1962). Dispensing with existence. Journal of Philosophy, 59–23, 748–763.

Williamson, T. (2007). The philosophy of philosophy. Blackwell.

Williamson, T. (2013). Modal logic as metaphysics. Oxford University Press.

Wolff, C. (1730). Philosophia prima sive ontologia. Frankfurt-Leipzig (= GW II.3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

‘Part. 2: Philosophy of Science’ shall be a companion paper written with Kévin Chalas (Institut supérieur de Philosophie/CEFISES, Université catholique de Louvain) whom I would like to thank for helpful discussions.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Marion, F. Existence Is Not Relativistically Invariant—Part 1: Meta-ontology. Acta Anal (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-024-00586-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-024-00586-3