Abstract

In Strategic Justice, Peter Vanderschraaf introduces a “Baseline Consistency” criterion for Justice as Mutual Advantage. This criterion requires assessing how well individuals fare under existing conventions with how well they would fare under hypothetical social conditions. However, this comparison requires the impossible. Under different social conditions, individuals would have different preferences and different interests. As such, we cannot make any direct comparison between how well an individual fares across the two social conditions. The standard of assessment would change from one context to the other. In order to apply the Baseline Consistency criterion, Vanderschraaf would need to justify an interpersonally valid standard for individual welfare, but this is incompatible with his Neo-Hobbesian method. If he abandoned the Baseline Consistency criterion, however, Vanderschraaf faces the “too many equilibria” problem. Conventions that are clearly objectionable would be considered just.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As discussed below, there are different ways of interpreting the baseline consistency requirements. My concern persists across difference interpretations, but I believe this way of understanding the criterion makes for the strongest view.

For more on arguments against a status quo bias, see (Melenovsky 2019a).

I will refer to “basic” conventions because I believe that Vanderschraaf needs to narrow the set of conventions that he is concerned with in some way. There are conventions that emerge from all kinds of interaction, and not all these conventions constitute the demands of justice. For example, elevator use is important at any urban university with tall buildings. Between classes, there will be both coordination and competition for elevator spots, and people will develop certain conventions that regulate behavior. Yet, these conventions would not express the demands of justice. As such, there must be a way of distinguishing the conventions that constitute justice from those that do not. I use the phrase “basic” to emphasize the subset of conventions that constitute justice.

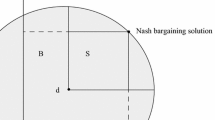

Vandershraaf defines “SN” as “For a given population N the requirements SN of an incumbent justice as mutual advantage system define a body of conventions that together define a complex social equilibrium that is also a Pareto improvement over the free-for all σO*” (311).

As he says “I still cannot believe that it is helpful to speak as if interpersonal comparison of utility rest upon scientific foundations—that is, upon observation or introspection. I am perhaps more alive than before to the extraordinary difficulties surrounding the whole philosophy of valuation. But I still think, when I make interpersonal comparisons…that my judgments are more like judgments of value than judgments of verifiable fact” (Robbins, 1938, p. 640).

“As we have seen, even if only as few as one or two such normatively distinguished options or states of affairs are identified, the underdetermination between rival attributions of utilities to persons can be broken—of course, in a non-empirical way, but nonetheless, by stipulation, in a normatively significant one.” (List, 2003, p. 254).

Recognizing, of course, that the pursuit of justice is a “rugged landscape” such that moving closer to the ideal might, in fact, lower how just the world is. See (Gaus, 2016; Melenovsky, 2019b). For those with this worry, you can simply amend my suggestion and replace “an ideal for our basic conventions” with “a way to measure to which conventions are better or worse.”.

I say this while recognizing that the principles themselves might need to be justified to actual people whose values are determined by a social context. A liberal view would want principles of justice to be acceptable to actual people with socially-determined preferences. Rawls attempts to do this, for example, by providing a justification for Justice as Fairness that is acceptable to reasonable people that face the burdens of judgment.

This is explored in more depth in my dissertation, “A Mooring for Ethical Life” (2014).

References

Barrett, J. (2019). Interpersonal comparisons with preferences and desires. Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 18(3), 219–241.

Binmore, K. (2003). Interpersonal comparison of utility. In D. Ross & H. Kincaid (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of economics. Oxford University Press.

Elster, J., & Roemer, J. (1991). In J. Elster, & J. Roemer (Eds.), Interpersonal comparisons of well-being. Cambridge University Press.

Gaus, J. (2015). On dissing public reason: A reply to enoch. Ethics, 125(4), 1078–1095.

Gaus, J. (2016). Tyranny of the Ideal. Princeton University Press.

Greaves, H., & Lederman, H. (2018). Extended preferences and interpersonal comparisons of well-being. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 96(3), 636–667.

Griffin, J. (1986). Well-being: Its meaning. Clarendon Press.

Hammond, P. (1991). Interpersonal comparisons of utility: why and how they are and should be made. In J. Elster & J. Roemer (Eds.), Interpersonal comparisons of well-being. Cambridge University Press.

Hausman, D. (1995). The impossibility of interpersonal utility comparisons. Mind, 104(415), 473–490.

List, C. (2003). Are interpersonal comparisons of utility indeterminate? Erkenntnis, 58, 229–260.

MacAskill, W., Cotton-Barratt, O., & Ord, T. (2020). Statistical normalization methods in interpersonal and intertheoretic comparisons. The Journal of Philosophy, 117(2), 61–95.

Melenovsky, C. M. (2014). A mooring for ethical life: Assessing the basic structure of society.

Melenovsky, C. M. (2019a). The status Quo in Buchan’s constitutional contractarianism. Homo Oeconomicus, 36, 2.

Melenovsky, C. M. (2019b). The value of a non-ideal. Social Theory and Practice, 45(3), 427–450.

Rawls, J. (1971). Theory of justice, original text. Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (2001). Justice as fairness: A restatement. Harvard University Press.

Robbins, L. (1938). Interpersonal comparisons of utility: A comment. The Economic Journal, 48(192), 635–641.

Sen, A. (1970). Collective choice and social welfare. Holden Day.

Sepielli, A. (2013). Moral uncertainty and the principle of equity among moral theories. Philosophy and Phenomeological Research, 86(3), 580–589.

Vanderschraaf, P. (2019). Strategic justice.

Vanderschraaf, P. (2021). Precis of Strategic justice: Convention and problems of balancing divergent interests. Philosophical Studies, 178, 1701–1705.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Jeppe von Platz in working through the argument of this chapter. I also appreciated the helpful comments from two anonymous reviewers, one who helpfully pushed me to engage with more recent arguments in defense of interpersonal comparisons of utility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Melenovsky, C.M. Interests from and in conventions. Synthese 200, 41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03589-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03589-y