Abstract

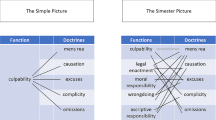

Negligence is a problematic basis for being morally blamed and punished for having caused some harm, because in such cases there is no choice to cause or allow—or risk causing or allowing—such harm to occur. The standard theories as to why inadvertent risk creation can be blameworthy despite the lack of culpable choice are that in such cases there is blame for: (1) an unexercised capacity to have adverted to the risk; (2) a defect in character explaining why one did not advert to the risk; (3) culpably acquiring or failing to rid oneself of these defects of character at some earlier time; (4) flawed use of those practical reasoning capacities that make one the person one is; or (5) chosen violation of per se rules about known precautions. Although each of these five theories can justify blame in some cases of negligence, none can justify blame in all cases intuitively thought to be cases of negligence, nor can any of these five theories show why inadvertent creation of an unreasonable risk, pure and simple, can be blameworthy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is a version of the view that whatever was actual must have been possible. It probably supposes some objective notion of probability and risk. For an introduction to objective versions of the semantics of the probability calculus, see Gilles (2000).

Model Penal Code '2.02(2)(d).

A much quoted saying from the late Judge Calvert Magruder’s Torts class at the Harvard Law School, reported in his retirement farewell, Magruder (1959, p. 7).

Alexander and Ferzan (2009a, p. 69).

Magruder (1959, p. 7).

Model Penal Code '2.02(2)(c). The language quoted in the text was thought to be an alternative way of wording the requirement of Tentative Draft No. 4 of section 2.02 (2) (c), which required for recklessness a disregard of the risk that ‘involved culpability to a high degree.’ Model Penal Code and Commentaries, p. 237 n. 15. By contrast, the culpability judgment needed for negligence is only whether the failure of a defendant to perceive the risk ‘was serious enough to be condemned,’ revealed ‘fault,’ or ‘justifies condemnation.’ Id., p. 241.

Alexander and Ferzan (2009a, pp. 69, 78 n. 25).

Ferzan (2001).

Moore (1997, pp. 548–592).

Id, at pp. 404–411.

Hart (1968, pp. 156–157).

Id., pp. 154–156. Individualizing capacity judgments is discussed in Westen (2008).

Duff (2009, pp. 70–72). One interpretation of Joseph Raz’s recently published account of the culpability of negligence is that it is a version of Hart’s unexercised capacity view, although Raz substitutes his own vocabulary by speaking of negligence as a ‘malfunctioning competence.’ Raz (2010). If Raz’s view is not just that of Hart’s, then it is a version of the account provided by George Sher (2009), which we discuss in section “Negligence Culpability for Uncharacteristic Failures in Practical Reasoning Capacities”.

Duff (2009, p. 71).

Id., p. 72.

Model Penal Code '2.02(2).

Doug Husak finds this to be a ‘pivotal topic’ that is ‘radically undertheorized’ by those engaged in the debate about the punishability of negligence, a situation he deplores as ‘scandalous.’ Husak (2011). Although we would be happy to pretend that our examination of this question in this section is all new, in fact what follows is a summary of our own and others’ prior published work on just what ‘awareness’ does mean.

Model Penal Code '2.02(7). George Fletcher points out that this builds some inadvertence into intentional wrongdoing, viz, that the actor need not advert to the wrongness of what he does but only to the factual nature of what he does. Fletcher (1971, pp. 420–423).

Model Penal Code '2.02(2)(c). Ken Simons points out that resolving this ambiguity the way we do—which is to require awareness only of the type of risk but not of its magnitude or lack of justification for running it—results in there being some inadvertence being built into recklessness. Simons (2009, pp. 290–291).

Stephen Garvey thinks of these as negligence cases (so long as the belief is the product of a desire over which the actor has doxastic self-control). See Garvey (2006, pp. 337–338), Garvey (2009, pp. 286–288). Alexander and Ferzan seemingly would class them as reckless. Alexander and Ferzan (2009b, pp. 292–293). We think there is a threshold of vividity that divides recklessness from negligence, although it is a sliding scale threshold, varying with the degrees of imbalance between risk and the reason for running of the risk.

E.g., Dennett (1978). See also Husak (2011). As Sher writes, even if the contents of an agent’s consciousness include “both what an agent is focusing on and what he is passively aware of . . . these items still represent only the tiniest fraction of the information to which he must take himself to have access in order to carry out his task.” Sher (2009, p. 127).

For an argument that these beliefs are also the product of active construction, see Pillsbury (1996, pp. 141–150).

Dennett (1969, pp. 114–131). Dennett calls the phenomenological and the dispositional senses of ‘awareness,’ ‘awareness1’ and ‘awareness2’.

An old and well-known observation of William James: ‘It is a general principle in psychology that consciousness deserts all processes where it can no longer be of use….We grow unconscious of every feeling which is useless as a sign to lead us to our ends, and where one sign will suffice others drop out, and that one remains to work alone.’ James (1890, Vol. 2, p. 496).

A conclusion Doug Husak also reaches about such cases. See Husak (2011).

As with the threshold of vividity for phenomenological awareness, here too we would think a sliding scale would be appropriate, the scale trading off between the kind of awareness the actor has of the risk, and the degree of imbalance there is between risk/reason for running the risk.

Admittedly the criminal law doctrines about willful blindness are focused on when we should classify such phenomenon as knowing (rather than reckless) wrongdoing. Yet the criminal law distinguishes result elements from circumstance elements of the actus reus for purpose of applying its willful blindness doctrines. Model Penal Code '2.02(7) regards willful blindness with respect to results as recklessness, not knowledge, which is why we find the criminal law to be in accord with our views here. See Model Penal Code and Commentaries, p. 248.

‘A court can properly find willful blindness only where it can almost be said that the defendant actually knew.’ United States v. Jewell, 532 F.2d 679 (9th Cir. 1976).

A version of the facts in Jewell. See generally Johnson (2006) for a discussion of situations where an actor both believes and disbelieves some proposition.

The locus classicus of self-deception remains Herbert Fingarette (1969).

As another commentator has concluded, in this context, ‘self deception [consists of] the neat but real mental trick of being aware and not being aware of something at the same time.’ Tasiltz (2009, p. 289).

On the idea of unconscious mental states generally, see Moore (1984, pp. 126–142, 249–280); on the idea of unconscious beliefs specifically, see id., pp. 295–298, 325–331. The idea of unconscious belief that Moore defends is one whereby a mental state: (1) is a mental state of a person because of its (in principle) recapturability in conscious experience; and (2) is a belief state because it both plays the functional role of beliefs in the explanation of behavior, and shares the physical structure(s) of such functionally specified states. Jerome Hall explores briefly whether unconscious beliefs should make us consider the negligent actor as having (in some sense) adverted to the risk, concluding (as do we) in the negative. Hall (1963).

Gary Watson too finds that ‘the idea of an unexercised capacity is much more difficult to make sense of than it initially appears.’ Watson (1977, p. 317).

Or not so subtle differences. J.L. Austin, for example, purported to discover an ability sense of ‘could,’ an opportunity sense of ‘could,’ and an all-out sense of ‘could.’ Austin (1961, p. 129).‘Could’ in the last two senses would not of course by synonymous with ‘ability.’ John Maier (2010) explores some differences between powers and abilities. See also Van Inwagen (1983, pp. 8–13), for further distinctions.

See, e.g., Mele (2003).

Keith Lehrer’s classic article, Lehrer (1976), is very good in its exploration of this.

See id.

This, on the plausible supposition that to have an ability to A requires that one would succeed in A-ing under some conditions. Contrary to Austin (1961), such success-conditions need not guarantee success in all cases, because the list of such conditions will always be incomplete vis-à-vis ruling out possible preventers of success. ‘Sufficient’ in ordinary English is always incomplete in just this way too.

A feature noted early on by Richard Taylor (1960).

We in fact have our doubts, for there seem to be too wide a class of excuses (like ignorance, mistake, insanity, diminished capacity, intoxication, infancy) to be accounted for by the ‘if he had chosen otherwise’ condition. The constraint excuses have long been the favorite of followers of Hume on this conditional (e.g., Schlick 1962). Yet even for duress and natural necessity, there are lack of opportunity versions of these defenses that do not easily get separated out by the choice condition. Someone who is not at all ‘unhinged’ by the fear a threat arouses (but who nonetheless does have very high opportunity costs attached to not doing what the threatener wants) can make causally effacious choices; what he lacks is the ability to make the choice that he wants. This suggests that an additional principle, ‘could have done (or chosen) otherwise if he had wanted to do (or choose) otherwise,’ is required. See Kane (1998, pp. 53–54, 56–58).

See the discussion and citations in Moore (2009, chapter 16).

Smith, M. (2004).

This perhaps plays on the general capacity the actor has.

See Moore (1997, Chapters 12 and 13).

This is assumed by Smith in his ‘Rational Capacities’ article (Smith, M. 2004). If an actor has an adequate information base, Smith thinks, he could have adverted to a thought that he in fact did not advert to. For Smith, recall, this is even true of the actor who ‘blanks’ on the thought when asked a question where the thought would have been an appropriate answer.

Even if one is not a conditionalist about capacity judgments, we think analogous context-sensitivities and possible worlds-induced vagueness will infect these (supposedly unconditional) capacity judgments. Thus, Keith Lehrer argued against conditions being implicit in ‘can’ and ‘could,’ yet ended up having to find ‘restrictions’ on possibilities, and ‘accessibility’ of possible worlds, to make plausible his account of capacities in terms of possibilities. Lehrer (1976). See Fischer (1979).

The neuroscience of voluntary motor movement is summarized in Moore (2011a).

132 Eng. Rep. 490 (C.P. 1837).

Holly Smith examines the conditions under which we are justified in making such negative moral evaluations, Smith (2011).

See e.g., Pillsbury (1996, p. 150) (“We judge persons according to their choices, on the assumption that they are responsible for the motivations which drive those choices. If we were not responsible for our motivations, individual responsibility would be impossible.”) See also Fletcher (1971, p. 417), for the claim that retributivism requires the law to “fathom the kind of a man” someone is in order to assess his just deserts. See also Holly Smith (2011).

Model Penal Code Section 2.02.

See Murphy (1992, pp. 22–23).

Alon Harel and Gideon Parchomovsky have made such an argument with regard to the impossibility of rank-ordering motivations. See Harel and Parchomovsky (1999, p. 513).

See Balt. & Ohio R.R. Co. v. Goodman, 275 U.S. 66, 70 (1927).

See Simons (2002, p. 259), for a similar rejection of the notion that a “free-floating incapacity or incompetence” is ever “relevant to criminal liability.”

Duff (1993, p. 364).

Moore (1997, pp. 563–564).

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code Official Draft 1962. Section 2.08 (2). In our view this is the only place where the Code gets into this forfeiture-of-defense mode of reasoning. For self-defense (section 3.04) and for balance of evils (section 3.02), the apparent forfeiture provisions are better seen as applications of the principle that earlier culpable acts causing some prohibited harm are crimes in their own right, done at an earlier time when there was no need for a defense of oneself or the prevention of a greater evil. See generally, Robinson (1985). The sort of theory involved in these latter cases is discussed in the next section.

Indeed, notice that the Model Penal Code goes further. Its threshold for the application of its ‘forfeiture doctrine’ in this section is remarkably low, for it allows negligence with regard to self-intoxication to be substituted for recklessness with regard to another’s harm!

(5) Definitions.

. . .

(b) ‘self-induced intoxication’ means intoxication caused by substances which the actor knowingly introduces into his body, the tendency of which to cause intoxication he knows or ought to know, unless he introduces them pursuant to medical advice or under such circumstances as would afford a defense to a charge of crime[.]

Thus, one who is unaware that what he is ingesting is intoxicating—but who should be aware, given the evidence available—will be held to be reckless in causing a subsequent harm to another, even if, at the time he ingested the substance, he had did not intend, did not know, did not believe that there was a risk, and had no reasonable basis for believing that there was a risk that he would find himself in a situation in which intoxication on his part would have harmful effects on another.

Model Penal Code ' 3.04 (2)(b)(i).

People v. Decina, 138 N.E.2d 799 (N.Y. 1956). The classic Decina move is discussed in Moore (1993, pp. 35–37).

Id. at 803-04.

This follows from our previously-published lengthy defense of the thesis that negligence can properly be “transferred”—or put differently, that to be negligent with regard to one type of harm is to be negligent with regard to all unjustified harms that proximately follow from that action. See Hurd and Moore (2002).

For an account that considers inadvertently-caused injuries to be blameworthy only when actors have this kind of antecedent awareness of the possibility of their later inadvertence—what he titles ‘advertence-cum-inadvertence’—see Zimmerman (1986). Andy Simester also relies on this version of the tracing strategy in part. Simester (2000, pp. 97, 99).

“It is rarely appreciated how well many handicaps can be compensated for.” Katz (1987, p. 192).

Sher (2009). As we mentioned in footnote 18, if Joseph Raz’s recently published account of negligence (Raz 2010) is not a reincarnation of Hart’s unexercised capacity view, then it can only be thought to be a less-developed version of Sher’s theory of negligence. Inasmuch as Sher’s book-length version of the account came first and is far more exhaustively articulated, we shall confine ourselves here to an exploration of his proposal.

Sher (2009, p. 88).

Id., p. 118.

Id., p. 121.

Id.

Id.

Id., p. 123.

Sher (2009, p. 130).

Id., p. 131.

Alexander and Ferzan (2009a, pp. 77–78).

To be clear, however, we do not intend here to be saying anything that contradicts our long-standing antipathy to construing rules of this sort as anything more than epistemic constructs. As we shall argue below, the most that well-known mini-maxims can be are particularly helpful sources of theoretical authority. For extended discussions of the authority that rules can possesses, see Hurd (1991, 1999). For lengthy defenses of the thesis that negligence cannot be translated into deontological “mini-maxims,” see Hurd (1994, pp. 196–98, 1996, pp. 266–268).

Commonwealth v. Welansky, 316 Mass. 383, 55 N.E.2d 902 (1944).

275 U.S. 66 (1927).

There are a number of caveats to this generalization, framed in terms of thresholds, scope limitations, and agent-relative (or strong) permissions. See generally Moore (2009, pp. 40–41, 42–76, 38), Alexander and Moore (2007). Each of these is distinct from the ordinary consequentialist justifications involved in the examples used in the text.

Pokora v. Wabash Ry., 292 U.S. 98, 104 (1934).

Regina v. Cunningham, [1957-2] Q.B. 396.

Both points are argued in Moore (2009, chapter 18).

This is a plausible construal of the facts in the well-known case of State v. Williams, 484 P.2d 1167 (Wash.Ct.App. 1971). Such is the construal also given of the facts by Husak (2011, p. 3).

Freud (1923, p. 18).

Hassin et al. (2005).

References

Alexander, L., & Ferzan, K. K. (with Morse, S.). (2009a). Crime and culpability: A theory of criminal law. Cambridge University Press.

Alexander, L., & Ferzan, K. K. (2009b). Reply. In P. H. Robinson, S. P. Garvey, & K. K. Ferzan (Eds.), Criminal law conversations (pp. 160–162). New York: Oxford University Press.

Alexander, L., & Moore, M. (2007). Deontological ethics. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. url :http://plato.stanford.edu/.

Aune, B. (1967). Hypotheticals and “can”: Another look. Analysis, 27, 191–195.

Austin, J. L. (1961). Ifs and cans. In Proceedings of the British Academy (Vol. 42, pp. 109–132). Oxford University Press.

Bergelson, V. (2009). The case of weak will and Wayward desire. Criminal Law and Philosophy, 3, 19–28.

Dennett, D. (1969). Content and consciousness. New York: Humanities Press.

Dennett, D. (1978). Beyond belief. In Intentional stance (pp. 117–212). Putney, Vt.: Bradford Books.

Duff, A. (1993). Choice, character, and criminal liability. Law and Philosophy, 12, 345–383.

Duff, A. (2009). Answering for crime: Responsibility and liability in the criminal law. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Ferzan, K. K. (2001). Opaque Recklessness. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 91, 597.

Fingarette, H. (1969). Self-deception. London: Routledge.

Fischer, J. M. (1979). Lehrer’s new move: “Can” in theory and practice. Theoria, 45, 49–62.

Fischer, J. M. (2006). Responsibility and alternative possibilities. In My way: Essays on moral responsibility (pp. 38–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fletcher, G. (1971). The theory of criminal negligence: A comparative analysis. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 119, 401–438.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the Id, The Standard Edition f the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 19, p. 18). London: Hogarth Press.

Garvey, S. P. (2006). What’s wrong with involuntary manslaughter? Texas Law Review, 85, 333–383.

Garvey, S. P. (2008). Dealing with Wayward desire. Criminal Law and Philosophy, 3, 1–17.

Garvey, S. P. (2009). Fatally circular? Not!. In P. H. Robinson, S. P. Garvey, & K. K. Ferzan (Eds.), Criminal law conversations (pp. 286–288). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gilles, D. (2000). Philosophical theories of probability. London: Routledge.

Hall, J. (1963). Negligent behavior should be excluded from penal liability. Columbia Law Review, 63, 632–644.

Harel, A., & Parchomovsky, G. (1999). On hate and equality. Yale Law Journal, 109, 507–539.

Hart, H. L. A. (1968). Negligence, mens rea and criminal responsibility. In Hart, punishment and responsibility: Essays in the philosophy of law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hassin, R., Uleman, J., & Bargh, J. (Eds.). (2005). The new unconscious. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horder, J. (1993). Criminal culpability: The possibility of a general theory. Law and Philosophy, 12, 193–215.

Hurd, H. M. (1991). Challenging authority. Yale Law Journal, 100, 1611–1677.

Hurd, H. M. (1994). What in the world is wrong? Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues, 5, 157–216.

Hurd, H. M. (1995). The levitation of liberalism. Yale Law Journal, 105, 795–824.

Hurd, H. M. (1996). The deontology of negligence. Boston University Law Review, 76, 249–272.

Hurd, H. M. (1998). Duties beyond the call of duty. Annual Review of Law and Ethics, 6, 1–39.

Hurd, H. M. (1999). Moral combat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hurd, H. M. (2002). Liberty in law. Law and Philosophy, 21, 385–465.

Hurd, H. M. (2005). Tolerating wickedness: Moral reasons for lawmakers to permit immorality. Annual Review of Law and Ethics, 167–193.

Hurd, H. M., & Moore, M. S. (2002). Negligence in the air. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 3, 333–411.

Husak, D. (2011). Negligence, belief, blame and criminal liability: The special case of forgetting. Criminal Law and Philosophy. doi:10.1007/s11572-011-9115-z.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (Vol. 2). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Johnson, E. (2006). Beyond belief. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 3, 503–522.

Kane, R. (1998). The significance of free will. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Katz, L. (1987). Bad acts and guilty minds: Conundrums of the criminal law. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

King, M. (2009). The problem with negligence. Social Theory and Practice, 35, 577–595.

Kratzer, A. (1977). What “must” and “can” must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 337–355.

Lehrer, K. (1976). “Can” in theory and practice: A possible worlds analysis. In M. Brand & J. Walton (Eds.), Action theory (pp. 241–270). Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel.

Magruder, C. (1959). Judge Macgruder: Ave Atque Vale. Harvard Law Record, 28, 6–9.

Maier, J. (2010). Ability. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2010 ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2010/entries/ability/.

Marmodoro, A. (2010). The metaphysics of powers. New York: Routledge.

Mele, A. (2003). Agents abilities. Nous, 37, 447–470.

Model Penal Code. (1962). Proposed official draft. Philadelphia: American Law Institute.

Model Penal Code Commentaries. (1985). (Part I), Official draft and revised comments. Philadelphia: American Law Institute.

Molnar, G. (2003). In S. Mumford (Ed.), Powers: A study in metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moore, G. E. (1912). Ethics, Chapter VI. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Moore, M. (1980, 1983). The nature of psychoanalytic explanation. In Psychoanalysis and contemporary thought (Vol. 3, pp. 459–543), revised and reprinted in L. Laudan (Ed.), Mind and medicine: Explanation in psychiatry and the biomedical sciences, Vol. 8 of the Pittsburgh Series in the Philosophy and the History of Science. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Moore, M. (1984). Law and psychiatry: Rethinking the relationship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, M. (1985). Causation and the excuses. California Law Review, 73, 1091–1149, reprinted as chapter 12 of Moore, Placing Blame.

Moore, M. (1988). Mind, brain, and unconscious. In P. Clark, & C. Wright (Eds.), Mind, science, and psychoanalysis. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, reprinted in Moore, Placing Blame, chapter 10.

Moore, M. (1989, 2000). Law, authority, and Razian reasons. Southern California Law Review, 62, 827–896, reprinted in Moore, Educating oneself in public: Critical essays in jurisprudence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, Ch. 5.

Moore, M. (1990). Choice, character, and excuse. Social Philosophy and Policy, 7, 28–58.

Moore, M. (1993). Act and crime: The philosophy of action and its implications for the criminal law. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Moore, M. (1997). Placing blame: A general theory of the criminal law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moore, M. (1998). Liberty and supererogation. Annual Review of Law and Ethics, 6, 111–143.

Moore, M. (2009). Causation and responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moore, M. (2011a). The challenges of contemporary neuroscience to desert-based legal institutions. Social Philosophy and Policy, 29.

Moore, M. (2011b). Causation revisited. Rutgers Law Journal.

Murphy, J. G. (1992). Bias crimes: What do haters deserve? Criminal Justice Ethics (Summer/Fall), 20–23.

Nelkin, D. (2010). Rational abilities and moral responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nowell-Smith, P. H. (1960). Ifs and cans. Theoria, 26, 85–101.

Pears, D. (1972). Ifs and cans. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 1, 369–391.

Pillsbury, S H. (1996). Crimes of indifference. Rutgers Law Review, 49, 105-218.

Rawls, J. (1993). Political liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Raz, J (1989). Facing up: A Reply. Southern California Law Review, 62, 1153–1235.

Raz, J. (2010). Responsibility and the negligence standard. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 30, 1–18.

Robinson, P. (1985). Causing the conditions of one’s own defense: A study in the limits of theory in criminal law doctrine. Virginia Law Review, 71, 1–63.

Scanlon, T. (1998). What we owe each other. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schlick, M. (1962). Problems of ethics. New York: Dover.

Sher, G. (2009). Who knew?: Responsibility without awareness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simester, A. P. (2000). Can negligence be culpable? In J. Horder (Ed.), Oxford essays in jurisprudence, Fourth Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simons, K. (1994). Culpability and retributive theory: The problem of criminal negligence. Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues, 5, 365–398.

Simons, K. (2002). Does punishment for “culpable indifference” simply punish for bad character? Examining the requisite connection between Mens Rea and Actus Reus. Buffalo Criminal Law Review, 6, 219–316.

Simons, K. (2008). Tort negligence, cost-benefit analysis, and tradeoffs: A closer look at the controversy. Loyola (Los Angeles) Law Review, 41, 1171–1224.

Simons, K. (2009). The distinction between negligence and recklessness is unstable. In P. H. Robinson, S. P. Garvey, & K. K. Ferzan (Eds.), Criminal law conversations (pp. 290–291). New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. (2004). Conflicting attitudes, moral agency, and conceptions of the self. Philosophical Topics, 32, 331–352.

Smith, M. (2004). Rational capacities. In Ethics and the a priori. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, A. (2005). Responsibility for attitudes: Activity and passivity in mental life. Ethics, 115, 236–271.

Smith, A. (2008). Control, responsibility, and moral assessment. Philosophical Studies, 138, 367–392.

Smith, H. (2011). Non-tracing cases of culpable ignorance. Criminal Law and Philosophy. doi:10.1007/s11572-011-9113-1.

Tasiltz, A. (2009). Cognitive science and contextual negligence liability. In P. H. Robinson, S. P. Garvey, & K. K. Ferzan (Eds.), Criminal law conversations (pp. 288–290). New York: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, R. (1960). I can. Philosophical Review, 69, 78–89.

Van Inwagen, P. (1975). The incompatibility of free will and determinism. Philosophical Studies, 27, 185–199.

Van Inwagen, P. (1983). An essay on free will. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Vargas, M. (2005). The trouble with tracing. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 25, 269–291.

Watson, G. (1977). Skepticism about weakness of the will. Philosophical Review, 86, 316–339.

Westen, P. (2008). Individualizing the reasonable person in criminal law. Criminal Law and Philosophy, 2, 137–162.

Williams, G. (1961). Criminal law: The general part (2nd ed.). London: Stevens and Sons.

Winters, B. (1978). Acquiring beliefs at will. Philosophy Research Archives, 4, 433–441.

Winters, B. (1979). Believing at will. Journal of Philosophy, 76, 243–256.

Wright, R. (2002a). Justice and reasonable care in negligence law. American Journal of Jurisprudence, 47, 143–196.

Wright, R. (2002b). Negligence in the courts: Introduction and commentary. Chicago-Kent Law Review, 77, 425–487.

Wright, R. (2003). Hand, Posner, and the myth of the “hand formula”. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 4, 145–274.

Zimmerman, M. J. (1986). Negligence and moral responsibility. Nous, 20, 199–218.

Zipursky, B. (2007). Sleight of hand. William and Mary Law Review, 48, 1999–2041.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written during our tenure as Fellows at the Fleming Centre for Advancement of Legal Research at the Australian National University College of Law, Canberra, Australia. Our sincere thanks to the Centre and the ANU College of Law, together with their Director and Dean, Peter Cane and Michael Cooper, respectively, for providing us with such a congenial location in which to do this work. Our thanks also go to Larry Alexander, Peter Cane, Kim Ferzan, Doug Husak, Jonathan Schaffer, Ken Simons, and Holly Smith, for providing us with helpful comments on earlier drafts of the present article. Thanks also go to the participants at the University of Chicago Law School Faculty Workshop, October, 2010, for their helpful comments. In addition to those thanked above, we would also like to thank our expert Faculty Librarian Liason, Stephanie Davidson, and our energetic research assistant, Emily Norris (J.D. 2011), for their conscientious accumulation of relevant literature and thoughtful ideas on the topic. We are grateful, as well, to the University of Illinois and to those who endowed our faculty positions for supporting our research. Thanks also go to the participants of the University of Illinois Philosophy Department Faculty Colloquium, February, 2011, for their helpful comments. We owe a special thanks, finally, to our son, Aidan Moore, both for providing us with extensive field-experience on the topic of negligence and for regaling us over recent months with countless Darwin Award stories that have repeatedly refueled our discussions of this topic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, M.S., Hurd, H.M. Punishing the Awkward, the Stupid, the Weak, and the Selfish: The Culpability of Negligence. Criminal Law, Philosophy 5, 147–198 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-011-9114-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-011-9114-0