Abstract

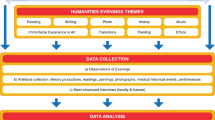

Working in healthcare can be fulfilling, meaningful, and sometimes exhausting. Creative endeavors may be one way to foster personal resilience in healthcare providers. In this article, we describe an annual arts and humanities program, the Ludwig Rounds, developed at a large academic children’s hospital. The event encourages staff to reflect on resilience by sharing their creative work and how it had an impact on their clinical careers. The multidisciplinary forum also allows staff to connect and learn about each other. We discuss the development of the program, its format and logistics, and lessons learned over the past 15 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Caring for ill or injured children can be emotionally and physically draining work. While there are many rewards—professional fulfillment in knowing the work is important, joy when one can help a child recover or improve—there is also a high risk of burnout. Medicine has made tremendous progress over the years in its ability to treat disease, yet many such advances are dependent on technology and large systems of care; multiple authors have stressed the importance of keeping our focus on individual relationships and the human values that are core to what we do amid these changes (Thibault 2019; Ludwig 2020). Creative outlets may be one way healthcare providers nurture their personal resilience and reflect on the deeply difficult human situations they encounter in their work. Having personally experienced the individual benefits of creative outlets, our group started an annual Arts and Humanities rounds open to all staff at our large, academic, quaternary-care children’s hospital.

There are other reports in the literature on using the humanities to support staff or medical trainees. Many take advantage of storytelling or narrative practices (Babal et al. 2020; Bracken et al. 2021; Childress 2017; Daryazadeh et al. 2020; East et al. 2010; Laine 2017; Olson et al. 2021; University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, n.d.; American College of Physicians 2023; Stanford Medicine 2023; Huang et al. 2021), focus on the value of creativity in medical education (Green et al. 2016; Gold Foundation, n.d.), explore the connection between music and medical practice (Weill Cornell Medicine, n.d.), or focus on visual arts training as a tool to enhance observation skills or resilience (Mukunda et al. 2019; Orr et al. 2019; Williams and Zimmermann 2020; Rx/Museum, n.d.; Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts 2020). Staff providing end-of-life care have been the focus of some programs (Ho et al. 2019). The breadth of programs described emphasizes that many clinicians find tremendous value in harnessing storytelling or creative work in their self-care or care of patients. Many reported programs encourage individuals to engage in the arts and humanities for self-care/self-renewal rather than having individuals share examples of what is already working for them. We did not find a published report describing a program exactly like the one we have created.

We started our annual sessions, ultimately named the “Ludwig Arts and Humanities Rounds,” when several organizers of the hospital’s Schwartz Center Rounds (The Schwartz Center 2023) realized we shared an interest in the arts and humanities and wanted to develop a forum for staff to share creative pursuits and highlight how such pursuits helped them foster resilience in their work. We thought an added benefit from the rounds would be that colleagues might learn something new about each other, separate from the typical work setting. The program has continued for 15 years. Herein, we describe the development and format of the program and highlight lessons learned over the years, hoping to benefit any institutions that would like to organize similar events.

Partnerships

Our institution is fortunate to have a vibrant Child Life, Education & Creative Arts Therapy Department, and members of this group contributed greatly to the planning efforts for the rounds. Music therapists helped set the scene with seating music, while Art and Music therapists often helped us identify presenters, including from among trainees in these programs.

We also made efforts to include medical trainees from the pediatric residency program and occasionally students from the affiliated School of Medicine, accommodating them by scheduling the Ludwig Rounds during the usual residency program noon conference time slot. One of the authors (SL) was the residency program director at the time that we started the program and became such a fan of the effort that he offered financial support from an endowed chair. We named the rounds after him to acknowledge his longstanding commitment to humanism in medicine.

Format

The eventual format for the rounds was a yearly, hour-long session at lunchtime, which allowed for five or six presentations. Each presenter speaks for approximately three minutes about their creative work and its impact on their resilience, followed by approximately five minutes to share their work, whether by reading, performing, showing images, or showing a video. We then ask all presenters to remain in the auditorium at the end of the hour so that attendees can talk with presenters if they wish to do so.

Over the years, we experimented with other formats. Initially, we had a panel discussion for a Question-and-Answer (Q&A) session with attendees at the end of the hour but decided to remove this component to allow time for additional presentations. We experimented with a longer evening program followed by breakout groups (including a mindfulness group, an art project, a writing group, and a drum circle). Attendance was much higher, however, at a midday session rather than an evening session. Even though the noontime weekday slot was difficult for some who would have liked to attend (e.g., staff working in the operating room), in the end, it was the most viable time for the majority who were interested.

Presenters

We identified most presenters through one-to-one discussions and word of mouth. The chief residents helped ensure that we had frequent resident participation. Emails to large distribution lists only rarely identified interested presenters. We promoted the rounds by email, announcements in newsletters, signage outside the rounds on the day they occurred, and notification of institutional leaders about the event.

We rarely had significantly more staff interested in participating than we could accommodate in any given year. We kept a running list of those who were interested but whose schedules did not allow participation, and we approached them first the following year. Each presenter met with a planning committee member beforehand to make sure the purpose of the session was understood, go over the format, and ensure that inappropriate materials or confidential patient information would not be shared. If identifying information was shared, we asked for patient/family permission.

Presenters have shared a large variety of creativity/activities (Table 1). For each session, we tried to vary the type of presentations to avoid having all music or all reading, for instance. We attempted to avoid having repeat presenters, although on one occasion, a trainee sang one year and shared poetry in a later year, and we had another repeat presenter (a planning committee member) when there were two last-minute cancellations.

Over the years, we had presenters from a variety of professional backgrounds (Table 2). We learned the importance of having a multidisciplinary planning committee—noticing, for instance, that we were far more likely to have nurse presenters in years when we had a nurse on the planning committee. Including stakeholders from many disciplines and areas of the hospital in planning is, therefore, key.

Creating a safe space for staff

In the planning stages, we intentionally chose to protect the space for staff only rather than including patients or families in the audience. We felt that protecting the space in this way would allow staff to share vulnerability in a way they might not feel comfortable doing otherwise. Our institution employs a handful of patient family members to advise and contribute to institutional committees—the “family faculty,” who were welcome to attend.

We also made sure to emphasize to all attendees at the beginning of each session that the goal of presentations was not a talent display. We encouraged attendees who wanted to talk with presenters afterward to share how they felt rather than praise the “performance.” We emphasized the focus on resilience rather than talent to encourage attendees new to creative endeavors to consider using such outlets in their self-care. We also wanted to acknowledge specifically that participation in the arts and humanities can offer benefits no matter what the skill level of the work (Gharib 2022). As examples of how resilience was discussed, our juggler talked about how getting outdoors in the park to juggle helped him get through residency, a midwife discussed how her knitting creations led to connections with patients and colleagues, and a trainee discussed how singing felt like a way to be his true self.

Pandemic pivot to a virtual format

The COVID-19 pandemic required significant pivots in our event planning due to planning committee bandwidth and the need for physical distancing. We often had more than 100 attendees at pre-pandemic gatherings. While we were slightly delayed in our “annual” event schedule, we hosted two virtual Arts and Humanities rounds. From this experience, we learned that music can be difficult to share if background noise cancellation features are in place. Seeking appropriate technical support to choose the best virtual presentation format was helpful, and pre-recording videos of musical performances worked better. Having a chat or Q&A function available was also useful to allow attendees to add thoughts since it is more difficult for the spontaneous, individual conversations that had often occurred after the session to happen.

Related efforts

The Ludwig Rounds are not the only forum to use the arts and humanities for staff support at our institution. There have been several discipline-specific groups using the arts and humanities to build resilience. These include a reflective writing (narrative medicine) evening group, and several frequent contributors have been Ludwig Rounds presenters. A group of residents and faculty also started a literary journal, now in its second year of publication. In addition, there are several musical groups formed from relationships that started at work, from classical to jazz to a Beatles cover band. One Ludwig Rounds attendee reported being so inspired by seeing presenters who had maintained their musical interests despite having busy clinical lives that she reinvigorated her musical interest that had been put aside for medicine—eventually performing with a group that played at national conferences and local venues.

Benefits and challenges

Challenges we identified in organizing the Ludwig Rounds included the time commitment needed from the organizing committee, difficulty in choosing a time of day that would work for all interested, and challenges with identifying consistent ways to increase awareness. In addition, finding a conference/presentation space where various forms of art could be shared required long-term planning. Providing food at a noon session (when in person) helped attendees be present for the full hour. Food was the main cost of the program, with a budget of a few hundred dollars. Benefits reported by staff who attended have included the importance of having a “refresher” on resilience during busy clinical work, an improvement in their ability to connect with colleagues by learning more about them, and an appreciation for the examples of how others use the arts and humanities to foster resilience. This report does not include a quantitative assessment of the value of the sessions—conducting such an analysis would be an important future study.

Reinforcing connections between the arts and resilience was challenging at times. While some of the more discursive art forms (i.e., writing, poetry) occasionally made references to clinical experiences, other art forms appeared to foster resilience in a more indirect way, potentially by offering the clinician some separation from the clinical environment. Although presenters were encouraged to articulate insights into their creative process and connections with their work in healthcare, many focused primarily on presentation and discussion of their creative outlet. Table 3 lists important take-home points.

Conclusions

A forum for healthcare providers and other hospital staff to share personal experiences using the arts and humanities to foster resilience has become a long-standing and valued addition to the programming offered at an academic children’s hospital. These rounds have been a well-attended and positively evaluated experience for 15 years. We feel that the organizers, presenters, and attendees all benefitted from the shared examples of resilience developed within creative endeavors. Such efforts have become “cup-fillers” for many of us. We hope that other institutions would be interested in developing similar programs.

References

American College of Physicians. 2023. “Annals Story Slam.” Annals of Internal Medicine, Web Exclusives. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.acpjournals.org/topic/web-exclusives/annals-story-slam

Babal, Jessica C., Sarah A. Webber, and Emily Ruedinger. 2020. “First, Do No Harm: Lessons Learned from a Storytelling Event for Pediatric Residents During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Academic Pediatrics 20 (6): 761–62.

Bracken, Rachel Conrad, Ajay Major, Aleena Paul, and Kirsten Ostherr. 2021. “Reflective Writing about Near-Peer Blogs: A Novel Method for Introducing the Medical Humanities in Premedical Education.” Journal of Medical Humanities 4:535–69.

Childress, Marcia Day. 2017. “From Doctors’ Stories to Doctors’ Stories, and Back Again.” AMA Journal of Ethics 19 (3): 272–80.

Daryazadeh, Saeideh, Payman Adibi, Nikoo Yamani, and Roya Mollabashi. 2020. “Impact of Narrative Medicine Program on Improving Reflective Capacity and Empathy of Medical Students in Iran.” Journal of Education Evaluation for Health Professionals 17:3.

East, Leah, Debra Jackson, Louise O’Brien, and Kathleen Peters. 2010. “Storytelling: An Approach that Can Help to Develop Resilience.” Nurse Researcher 17 (3): 17–26.

Gharib, Malaka. 2022. “Making Art Is Good for Your Health. Here’s How to Start a Habit.” National Public Radio, December 21, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2019/12/30/792439555/making-art-is-good-for-your-health-heres-how-to-start-a-habit

Gold Foundation. n.d. “2017 National Conference on Humanism.” Programs, Gold Humanism Honor Society (GHHS). Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.gold-foundation.org/programs/ghhs/ghhs-2017-national-conference-on-humanism/

Green, Michael J., Kimberly Myers, Katie Watson, MK Czerwiec, Dan Shapiro, and Stephanie Draus. 2016. “Creativity in Medical Education: The Value of Having Medical Students Make Stuff.” Journal of Medical Humanities 37 (4): 475–83.

Ho, Andy Hau Yan, Geraldine Tan-Ho, Thuy Anh Ngo, et al. 2019. “A Novel Mindful-Compassion Art Therapy (MCAT) for Reducing Burnout and Promoting Resilience for End-of-Life Care Professionals: A Waitlist RCT Protocol.” Trials 20 (1): 406.

Huang, Chien-Da, Chang-Chyi Jenq, Kuo-Chen Liao, Shu-Chung Lii, Chi-Hsien Huang, and Stai-Yu Wang. 2021. “How Does Narrative Medicine Impact Medical Trainees’ Learning of Professionalism? A Qualitative Study.” BMC Medical Education 21 (1): 391.

Laine, Christine. 2017. “Do Stories Deserve a Place in Medical Journals?” Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association 128: 147–56.

Ludwig, Stephen. 2020. “Professionalism.” Pediatrics in Review 41 (5): 217–23.

Mukunda N, Moghbeli N, Rizzo A, Niepold S, Bassett B, DeLisser HM. 2019. Visual art instruction in medical education: a narrative review. Med Educ Online 24(1):1558657. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2018.1558657

Olson, Maren E., M. Lynne Smith, Alexandra Muhar A, Trisha K. Paul, and Bernard E. Trappey. 2021. “The Strength of Our Stories: A Qualitative Analysis of a Multi-Institutional GME Storytelling Event.” Medical Education Online 26 (1): 1929798.

Orr, Andrew R., Nazanin Moghbeli, Amanda Swain, et al. 2019. “The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) Workshop: A Partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art.” Advances in Medical Education and Practice 10: 361–69.

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. 2020. “Art & Medicine Programs.” Programs for Adults. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.pafa.org/museum/education/adults/art-medicine-programs

Rx/Museum. n.d. “About Us.” Accessed June 24, 2022. https://rxmuseum.org/partners

Stanford Medicine. 2023. “Medicine & the Muse Program.” Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://med.stanford.edu/medicineandthemuse/events.html

The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare. 2023. “Schwartz Rounds and Membership.” Programs. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.theschwartzcenter.org/programs/schwartz-rounds/

Thibault, George E. 2019. “Humanism in Medicine: What Does It Mean and Why Is It More Important Than Ever?” Academic Medicine 94 (8): 1074–77.

University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. n.d. “Nursing Story Slam.” Innovation. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.nursing.upenn.edu/innovation/nursing-story-slam/

Weil Cornell Medicine. n.d. “Music and Medicine.” Accessed May 18, 2023. https://music.weill.cornell.edu

Williams, Ray, and Corinne Zimmermann. 2020. “Twelve Tips for Starting a Collaboration with an Art Museum.” Journal of Medical Humanities 41 (4): 597–601.

Funding

Dr. Morrison’s time is supported by the Justin Michael Ingerman Endowed Chair in Palliative Care. Dr. Ludwig’s time is supported by the John H. and Hortense Cassell Jensen Endowed Chair in Pediatric Development and Teaching.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No authors have competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Morrison, W., Steinmiller, E., Lizza, S. et al. Harnessing the Humanities to Foster Staff Resilience: An Annual Arts and Humanities Rounds at a Children’s Hospital. J Med Humanit 45, 113–119 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-023-09804-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-023-09804-2