Abstract

In this paper I argue that the use of social nudges, policy interventions to induce voluntary cooperation in social dilemma situations, can be defended against two ethical objections which I call objections from coherence and autonomy. Specifically I argue that the kind of preference change caused by social nudges is not a threat to agents’ coherent preference structure, and that there is a way in which social nudges influence behavior while respecting agents’ capacity to reason. I base my arguments on two mechanistic explanations of social nudges; the expectation-based and frame-based accounts. As a concrete example of social nudges I choose the “Don’t Mess With Texas” anti-littering campaign and discuss in some detail how it worked.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Until Section 4.2 where it becomes relevant I defer the discussion of the distinction between the responsiveness-to-reasons view and the responsiveness-to-reasoning view, which is that the former is strongly externalist (i.e. reasons should correspond to external reality) while the latter is weakly so (i.e. reasoning should respect certain objective norms, but it can accommodate false beliefs) (Buss 2014).

These examples are mine.

They might also have exceptional beliefs that their lives or the world will end before they start to suffer from their dietary choice.

Bovens (2009) doesn’t state this explicitly (see footnote 8 on page 214), so this is my reconstruction.

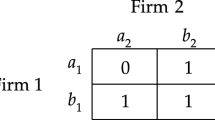

Here I am interpreting the social dilemma as a dilemma for individuals, as well as for social planners. Some game theorists adopt an alternative interpretation according to which individuals do not face any dilemma as they simply choose dominant strategies based on their preferences. On this reading a C-choice is against their self-interest by definition, although such a view is not common in social sciences.

This number is Schelling’s kSchelling (1978, ch.7).

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for giving me the courage to say this.

Thaler and Sunstein (2008) refer to the “spot-light effect”, which makes us believe that others pay more attention to us and our behavior than they really do when we become aware that we look or behave differently from others. Although this effect sometimes creates false beliefs—e.g., that the audience of my presentation scorn my shabby jacket when no one actually cares—this doesn’t seem to explain the case of “Don’t Mess With Texas” because in a typical Texan road there aren’t many people around you.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for making me realize this point clearly.

Bacharach et al. (2006, ch.3) speculate on the evolutionary mechanism of the human propensity to adopt a we-framing in certain coordination and cooperation problems.

Note however that Bacharach’s view that framing is neither rational nor irrational is not widely accepted. First of all, it seems to be in tension with his interdependence hypothesis and his model of circumspect team reasoning that explicitly weighs the risk of others not adopting a we-frame. Another prominent team reasoning theorist Sugden (1993) also suggests that for a player to adopt a we-frame, she needs assurance or common reason to believe that enough others do the same. More generally, many emotion researchers emphasize that the way we construe (or frame) a decision situation is motivated by our salient concerns, i.e., ‘the attachments and interests from which many of our desires and aversions derive.’ Roberts (2003, 142).

Except for the semantic association between the slogan (“mess with Texas”) and littering (“mess up Texas”).

References

Bacharach, M., N. Gold, and R. Sugden. 2006. Beyond individual choice: teams and frames in game theory, Princeton. N. J.: Princeton University Press.

Bicchieri, C. 2006. The Grammar of Society. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Bovens, L. 1992. Sour grapes and character planning. The Journal of Philosophy, 89(2): 57–78.

Bovens, L. 2009. The ethics of nudge. In Preference Change: Approaches from Philosophy Economics and Psychology, chapter 10, eds. T. Grüne-Yanoff and S. O. Hansson, 207–219. Springer, New York.

Buss, S. 2014. Personal autonomy. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 ed.), ed. E. N. Zalta. Stanford University.

Camerer, C., S. Issacharoff, G. Loewenstein, T. O’Donoghue, and M. Rabin. 2003. Regulation for conservatives: Behavioral economics and the case for ‘asymmetric paternalism’. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 151(3): 1211–1254.

Dworkin, G. 2013. Defining paternalism. In Paternalism: theory and practice, Chapter 1, eds. C. Coons and M. Weber, 25–55. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Elster, J. 1983. Sour Grapes: Cambridge University Press.

Gächter, S., and C. Thöni. 2007. Rationality and commitment in voluntary cooperation: Insights from experimental economics. In Rationality and Commitment, Chapter 8, eds. F. Peter and H. B. Schmid, 175–208. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Grüne-Yanoff, T. 2012. Old wine in new casks: libertarian paternalism still violates liberal principles. Social Choice and Welfare, 38: 635–645.

Grüne-Yanoff, T. (2014, Februrary). Why behavioural policy needs mechanistic evidence. unpublished manuscript.

Guala, F., L. Mittone, and M. Ploner. 2013. Group membership, team preferences, and expectations. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 86: 183–190.

Hausman, D. M., and B. Welch. 2010. Debate: To nudge or not to nudge. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 18(1): 123–136.

Heilmann, C. 2014. Success conditions for nudges: a methodological critique of libertarian paternalism. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 4: 75–94.

Loewenstein, G., and E. Haisley. 2008. The economist as therapist: methodological ramifications of ’light’ paternalism. In The Foundations of Positive and Normative Economics: A Handbook, The Handbooks in Economic Methodologies, Chapter 9, eds. A. Caplin and A. Schotter, 210–245. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Roberts, R. C. 2003. Emotions: an essay in aid of moral psychology. Cambridge. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Schelling, T. C. 1978. Micromotives and Macrobehavior, W.W. Norton & Co, New York.

Shafir, E. 2013. The behavioral foundations of public policy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Smerilli, A. 2012. We-thinking and vacillation between frames: filling a gap in bacharach’s theory. Theory and Decision 73(4): 539–560.

Sugden, R. 1993. Thinking as a team: Towards an explanation of nonselfish behavior. Social Philosophy and Policy, 1: 69–89.

Sugden, R. 2009. On nudging: A review of nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 16(3): 365–373.

Thaler, R. H., and C. R. Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1986. Rational choice and the framing of decisions. The Journal of Business, 59(4): S251—S278.

Acknowledgments

The idea of this paper was born in Manchester where I worked as Sustainable Consumption Institute postdoc for the project Motivations of Indifference led by late Peter Goldie. I regret that I cannot show this to Peter. I thank Michael Scott for his support during the project. The paper developed thanks to the comments I received in Manchester, Rotterdam, Trento, Helsinki, Oviedo and Madrid. I am grateful to the University of Oviedo for the research visit grant, and Armando Menéndez Viso for his hospitality. I also thank David Teira for inviting me to UNED, Madrid. Two anonymous reviewers and the editors helped me improve the paper substantially, for which I am grateful. Finally I thank Miles MacLeod for a “buddy” language check. All the remaining mistakes are mine.

Compliance with ethical standards

This research was initiated while I was funded by Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester (2009-2010); I am currently funded by TINT/Academy of Finland Centre of Excellence in the Philosophy of the Social Sciences, University of Helsinki. The paper also benefited from my research visit to the University of Oviedo (Nov. 2014) funded by the same university. I believe there is no conflict of interest involved in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nagatsu, M. Social Nudges: Their Mechanisms and Justification. Rev.Phil.Psych. 6, 481–494 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0245-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0245-4