Abstract

Although the literature on the issue of pluralism within the philosophy of science is very extensive, this paper focuses on the metaphysical causal pluralism that emerges from the new mechanistic discussion on causality. The main aim is to situate the new mechanistic views on causation within the account of varieties of causal pluralism framed by Psillos (2009). Paying attention to his taxonomy of metaphysical views on causation (i.e., the straightjacket view, the functional view, the two-concept view, the agnostic view and the atheist view) will help clarify differences in opinion and, at the same time, make it possible to elucidate the main metaphysical theses present within the new mechanistic debate. Special attention is given to S. Glennan’s theory of causation, since it is unique in offering an overall metaphysical view of the issue. It is also argued that mechanists are not “atheists” on causation: while all of them are causal realists, most mechanists are “agnostic” on causation, with a few exceptions such as S. Glennan, P. Machamer and J. Bogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the current philosophical literature dedicated to the issue of causality, there is a debate on the diversity of causal concepts (Campaner & Galavotti, 2007; Cartwright, 2004; Godfrey-Smith, 2009; Hall, 2004; Hitchcock, 2007). This paper, however, is not structured around a complete taxonomy of causal pluralism as such and instead focuses on the metaphysical causal pluralism that emerges from the new mechanistic discussion on causality. The reason for this choice of the new mechanical philosophy (NMP) is that the NMP is one of the dominant approaches within the current philosophy of science and has produced extensive literature not only on mechanisms and mechanistic explanation, but also on the problem of causation. The intersection of the attempt to understand the nature of mechanisms and the focus on explanatory practices across different scientific fields has brought a renewal of causal explanations within the mechanistic framework.

Although the literature on the issue of pluralism within the philosophy of science is very extensive (e.g., Kellert et al., 2006; Mitchell, 2003), I will focus on the character of that pluralism within the NMP. More specifically, my main aim is to situate the new mechanistic views on causation within the account of varieties of causal pluralism framed by Psillos (2009). Paying attention to Psillos’s taxonomy of metaphysical views on causation will help clarify differences in opinion and, at the same time, make it possible to elucidate the main metaphysical theses present within the NMP debate. In the first section of the paper, I offer a brief introduction on why causation has been put at the core of the new mechanistic agenda. This section may be particularly insightful as a brief historical and theoretical survey for those who are not friends of the NMP. Here, I also raise the issue of the plurality of causal views, arguing that each approach gives an important insight into the philosophical discussion about causality. Then, I discuss S. Glennan’s theory of causation, which is unique in offering an overall metaphysical view of the issue. In the third section, I focus on explicating the important similarities and differences between the previously discussed approaches and interpret them in the grid of metaphysical causal pluralism. Moreover, I taxonomize the space of mechanistic positions on causation, following closely Psillos’s distinction between different views on causal pluralism, that is, the straightjacket view, the functional view, the two-concept view, the agnostic view and the atheist view. In the fourth section, I explain in what sense mechanistic pluralism should not be considered trivial. Finally, I conclude by arguing that mechanists are causal realists and that, with a few exceptions, they are agnostic on the nature of causation.

2 Causation Revisited

One of the main reasons why the philosophical debate on causation has been reignited is probably the fact that causal explanation was not successfully absorbed by C. Hempel’s account of explanation (Hempel, 1965, pp. 350–352). Contrary to the Hempelian “received view,” mechanistic philosophers focused their attention on different ways of describing natural phenomena and on the structure of explanation in science. In fact, the mechanistic literature of the 1993–2000 period began with the observation that the standard philosophy of science did not say a word about mechanisms. In their seminal work, Machamer, Darden and Craver (2000, p. 3) defined mechanisms as “entities and activities organized such that they are productive of regular changes from start or set-up to finish or termination conditions.” Even if mechanists disagreed with one another on how to precisely define mechanisms, the common denominator of their approaches is the conviction that the study of mechanisms is strictly interwoven with mechanistic explanation, which involves isolating a set of phenomena (i.e., an entity or system that is engaged in a certain activity) and positing a mechanism that is capable of producing those phenomena (Illari & Williamson, 2011, 2012). The basic account of mechanistic explanation differs from the aforementioned Hempelian deductive-nomological account. While there is an extensive amount of literature on the problem of mechanisms, mechanistic models and mechanistic explanation, the thirty years of research into mechanisms can be expressed in six theses that unpack the “core results” of the mechanistic agenda (Glennan et al., 2022):

-

1.

the minimal mechanism thesis: a mechanism for a phenomenon consists of entities (or parts) whose activities and interactions are organized so as to be responsible for the phenomenon;

-

2.

the representation thesis: mechanisms are discovered, described and explained through the construction of partial, abstract, idealized and plural models;

-

3.

the ubiquity thesis: mechanistic explanations are commonly present across the empirical sciences;

-

4.

the explanatory pluralism thesis: mechanistic explanations are a subset of the broader category of scientific explanations;

-

5.

the discovery pluralism thesis: the diversity of kinds of mechanisms requires the diversity of tools and strategies for mechanism discovery; and.

-

6.

the fruitfulness thesis: the mechanistic philosophy provides insights that can be applied to reasoning problems in science, technology and evidence-based policy.

A brief look at these theses is enough to see that it is difficult to pin down the NMP because it embraces numerous and very complex problems that stem from both the philosophy of science and the individual sciences. Still, the minimal mechanism thesis reveals an important point of consensus among mechanists on how to understand the nature of mechanisms, thus providing a good starting point for my further analysis. As Glennan et al. (2022) rightly note, one of the virtues of this definition

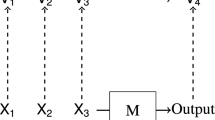

is that it allows mechanisms to have both a causal and a part-whole dimension. It is a point of consensus among New Mechanists that mechanisms generally can have two dimensions (Craver & Tabery, 2019; Glennan, 2017). In their horizontal (causal dimension), mechanisms move from start points to end points, or maintain states over periods of time. . In their vertical or part-whole dimension, the activity of some composite entity is made up of the activities of its component parts. . The definition of minimal mechanism characterizes the relation between a mechanism and its phenomenon as one of responsibility, allowing us to consider both causal/processual cases, where the output of a mechanism depends causally on its inputs, and constitutive cases where the activity of a mechanism as a whole depends upon the activities of its parts. The proper understanding of the relationship between these two dimensions is far from settled—but minimal mechanism provides a framework for organizing these debates. (pp. 145–146)

The problem of causation lies at the heart of the NMP. Mechanisms are considered as being two-dimensional: horizontal-causal and vertical-constitutive.

I would like to emphasize from the beginning that none of the new mechanists holds the view that causation is merely a mental construct. Although causation is a mind-independent phenomenon, that is, it corresponds to something real in the world, new mechanists agree that causal discovery is a very complex issue (Pearl & McKenzie, 2018). In fact, mechanists emphasize (theses 2, 4, 5) that causal relations in the world are not merely given to us and that their study in fact requires the employment of appropriate models, explanatory frameworks and heuristics for mechanism discovery. I will not address the details of the debate over the variety of “conceptions of explanation,” which are understood as views about what explanations are, and “accounts of explanation,” which are conceived of as views about how explanations work (Bokulich, 2016, p. 263; Wright & van Eck, 2018; blinded for peer review). Although the analysis of the main tenets of the so-called mechanistic explanation and the feasibility of this type of explanation in various disciplinary contexts is a crucial issue (see e.g., blinded for peer review), my motivation is more limited in the sense of providing the resources that will guide philosophical research on the mechanistic pluralism of causal views. If one agrees that causal realism can be described by two basic assumptions, namely that causation is something that occurs in an external reality as opposed to something that is merely subjective and that it involves some sort of necessity with respect to the connection between causes and effects (Chakravartty, 2005), then it can be said that all mechanists are causal realists. Thus, I will label mechanists’ position on causation as “metaphysical causal realism.”

While all new mechanists take for granted causal realism of some sort, there are at least two distinct attitudes among them with regard to causation. One group—for example, L. Darden, C. Craver, W. Bechtel and their collaborators—have been more concerned with epistemic/methodological issues, helping themselves to whatever causal theory and methods have been useful. It seems that this group fits best within the “agnostic pluralism” that will be defined later. Mechanisms, if viewed from certain epistemic or methodological perspectives, can be classified by the kinds of activities/operations/interactions in which their parts engage (Craver, 2007, pp. 5–6). While W. Bechtel and R. Richardson (2010) focused on the idea of decomposition and localization as fallible heuristics of mechanism discovery, C. Craver and L. Darden (2013) have offered their own account of discovery heuristics for mechanisms.

Moreover, one of the crucial influences of Woodward’s counterfactual account (Woodward, 2002) on the mechanistic causal debate can be noted in the case of Craver’s account of constitutive relevance (Craver, 2007, pp. 139–160).Footnote 1 The latter concerns the mechanistic conundrum of how the activities of mechanistic parts make a difference to the activities of whole mechanisms. On the one hand, this account tries to deal with the problem of causal relevance (i.e., how causes make a difference to their effect) in the context of mechanistic organization; on the other hand, it tries to offer an essential method for identifying the working constituents of a mechanism. Whether Craver’s account is successful in solving these problems has been the subject of much ongoing discussion (Leuridan, 2012; Romero, 2015; Baumgartner & Gebharter, 2016; Harinen, 2018). What is important for our aims is that Craver considers his mutual manipulability account as an epistemic criterion rather than a metaphysical view, inspired by certain kinds of neuroscientific interlevel experiments (Craver et al., 2021). It seems, therefore, that “methodologically guided” mechanists believe that causes make a difference (at least most of the time), but none of them argues that this is what is metaphysically essential about them.

The other group—for example, S. Glennan, P. Machamer and J. Bogen—have spent more time attempting to develop an anti-Humean metaphysical view about the nature of causation. In fact, most of new mechanists share a dissatisfaction with the Humean regularity view of causation, although each of them responds to Hume in a different way (Matthews & Tabery, 2018). In his early work, Glennan (1996) attempted to identify the necessary connection between cause and effect as sought by Hume, arguing that mechanisms provide the necessary connections between causes and effects. Referring to the view expressed by E. Ansombe (1993), Bogen (2008) dismisses Hume’s challenge, arguing that the whole question of the observability or non-observability of the causal relation is a red herring. Bogen criticizes the Humean generalist account of causation, pointing out that the idea that we cannot form concepts directly from sensual experience is hopelessly out of date. Although we can observe singular causal relations, the concept of causation is a theoretical term. At the same time, Bogen does not neglect the epistemic value of regularities or generalizations, arguing instead that causes should not be reduced to regularities. Having analyzed the two distinct attitudes towards causation present among new mechanists, the first one being more concerned with epistemic/methodological issues and the second one with metaphysical issues, we can now concentrate on other attempts to pin down the new mechanistic view on causation.

Another attempt to classify new mechanistic positions on mechanisms and their causal role was to provide a distinction between “monist” and “dualist” views (Schiemann, 2019, pp. 39–43). The main representative of the former would be Glennan, whereas the latter would be represented by Machamer, Darden and Craver. In the monist case, one can speak of entities with capacities/dispositions to act or of interactions of entities. While monists (or substantivalists) focus their attention on entities, dualists concentrate on activities. Kaiser (2018, pp. 120–124) has come to a similar conclusion on the difference between the two positions. S. Psillos and S. Ioannidis (2019) argue that Glennan’s account suggests the sort of a substantive metaphysical view that seems to be at least broadly neo-Aristotelian, but recent developments in the NMP suggest that this is not a fair metaphysical characterization of mechanistic accounts. In fact, all the well-known definitions of mechanisms invoke some kind of dualism (entities and activities, parts and interactions, parts and operations, etc.), and this is recognized as a common element of the minimal mechanism thesis. Let us expand on this issue now.

It is true that the Anscombian view was already introduced in the definition of mechanisms offered by Machamer, Darden and Craver (2000, p. 6). Briefly put, this view focuses on the presence of highly general causal expressions in our daily talk and on the existence of causation in the world that answers to this talk. Machamer (2004) and Bogen (2008) are probably most indebted to such a view, and they accordingly emphasize that the most important fact about activities is that there are a lot of them. Since there is more than one thing in the world that is “causing” or “acting,” there are many kinds of activities. Craver also embraces the pluralism of activities, but he is not a primitivist in an Anscombian sense like Machamer or Bogen are. He formulates an epistemic and difference-making account of constitutive relevance, as mentioned before, where activities are mechanism-dependent. In a departure from his initial formulations, S. Glennan embraces activities talk, too, and argues that most activities and entities are mechanism-dependent (Glennan, 2017, pp. 31, 34). In the light of the recent literature, it seems that both monists and dualists, if one wants to use this distinction, distance themselves from the Anscombian view, or, as Psillos calls it, Wittgensteinian pluralism (Psillos, 2009, pp. 144–149). New mechanists, with the exception of Machamer and Bogen, emphasize the mechanism-dependence of activities or entities instead. Thus, the concept of causal mechanism—rather than that of activity—proves to be the basic metaphysical category upon which the mechanistic philosophical edifice is founded.

Finally, if one analyzes the issue of causality within the NMP, it should be acknowledged that new mechanists are much indebted to W. Salmon’s mechanistic account (Campaner, 2013). The key concept of Salmon’s theory is the notion of causal process, whereby “a process that transmits its own structure is capable of propagating a causal influence from one space-time locale to another” (Salmon, 1984, p. 155). Another key concept is causal production, which takes place whenever there is a causal interaction, and the changes in the structure of processes continue to be propagated until another interaction takes place. Salmon’s focus on the causal process, production and interaction brought with itself a greater emphasis within the NMP on the productive spatiotemporal continuity (understood as the transmission of matter/energy from cause to effect via a causal process), the parts of mechanisms that produce a given behavior by interacting with each other, and the causal mechanisms that make up the complex nexus of the worldly causal structure. In addition to the fact that Machamer, Darden and Craver’s definition of mechanism is processual, Glennan has recently developed accounts of mechanistic processes (2017, pp. 170–184), and Craver et al. (2021, pp. 8825–8827) have agreed that mechanisms are at their core processual. This means that the processual approach is being deeply embraced by that based on the mechanism-dependence of activities and entities.

In light of the above, the metaphysical causal pluralism can be described by a variety of notions such as activities, entities, complex causal systems, mechanism-dependence, processes, causal and constitutive relations, etc. Leaving things at this stage could mean that such a pluralism becomes like “the muddle.” In order to avoid this, we need to first disentangle the main aspects of Glennan’s theory of causation and then outline the taxonomy of the new mechanistic metaphysical causal pluralism.

3 Glennan’s Mechanistic Theory of Causation

The philosophical positions of various mechanists have developed and sometimes shifted over the last thirty years. This is perhaps most obvious in the case of S. Glennan and C. Craver. Since the former has been the only mechanist to offer an overall metaphysical view of causation, let us focus on the main aspects of his approach (Glennan, 1996, 2002, 2010, 2017).

One can note a big difference between the ideas described in Glennan’s seminal paper from 1996 and the mature and most elaborated views expressed in his 2017 book. While in the 1996 paper (p. 52), Glennan explained that a mechanism is a complex system which produces a behavior via the interaction of a number of parts according to direct laws, in the 2002 paper (p. S344), he wrote that those interactions are characterized by direct, invariant, change-relating generalizations. His 1996 attempt to characterize interactions between parts of mechanisms in terms of laws has been criticized as being misleading and evoking the nomothetic conception of explanation, which is why he has opted for a characterization of interactions in terms of Woodward’s invariant change-relating generalizations. Although it may seem that in his 2002 paper, he intended to define causal relations primarily in manipulationist terms, he has in fact firmly and repeatedly stated since the beginning of his work that facts about mechanisms are basic ones. I will now unpack the latter claim.

In what follows, I will reconstruct his mechanistic theory of causation by formulating six main theses:

-

1.

Mechanism (M): “A mechanism for a phenomenon consists of entities (or parts) whose activities and interactions are organized so as to be responsible for the phenomenon” (2017, p. 17).

-

2.

Fundamental Mechanism (FM): A fundamental (or basic) mechanism is “a set of entities engaging in activities and interactions that does not depend upon other mechanisms” (2017, p. 185).

-

3.

Compound mechanisms (CoM): Mechanisms other than FMs are mechanism-dependent, that is, they depend upon other mechanisms. Following Glennan, I will call them compound mechanisms (2017, p. 185).

-

4.

Mechanistic Causation (MC): “A statement of the form ‘Event c causes event e’ will be true just in case there exists a mechanism by which c contributes to the production of e” (2017, p. 156). Another formulation is: “One event causes another when there exists a mechanism by which the causing event c contributes to the production of the effect event e” (2017, p. 179).

-

5.

Event (E): “An event is just one or more entities engaging in an activity or interaction” (2017, p. 177).

-

6.

Causal structure of the world (CSW): “The totality of mechanisms—including their (generally mechanism-dependent) parts, activities, and interactions—constitutes ‘the causal structure of the world’” (2017, p. 148).

Let us briefly comment on the above theses. First of all, Glennan’s formulation of MC deeply resembles J. Williamson’s definition of the mechanistic theory of causality, which states that there is a metaphysical connection such that “two events are causally connected if and only if they are connected by an underlying physical mechanism of the appropriate sort” (Williamson, 2011, p. 421). Furthermore, Glennan describes causal relationships by using essentially two terms: causal production and causal relevance (Glennan, 2017, pp. 170–210). The former term, referring to W. Salmon’s theory, means that causal productivity involves the transmission of something from cause to effect via a causal process. Although Glennan points out that the production relation can be divided into three types, that is, constitutive, precipitating and chained (Glennan, 2017, pp. 179–184), for the purposes of this paper, I will reduce all of them to one notion of causal relation. According to Glennan, causal relevance claims are comparative claims about actual or possible productive causal mechanisms. These types of statements describe the causal situation, that is, those properties of the entities, activities and interactions that make a difference to the occurrence of an event. Although for Glennan, production and relevance are two different concepts of cause, it seems that production is the fundamental one, namely that “there are many kinds of causal production corresponding to the many ways that different activities and interactions can produce change” (Glennan, 2017, p. 155). Production, conceived of as a synonym of causation, is grounded in productive mechanisms, since the productive capacity of mechanisms arises from the organized causal powers of their components. I would state that for Glennan, mechanisms are productive causal processes. Furthermore, I would suggest a reduction of the different aspects of causal claims exposed by Glennan to the general notion of causal relation expressed in the following statement: “that c produces e on the ground of M under certain circumstances.” More formally, it could be expressed in the following way:

-

\({C}_{x}\left(c,e\right)\), that is, the relation between c and e holds on the ground of x; and.

-

\({C}_{x}\left(c,e\right)\to M\left(x\right)\), that is, if c causally produces e on the ground of x, then x is a mechanism (M).

Probably the main virtue of Glennan’s current account is the fact that it embraces accounts of causal production (being clearly indebted to Anscombe’s and Salmon’s views in that respect) and accounts of causal relevance (such as Woodward’s), leaving mechanisms at the heart of his philosophical project. In the case of Salmon, Glennan not only points out that Salmon’s approach shares many features with the NMP approach (Glennan, 2017, p. 7), but also admits that he himself has been deeply inspired by Salmon’s philosophy of causation. For instance, Chaps. 7 and 8 (Glennan, 2017, pp. 170–238) recycle crucial notions taken from Salmon, such as production and interaction, causal relevance, the distinction between constitutive and etiological aspects of causal explanations, and the usefulness of counterfactuals if interpreted experimentally. Although further nuances of Salmon’s view on causal explanation are not the object of my examination here, it is also important to emphasize that Glennan’s CSW thesis evokes deeply metaphysical tones from Salmon (1984, pp. 178–183).

As noted, the truth conditions for singular causal claims are settled by the existence of mechanisms (Glennan, 2017, p. 156). This shows important changes in Glennan’s view of causation. He conceives of productive mechanisms as the truth-makers of causal claims. His account may be defined as a singularist one, since it focuses on particular mechanisms that link particular causes and effects: “Causation requires mechanisms, and mechanisms are spatiotemporally localized particulars” (Glennan, 2017, p. 227). In another place, he notes that

singular causal relations can obtain even if they are not instances of causal regularities or laws, and what makes causal generalizations true, when they are true, is that they correctly describe a pattern of singular instances of causally related events. (Glennan, 2017, pp. 151–152)

What remains problematic is that his view adopts the notion of events (thesis E), which are essentially understood as concrete dated and located happenings. What is unclear is the relation between events and mechanisms. If events are defined as entities engaging in an activity and mechanisms as entities of organized activities, does this mean that mechanisms are organized events or rather that events parasitize on mechanisms? Briefly put, what is the truth-maker of causal claim: the mechanism or the event? This question proves to be even more pertinent if one considers Glennan’s claim that “distinguishing events from states and properties is important for my account, because on that account only events (which involve activities) can be causally productive” (2017, p. 178). If a causal claim is about one event causing another one (MC), then one event can produce another only via the mechanism (M). It seems then that for Glennan an event is individuated by its causes and effects. However, if Glennan employs the causal criterion for individuating events, and at the same time he claims that events, apart from mechanisms, are causally productive, then the issue of the causal truth-maker needs to be settled. In other words, are mechanisms causally productive in virtue of occurring events or events are causally productive in virtue of existing mechanisms?

There is, however, a second important aspect of his theory, strictly linked with the FM and CoM assumptions. If mechanisms constitute the causal structure of the world (Glennan, 2017, pp. 17–19, 239–240) as suggested by the CSW thesis, then it seems that causal relations are always grounded in an underlying mechanism. In his earlier works, Glennan suggested the existence of fundamental interactions (understood as parts of a mechanism), but there is no further mechanism that explains this interaction (Glennan, 1996, 2011). In his recent book, he again touches upon the issue of the FM. It seems that the difference between the concepts of “fundamental interactions” and “fundamental mechanisms” is limited to a terminological shift. In both cases, Glennan’s main claim remains the same: fundamental mechanisms/interactions which do not depend upon other mechanisms/interactions ground causal relationships. This claim, assuming that there are fundamental mechanisms, may be supported by the following argument:

-

1.

Causal relationships exist in the world.

-

2.

If there is no level of fundamental causal mechanisms, then there will be no causal relationships at all.

-

3.

Therefore, there must be a level of fundamental mechanisms.

However, in his recent book, he points out that the conclusion from the above reasoning is not self-evident. It seems possible that there occur infinite chains of dependencies between mechanisms and causal relationships (Glennan, 2017, p. 188), and if so, it is not necessary to conclude that causal relationships are grounded in fundamental mechanisms.

This formulation of a mechanism-dependent metaphysics of causation has been met with two counterarguments. Psillos (2004, pp. 307–311) draws attention to the problematic nature of the relationship between the concepts of mechanism and counterfactuals in Glennan’s earlier paper (1996). The latter concept can be cashed out in terms of dependence, whereby causes make a difference to their effects: for example, if the force exerted on a spring is changed, the length of the spring will change. In contrast to the counterfactual view, MC posits that causes produce their effects if there is a mechanism that connects them and that laws can be mechanically explicable if there is a mechanism that underpins them. The metaphysical problem, according to Psillos, is thus whether it is a law grounded in fundamental mechanisms that shows why certain dependence holds or whether it is the fundamental law that grounds certain dependences within mechanisms (2004, p. 309). Craver, in turn, claims that Glennan’s theory generates explanatory regress (2007, pp. 86–93). Since the mysterious connections at higher levels are grounded in other equally mysterious connections at a lower level, Glennan’s theory does not address the issue of the secret connexion. Both counterarguments point to two fundamental problems with the MC:

-

1.

If some lawful dependencies are true even though mechanisms are absent, then mechanisms are not metaphysically sufficient to ground causal relations.

-

2.

If there is an explanatory regress, then one can be attracted by proclaiming neutrality regarding “unsettled perennial metaphysical disputes” (Craver, 2007, pp. 225–226).

Firstly, it should be noted that Craver’s remark about “unsettled perennial disputes” fits very well within the “agnostic pluralism” that will be defined later. Glennan treats the above objections not as an argument for rejecting the MC but as one for modifying it. In his 2017 book, he expresses the metaphysical intuition that the world consists of “mechanisms all the way down/up.” This means that for the purposes of building the MC, it is not necessary to assume the existence of either fundamental laws (explicated by counterfactuals) or fundamental (bottom-out or top-off) mechanisms. I will leave the formal reconstruction of his theory and the detailed examination of the admissibility of the existence of infinite chains of causal mechanisms within the MC for another paper. For my current aims, it suffices to note that this is the second important issue—besides that of causal truth-makers—which Glennan has opened rather than settled.

To sum up, Glennan’s theory of causation is the most comprehensive one within the NMP. It does not fit within the straightjacket view (causal monism), which would maintain that the notion of causation refers to one kind of empirical relation only. On the contrary, his approach proves to be pluralistic on causation in the metaphysical sense:

There is on this view no one thing which is interacting or causing, and when we characterize something as a cause, we are not attributing to it a particular role in a particular relation, but only saying that there is some productive mechanism, consisting of a variety of concrete activities and interactions among entities. (Glennan, 2017, p. 148)

Glennan’s approach embraces the metaphysical pluralism on causation, based on the existence of various productive mechanisms consisting of various causally productive activities (events).

4 Metaphysical Causal Pluralism

As noted, causation is conceived of by mechanists in various, very often complementary terms, and can be analyzed by means of various causal theories. Mechanists tend to characterize causation as a productive, intrinsic, singular or general relation. Some mechanists take causation to be explicated by evoking stable regularities (Glennan, 2002; Bechtel & Abrahamsen, 2005; Leuridan, 2010; Machamer et al., 2000), generalizations (Bogen, 2005), relations of appropriately interpreted counterfactual dependence (Craver, 2007, pp. 139–160), probabilistic relations (Abrams, 2018), the transference of some property (Salmon, 1984) or the relation between events on the ground of mechanisms (Glennan, 2017, pp. 145–169). These distinctions do not primarily focus on seeking an all-encompassing view of what properties the causal relation has or what the causal relata are. Instead, they reflect the multifaceted character of causal explanations in an attempt to assess what causation is. A similar proliferation of perspectives can be noted in the case of causal relata, which are assumed to be, for example, events, properties, activities, interactions or entities (Tabery, 2004; Glennan, 2017, pp. 48–56).

4.1 Beyond the Straightjacket View

What I have stated so far is simply that there is a plurality of positions on what causation is and how it should be described.Footnote 2 At the very least, one can note that the mechanistic philosophical discussion about the metaphysics of causation has not been dominated by what Psillos calls the “straightjacket” or “monist” view (Psillos, 2009, pp. 131–151). The latter claims that there is a single, unified story to be told as to what causation is. In other words, this notion refers to the philosophers’ search for an all-encompassing theory of causation. The mechanistic literature does not fit within such a position. Salmon’s process view of causation could probably be treated as a clear example of the straightjacket view if one were to count Salmon as a mechanist. Also, while it is true that Glennan claims that there is a coherent, deep metaphysical story on causation, as has been demonstrated in the previous section, he in fact grants that there are many forms of causal claims (mechanism-based or event-based) and many “symptoms” of causation. Therefore, his effort in providing a mechanistic theory of causation does not fit within the monist stance.

If the straightjacket view does not apply, one might object that what results from such a proliferation of positions is a certain skepticism towards the general account of causation, that is, that we are left in the middle of a myriad of views touching upon a whole range of issues, such as scientific practice, philosophical accounts, empirical evidence, causal explanations and so on. Although no unique account is commonly adopted by new mechanists, such skepticism should not be of the sort associated with Hume (where it concerns the unobservability of the necessary connections) or with the claims that science does not search for causes or that the principle of causation is devoid of content. One need not necessarily be skeptical about causal knowledge if one is skeptical about the possibility of a metaphysics of causation of the sort envisaged by the straightjacket position. Mechanists are convinced that we can and do know a lot about causation in the world.

How should the mechanistic metaphysical causal pluralism be further interpreted? Two prima facie plausible and more coherent ways to grasp it are the functional view and the two-concept view of causation. While the functional view argues for a number of propositions or platitudes that the theory of causation consists in, the two-concept view claims that there are two basic concepts of causation: dependence and production (Hall, 2004). Therefore, I will analyze the aforementioned plurality of mechanistic positions on causation in the grid of these two views, which may work as a good refinement of the mechanistic metaphysics of causality. After that, I will introduce the agnostic and atheist views of causal pluralism.

4.2 The Plurality of Platitudes

According to the functional view, causation is whatever satisfies the folk theory or a given set of platitudes on causation. Platitudes can be defined as the common features of causation that any theory should accommodate. In the recent literature, such an approach is often called “the Canberra plan,” its basic idea being to provide a division of labor between philosophers and scientists. While the former should offer an a priori analysis of causal concepts, the latter should look for the things that correspond to that analysis in the world. Advocates of the functional view do not have to accept the fact that there is a deep metaphysical story to be told about the nature of causation, nor do they need to assume that the functional approach is an all-encompassing view on causation. Advocating the functional view, Menzies (2009) suggests that philosophical discussions need to attend to the folk elements of causal concepts in order to constrain or motivate systematic theories of causation.

The question for this view of causation is whether our starting point for understanding causation should be a folk conception (in which platitudes provide a description of the functional role of the causal relation) or whether we should mainly look at the sciences and their empirical results to identify the main features of the causal relations in the world. A highly instructive example of the discussion on how and to what degree our causal concepts should be empirically driven is given in the debate between J. Norton (2003; 2009a; b) and Frisch (2009a; b). Their debate shows that the demarcation between conceptual and empirical analysis in the case of different sciences is not univocal: causal concepts employed in the sciences depend on a theoretical reflection upon the empirical research being conducted in each specific field. The neat division, as the functionalist view tends to presuppose, between what is commonly assumed and what is expressed in scientific terms is difficult to achieve.

The question in this context is whether mechanists are functionalists, which seems to be the case. On the one hand, mechanists willingly attribute some platitudes to causation, such as:

-

1)

the productive platitude, whereby causes are the means to produce or prevent certain effects;

-

2)

the processual platitude, whereby causal processes propagate causal influences;

-

3)

the difference-making platitude, whereby causes make a difference;

-

4)

the explanatory import platitude, whereby causes explain their effects;

-

5)

the grounding platitude, whereby mechanisms ground causal relations; or.

-

6)

the evidential import platitude, whereby knowing that c occurred and that c causes e gives us the reason to expect that e will occur.

On the other hand, most mechanists would not be happy about the adoption of the functionalist view or Canberra planning. The fact that they attribute these different platitudes of causation does not commit mechanists to the claim that a good theory of causation should accommodate all of them, a subset of them, or some firm pre-philosophical intuitions about what causation is. Mechanists often use a number of propositions to fix the reference of causation. Moreover, they are aware that the neat division between conceptual analysis and empirical investigation—as a consequence of the formulation of platitudes—is not as clean as our intuitions may suggest (Glennan, 2017, p. 12). It is, therefore, possible that one might start reasoning about causation with common-sense assumptions. However, these assumptions should not be considered immutable. On the contrary, they may need some revision in light of certain empirical results of our best and currently adopted scientific theories. Mechanists understand causation in a functional way, whereby various aspects in the debate on causation are in continuous interaction, and therefore neither the artificial division of labor between science and philosophy nor the adoption of a priori causal platitudes is a good solution. Although the functional view can accommodate various platitudes, it is not clear how one should decide on using one platitude over another, nor is the folk theory of causation given in a compelling way. Thus, the functional view still does not cover all of the NMP’s aims.

4.3 Just the Two-Concept View?

The case for this approach has been clearly made by N. Hall in his pivotal paper titled “Two Concepts of Causation,” in which he distinguishes between causation as dependence and causation as production (2004). Looking at the mechanistic literature, it can be noted that it is permeated with this dual view of causation. Certainly, some authors are more inclined to deploy the concept of dependence/relevance, which is comparative and counterfactual in character. Others focus more on the spatiotemporally continuous properties of causal production conceived of as a single, intrinsic relationship between specified relata. Glennan (2009; 2017, pp. 163–168) defends the position that the difference-making and productive views are not really rival theories. In fact, mechanists generally look for causally relevant information provided by the use of counterfactuals and manipulations, which can then be filled in with mechanistic details about causal processes.

From the mechanistic perspective, the two-concept view is genuinely egalitarian in the sense that the two approaches are equally acceptable accounts of causation. The way to make one set of intuitions regarding causation—difference-making or productivity—privileged in relation to the other is rather dictated on a case-by-case basis by the specific explanandum and by the explanatory aims at stake. The two-concept view is on the face of it a semantic view about concepts rather than metaphysics, though it has metaphysical consequences. According to it there is not something like “the” causal relationFootnote 3. However, if for each of the concepts, there is supposed to be a metaphysical matter of fact as to how causation is to be defined, it seems that the two-concept view ends up with two straightjacket views. When reading such prominent mechanists as Craver and Glennan, it does not seem that they assume that there is an all-encompassing metaphysical matter of fact that causation is nothing but a pure difference-making relation or a pure productive relation, or that there are two straightjacket views. Rather, it seems that there is a difference in terms of emphasis. As mentioned before, Craver is more focused on the difference-making account, while Glennan favors the productive one. Certainly, for them, production and dependence (while being conceptually distinct) are strictly interwoven and further complemented by other causal concepts.

Is it then correct to interpret the mechanistic agenda in the grid of the two-concept view? Glennan, for instance, argues in the context of this view “that mechanisms come first, in the sense that the causal efficacy of manipulations comes from mechanisms, and that the truth-makers for counterfactual claims about possible interventions are actual mechanisms” (Glennan, 2017, p. 168). In their joint paper, Craver et al. (2021), in agreement with Glennan (2017), claim that

regardless how productivity is ultimately understood, manipulability via experiments (interlevel or otherwise), and with it, the truth of Woodwardian counterfactuals, is evidence for, rather than constitutive of, the productive continuity at the heart of every mechanism. (p. 8823)

Certainly, both concepts—production and difference-making—are crucial to the mechanistic view of causation. However, from the metaphysical point of view, as the above quote suggests, the authors consider productivity as being at the heart of mechanisms and the difference-making approach as being the evidence for that. So, instead of the two-concept view, do we end up with the mechanistic straightjacket view of causation conceived of as productive continuity? In what follows, I will argue that such a conclusion is incorrect.

4.4 Causal Agnosticism or Atheism?

At the beginning of this article, I noted that mechanists are causal realists who aim at unravelling the mind-independent causal structure of the world. Nonetheless, it seems that mechanists tend to oscillate, if we are to use Psillos’s labels, between an agnostic and an atheistic view of causation. These two positions can be defined in the following way:

Agnostic causal pluralism: there might be a deep and unique nature to causation—and hence a metaphysical fact of the matter as to what causation is—though there are many symptoms of it and many ways (none of which is privileged) to identify its presence.

Atheist causal pluralism: there is nothing single and deep that unites all the symptoms of causation and makes them track the unique nature of causation. Causation is a rather loose condition with no single underlying nature. (Psillos, 2009, p. 142)

First of all, it is important to note that these labels—agnosticism and atheism—are not about causation itself, since all new mechanists are causal realists, but about causal pluralism. The dominant view among new mechanists in this case seems to be agnosticism on metaphysical pluralism. As I have already indicated, Craver’s view fits within this approach. More specifically, while Craver, Glennan and Povich argue that the metaphysical truth-maker of constitutive relevance claims is the “causal betweenness,” they point out that the latter term cannot be analyzed exhaustively in terms of chance-raising and that one “must appeal in addition to a continuous causal process linking a distal cause to its effect” (Craver et al., 2021, p. 8823). This means that the concept of a productive process between an effect and its cause provides the resources needed to understand the productive continuity that holds between higher level-events. On the one hand, the authors refer to the notion of productivity (quoting the works of Anscombe (1993), Bogen (2008), Machamer, Darden & Craver (2000), and Salmon (1984) as if it was metaphysically the basic one). On the other hand, while they do not aim to resolve the metaphysical question of causal productivity, they suggest that “regardless how productivity is ultimately understood” (Craver et al., 2021, p. 8823) or “whatever productivity is” (p. 8826), it is at the heart of every mechanism. I think that this clearly reveals their agnostic view on causation, that is, a view that there might be a deep and unique nature to causal productivity and that there is, among other things, a very important symptom of it: constitutive relevance. For these authors, the ontological truth-maker of relevance is the causal betweenness, which may be identified in many ways. A sufficient but not necessary one is their “matched interlevel experiments” (MIE) account.

Are all mechanists agnostic on causation? Machamer (2004) and Bogen (2008) are probably the exceptions. As mentioned before, they take activities as a primitive concept and assume that there may be many kinds of acts. Their position proves to be strongly pluralist on causation. Although they are pessimistic about saying anything in general about activities, they do not neglect the epistemic importance of regularities. Furthermore, for them, “the evidence leaves no room for reasonable doubt about either the occurrence of the causally productive activities or the correctness of at least some widely accepted qualitative claims about how they do their work” (Bogen, 2008, p. 122). I would also argue that Glennan’s view of productive mechanisms should not be treated as an agnostic one, because he has firmly stated that facts about mechanisms are the basic ones. As I have argued in the previous section, his theory of causation is focused on the existence of a variety of productive mechanisms consisting of various causally productive events. Thus, while Glennan, Machamer and Bogen are pluralistic on causation, they are not agnostic.

The atheistic view, as Psillos suggests, means that causation is treated as a loose condition with no single underlying nature. According to this position, there are many symptoms of causation, and it seems “that there is no reason to choose one among the many symptoms of causation as being privileged (or constitutive of causation)” (Psillos, 2009, p. 143). In short, this stance suggests that there is a pluralism at the level of symptoms, but at the level of metaphysics, it is atheistic, which means that there is no unique metaphysical nature of causation. Importantly, this view does not rule out causal knowledge as such, but claims that we do not know what causation is. So, are new mechanist atheistic on causation?

It is true that, at the first glance, they seem to shift the issue from metaphysics to the epistemology of causation. With the exception of Glennan, who is clear on his metaphysical interest in causation, most of the remaining mechanists seem to be more focused on explanatory practices within various sciences and thus on some epistemic constraints on causation. In fact, a vast amount of mechanistic literature is dedicated to the question of acquiring causal knowledge and offering good causal explanations. Such a mechanistic attitude towards causation is not an example of causal anti-realism, as I have explained from the beginning; instead, its thrust is that causal truths have a plurality of truth-makers which probably, at the expense of metaphysical queries, do not share anything deep in common. However, it is not the case that mechanists explicitly exclude the possibility that causation has a deep metaphysical nature. Arguing that there are many symptoms of it and many ways to identify its presence, they are either agnostic on the issue, or, like Bogen, Glennan and Machamer, clear in their focus on the metaphysical nature of causation. Rather, the fact that causation is treated by most mechanists through its symptoms shows that the question of whether causation has a unique metaphysical nature is not relevant to their purpose. This does not mean that they are committed to the atheistic view that there is no single underlying nature of causation or that there cannot be one. Still, I would prefer to leave the issue of whether there is a need to assume a deep and unique metaphysical nature of causation for another occasion.

5 Beyond Trivial Pluralism

The claim that mechanistic metaphysical causal pluralism consists in the assertion that there can be different kinds of causal relations in the world may sound trivial. However, as has been argued so far, new mechanists are pluralistic about causal relata, platitudes, concepts and symptoms. In the last case, this means that there are many ways to identify a deep metaphysical underlying structure of causation. Let us ponder this claim.

It seems that Glennan’s theory may be interpreted as one that advances metaphysical pluralism with regard to the underlying causal structure, since it evokes the existence of various productive mechanisms as the glue of causal relations. According to him, when we characterize something as a cause, we are saying that there is some productive mechanism consisting of a variety of activities and interactions among entities. Production, which is synonymous to causation, is the capacity of mechanisms conceived of as causal systems. Causal production is not one thing but many, since “there are different kinds of production corresponding to different kinds of activities and interactions” (Glennan, 2017, p. 174). If “there are many kinds of causal production corresponding to the many ways that different activities and interactions can produce change” (Glennan, 2017, p. 155), then many kinds of causal relations are also present in the world. One may object that it is rather a platitude that a given effect can have multiple kinds of causal production. For instance, blood pressure can be raised or lowered by various causes and interventions, and windows can be broken in different ways. It seems, however, that Glennan’s position is to take the variety of mechanisms as a primitive fact regarding the underlying causal structure. For Glennan, all causation requires activity, and activities are plural, but at the same time, he emphasizes that activities and entities are “mechanism-dependent.” Bogen and Machamer are advancing the metaphysical pluralism in a similar way, the difference between them and Glennan being that they explicitly take the plurality of activities as a primitive fact regarding the underlying causal structure.

Although new mechanists are sometimes accused of being physicalist reductionists (Rosenberg, 2018), their empirically-driven philosophical discussions on causation do not seem to be either based on mere compositional reductionism or limited solely to the field of physics (Craver, 2001). Referring to compositional reductionism, mechanistic causal models are not mere nothing-but explanations (Silberstein, 2002), since they aim at integrating multiple levels of complexity. Although it is not my intention to discuss in detail the issue of mechanistic levels of explanation (Craver, 2013; Kästner, 2018; Woodward, 2008), I want to emphasize that some philosophers or scientists have come to the view that the language of higher-level theories or descriptions is being retained merely as a kind of shorthand way of talking about the lower-level stuff. The latter view, known as compositional reductionism (Gillett, 2016, pp. 103–139), however, is not the one correctly characterizing mechanistic explanation. In other words, invoking various mechanisms involved in certain processes does not necessarily lead to the adoption of a physicalist nothing-but stance. In other terms, a compositional relation that enables new mechanists to explain higher-level entities/activities to a certain degree in terms of lower-level entities/activities does not entail that higher-level entities/activities are nothing-but lower-level physical ones.

As regards physical reductionism, which claims that all facts are obtained in virtue of the spatiotemporal distribution of the fundamental entities or activities, W. Salmon’s (1984) and P. Dowe’s (1992) accounts of causation may seem to be prone to such a view. While Salmon is particularly focused on causation conceived of as the transmission of something from cause to effect via a continuous spatiotemporal causal process, Dowe’s theory of causation is mainly expressed in terms of “conserved quantities.” Both these theories urge us to look at the causal order of higher-level interactions as coming out of lower-level physical processes. This view has sometimes been combined with the conviction that properly identified, purely physical difference makers with more and more details of implementation entail that other factors acting at higher levels of analysis are to be treated as explanatorily irrelevant (Campbell & Bickhard, 2011). As a consequence, causality was understood at most as a vague philosophical label standing for the fact that everything is actually composed of microphysical entities and governed by microphysical laws. The mechanistic view on causation is not limited to such a microphysicalist view. For new mechanists, causation is a relation that not only exists at the microphysical level of reality but also “occurs at all levels of reality as a real, and hence not-reducible, relation” (De Vreese, 2009, p. 217).

Finally, one may object that mechanistic pluralism is nothing more than a pragmatic approach, that is, that it endorses the multiplicity of metaphysical positions as long as they are useful for explanatory aims. Pragmatism itself may be mainly motivated by, say, explanatory, experimental and causal pluralism and by the idea that scientific theories are necessarily underdetermined by the available data (Agazzi, 2017; Saatsi, 2018). As a consequence, pragmatists generally tend to think that the value of scientific concepts and theories is determined not by whether they are true and provide genuine explanations but by the extent to which they are useful and efficient in making accurate empirical predictions. There is, however, a sense in which mechanistic pragmatism, if one wants to call it that, goes beyond such a stance. In fact, the NMP aims at providing genuine explanations of causal processes. The kind of mechanistic causal pluralism discussed above is neither guided by the monist imperative nor is it discouraging interaction between various approaches at hand (Campaner, 2019). On the one hand, mechanistic pluralism explicitly endorses the variety of approaches to causation; on the other, it does not commit one to the single correct metaphysical theory of causation (Wimsatt, 2007).

6 Conclusions

If one looks at the mechanistic talk about causation and causal explanations, it becomes clear that there is a plethora of views on the issue. Mechanists are strongly interested in tracing causal relations in order to form certain explanations and generalizations of phenomena with respect to specific scientific disciplines.

The new mechanistic view of causation can be described as metaphysical causal realism and metaphysical causal pluralism. While the former term means that causality is a mind-independent phenomenon, the latter suggests the recognition that there are different kinds of causal relations and causal relata in the world. Although many mechanists lean towards the agnostic view, philosophers such as Glennan, Machamer and Bogen are clear in their focus on the metaphysical nature of causation. These authors are not agnostic on causation. On the contrary, they adopt the metaphysically pluralist stance, assuming a variety of productive mechanisms (as in the case of Glennan) or kinds of activities (as in the case of Machamer and Bogen) as primitives. I have also argued that mechanists should not be treated as atheists on causation. In the case of Glennan’s theory, I have noted that there are two issues which demand further exploration: the relation between events and mechanisms and the admissibility of the existence of infinite chains of causal mechanisms.

The plurality of views on causation present within the NMP does not mean that mechanists are just mere pragmatists. On the contrary, it seems that their agnosticism on causation or their advanced metaphysical causal pluralism aims at deciphering the complexity of the causal structure of the world. Although there is no univocal mechanistic solution to metaphysical questions about the nature of causation and of causal knowledge, I nevertheless interpret this aporetic situation within the mechanistic framework as an “open end.” From the point of view of philosophy, it is not without significance.

Notes

Although J. Woodward and other counterfactualist philosophers (e.g., P. Menzies, H. Price) do not consider themselves mechanists, their contribution has undoubtedly influenced the mechanistic thinking about causation and explanation according to the notion of difference-making.

The reader may expect that the mechanistic concept of causation should be discussed in reference to various scientific domains, since new mechanists are focused on scientific practice in formulating causal explanations. If one focuses on a variety of scientific domains, this may result in causation being understood differently in the case of, for example, quantum particles, signal transmission in neurons, the transfer of viruses, etc. I agree that mechanistic causation should be confronted with the sciences. In fact, such a confrontation is necessary in order to provide mechanistic models of causation in the context of research practice. However, this issue is beyond the scope of my paper, which is written from the point of view of the general philosophy of science.

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for raising up this point.

References

Abrams, M. (2018). Probability and chance in mechanisms. In S. Glennan, & P. Illari (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of mechanisms and mechanical philosophy (pp. 169–184). Routledge.

Agazzi, E. (Ed.). (2017). Varieties of scientific realism. Objectivity and truth in science. Springer.

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1993). Causality and determination. In E. Sosa, & M. Tooley (Eds.), Causation (pp. 88–104). Oxford University Press.

Baumgartner, M., & Gebharter, A. (2016). Constitutive relevance, mutual manipulability, and fat-handedness. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 67(3), 731–756.

Bechtel, W., & Abrahamsen, A. (2005). Explanation: A mechanist alternative. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 36(2), 421–441.

Bechtel, W., & Richardson, R. C. (2010). Discovering complexity: Decomposition and localization as strategies in scientific research. MIT Press.

Bogen, J. (2005). Regularities and causality; generalizations and causal explanations. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C, 36(2), 397–420.

Bogen, J. (2008). Causally productive activities. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 39(1), 112–123.

Bokulich, A. (2016). Fiction as a vehicle for truth: Moving beyond the Ontic Conception. The Monist, 99(3), 260–279.

Campaner, R. (2013). Mechanistic and neo-mechanistic accounts of causation: How Salmon already got (much of) it right. Metatheoria, 3(2), 81–98.

Campaner, R. (2019). Commentary: Plurality and pluralisms for the social sciences. In M. Nagatsu, & A. Ruzzene (Eds.), Contemporary philosophy and Social Sciences. An interdisciplinary dialogue (pp. 29–37). Bloomsbury Academic.

Campaner, R., & Galavotti, M. C. (2007). Plurality in causality. In P. Machamer, & G. Wolters (Eds.), Thinking about causes. From Greek philosophy to modern physics (pp. 178–199). University of Pittsburgh Press.

Campbell, R. J., & Bickhard, M. H. (2011). Physicalism, emergence and downward causation. Axiomathes, 21, 33–56.

Cartwright, N. (2004). Causation: One word, many things. Philosophy of Science, 71(5), 805–819.

Chakravartty, A. (2005). Causal realism: Events and processes. Erkenntnis, 63(1), 7–31.

Craver, C. F. (2001). Role functions, mechanism, and hierarchy. Philosophy of Science, 68, 53–74.

Craver, C. F. (2007). Explaining the brain: Mechanisms and the mosaic unity of neuroscience. Oxford University Press.

Craver, C. F. (2013). Functions and mechanisms: A perspectivalist view. In P. Huneman (Ed.), Functions: Selection and mechanisms (pp. 133–158). Springer.

Craver, C. F., & Darden, L. (2013). Search of mechanisms: Discoveries across the life sciences. The University of Chicago Press.

Craver, C. F., & Tabery, J. (2019). Mechanisms in science. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/science-mechanisms/.

Craver, C. F., Glennan, S., & Povich, M. (2021). Constitutive relevance & mutual manipulability revisited. Synthese, 199, 8807–8828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03183-8.

De Vreese, L. (2009). Disentangling causal pluralism. In R. Vanderbeeken, & B. D’Hooghe (Eds.), Worldviews, science, and us: Studies of analytical metaphysics: A selection of topics from a methodological perspective (pp. 207–223). World Scientific Publishers.

Dowe, P. (1992). Wesley Salmon’s process theory of causality and the conserved quantity theory. Philosophy of Science, 59(2), 195–216.

Frisch, M. (2009a). The most sacred tenet? Causal reasoning in physics. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 60(3), 459–474.

Frisch, M. (2009b). Causality and dispersion: A reply to John Norton. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 60(3), 487–495.

Gillett, C. (2016). Reduction and emergence in science and philosophy. Cambridge University Press.

Glennan, S. (1996). Mechanisms and the nature of causation. Erkenntnis, 44(1), 49–71.

Glennan, S. (2002). Rethinking mechanistic explanation. Philosophy of Science, 69(S3), S342–353.

Glennan, S. (2009). Productivity, relevance, and natural selection. Biology & Philosophy, 24(3), 325–339.

Glennan, S. (2010). Mechanisms, causes, and the layered model of the world. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 81(2), 362–381.

Glennan, S. (2011). Singular and general causal relations: A mechanist perspective. In P. M. Illari, F. Russo, & J. Williamson (Eds.), Causality in the sciences (pp. 789–817). Oxford University Press.

Glennan, S. (2017). The new mechanical philosophy. Oxford University Press.

Glennan, S., Illari, P., & Weber, E. (2022). Six theses on mechanisms and mechanistic science. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 53, 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-021-09587-x.

Godfrey-Smith, P. (2009). Causal pluralism. In H. Beebee, C. Hitchcock, & P. Menzies (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of causation (pp. 326–337). Oxford University Press.

Hall, N. (2004). Two concepts of causation. In J. Collins, N. Hall, & L. Paul (Eds.), Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 225–276). MIT Press.

Harinen, T. (2018). Mutual manipulability and causal inbetweenness. Synthese, 195(1), 35–54.

Hempel, C. G. (1965). Aspects of scientific explanation and other essays in the philosophy of science. The Free Press.

Hitchcock, C. (2007). How to be a causal pluralist. In P. Machamer, & G. Wolters (Eds.), Thinking about causes. From Greek philosophy to modern physics (pp. 200–221). University of Pittsburgh Press.

Illari, P., & Williamson, J. (2011). Mechanisms are real and local. In P. M. Illari, F. Russo, & J. Williamson (Eds.), Causality in the sciences (pp. 818–844). Oxford University Press.

Illari, P., & Williamson, J. (2012). What is a mechanism? Thinking about mechanisms across the sciences. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 2(1), 119–135.

Kaiser, M. I. (2018). The components and boundaries of mechanisms. In S. Glennan, & P. Illari (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of mechanisms and mechanical philosophy (pp. 116–130). Routledge.

Kästner, L. (2018). Integrating mechanistic explanations through epistemic perspectives. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 68, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2018.01.011.

Kellert, S. H., Longino, H. E., & Waters, C. K. (Eds.). (2006). Scientific pluralism. vol. XIX. University of Minnesota Press. Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science.

Leuridan, B. (2010). Can mechanisms really replace laws of nature? Philosophy of Science, 77(3), 317–340.

Leuridan, B. (2012). Three problems for the mutual manipulability account of constitutive relevance in mechanisms. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 63(2), 399–427.

Machamer, P. (2004). Activities and causation: The metaphysics and epistemology of mechanisms. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 18(1), 27–39.

Machamer, P., Carden, L., & Craver, C. F. (2000). Thinking about mechanisms. Philosophy of Science, 67(1), 1–25.

Matthews, L. J., & Tabery, J. (2018). Mechanisms and the metaphysics of causation. In S. Glennan, & P. Illari (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of mechanisms and mechanical philosophy (pp. 131–143). Routledge.

Menzies, P. (2009). Platitudes and counterexamples. In H. Beebee, C. Hitchcock, & P. Menzies (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of causation (pp. 341–367). Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, S. D. (2003). Biological complexity and integrative pluralism. Cambridge University Press.

Norton, J. D. (2009a). Causation as folk science. Philosopher’s Imprint, 3(4), 1–22.

Norton, J. D. (2009b). Is there an independent principle of causality? British Journal of Philosophy of Science, 60(3), 475–486.

Pearl, J., & McKenzie, D. (2018). The book of why: The new science of cause and effect. Basic Books.

Psillos, S. (2004). A glimpse of the secret connexion: Harmonizing mechanisms with counterfactuals. Perspectives in Science, 12(3), 288–319.

Psillos, S. (2009). Causal pluralism. In R. Vanderbeeken, & B. D’Hooghe (Eds.), Worldviews, science, and us: Studies of analytical metaphysics: A selection of topics from a methodological perspective (pp. 131–151). World Scientific.

Psillos, S., & Ioannidis, S. (2019). Mechanisms, then and now: From metaphysics to practice. In B. Falkenburg, & G. Schiemann (Eds.), Mechanistic explanations in physics and beyond (11 vol., pp. 11–31). Springer. European Studies in Philosophy of Science.

Romero, F. (2015). Why there isn’t inter-level causation in mechanisms. Synthese, 192, 3731–3755.

Rosenberg, A. (2018). Making mechanisms interesting. Synthese, 195, 11–33.

Saatsi, J. (Ed.). (2018). The Routledge Handbook of scientific realism. Routledge.

Salmon, W. (1984). Scientific explanation and the causal structure of the world. Princeton University Press.

Schiemann, G. (2019). Old and new mechanistic ontologies. In B. Falkenburg, & G. Schiemann (Eds.), Mechanistic explanations in physics and beyond (11 vol., pp. 33–46). Springer. European Studies in Philosophy of Science.

Silberstein, M. (2002). Reduction, emergence and explanation. In P. Machamer & M. Silberstein (Eds.), The blackwell guide to the philosophy of science (pp. 80–107). Blackwell

Tabery, J. G. (2004). Synthesizing activities and interactions in the concept of a mechanism. Philosophy of Science, 71(1), 1–15.

Williamson, J. (2011). Mechanistic theories of causality part I. Philosophy Compass, 6(6), 421–432.

Wimsatt, W. C. (2007). Re-engineering philosophy for limited beings: Piecewise approximations to reality. Harvard University Press.

Woodward, J. (2002). What is a mechanism? A counterfactual account. Philosophy of Science, 69, S366–S377.

Woodward, J. (2008). Comment: Levels of explanation and variable choice. In K. Kendler, & J. Parnas (Eds.), Philosophical issues in psychiatry: Explanation, phenomenology, and nosology (pp. 198–237). John Hopkins University Press.

Wright, C., & van Eck, D. (2018). Ontic explanation is either ontic or explanatory, but not both. Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy, 5(38), 997–1029.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks goes to Tomasz Jarmużek for his suggestions, which helped me in the development of the section dedicated to S. Glennan’s theory of causation. Lastly, I extend my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers who gave exact suggestions that vastly improved and changed the initial material.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Science Center, Poland, 2021/41/N/HS1/01338. For the purpose of Open Access, the authors have applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oleksowicz, M. Metaphysical Causal Pluralism: What Are New Mechanists Pluralistic About?. Philosophia 51, 2457–2478 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-023-00690-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-023-00690-5