The class began with me presenting data on the pay gap between men and women in both developed and developing countries. The discussion soon became animated, and gradually escalated to heated debates between male and female students. While male students argued that women worked less, and therefore lower salaries were justified, female students found such arguments baseless. In an attempt to prevent the discussion from getting out of hand, I offered recent examples of top female leaders from varied sectors (hospitals, universities, etc.) complaining of lower salaries than male counterparts. I hoped to make the point that even high performing women experience gender-based discrimination. This led male students to remark that my own gender was biasing my arguments. This left me wondering… I was upset but could not express my sentiments for fear of being negatively perceived… yet, I spent an uncomfortable night replaying the scene from the classroom in my mind over and over again….

—A female business ethics professor in a European school.

Abstract

Business ethics (BE) professors play a crucial role in sensitizing business students toward their future ethical responsibilities. Yet, there are few papers exploring the ethical challenges these professors themselves face while teaching BE. In this qualitative paper, we rely on the lenses of ethical sensemaking and dramaturgical performance, and draw from 29 semi-structured interview conducted with BE professors from various countries and field notes from 17 h of observation of BE classes. We identify four kinds of rationalities that professors rely on for making sense of in-class ethical challenges, eventually leading them to engage in one of four corresponding types of performances. By juxtaposing high and low scores of two underlying dimensions (degree of expressivity and degree of imposition), we offer a framework of four emerging performances. Additionally, we show that professors can shift from one performance to another during the course of their interactions. We contribute to performance literature by demonstrating the plurality of performances and explaining their emergence. We also contribute to sensemaking literature by offering support to its recent turn from an episodic (crises or disruption-based) to a relational, interactional, and present-oriented understanding. Since professors’ performances have an impact not only on their own teaching experiences but also on students’ learning experiences, undermining these would result in compromising the efforts that business schools have been making toward sensitizing future managers to their ethical responsibilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Business ethics (BE) is a form of applied ethics that examines ethical rules and principles within a commercial context, the various ethical problems that can arise in a business setting, and any special duties that apply to persons who are engaged in commerce (Christensen et al., 2007). Although rarely evoked as a topic till as late as the 1970s, interest around BE started gaining momentum with the establishment of the European Business Ethics Network (EBEN) in 1987, which reported close to 1400 members from 40 countries a decade ago (Van Liedekerke & Demuijnck, 2011). Since then research on BE has undergone substantial development, with the number of articles published on the topic increasing exponentially. Simultaneously, with mounting accusations of unethical practices in businesses, calls for teaching ethics in business schools have also gained momentum (Cornelius et al., 2007; Sims & Felton, 2006). Many governmental and accreditation bodies now require business ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), or responsible leadership to be included in business school curricula. Christensen et al. (2007) note a five-fold increase in the number of stand-alone ethics courses in the two decades leading up to their investigation. DeGeorge (2010) delineated two emerging branches of academic BE: the philosophical branch emphasizing the normative aspects of BE, and the social sciences branch emphasizing its descriptive aspects, with the latter being more prevalent in business schools. Understandably, there is also considerable interest in research surrounding teaching BE. The Journal of Business Ethics alone has published more than 200 articles on the topic from 1999 to 2013 (Collins et al., 2014). Despite the proliferation of literature both on BE as well as on teaching the subject, there has been relatively less focus on in-class experiences of business ethics professors. More specifically, there has been little focus on the challenges, especially ethical ones, that BE professors may encounter in class, and on how they make sense of and subsequently deal with such challenges.

Among the few scholars who have focused on BE professors’ in-class experiences, some (see Macfarlane et al., 2004; Toft, 2015) acknowledge that teaching the topic raises a number of challenges, some overlapping with broader challenges associated with the teaching profession (see Clark, 2004), but others more specific to teaching BE. As an example of the latter, while many business students may find ethics courses to be thought-provoking, others may be deeply upset by their content (Clark, 2004).Footnote 1 Also, while ethics courses attempt to encourage moral reflections among students, this attempt may need to be disguised in secular, non-religious terms to avoid accusations of religious impositions, more so with secular and/or atheist audiences. Notwithstanding these studies, there has never been, to the best of our knowledge, an attempt to explore how professors experiencing such problems make sense of and deal with them. Therefore, in the present paper, we ask: How do professors teaching BE make sense of the ethical challenges they encounter in class? How do they deal with (perform in the face of) such challenges? Understandably, BE courses taught in business schools around the world might be motivated by a variety of different learning objectives, and capturing them is beyond the scope of the present paper. Therefore, we limit our focus to one such aim: to sensitize business students to the potential ethical challenges they might face in their future careers, and to encourage them to develop their independent thinking and standpoint on these issues.

To answer the research questions presented in the previous paragraph, we use the joint lenses of ethical sensemaking (Weick, 1995; Weick et al., 2005) and dramaturgical performances (Goffman, 1956). Sensemaking has been commonly defined as direct constructive deliberations in the decision-making process when individuals experience interruption in activities (Brown et al., 2015; Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015). As an extension, ethical sensemaking is defined as the process of making sense and constructing meaning with regard to moral/ethical issues (Reinecke & Ansari, 2015). Recently, there have been calls to shift from an episodic view of sensemaking to considering it as a holistic practice embedded in relational interactions between the subject and environment (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015). Scholars have also called for a move toward a social constructivist (interactional and relational) approach to sensemaking as opposed to a cognitive one. Nevertheless, barring few studies (e.g., Hales et al., 2021; Patriotta & Spedale, 2009), literature on such a relational approach to sensemaking remains underdeveloped.

Additionally, we also rely on Goffman’s (1959) work on dramaturgical performances (referred to hereafter as only ‘performances’). We believe that the practice of repeatedly (re)acting in a certain way when faced with ethical challenges in the classroom drives professors into assuming a ‘role’, which they then attempt to sustain through their subsequent performances. Once a behavioural pattern is set into place in a social interaction, it is repeated along similar features in subsequent interactions (see Patriotta & Spedale, 2009), although there is always the possibility for actors to adapt their behaviours as and when contexts evolve. Since performances have the potential to influence organizational level outcomes (Mueller, 2018; Whittle et al., 2021), we argue that the way BE professors make sense of and subsequently perform in their classes will influence not only their own experiences, but also students’ learning outcomes. Performances gone bad, would not only lead to less-than-optimal experiences for professors thereby impacting their motivation, they would also result in disenchanted and disengaged students. Taken together, these consequences will undermine the very purpose behind the creation of such courses, namely to sensitize business students to their ethical responsibilities as future managers/employees.

Goffman’s framework, first introduced over six decades ago, has guided scholarly works in many disciplines such as sociology (Raffel, 2013), education (e.g., Birnbaum, 2008), and public culture (e.g., Khan, 2020). Jacobsen and Kristiansen (2014) describe Goffman as one of the most prominent social theorists in post-war sociology, adding that his ideas continue to influence scholars in various fields. More pertinently to our research context, his framework has often been used to study interactions in the sector of training and education: for instance, between rock-climbing instructors and their trainees (Beames & Pike, 2008), the presentation of selves by college students on digital media (Birnbaum, 2008), and impression management among ballet students (Whiteside & Kelly, 2016). More recently, its use has been expanded from understanding human behaviour in face-to-face interactions to online interactions (see Bullingham & Vasconcelos, 2013; Hogan, 2010). Notwithstanding its popularity in other disciplines, Goffman’s work has received relatively less attention in management and organization studies (barring exceptions like Czarniawska, 2006; Manning, 2008; Ringel, 2019), compelling scholars (Patriotta & Spedale, 2009) to call for rectifying this inadequacy. Further, some scholars have drawn connections between Goffman’s work on performances and Weick’s notion of sensemaking (e.g., Czarniawska, 2006), while still others have called for Goffman’s work be extended to sensemaking research (Patriotta & Spedale, 2009). We position our present work at the confluence of these two streams of literature.

Although Goffman (1959) had hinted at different kinds of performances, as is evident from his mention of performances that might be good for the performer and those that might serve the interest of the larger community, he has not elaborated a comprehensive typology or framework of different kinds of performances. Most subsequent literature relying on Goffman’s work (see Ringel, 2019; Bullingham & Vasconcelos, 2013; Patriotta & Spedale, 2009) has also neglected this aspect. Through our qualitative study, comprised of 29 semi-structured interviews with BE professors from different countries, and field notes corresponding to 17 h of observation of BE classes, we show that BE professors display four kinds of performances emerging from four different underlying rationalities. We offer a comprehensive framework of performances emerging from high and low scores along two underlying dimensions (degree of expressivity and degree of imposition). Further, we demonstrate that professors can also shift from one kind of performance to another when the situation demands. As such, our paper lends support to the recent relational and interactional turn in sensemaking literature.

Literature Review: Sensemaking and Performance

In most mainstream literature, sensemaking has been conceptualised as the process of problem construction, interpretation, and enactment around an interrupted activity at an individual or organizational level (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015). This literature focuses on the human subjects and their need and capacity for turning complex and confusing situations into those that can be understood, thereby enabling purposeful action (Weick, 2012; Weick et al., 2005). At the individual level, threat to identity represents the basis of most sensemaking studies. Previous studies have explored how traumatic events like injuries (Maitlis, 2009) and new role expectations (Pratt et al., 2006) triggered sensemaking at the individual level. At the organizational level, focus has been on major events including strategic change (Balogun et al., 2015), and organizational crisis (Maitlis & Sonenshein, 2010). While this literature has its merit, we believe that its focus on crisis, change, or moments of disruption could be limiting, because in doing so, it overlooks the possibility that sensemaking could also occur as individuals navigate regular day-to-day interactions. This realization has inspired some scholars to call for a shift of focus from episodes of disruptions in sensemaking studies to practices rooted in dynamic relations and enactment (Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011), thereby allowing a holistic and relational outlook to the situational responses of sensemaking actors (see also Reinecke & Ansari, 2015). We position the present work along this line of thinking.

In past decades, the sensemaking literature has developed along two main axes: cognitive elaborations with mental maps/schemas, and the social constructivist pathway emphasizing identities, social interactions, and discursive dispositions. This latter axis focuses on the conversational and social practices that people engage in to produce narratives (Brown et al., 2008), stories (Boje et al., 2015) or accounts that construct a sense of shared meanings (Whittle et al., 2015). This line of work assumes that discursive (inter-)actions generate meaning and simultaneously enact the environment that people try to make sense of (Weick, 1995). Unfortunately, such interactive and relational aspects of sensemaking remain relatively less explored (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014). Notable exceptions include Patriotta and Spedale’s (2009) study wherein they use Goffman’s notion of performances to show how face games generate interaction orders leading to a working consensus within a consultancy task force. Another study by Hales et al. (2021) focuses on how lap dancers negotiate customer’s expectations through embodied interactions and embedded relationship with the materiality of the dance club. The understanding that social interactions are instrumental in sensemaking, and that these are embedded in the performance of routine practices, guides the present work.

Within the social constructivist approach, sensemaking is grounded in contextual rationality (Weick, 1993), wherein rationality implies a ‘boundedly relevant’ way to explain human behaviour’ (Kudesia, 2017, p. 8). Thompson and Wildavsky (1986) and Thompson (1996) offer a nuanced appreciation of rationality, explaining that rationality is the way in which information is attended to. It is clear that people cannot pay full attention to all incoming information at all times (i.e., the notion of ‘bounded rationality’). Yet, people tend to stop short of their physiological limits in information processing, and not everyone stops short at the same spot. In order to do this, one is required to effectively reject information, not just stop processing information.Footnote 2 Thus, rationalizing is inherently a subjective process. Combining this understanding of rationality with our focus on sensemaking, we propose that when faced with an ethical issue, professors have the possibility of drawing on different subjective realities. They employ varied rationalities to make sense of their experiences and to justify their subsequent actions (following Sonenshein, 2007). It could also be argued that since these teachers could employ different kinds of rationalities for sensemaking, they could potentially enact different kinds of performances in their ongoing interactions with students. Thus, professors become actors striving to perform in ways consistent with their initial image, but also dynamic enough to adapt their performances as the environment evolves.

We rely on Goffman’s (1959) study of social interactions to explore BE professors’ in-class experiences, because this framework is particularly suitable for examining the micro-dynamics of sensemaking endeavours (Patriotta & Spedale, 2009). There are several aspects of Goffman’s notion of performance which are relevant for our present exploration. To begin with, Goffman perceived the self to be a product of the dramatic interaction between the actor and their audience, with each person acting in a way that fits with the expectations of the audience (Beames & Pike, 2008). Goffman used the term ‘face’ to mean the image of self that a person presents to others in social encounters, and the positive social values that (s)he effectively claims for himself/herself (Goffman, 1967: 4 as presented in Patriotta & Spedale, 2009). Face should not be confused with identity; rather it is the ‘front’ that participants project on the social interaction, which may or may not align with their real selves. In our study, we find that professors use different practices, such as showcasing their expertise, to generate a specific kind of face in their classes, which they then attempt to maintain through their subsequent interactions. We also find parallels between Goffman’s (1959) notion of a stage and our experience of the classroom, and between actors’ performances and those of teachers. Although our present study focuses on professors as the artists/performers and on students as the audience, it is understood that these roles can easily be reversed. The classroom is the frontstage on which professors ‘perform’, while the informal faculty lounge, departmental meeting rooms, or shared office spaces, where they vent their frustrations and dissatisfactions, are akin to the backstage. All the activities that professors engage in while teaching BE, including but not limited to designing and delivering their lessons, using specific pedagogical tools, citing examples, encouraging a dialogue [or not] in class, etc., become part of their unique performances.

Our decision to combine sensemaking with performance finds support in recent literature citing the similarities and synergies between these two lines of work. For instance, Czarniawska (2006) notes that Goffman and Weick shared a common interest, namely, to understand the everyday life of common people engaged in activities of organizing, and a vision of life in which events and actions are inter-connected. Weick himself recognized the consistencies between Goffman’s framework and his own view that sensemaking unfolds through ongoing affirmations and revisions of the self (Weick, 1995). Yet, there were some distinctions in their works. For instance, Weick explicitly attempted to tone down the emphasis on intentional theatricality in Goffman’s view of social life, and offered a more polysemic understanding of the same. Patriotta and Spedale (2009) also draw similarities between the works of Goffman and Weick, explaining that for Weick “the grounding of identity underlying group-based interaction typically involves repeated face games during which participants attempt to influence the patterns of interaction at the same time as maintaining a coherent image of self” (p. 1228). These face games generate a frame for action, which they compare with Goffman’s notion of an ‘interaction order’, explaining that this can either lead to a working consensus (modus vivendi) or result in a state of ‘sustained disequilibrium’ which leaves the participants “to flounder in an interchange that cannot readily be completed” (Patriotta & Spedale, 2009, p. 1232). Finally, both Goffman and Weick support that sensemaking at the group level is the outcome of the individual’s behaviour within a specific context and other’s reaction to this behaviour (Patriotta & Spedale, 2009). This understanding of sensemaking places the individual at the center of social interactions.

Methodology

Data Collection

Grounded within the interpretivist tradition, we collected data through 29 semi-structured interviews of BE professors from different countries, combined with 17 h of observations of BE classes taught in English, in a French business school catering to international students. While the interviews allowed us to appreciate BE professors’ accounts of their in-class experiences, the field study allowed us to observe in real time the interactions between professors and students within the natural setting of a classroom. Combining interview transcripts with field notes not only allowed us to triangulate the data (Fitz-Gibbon et al., 1987), thereby contributing toward construct validity and rigor (Lacey & Luff, 2001), it also offered us an unexpected and novel insight compelling us to re-analyse our interview transcripts for further depth and richness.

For our interviews, we began by contacting BE professors in the business school employing two of three authors of the present paper, and then used the snowball sampling technique to recruit other interviewees known to the first set of interviewees both within and outside their employing organization. All the interviews were conducted in English, since all the respondents not only spoke the language fluently, they also taught BE in English across different countries. Ten of these 29 interviews were conducted by a research assistant recruited for this purpose in 2014/15, and the remaining interviews were conducted in 2016/17 by the third author. We started by seeking respondents’ written consent for participating in our study. Many interview questions were open ended and descriptive. Some standard questions included: What is your approach to teaching BE? Have you encountered ethical challenges in teaching this subject matter? If yes, would you offer us some examples, please? How did you face these challenges? Have you taught subjects other than BE? If yes, was this experience different from that of teaching BE? If yes, how? Although we relied on these standard questions to give direction to our interviews, we freely deviated from them when an interesting line of thinking presented itself. Interviews were conducted either face-to-face or via phone/Skype depending on where the interviewees were based. Most interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min and were recorded on a recording device. Our respondents were almost equally divided between men and women (15 men and 14 women), and represented many different nationalities. Many respondents had worked/were working in countries other than their countries of origin, and had taught BE and/or closely related topics to a variety of audiences (students enrolled in different Bachelors and Masters level programs in business schools, and from different nationalities and educational backgrounds). Our respondents ranged from 32 to 67 years of age, with most holding PhD degrees, a few with Masters level qualifications, one with a Bachelor of Science, and one holding a French aggregation level qualification.Footnote 3 While most respondents held permanent positions in their respective schools, some were visiting faculty in other schools. Table 1 provides an overview of our respondents’ profiles.

At the end of our interviews, and taking inspiration from photo voice (Molloy, 2007; Peabody, 2013), a research methodology often used for capturing abstract concepts (Harley & Hunn, 2015), we asked our respondents to depict their in-class experiences by designing comic strips using a software called MakebeliefComix.com. Unfortunately, only four respondents were able to meet this request. Nevertheless, we found these comic strips to be very insightful and have used them in our present work to add qualitative richness.

For the field study, the second author attended (as an observer) five sessions of BE classes being taught face-to-face in English at the Paris campus of a European business school.Footnote 4 Author 2 contacted the respective teachers of these classes by email three weeks before the scheduled date to seek permission, then followed up with a reminder email four days before the class date. These courses were taught to two groups of Masters level students by two different professors, a young male professor of French origin, and a senior male professor of Irish origin. The audience included both French and international students, some of whom were part of a program whereby they alternated between work and school. The students’ work experience and their international background led to interesting discussions in class, providing us with much substance for thought and reflection.

In these observation sessions, author 2 silently observed the interactions between the teacher and the students from a position in front of the class. Mason (1996) explains that whilst most ethical codes would suggest that research should not be conducted in a covert manner, it may not always be easy or possible to maintain an overt role. In the present case, author 2 let the individual professors decide whether or not they wished to divulge the researcher’s identity to the students. In the first session, the professor chose not to introduce author 2 to students, while in the other sessions, the teacher introduced her as a researcher without explicitly exposing the nature of her research project.Footnote 5 During the sessions, author 2 manually noted down bullet points of the proceedings of the class, fleshing them out into full notes during the break or in the train on her way back home. This was done immediately after the class to avoid forgetting the details. Thirty-five pages of field notes were written, thereby turning the in-class observations “from a passing event, which exists only in its own moment of occurrence, into an account, which exists in its inscription and can be re-consulted” (Geertz, 1973, p. 19). These field notes were then shared with authors 1 and 3.

Data Analysis

Before analysing the data, we transcribed the interviews. We did this ourselves, so as to maintain a sense of ‘connection’ with the data (Hales et al., 2021). Five interview transcripts were sent back to interviewees for validation to ensure that biases had not been introduced during the process of data recording. Such member-checks enhance authenticity, trustworthiness, and rigor, while simultaneously allowing respondents to participate in the research process (Lacey & Luff, 2001). Pseudonyms were assigned and all marks of identification were deleted from the transcripts to avoid respondent identification.

In the first round, we relied on inductive analysis, letting patterns emerge from the data set rather than being imposed on them (Patton, 1980). At this stage, the first and second authors coded the data from the interview transcripts independently. While the first author engaged in manual data coding, the second author used the Atlas.ti software, the underlying assumption being that the emergent themes would be more reliable if they emerged consistently despite the two authors using different tools of analysis.

The first author used content analysis to analyse the interview transcripts, treating each interview as the unit of analysis. Although content analysis usually refers to quantitative analysis of written text, Hancock’s (1998) version of it seems similar to thematic analysis (Lacey & Luff, 2001). Following Hancock’s suggestion, author 1 read and re-read the interview transcripts several times till she was completely familiar with the content of the interviews. She noted recurring emergent themes in the margin of the printed transcripts. Then a list was prepared by collecting all the themes identified earlier on. Themes pertaining to different ways of teaching business ethics were set aside as not relevant to the present study, while themes pertaining to the in-class experiences of the BE professors became the focus of the subsequent analysis. Next, thematic analysis was carried out across interviews to identify recurring themes. To facilitate this, data were organized through non-cross sectional indexing, and textual codes were determined for the different kinds of challenges encountered by the teachers of BE, and the different ways in which they navigated these challenges.

In contrast, the second author relied on the Atlas.ti software to analyse the interview transcripts. She identified 112 codes, with some focusing on the way BE was taught, and others indicating the varied ethical challenges encountered in class by our respondents and their different ways of handling these challenges. For the present paper, we focused on the second set of themes. As a second step, author 2 grouped the relevant codes resulting into 10 major codes of which 6 were pertinent to our research question. These code groups included challenges faced by the teachers, and the ways in which they navigated these challenges. The coding conducted by author 2 was then subjected to cross-code checking by author 3. While the two authors agreed on most of the codes, one of the sub-categories was the subject of some disagreement, generating some back-and-forth discussion between the three authors before consensus could be achieved.

In the second round of data analysis, the first and second authors pooled together their findings regarding ethical challenges encountered by BE professors. We noted down all the ethical challenges encountered by our respondents with a few illustrative examples of each category. As the next step, and following from our independent analyses of the interview transcripts, we found that one of the prominent themes was how our respondents faced the ethical challenges they encountered in class. At this stage, our work became more abductive in nature because we drew inspiration from two sensitizing concepts/frameworks (see Bowen, 2006): Mary Douglas’s (1970) worldviews and Michael Thompson’s (1996) rationalities. A sensitizing concept offers the user a general direction and guidance in approaching empirical instances as opposed to definitive concepts, which precisely tell the researcher what to look for (Blumer, 1954). Guided by these sensitizing concepts, we found that respondents relied on one of four kinds of rationalities to guide their performances while addressing ethical challenges encountered in class. Assuming that each kind of rationality employed during sensemaking resulted in the professor choosing to perform in a specific way, we reverted back to the interview transcripts to chart out the different kinds of rationalities and the different kinds of performances they generated. As a final step, author 3 was invited to explore if any consistent patterns could be traced between respondents’ performances and situational variables (such as the nature of ethical problem at hand, age, gender, number of years of teaching experience, etc.). She found no support for such relationships.

In round 3 of the data analysis, authors 1 and 2 analysed, at first separately and then collectively, the 35 pages of field notes through thematic analysis. These field notes were labelled as per the date and site where the observations were conducted. They were then read and re-read several times, till recurring themes could be identified across the data set. We had originally intended to use these field notes only to support or challenge the themes emerging from the analysis of interview transcripts. However, the field notes gave us an indication for a new and unintuitive finding, compelling us to revisit and reanalyse interview transcripts. Thus, our field study not only contributed to the credibility (truth value of findings in a naturalistic inquiry study) of findings emerging from the analysis of interview transcripts, it also compelled us to explore our data for new findings. Finally, we had also received four responses from respondents to our request to design comic strips, which serve to elucidate our respondents’ in-class experiences. Yet, since saturation was not reached, we use these comic strips only to enhance the descriptive richness of our study.

Findings

Four Rationalities Guiding BE Professors’ Sensemaking

Our interviews revealed many ethical challenges encountered by BE professors in class. While some of these had to do with the discussion of sensitive topics (e.g., homosexuality) with students from conservative backgrounds (BD, female, Romanian, 45 years), others revealed professors’ discomfort in critiquing practices students were accustomed to in their home countries (for example, discussing corruption with Indian or Lebanese students) (RV, female, French, 60 years), while still others revealed professors’ inability or unwillingness to pronounce a right or wrong kind of answer when discussing an ethical dilemma (e.g., vaccine nationalism in the context of Covid 19) (field notes, 24th October, 2022). In response to these varied ethical challenges, respondents relied on four kinds of rationalities, which we label as follows: self-focused, group-focused, principle-focused, or survival-focused.

Professors relying on the self-focused rationality safeguard their personal beliefs and convictions on the topic at hand by not exposing them. This is exemplified by the following quote from one respondent, “I don’t bring my values in … I am not there to share my views- I am there to provide ideas and theories and perhaps insight, but I do not need to follow them… In the end you teach the syllabus” (SW). This respondent clearly safeguards his views and values by not exposing them to his students, and prefers focusing on the objective goals as stated in the syllabus. The same professor prefers not to discuss topics he considers ‘personal’. He explains, “I do not find it easy to talk about religion because I regard that as personal” (SW). In an effort to safeguard his personal belief system in the public setting of a classroom, this professor prefers to avoid the topic of religion altogether. This does not, however, imply that this professor or others like him, are any less committed to their students’ learning outcomes than professors mobilizing other kinds of rationalities. On the contrary, by teaching BE in a neutral way devoid of their own judgements, many of them hope to provide students with the space to develop their own viewpoints. One such professor comments, “…the balance of the delivery in an objective way and the management of discussion in a non-judgmental way [is done] so that it can maintain both the process of information…[…]….but also inspiration, because someone might hear something that triggers them to reconsider their position” (CN).

In contrast, the group-focused rationality is evident when professors leverage the different viewpoints within the classroom combined with their own standpoints to arrive at a collective and informed consenses (even if partial) on a topic. We also found evidence for the group-focused rationality in our field work. For instance, when the topic of availability of Covid 19 vaccines across countries was evoked in one session, students expressed a variety of viewpoints generating a complex and intense discussion involving vaccine nationalism, profit-making by companies versus meeting vaccine needs of poor nations, the role of the United Nations, etc. The teacher not only encouraged students to express their diverse and sometimes conflicting viewpoints, he also incited them to reflect on where their viewpoints converged and where they diverged. Another BE professor described the following scenario emerging from a heated debate in her class concerning gender-based pay segregation: “I want to open the room and let anyone speak- I do not want to shoot them down, …[I] try to offer information and facts- and usually other students will start speaking. […] I did not want to sit and not do anything- usually I ask questions, and then I bring in the laws in different countries- I hate to bring in laws- but that works as a baseline” (RJ). This quote reveals the professor’s commitment that all students need to be given the opportunity to express themselves, especially those who disagree with the dominant voices. She clearly takes a proactive stance (I did not want to sit and not do anything). She also, even if reluctantly, evokes the law as a baseline to facilitating discussions, thereby drawing the boundaries within which the discussion may evolve. Finally, she explains how she resolved the problem, “Last time I was prepared. I had us all gather in a circle. I said to the students- you are going to talk about this-…- and […] you will elect representatives…they elected a young man from France- and he started asking questions- […]- and then they were blaming the country- it was not so personal- and it lasted for about 2 ½ hours- they did resolve the issues in the end. The louder men quietened down, and the women started speaking up. I thought that was an interesting development in the classroom and I used it as a tool to help everyone in the room talk about the issue” (RJ). Thus, realizing the diversity of viewpoints on the issue of gender, this professor provided students, especially those who were previously silent, the space to express themselves, thereby letting the class as a whole to arrive at a state of partial (if not complete) consensus on the topic. This professor provided us the following comic strip (see Fig. 1 below) expressing this experience:

The third rationality is principle-focused, where teachers focus either on their personal priciples or broader societal principles as the basis for navigating ethical challenges in the classroom. Some respondents cite personal religious convictions as a basis for their stance, “I’m a Christian and I am a reformed Protestant- and this has some implications on how you conduct business and live day-to-day life. Some students do not have sufficient culture of religions and ideas of the west” (JV). This example is evidently very different from the earlier instance cited in this sub-section where the respondent refrains from evoking religion (because he considers it a private matter). Interestingly, and in contrast to the afore-cited example, another respondent who identified as an atheist, used her logical beliefs within which to ground her reflections, as seen in this quote “…I cannot share with them my [religious] faith- I usually share my perspective… I tell the students that I am an atheist and that shows them where I am coming from. Every course I say that I am an atheist and then go on to discuss other things” (SL). As these two examples show, both religion and atheism can serve as guiding principles influencing professors’ rationality. In another example, a respondent cites normative principles as guiding his standpoint on ethical issues. He explains, “I believe that tobacco companies are like organized crime, and I give my arguments- I do not hide- I have a normative position- I tell students that this is my position- they can have a different one- but they must have good argument” (PG). Although holding a negative view of tobacco companies is fairly common, this professor presents a rather strong stance, likening these companies to organized crimes based on normative principles.

Finally, the fourth rationality is focused on survival or self-protection. This kind of rationality is employed by BE professors who do not necessarily take a stance, not because they wish to facilitate student learning (as in the case of self-focused rationality) but rather to protect themselves from potential backlash. Consider this example of a BE professor experiencing some problems with her employing organization, “The challenge for me has been to pretend to the students that all is fine, and to represent the school well when things are not OK. Not expressing things to the students for large problems- they might not be aware of it- but it is stuff that is kept quiet and you are told to keep quiet. ….. It was very difficult to teach BE in a situation when I was being treated unethically- students did not really know, and if I told them and gave examples- I would get into trouble….It was difficult to be authentic and talk about BE and be pretending” (HM). As evident in this example, the respondent could not freely share her experiences with students for fear of reprimand from dominant organizational players. Another respondent reported, “I have an ethical dilemma about the organization that I am working for—it does not necessarily treat its employees in an ethical way at all times. Sometimes, I get the feeling that employees are treated like objects, because the routines become the end and the people become the means to meet that end. This becomes very challenging particularly when you are delivering business ethics course to students attending this institution” (WS). Thus, this respondent’s experience of reportedly unethical behaviour on the part of his employer made it difficult for him to feel at ease in teaching BE to students of the same establishment. This kind of rationality is also demonstrated by BE professors who, having taken a strong stance in the past, feel they have suffered in consequence, and have chosen to withdraw from system (i.e., have decided not to work for that particular business school in the future). Such experiences often result in expressions of disillusionment and/or cynicism.

Four Kinds of Performances Enacted by BE Professors

As explained earlier, most scholars relying on Goffman’s work (see Ringel, 2019; Bullingham & Vasconcelos, 2013; Patriotta & Spedale, 2009), have not distinguished between different kinds of performances. This would inadvertently imply that there are as many performances as there are social interactions, making it virtually impossible to compare across performances. In contrast, we identify four kinds of performances employed by our respondents, namely the ‘onlooker’, the ‘federator’, the ‘crusader’, and the ‘fatalist’, as emerging from the four underlying rationalities discussed in the previous section. Our argument is that when a professor adopts a certain kind of rationality, over time (s)he develops a preference for a corresponding kind of performance. This argument is grounded in the understanding that people seek a consistency between their thoughts (even if subconscious and subjective) and their displayed behaviour.

The first kind of performance is embedded in the self-focused rationality. Here the respondent, when faced with an ethical challenge in class, chooses to stay on the fence and not take a stance offering different academic reasons for doing so. As an example, one professor explains that he chooses to stay on the fence so as to avoid impeaching students’ autonomy in the learning process, “When I teach ethics I try not to get very personally involved because I want to let students explore their own potential and ideas, so I try not to guide them too much” (ME). Other professors choose to stay on the fence because they see their role as facilitating students’ learning as opposed to directing them along specific lines of thinking, “ I stay neutral when it comes to discussions within the class, sometimes the ethical questions will generate quite a dynamic conversation and there I jump into the role of a facilitator… saying “ok, there are 4 people who are saying X but there are 2 people saying Y…” – I try to recognize the weight of something in the class, and the fact that is not right or wrong, …you might find yourself in a different balance with a different group….I also use that as teaching tool” (CN). As is evident, this respondent chooses to focus on weighing different standpoints within the group and on comparing across groups, rather than proferring her own standpoint on the topic. Yet other respondents cite students’ cultural background as a reason for not taking a stance. As one professor reported, “French people voice out their disagreement easily, but there are many nationalities that don’t, especially Chinese students. Therefore, if you give too strongly your ideas and they disagree with it, then they might stay silent, just not participating in the class, or even get offended” (AA). Thus, although these respondents refrain from explicitly sharing their viewpoints, they do not do so because of lack of commitment, but rather because they prioritize optimal student learning. We label such performance as the ‘onlooker’.

The second kind of performance is grounded in the group-focused rationality. Respondents employing such rationality recognize all different standpoints on an ethical issue, including their own. Yet, they do not impose their standpoints on students, nor do they allow one voice to dominate the others. For example, one respondent explains, “I share my viewpoint but then I also share on which systems of values my viewpoint is based. So I share it, but I do not convince others in [sic] it, but just explain why I think in a specific way” (DT). While explaining his viewpoint, this respondent does not aim ‘to convert’ students to his way of thinking. While this performance demonstrates proactivism (I share my viewpoint but then I also share on which systems of values my viewpoint is based), it also shows the ability to maintain a balance of power by not imposing one’s viewpoint on the students (I share it, but I do not convince others). We also found instances of this kind of performance in our field study. For instance, when the topic of the relativism of ethical beliefs and practices came up, some students argued that ethical beliefs are relative to contexts and cultures, others argued that ethical beliefs are universal. As the discussion became more intense, the teacher stepped in not only acknowledging diverse perspectives, but also tracing out the commonalities between them. He concluded that while some ethical beliefs are universal others could vary according to national cultures and contexts. Considering the professor’s practice of allowing for diverse viewpoints to be heard and aiming for a consensus (even if partial) to emerge from the debate, we call such a performance the ‘federator’.

The third kind of performance is grounded in the principle-focused rationality. Professors engaging in such a performance enact their behaviours from a space of unflinching conviction, even if this results in undesirable consequences (for them or for others). When faced with an ethical challenge in class, they not only take a stance, they also impose it on students and expect them to abide by the same. For instance, one respondent shared, “[when]..there is a clash of values between me and the students….I take a stance, I do not make compromises” (PG). Their unequivocal support to a standpoint shows their commitment to it and their willingness to fight for it. Consider the example of one professor, who explicitly took a stand and held his ground when a female student from a conservative background complained against him for his use of certain examples and vocabulary in class. In his words, “Surely, if you go to study management at a postgraduate level in a Western school, then you may see Western material- and is Jarvis Cocker’s intemperate language more upsetting than what Monsanto does to the general public and the environment with ‘Roundup’?” (BD). This quote reveals that not only does the professor have a conviction, he does not hesitate to stick by it and defend it in class. We refer to such a performance as the ‘crusader’.

The fourth and final kind of performance is grounded in the survival or self-protection rationality. We find such performances displayed by professors, who having held strong viewpoints on certain ethical issues in the past, feel censured or can no longer express them because they have either voluntarily withdrawn from the systems or have been forcibly excluded from the system. As one such professor cited at the end of the previous paragraph reported, in the aftermath of the afore-cited incident, “[I] resigned from the school and I refused to work there. I had to refuse to acknowledge the authority of an academic integrity committee that was convened to discuss the use of materials in my ethics course. I had a struggle over doing that. …. If that is the case then we really need to question our ethics in higher education. Some institutions appear to be more concerned with aesthetics and school ratings, rather than the impact of the teaching” (BD). This quote reveals that although earlier on, this professor was acting from a space of unflinching conviction (i.e., the crusader performance), the fact that his choices were questioned by a disciplinary action committee, resulted in a major shift in his performance: from a conviction based one to a more pessimistic and disillusioned one, eventually leading to his withdrawal from said institution. Another professor felt compelled to compromise her voice for fear of reprimand: “For me it is very much a controlled environment- you are told what to do and what not to do- and when that changes, you do not have a choice- even if that compromises you…- when I said something to a colleague- when they found out- even if it is true. I would get punished” (HM). As is evident from this quote, this respondent perceives considerable pressure from her employer to not share her concerns with other employees. We refer to such a performance as the ‘fatalist’. We reckon our respondents do not willingly choose to perform in this way, they are compelled to do so due to the pressure applied on them by the system. We also found evidence of such fatalism bordering on disillusionment and cynicism in a comic strip produced by one respondent (see Fig. 2 below).

Thus, our analysis reveals four kinds of performances embedded in four kinds of underlying rationalities. The onlooker performance is embedded in the self-focused rationality, and professors engaging in this performance are neither expressive of their personal viewpoints, nor do they impose their viewpoints on students. Conversely, those engaging in a federator performance are guided by the group-focused rationality. They are expressive of personal viewpoints but do not impose these on students, treating their own viewpoint as one of many opinions on a complex problem and seeking a consensus (even if partial) among the different viewpoints. Those engaging in a crusader performance are driven by a principled rationality. They are both expressive of their viewpoints as well as impose it on others as being the best (or at least, better) way of addressing a problem. Finally, the fatalist performance is embedded in the self-preservation/survival rationality. Expressivity is curtailed in such cases, and unlike the other three kinds of performances, individuals exhibiting the fatalist performance experience considerable imposition from (rather than exercise imposition on) their environments. Thus, our findings reveal that the four kinds of emerging performances can be delineated along two underlying dimensions surfacing from our data: high versus low degree of expressivity of one’s viewpoint, and imposition of one’s viewpoints on others versus the imposition of other’s viewpoints on oneself.

BE Professors Enacting More Than One Kind of Performance Within an Interaction

Although round 2 of data analysis led us to identifying the four kinds of performances embedded in four kinds of rationalities, the subsequent analysis of the field notes (round 3) resulted in a very interesting insight. We observed that although business professors prefer performances consistent with their initial images, they are also capable of enacting different kinds of performances within the same in-class interaction. As an example, we observed that one professor often encouraged an open dialogue on a variety of topics including the subjective nature of ethical judgments, the viability of profitability and ethical conduct, and many others. During these discussions, students freely expressed their viewpoints, sometimes disagreeing with one another and the teacher. The teacher volunteered his standpoint, while presenting it as one of many viewpoints, and with no obligation for students to agree with him. Thus, he displayed a federator performance, for the most part. However, in a particular instance where students pointedly asked the teacher’s viewpoint on a controversial topic (in this case, Bill Gates’s contribution to climate control), he was reluctant to take a stance, and chose to shift the discussion toward the need for a democratic balance between growth and production. This indicates the teacher relying on the onlooker performance in this particular case. This observation compelled us to reanalyse our interview transcripts to assess whether this finding could be supported through the interview data.

Interestingly, our interview transcripts revealed several examples of respondent shifting from one kind of performance to another during the course of the same in-class interaction. For instance, one respondent demonstrated both the onlooker as well as the federator performances. He stated, “During debates, I stay impartial, and I facilitate the process, making sure that rules of the debate are followed” (PT), clearly demonstrating the neutral stance of the onlooker. However, he also demonstrates his use of the federator performance: “At the end of the class, they ask me what my honest opinion is on the topic, and then I share my opinion, highlighting that this is not necessarily the best opinion or the right opinion….that my opinion does not have any more value than anyone else’s opinion for that matter” (PT). As is evident in this quote, the respondent not only solicits everyone’s opinion, he also shares his own opinion without imposing it on others. While we observed many examples of a teacher shifting between the onlooker and the federator performances, we also found a few examples of transitions from an onlooker to a crusader performance. Consider the following quote from one of our respondents: “When a student asks my opinion, I try to show the positive and negative outcomes of different points of view- I do not clearly stand for one point of view” (AP). The respondent’s preference of maintaining a neutral stance, even when questioned directly by students, is indicative of her performance as an onlooker. Yet, she goes on to add, “Except if it is something that is really wrong- like polluting- they are not allowed to go against the law- no one can be outside the law” (AP). This last statement shows that the same respondent when faced with certain ethical issues, demonstrates the decisive and unequivocal stance of a crusader.

Discussions and Theoretical Contributions

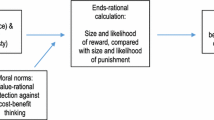

Our paper exposes four underlying rationalities leading to the emergence of four corresponding types of performances displayed by BE professors in the classroom. As such, its first contribution is to the body of literature relying on Goffman’s notion of performances. Although Goffman (1959) himself had hinted at different kinds of performances, he did not build on this line of thinking, nor did he propose what could have been a comprehensive framework of different kinds of performances. Most subsequent literature relying on Goffman’s work (see Ringel, 2019; Bullingham & Vasconcelos, 2013; Patriotta & Spedale, 2009), also conceptualized performances as a unidimensional and simplistic concept, indirectly implying that there could be almost as many kinds of performances as there are people and social interactions, thereby rendering comparisons across performances nearly impossible. In contrast, we show that there are four kinds of performances emerging from different levels of two underlying dimensions: (1) professors’ degree of expressiveness of their viewpoints on a subject being discussed in class, and (2) the degree to which they impose their viewpoints on students or the degree to which they experience imposition from other dominant players in their environments. Plotting high and low levels of these two dimensions against one another would result in the four distinct types of performances: (1) on the bottom left-hand quadrant is the onlooker, a performance that is low both on expressiveness and on imposing viewpoints on others, (2) on the bottom right-hand quadrant is the federator performance characterized by high degree of (collective) expressiveness but a low preference for any one viewpoint dominating the others, (3) diagonally opposite to the onlooker and in the top right-hand quadrant is the crusader performance, which is high on expressiveness as well as on imposing one’s viewpoints on others, and (4) on the top left-hand corner is the fatalist performance, characterised by professors demonstrating low degree of expressiveness of their own viewpoints (for fear of backlash) and experiencing high degree of imposition from other dominant players in their environment. Thus, by grounding our reflections in two basic dimensions emerging from our data set (namely, degree of expressivity and degree of imposition), we offer a comprehensive framework of four kinds of performances (see Fig. 3 below). Plotting high and low levels of the two underlying dimensions against one another, results in four kinds of emergent performances, each of which has been elaborated in our framework.

Our framework offers partial support to Macfarlane et al. (2004) conceptual paper, wherein they present three possible reactions from BE professors to the ethical challenges they face in class: (1) an objective and neutral stance allowing students to develop their own perspectives without the teacher’s influence (2) a non-neutral standpoint guided by the understanding that autonomy of learning does not mean that students are free to hold just any belief they desire, and (3) a flexible standpoint whereby the levels of restraint applied by the BE professor are fluid and contingent on circumstances. We find empirical support for the neutral stance in what we label the onlooker performance, for the non-neutral position in what we call the crusader performance, and partially for the flexible standpoint in the federator performance. However, we also go one step further and identify a fourth kind of performance, namely the fatalist. Further, we also point out that our four emergent performances are not rigid categories or typologies of performances; rather they represent professors’ shifting preferences regarding how they deal with complex experiences within the evolving contexts of their classes. While underlying rationalities influence professors’ preferred performances, once the performance is established, professors also employ the relevant rationality to justify their choice of performance. Thus, rationality and performance co-exist in a mutually reinforcing relationship. Nevertheless, when a professor chooses to shift from one performance to another during the course of an interaction, this also suggests a shift from one underlying rationality to another. Table 2 below outlines the four performances, their underlying rationalities, their characteristics, and a few illustrative quotes.

Our extrapolation of the four different kinds of performances also addresses one of the earlier criticisms of Goffman’s work: that it supposedly fails to consider the influence of power and social structure on shaping individuals’ attitudes and actions (Gouldner, 1970). Our exposition of the four performances shows not only to what extent BE professors express themselves, but also how much they ‘impose’ their viewpoint on their students or experience imposition from other dominant players in the system. In other words, we expose how much of power/influence BE professors exercise on their students or alternatively, in some cases, how much power is exercised on them by others. While those engaging in an onlooker or federator performance choose not to impose their viewpoints (i.e., exercise power) on their students, crusaders not only impose but also to expect to convert students to their viewpoints. Thus, while the former two kinds of performances are more egalitarian, the third is not so. In contrast, those engaging in the fatalist performance are explicitly excluded from expressing their opinions, and are subjected to censorship by those who are more powerful in the organization. As such, of the four kinds of performances, those engaging in the fatalist performance experience more imposition by dominant players in the system. Thus, not only does our framework address past criticisms of Goffman’s work being ignorant of power, it also exposes how power plays out in social interactions within the classroom. As such, we offer support to Leib’s (2022) recent work on the micro-physics of power in Goffman’s work.

Our work also contributes to sensemaking literature by complementing and extending previous studies on ethical sensemaking. Maclagan (2003) highlighted self-interest as foundational to ethical challenges where the outcome depended on individual motivation. In our case, the onlookers’ attempts to preserve their values drive their choice for self-interest. In support of a collective interest focus (cf. our federator performance), Jacobs and Keegan (2018) debunked the ‘me’ focus in change literature highlighting care for colleagues as paramount for workers undergoing a morally laden change effort. We also find similarities between our federator performance and Reinecke and Ansari’s (2015) notion of ‘ethical truce’, whereby multiple parties seek to reach an acceptable agreement, which might not entail perfect consensus. Our findings present a nuanced view of collective care through efforts of giving voice as opposed to care ethics (Valentine et al., 2010). The performance of the crusader displays what has been referred to as ethical blindness (Palazzo et al., 2012) whereby their imposition of viewpoints on others does not arise from a harmful orientation but rather from a high sense of conviction. These studies all point to specific aspects of our 2 × 2 matrix with no study combining all four as we do. Our approach has the theoretical advantage of presenting a comprehensive understanding of alternative sensemaking routes from a complex setting leveraging human agency. In so doing, we also respond to recent calls to focus on the sensemaking processes rather than on its outcome (Schildt et al., 2020). Further, our focus on day-to-day interactions enriches the crucial yet relatively underdeveloped literature on the interactive and relational aspects of sensemaking (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014).

Also, in Weick’s framework, sensemaking originates from the human need to cope with situations of ambiguity typically triggered by disruptive occurrences, such as interruptions, surprises, crises, and breakdowns. However, through the use of Goffman’s framework, our study shows that simply the co-presence of different viewpoints between the BE teacher and the students is an occasion for sensemaking, because such a co-presence prompts controversies over face and meaning that need to be reconciled through face work aimed at coping with the situation. Thus, we support Patriotta and Spedale’s (2009) observation that the ambiguity which instigates sensemaking may not emerge always due to exogenously imposed disruptions or surprises. Rather it can also emerge endogenously through co-presence of different faces in a social interaction. Indirectly, we lend support to scholars who have recommended approaching sensemaking as a ‘continuous’ or ‘ongoing’ process (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Reinecke & Ansari, 2015; Weick, 2012) occurring as part of mundane daily interactions, rather than solely as a study of distinct episodes triggered by particular disruptive events (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015). By paying attention to the “emerging demands, dilemmas, and ambiguities of presently evolving situations”, we contribute to present-oriented sensemaking as our professors “engage in the iterative exercise of contextualizing judgment and continually adjusting it to the exigencies of lived situations” (Reinecke & Ansari, 2015, p. 886). In so doing, we contribute to Reinecke and Ansari’s (2015) call to provide a deeper understanding of the present-oriented dimension of sensemaking.

Practical Implications

Our present work provides practical implications to business schools, especially those in Western countries, by exposing that teaching ethics is a far more complicated exercise than has been previously understood. Consequently, we call for an open dialogue amongst BE teachers within and across business schools on the topic. Such an exercise could be facilitated by organizations such as the EBEN. This will enable creation of awareness, sharing of best practices, and learning from one another. Ignoring these complexities could result in many well-intentioned and qualified professors feeling ill-equipped, unsupported, and eventually disillusioned and disengaged from teaching BE. This sentiment, if unchecked, could undermine decades of accrued gains from teaching BE to sensitize future managers toward their ethical responsibilities.

We also offer practical recommendations to BE professors. While BE professors have their innate preferences for one or more kind of performances, they need to be conscious of the fact that each kind of performance has its pitfalls when taken to an extreme. For instance, while a professor performing as an onlooker might give students the space to develop their autonomous thinking on an ethical issue, some students might perceive such a stance as the professor’s disinterest or lack of commitment. In contrast, while the crusader performance could be seen as being committed to a standpoint, it may, when taken to an extreme, be perceived as being exceedingly authoritarian, engendering resistance or even hostility among students. Although the federator performance facilitates the emergence of a collective voice, it may be seen as consensus-seeking while relying on popular opinion and avoiding an explicit stance on a controversial topic. And, finally, although the fatalist is a passive performance, if observed too frequently, it is symptomatic of a larger underlying problem in the system. Since each kind of performance has its pitfalls when taken to an extreme, not recognizing these could result in less-than-optimal outcomes for both students and professors. Students would not cultivate the conviction to challenge unethical practices if they perceive their teachers as skirting ethical issues, or being either too uncompromising or too compliant. Therefore, an awareness of how their performances are being perceived and how these influence students’ emerging standpoints toward ethical issues will be very helpful for professors to fine-tune their performances.

Additionally, performances influence impressions created on audiences, and these in turn influence outcomes. When performances are considered competent, credible and believable, they have the potential to influence organizational level outcomes (Mueller, 2018) like fostering strategic change (Whittle et al., 2021) and enhancing organizational credibility (Khoury et al., 2022). Applying this to our study, we reckon that professors’ performances will also influence the extent to which the aim of sensitizing business students to future ethical challenges will be achieved. Therefore, professors need to be conscious not only of their preferred performance but also how this impacts student learning outcomes. Additionally, professors may need to resort to performances other than their preferred ones, to effectively handle in-class interactions. For instance, if they find students presenting arguments grounded in a misguided belief system, then irrespective of their innate preferences, professors might need to resort to the crusader performance, challenging students’ line of thinking. Conversely, if they find students feeling lost due to the plurality of viewpoints presented in class, then irrespective of their innate preferences, professors might need to rely on the federator performance to facilitate an emerging consensus and consequently, student learning. In contrast, if they find that students are not expressing themselves due to cultural or other reasons, then adopting an onlooker stance might be best suited, thereby giving students the space to express themselves. Finally, the fatalist performance does little to enable student learning, and should therefore be discouraged. We conclude that if the purpose of sensitizing students toward future ethical challenges is to be effectively achieved, then professors may need to strategically choose the kind of performance that best fits with the classroom context, and adapt their performances accordingly. We do not mean to suggest that shifting from one’s innate preferences to the kind of performance that best fits with the in-class context is, by any means, an easy exercise. However, doing so may be required for students’ optimal learning outcomes. Therefore, raising awareness among BE professors of the kind of performances they inherently prefer versus the kind of performances they need to display when faced with different in-class contexts might be a worthwhile exercise.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Our work has scope for future development, both conceptually as well as methodologically. As a first point, our focus in the present paper is limited to the performance of BE professors; it does not take into consideration the performance enacted by the students, which may also influence and be influenced by the professor’s performance. A more complete understanding of the phenomenon would require a two-way investigation of the ongoing and mutually influencing performances of both professors and students. Similarly, studies can also be conducted to explore how professors’ performances in BE classes evolve as a result of their ongoing interactions with other BE professors over time. Next, since our present work stops short at identifying different kinds of performances, future studies could empirically explore how each of these performances influences different aspects of student learning. Finally, in future research, the performances of both teachers and students can be plotted to see how ethical truces (cf. Reinecke & Ansari, 2015) might emerge [or not] on sensitive/controversial topics from the ongoing interactions between these varied performances.

Our work also presents certain methodological concerns. Since during our interviews we asked our respondents to retrospectively narrate their in-class experiences, there is a possibility that their responses were tainted by the social desirability bias. Indeed, in qualitative research, the researcher and the researched influence and are influenced by one another (Amis & Silk, 2008). Nevertheless, we have minimized this bias by triangulating interview-based data with our observations of BE professors in class. Next, although our respondents represent many different countries of origin and have considerable international teaching experience, one could point out that most respondents are from the Western world, and therefore our findings are Western-centric. Therefore, we call for future empirical explorations of the topic across different countries and settings. Further studies can also be conducted to assess whether the performances displayed by permanent faculty of BE would vary in any way from those displayed by visiting/adjunct faculty, or whether variations might be observed between full-time and part-time BE faculty.

Conclusions

Business ethics professors bear the heavy responsibility of sensitizing future managers regarding the ethical challenges they might face at work, a need that has never been more marked than it is in today’s business environment replete with ethical scandals. Yet, these professors themselves face a variety of ethical challenges while teaching BE. Professors rely on different rationalities to make sense of these challenges, which then result in them enacting different kinds of performances, sometimes shifting from one performance to another within the space of the same in-class interaction. Our paper sheds light on these interactions between BE professors and students, and exposes some of the inherent tensions as professors try to influence the patterns of interaction in the classrooms while simultaneously maintaining a coherent image of the self. By exposing the unique complexity characterizing in-class interactions in BE classes, we hope to initiate a dialogue among BE professors across countries, so that they may find a platform for expression and support in fulfilling their roles. We also emphasize the need for professors to adapt their performances to best fit with specific in-class contexts, while concurrently being mindful of the pitfalls of taking any performance to the extreme. The reflections presented in this paper not only call attention to the unique challenges of teaching BE, they also offer some insight into how these challenges may be addressed, so as to maintain and reinforce BE professors’ commitment to this field.

Notes

It could be argued that professors teaching other subjects, such as history, for example, may also find that some of the topics they evoke in class are upsetting to students. Having said this, the challenge is amplified when ethics is the main content of the module, as is the case with BE courses.

While an individual may stop processing information without being conscious, rejecting information involves making a conscious choice to disregard information challenging the individual’s existing worldview. Nevertheless, both exercises remain subjective in nature.

In France, the status of ‘professeur agrégé’ is obtained once a competitive examination (called “agrégation”) for civil service in the public education system is passed. To qualify, candidates need to hold at least a five-year university diploma (Master’s degree).

Observation sessions were conducted for 3 hours on 11/10/2022, and 7 hours each on 24/10/2022 and 25/10/2022.

The students were explicitly asked if they were comfortable with the second author’s presence in the classroom. The students not only consented, they also came over to her during the break to ask about the topic of her research, to which she responded briefly and honestly.

References

Amis, J. M., & Silk, M. L. (2008). The philosophy and politics of quality in qualitative organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 11(3), 456–480.

Balogun, J., Bartunek, J. M., & Do, B. (2015). Senior managers’ sensemaking and responses to strategic change. Organization Science, 26(4), 960–979.

Beames, S. K., & Pike, E. C. (2008). Goffman goes rock climbing: Using creative fiction to explore the presentation of self in outdoor education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 12(2), 3–11.

Birnbaum, M. G. (2008). Taking Goffman on a tour of Facebook: College students and the presentation of self in a mediated digital environment. The University of Arizona.

Blumer, H. (1954). What is wrong with social theory? American Sociological Review, 19(1), 3–10.

Boje, D. M., Rosile, G. A., Saylors, J., & Saylors, R. (2015). Using storytelling theatrics for leadership training. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 17(3), 348–362.

Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 12–23.

Brown, A. D., Colville, I., & Pye, A. (2015). Making sense of sensemaking in organization studies. Organization Studies, 36(2), 265–277.

Brown, R., Waring, R., & Donkaewbua, S. (2008). Incidental vocabulary acquisition from reading, reading-while-listening, and listening to stories. Reading in a Foreign Language, 20, 136–163.

Bullingham, L., & Vasconcelos, A. C. (2013). ‘The presentation of self in the online world’: Goffman and the study of online identities. Journal of Information Science, 39(1), 101–112.

Christensen, L. J., Peirce, E., Hartman, L. P., Hoffman, W. M., & Carrier, J. (2007). Ethics, CSR, and sustainability education in the Financial Times top 50 global business schools: Baseline data and future research directions. Journal of Business Ethics, 73(4), 347–368.

Clark, J. (2004). The ethics of teaching and the teaching of ethics. New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work, 1(2), 80–84.

Collins, D., Weber, J., & Zambrano, R. (2014). Teaching business ethics online: Perspectives on course design, delivery, student engagement, and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(3), 513–529.

Cornelius, N., Wallace, J., & Tassabehji, R. (2007). An analysis of corporate social responsibility, corporate identity and ethics teaching in business schools. Journal of Business Ethics, 76(1), 117–135.

Czarniawska, B. (2006). A golden braid: Allport, Goffman, Weick. Organization Studies, 27(11), 1661–1674.

De George, R. T. (2010). Business ethics (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Douglas, M. (1970). Natural symbol: Explorations in cosmology. Barrie and Rockliff.

Feldman, M. S., & Orlikowski, W. J. (2011). Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization Science, 22(5), 1240–1253.

Fitz-Gibbon, C. T., Taylor, F. G. C., Morris, L. L., & Lyons, M. L. (1987). How to analyze data (No. 8). Sage.

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (pp. 3–30). Basic Books.

Goffman, E. (1956). The nature of deference and demeanour. American Anthropologist, 58(3), 473–502.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. Anchor Books.

Gouldner, A. (1970). Other symptoms of the crisis: Goffman’s dramaturgy and other new theories. In The coming crisis of western sociology (pp. 378–390).

Hales, S., Riach, K., & Tyler, M. (2021). Close encounters: Intimate service interactions in lap dancing work as a nexus of ‘self-others-things.’ Organization Studies, 42(4), 555–574.

Hancock, B. (1998). Trent focus for research and development in primary health care: An introduction to qualitative research. Trent Focus, 27.

Harley, D., & Hunn, V. (2015). Utilization of photovoice to explore hope and spirituality among low-income African American adolescents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32, 3–15.

Hogan, B. (2010). The presentation of self in the age of social media: Distinguishing performances and exhibitions online. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 30(6), 377–386.

Jacobs, G., & Keegan, A. (2018). Ethical considerations and change recipients’ reactions: ‘It’s not all about me.’ Journal of Business Ethics, 152, 73–90.

Jacobsen, M. H., & Kristiansen, S. (2014). The social thought of Erving Goffman. Sage Publications.

Khan, S. (2020). Erving Goffman, the presentation of self in everyday life (1959). Public Culture, 32(2), 397–404.

Khoury, T. A., Shymko, Y., & Vermeire, J. (2022). Simulating the cause: How grassroots organizations advance their credibility through the dramaturgical curation of events. Organization Science, 33(4), 1470–1500.